Published online Mar 15, 2021. doi: 10.4251/wjgo.v13.i3.161

Peer-review started: November 22, 2020

First decision: December 17, 2020

Revised: December 31, 2020

Accepted: February 4, 2021

Article in press: February 4, 2021

Published online: March 15, 2021

The association between body mass index (BMI) and clinical outcomes remains unclear among patients with resectable gastric cancer.

To investigate the relationship between BMI and long-term survival of gastric cancer patients.

This retrospective study included 2526 patients who underwent radical gastrectomy for gastric cancer between September 2013 and June 2018. The patients were divided into four groups: Group A (low BMI, < 18.5 kg/m2), group B (normal BMI, 18.5-24.9 kg/m2), group C (overweight, 25-29.9 kg/m2), and group D (obese, ≥ 30 kg/m2). Clinicopathological findings and survival outcomes were recorded and analyzed.

Preoperative weight loss was more common in the low-BMI group, while diabetes was more common in the obese group. Upper-third gastric cancer accounted for a large proportion of cases in the higher BMI groups. Major perioperative complications tended to increase with BMI. The 5-year overall survival rates were 66.4% for group A, 75.0% for group B, 77.1% for group C, and 78.6% for group D. The 5-year overall survival rate was significantly lower in group A than in group C (P = 0.008) or group D (P = 0.031). Relative to a normal BMI value, a BMI of < 18.5 kg/m2 was associated with poor survival (hazard ratio: 1.558, 95% confidence interval: 1.125-2.158, P = 0.008).

Low BMI, but not high BMI, independently predicted poor survival in patients with resectable gastric cancer.

Core Tip: The association between body mass index (BMI) and clinical outcomes remains unclear among patients with resectable gastric cancer. The findings of this study suggest that low BMI may result in unfavorable long-term outcomes among patients with resectable gastric cancer. The factor associated with poor overall survival based on multivariate analysis was low BMI, rather than high BMI.

- Citation: Ma S, Liu H, Ma FH, Li Y, Jin P, Hu HT, Kang WZ, Li WK, Xiong JP, Tian YT. Low body mass index is an independent predictor of poor long-term prognosis among patients with resectable gastric cancer. World J Gastrointest Oncol 2021; 13(3): 161-173

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5204/full/v13/i3/161.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4251/wjgo.v13.i3.161

Gastric cancer is the fifth most common cancer and the third leading cause of cancer-related death[1]. Gastric cancer patients often experience malnutrition, which may lead to obvious weight loss before surgery[2], particularly at advanced stages of the disease[3]. However, obesity is becoming increasingly common in both Western and Eastern countries[4,5]. Some studies have examined the association between body mass index (BMI) and the prognosis of gastric cancer[6-15], although the long-term outcomes remain unclear for patients with different BMIs.

Low preoperative BMI is associated with poor long-term outcomes among patients with gastric cancer[6,7], which may highlight the clinical importance of preoperative weight loss. However, some studies have claimed that BMI is not a risk factor for poor survival[8,9], while others have suggested that overweight/obese gastric cancer patients have a higher risk of postoperative complications and experience poorer outcom-es[10,11]. Moreover, different studies have indicated that a high BMI is not associated with an increased risk of perioperative complications[12,13], and that patients with gastric cancer and a high BMI have comparable or better long-term outcomes, relative to individuals with a normal BMI[14,15]. Considering the discrepancies in these findings, this retrospective study aimed to clarify the relationship between preoperative BMI and long-term prognosis among patients with resectable gastric cancer.

The study included 3370 patients who were diagnosed with primary gastric cancer and underwent radical gastrectomy at the Department of Pancreatic and Gastric Surgery, National Cancer Center/Cancer Hospital, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences, and Peking Union Medical College between September 2013 and June 2018. The retrospective study protocol was approved by the institutional review board of the National Cancer Center/Cancer Hospital, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences, and Peking Union Medical College.

The inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) Primary gastric adenocarcinoma; (2) A single focal tumor; (3) An available comprehensive pathological report; (4) Age 18–75 years; (5) An Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group score of 0–2; and (6) No chronic diseases involving major organs (heart, liver, or kidney). The exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) History of surgery (565 patients excluded); (2) Benign or malignant tumor history (49 patients were excluded); (3) M1 status confirmed during surgery (122 patients excluded); and (4) Incomplete clinicopathological information (108 patients excluded). Thus, the present study analyzed data from 2526 eligible patients.

Radical gastrectomy was performed for all eligible patients according to the Japanese gastric cancer treatment guidelines[16]. Surgical procedures included proximal, total, and distal gastrectomy. After surgery, specimens were reviewed by pathologists at the Department of Pancreatic and Gastric Surgery, National Cancer Center/Cancer Hospital, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences, and Peking Union Medical College. The pathological Tumor-node-metastasis (pTNM) stage was assessed according to the 8th edition American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) TNM cancer staging guidelines[17]. Perioperative management was performed according to routine practice and did not differ between the groups. The patients’ medical records were reviewed to collect data regarding clinicopathological characteristics: Sex, age, preoperative weight loss (%), preoperative BMI, diabetes, tumor location, Borrmann classification, histological type, perineural invasion, lymphovascular invasion (LVI), pTNM stage, examined lymph nodes (eLNs), metastatic lymph nodes, major complications (Clavien-Dindo classification of ≥ III), and survival.

