Is Task-Based Instruction Apt for Ethiopian Journalism Education?

Shafaat Hussain 1  and Sadaquat Hussain 2

and Sadaquat Hussain 2

1Journalism and Communication, Madda Walabu University, Ethiopia .

2Encyclomedia Communication and Entertainment, Hyderabad, Telangana, India .

DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.12944/CRJSSH.1.2.03

Copy the following to cite this article:

Hussain S. 2018"Is Task-Based Instruction Apt for Ethiopian Journalism Education"? Current Research Journal of Social Sciences and Humanities 1(2). DOI:http://dx.doi.org/10.12944/CRJSSH.1.2.03

Copy the following to cite this URL:

Hussain S. 2018"Is Task-Based Instruction Apt for Ethiopian Journalism Education"? Current Research Journal of Social Sciences and Humanities 1(2).Available From: https://bit.ly/2Fj5dAZ

Download article (pdf) Citation Manager Review / Publish History

Select type of program for download

| Endnote EndNote format (Mac & Win) | |

| Reference Manager Ris format (Win only) | |

| Procite Ris format (Win only) | |

| Medlars Format | |

| RefWorks Format RefWorks format (Mac & Win) | |

| BibTex Format BibTex format (Mac & Win) |

Article Review / Publishing History

| Received: | 31-07-2018 | |

|---|---|---|

| Accepted: | 13-11-2018 | |

| Plagiarism Check: | Yes | |

| Reviewed by: | Dr. Pallav Vishnu | |

| Second Review by: | Dr. Asif Nawaz | |

| Final Approval by: | Dr. Adnan Yousef Atoum | |

Ethiopian University undergraduates lack in English language skills and content competence is a usual discussion among instructors, educationists and industrialists.1, 2, 3, 4 This issue which is not only an issue of Ethiopia, has been attempted to address in different multilingual parts of the world through different approaches of teaching and learning. This study presents an obvious rationale for why TBI should be adopted as an approach at Journalism and Communication undergraduate pedagogy in the Ethiopian context. Foremost, University entrants, in general, are linguistically weak to follow instructions in English that affect their grade achievement and therefore they lack in motivation, interest, involvement, enthusiasm and curiosity. The emphasis over language skill development through TBI would make their learning better, easier and faster. Third, employers always complain that Universities are not producing competent and state-of the-art journalists. The emphasis over innovative pedagogy, procedural activities, tasks and assessments in the classroom through TBI can bring change (in fluency, vocabulary, pronunciation) because learning is maximum if learners use language with the content involvement. Finally, exposure to FL outside the classroom is scarce in Ethiopian context which justifies the need of linguistic scaffolding to the Journalism undergrads. Therefore, the teaching of journalism in Ethiopia is unique in the sense that both teachers and students are struggling with this serious problem as the former has to teach content with learner’s poor EFL skills and competences and the latter has to struggle for academic achievement with their poor EFL skills and subject competence.2

The concept of ‘task’ has emerged as a vital component in syllabus design for journalism education. The literature review mirrors that the perception of the task is somewhat vague; however, various endeavours have been made to define it. There is convincing evidence in the history of language teaching that there is no agreement about the definition of a "task", and its description is a bit controversial. "Task" varies from other expressions such as "activity", or "exercise" or "drill" which have overwhelmingly controlled our classes to teach students language and to expedite the process of learning. Nunan (1989) explicates that a ‘task’ is a slice of classroom work which engages learners in understanding, handling, producing, or interacting in the target language.5 The centre of attention is principally focused on meaning rather than form. Skehan (1996) defines the task as "an action in which meaning is the most important; there is some sort of association to the actual world; task accomplishment has some priority, and the evaluation of task performance is in terms of task result".6 According to Khatib, Rezai, & Derekshan (2011), task is described as a slice of language that linguistically, substantially, emotionally, rationally, socially, analytically, implicitly, innovatively, intentionally or unintentionally, artistically, extemporaneously, motivationally, and experientially includes learners in the progression of learning.7 Theoretically, task is used in three ways – as one component of a course, as a technique and as a syllabus design. Conceptually, there are two types of tasks – pedagogical tasks and target tasks. Pedagogical tasks are those that take place in the classroom as a trial for real-world assignments. For example, a role play in which learners practice for a job interview would be a task of this type. The target tasks refer to usages of language beyond the classroom.

