Published online Jan 27, 2022. doi: 10.4254/wjh.v14.i1.287

Peer-review started: October 8, 2021

First decision: November 17, 2021

Revised: November 23, 2021

Accepted: December 31, 2021

Article in press: December 31, 2021

Published online: January 27, 2022

The liver has traditionally been regarded as resistant to antibody-mediated rejection (AMR). AMR in liver transplants is a field in its infancy compared to kidney and lung transplants. In our case we present a patient with alpha-1-antitrypsin disease who underwent ABO compatible liver transplant complicated by acute liver failure (ALF) with evidence of antibody mediated rejection on allograft biopsy and elevated serum donor-specific antibodies (DSA). This case highlights the need for further investigations and heightened awareness for timely diagnosis.

A 56 year-old woman with alpha-1-antitrypsin disease underwent ABO compatible liver transplant from a deceased donor. The recipient MELD at the time of transplant was 28. The flow cytometric crossmatches were noted to be positive for T and B lymphocytes. The patient had an uneventful recovery postoperatively. Starting on postoperative day 5 the patient developed fevers, elevated liver function tests, distributive shock, renal failure, and hepatic encephalopathy. She went into ALF with evidence of antibody mediated rejection with portal inflammation, bile duct injury, endothelitis, and extensive centrizonal necrosis, and C4d staining on allograft biopsy and elevated DSA. Despite various interventions including plasmapheresis and immunomodulating therapy, she continued to deteriorate. She was relisted and successfully underwent liver retransplantation.

This very rare case highlights AMR as the cause of ALF following liver transplant requiring retransplantation.

Core Tip: The liver has traditionally been regarded as resistant to antibody-mediated rejection (AMR). AMR in liver transplants is a field in its infancy compared to kidney and lung transplants. We present a case of a 56 year-old woman with alpha-1-antitrypsin disease who underwent ABO compatible liver transplant. The flow cytometric crossmatches were noted to be positive for T and B lymphocytes. After initial posttransplant recovery she progressively developed acute liver failure with evidence of antibody mediated rejection with portal inflammation, bile duct injury, endothelitis, and extensive centrizonal necrosis, and C4d staining on allograft biopsy and elevated donor-specific antibodies. Despite various interventions including plasmapheresis and immunomodulating therapy, she required retranpslantation.

- Citation: Robinson TJ, Hendele JB, Gimferrer I, Leca N, Biggins SW, Reyes JD, Sibulesky L. Acute liver failure secondary to acute antibody mediated rejection after compatible liver transplant: A case report. World J Hepatol 2022; 14(1): 287-294

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5182/full/v14/i1/287.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4254/wjh.v14.i1.287

Acute antibody mediated rejection after liver transplantation is a rare phenomenon. antibody-mediated rejection (AMR) is a well-known phenomenon in ABO incompatible liver transplantation, and there is a growing body of literature demonstrating the presence of rejection in ABO compatible, crossmatch positive liver transplantation. Medical treatments including plasmapheresis and immune modulating medications have been successful in halting rejection[1]. Here we present a case of acute AMR after ABO compatible, crossmatch positive liver transplantation resulting in acute liver failure (ALF) and rapid clinical deterioration requiring re-transplantation.

A 56-year-old woman with a history of decompensated cirrhosis secondary to alpha-1-antitrypsin deficiency (ZZ phenotype) presented for liver transplantation.

The patient developed refractory ascites requiring repeated large-volume paracentesis and spontaneous bacterial peritonitis.

The patient’s past medical history was remarkable for systemic lupus erythematosus mostly manifesting with arthralgia, hair loss, multiple miscarriages, and one successful pregnancy.

The patient’s temperature was 36.5 °C, heart rate was 60 bpm, respiratory rate was 14 breath/min, blood pressure was 100/60 mmHg and oxygen saturation on room air was 100%. Her abdomen was distended with ascites. She was not encephalopathic.

