‘In a sense, the Court created the present-day Community; it declared the Treaty of Rome to be not just a treaty but a constitutional instrument that obliged individual citizens and national government officials to abide by those provisions that were enforceable through their normal judicial processes.’

Shapiro (1992, p. 123)

Abstract

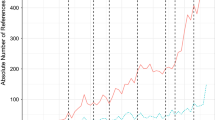

The European Court of Justice (ECJ) is a very powerful court compared to other international courts and even national courts of last resort. Observers almost unanimously agree that it is the preliminary references procedure that made the ECJ the powerful court it is today. In this article, we analyze the factors that lead national courts to use the procedure. We add to previous studies by constructing a comprehensive panel dataset (1982–2008) and identify the economic structure, familiarity with EU law, and tenure of democracy as new determinants.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

The constitutional change was ‘implicit’ in the sense that it occurred although the European Treaties—the equivalent of the European Constitution—were not explicitly modified. The concept of implicit constitutional choice is more explicitly described in Voigt 1999.

It might be noteworthy that the German Federal Constitutional Court invoked its first preliminary reference procedure ever only in 2014. In the case, the Court had to decide about the constitutionality of the newly established European Stabilization Mechanism.

On the other hand, it is well known from trade theory that the trade to GDP ratio tends to be higher in smaller states as large countries can be more self-sufficient. If this was true, requests for preliminary references might be brought forward more frequently by small, rather than large, states.

A well-known case is Manninen (2004), in which the ECJ held that any tax imputation system that only imputes corporate taxes on dividends from locally resident companies violates the EU Treaty.

Monist orders need a way to deal with potential conflicts between domestic and international law. Hence, there are actually two kinds of monism: one in which international law enjoys precedence over national law and one in which domestic law enjoys precedence over international law. After the ECJ’s Van Gend en Loos decision, however, this distinction is superfluous within the EU. Further, EU law is different from international law since it determines by which procedure it is to be implemented into national legislation. This does not, however, exclude the possibility that different traditions of how to implement international law into national legislation can affect the propensity of nation state judges to refer a case to the ECJ.

Following Harutyanyan and Mavcic (1999), these EU member states are coded 0, i.e. as not adhering to the Austrian model of judicial review: Denmark, Estonia, France, Greece, Portugal and Sweden.

A referee of this journal pointed out that although top level courts are legally obliged to ask the ECJ for preliminary references under specific circumstances, they still enjoy considerable discretion in their decision. Their incentive to call on the ECJ should be considerably lower than those of lower courts, since they are unlikely to gain any influence by invoking the preliminary reference procedure. The expected sign of the coefficient would, hence, be somewhat ambiguous.

Alternatively, we could have counted the number of law firms with first-rate competence in European law, but that would have been a much more subjective measure.

We use the average of the spring and autumn wave of the Eurobarometer (1982–2008) question QA6: ‘Generally speaking, do you think that your country’s membership of the European Union is …? A good thing/A bad thing.’

The Poisson estimator relies on the more restrictive assumption that the variance must equal the mean. Only if this condition is met, the model might do a better job of canceling out the country-fixed effects.

References

Allison, P. D., & Waterman, R. P. (2002). Fixed effects negative binomial regression models. In M. Stoltenberg (Ed.), Sociological methodology (pp. 247–265). Oxford: Basil Blackwell.

Alter, K. (1996). The European Court’s political power. West European Politics, 19, 458–487.

Carrubba, C., & Murrah, L. (2005). Legal integration and the use of the preliminary ruling process in the European Union. International Organization, 59, 399–418.

CEPEJ (European Commission for the Efficiency of Justice). (2010). European judicial systems: Efficiency and quality of justice. https://wcd.coe.int.

Elkins, Z., Ginsburg, T., & Melton, J. (2009). The endurance of national constitutions. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

EuGH. (2009). Jahresbericht. http://curia.europa.eu.

Fiorina, M. (1982). Legislative choice of regulatory forms: Legal process or administrative process. Public Choice, 38, 33–66.

Guimarães, P. (2008). The fixed effects negative binomial model revisited. Economics Letters, 99, 63–66.

Harutyanyan, G., & Mavcic, A. (1999). Constitutional review and its development in the modern world. Ljbubljana: Yerevan.

Hausman, J., Hall, B. H., & Griliches, Z. (1984). Econometric models for count data with an application to the patent-R&D relationship. Econometrica, 52, 909–938.

Hofstede, G. (1997). Cultures and organizations—Intercultural cooperation and its importance for survival. London: Profile Books.

La Porta, R., Lopez-de-Silanes, F., & Shleifer, A. (2008). The economic consequences of legal origins. Journal of Economic Literature, 46, 285–332.

La Porta, R., Lopez-de-Silanes, F., Shleifer, A., & Vishny, R. (1997). Legal determinants of external finance. Journal of Finance, 52, 1131–1150.

Mattli, W., & Slaughter, A.-M. (1998). Revisiting the European Court of Justice. International Organization, 52, 177–209.

Nugent, N. (1999). The government and politics of the European Union. Houndsmills: Macmillan.

Paxton, P. (2002). Social capital and democracy: An interdependent relationship. American Sociological Review, 67, 254–277.

Pitarakis, J.-Y., & Tridimas, G. (2003). Joint dynamics of legal and economic integration in the European Union. European Journal of Law and Economics, 16, 357–368.

Putnam, R. (1993). Making democracy work. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Shapiro, M. (1992). The European Court of Justice. In A. Sbragia (Ed.), Europolitics—Institutions and policymaking in the “New” European community (pp. 123–156). Washington, DC: Brookings Institution.