Task-Based Syllabus

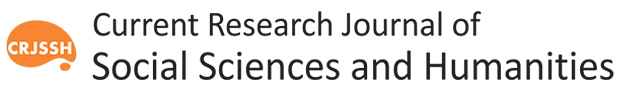

Before digging the concept of task-based syllabus design (TBSD), it is important to clear the confusion between the two terms -- ‘curriculum’ and ‘syllabus’. ‘Curriculum’ is the systematic description of the plan, implementation, evaluation, management and administration of an academic institution focusing over educational goals and their attainments whereas, ‘syllabus’ is selection and grading of the content plus associated activities in a program of study (Nunan 1989). Syllabus design has been a fragmented concept. It is concerned with ‘what’ of a language program (content) and ‘how’ of a language program (methodology). Syllabus design refers to the arrangement of the elements of the teaching and learning process for a program of study by an academic institution.8 TBSD advocates that language learning results from crafting the right types of interactional procedures in the classroom, and the best technique to create these is to practice especially aimed instructional tasks. The TBSD guides the teacher what kinds of tasks and activities will be undertaken in class each day. The syllabus, therefore, offers a framework for classroom activity, gratifying the title role of ‘syllabus as plan’. This syllabus has no linguistic specifications but ‘instead contained a series of tasks in the form of problem-solving activities’. Interaction is considered as a facilitator of acquisition of the foreign language. Grammar construction can occur through an emphasis on meaning only.

|

Figure 1: Reflected from |

The TBSD was the outcome of two short-lived projects – Malaysian Project (1975) and Bangalore Project (1983). They founded a new dimension in Second Language Pedagogy which was a conscious attempt to compare different methodological approaches to the teaching of English.

|

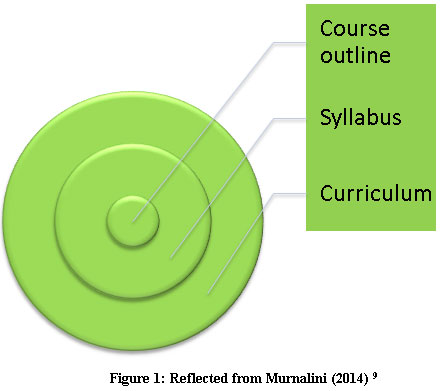

Figure 2: Origin of TBSD Adapted from Nunan (2009) Click here to view figure |

In a seminal publication in 1976, Wilkins suggested that every syllabus can be fitted into two approaches of syllabus design –synthetic and analytical. The synthetic approach of syllabus design proposes a philosophical view of learning wherein diverse components of language are taught independently and stage by stage for acquisition. In the analytical approach of syllabus design whole language is presented at a time to the learner and the learner breaks it down into parts. David Kolb (1984) is known as the advocators of a third approach which is known as ‘experiential approach’ of language syllabus design. TBSD is the outcome of the experiential approach to syllabus design. The experiential approach provides a philosophical view of learning wherein language is learned through learner’s experience and his task engagement: learning by doing. This is more student-centred, more student-autonomous which make them in charge of their own learning. This is the reason that many SLA researchers proved that engaging learners in tasks provide a better context for the activation of the cognition process and better prospects for language learning to occur. Tasks give learners a platform to negotiate to mean and engage them in naturalistic communication.10

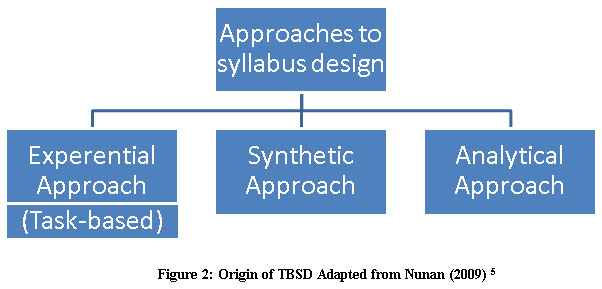

It is generally agreed among the scholars that there are four building blocks of any syllabus design and they are – aims/objectives, contents/subject matters, procedures/activities and finally the evaluations/assessments.8 Therefore, I would base my arguments of TBI on these four components and will attempt to examine how far it is consistent with the current demands of the teaching-learning process.

|

Figure 3: Framework of syllabus design conceived from Arulsamy (2012) 8 |

Objectives in TBSD

The aim of TBSD is to increase the students’ capacity for communication rather their declarative knowledge about the target language, although the teacher would be expected to ensure that sufficient breadth of language content was included in the course.