Laboratory values were sodium 125 meq/L, creatinine 0.95 mg/dL, aspartate aminotransferase (AST) 96 U/L, alanine aminotransferase (ALT) 59 U/L, alkaline phosphatase 263 IU/L, total bilirubin 6.1 mg /dL, albumin 2.6 g/dL, international normalized ratio (INR) 1.8, platelets 60 103/mL.

A computed tomography (CT) of the abdomen and pelvis demonstrated cirrhosis and multiple varices in the abdomen. There was no evidence of malignant liver lesions. Vasculature was patent. There was moderate ascites.

The patient was diagnosed with decompensated cirrhosis with the MELD NA score of 28.

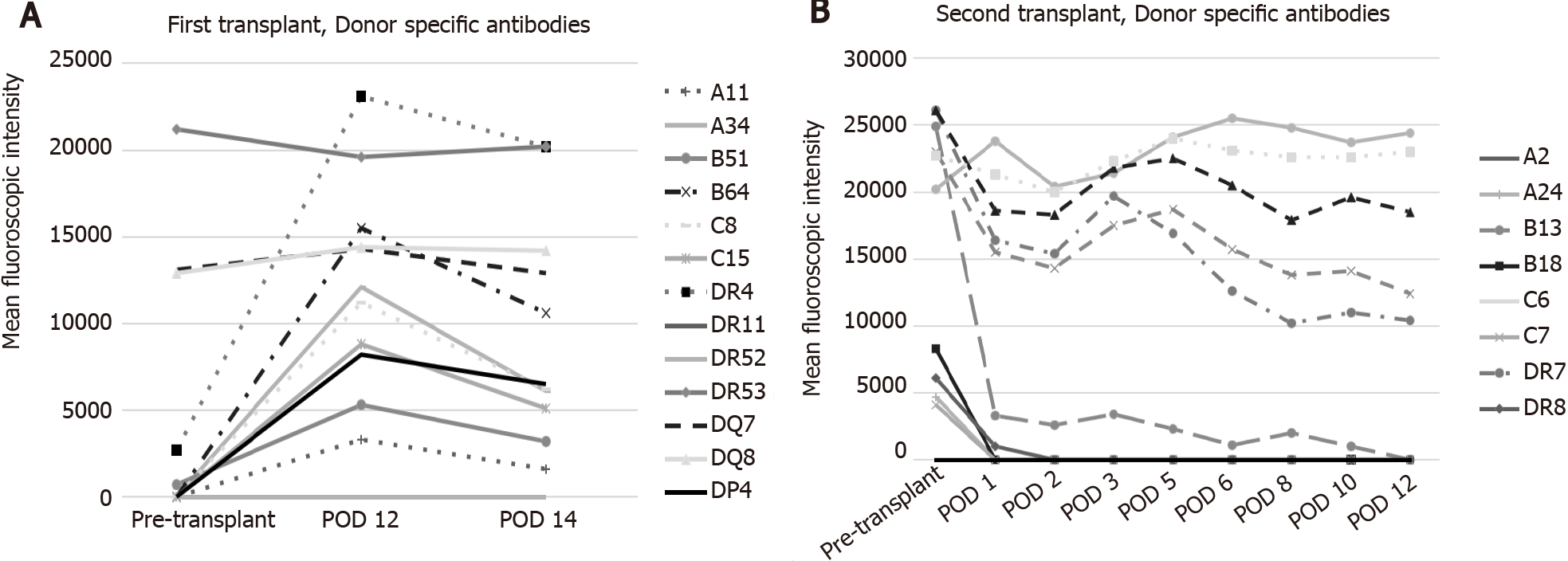

The patient underwent orthotopic liver transplantation from a 55-year-old deceased female donor (cause of brain death was an intracranial hemorrhage). Both recipient and donor were blood type A. Serologic studies revealed the recipient was cytomegalovirus (CMV), Epstein-Barr virus (EBV), and hepatitis C and B negative. Similar testing on the donor revealed CMV seronegativity and EBV seropositivity. The flow cytometric crossmatches were noted to be positive for T and B lymphocytes with the median channel shift (MCS) of 11 and 96, respectively. At transplant, donor-specific antibodie (DSA) against human leukocyte antigen (HLA) Class 1 were B51 at 700 mean fluorescent intensity (MFI), and HLA Class 2 DR04 at 2700 MFI, DR53 at 21,200 MFI, DQ07 at 13, 100 MFI, DQ08 at 12, 900 MFI (Figure 1A and Table 1).