BMI was classified as very obese (≥ 35 kg/m2), obese (30.0-34.9 kg/m2), overweight (25.0-29.9 kg/m2), and normal weight (18.5-24.9 kg/m2) according to the World Health Organization (WHO) guidelines[18]. However, the present study only included a small number of very obese patients; therefore, the very obese and obese groups were combined. Thus, in the present study, we assigned the patients into four groups: Group A (low BMI, < 18.5 kg/m2), group B (normal BMI, 18.5-24.9 kg/m2), group C (overweight, 25-29.9 kg/m2), and group D (obese, ≥ 30 kg/m2).

Data were compared between the four groups to identify differences in postoperative outcomes (major complications) and long-term survival. Categorical variables were compared using the χ2 test and non-normally distributed continuous variables were compared using Kruskal-Wallis one-way analysis of variance. Survival outcomes were compared using the Kaplan-Meier life table method and the log-rank test. Cox proportional hazards models were used to assess the associations between the predictor variables and outcomes. Results were considered statistically significant at P values of < 0.05. All statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics software (version 23 for Mac, IBM Corp.), R software (version 4.0.2 for Mac, IBM Corp.), and Prism 7 software for Mac (IBM Corp.).

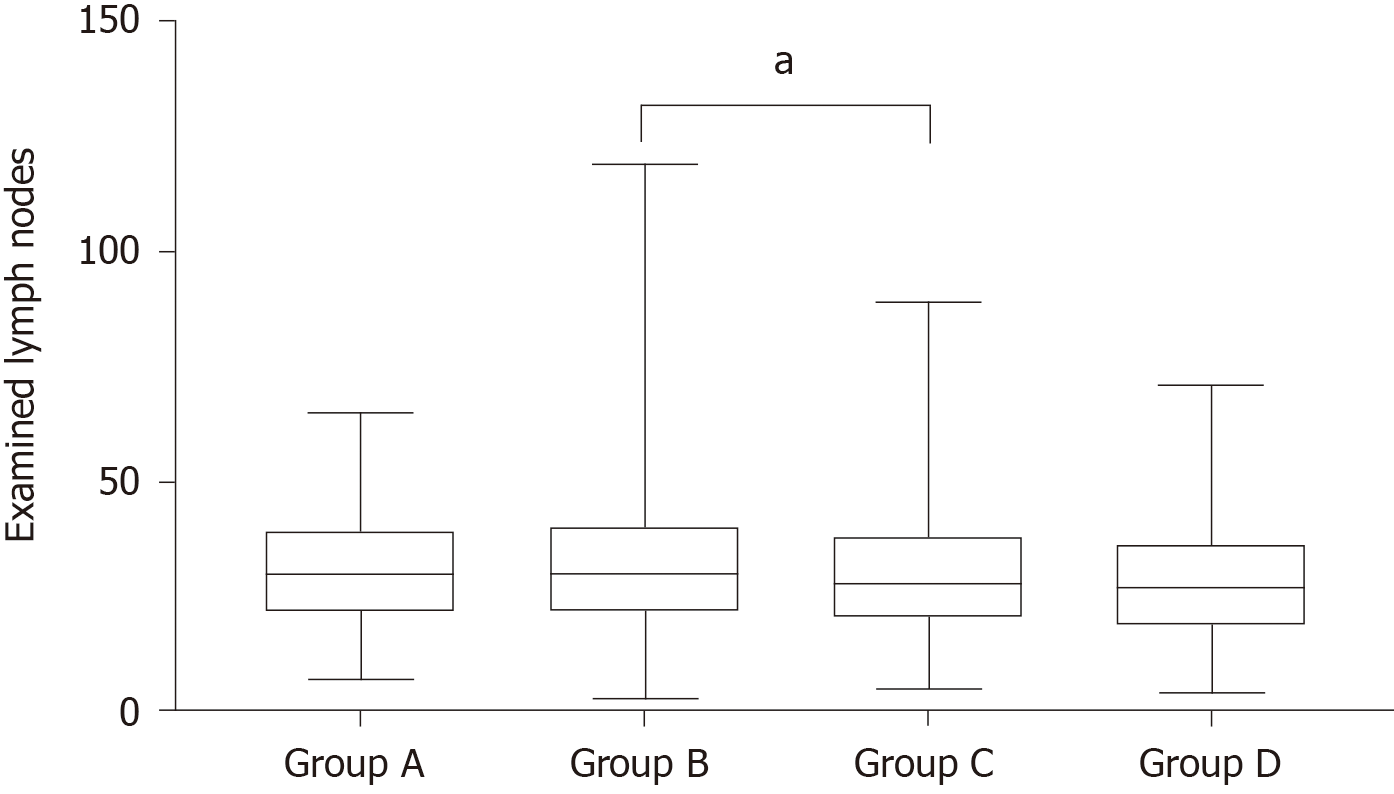

The study included 2526 patients who were treated between September 2013 and June 2018 (Table 1). All patients underwent radical gastrectomy. Significant differences in sex were observed among the four groups. The low BMI group had a greater proportion of preoperative weight loss and a lower proportion of diabetes. The proportion of upper-third gastric cancer tended to increase with increasing BMI. Significant differences in the number of eLNs were also observed among the four groups (Table 1 and Figure 1). In a paired comparison (Figure 1), more lymph nodes were harvested for group B than for group C (median: 30 vs 28, P = 0.021). Increasing BMI tended to be associated with an increased incidence of major complications (Table 1). There were no significant differences in the other clinicopathological characteristics among the four groups.