The general objectives achieved through TBSD are to:

- learning language through expression

- learning language as an object of learning

- learning language as a medium of relationship and conduct

- learning language as remedial learning based on error analysis

The specific objectives achieved through TBSD as Richards & Rodgers (2001) highlights are to:

- communicate accurately and effectively with the help of tasks and activities

- identify the various real world situations of English language use

- learning language as per the communicative need of the target learner

- learning language as per the proficiency level of the target learner

- learning language as per the available resources of the target learner

- learning language as per the path and pace of the target learner.11

Contents in TBSD

The subject matters in the syllabi are selected and graded through guidelines on the principle of ‘higher the level greater the task’. The content is negotiated between teachers and learners. The selection of the content of a course is built upon social and problem-solving interaction. The contents of TBSD are based on the principles as under:

- A need-based approach to content selection

- Learning to communicate through interaction in the target language

- Use of genuine text

- Focus on the learning process; not only on language

- Learner’s experience; a tool of classroom learning

- Linking classroom language use to outside

Procedures in TBSD

The activities under TBSD are ‘reasoning-gap activities’, which involve originating some new information from given facts through processes of inference, deduction, practical reasoning, or a view of relationships or designs.12 Role-playing, pair work, simulation, characterization and dramatization are the other activities that may be practised in the language classroom through TBSD. Group-work is allowed in the classroom, but not actively encouraged. In TBSD the role of teachers is as follows:

- Selector and sequencer of tasks

- Pre-task preparatory/cuing

- Employer of form-focusing linguistic inputs into the tasks and activities

In TBSD the role of learners are as under:

- Group participants because pair and group work is common in TBSD activities.

- Self-monitored because they notice how language is used through tasks

- Risk taker and innovator because many times during the task accomplishment, the learner has a crisis of linguistic input and prior experience.

It will depend on the task designer what kinds of teaching materials would be needed in the classroom. Some of the best available examples are as under:

- Exercise handbooks

- Cue-cards

- Activity cards

- Pair practice materials

- Practice workbooks

- Realia (authentic and real life materials)

- Different media

- Maps/pictures/graphs/charts/diagrams

Table 1: Use of media in TBSD

|

S. No. |

Media |

Tasks |

|

1 |

Newspaper |

Learners prepare an ad for vacancy positions using classifieds. |

|

2 |

Television |

Watching an ad from television and trying to make a new one. |

|

3 |

Internet |

Using three search engines, trying to compare which is best. |

Evaluation In TBI

Evaluation is one of the important components of any syllabus design. Whether objectives of a syllabus design is achieved or not; how far the program is effective; and how about the performance of the learner, is realized through the evaluation process. The natures of evaluation in TBSD are:

- Formative (stage-wise monitoring learners’ progress throughout the learning process).

- Criterion-referenced (learning outcome irrespective of the group).

- Direct assessment (the learners are required to reproduce the real world communication through testing).

- Objective referenced rather than proficiency oriented

The tools and techniques of evaluation in TBI listed by Nunan (2004) are as under:

- Observation

- Teacher-constructed classroom tests

- Students self-assessment procedure

- Performance scales

- Teacher/learner journal

- Oral proficiency rating

- Portfolios

- Production tasks (role plays, simulations, discussions).5

The criteria for assessing learner performance are as follows:

- Accuracy – complexity – fluency

- Course objective

Advantages of TBI

Some of the key advantages of TBI are the following:

- TBI gives the learner a platform to negotiate to mean with the help of experiential inputs and engage learners in naturalistic communication.

