Kairomones: Finding the fish factor

In a very simplified version of the food chain found in lakes, microalgae are eaten by water fleas called Daphnia, which are in turn eaten by fish. But things get complicated very quickly if observed in more detail. Algae release toxins to defend themselves, and form long chains to evade predators (Van Donk et al., 2011), while Daphnia can change shape or move to avoid being eaten by fish.

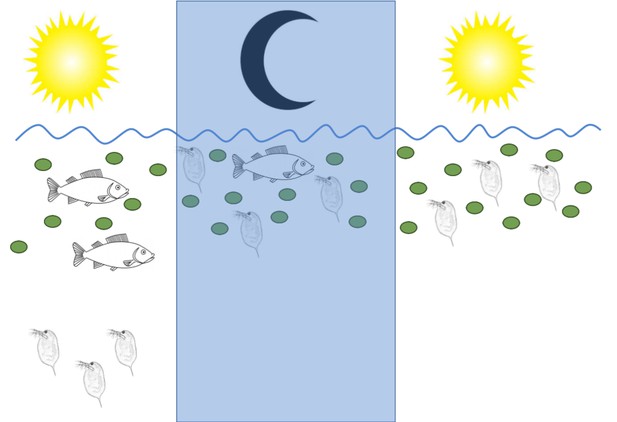

One way that Daphnia and other members of the zooplankton avoid predators is by moving to different depths of the lake depending on the time of day, a strategy known as diel vertical migration. If the surrounding water contains fish, Daphnia move to darker, deeper regions during the day, so that the fish cannot see them (Figure 1), and move to the upper layers of the water column – where the microalgae live – at night. If there are not many fish in the vicinity, Daphnia stay near the surface during the day as well (Lampert, 1989).

Daphnia water fleas change their behavior if fish are present.

Left: During the day Daphnia migrate to deeper, darker regions of the lake if they detect chemical signals called kairomones (not shown) that are released by fish. Middle: At night, when fish cannot see them, Daphnia move up to the water near the surface to eat the microalgae (green circles) that are plentiful there. Right: When no fish are present, there are no kairomones to detect, and Daphnia stay near the surface day and night.

Prey species must balance their resources carefully. Unnecessarily avoiding predators costs energy and can restrict access to food – the microalgae eaten by Daphnia do not live in the dark depths of the lake – but accidentally encountering a predator can be fatal. As a result, some species have adapted to detect chemicals released by predators. The identification of several of these chemicals, called kairomones, has opened up new areas of research in aquatic ecology, conservation and aquaculture (Yasumoto et al., 2005; Selander et al., 2015; Weiss et al., 2018).

The search for the kairomone that induces diel vertical migration, also known as the ‘fish factor’, has been ongoing for decades, with spectacular failures and misinterpretations on the way (see Pohnert and von Elert, 2000 for a discussion). Numerous obstacles have complicated the search: the fish factor occurs in low concentrations in lake water, and bioassay experiments that could identify it are problematic because it is difficult to monitor the vertical movement of Daphnia in a laboratory setting. Now, in eLife, Meike Hahn, Christoph Effertz, Laurent Bigler and Eric von Elert report the identity of this kairomone (Hahn et al., 2019).

Hahn et al. – who are based at the University of Cologne and the University of Zurich – used a bioassay-guided fractionation method to identify the fish factor. A technique called High Performance Liquid Chromatography allowed water in which fish had previously been incubated to be separated into ‘fractions’ that each contained a subset of chemicals. Examining the effect of each fraction on the migration behavior of Daphnia revealed one that induced diel vertical migration even though fish were not present. Hahn et al. identified the active chemical as 5α-cyprinol sulfate. Only picomolar concentrations of this compound are found in water inhabited by fish, but even these low concentrations are sufficient to change the migration behavior of Daphnia.

Since the release of kairomones places predator species at a disadvantage, a prey species can only rely on them if the predator cannot shut down the production of the molecule. This is the case for 5α-cyprinol sulfate, which is a bile acid that plays an essential role in digesting dietary fats (Hofmann et al., 2010). The fish release 5α-cyprinol sulfate from their intestine, gills, and the urinary tract. As this molecule is also stable in water, it reliably indicates the presence of fish to Daphnia.

Besides the many implications for basic research, the finding that only picomolar amounts of a compound can trigger widespread behavioral responses in a lake also raises ecotoxicological concerns. While we survey our waters for metabolites that cause immediate toxicity, we completely ignore the fact that non-toxic doses of such highly potent signaling chemicals can also have a substantial effect on an ecosystem. This calls for a new evaluation of the routine procedures used in environmental monitoring.

Kairomones are not the only chemical signals used by the species that inhabit lakes. Pheromones (Frenkel et al., 2014), defense metabolites and molecules that help species to outcompete each other also contribute to the intricate signaling mechanisms in aquatic ecosystems (Berry et al., 2008). We can conclude that these environments are really shaped by a diverse chemical landscape, a language of life that we are only just beginning to understand.

References

-

Pheromone signaling during sexual reproduction in algaeThe Plant Journal 79:632–644.https://doi.org/10.1111/tpj.12496

-

Bile salts of vertebrates: structural variation and possible evolutionary significanceJournal of Lipid Research 51:226–246.https://doi.org/10.1194/jlr.R000042

-

The adaptive significance of diel vertical migration of zooplanktonFunctional Ecology 3:21–27.https://doi.org/10.2307/2389671

-

No ecological relevance of trimethylamine in fish–Daphnia interactionsLimnology and Oceanography 45:1153–1156.https://doi.org/10.4319/lo.2000.45.5.1153

-

Identification of Chaoborus kairomone chemicals that induce defences in DaphniaNature Chemical Biology 14:1133–1139.https://doi.org/10.1038/s41589-018-0164-7

Article and author information

Author details

Publication history

- Version of Record published: June 11, 2019 (version 1)

Copyright

© 2019, Pohnert

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use and redistribution provided that the original author and source are credited.

Metrics

-

- 1,815

- views

-

- 123

- downloads

-

- 76

- citations

Views, downloads and citations are aggregated across all versions of this paper published by eLife.

Download links

Downloads (link to download the article as PDF)

Open citations (links to open the citations from this article in various online reference manager services)

Cite this article (links to download the citations from this article in formats compatible with various reference manager tools)

Further reading

-

- Ecology

- Epidemiology and Global Health

Zoonotic disease dynamics in wildlife hosts are rarely quantified at macroecological scales due to the lack of systematic surveys. Non-human primates (NHPs) host Plasmodium knowlesi, a zoonotic malaria of public health concern and the main barrier to malaria elimination in Southeast Asia. Understanding of regional P. knowlesi infection dynamics in wildlife is limited. Here, we systematically assemble reports of NHP P. knowlesi and investigate geographic determinants of prevalence in reservoir species. Meta-analysis of 6322 NHPs from 148 sites reveals that prevalence is heterogeneous across Southeast Asia, with low overall prevalence and high estimates for Malaysian Borneo. We find that regions exhibiting higher prevalence in NHPs overlap with human infection hotspots. In wildlife and humans, parasite transmission is linked to land conversion and fragmentation. By assembling remote sensing data and fitting statistical models to prevalence at multiple spatial scales, we identify novel relationships between P. knowlesi in NHPs and forest fragmentation. This suggests that higher prevalence may be contingent on habitat complexity, which would begin to explain observed geographic variation in parasite burden. These findings address critical gaps in understanding regional P. knowlesi epidemiology and indicate that prevalence in simian reservoirs may be a key spatial driver of human spillover risk.

-

- Computational and Systems Biology

- Ecology

Collaborative hunting, in which predators play different and complementary roles to capture prey, has been traditionally believed to be an advanced hunting strategy requiring large brains that involve high-level cognition. However, recent findings that collaborative hunting has also been documented in smaller-brained vertebrates have placed this previous belief under strain. Here, using computational multi-agent simulations based on deep reinforcement learning, we demonstrate that decisions underlying collaborative hunts do not necessarily rely on sophisticated cognitive processes. We found that apparently elaborate coordination can be achieved through a relatively simple decision process of mapping between states and actions related to distance-dependent internal representations formed by prior experience. Furthermore, we confirmed that this decision rule of predators is robust against unknown prey controlled by humans. Our computational ecological results emphasize that collaborative hunting can emerge in various intra- and inter-specific interactions in nature, and provide insights into the evolution of sociality.