| Group A | Group B | Group C | Group D | P value | |

| Male sex, n (%) | 73 (61.3) | 1124 (77.1) | 713 (85.1) | 84 (75.0) | < 0.001 |

| Age < 65 yr, n (%) | 79 (66.4) | 1067 (73.2) | 615 (73.4) | 79 (70.5) | 0.384 |

| Preoperative weight loss, n (%) | < 0.001 | ||||

| 0% or increased | 75 (63.0) | 1010 (63.9) | 623 (74.3) | 89 (79.5) | |

| 0-5% | 7 (5.9) | 127 (8.7) | 88 (10.5) | 10 (8.9) | |

| > 5% | 37 (31.1) | 320 (22.0) | 127 (15.2) | 13 (11.6) | |

| BMI, median (range) | 17.1 (14.0-18.4) | 22.5 (18.5-24.9) | 26.7 (25.0-29.9) | 31.2 (30.0-48.8) | < 0.001 |

| Diabetes, n (%) | 3 (2.5) | 100 (6.9) | 107 (12.8) | 22 (19.6) | < 0.001 |

| Tumor location | 0.044 | ||||

| Upper | 41 (34.5) | 481 (33.0) | 337 (40.2) | 46 (41.1) | |

| Middle | 24 (20.2) | 294 (20.2) | 164 (19.6) | 24 (21.4) | |

| Lower | 49 (41.2) | 604 (41.5) | 308 (36.8) | 38 (33.9) | |

| Entire | 5 (4.2) | 78 (5.4) | 29 (3.5) | 4 (3.6) | |

| Tumor diameter ≤ 5 cm, n (%) | 857 (71.4) | 1019 (69.9) | 603 (72.0) | 83 (74.1) | 0.642 |

| Borrmann type, n (%) | 0.116 | ||||

| EGC | 26 (21.8) | 298 (20.5) | 181 (21.6) | 30 (26.8) | |

| I | 8 (6.7) | 112 (7.7) | 55 (6.6) | 13 (11.6) | |

| II | 30 (25.2) | 376 (25.8) | 247 (29.5) | 29 (25.9) | |

| III | 53 (44.5) | 582 (39.9) | 317 (37.8) | 34 (30.4) | |

| IV | 2 (1.7) | 89 (6.1) | 38 (4.5) | 6 (5.4) | |

| Histological type, n (%) | 0.931 | ||||

| Differentiated | 31 (26.1) | 351 (24.1) | 201 (24.0) | 25 (22.3) | |

| Undifferentiated | 88 (73.9) | 1106 (75.9) | 637 (76.0) | 87 (77.7) | |

| PNI, n (%) | 48 (40.3) | 701 (48.1) | 419 (50.0) | 49 (43.8) | 0.177 |

| LVI, n (%) | 41 (34.5) | 583 (40.0) | 322 (38.4) | 55 (49.1) | 0.105 |

| pT status, n (%) | 0.606 | ||||

| 1a | 13 (10.9) | 164 (11.3) | 78 (9.3) | 12 (10.7) | |

| 1b | 16 (13.4) | 216 (14.8) | 131 (15.6) | 21 (18.8) | |

| 2 | 18 (15.1) | 202 (13.9) | 119 (14.2) | 18 (16.1) | |

| 3 | 38 (31.9) | 434 (29.8) | 280 (33.4) | 34 (30.4) | |

| 4a | 29 (24.4) | 401 (27.5) | 198 (23.6) | 23 (20.5) | |

| 4b | 5 (4.2) | 40 (2.7) | 32 (3.8) | 4 (3.6) | |

| pN status, n (%) | 0.143 | ||||

| 0 | 50 (42.0) | 593 (40.7) | 344 (41.1) | 45 (40.2) | |

| 1 | 22 (18.5) | 276 (18.9) | 163 (19.5) | 18 (16.1) | |

| 2 | 18 (15.1) | 238 (16.3) | 137 (16.3) | 27 (24.1) | |

| 3a | 21 (17.6) | 169 (11.6) | 116 (13.8) | 13 (11.6) | |

| 3b | 8 (6.7) | 181 (12.4) | 78 (9.3) | 9 (8.0) | |

| pTNM stage, n (%) | 0.261 | ||||

| IA | 24 (20.2) | 307 (21.1) | 173 (20.6) | 29 (25.9) | |

| IB | 10 (8.4) | 156 (10.7) | 88 (10.5) | 9 (8.0) | |

| IIA | 17 (14.3) | 185 (12.7) | 99 (11.8) | 15 (13.4) | |

| IIB | 19 (16.0) | 202 (13.9) | 127 (15.2) | 14 (12.5) | |

| IIIA | 20 (16.8) | 253 (17.4) | 154 (18.4) | 21 (18.8) | |

| IIIB | 22 (18.5) | 173 (11.9) | 124 (14.8) | 15 (13.4) | |

| IIIC | 7 (5.9) | 181 (12.4) | 73 (8.7) | 9 (8.0) | |

| eLNs, median (range) | 30 (7-65) | 30 (3-119) | 28 (5-89) | 27 (4-71) | 0.008 |

| mLN, median (range) | 1 (0-24) | 1 (0-67) | 1 (0-48) | 2 (0-29) | 0.824 |

| Major complications, n (%) | 11 (9.2) | 200 (13.7) | 117 (14.0) | 28 (25.0) | 0.004 |