- It better activates the cognition process of language learning. Tasks work as catalysts for language learning.

- TBI is something that students accomplish using their existing language resources.

- It is not directly linked to learning the language of teaching and learning, though language acquisition occurs as the student carries out the task.

- TBI focuses on meaning. If the task involves two or more learners, it calls upon the learners’ use of communication stratagems and interactional expertise.

Criticism of TBI

- TBI seems very vague as a methodology to be commonly embraced. The model lacks in clear cut psycholinguistic foundation that makes it difficult to assess according to current models of language acquisition. The task-based approach doesn’t address specific language acquisition issues.13

- Task-based curriculum tells the instructor what types of accomplishments will be carried out in the classroom but not what language items should be prescribed. No overt provision is made for an emphasis on language form.13

- Criteria for choosing and sequencing tasks are highly problematic work. Even if the criteria are well defined, the problem is it's successful outlining.

- TBSD focuses more on classroom procedures rather than learning outcomes. Evaluation is a challenging process in TBSD.

- The syllabus design goes smoothly at primary level but it is difficult to design for a higher level.

- Fluency at the cost of accuracy, which comes into the framework of TBSD, is not agreed by many scholars.

- It requires highly competent teachers.

- It also requires self-aware students in order to be successful

It banks on a large number of instructional materials.

Conclusion

TBSD is full of challenges in all areas of syllabus design. Despite its link to CLT methodology and association with some second language theorists, TBSD has gained considerable attention despite the fact that it has little documentation concerning its implication as a basis for planning and instruction in language teaching. Furthermore, several dimensions of TBSD have yet to be explored, for instance, task sequencing and assessment of task enactment. TBSD has more potential than other syllabi designs if it completely comes out from the domain of ideology to the terrain of reality. The nature of teaching journalism and communication can be contextualized to the task-based curriculum, course material, and classroom procedure. The modern literature argues about the practical focused approach of journalism education. In so doing TBI approach and philosophy can be used for curriculum development, material design, and classroom procedure of journalism education. This will certainly improve the learners’ academic and professional competence. More studies are needed to empirically check the contextualization of TBI and Journalism

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank Madda Walabu University, Ethiopia and Encyclomedia, Hyderabad, India in facilitating to write this research article.

Conflict of Interest

There is no conflict of interest for this article

Funding Source

No grant is provided for this article.

References

- Lakachew M. Teachers Attitude towards CLT and Practical Problems in its Implementation (Master’s dissertation). Addis Ababa, Addis Ababa University. 2003

- Hussain S. Contextualizing CLIL to Journalism Undergraduate Pedagogy: A Call for Discourse-oriented Curriculum, Material and Classroom (Masters dissertation). Bale-Robe, Madda Walabu University. 2016

- Yemene D. English Teachers’ Perception and Practice of CLT in the Teachings of English as a Foreign Language (Master’s dissertation). Addis Ababa, Addis Ababa University. 2007

- Yonas A. Primary School Teachers’ Perceived Difficulties in Implementing Innovative ELT Methodologies in Ethiopian Context. IER Flambeau. 2003;11(1):23-55.

- Nunan D. Designing Tasks for the Communicative Classroom. Cambridge, Cambridge University Press. 1989.

- Skehan P. A Framework for the Implementation of Task-based Instruction. Applied Linguistics. 1996;17(1):38-62.

CrossRef - Khatib M., Rezaei S., Derakhshan A. A Task-Based Approach to Teaching Literature. International Journal of English Linguistics. 2011;1(1):213-218.

CrossRef - Arulsamy S. Curriculum Development. New Delhi: Educational Publishers. 2012.

- Murnalini T. Curriculum Development. New Delhi, Neelkamal Publication. 2014.

- Kolb D. Experiential Learning: Experience as the Source of Learning and Development, New Jersey, Prentice Hall. 1984

- Richards J. C., Rodgers T. S. Approaches and Methods in Language Teaching, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press. 2001.

CrossRef - Prabhu, N. (1987). Second Language Pedagogy. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Long, M., & Crooks, G. (1991). Three Approaches to Task-based Design, TESOL Quarterly, 26 (1), 27-55.

CrossRef

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.