| A11 | A34 | B51 | B64 | C8 | C15 | DR4 | DR11 | DR52 | DR53 | DQ7 | DQ8 | DP4 | |

| Pre-transplant | 0 | 0 | 700 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2700 | 0 | 0 | 21200 | 13100 | 12900 | 0 |

| POD 12 | 3300 | 12100 | 5300 | 15500 | 11200 | 8800 | 23100 | 0 | 0 | 19600 | 14300 | 14400 | 8200 |

| POD 14 | 1600 | 6100 | 3200 | 10600 | 6200 | 5100 | 20200 | 0 | 0 | 20200 | 12900 | 14200 | 6500 |

| C1q | A11 | A34 | B51 | B64 | C8 | C15 | DR4 | DR11 | DR52 | DR53 | DQ7 | DQ8 | DP4 |

| Pre-transplant | Neg | Neg | Neg | Neg | Neg | Neg | Neg | Neg | Neg | 40300 | Neg | Neg | Neg |

| POD 14 | Neg | Neg | 400 | 9700 | Neg | Neg | 17800 | Neg | Neg | 41800 | 42300 | 42540 | Neg |

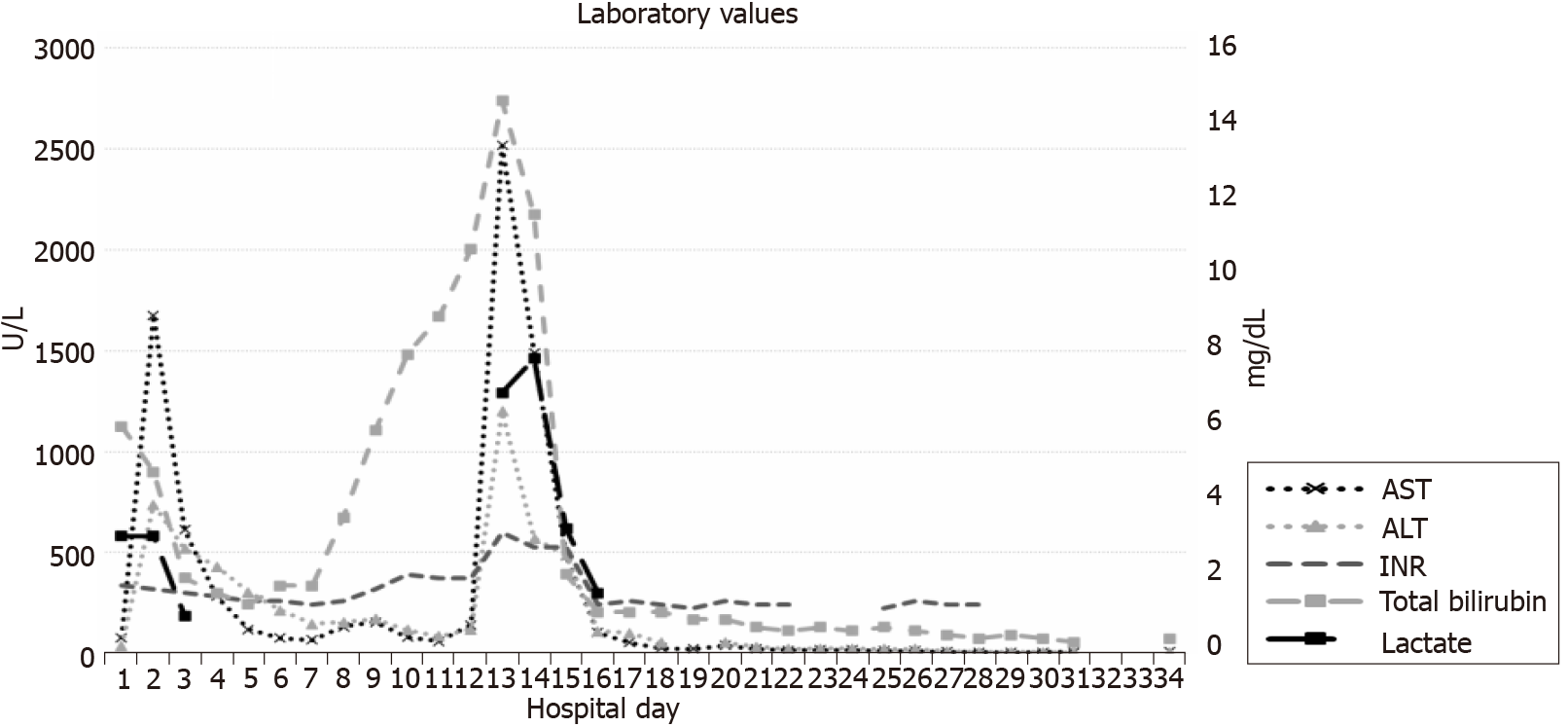

The transplant operation was 5 h. Blood loss was 1500 cc. Intraoperative transfusions were: 6 units of packed red cells, 6 units of FFP, 2 units of cryoprecipitate, and one unit of platelets. The patient had an uneventful recovery postoperatively in the intensive care unit (ICU). She was extubated on POD 0 and was transferred from ICU to an acute surgery care unit on POD 1. Per our protocol her immunosuppression regiment included an induction course of antithymocyte globulin (ATG, 1.5 mg/kg × 3 d) with methylprednisolone taper (1 gm intraoperatively, followed by 500 mg, 250 mg, and 125 mg). This was followed by a maintenance immunosuppression with tacrolimus twice daily monotherapy starting on