Stone Sweet, A., & Brunell, T. (1998a). The European court and the national courts: A statistical analysis of preliminary references, 1961–1995. Journal of European Public Policy, 5, 66–97.

Stone Sweet, A., & Brunell, T. (1998b). Constructing a supranational constitution: Dispute resolution and governance in the European community. American Political Science Review, 92, 63–81.

Tridimas, G., & Tridimas, T. (2004). National courts and the European Court of Justice: A public choice analysis of the preliminary reference procedure. International Review of Law and Economics, 24, 125–145.

Vink, M., Claes, M., & Arnold, C. (2009). Explaining the use of preliminary references by domestic courts in EU member states: A mixed-method comparative analysis. Paper presented at the 11th Biennial Conference of the European Union Studies Association.

Voigt, S. (1999). Implicit constitutional change—Changing the meaning of the constitution without changing the text of the document. European Journal of Law and Economics, 7, 197–224.

Voigt, S. (2010). The interplay between National and International Law—Its economic effects drawing on four new indicators. http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=925796.

Voigt, S. (2012). On the optimal number of courts. International Review of Law and Economics, 32(1), 49–62.

Zweigert, K., & Kötz, H. (1998). An introduction to comparative law. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Andreas Engert, Christoph Engel, Paulo Guimarães, Mariusz Goleckifor, Gerhard Wagner, Daniel Zimmer, two anonymous referees as well as the editors of this journal for helpful comments and suggestions. We would like to thank the European Association of Law & Economics (Hamburg 2011), the German Association of Law & Economics (Bonn 2011) and the American Law and Economic Association (Stanford 2012) participants.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix: List of variables

Appendix: List of variables

Agriculture |

The agricultural value added as a share of GDP; source: World Development Indicators (WDI) |

Catholic |

Percentage of a country’s population professing the Catholic religion in 1980 (younger states are counted based on their average from 1990 to 1995); sources: PT and BMVW |

Chalstag |

The stage of the legislative process at which a bill can be reviewed for constitutionality: (1) pre-promulgation, (2) post-promulgation, (3) either pre or post, (0) no time explicitly specified; source: Elkins et al. (2009) Comparative Constitutions Project |

Corporate tax rate |

Tax rate for the basic central government statutory (flat or top marginal) corporate income tax (including surtax if applicable); source: OECD tax database and KPMG Corporate and Indirect Tax Rate Surveys |

Democratic age |

Age of democracy defined as (2000 − AGE)/200, with values varying between 0 and 1, where AGE is the first year of democratic rule in a country that continues uninterrupted until the end of the sample, given that the country was also an independent nation during the entire period; does not count foreign occupation during World War II as an interruption of democracy; sources: PT and BMVW |

Distance to brussels |

The distance between Brussels and the capital of a country in kilometers; source: Centre d’Etudes Prospectives et d’Informations Internationales (CEPII) |

Federalism |

Dummy variable equal to 1 if a country has a federal political structure, 0 otherwise; source: Forum of Federations (2002): List of Federal Countries |

GDP |

Total GDP at current prices in USD billion; sources: International Monetary Fund (IMF) World Economic Outlook (WEO) |

High courts |

The number of high courts; source: Voigt (2012) |

IGO |

The number of international governmental organizations working within a country; source: Paxton (2002) |

Incoming cases |

The number of incoming first-instance cases per 100,000 inhabitants in 2008; source: European Commission for the Efficiency of Justice (CEPEJ 2010) |

Industry |

The industry value added as a share of GDP; source: WDI |

INGO |

The number of international NGOs working within a country; source: Paxton (2002) |

Insurance and financial services |

Insurance and financial service activity as a percentage of commercial service exports; source: WDI |

INTRA-EU trade |

Sum of intra-EU exports plus intra-EU imports measured as a share of GDP; sources: CM (2005), Eurostat Yearbooks, and WEO |

Judical review |

Equals 1 if the country has an ‘Austrian’ system of judicial review; 0 otherwise |

Law students |

The number of law students graduating from the College of Europe by nationality; source: College of Europe |

Legal origin |

The legal origin of each jurisdiction: (1) common law, (2) French, (3) German, or (4) Scandinavian; source: Zweigert and Kötz (1998) |

Monism |

Coded 0 if domestic constitutional law has supremacy over international law, 0.5 if international law has supremacy over ordinary domestic law, and 1 if international law has supremacy over domestic constitutional law; source: Voigt (2010) |

New EU member (CEE) |

Equals 1 if the country is one of the 12 central and eastern European nations that joined the EU in either May 2004 or January 2007; 0 otherwise |

Political discussion |

The population’s average response from two surveys in a given year; answers to the question ‘When you get together with friends, would you say you discuss political matters frequently, occasionally, or never?’ are coded as follows: (0) never, (1) occasionally, and (2) frequently; higher values thus indicate greater involvement in political discussion; source: Eurobarometer Surveys |

Protestantism |

Percentage of a country’s population professing the Protestant religion in 1980 (younger states are counted based on their average from 1990 to 1995); sources: PT and BMVW |

Students |

The number of students graduating from the College of Europe by nationality; source: College of Europe |

Support for European integration |

The population’s average response from two surveys in a given year; we calculate the percentage of respondents in a country and year that consider EU membership a ‘good thing’ and subtract from it the percentage of respondents that consider it a ‘bad thing’; source: Eurobarometer Surveys |

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Hornuf, L., Voigt, S. Analyzing preliminary references as the powerbase of the European Court of Justice. Eur J Law Econ 39, 287–311 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10657-014-9449-9

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10657-014-9449-9