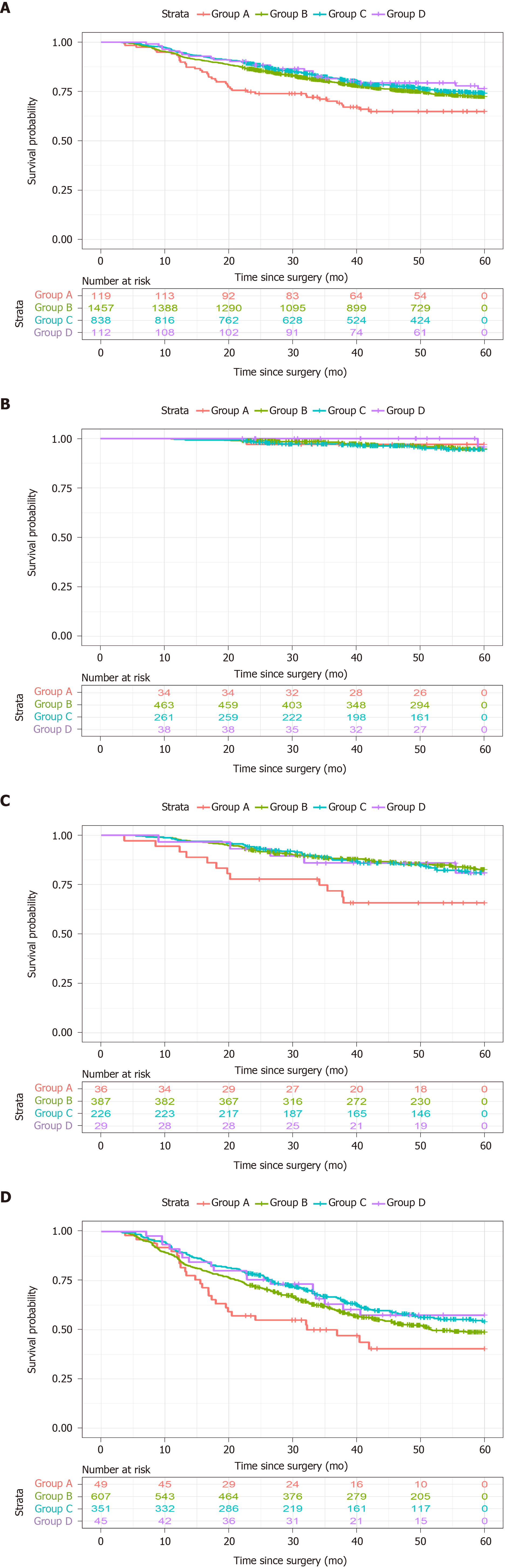

The median follow-up period was 50.2 mo, the median survival time was not reached, and 1906 patients (75.5%) were alive at the last follow-up. Figure 2 shows the Kaplan-Meier overall survival (OS) curves according to BMI classification. The 5-year OS rates were 66.4% for group A, 75.0% for group B, 77.1% for group C, and 78.6% for group D (P = 0.039, Figure 2A). Group A had poorer 5-year OS than group C (P = 0.008) and group D (P = 0.031). When the cases were stratified according to the pTNM stage, a significant difference was observed only for pTNM stage III disease (P = 0.041, Figure 2D). The results of the paired comparisons are shown in Table 2. Among patients with pTNM stage III disease, group A had poorer 5-year OS than group C (44.9% vs 59.5%, P = 0.006). Among patients with pTNM stage II disease, group A had poorer 5-year OS than group B (66.7% vs 84.8%, P = 0.03) and group C (66.7% vs 83.2%, P = 0.023).

| B | C | D | |

| A | 0.054/0.497/0.030/0.074 | 0.008/0.485/0.023/0.006 | 0.031/0.952/0.136/0.070 |

| B | 0.143/0.870/0.593/0.081 | 0.246/0.426/0.750/0.428 | |

| C | 0.605/0.414/0.886/0.964 |

The multivariate analyses (Table 3) revealed that a poor OS was independently associated with a BMI of < 18.5 kg/m2 [vs BMI of 18.5-24.9 kg/m2, hazard ratio (HR): 1.558, 95% confidence interval: 1.125-2.158, P = 0.008], upper-third gastric cancer or entire stomach involvement, tumor diameter > 5 cm, Borrmann type IV disease, LVI, pT3–4 status, pN+ status, and having < 30 eLNs. A high BMI (≥ 30 kg/m2) did not independently predict a poor long-term OS (vs BMI of 18.5-24.9 kg/m2, HR: 0.824, 95% confidence interval: 0.551-1.230, P = 0.343).