POD 4 with the goal trough level of 8-10 ng/mL. She achieved a tacrolimus trough level of 11.5 ng/mL on POD 7. Antimicrobial prophylaxis included trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, valgancyclovir, and fluconazole. An immediate postoperative Doppler liver ultrasound (US) and a routine POD 4 US demonstrated patent vasculature with adequate flow with normal velocities. Lactate normalized to 1 on POD 1. On POD 5 AST was 119 U/L, ALT 305 U/L, alkaline phosphatase 79 U/L, and total bilirubin 1.3 mg /dL, INR 1.4 (Figure 2). On POD 5 the patient developed a fever to 40.5 °C and was started on empiric antibiotic therapy with intravenous vancomycin and piperacillin-tazobactam.

A CT of the abdomen and pelvis was performed on POD 7 which did not demonstrate any evidence of intraabdominal abscess or other pathology. An US of the allograft was performed on POD 8 which was again unremarkable.

Between POD 8 and 10 the patient began experiencing intermittent episodes of hypotension. Echocardiography demonstrated a left ventricular ejection fraction of 66% and pulmonary arterial hypertension with pressure of 45 mmHg. The patient developed acute kidney injury with a creatinine of 1.8 mg/dL in a setting of a supratherapeutic tacrolimus levels close to 12 ng/mL. Mycophenolate mofetil was added to her immunosuppression maintenance regimen for renal sparing with the goal to decrease the target tacrolimus trough level of 5 ng/mL.

She worsened acutely clinically with persistent hypotension, volume overload, and grade 2 encephalopathy on POD 11 and was transferred to the ICU. Allograft US demonstrated new low bidirectional flow in left, right, and main portal veins, making it difficult to exclude portal vein thrombosis, but CT scan with contrast confirmed patent portal and hepatic artery inflow. DSAs were rechecked and were noted to be even more elevated (Figure 1), and the patient underwent plasmapheresis on POD 12. A biopsy of the liver was also performed which demonstrated portal inflammation, bile duct injury, endothelitis, and extensive centrizonal necrosis (> 40%) with positive stain for C4d, consistent with acute AMR. This would score as C4d: “3.” and the h-score of “2.” based on the Banff Working Group scoring criteria. On POD 13 she became oliguric and hemodialysis was initiated.

She underwent plasmapheresis followed by a dose of eculizumab as well as ATG. Given her rapid decompensation, multiorgan failure, and evidence of ALF (INR > 1.5, altered mental status, < 26 wk from onset)[2] she was listed for repeat liver transplant. Sample from POD 14 was retrospectively tested for C1q binding and was strongly positive for class I and class II DSA.

A liver became available and she underwent a second orthotopic liver trans

| A2 | A24 | B13 | B18 | C6 | C7 | DR7 | DR8 | DR53 | DQ2 | DQ4 | DP3 | DP4 | |

| Pre-transplant | 0 | 4700 | 24900 | 8300 | 0 | 4100 | 26100 | 6100 | 20200 | 23000 | 26100 | 22700 | 0 |

| POD 1 | 0 | 0 | 3300 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 16400 | 1000 | 23800 | 15500 | 18600 | 21300 | 0 |

| POD 2 | 0 | 0 | 2600 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 15400 | 0 | 20400 | 14300 | 18300 | 20000 | 0 |

| POD 3 | 0 | 0 | 3400 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 19700 | 0 | 21400 | 17500 | 21800 | 22300 | 0 |

| POD 5 | 0 | 0 | 2300 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 16900 | 0 | 24100 | 18700 | 22500 | 24000 | 0 |

| POD 6 | 0 | 0 | 1100 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 12600 | 0 | 25500 | 15700 | 20500 | 23100 | 0 |

| POD 8 | 0 | 0 | 2000 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 10200 | 0 | 24800 | 13800 | 17900 | 22600 | 0 |

| POD 10 | 0 | 0 | 1000 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 11000 | 0 | 23700 | 14100 | 19600 | 22600 | 0 |

| POD 12 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 10400 | 0 | 24400 | 12400 | 18500 | 23000 | 0 |

| C1q | A2 | A24 | B13 | B18 | C6 | C7 | DR7 | DR8 | DR53 | DQ2 | DQ4 | DP3 | DP4 |

| Pre-tx | Neg | Neg | 5200 | 3500 | Neg | Neg | 36300 | Neg | 40800 | 35400 | 36500 | 39200 | Neg |

She underwent induction with ATG and methylprednisolone. Her maintenance immunosuppression included tacrolimus and mycophenolate mofetil. She was treated with plasmapheresis and intravenous immune globulin G (IVIG) in the immediate post-operative period as well as rituximab (POD 3 and 19 after second transplant). Liver biopsy on POD 8 demonstrated mild endothelitis, prompting additional treatment with IVIG and plasmapheresis as well as bortezomib (POD 7 and 9 after her second transplant).

Her post-transplant course was complicated by vancomycin resistant enterococcal infection of the wound and ascites that was adequately treated with daptomycin. Immune globulin G (IgG) against donor class I HLA were quickly reduced after the second liver transplant (POD 1) but class II HLA antibodies remained high in post- transplant monitoring.

The patient recovered well from the second transplant and was discharged home on hospital day 30. Her maintenance immunosuppression consisted of tacrolimus, rapamycin, and prednisone. She is currently over 2 years after transplant with normal liver transplant and native kidney function, still with DSA class II being positive at moderate levels with DR53 at 5100.

The liver has traditionally been regarded as resistant to AMR. Various reasons for this have been postulated, including dual blood supply, large vascular bed resulting in a diluted effect of circulating DSA, and secretion by kuppfer cells of HLA that neutralize DSA[3]. Rejection after liver transplantation could be cellular, humoral or mixed[1]. Rejection can be sub-classified according to the timing of onset. There are three types of AMR: Hyperacute, acute, or chronic[4]. In particular, acute AMR in the setting of ABO-compatible liver transplantation is an exceedingly rare phenomenon and the true incidence is unknown. A large French series of 1788 liver transplant patients reported an acute AMR rate of 0.56%[5]. Another smaller study reported up to a 3.6% rate of AMR[6]. Although there is an increasing body of literature on the topic, most of this is in the form of case reports. While there are assays performed prior to transplantation that can provide information about preformed antibodies, cytotoxic potential of these antibodies, as well as the presence of reactive T- and B-lymphocytes, the clinical significance of alloantibody is not fully understood[7]. At present testing pre-transplant for preformed DSA is not a standard practice for all liver transplant centers. Both HLA and non-HLA antibodies can cause rejection, but it is important to note that not all HLA antibodies are pathogenic[8]. Class I HLA with or without class II HLA are associated with acute AMR while class II HLA, specifically HLA-DQ, are associated with worse outcomes in chronic rejection[9]. DSA and resulting complement fixation have been found to be markers for AMR, both acute and chronic[10-12]. Risk factors for DSA development as well as the detrimental effects on the allograft have been identified, including higher MELD score, re-transplantation, use of cyclosporine, lower immunosuppression, variability in the level of tacrolimus, and non-adherence to immunosuppression therapies, female donor, and recipient/donor gender mismatch[9]. In 2016, the Banff Working Group published diagnostic criteria for acute AMR which include histopathologic pattern of injury consistent with acute AMR, positive serum DSA, diffuse microvascular deposition of C4d, and reasonable attempts made to exclude other causes of allograft failure[13]. Recently Halle-Smith et al[14] described two cases of AMR presenting with graft dysfunction and being associate with lactic acidosis, hypoglycemia, and eosinophilia in both blood and liver biopsies[14]. Baliellas et al[15] described AMR manifesting as a sinusoidal obstruction syndrome with the patient presenting with pleural effusion, ascites found to have venulitis and diffuse C4d staining in the central veins on liver biopsy[15]. Vascular thromboses both venous and arterial in a setting of elevated DSAs presumably related to AMR have also been described in the literature[16,17]. All these criteria will hopefully lead to increased diagnostic sensitivity which will in turn lead to greater understanding of the true incidence and risk factors, improved treatment options, and potentially changes in practice in crossmatch positive liver transplantation.

Treatment of acute AMR has been described mostly in case reports and is of variable efficacy. Regimens have been based on advances made in ABO incompatible liver transplantation and include plasmapheresis, intravenous immune globulin, rituximab, and basiliximab[18]. Case reports have demonstrated successful rescue from AMR with the use of regimens of mycophenolate mofetil and plasmapheresis, IVIG, corticosteroids, ATG, rituximab, bortezomib, or a combination of the above[19-22].

Our sensitized female patient with pre transplant DSAs developed ALF a week after successful deceased donor liver transplant in a setting of robust immunosuppression exhibiting graft dysfunction, hepatic encephalopathy, rising lactate, and renal failure requiring dialysis with definitive evidence of AMR. She was treated with salvage eculizumab, plasmapheresis, and IVIG. Her graft biopsy was impressive for over 40% hepatocyte necrosis with C4d staining without evidence of eosinophilia. As a result of minimal improvement despite aggressive therapy, the decision was made to pursue re-transplantation. Her explant allograft biopsy confirmed similar findings. After her second liver transplant, she underwent induction with ATG and methylprednisolone and was kept on tacrolimus and mycophenolate mofetil. After induction was complete, DSA levels were followed (Figure 1B and Table 1) and plasmapheresis and IVIG therapy was instituted along with rituximab and bortezomib. Even though she has normal liver function tests, because of the presence of HLA class II Ab, future liver biopsies are contemplated.

In conclusion, we believe our case is one of the rare cases in the literature that describes AMR resulting in ALF treated with re-transplantation. We hypothesize that even though the DSA levels were higher after the second liver transplant, the class I Ab became negative immediately after the second transplant, while class I Ab associated with C1q positivity dramatically increased after the first liver transplant leading to irreversible liver injury requiring re-transplantation. We advocate for closer monitoring of DSA post liver transplantation to further elucidate their effect on liver transplant outcomes.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country/Territory of origin: United States

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Inoue K, Wang J S-Editor: Fan JR L-Editor: A P-Editor: Fan JR

| 1. | Choudhary NS, Saigal S, Bansal RK, Saraf N, Gautam D, Soin AS. Acute and Chronic Rejection After Liver Transplantation: What A Clinician Needs to Know. J Clin Exp Hepatol. 2017;7:358-366. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 64] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 84] [Article Influence: 12.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Bernal W, Wendon J. Acute liver failure. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:2525-2534. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 736] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 747] [Article Influence: 67.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 3. | Colvin RB. C4d in liver allografts: a sign of antibody-mediated rejection? Am J Transplant. 2006;6:447-448. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 23] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Lee M. Antibody-Mediated Rejection After Liver Transplant. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2017;46:297-309. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 20] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Del Bello A, Neau-Cransac M, Lavayssiere L, Dubois V, Congy-Jolivet N, Visentin J, Danjoux M, Le Bail B, Hervieu V, Boillot O, Antonini T, Kamar N, Dumortier J. Outcome of Liver Transplant Patients With Preformed Donor-Specific Anti-Human Leukocyte Antigen Antibodies. Liver Transpl. 2020;26:256-267. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 15] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Lee CF, Eldeen FZ, Chan KM, Wu TH, Soong RS, Wu TJ, Chou HS, Lee WC. Bortezomib is effective to treat acute humoral rejection after liver transplantation. Transplant Proc. 2012;44:529-531. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 26] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Burghuber CK, Roberts TK, Knechtle SJ. The clinical relevance of alloantibody in liver transplantation. Transplant Rev (Orlando). 2015;29:16-22. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 4] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Loupy A, Lefaucheur C. Antibody-Mediated Rejection of Solid-Organ Allografts. N Engl J Med. 2018;379:1150-1160. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 246] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 284] [Article Influence: 47.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Wozniak LJ, Venick RS. Donor-specific antibodies following liver and intestinal transplantation: Clinical significance, pathogenesis and recommendations. Int Rev Immunol. 2019;38:106-117. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 9] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Kozlowski T, Rubinas T, Nickeleit V, Woosley J, Schmitz J, Collins D, Hayashi P, Passannante A, Andreoni K. Liver allograft antibody-mediated rejection with demonstration of sinusoidal C4d staining and circulating donor-specific antibodies. Liver Transpl. 2011;17:357-368. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 125] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 122] [Article Influence: 9.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Couchonnal E, Rivet C, Ducreux S, Dumortier J, Bosch A, Boillot O, Collardeau-Frachon S, Dubois R, Hervieu V, André P, Scoazec JY, Lachaux A, Dubois V, Guillaud O. Deleterious impact of C3d-binding donor-specific anti-HLA antibodies after pediatric liver transplantation. Transpl Immunol. 2017;45:8-14. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 17] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Ali S, Ormsby A, Shah V, Segovia MC, Kantz KL, Skorupski S, Eisenbrey AB, Mahan M, Huang MA. Significance of complement split product C4d in ABO-compatible liver allograft: diagnosing utility in acute antibody mediated rejection. Transpl Immunol. 2012;26:62-69. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 35] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Demetris AJ, Bellamy C, Hübscher SG, O'Leary J, Randhawa PS, Feng S, Neil D, Colvin RB, McCaughan G, Fung JJ, Del Bello A, Reinholt FP, Haga H, Adeyi O, Czaja AJ, Schiano T, Fiel MI, Smith ML, Sebagh M, Tanigawa RY, Yilmaz F, Alexander G, Baiocchi L, Balasubramanian M, Batal I, Bhan AK, Bucuvalas J, Cerski CTS, Charlotte F, de Vera ME, ElMonayeri M, Fontes P, Furth EE, Gouw ASH, Hafezi-Bakhtiari S, Hart J, Honsova E, Ismail W, Itoh T, Jhala NC, Khettry U, Klintmalm GB, Knechtle S, Koshiba T, Kozlowski T, Lassman CR, Lerut J, Levitsky J, Licini L, Liotta R, Mazariegos G, Minervini MI, Misdraji J, Mohanakumar T, Mölne J, Nasser I, Neuberger J, O'Neil M, Pappo O, Petrovic L, Ruiz P, Sağol Ö, Sanchez Fueyo A, Sasatomi E, Shaked A, Shiller M, Shimizu T, Sis B, Sonzogni A, Stevenson HL, Thung SN, Tisone G, Tsamandas AC, Wernerson A, Wu T, Zeevi A, Zen Y. 2016 Comprehensive Update of the Banff Working Group on Liver Allograft Pathology: Introduction of Antibody-Mediated Rejection. Am J Transplant. 2016;16:2816-2835. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 344] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 361] [Article Influence: 45.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Halle-Smith JM, Hann A, Cain OL, Perera MTPR, Neil DAH. Lactic Acidosis, Hypoglycemia, and Eosinophilia: Novel Markers of Antibody-Mediated Rejection Causing Graft Ischemia. Liver Transpl. 2021;27:1857-1860. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 2] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Baliellas C, Lladó L, Serrano T, Gonzalez-Vilatarsana E, Cachero A, Lopez-Dominguez J, Petit A, Fabregat J. Sinusoidal obstruction syndrome as a manifestation of acute antibody-mediated rejection after liver transplantation. Am J Transplant. 2021;21:3775-3779. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 4] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Della-Guardia B, Almeida MD, Meira-Filho SP, Torres MA, Venco F, Afonso RC, Ferraz-Neto BH. Antibody-mediated rejection: hyperacute rejection reality in liver transplantation? Transplant Proc. 2008;40:870-871. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 15] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Ratner LE, Phelan D, Brunt EM, Mohanakumar T, Hanto DW. Probable antibody-mediated failure of two sequential ABO-compatible hepatic allografts in a single recipient. Transplantation. 1993;55:814-819. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 35] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Zarrinpar A, Busuttil RW. Liver transplantation: Evading antigens-ABO-incompatible liver transplantation. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;12:676-678. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 1] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Rostron A, Carter V, Mutunga M, Cavanagh G, O'Suilleabhain C, Burt A, Jaques B, Talbot D, Manas D. A case of acute humoral rejection in liver transplantation: successful treatment with plasmapheresis and mycophenolate mofetil. Transpl Int. 2005;18:1298-1301. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 28] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Tajima T, Hata K, Okajima H, Nishikori M, Yasuchika K, Kusakabe J, Yoshizawa A, Fukumitsu K, Anazawa T, Tanaka H, Wada S, Doi J, Takaori-Kondo A, Uemoto S. Bortezomib Against Refractory Antibody-Mediated Rejection After ABO-Incompatible Living-Donor Liver Transplantation: Dramatic Effect in Acute-Phase? Transplant Direct. 2019;5:e491. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 16] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Chan KM, Lee CS, Wu TJ, Lee CF, Chen TC, Lee WC. Clinical perspective of acute humoral rejection after blood type-compatible liver transplantation. Transplantation. 2011;91:e29-e30. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 33] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Kamar N, Lavayssière L, Muscari F, Selves J, Guilbeau-Frugier C, Cardeau I, Esposito L, Cointault O, Nogier MB, Peron JM, Otal P, Fort M, Rostaing L. Early plasmapheresis and rituximab for acute humoral rejection after ABO-compatible liver transplantation. World J Gastroenterol. 2009;15:3426-3430. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in CrossRef: 38] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 34] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |