Management of Zygomatic Arch Fracture in Polycythemia Vera Patient-A Case Report

R.S.G. Satyasai , Prasanna Patruni , Nagasai K* , Sravani P , Meghana V and Divya P

1Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery, Vishnu Dental College, Bhimavaram, West Godavari district, Andhra Pradesh India .

Corresponding author Email: prasannapatruni@gmail.com

DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.12944/EDJ.04.02.03

Copy the following to cite this article:

Satyasai R. S. G, Patruni P, Nagasai K, Sravani P, Meghana V, Divya P. Management of Zygomatic Arch Fracture in Polycythemia Vera Patient-A Case Report. Enviro Dental Journal 2022; 4(2). DOI:http://dx.doi.org/10.12944/EDJ.04.02.03

Copy the following to cite this URL:

Satyasai R. S. G, Patruni P, Nagasai K, Sravani P, Meghana V, Divya P. Management of Zygomatic Arch Fracture in Polycythemia Vera Patient-A Case Report. Enviro Dental Journal 2022; 4(2). Available From: https://bit.ly/3ZIyWZa

Download article (pdf) Citation Manager

Select type of program for download

| Endnote EndNote format (Mac & Win) | |

| Reference Manager Ris format (Win only) | |

| Procite Ris format (Win only) | |

| Medlars Format | |

| RefWorks Format RefWorks format (Mac & Win) | |

| BibTex Format BibTex format (Mac & Win) |

Article Publishing History

| Received: | 20-10-2022 |

|---|---|

| Accepted: | 13-01-2023 |

| Reviewed by: |

Hala M. Abdel-Alim

Hala M. Abdel-Alim |

| Second Review by: |

Anil Pandey

Anil Pandey |

| Final Approval by: | Dr. Shadia Elsayed |

Introduction

The first description of PV appeared in 18921. In 1951, PV and associated diseases were referred to as "myeloproliferative disorders" (MPDs). To reflect the consensus that these disorders constitute neoplasms 1, the WHO reclassified MPD as "myeloproliferative neoplasms" (MPN) in 2008. PV is a rare chronic disease that causes myeloproliferation. Because RBCs are produced in excess in the bone marrow compared to white blood cells and platelets an abnormally high number of RBCs circulate in the blood1, resulting in hyper viscosity and a greater risk for thrombosis 1. Due to the built-in thrombogenic potential of the blood, there is an increased risk of myocardial infarction, heart attack, cerebrovascular events, pulmonary infarctions, deep vein thrombosis, and portal hypertension. Perioperative monitoring of these patients is essential to avoid complications. To avoid complications, it is important to consider prophylactic procedures before surgery3. Therapeutic phlebotomy, hemodilution, and antiplatelet therapy are suggested and mostly used as prophylactic procedures recommended during the perioperative period. The primary outcomes considered in the management are to enhance the health benefits1 while minimizing negative effects by encouraging procedures1 to be performed at appropriate times with appropriate precautions1.

Case report

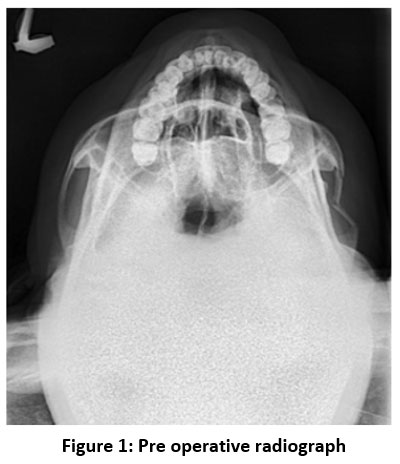

A 30-year-old male patient presented to oral surgery department with a chief complaint of pain on the right side of his face for 3 days. He gave an alleged history of trauma from a loose ceiling fan falling on his face. There was no loss of consciousness or bleeding from the ear, nose, or mouth. The medical and surgical history was unremarkable, and his vital signs were within normal limits. There has been a history of smoking and alcohol consumption for the past 12 years. On extraoral examination, he had a restricted mouth opening of 2.5 cm. Tenderness, crepitus, and depression were noted in the preauricular and temporal regions on the right side of the face. On intraoral examination, the occlusion was satisfactory. Radiographic examination using a submentovertex view (SMV) (Fig. 1) revealed a fracture of the right zygomatic arch.

A routine preoperative workup including a complete blood count, coagulation profile, and viral markers was performed, revealing a hemoglobin (Hb) level of 20.2 g/dL, a hematocrit1 of 58.6%, a total RBC count of 6.44 million/cumm, an RDW-CV of 14.3%. Total white blood cell and platelet counts, as well as bleeding and clotting times, were all within the normal range. To exclude technical errors, the whole blood count was repeated in another laboratory, and the results were consistent with the previous values. The blood erythropoietin level was normal. Arterial blood gas analysis (ABG) revealed that the patient's oxygenation was normal. The patient denied any recent vomiting or diarrhea, living at high altitudes, or with congenital diseases. The patient was referred to a physician for further evaluation. He was also advised to have a chest X-ray, an ECG, liver and renal function tests7, all of which came back normal. Considering the history, clinical, and lab findings, the patient was diagnosed as suffering from polycythemia vera. The treatment plan was discussed with the primary care physician, and after obtaining eligibility for surgery, the case was scheduled for zygomatic arch reduction under local anesthesia. Considering the thrombogenic potential of the blood, preoperative therapeutic phlebotomy (about 350 mL) to reduce the hematocrit to 40%, antiplatelet treatment with Aspirin 150 mg, 12th hourly, was started on the preoperative day and continued until the first postoperative day as recommended by the physician. On the day of surgery, the patient was advised to drink plenty of fluids, and 1 pint of DNS and NS were infused for hemodilution before surgery.

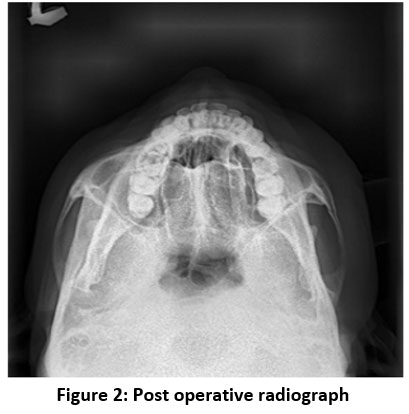

An intraoral vestibular incision was placed in the maxillary right molar area. Dissection was performed to reach the zygomatic arch. The Rowe Zygomatic elevator was passed under the zygomatic arch, and the arch was elevated. A mouth opening of 5 cm was achieved and the stability of the reduced arch was checked using extraoral digital pressure. The incision was closed with 3-0 vicryl round body absorbable sutures. The reduction was confirmed by radiograph (SMV) (Fig. 2) and compared with the preoperative radiograph.

|

Figure 1: Pre operative radiograph |

|

Figure 2: Post operative radiograph |

There were no intraoperative complications; the patient was transferred to the recovery room and hemodynamic parameters were carefully monitored 1. Intraoperative blood loss was calculated, and crystalloids were used to replace it. He was discharged on the third postoperative day with satisfactory healing and was advised to quit smoking, undergo therapeutic phlebotomy, and have a biannual medical check-up. The sutures were removed after 10 days, and there were no postoperative complications during follow-up visits.

Discussion

Maxillofacial surgery has advanced to the point where patients with intricate bleeding diathesis can undergo various surgical procedures safely5. Providing patient care is challenging especially when there is unexpected hemorrhage clinically. This can occur in two ways: intraoperatively or postoperatively. Because of the extensive vasculature in the head and neck area6, as well as limited access through intra-oral sites, most maxillofacial procedures are associated with intra- or post-operative bleeding. In an otherwise healthy patient, this bleeding is self-limiting or controllable7. However, the risk of bleeding increases in patients with bleeding disorders, where even minor procedures can cause prolonged bleeding episodes 1.

Polycythemia vera (PV) is caused by a mutation in the JAK-2 gene. The etiology of the disease is unknown. The disease is rare, with an incidence of 0.7–2.6/1 lakh people annually. Men are more commonly affected than women, and the incidence increases with age. PV can occur spontaneously (primarily) due to genetic abnormalities or secondarily due to a long-term lack of oxygen, such as at high altitudes or from cigarette smoking, also known as smoker's polycythemia or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease8. The signs and symptoms of the disease are shown in Table 1. The cause of the disease in this case was unknown. However, chronic smoking was thought to be a contributing factor and was provisionally diagnosed as secondary polycythemia vera.

Table 1: Signs and Symptoms of Polycythemia Vera 9

|

SYMPTOMS |

SIGNS |

|

More common

Less common

|

|

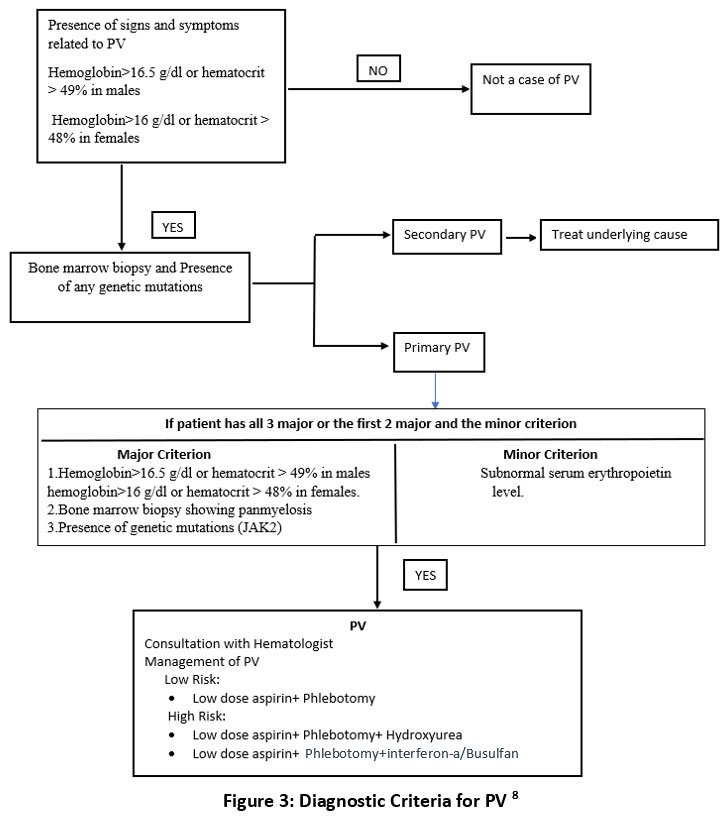

Polycythemia vera (PV) causes an increase in erythrocyte count i, e. 6 to 12 million/mm, and Hb level greater than 18-24 gm/dL, resulting in increased viscosity of blood and thrombosis1. The disease is considered PV when hematocrit is greater than 48% in females and greater than 52% in males. With a hematocrit greater than 55%, there is a significant increase in blood viscosity, which is thrombogenic, as a result, atherosclerosis and cardiovascular disease are more likely to occur. Hematocrit beyond 60% can be fatal and put the patient at risk for arterial as well as venous thrombosis. Leukocytosis and thrombocytosis may also be present. The diagnostic criteria are explained in Figure 3

|

Figure 3: Diagnostic Criteria for PV 8 Click here to view Figure |

Surgeons and anesthesiologists must deal with a PV patient whose capacity to endure surgery is hampered by hematologic abnormalities. The most prevalent cause of hypoxia in these individuals is increased blood viscosity1,7. These surgical patients are at an elevated risk of perioperative thrombosis and bleeding diathesis7, which can be reduced by therapeutic phlebotomy and avoidance of extreme dehydration7. A dislodged thrombus can cause several life-threatening conditions such as myocardial infarction, pulmonary infarctions, cerebrovascular events and so on11. Inadequate control of the thrombogenic tendency can thus lead to life-threatening conditions. A preoperative ECG is mandatory to rule out cardiovascular abnormalities. In such conditions, various techniques have been proposed to reduce the thrombogenic tendency of blood. These include hemodilution, therapeutic phlebotomy, antiplatelet therapy, myelosuppressive therapy, interferon alfa, etc.5,9. However, myelosuppressive therapy is known to transform polycythemia into leukemia. Patients with polycythemia vera can be divided into low-risk (i e.with a history of thrombosis, age > 60 years) and high-risk (no history of thrombosis, age < 60) groups. In our case, the patient can be classified as low risk because there is no previous history of thrombosis and his age is less than 60 years. Myelosuppressive treatment is indicated only in high-risk patients10 . Therapeutic phlebotomy and antiplatelet treatment without myelosuppressive treatment were therefore recommended for this patient.

Patients suffering from PV who undergo surgery are at a greater risk for bleeding and thrombosis. Consequently, it is critical to screen the patients preoperatively to ensure that abnormal counts are optimized to balance the urgency of surgery against the risk i, e. bleeding, and thrombosis. Perioperative management include7

• Involvement of the hematologist to optimize count control and tailor the perioperative plan.

• Using standard protocols for antithrombotic prophylaxis.

• The patient should undergo preoperative screening for coagulation tests, aVWS, and platelet function tests if he or she has a history of bleeding.

Conclusion

To summarize elevated hematocrit, normal arterial oxygenation, and normal erythropoietin levels20 indicate PV7. It is crucial to recognize a patient with PV because avoiding hypoxia is a critical component of ideal anesthesia 1. Managing such patients successfully requires phlebotomy, adequate hydration, and recognition of thrombotic and bleeding problems. It is imperative to perform this duty with sound clinical judgment and a thorough understanding of the pathophysiology of PV20. This case report demonstrates that a complex procedure such as the treatment of maxillofacial trauma can be performed safely in patients with PV.

Acknowledgment

The author would like to thank the head of the Department and faculty members of the Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery Vishnu Dental College for their guidance and support to complete this article.

Conflict of Interest

There is no conflict of Interest.

Funding Source

There is no financial or funding support for this article.

References

- Grover HS, Kapoor S, Kaushik N. Polycythemia vera dental management -case report. J Anesth Crit Care Open Access. 2016;5(2):11?12. DOI: 10.15406/jaccoa.2016.05.00177

CrossRef - Lu X, Chang R. Polycythemia Vera. 2022 Apr 28. In: Stat Pearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): Stat Pearls Publishing; 2022 Jan–. PMID: 32491592.

- Adam AA, Zhi L, Bing LZ, Zhong Xing WU. Evaluation of treatment of zygomatic bone and zygomatic arch fractures: a retrospective study of 10 years. J Maxillofacial Oral Surg. 2012 Jun;11(2):171-6. Doi: 10.1007/s12663-011-0294-x.

CrossRef - Wilson, Damien Jonas. (2019, February 27). Zygomatic Fractures. News-Medical. Retrieved on October 19, 2022, from https://www.news-medical.net/health/Zygomatic-Fractures.aspx.

- Lichtman MA, Beutler E, Kipps TJ, Seligsohn U, et al. Eds. Williams Hematology. 7th ed. McGraw-Hill Companies. New York, NY; 2006:779-803.

- Amat, Shaila; Deepa, C; Priolkar, Samita; Nazareth, Marilyn (2012). A case of polycythemia vera for orthopedic surgery: Perianesthetic considerations. Saudi Journal of Anaesthesia, 6(1), 87–. doi:10.4103/1658-354x.93077

CrossRef - Aliabadi E, Malekpour B, Tavanafar S, Karimpour H, Parvan M. Intraoperative Blood Loss in Maxillofacial Trauma Surgery. Ann Maxillofac Surg. 2020;10(1):164-167. doi: 10.4103/ams.ams_165_19

CrossRef - Brian J. Stuart, Lt, Mc, Usnr, And Anthony J. Viera, Lcdr, Mc, Usnr Am Fam Physician. 2004;69(9):2139-2144

- Iurlo, Alessandra & Cattaneo, Daniele & Bucelli, Cristina & Baldini, Luca. (2020). New Perspectives on Polycythemia Vera: From Diagnosis to Therapy. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 21. 5805. 10.3390/ijms21165805.

CrossRef - Tefferi, Ayalew & Vannucchi, Alessandro & Barbui, Tiziano.Polycythemia vera treatment algorithm, Blood Cancer Journal 2018 doi: 8. 10.1038/s41408-017-0042-7.

CrossRef - Hans Carl Hasselbalch. Smoking as a contributing factor for the development of polycythemia vera and related neoplasms, Leukemia Research, Volume 39, Issue 11, 2015, Pages 1137-1145

CrossRef - Raedler LA. Diagnosis and Management of Polycythemia Vera: Proceedings from a Multidisciplinary Roundtable. Am Health Drug Benefits. Oct;7(7 Suppl 3):S36-47 2014

- Stuart, Brian J, and Anthony J Viera. "Polycythemia vera." American family physician 69 9 (2004): 2139-44

- Tefferi A, Barbui T. Polycythemia vera and essential thrombocythemia: 2019 update on diagnosis, risk-stratification and management. Am J Hematol. 2019 Jan;94(1):133-143.

CrossRef - Cerquozzi S, Barraco D, Lasho T, Finke C, Hanson CA, Ketterling RP, Pardanani A, Gangat N, Tefferi A. Risk factors for arterial versus venous thrombosis in polycythemia vera: a single center experience in 587 patients. Blood Cancer J. 2017 Dec 27;7(12):662. doi: 10.1038/s41408-017-0035-6.

CrossRef - cansa.org.za

- Bergeron JM, Raggio BS. Zygomatic Arch Fracture. [Updated 2022 Jun 27]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2022

- Agrawal, Mohit, Hu Weihsin, Abhishek Pandey, and Balram Garg. "Benign cementoblastoma : a case report with review of the literature", Egyptian Journal of Oral &Maxillofacial Surgery, 2014.

CrossRef - Vaibhav Jain, Himani Garg. "Intra-oral reduction of zygomatic fractures", Dental Traumatology, 2017

- Shaila Kamat, C. Deepa, Samita Priolkar, Marilyn Nazareth. "A case of polycythemia vera fororthopedic surgery: Perianesthetic considerations", Saudi Journal of Anaesthesia.

.jpg)