| Univariate | Multivariate1 | |||

| HR (95%CI) | P value | HR (95%CI) | P value | |

| Sex | ||||

| Male | Ref | Ref | ||

| Female | 0.897 (0.742-1.085) | 0.263 | 0.970 (0.798-1.180) | 0.763 |

| Age | ||||

| < 65 yr | Ref | Ref | ||

| ≥ 65 yr | 1.362 (1.162-1.598) | < 0.001 | 1.161 (0.985-1.367) | 0.075 |

| Preoperative weight loss | ||||

| 0% or increased | Ref | Ref | ||

| 0%–5% | 1.210 (0.934-1.568) | 0.148 | 0.964 (0.740-1.256) | 0.786 |

| > 5% | 1.612 (1.355-1.918) | < 0.001 | 1.122 (0.937-1.342) | 0.210 |

| BMI | ||||

| 18.5-24.9 kg/m2 | Ref | Ref | ||

| 25-29.9 kg/m2 | 0.883 (0.747-1.043) | 0.143 | 0.885 (0.746-1.049) | 0.160 |

| ≥ 30 kg/m2 | 0.792 (0.533-1.177) | 0.249 | 0.824 (0.551-1.230) | 0.343 |

| < 18.5 kg/m2 | 1.368 (0.996-1.880) | 0.053 | 1.558 (1.125-2.158) | 0.008 |

| Tumor location | ||||

| Lower | Ref | Ref | ||

| Middle | 1.049 (0.828-1.328) | 0.692 | 1.098 (0.863-1.395) | 0.447 |

| Upper | 1.886 (1.579-2.253) | < 0.001 | 1.409 (1.155-1.717) | 0.001 |

| Entire | 3.512 (2.639-4.674) | < 0.001 | 1.748 (1.292-2.366) | < 0.001 |

| Tumor diameter | ||||

| ≤ 5 cm | Ref | Ref | ||

| > 5 cm | 2.488 (2.141-2.892) | < 0.001 | 1.256 (1.068-1.477) | 0.006 |

| Borrmann type | ||||

| EGC | Ref | Ref | ||

| I | 4.861 (3.082-7.666) | < 0.001 | 1.206 (0.659-2.208) | 0.544 |

| II | 4.374 (2.971-6.440) | < 0.001 | 1.205 (0.685-2.120) | 0.518 |

| III | 8.817 (6.114-12.717) | < 0.001 | 1.587 (0.905-2.784) | 0.107 |

| IV | 14.778 (9.703-22.510) | < 0.001 | 1.967 (1.070-3.613) | 0.029 |

| Histological type | ||||

| Differentiated | Ref | Ref | ||

| Undifferentiated | 1.495 (1.237-1.806) | < 0.001 | 0.891 (0.724-10.96) | 0.275 |

| PNI | ||||

| No | Ref | Ref | ||

| Yes | 2.785 (2.390-3.246) | < 0.001 | 1.064 (0.886-1.278) | 0.507 |

| LVI | ||||

| No | Ref | Ref | ||

| Yes | 2.764 (2.355-3.243) | < 0.001 | 1.231 (1.039-1.457) | 0.016 |

| pT status | ||||

| 1a | Ref | Ref | ||

| 1b | 1.596 (0.778-3.274) | 0.202 | 1.343 (0.652-2.765) | 0.424 |

| 2 | 3.338 (1.727-6.454) | < 0.001 | 1.607 (0.749-3.451) | 0.223 |

| 3 | 9.302 (5.086-17.012) | < 0.001 | 2.519 (1.201-5.284) | 0.014 |

| 4a | 17.766 (9.732-32.433) | < 0.001 | 3.898 (1.844-8.239) | < 0.001 |

| 4b | 18.263 (9.415-35.427) | < 0.001 | 3.950 (1.778-8.775) | < 0.001 |

| pN status | ||||

| 0 | Ref | Ref | ||

| 1 | 3.055 (2.316-4.030) | < 0.001 | 1.787 (1.314-2.394) | < 0.001 |

| 2 | 4.849 (3.717-6.326) | < 0.001 | 2.544 (1.898-3.411) | < 0.001 |

| 3a | 9.325 (7.207-12.066) | < 0.001 | 4.095 (3.042-5.512) | < 0.001 |

| 3b | 11.071 (8.540-14.352) | < 0.001 | 4.345 (3.182-5.932) | < 0.001 |

| eLNs | ||||

| ≥ 30 | Ref | Ref | ||

| 16–29 | 1.055 (0.901-1.236) | 0.505 | 1.282 (1.083-1.518) | 0.004 |

| < 16 | 0.944 (0.724-1.232) | 0.672 | 1.515 (1.139-2.015) | 0.004 |

Obesity is associated with cancer mortality, and the malnutrition status of cancer patients may also be related to their long-term prognosis. However, the relationships between specific BMI groupings and cancer survival are less clear. The results of the present study suggest that low BMI independently predicted poor long-term survival, while high BMI was associated with major perioperative complications but not long-term survival.

Our group with high BMI had an increased proportion of diabetes, upper-third gastric cancer, and perioperative major complications. Similarly, a meta-analysis suggested that high BMI was associated with an increased incidence of cardiac carcinoma. In this context, obese patients are more likely to have esophagogastric junction disruption or an augmented gastroesophageal pressure gradient, which could induce reflux[19]. In addition, gastroesophageal reflux disease is strongly associated with cardiac or esophageal adenocarcinoma[20]. However, this distribution pattern was not observed in other studies[6,12].

Several studies have indicated that high BMI is associated with increased risks of major complications and perioperative mortality[9,20,21], which is consistent with our findings. Obese patients typically have poor surgical field visibility, as well as an increased possibility of oozing, which can complicate the dissection of lymph nodes and formation of an anastomosis. However, high BMI was not associated with an increased risk of perioperative complications in some medical centers[8,22-24], which could be related to high volumes and experienced surgeons reducing the risks associated with radical gastrectomy in obese patients[12]. In our study, fewer eLNs were retrieved in the higher BMI groups (groups C and D), although the only significant difference was observed between groups B and C, and these two groups had similar 5-year OS outcomes. Dhar et al[10] reported that a higher BMI was associated with a higher risk of local recurrence and shorter recurrence-free survival, which they attributed to the difficulty in achieving adequate lymphadenectomy in obese patients with gastric cancer. In addition, it can be challenging to determine the actual number of lymph node dissections in obese patients, considering the difficulty involved in isolating lymph nodes within the abundant intra-abdominal fat. Nevertheless, as indicated above, it is possible that experienced surgeons in high-volume centers might be able to perform appropriate radical lymphadenectomy and achieve favorable oncological outcomes even for obese patients. In our study, the median number of eLNs was similar for groups B and C, and the difference might be attributable to the difference in the range, rather than a difference in the median value. Nevertheless, we observed that an inadequate number of eLNs (< 30) was an independent predictor of poor long-term outcomes, which is consistent with the increasing number of studies[25-27] that suggest that a higher number of retrieved LNs is associated with improved long-term outcomes. The 8th edition of the AJCC TNM cancer staging guidelines[17] recommend that a minimum of 16 LNs, but preferably ≥ 30 LNs, be assessed during gastric cancer surgery. In addition, Deng et al[28,29] demonstrated that an insufficient number of eLNs may be a risk factor for postoperative recurrence in patients with LN-negative gastric cancer. We emphasize the importance of standard radical gastrectomy procedures and a sufficient number of eLNs for obese patients to achieve favorable short-term and oncological outcomes. Less experienced surgeons should perform D2 lymphadenectomy for obese patients with gastric cancer until they have sufficient experience.

In our study, low BMI (< 18.5 kg/m2) was an independent predictor of poor 5-year OS, although comparable 5-year OS rates were observed between the low and normal BMI groups. Patients with advanced gastric cancer are more likely to experience preoperative weight loss and malnutrition, which is associated with decreased survival. Moreover, gastrectomy leads to postoperative weight loss[15], and it is possible that overweight/obese patients would reach a more appropriate body weight after surgery, which could improve their long-term prognosis. Our multivariate analysis revealed that high BMI was not associated with poor survival, and a similar result was observed in a retrospective study of 427 Japanese patients with gastric cancer by Wada et al[7]. In the present study, stratified analyses revealed a difference in the 5-year OS rates when we compared the low-BMI and overweight groups of patients with pTNM stage II–III disease. Nevertheless, the 5-year OS rates were comparable between the four BMI-based groups of patients with pTNM stage I gastric cancer. The discrepancies between the results of the overall and stratified analyses may be related to the limited numbers of patients in groups A and D, which might have biased the stratified analysis.

Previous studies have supported different conclusions regarding the association between BMI and long-term prognosis[6-15]. Our results suggest that patients with obese and normal BMI have comparable 5-year OS rates, while conflicting results have been reported[11,13]. We speculate that these differences might be related to the specific group divisions, as only two BMI-based groups (cut-off: 25 kg/m2) were used in the studies by Lianos et al[11] and Shimada et al[13], who concluded that high BMI independently predicted a poor prognosis. Three BMI-based groups (< 18.5 kg/m2, 18.5-24.9 kg/m2, and ≥ 25 kg/m2) were used in a Chinese and a Japanese study[7,9], which revealed that low BMI, rather than high BMI, was associated with poor survival, similar to our findings. The main difference between these studies was that a BMI of < 25 kg/m2 was analyzed either as a single group or by separating into two groups (< 18.5 kg/m2 and 18.5-24.9 kg/m2). Furthermore, Shimada et al[13] reported average BMI values of 26.4 ± 2 kg/m2 in the obese group and 22 ± 2.2 kg/m2 in the normal-BMI group, which are clearly different from the values in our study. The differences in average BMI values might explain the conflicting conclusions. Nevertheless, there has been a recent shift toward the general opinion that high BMI does not affect long-term outcomes among gastric cancer patients, particularly those who are treated in high-volume medical centers[12].

The present study has several limitations. First, we did not analyze data regarding adjuvant chemotherapy use, which might have influenced the patients’ outcomes. Second, the surgical approach was not considered in this study, although surgical procedures can influence postoperative nutritional status and long-term outcomes, especially after total or near-total gastrectomy[30-32]. Third, the stratified analysis might have been biased based on the small numbers of patients in groups A and D.

A low BMI (< 18.5 kg/m2) was an independent risk factor for poor long-term survival after radical gastrectomy for gastric cancer. However, a high BMI was not a risk factor for poor survival in this setting.

Some studies showed that high body mass index (BMI) was related to unfavorable prognosis of gastric cancer, while other literature revealed low preoperative BMI was related to unfavorable prognosis of gastric cancer. To our knowledge, there are still discrepancies in the relationship between BMI and prognosis of gastric cancer.

Considering the controversy mentioned above, our study aimed to clarify the relationship between preoperative BMI and long-term prognosis among patients with resectable gastric cancer.

The aim of this study was to clarify the relationship between BMI and long-term prognosis of resectable gastric cancer patients. Clinicopathological characteristics and survival were analyzed in our study. Then, multivariate analysis was used to identify risk factors. Our findings suggest that low BMI may result in unfavorable long-term outcomes among patients with resectable gastric cancer. The factor associated with poor overall survival based on multivariate analysis was low BMI, rather than high BMI.

This is a retrospective study. 2526 patients who had undergone radical gastrectomy for gastric cancer at the Cancer Hospital of the Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences were eligible and finally included in the study. Medical records were reviewed with regard to sex, age, preoperative weight loss (%), preoperative BMI, diabetes, tumor location, Borrmann classification, histological type, perineural invasion, lymphova-scular invasion, pathological tumor-node-metastasis stage, examined lymph nodes, metastatic lymph nodes, major complications (Clavien-Dindo classification of ≥ III), and follow-up data. Cumulative survival rates were obtained using the Kaplan–Meier method and compared using the log-rank test to evaluate statistically significant differences. Cox proportional hazards regression analysis was used to evaluate risk factors for poor overall survival.

Preoperative weight loss was more common in the low-BMI group, while diabetes was more common in the obese group. Upper-third gastric cancer accounted for a large proportion of cases in the higher BMI groups. Major perioperative complications tended to increase with BMI. The 5-year overall survival rates were lower in the low BMI group. Relative to a normal BMI value, low BMI was associated with poor survival.

Low BMI resectable gastric cancer patients have an unfavorable long-term outcome. Low BMI is an independent predictor of poor long-term prognosis. Disputed conclusions in previous literature regarding the relationship between BMI and long-term prognosis for resectable gastric cancer may be attributed to different cut-off values for BMI group division.

Low BMI independently predicted poor survival among patients with resectable gastric cancer. Thus, additional treatment strategies should be undertaken in the management of gastric cancer patients with a low preoperative BMI.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Oncology

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Guglielmi FW S-Editor: Fan JR L-Editor: Webster JR P-Editor: Li JH

| 1. | Bray F, Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Siegel RL, Torre LA, Jemal A. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2018;68:394-424. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 53206] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 50764] [Article Influence: 8460.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (44)] |

| 2. | Kim JM, Park JH, Jeong SH, Lee YJ, Ju YT, Jeong CY, Jung EJ, Hong SC, Choi SK, Ha WS. Relationship between low body mass index and morbidity after gastrectomy for gastric cancer. Ann Surg Treat Res. 2016;90:207-212. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 15] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Stratton RJ, Green CJ, Elia M. Disease-related malnutrition: an evidence-based approach to treatment. 1st ed. CABI; 2003. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 4. | Singh GK, Siahpush M, Hiatt RA, Timsina LR. Dramatic increases in obesity and overweight prevalence and body mass index among ethnic-immigrant and social class groups in the United States, 1976-2008. J Community Health. 2011;36:94-110. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 160] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 170] [Article Influence: 13.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Lin X, Xu Y, Xu J, Pan X, Song X, Shan L, Zhao Y, Shan PF. Global burden of noncommunicable disease attributable to high body mass index in 195 countries and territories, 1990-2017. Endocrine. 2020;69:310-320. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 32] [Article Influence: 8.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Feng F, Zheng G, Guo X, Liu Z, Xu G, Wang F, Wang Q, Guo M, Lian X, Zhang H. Impact of body mass index on surgical outcomes of gastric cancer. BMC Cancer. 2018;18:151. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 27] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Wada T, Kunisaki C, Ono HA, Makino H, Akiyama H, Endo I. Implications of BMI for the Prognosis of Gastric Cancer among the Japanese Population. Dig Surg. 2015;32:480-486. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 21] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Kim JH, Chin HM, Hwang SS, Jun KH. Impact of intra-abdominal fat on surgical outcome and overall survival of patients with gastric cancer. Int J Surg. 2014;12:346-352. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 24] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Lin YS, Huang KH, Lan YT, Fang WL, Chen JH, Lo SS, Hsieh MC, Li AF, Chiou SH, Wu CW. Impact of body mass index on postoperative outcome of advanced gastric cancer after curative surgery. J Gastrointest Surg. 2013;17:1382-1391. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 23] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Dhar DK, Kubota H, Tachibana M, Kotoh T, Tabara H, Masunaga R, Kohno H, Nagasue N. Body mass index determines the success of lymph node dissection and predicts the outcome of gastric carcinoma patients. Oncology. 2000;59:18-23. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 114] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 121] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Lianos GD, Bali CD, Glantzounis GK, Katsios C, Roukos DH. BMI and lymph node ratio may predict clinical outcomes of gastric cancer. Future Oncol. 2014;10:249-255. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 12] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Voglino C, Di Mare G, Ferrara F, De Franco L, Roviello F, Marrelli D. Clinical and Oncological Value of Preoperative BMI in Gastric Cancer Patients: A Single Center Experience. Gastroenterol Res Pract. 2015;2015:810134. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 12] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Shimada S, Sawada N, Ishiyama Y, Nakahara K, Maeda C, Mukai S, Hidaka E, Ishida F, Kudo SE. Impact of obesity on short- and long-term outcomes of laparoscopy assisted distal gastrectomy for gastric cancer. Surg Endosc. 2018;32:358-366. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 32] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Ojima T, Iwahashi M, Nakamori M, Nakamura M, Naka T, Ishida K, Ueda K, Katsuda M, Iida T, Tsuji T, Yamaue H. Influence of overweight on patients with gastric cancer after undergoing curative gastrectomy: an analysis of 689 consecutive cases managed by a single center. Arch Surg. 2009;144:351-8; discussion 358. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 66] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 63] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Tokunaga M, Hiki N, Fukunaga T, Ohyama S, Yamaguchi T, Nakajima T. Better 5-year survival rate following curative gastrectomy in overweight patients. Ann Surg Oncol. 2009;16:3245-3251. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 68] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 71] [Article Influence: 5.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Japanese Gastric Cancer Association. Japanese gastric cancer treatment guidelines 2014 (ver. 4). Gastric Cancer. 2017;20:1-19. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 1575] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 1793] [Article Influence: 256.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Doescher J, Veit JA, Hoffmann TK. [The 8th edition of the AJCC Cancer Staging Manual: Updates in otorhinolaryngology, head and neck surgery]. HNO. 2017;65:956-961. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 70] [Article Influence: 14.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | World Health Organization. WHO Global Database on Body Mass Index. Available from: http://apps.who.int/bmi/index.jsp?introPage=intro_3.html. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 19. | Pandolfino JE, El-Serag HB, Zhang Q, Shah N, Ghosh SK, Kahrilas PJ. Obesity: a challenge to esophagogastric junction integrity. Gastroenterology. 2006;130:639-649. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 379] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 337] [Article Influence: 18.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Oh SJ, Hyung WJ, Li C, Song J, Rha SY, Chung HC, Choi SH, Noh SH. Effect of being overweight on postoperative morbidity and long-term surgical outcomes in proximal gastric carcinoma. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;24:475-479. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 24] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Pata G, Solaini L, Roncali S, Pasini M, Ragni F. Impact of obesity on early surgical and oncologic outcomes after total gastrectomy with "over-D1" lymphadenectomy for gastric cancer. World J Surg. 2013;37:1072-1081. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 22] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Kulig J, Sierzega M, Kolodziejczyk P, Dadan J, Drews M, Fraczek M, Jeziorski A, Krawczyk M, Starzynska T, Wallner G; Polish Gastric Cancer Study Group. Implications of overweight in gastric cancer: A multicenter study in a Western patient population. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2010;36:969-976. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 54] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Gretschel S, Christoph F, Bembenek A, Estevez-Schwarz L, Schneider U, Schlag PM. Body mass index does not affect systematic D2 lymph node dissection and postoperative morbidity in gastric cancer patients. Ann Surg Oncol. 2003;10:363-368. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 39] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Wong J, Rahman S, Saeed N, Lin HY, Almhanna K, Shridhar R, Hoffe S, Meredith KL. Effect of body mass index in patients undergoing resection for gastric cancer: a single center US experience. J Gastrointest Surg. 2014;18:505-511. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 24] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Kim JP, Lee JH, Kim SJ, Yu HJ, Yang HK. Clinicopathologic characteristics and prognostic factors in 10 783 patients with gastric cancer. Gastric Cancer. 1998;1:125-133. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 178] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 202] [Article Influence: 7.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Hayashi S, Kanda M, Ito S, Mochizuki Y, Teramoto H, Ishigure K, Murai T, Asada T, Ishiyama A, Matsushita H, Tanaka C, Kobayashi D, Fujiwara M, Murotani K, Kodera Y. Number of retrieved lymph nodes is an independent prognostic factor after total gastrectomy for patients with stage III gastric cancer: propensity score matching analysis of a multi-institution dataset. Gastric Cancer. 2019;22:853-863. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 29] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Smith DD, Schwarz RR, Schwarz RE. Impact of total lymph node count on staging and survival after gastrectomy for gastric cancer: data from a large US-population database. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:7114-7124. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 363] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 442] [Article Influence: 23.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Deng J, Liang H, Sun D, Zhang R, Zhan H, Wang X. Prognosis of gastric cancer patients with node-negative metastasis following curative resection: outcomes of the survival and recurrence. Can J Gastroenterol. 2008;22:835-839. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 41] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Deng J, Yamashita H, Seto Y, Liang H. Increasing the Number of Examined Lymph Nodes is a Prerequisite for Improvement in the Accurate Evaluation of Overall Survival of Node-Negative Gastric Cancer Patients. Ann Surg Oncol. 2017;24:745-753. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 52] [Article Influence: 6.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Seo HS, Jung YJ, Kim JH, Park CH, Kim IH, Lee HH. Long-Term Nutritional Outcomes of Near-Total Gastrectomy in Gastric Cancer Treatment: a Comparison with Total Gastrectomy Using Propensity Score Matching Analysis. J Gastric Cancer. 2018;18:189-199. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 5] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Ju T, Rivas L, Kurland K, Chen S, Sparks A, Lin PP, Vaziri K. National trends in total vs subtotal gastrectomy for middle and distal third gastric cancer. Am J Surg. 2020;219:691-695. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 1] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Ji X, Yan Y, Bu ZD, Li ZY, Wu AW, Zhang LH, Wu XJ, Zong XL, Li SX, Shan F, Jia ZY, Ji JF. The optimal extent of gastrectomy for middle-third gastric cancer: distal subtotal gastrectomy is superior to total gastrectomy in short-term effect without sacrificing long-term survival. BMC Cancer. 2017;17:345. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 29] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |