Published online Nov 6, 2020. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v8.i21.5159

Peer-review started: July 6, 2020

First decision: August 8, 2020

Revised: August 18, 2020

Accepted: September 17, 2020

Article in press: September 17, 2020

Published online: November 6, 2020

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is currently the standard investigation for suspected perianal diseases. Carcinoma arising from anal fistula is very rare, and early diagnosis is often difficult.

To describe and summarize the MRI findings of carcinoma arising from anal fistula.

In this retrospective study, records of ten patients diagnosed with carcinoma arising from anal fistula and confirmed by surgery (n = 7) or biopsy (n = 3) between June 2006 and August 2018 were analyzed. All patients underwent preoperative pelvic MRI. Morphologic features, signal characteristics, fistula between the mass and the anus, contrast enhancement of mass, signal and enhancement of peritumoral areas, and regional lymphadenopathy were assessed.

All ten tumors were solitary (8 mucinous adenocarcinomas and 2 adenocarcinomas). The maximum diameter of the tumors ranged from 3.4 cm to 12.4 cm (median: 4.15 cm; mean: 5.68 cm). Eight patients had a fistula between the mass and the anus. Contrast enhancement of the peritumoral areas was noted in three (3/5) patients. Perirectal or inguinal lymphadenopathy was noted in seven patients. Most lesions of mucinous adenocarcinoma were multiloculated and cauliflower-like, with a thin capsule and focally unclear boundary. They were markedly hyperintense on fat-suppressed T2WI, slightly hyperintense with focal hyperintensity on diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI), and hyperintense with focal hypointensity on apparent diffusion coefficient (ADC) map, with progressive mesh-like contrast enhancement. Adenocarcinomas had an infiltrative margin without a capsule and appeared heterogeneously hyperintense or slightly hyperintense on fat-suppressed T2WI, hyperintense on DWI, and hypointense on ADC map, with persistent heterogeneous enhancement.

Our study highlighted several characteristic and potentially helpful MRI findings to diagnose carcinomas arising from anal fistula.

Core Tip: Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is currently the standard investigation for suspected perianal diseases. Carcinoma arising from anal fistula is very rare, and early diagnosis is often difficult. We aimed to describe and summarize the MRI findings of this entity.

- Citation: Zhu X, Zhu TS, Ye DD, Liu SW. Magnetic resonance imaging findings of carcinoma arising from anal fistula: A retrospective study in a single institution. World J Clin Cases 2020; 8(21): 5159-5171

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v8/i21/5159.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v8.i21.5159

Anal carcinomas are rare malignant tumors, accounting for approximately 2%-3% of large-bowel malignancies[1]. A carcinoma arising from an anal fistula is even rarer, and early diagnosis is often difficult[2,3]. The early symptoms of these tumors are similar to common perianal diseases; therefore, they are often wrongly diagnosed as benign lesions. Owing to the delay in diagnosis, patients typically have advanced-stage disease at the time of surgery[4]. Diagnostic confirmation of cancer arising from an anal fistula is through histopathological examination.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is considered the most accurate preoperative technique for classification of anal fistula and is useful for evaluation of the primary track, abscesses, and extensions to adjacent tissues[5-7]. More importantly, it is useful to guide clinicians in determining the extent of surgical resection. Diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI) is already being incorporated into anal cancer MRI protocol as a result of its many clinical advantages[7,8]. Although carcinomas arising from anal fistula have been reported from the perspectives of their clinical features, only few studies have focused on their MRI findings[9-11]. The purpose of this study was to describe the MRI findings in patients with carcinomas arising from anal fistula, and explore more characteristic signs to facilitate the auxiliary diagnosis of this disease.

This retrospective study was approved by the institutional review board of the Affiliated Hospital of Nanjing University of Chinese Medicine, which waived the requirement for informed consent. Between June 2006 and August 2018, ten patients diagnosed with carcinoma arising from anal fistula underwent preoperative pelvic MRI. Age, sex, pathological subtypes, clinical symptoms, duration of anal fistula, and history of surgery were recorded (Table 1). All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and national research committees and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

| Item | Data |

| Age (yr) | 59 ± 12 (31–75) |

| Sex | Male (n = 8); Female (n = 2) |

| Pathological subtypes | Mucinous adenocarcinoma (n = 8); Adenocarcinoma (n = 2); Squamous cell carcinoma (n = 0) |

| Clinical symptoms | Persistent fistula (n = 10); Pain (n = 5); Discharging (n = 5); Enlarging mass (n = 1); Hematochezia (n = 1) |

| Duration of anal fistula | ≤ 10 yr (n = 4); > 10 yr (n = 6) |

| History of operation | Yes (n = 10); No (n = 0) |

MRI was performed either on a 1.5-T system (Aera, Siemens AG, Munich, Germany) (n = 9) or 3.0-T system (Verio, Siemens AG, Munich, Germany) (n = 1). Unenhanced MRI of the pelvis was performed in all the ten patients. In five patients, this was followed by dynamic contrast enhanced (DCE) scans. In the remaining five, this was followed by diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI). All patients were examined using a pelvic phased-array coil. The imaging technique used for pelvic MRI at our institution is provided in Table 2.

| 1.5 T | 3.0 T | |||||||||

| T1WI | T2WI | FS-T2WI | DWI | T1-DCE | T1WI | T2WI | FS-T2WI | DWI | T1-DCE | |

| Imaging plane | Axial | Axial/coronal/sagittal | Axial/coronal/sagittal | Axial | Axial/coronal/sagittal | Axial | Axial/coronal/sagittal | Axial/coronal/sagittal | Axial | Axial/coronal/sagittal |

| TE/TR (ms) | 21/658 | 84/2400 | 80/2530 | 95/5800 | 2.3/4.9 | 12/970 | 93/5600 | 85/3400 | 76/10900 | 1.4/4.0 |

| Field of view (mm) | 220 | 220 | 220 | 220 | 220 | 220 | 220 | 220 | 220 | 220 |

| Matrix size | 256/256 | 256/256 | 256/256 | 256/256 | 256/256 | 416/224 | 416/224 | 416/224 | 416/224 | 416/224 |

| Slice thickness (mm) | 4.0 | 4.0 | 4.0 | 5.0 | 3.0 | 4.0 | 4.0 | 4.0 | 5.0 | 3.0 |

| Intersection gap (mm) | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 |

Carcinoma arising from anal fistula was diagnosed according to Rosser’s criteria: (1) The fistula should usually antedate the carcinoma by at least 10 years; (2) The only tumor present in the rectum or anal canal should be secondary to direct extension from the carcinoma in the fistula; and (3) The internal opening of the fistula should be into the anal canal and not into the tumor itself[12].

Pathological specimens were observed by light microscopy and immunohistochemical analysis. All tumors were confirmed to be carcinomas arising from anal fistula by surgery (n = 7) or biopsy (n = 3). Cases of rectal cancer, malignant signs in the anal mucosa, and the internal opening of fistula into the tumor were excluded before definite diagnosis.

Pelvis MRI images were reviewed and interpreted in consensus by two radiologists with 5 and 20 years of experience, respectively, who were blinded to the histopathologic results. Morphologic features (location, shape, maximum diameter, capsule, and margin); signal characteristics [fat-suppressed T2-weighted MRI (FS-T2WI), DWI, and apparent diffusion coefficient (ADC)]; fistula between the mass and anus; contrast enhancement of mass; signal on FS-T2WI and enhancement of peritumoral areas; and regional lymphadenopathy were assessed on MRI. These features were selected based on the previous literature and our personal experience[9-11].

The capsule was observed as a hypointense area on both T1-weighted magnetic resonance imaging (T1WI) and T2WI. Signal intensity on FS-T2WI was classified as markedly hyperintense, hyperintense, and slightly hyperintense. Marked hyperintensity was defined as signal intensity similar to that of fluid in the bladder. Hyperintensity was defined as signal intensity higher than that of muscle but lower than that of fluid. Slight hyperintensity was defined as signal intensity slightly higher than that of muscle. Fistula between the mass and the anus was defined as a tubular or linear hyperintense communication between the mass and the anus assessed on FS-T2WI.

The enhancement pattern of tumor was assessed on T1-DCE images. We observed the enhancement characteristics of the tumor including the inner edge of the lesion (smooth or rough), enhancement of septum, and unenhanced necrotic area within the lesion. Contrast enhancement of peritumoral areas was also assessed on T1-DCE images. If there was enhancement around the tumor, the signal intensity of this area was observed on FS-T2WI.

Regional lymphadenopathy was defined as perirectal and inguinal lymph nodes > 5 mm in the short axis, morphological change (irregular or round), signal intensity on FS-T2WI, heterogeneous enhancement, or hyperintensity on DWI[13].

The mean age at diagnosis of the ten patients (eight mean and two women) was 59 ± 12 years (age range: 31–75 years; median, 60 years). Most patients (90%) were older than 50 years. Eight patients were diagnosed with mucinous adenocarcinoma and two with adenocarcinoma. Clinical symptoms included persistent fistula in ten patients, pain in five, anal discharge in five, gradually enlarging mass in one, and hematochezia in one. One patient was diagnosed with Crohn’s perianal fistula-associated mucinous adenocarcinoma. Nine patients had long-lasting anal fistulas with durations ranging from 2 to 40 years; six of these patients had anal fistulas lasting more than 10 years. Nine patients had a history of prior surgery (Table 1). Table 3 summarizes the MRI findings of carcinoma arising from anal fistula.

| Pathology | Location | Shape | Maximum diameter of lesion (cm) | Margin and capsule | Signal characteristics | Fistula between mass and anus | Enhancement of tumor | Enhancement and signal on FS-T2WI of peritumoral areas | Regional lymph nodes | |||||

| FS-T2WI | DWI | ADC | Short axis enlargement | Morphology | Signal intensity(FS-T2WI/DWI) | Enhancement | ||||||||

| M | Left | Multilocular, cauliflower-like | 3.6 | Unclear; Yes | Markedly hyperintense | Slightly hyperintense | Hyperintense | Yes | Progressive mesh-like enhancement | No | Yes | Change | Heterogeneous; hyperintense | Yes |

| M | Right | Multilocular, cauliflower-like | 4.7 | Clear; Yes | Markedly hyperintense | Hyperintense | Local hypointense | Yes | __ | __ | Yes | Normal | Heterogeneous; normal | - |

| M | Left | Round | 4.1 | Unclear; No | Slightly hyperintense | __ | __ | Yes | __ | __ | Yes | Change | Heterogeneous; - | - |

| M | Across the midline | Multilocular, cauliflower-like | 10.6 | Unclear; Yes | Markedly hyperintense | __ | __ | Yes | __ | __ | Yes | Change | Heterogeneous; - | - |

| M | Left | Multilocular, cauliflower-like | 12.4 | Unclear; Yes | Markedly hyperintense | __ | __ | Yes | __ | __ | No | Change | Heterogeneous-us; - | - |

| M | Left | Band-like | 3.4 | Unclear; No | Hyperintense | __ | __ | Yes | __ | __ | No | Change | Heterogeneous-us; - | - |

| M | Left | Multilocular, cauliflower-like | 4.3 | Unclear; Yes | Markedly hyperintense | Hyperintense | Local hypointense | Yes | Progressive mesh-like enhancement | Yes | No | Normal | Normal; normal | No |

| M | Across the midline | Multilocular, cauliflower-like | 6.0 | Unclear; Yes | Markedly hyperintense | Hyperintense | Local hypointense | Yes | Progressive mesh-like enhancement | Yes | No | Normal | Heterogeneous-us; normal | No |

| A | Left | Oval | 3.7 | Unclear; No | Slightly hyperintense | Hyperintense | Hypointense | No | Persistent heterogeneous enhancement | Yes | Yes | Change | Heterogeneous-us; hyperintense | Yes |

| A | Right | Oval | 4.0 | Unclear; Yes | Hyperintense | __ | __ | Yes | Persistent heterogeneous enhancement | Yes | Yes | Change | Heterogeneous-us; - | Yes |

Location of tumor: Six lesions were on the left, two on the right, and two grew across the midline (Figure 1).

Shape and maximum diameter of lesions: The lesions were multiloculated and cauliflower-like (n = 6), round or oval (n = 3), and band-like (n = 1) in shape. The maximum diameter of the tumors ranged from 3.4 to 12.4 cm (median: 4.15 cm; mean: 5.68 cm) on FS-T2WI.

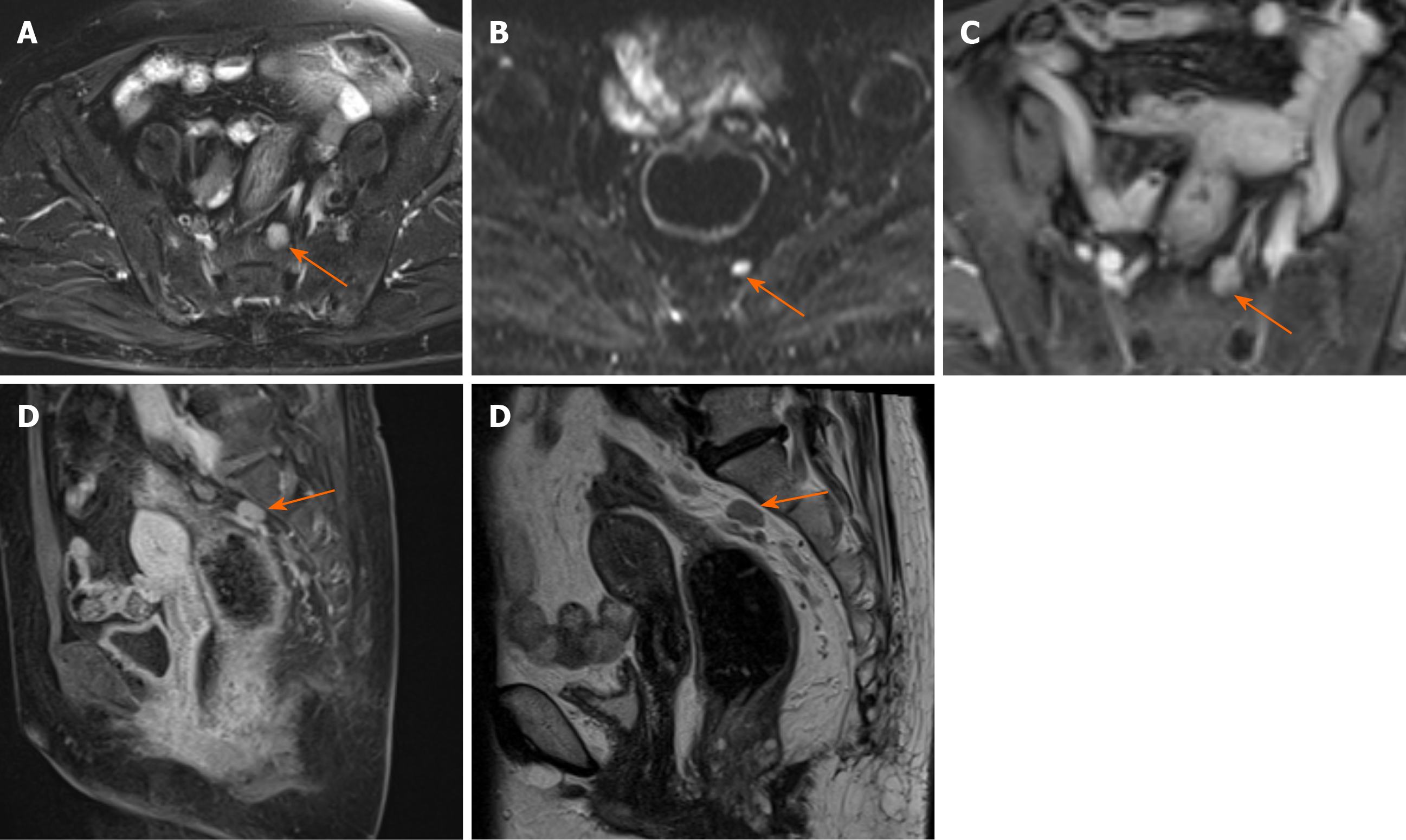

Margin and capsule: Seven lesions with mucinous adenocarcinoma had a thin capsule, unlike the thick fibrous capsule of a fistula, and the focal boundary of tumors was unclear (Figures 1 and 3). The remaining three lesions (one mucinous adenocarcinoma and two adenocarcinomas) had an infiltrative margin without capsule (Figure 2).

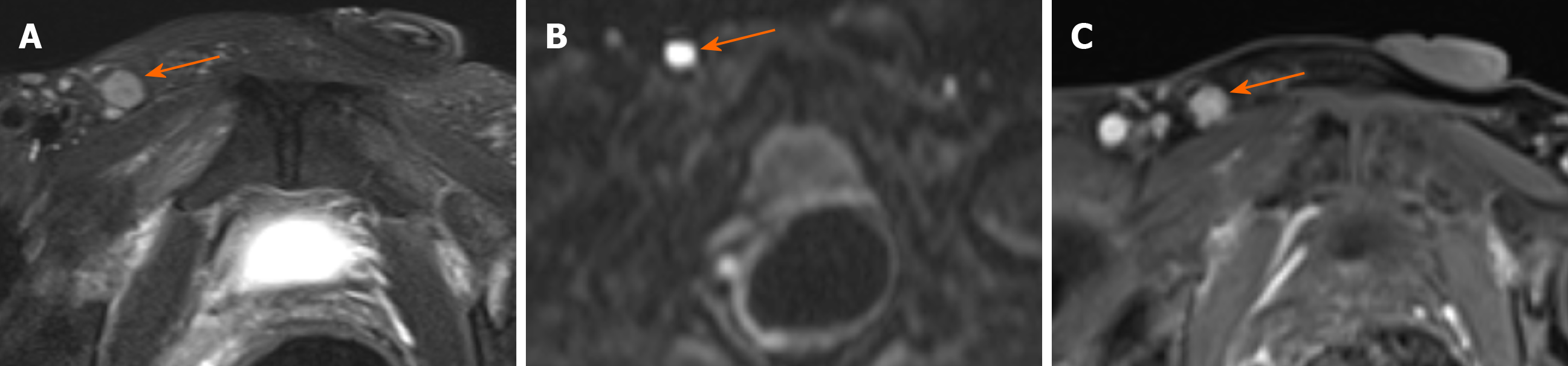

Signal on FS-T2WI, diffusion-weighted imaging, and apparent diffusion coefficient map: Among the eight patients with mucinous adenocarcinoma, six showed markedly hyperintense, one showed hyperintense, and one showed slightly hyperintense signal on FS-T2WI images (Figures 1 and 3). In two patients with adenocarcinoma, tumors appeared as heterogeneously hyperintense or slightly hyperintense signals (Figure 2). Only five patients’ MRI sequences had included DWI, including four with mucinous adenocarcinoma and one with adenocarcinoma. Of the four patients with mucinous adenocarcinoma, two patients’ lesions presented as slightly hyperintense with focal hyperintense signal on DWI and hyperintense with focal hypointense signal on ADC map (Figures 1 and 3); the remaining two patients’ lesions showed slightly hyperintense signal on DWI and hyperintense signal on ADC map. One patient with adenocarcinoma showed lesions that presented as hyperintense on DWI and hypointense signal on ADC map (Figure 2).

Fistula between mass and anus: A fistula between the mass and anus was detected in six patients with mucinous adenocarcinoma and two with adenocarcinoma (Figure 2). In two patients with mucinous adenocarcinoma, the masses surrounded the anal canal and appeared to be connected to it.

Contrast enhancement of tumor: Only five patients received contrast material for MRI studies. The lesions of three patients with mucinous adenocarcinoma appeared as progressive mesh-like contrast enhancement or septal enhancement, and the inner margin of the lesion was rough (Figure 1). The lesions of two patients with adenocarcinoma presented with persistent heterogeneous enhancement (Figure 2), and the necrotic areas were unenhanced.

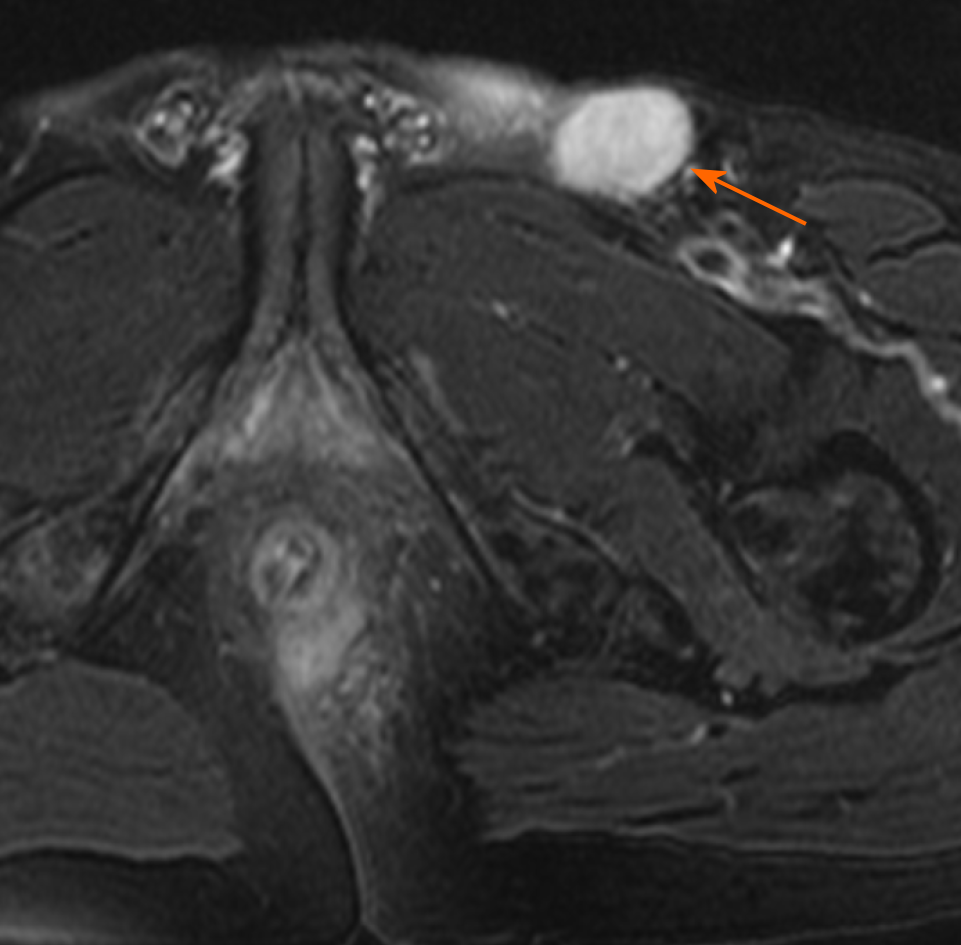

Contrast enhancement of peritumoral areas: Contrast enhancement of the peritumoral areas was noted in three of five patients who received contrast material. The boundary of the enhanced region was not clear and presented as slightly higher signal on FS-T2W I (Figure 4).

Regional lymphadenopathy: Perirectal and inguinal lymphadenopathy was noted in two of ten patients, and only inguinal lymphadenopathy was noted in five of ten patients. In the remaining three patients, small lymph nodes were seen around the rectum or inguinal region (Figure 5, Figure 6,Figure 7).

Carcinoma arising from an anal fistula is extremely rare. It was first reported by Rosser in 1934[12], and there have been few reported case series in the literature since then. The early diagnosis of carcinoma arising from anal fistula is very difficult either because the clinical manifestations are nonspecific and/or similar to the typical symptoms of perianal disease or because the tumor is very slow growing[14]. The risk of malignant transformation of chronic recurrent anal fistula should be seriously considered. When doctors are highly suspicious of malignant lesions, regular surveillance is recommended in chronic recurrent anorectal fistulas, and aggressive methods to rule out cancer are necessary.

The pathogenesis of carcinoma arising from anal fistula is not yet definite, but is believed to involve the following aspects: (1) Long-term recurrent chronic inflammatory stimulation and alienation of scar tissue; (2) Infection with HPV in patients with squamous cell carcinoma; and (3) Long-standing immunosuppression in patients with Crohn perianal disease[15].

A previous report suggested that this condition is slightly more common in men, with the average age at diagnosis being 55 years[11]. Our results were consistent with this report, given that most of our patients were male (8/10), and most of the patients were middle-aged or elderly (9/10; age range: 50-75 years).

There are three main pathological subtypes of carcinoma arising from an anal fistula—mucinous adenocarcinoma, adenocarcinoma, and squamous cell carcinoma[16-19]. Thomas et al[15] stated that the histology of adenocarcinoma was the most common (~59%); however, mucinous adenocarcinoma was the most common pathological type in our study (8/10). The possible reason is that previous studies considered only two major types, namely, adenocarcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma, and mucinous adenocarcinoma was classified as adenocarcinoma.

Early symptoms of carcinoma arising from anal fistula are similar to those of anal fistula or perianal abscess, usually without diarrhea or obstruction, which may help to distinguish from rectal cancer. Digital examination may reveal only an area of induration on the side where the fistula is situated. Six patients completely fulfilled the above criteria in our study, while in the remaining four patients, the anal fistula has been present < 10 years. To ascertain whether the standard “the fistula should usually antedate the carcinoma by at least 10 years” is still decisive, it is necessary to analyze a larger group of patients.

Abdominoperineal resection (APR) is the most common surgical treatment for this rare malignancy, and the effect of radiotherapy and chemotherapy is still controversial[15,17]. Prognosis of carcinoma arising from anal fistula is usually poor[20].

The masses could be unilateral or grow across the midline and typically surrounded the anal canal. The size of the tumor lesion could be relatively large. The mean of the maximum lesion diameter was 5.68 cm in our patients, and even exceeded 10 cm in two casas. In our study, the typical features of mucinous adenocarcinoma with respect to shape were multiloculated or cauliflower-like with internal septa. Hama et al[10] hypothesized that the mucin pools produced by a mucinous adenocarcinoma without thick fibrous capsule may reflect that cancer cells have invaded the surrounding tissues before the fibrotic reaction. However, the perianal fistulas or abscess whose mucin was secreted by the anal gland had a thick fibrous capsule. We speculated that the thin capsule could still be seen in a mucinous adenocarcinoma, and the focal boundary of tumors was unclear, which could reflect the invasive nature. Adenocarcinoma lesions appeared ill-defined and had no capsule. Because of the small number of adenocarcinoma cases, the relevant characteristics could not be effectively summarized.

Mucinous adenocarcinoma mostly presented with markedly hyperintense signals on T2-weighted MR images, slightly hyperintense signals on DWI, and hyperintense signals on ADC map, which represented the signal of mucin pool. Some lesions of mucinous adenocarcinoma contained solid components, showing focal slightly hyperintense signal on FS-T2WI, hyperintense signals on DWI, and hypointense signals on ADC map. Adenocarcinoma showed heterogeneous high or slightly high signal on FS-T2WI, high signal on DWI, and low signal on ADC map.

Hama et al[10] reported that a fistula between the mass and the anus is a characteristic finding of mucinous adenocarcinoma arising from an anal fistula. Our results are consistent with this conclusion because eight patients had a fistula between the mass and the anus, and two patients showed the masses surrounding the anal canal and appearing to be connected to the canal. Because of the history of anal fistula in all patients, whether the fistulas between the mass and the anus were caused by the tumor or the previous anal fistula remains to be further explored. At present, we are inclined to the latter possibility.

The lesions of mucinous adenocarcinoma showed progressively mesh-like contrast enhancement, septal enhancement, and rough inner margin. Although the number of patients with post-contrast MRI scan was small, the results were basically consistent with those reported in the literature[10]. Meanwhile, we considered that the progressively enhanced pattern was similar to that of the fiber, which was indicative of the existence of an internal septum and thin capsule. Adenocarcinomas presented with persistent heterogeneous enhancement.

Contrast enhancement of the peritumoral areas was noted in three of our cases. Hama et al[10] believed that this could be a reliable finding reflecting the invasion of cancer cells. We found it challenging to distinguish contrast enhancement from enhancement of active inflammation. Considering the unclear boundary and the slightly hyperintense signal on FS-T2WI of the enhanced region, we suspected that the tumor invasion and inflammation were coexisting conditions. We recommend MRI re-examination after remission of inflammation.

Perirectal or inguinal lymphadenopathy was noted in seven of ten patients in our study. Unfortunately, pathologic confirmation could not be obtained. Iesalnieks et al[21] found that approximately 50% appeared inguinal lymph node involvement and about 10% presented with distant organ metastasis. Therefore, we believe that the signs of lymph nodes are helpful in the diagnosis of carcinoma arising from anal fistula.

Perianal abscess is often accompanied with anal fistula; therefore, it is considered as the main differential diagnosis of mucinous adenocarcinoma arising from the anal fistula. Perianal abscess could be unilocular or multilocular and is typically associated with active inflammation. It presents higher signal intensity and lower signal intensity than mucinous adenocarcinoma on DWI and ADC maps. Essentially, the abscess usually demonstrates ring-enhancement without containing solid components.

The fistula between the mass and the anus and the history of long-standing chronic anal fistula could be helpful to distinguish between mucinous adenocarcinoma arising from anal fistula and malignant transformation of cystic lesions in the pelvic cavity, such as a tailgut cyst, teratoma, or dermoid cyst[10].

Our study has some limitations. First, this was a retrospective study of patients from a single institution. Second, carcinoma arising from anal fistula is a rare diagnosis, and the sample size is therefore relatively small. It remains to be further analyzed whether imaging features of lesions could be completely summarized. Third, the included patients had a relatively long time span (between June 2006 and August 2018), and the corresponding MRI techniques were therefore not consistent.

In conclusion, despite the first negative biopsies, clinicians should be highly suspicious of cancer in patients with chronic perineal fistulas whose symptoms change, and a repeat biopsy should be recommended. The definitive diagnosis of cancer arising from an anal fistula is always challenging. Therefore, multiple, repeated, and deep biopsies are essential for accurate and timely diagnosis. Although the number of cases was inadequate owing to the rarity of the disease, we believe that several characteristic MRI findings could contribute to accurate and timely diagnosis of carcinoma arising from anal fistula.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is the standard investigation for suspected perianal diseases. This is important to early diagnose carcinoma arising from anal fistula, even if the incidence is low.

To describe and summarize the MRI findings of carcinoma arising from anal fistula.

To summarize the MRI manifestations of carcinoma arising from anal fistula to help improve the ability to diagnose this entity.

A retrospective study was performed on ten patients diagnosed with carcinoma arising from anal fistula and confirmed by pathological diagnosis between June 2006 and August 2018. All patients underwent preoperative pelvic MRI. Five patients underwent enhanced MRI scans. Rosser’s criteria were used for diagnosing carcinoma arising from anal fistula. Morphologic features, signal characteristics, fistula between the mass and the anus, contrast enhancement of mass, signal and enhancement of peritumoral areas, and regional lymphadenopathy were assessed.

Most patients (90%) were older than 50 years. There were eight mucinous adenocarcinomas and two adenocarcinomas. The maximum diameter of the tumors ranged from 3.4 cm to 12.4 cm (median: 4.15 cm; mean: 5.68 cm). Eight patients had a fistula between the mass and the anus. Perirectal or inguinal lymphadenopathy was frequent (7/10).

Most lesions of mucinous adenocarcinoma were multiloculated and cauliflower-like, with a thin capsule and focally unclear boundary. They were markedly hyperintense on fat-suppressed T2WI, slightly hyperintense with focal hyperintense on diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI), and hyperintense with focal hypointensity on apparent diffusion coefficient (ADC) map, with progressive mesh-like contrast enhancement.

Adenocarcinomas had an infiltrative margin without a capsule and appeared heterogeneously hyperintense or slightly hyperintense on fat-suppressed T2WI, hyperintense on DWI, and hypointense on ADC map, with persistent heterogeneous enhancement.

A negative biopsy does not rule out the diagnosis of cancer, clinicians should be highly suspicious of cancer in patients with chronic perineal fistulas whose symptoms change, and a repeat biopsy should be recommended. The definitive diagnosis of cancer arising from an anal fistula is always challenging. Although the number of cases was inadequate owing to the rarity of the disease, we believe that several characteristic MRI findings could contribute to accurate and timely diagnosis of carcinoma arising from anal fistula in selection of puncture route and screening of high-risk groups.

Earlier and better identification and monitoring of high-risk groups of carcinoma arising from anal fistula are required.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Morelli L S-Editor: Wang DM L-Editor: Wang TQ P-Editor: Li JH

| 1. | Santos MD, Nogueira C, Lopes C. Mucinous adenocarcinoma arising in chronic perianal fistula: good results with neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy followed by surgery. Case Rep Surg. 2014;2014:386150. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 12] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Shwaartz C, Munger JA, Deliz JR, Bornstein JE, Gorfine SR, Chessin DB, Popowich DA, Bauer JJ. Fistula-Associated Anorectal Cancer in the Setting of Crohn's Disease. Dis Colon Rectum. 2016;59:1168-1173. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 26] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Alvarez-Laso CJ, Moral S, Rodríguez D, Carrocera A, Azcano E, Cabrera A, Rodríguez R. Mucinous adenocarcinoma on perianal fistula. A rising entity? Clin Transl Oncol. 2018;20:666-669. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 10] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Inoue Y, Kawamoto A, Okigami M, Okugawa Y, Hiro J, Toiyama Y, Tanaka K, Uchida K, Mohri Y, Kusunoki M. Multimodality therapy in fistula-associated perianal mucinous adenocarcinoma. Am Surg. 2013;79:e286-e288. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 5. | Gecse KB, Bemelman W, Kamm MA, Stoker J, Khanna R, Ng SC, Panés J, van Assche G, Liu Z, Hart A, Levesque BG, D'Haens G; World Gastroenterology Organization, International Organisation for Inflammatory Bowel Diseases IOIBD, European Society of Coloproctology and Robarts Clinical Trials; World Gastroenterology Organization International Organisation for Inflammatory Bowel Diseases IOIBD European Society of Coloproctology and Robarts Clinical Trials. A global consensus on the classification, diagnosis and multidisciplinary treatment of perianal fistulising Crohn's disease. Gut. 2014;63:1381-1392. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 266] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 244] [Article Influence: 24.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Sheedy SP, Bruining DH, Dozois EJ, Faubion WA, Fletcher JG. MR Imaging of Perianal Crohn Disease. Radiology. 2017;282:628-645. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 63] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 65] [Article Influence: 9.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Erden A. MRI of anal canal: common anal and perianal disorders beyond fistulas: Part 2. Abdom Radiol (NY). 2018;43:1353-1367. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 4] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Balcı S, Onur MR, Karaosmanoğlu AD, Karçaaltıncaba M, Akata D, Konan A, Özmen MN. MRI evaluation of anal and perianal diseases. Diagn Interv Radiol. 2019;25:21-27. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 40] [Article Influence: 8.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Fujimoto H, Ikeda M, Shimofusa R, Terauchi M, Eguchi M. Mucinous adenocarcinoma arising from fistula-in-ano: findings on MRI. Eur Radiol. 2003;13:2053-2054. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 12] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Hama Y, Makita K, Yamana T, Dodanuki K. Mucinous adenocarcinoma arising from fistula in ano: MRI findings. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2006;187:517-521. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 34] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Ho CM, Tan CH, Ho BC. Clinics in diagnostic imaging (143). Perianal mucinous adenocarcinoma arising from chronic fistula-in-ano. Singapore Med J. 2012;53:843-8; quiz p. 849. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 12. | Yang BL, Shao WJ, Sun GD, Chen YQ, Huang JC. Perianal mucinous adenocarcinoma arising from chronic anorectal fistulae: a review from single institution. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2009;24:1001-1006. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 36] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Ogawa S, Hida J, Ike H, Kinugasa T, Ota M, Shinto E, Itabashi M, Kameoka S, Sugihara K. Selection of Lymph Node-Positive Cases Based on Perirectal and Lateral Pelvic Lymph Nodes Using Magnetic Resonance Imaging: Study of the Japanese Society for Cancer of the Colon and Rectum. Ann Surg Oncol. 2016;23:1187-1194. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 50] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 54] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Alcalde-Vargas A, Trigo-Salado C, Leo-Carnerero E, Castell-Monsalve FJ, Mateo-Vico O, Márquez-Galán JL. Severe perianal disease degenerated to adenocarcinoma. Is close monitoring of long-term perianal disease necessary? Rev Esp Enferm Dig. 2013;105:115-116. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 5] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Thomas M, Bienkowski R, Vandermeer TJ, Trostle D, Cagir B. Malignant transformation in perianal fistulas of Crohn's disease: a systematic review of literature. J Gastrointest Surg. 2010;14:66-73. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 73] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 67] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Massit H, Edderai M, Saouab R, Seddik H, El Fenni J, Benkirane A. Adenocarcinoma arising from chronic perianal crohn's disease: a case report. Pan Afr Med J. 2015;22:140. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 3] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Chrysikos D, Mariolis-Sapsakos T, Triantafyllou T, Karampelias V, Mitrousias A, Theodoropoulos G. Laparoscopic abdominoperineal resection for the treatment of a mucinous adenocarcinoma associated with an anal fistula. J Surg Case Rep. 2018;2018:rjy036. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 5] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Benjelloun el B, Abkari M, Ousadden A, Ait Taleb K. Squamous cell carcinoma associated anal fistulas in Crohn's disease unique case report with literature review. J Crohns Colitis. 2013;7:e232-e235. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 19] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Seya T, Tanaka N, Shinji S, Yokoi K, Oguro T, Oaki Y, Ishiwata T, Naito Z, Tajiri T. Squamous cell carcinoma arising from recurrent anal fistula. J Nippon Med Sch. 2007;74:319-324. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 12] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Scharl M, Frei P, Frei SM, Biedermann L, Weber A, Rogler G. Epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition in a fistula-associated anal adenocarcinoma in a patient with long-standing Crohn's disease. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;26:114-118. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 28] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Iesalnieks I, Gaertner WB, Glass H, Strauch U, Hipp M, Agha A, Schlitt HJ. Fistula-associated anal adenocarcinoma in Crohn's disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2010;16:1643-1648. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 67] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 58] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |