Understanding the Durability of the Paul Biya Regime in Cameroon: A Micro-Level Approach Using Afrobarometer's Round 7 National Survey

Adrien M. Ratsimbaharison1  and Benn L. Bongang2

and Benn L. Bongang2

1Benedict College, Columbia, SC .

2Savannah State University, Savannah, GA .

DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.12944/CRJSSH.5.2.04

Copy the following to cite this article:

Ratsimbaharison A. M. Understanding the Durability of the Paul Biya Regime in Cameroon: A Micro-Level Approach Using Afrobarometer's Round 7 National Survey. Current Research Journal of Social Sciences and Humanities. 2022 5(2). DOI:http://dx.doi.org/10.12944/CRJSSH.5.2.04

Copy the following to cite this URL:

Ratsimbaharison A. M. Understanding the Durability of the Paul Biya Regime in Cameroon: A Micro-Level Approach Using Afrobarometer's Round 7 National Survey. Current Research Journal of Social Sciences and Humanities. 2022 5(2). Available from:https://bit.ly/3spdLMs

Download article (pdf) Citation Manager Review / Publish History

Select type of program for download

| Endnote EndNote format (Mac & Win) | |

| Reference Manager Ris format (Win only) | |

| Procite Ris format (Win only) | |

| Medlars Format | |

| RefWorks Format RefWorks format (Mac & Win) | |

| BibTex Format BibTex format (Mac & Win) |

Article Review / Publishing History

| Received: | 05-09-2022 | |

|---|---|---|

| Accepted: | 13-10-2022 | |

| Reviewed by: | Ramzi Bendebka | |

| Second Review by: | Maja Savevska | |

| Final Approval by: | Dr Riccardo Pelizzo | |

Introduction

In 2022, President Paul Biya celebrated 40 years as president of Cameroon, after serving as prime minister for ten years and taking over from President Ahmadou Ahidjo in 1982. This durability made him the longest-ruling non-royal national leader of the world (Tchouteu, J., Chouteu-Chando, J., & Chando, J. T., 2018). Given that his regime was built on a somewhat shaky foundation, his political survival has surprised many observers

Biya began service in leadership positions at Cameroon's independence in 1960. First, as a senior civil servant following his studies in France, he rose to become a close confidant to the first president of the country, Ahmadou Ahidjo. Next, among many other high-ranking positions, he served as secretary-general to Ahidjo's presidency, then as prime minister in 1975, and finally as president in 1982. In 2018, he was reelected for another seven-year term as president (Njoh, 2006; Tchouteu et al., 2018).

Biya survived an attempt by Ahidjo loyalists in April 1984 to oust him from power. In October 1992, when multiparty elections were held, he also survived a vigorous challenge by the opposition leader, Ni John Fru Ndi. Beginning in 2016, teachers and lawyers of the Anglophone North-West and South-West regions began to challenge the government's attempts to marginalize further their regions and the English language in schools and the courts. The strike actions spiraled into violence as the military brutally attacked civilians, especially when separatists in these regions called for independence and a separate state, Ambazonia. Several hundred people were killed and displaced. Until now, the Paul Biya regime had not taken any viable steps to end the conflict (Amin, 2021).

Many observers of Cameroonian politics are amazed by the durability of the Paul Biya regime. They note the excessive corruption, the poor infrastructure, the human rights violations, attacks on media and journalists, and the reneging on democratic promises. Biya remained in power for several decades despite these reasons (Tchouteu et al., 2017a). Support for the regime, real or manipulated, is observed and can be measured by affirmations of loyalty and support (motions de soutien) to the president often sent and read over government-run national media by traditional rulers, political leaders for the ruling Cameroon Peoples Democratic Movement, CPDM, and by others in business and other groups of the country.

Cameroon was barely a decade in existence as an independent federal republic when Victor T. Levine (1971) noted its political stability and hinted at the potential for future instability inherent in the "complexity" of its political, social, and economic configurations. No doubt then that Levine found Cameroon's stability "most remarkable." Unlike Cameroon, he observed, other African countries federations fractured, including the Central African Federation, Ethiopian-Eritrean Federation, as well as the Federal Republic of Nigeria and the secession of Biafra. In his study on the origins of radical nationalism in Cameroon, Richard A. Joseph (1977) traces the post-World War II birth of the nationalist party, Union of the Population of Cameroon (Union des Populations du Cameroon, UPC), and documents the brutal repression of its militants by the French and their allies in Cameroon who eventually became the leader of the country under Ahmadou Ahidjo at independence. UPC militants were exiled for several years, lured back in the early 1970s, and their leaders were publicly executed.

Judging by recent events, the durability of the Paul Biya regime could continue with his son, Franck Biya, as successor. The French president, Emmanuel Macron, met with him during his recent visit to Cameroon, confirming suspicions that regime supporters are grooming the 50-year-old Franck to succeed his father when the time comes. In 2021, Jeune Afrique had already suggested that his entourage of prominent financiers and entrepreneurs was notable even though Franck had not hinted at any political ambition. Franck Biya, a businessman, currently serves as his father's unofficial adviser but does not hold any political leadership position. Yet, even before the French president's visits, supporters of the regime unfurled Franck's portraits and marched in his support as the potential successor to his father (Jeune Afrique, 2022, 27 july).

The Paul Biya regime's remarkable durability has not drawn many academic interests yet. While there are numerous studies on the durability of autocratic regimes and autocrats' survival in general (Bueno de Mesquita et al., 2003; Gandhi & Przeworski, 2007), we can only identify very few on that of the Paul Biya regime (Ayuk, 2018). Thus, the purpose of this study is not only to fill this gap in the literature but also to address specifically the question of why the majority of Cameroonians are still supporting the Paul Biya regime. In doing so, we adopt a micro-level (or bottom-up) approach by trying to understand the factors that may have led to such support and applying simple statistical analyses and machine learning (or predictive analytics).

Literature Review

For the most part, the contemporary literature on the Cameroonian politics focuses on the dictatorial characteristics of the Paul Biya regime, the division between the Anglophone part (North-West and South-West regions, making up about 20% of the country) and its Francophone part (the rest of the country), which led in recent years to a growing interest in the so-called "Anglophone crisis." In line with this trend, very few studies have been devoted specifically to the durability of the Paul Biya regime, and there is no commonly accepted explanation as to why it has lasted for more than three decades. Nevertheless, the broader literature on the durability of autocratic regimes and the survival of autocrats offers some insights that can help understand the durability of the Paul Biya regime.

Concerning the dictatorial characteristics of the Paul Biya regime, Janvier Tchouteu and others describe and denounce the autocratic rule of Biya in Cameroon in a series of books (Tchouteu, Chouteu-Chando, and Chando, 2017a; Tchouteu, Chouteu-Chando, and Chando, 2017b; Tchouteu, Chouteu-Chando, and Chando, 2018). In each of these books, the authors also accuse France of having designed the Cameroonian political system, having put in power Paul Biya and his predecessor, Ahmadou Ahidjo, and having supported them from independence in 1960 until now. The role of France in designing the Cameroonian political system and "leaving Cameroon in the hands of a government that would be sympathetic to [its] interests" after independence is also pointed out by Martin Atangana (2010). Furthermore, in a recent Foreign Policy article, Jefcoate O'Donnell and Robbie Gramer (2018) describe Biya as "one of the world's most experienced autocrats," who just gave the world "a master class in fake democracy."

With regard to the durability of the Paul Biya regime despite the growing political crisis in the North-West and South-West regions, in one of the few studies on this issue, Augustine Ayuk explains the stability of the Cameroonian political system with the following factors: "a strong ruling party, the Cameroon National Union (CNU), and a strong individual, President Ahmadou Ahidjo" (Ayuk, 2018). From a bottom-up approach and using statistical analyses based on its round 6 national survey on Cameroon, Afrobarometer underlines the fact that, even though most Cameroonians do not approve of the economic policy of the government, they nevertheless think that the president governed well the country in 2014 and they trust him (Afrobarometer, 2015). This would explain why most Cameroonians would vote for him and would not participate in street protests or marches that would overthrow his regime.

Turning to the broader literature on the autocratic regime, we find that several authors identify "the use of political institutions" as one of the major factors that help authoritarian regimes endure and autocrats survive. In line with this, to answer the question of why so-called "good leaders" do not stay in power for long times, while so-called "bad leaders" and dictators manage to do so, Bruce Bueno de Mesquita and others built a "theory on the selection of leaders," and "show how political leaders allocate resources and how institutions for selecting leaders create incentives for leaders to pursue good and bad public policy" (Bueno de Mesquita et al., 2003). In the same vein, Jennifer Gandhi and Adam Przeworski argue that autocratic leaders rely on political institutions, such as legislatures, to "incorporate potential opposition forces, giving them a stake" in regime's survival (Gandhi and Przeworski, 2007). Moreover, Marie-Eve Reny argues that autocratic rulers use the following "four mechanisms to control societal organizations: repression, coercion, cooptation and containment" (Reny, 2019).

Methodology

Using a macro-level (or top-down) approach, The durability of the Paul Biya regime can be explained by what the president and his cronies are doing ( e.g., eliminating any pontential competitors, restraining political rights and civil liberties, etc.). However, if we use a micro-level (or bottom-up) approach, we can also explain it with what the Cameroonians themselves are thinking and doing about it. In other words, we can reasonably think that some Cameroonians may genuinely support the regime or, at least, tolerate its existence to allow it to last for more than three decades. In connection with this, we assume that those who support the regime would also vote for Biya and would not participate in any actions (e.g., street protests) resulting in its termination. Accordingly, we adopt a micro-level (or bottom-up) approach to assess the level of popular support to for the Paul Biya regime and turn to the public opinion polls. Afrobarometer provides us with reliable national surveys that can be used to assess this level of popular support.

Afrobarometer is "a pan-African, non-partisan research network that conducts public attitude surveys on democracy, governance, economic conditions, and related issues in more than 35 countries in Africa" (Afrobarometer, 2019a). Over the years, Afrobarometer's surveys became one of the most trusted and reliable sources of information on African people's opinions and attitudes toward their political and economic conditions, as well as their rulers. Cameroon was included in rounds 5, 6, and 7 of the national surveys conducted by Afrobarometer. Even if the surveys data do not directly address the questions about the durability of the Paul Biya regime, the data allow us to understand the Cameroonian people's opinions and attitudes toward the president and his regime and explain why they are willing to stay under the same regime for so many years.

In this study, we use the approval rating of the job performance of President Biya as a proxy for the level of his popular support and the dependent variable to be explained or predicted. In connection with this, we first assess to what extent the Cameroonian people approve or disapprove Biya's job performance to make his regime durable, analyzing the historical trend and regional variations of their responses, particularly the difference between the French speaking and English speaking communities. Lastly, using machine learning, we use machine learning to identify the factors that may be associated with their approval or disapproval of Biya's job performance. R statistical programming language is used to handle the data manipulation and analysis. We particularly relies on the Caret package in our machine learning procedures (Kuhn, 2019).

Findings

Descriptive Statistics

Afrobarometer's round 7 national survey in Cameroon, which is simply referred to as the "Cameroon round 7 datasets" in this study, consists of responses to 297 questions from 1204 respondents. In selecting these respondents, Afrobarometer used the so-called "national probability samples," which were "designed to meet the following criteria: Samples are designed to generate a sample that is a representative cross-section of all citizens of voting age in a given country. The goal is to give every adult citizen an equal and known chance of being selected for an interview" (Afrobarometer, 2019b). In the case of Cameroon, the following criteria were taken into consideration in selecting respondents: gender, urban or rural locations, level of education, religion, and region (Afrobarometer, 2015).

As mentioned earlier, we focus, in this study, on the "approval of the way the President performed his job" (response question Q58A in Cameroon round 7 dataset) as a proxy for the support for the president and his regime and as a dependent variable (or outcome variable) that may help understand the durability of Paul Biya's regime. In line with this, we assume that the people who approve of the way President Biya performs his job also tend to vote for him and let him stay in power as long as he wishes.

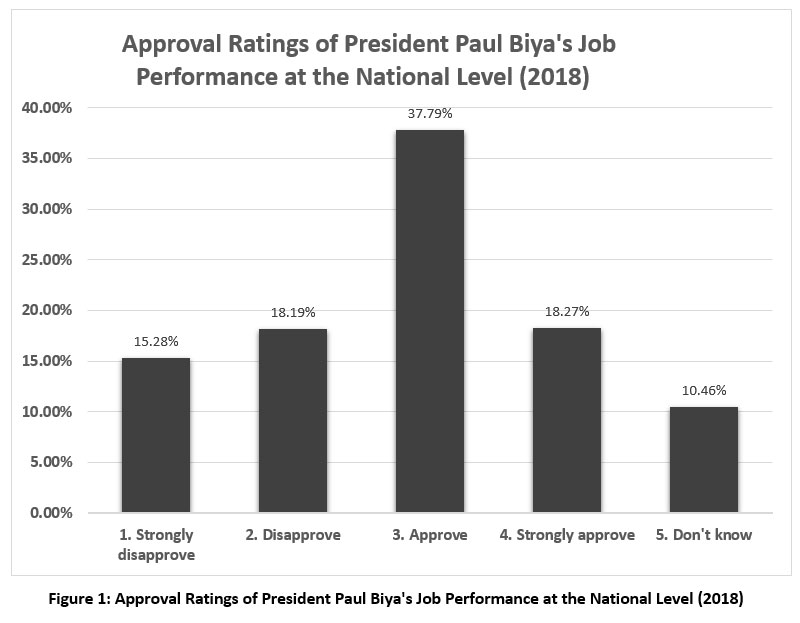

The Cameroon round 7 dataset reveals that the total approval ratings of the presidential job performance in 2018 were 56.06%, with 37.79% of the respondents "approving" and 18.27% "strongly approving.". 1 This is compared to the total disapproval ratings, which were only 33.47%, with 15.28% of the respondents "strongly disapproving" and 18.19% "disapproving."2

Table 1: Approval Ratings of President Paul Biya's Job Performance at the National Level (2018).

|

Approval Scale |

Percentage |

|

1. Strongly disapprove |

15.28% |

|

2. Disapprove |

18.19% |

|

3. Approve |

37.79% |

|

4. Strongly approve |

18.27% |

|

5. Don't know |

10.46% |

|

Figure 1: Approval Ratings of President Paul Biya's Job Performance at the National Level (2018) |

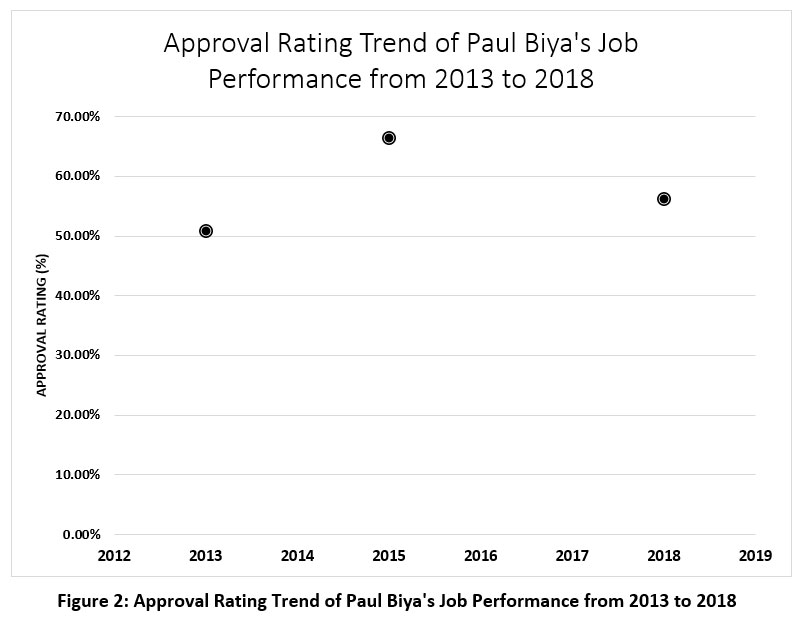

Nevertheless, Biya's approval ratings significantly fluctuated over the years and across the country from 2013 to 2018. As shown in Table 2 and Figure 2., Paul Biya's approval ratings reached their highest levels in 2015, when they were at 66.33%, coming from their lowest levels in 2013, when they were at 50.75%. In other words, despite the major decline between 2015 and 2018, his approval ratings in 2018 were still high compared to those in 2013.3

Table 2: Approval Rating Trend of President Paul Biya's Job Performance at the National Level from 2013 to 2018.

|

2013 |

50.75% |

|

2014 |

|

|

2015 |

66.33% |

|

2016 |

|

|

2017 |

|

|

2018 |

56.06% |

|

Figure 2: Approval Rating Trend of Paul Biya's Job Performance from 2013 to 2018 |

To simplify the interpretation of the approval ratings by region provided by Afrobarometer, we transformed the six levels of approval responses into three categories, combining "strongly disapprove" and "disapprove" as "disapproval," "approve" and "strongly approve" as "approval", and "no answer" and "don't know" as "don't know." Thus, concerning the regional variations of the presidential approval ratings, we find the highest.

approval ratings are located in the South (80%) and in Adamawa (78%); whereas the lowest approval ratings are located in the South West (10%) and in the North West (13%).

Table 3: Approval Ratings of Paul Biya's Job Performance by Region in 2018.

|

Region |

Transformed Approval Rating |

Count |

Percentage |

|

Yaounde |

Approve |

69 |

57% |

|

Disapprove |

36 |

30% |

|

|

Don't know |

17 |

14% |

|

|

Douala |

Approve |

72 |

53% |

|

Disapprove |

48 |

35% |

|

|

Don't know |

16 |

12% |

|

|

Adamawa |

Approve |

50 |

78% |

|

Disapprove |

13 |

20% |

|

|

Don't know |

1 |

2% |

|

|

Center |

Approve |

70 |

67% |

|

Disapprove |

28 |

27% |

|

|

Don't know |

6 |

6% |

|

|

East |

Approve |

30 |

75% |

|

Disapprove |

5 |

12% |

|

|

Don't know |

5 |

12% |

|

|

Extreme-North |

Approve |

162 |

75% |

|

Disapprove |

50 |

23% |

|

|

Don't know |

4 |

2% |

|

|

Littoral |

Approve |

27 |

56% |

|

Disapprove |

17 |

35% |

|

|

Don't know |

4 |

8% |

|

|

North |

Approve |

97 |

71% |

|

Disapprove |

37 |

27% |

|

|

Don't know |

3 |

2% |

|

|

North West |

Approve |

14 |

13% |

|

Disapprove |

62 |

60% |

|

|

Don't know |

28 |

27% |

|

|

West |

Approve |

43 |

41% |

|

Disapprove |

42 |

40% |

|

|

Don't know |

19 |

18% |

|

|

South |

Approve |

32 |

80% |

|

Disapprove |

8 |

20% |

|

|

Don't know |

- |

- |

|

|

South West |

Approve |

9 |

10% |

|

Disapprove |

57 |

64% |

|

|

Don't know |

23 |

26% |

The Predictors (or Determinants) of Paul Biya's Approval Ratings

In this section, we use machine learning (or predictive analytics) to identify the predictors (or determinants) of Biya's approval ratings. In doing so, we follow some of the common steps and procedures suggested by most data analysts using R statistical programming language, particularly, the Caret package (Lantz, 2015; Kuhn, 2019). These steps and procedures include:defining the problem,

- preprocessing the data (if necessary),

- splitting the data into train and test sets,

- selecting features, using the "recursive feature elimination"" or "rfe"" function,

- traning the models on the train set,

- generating variable importance,

- making predictions on the test set and assessing the accuracy of the predictions,4

As noted earlier, to simplify the data analyses and facilitate the interpretation of the findings, we mutate the variable "Q58A", which has six levels into a new variable "approval," which only has three levels, by combining "strongly disapprove" and "disapprove" as"disapproval," "approve" and "strongly approve" as "approval," and "no answer" and "don't know" as "don't know."

Thus, the problem in this machine learning is to predict the "approval" of President Biya's job performance (i.e., the responses to the mutated variable Q58A of the Cameroon Round 7 survey ("Do you approve or disapprove of the way that the President has performed his jobs over the past 12 months?"). In other words, we are dealing here with a machine learning classification into three categories:

- "disapproval" (for those who simply "disapprove" or "strongly disapprove" of the way the president has performed his job),

- "approval" (for those who simply "approve" or "strongly approve" the way the president has performed his job)

- "don't know" (for those who refuse to answer the question or don't know whether to approve or not the way the president has performed his job)

Since we are mainly dealing with categorical variables, except for the "age" of the respondents, which can be left as is (as there is no significant variation in the ages), we do not need to preprocess the data by centering and scaling the variables. Accordingly, we directly proceed to randomize and split the data following the above problem definition. In doing so, we split the dataset into a train set and test set based on the new variable "approval," which is set as the outcome variable (or dependent variable), with a ratio of 75% and 25%.

The first machine learning procedure we run is the feature selection which leads to the computation of the number of variables that would be required to obtain the highest accuracy in the predictions and the identification of the top five variables. The output of the feature selection, using the "recursive feature elimination" (rfe) function in Caret, is as follows:

- 16 variables out of 286 would result in a 73.85% prediction accuracy, and

- The top five variables (out of 16) are:

- Q58B ("Do you approve or disapprove of the way that your member of Parliament has performed her/his jobs over the past 12 months?"),

- Q43A ("How much do you trust the President, or haven't you heard enough about him to say?"),

- Q58C ("Do you approve or disapprove of the way that your elected local government councilor has performed her/his jobs over the past 12 months?"),

- REGION (regional location of the respondent),

- Q99 ("If presidential elections were held tomorrow, which party's candidate would you vote for?").5

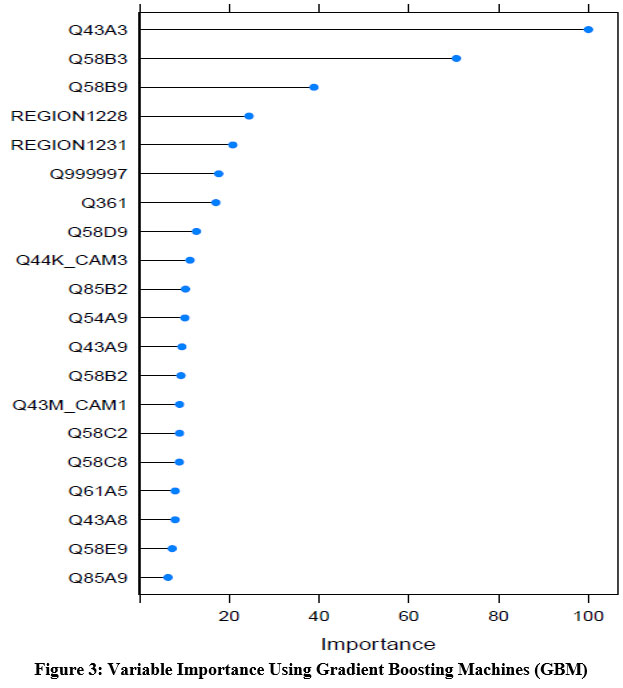

We train two commonly used models (or algorithms) for classification on the training set: Gradient Boosting Machines (GBM) and Random Forest (RF). Since the GBM model generates the highest prediction accuracy of these two models, we focus on the results from this model in this study.

Next, the second procedure we use, following the training of the models, is the "variable importance estimation." Limiting the output of this procedure to the top 20 variables, using the GBM model, we obtain the following variable list along with the importance of each variable:6

These variables correspond to the responses to the following questions:

- Q43A(1 to 9): "How much do you trust the President, or haven't you heard enough about him to say?"

- Q58B(1 to 9): "Do you approve or disapprove of the way that your member of Parliament has performed her/his jobs over the past 12 months?"

- REGION: Regional location of the respondent

- Q99(1220 to 9999): "If presidential elections were held tomorrow, which party's candidate would you vote for?"

- Q36(1 to 9): "Overall, how satisfied are you with the way democracy works in Cameroon?"

- Q58D(1 to 9): "Do you approve or disapprove of the way that your traditional leader has performed her/his jobs over the past 12 months?"

- Q44K_CAM(1 to 9): "How [often] do you think [the customs officers were] involved in corruption, or haven't you heard enough about them to say?"

- Q32(1 to 9): "Do you agree with the following statements? Statement 1: Parliament should ensure that the president explains to it on a regular basis how his government spends taxpayers' money. Statement 2: The president should be able to devote his full attention to developing the country rather than wasting time justifying his actions."

- Q43G3: "How much do you trust the police, or haven't you heard enough about him to say?"

- Q44A(1 to 9): "How [often] do you think [the president was] involved in corruption, or haven't you heard enough about them to say?"

- Q26E(1 to 9): "whether you, personally, have [participated in a demonstration or protest march] during the past year."

- Q24B(0 to 9): "Did you work for a candidate or party [during the last national election in 2013]?"

- Q1: "How old are you?"

- Q42E(1 to 9): "In your opinion, how often, in this country, do officials who commit crimes go unpunished?"

|

Figure 3: Variable Importance Using Gradient Boosting Machines (GBM) |

Finally, in predicting the outcome variable "approval" on the test set, using the trained GBM model, we obtain an accuracy of 73.91 %.

In sum, with relatively high accuracy of 73.91%, we can predict the approval of President Biya's job performance based on the responses of the respondents to questions that have to do mainly with the following factors:

- trust in the president himself,

- approval of the job performance of their member of Parliament,

- regional location of the respondent.

Estimated at 56.06% +/- 3%, Paul Biya's approval ratings remained high on the eve of the 2018 presidential election, despite the political crisis in the Anglophone regions (North-West and South-West), which escalated to a low-level civil war since 2013, despite the Boko Haram's attacks in the Extreme North region, and the relentless attacks by the opposition. According to the opposition and many observers, Biya and his cronies mostly likely committed massive electoral fraud to win this election. Nevertheless, the fact remained that he was still popular among Cameroonians of different regions other than the North-West and South-West. This study aimed to understand this popularity and high approval ratings, which allowed him to stay in power for three decades or more. The implementation of machine learning (or predictive analytics) on the Afrobarometer round 7 survey on Cameroon (cam_round7), using the Caret package along with the GBM and random forest algorithms, allowed us to identify the following factors as the top predictors (with the importance of 20% and higher) of the approval rating of President Paul Biya in 2018:

- approval of the job performances of the members of the Parliament (responses to questions Q58B3 and Q58B9 of cam_round7),

- trust in the president (responses to question Q43A of cam_round7),

- regional location of the respondent (responses to question REGION of cam_round7).

It is worth noting that "satisfaction with democracy" (responses to question Q36 of cam_round7) and "fight against corruption" (responses to question Q44 of cam_round7) figure among the top ten predictors, but their importance is less than 20%, compared to the trust in the president which has an importance of 100%.

In other words, the approval rating of President Paul Biya was not based on his performance in managing the national economy nor in handling the various political problems of the country (such as the crisis in Anglophone regions and the Boko Haram's attacks in the North), but on whether the respondents trusted him, approved the job of the members of the Parliament, or come from regions other than the North-West and the South-West. In this sense, we can explain the durability of the Paul Biya regime based not only on what the regime is doing to repress the opposition, but also on the personal connection or affinity between the Cameroonians and their president and members of the Parliament.

Acknowledgment

None

Funding sources

The authors did not receive any funding or grant from any source in completing this research.

Conflict of Interest

There is no conflict of interest involved in this study.

References

- Acemoglu, D., & Robinson, J. A. (2005). Economic Origins of Dictatorship and Democracy. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

- Afrobarometer. (2015a). Les camerounais n’approuvent pas la politique économique de leur gouvernement mais font confiance à la Police, à l’Armée et au Président de la République [Communiqué de presse]. Retrieved from Afrobarometer website: http://afrobarometer.org/press/les-camerounais-napprouvent-pas-la-politique-economique-de-leur-gouvernement-mais-font

- Afrobarometer. (2015b). Résultats de la sixième enquête AFROBAROMETER au Cameroun. Retrieved June 12, 2019, from http://afrobarometer.org/sites/default/files/media-briefing/cameroon/cam_r6_presentation1_les_institutions_au_Cameroun_16122015.pdf

- Afrobarometer. (2019a). About Afrobarometer. Retrieved March 13, 2019, from http://afrobarometer.org/about

- Afrobarometer. (2019b). Sampling principles and weighting. Retrieved June 12, 2019, from https://www.afrobarometer.org/surveys-and-methods/sampling-principles

- Andersen, J. J., & Aslaksen, S. (2013). Oil and political survival. Journal of Development Economics, 100(1), 89–106. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdeveco.2012.08.008

- Amin, J. A. (2021). President Paul Biya and Cameroon’s Anglophone Crisis: A Catalogue of Miscalculations. Africa Today, 68(1), 95–122. https://doi.org/10.2979/africatoday.68.1.05

- Antwi-Boateng, O. (2015). No Spring in Africa: How Sub-Saharan Africa Has Avoided the Arab Spring Phenomenon. Politics & Policy, 43(5), 754–784. https://doi.org/10.1111/polp.12129

- Anyangwe, C. (2008). Imperialistic Politics in Cameroun: Resistance & the Inception of the Restoration of the Statehood of Southern Cameroons. Bamenda, Cameroon: Langaa RPCIG.

- Argenti, N. (2008). The Intestines of the State: Youth, Violence, and Belated Histories in the Cameroon Grassfields. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

- Asongu, S. A. (2014). A brief clarification to the questionable economics of foreign aid for inclusive human development. Retrieved from African Governance and Development Institute website: http://ssrn.com/abstract=2541220

- Atangana, M. (2010). The End of French Rule in Cameroon. Lanham, MD: University Press Of America.

- Ayuk, A. E. (2018). The Roots of Stability and Instability in Cameroon. In J. Takougang & J. A. Amin (Eds.), Post-Colonial Cameroon: Politics, Economy, and Society (pp. 43–64). Lahman, MD: Lexington Books.

- Babboni, M. (2018). The Revolution Conundrum in Cameroon: A study of Relative Peace Under President Biya's Rule (BA Thesis, Occidental College). Retrieved from https://digitalcollections.sit.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=3856&context=isp_collection

- Bratton, M., & Houessou, R. (2014). Demand for Democracy Is Rising in Africa, But Most Political Leaders Fail to Deliver. Retrieved from Policy Paper #11 website: http://allafrica.com/download/resource/main/main/idatcs/00081403:92cb6c2d9b9a29e9edf3ab0b2a4058b4.pdf

- Bueno de Mesquita, B., Smith, A., Siverson, R. M., & Morrow, J. D. (2003). The Logic of Political Survival. https://doi.org/10.7551/mitpress/4292.001.0001

- Cheeseman, N. (2019). A Divided Continent — BTI 2018 Regional Report Africa. Retrieved from Bertelsmann Stiftung website: https://www.bertelsmann-stiftung.de/doi/10.11586/2019009

- de Vries, L., Englebert, P., & Schomerus, M. (Eds.). (2019). Secessionism in African Politics: Aspiration, Grievance, Performance, Disenchantment. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-90206-7

- Delancey, M. W. (1989). Cameroon: Dependence and Independence. Boulder, CO: Westview Press.

- Edwards III, G. C. (1991). Presidential Approval. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press.

- Edwards III, G. C., Mitchell, W., & Welch, R. (1995). Explaining presidential approval: The significance of issue salience. American Journal of Political Science, 39(1), 108–134.

- Ehteshami, A., Hinnebusch, R., Huuhtanen, H., Raunio, P., Warnaar, M., & Zintl, T. (2013). Authoritarian Resilience and International Linkages in Iran and Syria. In S. Heydemann & R. Leenders (Eds.), Middle East authoritarianisms: Governance, contestation, and regime resilience in Syria and Iran (p. 222). Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

- Evans, P. B. (1995). Embedded Autonomy. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- FitchSolutions. (2019). Cameroon: Country Risk Report, Includes 10-year forecasts to 2028 (Cameroon Country Risk No. Q2 2019). London, UK: Fitch Solutions Group Limited.

- Fossungu, P. A.-A. (2013). Understanding Confusion in Africa: The Politics of Multiculturalism and Nation-building in Cameroon. Bamenda, Cameroon: Langaa RPCIG.

- Fowler, I., & Zeitlyn, D. (1996). African Crossroads: intersections between history and anthropology in Cameroon. Providence, RI: Berghahn Books.

- France 24. (2022, July 26). Replay: Macron's West Africa Tour: French, Cameroonian Presidents Hold Press Conference. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QVkuSa8GCCA

- Gandhi, J. (2008). Political Institutions under Dictatorship. New York, New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Gandhi, J., & Przeworski, A. (2006). Cooperation, cooptation, and rebellion under dictatorships. Economics & Politics, 18(1), 1–26.

- Gandhi, J., & Przeworski, A. (2007). Authoritarian institutions and the survival of autocrats. Comparative Political Studies, 40(11), 1279–1301.

- Glickman, H. (Ed.). (1995). Ethnic conflict and democratization in Africa. Atlanta, GA: African Studies Association Press.

- Hegre, H., Allansson, M., Basedau, M., Colaresi, M., Croicu, M., Fjelde, H., … Vestby, J. (2019). ViEWS: A political violence early-warning system. Journal of Peace Research, 56(2), 002234331982386. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022343319823860

- Heydemann, S., & Leenders, R. (Eds.). (2013). Middle East authoritarianisms: governance, contestation, and regime resilience in Syria and Iran. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

- Hildebrandt, T. (2015). Social Organizations and the Authoritarian State in China (Reprint edition). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Hinshaw, D., & Parkinson, J. (2018, November 4). Can't Find Cameroon's President? Try Geneva's Intercontinental Hotel. Wall Street Journal. Retrieved from https://www.wsj.com/articles/where-does-the-lion-sleep-tonight-genevas-intercontinental-hotel-1541368940

- Ihonvbere, J. O., & Mbaku, J. M. (Eds.). (2003). Political Liberalization and Democratization in Africa: Lessions from Country Experiences. Retrieved from http://books.google.com/books?id=5FG0Y5DFptUC

- Isbell, T. (2017). Perceived patronage: Do secret societies, ethnicity, region boost careers in Cameroon? (Dispatches No. 162). Retrieved from Afrobarometer website: http://afrobarometer.org/publications/ad162-perceived-patronage-do-secret-societies-ethnicity-region-boost-careers-cameroon

- Ishak, P. W. (2019). Autocratic Survival Strategies: Does Oil Make a Difference? Peace Economics, Peace Science and Public Policy, 0(0). https://doi.org/10.1515/peps-2018-0043

- Jeune Afrique. (2022, 27 juillet). Cameroun: tête-à-tête avec Biya, Rencontre avec son fils Franck… Les coulisses de la visite de Macron. JeuneAfrique.com. https://www.jeuneafrique.com/1365118/politique/cameroun-tete-a-tete-avec-biya-rencontre-avec-son-fils-franck-les-coulisses-de-la-visite-de-macron/

- Joseph, R. (1977). Radical Nationalism in Cameroun: Social Origins of the UPC Rebellion.

- Jules Roger, S. E. (2018). Inside the Virtual Ambazonia: Separatism, Hate Speech, Disinformation and Diaspora in the Cameroonian Anglophone Crisis (MA Thesis, University of San Francisco). Retrieved from https://repository.usfca.edu/thes/1158

- Kamé, B. P. (2018). The Anglophone Crisis in Cameroon. Paris, France: L’Harmattan.

- Kaushik, S. (2016, December 8). Practical guide to implement machine learning with CARET in R. Retrieved April 18, 2019, from Analytics Vidhya website: https://www.analyticsvidhya.com/blog/2016/12/practical-guide-to-implement-machine-learning-with-caret-package-in-r-with-practice-problem/

- Kieh, Jr., George K., & Agbese, P. O. (Eds.). (2013). Reconstructing the Authoritarian State in Africa. Retrieved from http://books.google.com/books?id=wQMiAQAAQBAJ

- Konings, P., & Nyamnjoh, F. B. (2003). Negotiating an Anglophone identity: A study of the politics of recognition and representation in Cameroon. Leiden and Boston: Brill.

- Kuhn, M. (2019). The caret Package. https://topepo.github.io/caret/index.html

- Krieger, M. (2008). Cameroon's Social Democratic Front: Its History and Prospects as an Opposition Political Party. Mankon, Bamenda: Langaa RPCIG.

- Lantz, B. (2015). Machine Learning with R (2 edition). Birmingham, UK: Packt Publishing.

- Lazar, M. (2019). Cameroon's linguistic divide deepens to rift on questions of democracy, trust, national identity (Dispatches No. 283). Retrieved from Afrobarometer website: http://afrobarometer.org/sites/default/files/publications/Dispatches/ab_r7_dispatchno283_ anglo_francophone_divisions_deepen_in_cameroon.pdf

- Le Vine, V. T. (1971). Cameroon Federal Republic. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

- Letsa, N. (2018, November 8). What's Driving the Conflict in Cameroon? Foreign Affairs. Retrieved from https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/cameroon/2018-11-08/whats-driving-conflict-cameroon

- Levitsky, S. R., & Way, L. A. (2012). Beyond patronage: Violent struggle, ruling party cohesion, and authoritarian durability. Perspectives on Politics, 10(4), 869–889.

- Levitsky, S., & Way, L. A. (2010). Competitive authoritarianism: Hybrid regimes after the cold war. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

- Linz, J. J. (2000). Totalitarian and Authoritarian Regimes. Boulder, CO: Lynne Rienner Publishers.

- Mawere, M., & Mwanaka, T. R. (Eds.). (2015). Democracy, Good Governance and Development in Africa. Retrieved from https://books.google.com/books?id=IO3pCgAAQBAJ

- Mbah, E. (2016). Environment and Identity Politics in Colonial Africa: Fulani Migrations and Land Conflict. New York, NY: Routledge.

- Mbaku, John M., I, F. A., Ngwafu, P., Nkwi, W. G., Ndille, R. N., Mimche, H., … Nnanga, R. M. (2018). Post-Colonial Cameroon: Politics, Economy, and Society (J. Takougang & J. A. Amin, Eds.). Lanham, MD: Lexington Books.

- Mbaku, John Mukum, & Takougang, J. (Eds.). (2003). The Leadership Challenge in Africa: Cameroon Under Paul Biya. Trenton, NJ: Africa World Pr.

- Mboma, A. (2017). Cameroon Politics and Governance: Cameroon Environmental Study, History Evaluation, and First World War, Education, Corruption. Scotts Valley, CA: CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform.

- Mbu, J. (2006). Civil Disobedience in Cameroon. New York: iUniverse, Inc.

- Mentan, T. (2013). Democracy for Breakfast. Unveiling Mirage Democracy in Contemporary Africa. Retrieved from http://books.google.com/books?id=Kt4WAgAAQBAJ

- Moritz, M. (2010). Understanding Herder-Farmer Conflicts in West Africa: Outline of a Processual Approach. Human Organization, 69(2), 138–148. https://doi.org/10.17730/humo.69.2.aq85k02453w83363

- Mukete, Victor. E. (2013). My Odyssey: The Story of Cameroon Reunification. Yaounde, Cameroon: Eagle Publishing.

- Muvunyi, F. (2018, November 1). Cameroon is melting down — and the United States couldn't care less. Washington Post. Retrieved from https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/democracy-post/wp/2018/11/01/cameroon-is-melting-down-and-the-united-states-couldnt-care-less/

- Nganji, J. T., & Cockburn, L. (2019a). Use of Twitter in the Cameroon Anglophone crisis. Behaviour & Information Technology, 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1080/0144929X.2019.1620333

- Nganji, J. T., & Cockburn, L. (2019b, June 18). How Twitter has been used in Cameroon's Anglophone crisis. The Conversation. Retrieved from http://theconversation.com/how-twitter-has-been-used-in-cameroons-anglophone-crisis-118272

- Nhemachena, Artwell, & Mawere, Munyaradzi. (2017). Africa at the Crossroads: Theorising Fundamentalisms in the 21st Century. Bamenda, Cameroon: LANGAA RPCIG.

- Njoh, M. G. (2006). The political regimes of Ahmadou Ahidjo and Paul Biya, and Christian Tumi, Priest. Douala, Cameroon: Christian Cardinal TUMI.

- O'Donnell, J., & Gramer, R. (2018, October 22). Cameroon's Paul Biya Gives a Master Class in Fake Democracy. Foreign Policy. Retrieved from https://foreignpolicy.com/2018/10/22/cameroons-paul-biya-gives-a-master-class-in-fake-democracy/

- O'Grady, S. (2019, February 5). Divided by Language. Washington Post. Retrieved from https://www.washingtonpost.com/graphics/2019/world/cameroon-anglophone-crisis/

- Reny, M.-E. (2019). Autocracies and the Control of Societal Organizations. Government and Opposition, 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1017/gov.2019.7

- Rudbeck, J., Mukherjee, E., & Nelson, K. (2016). When autocratic regimes are cheap and play dirty: the transaction costs of repression in South Africa, Kenya, and Egypt. Comparative Politics, 48(2), 147–166.

- Schedler, A. (Ed.). (2006). Electoral Authoritarianism: The Dynamics of Unfree Competition. Boulder, CO: Lynne Rienner Publishers.

- Searcey, D. (2018, October 7). Cameroon on Brink of Civil War as English Speakers Recount 'Unbearable' Horrors. The New York Times. Retrieved from https://www.nytimes.com/2018/10/06/world/africa/cameroon-election-biya-ambazonia.html

- Svolik, M. W. (2012). The Politics of Authoritarian Rule. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- Takougang, J. (1998). Democracy and Democratization in Cameroon: Living with the Dual Heritage (Vol. 208). Aldershot, England: Ashgate.

- Tchouteu, J., Chouteu-Chando, J., & Chando, J. T. (2017a). Cameroon: France's Dysfunctional Puppet System in Africa. New York, NY: TISI Books.

- Tchouteu, J., Chouteu-Chando, J., & Chando, J. T. (2017b). Cameroon: The Haunted Heart of Africa. Independently published.

- Tchouteu, J., Chouteu-Chando, J., & Chando, J. T. (2018). Paul Biya of Cameroon: Three-Plus Decades of Misrule Under an Anachronistic French-Imposed System. New York, NY: TISI Books.

- Terretta, M. (2013). Nation of Outlaws, State of Violence: Nationalism, Grassfields Tradition, and State Building in Cameroon (1 edition). Athens, Ohio: Ohio University Press.

- The Economist. (2018, May 31). Repression is worsening in Cameroon amid an uprising over language. The Economist. Retrieved from https://www.economist.com/middle-east-and-africa/2018/06/02/repression-is-worsening-in-cameroon-amid-an-uprising-over-language

- Ugbudian, L. I. (2018). The Role of Natural Resources in Nigeria-Cameroun Border Dispute. Global Journal of Human-Social Science Research, 18(5), 8–16.

- Vine, V. T. L., Ngenge, T. S., Jua, N., Mentan, T., Vidacs, B., Nyamnjoh, F., & Fokwang, J. (2003). Cameroon: Politics and Society in Critical Perspectives (262 edition; J.-G. Gros, Ed.). Lanham, Md: University Press Of America.

- Wikipedia contributors. (2018). Cameroon. In Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. Retrieved from https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Cameroon&oldid=853236858

- Wikipedia contributors. (2019). United States presidential approval rating. In Wikipedia. Retrieved from https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=United_States_presidential_approval_rating&oldid=900325469

- Wintrobe, R. (2000). Political Economy of Dictatorship. Cambridge, U.K.: Cambridge University Press.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.