Abstract

Aims: The benefit of complete or incomplete percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) in patients with myocardial infarction and multivessel disease remains debated. The aim of our study was to compare a complete vs. a “culprit only” revascularisation strategy in patients with myocardial infarction distinguishing the different clinical subsets (STEMI and NSTEMI) and to provide one-year clinical outcome from the “real-life” BleeMACS (Bleeding complications in a Multicenter registry of patients discharged with diagnosis of Acute Coronary Syndrome) registry.

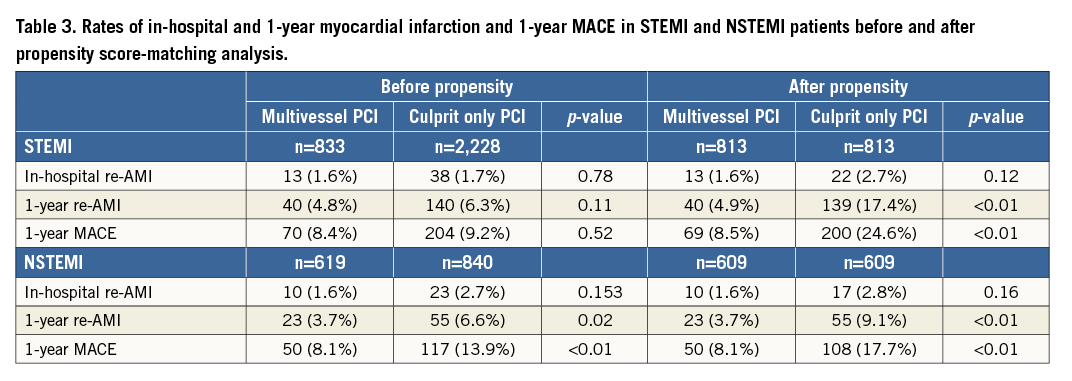

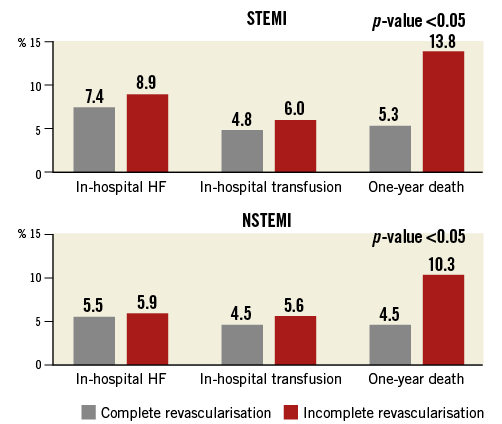

Methods and results: We conducted a multicentre study including all patients with myocardial infarction and multivessel coronary disease included in the BleeMACS (Bleeding complications in a Multicenter registry of patients discharged with diagnosis of Acute Coronary Syndrome) registry. They were divided into two groups, complete revascularisation (CR) and incomplete revascularisation (IR). The primary endpoint was the death rate at one-year follow-up. Secondary endpoints were in-hospital repeat myocardial infarction (re-AMI), in-hospital heart failure (HF), major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE) and myocardial infarction at one year. Four thousand five hundred and twenty patients were included in our analysis, with a diagnosis of STEMI in 67.7% and NSTEMI in 32.3%. CR was performed in 27.2% and 42.4%, respectively. At univariate analysis, in-hospital and one-year outcomes were similar between CR and IR in STEMI patients (all p-values >0.05). In NSTEMI patients, CR was associated with a lower one-year death rate (4.5% vs. 8.5%; p=0.002), re-AMI (3.7% vs. 6.6%; p=0.016) and MACE (8.1% vs. 13.9%; p=0.001). After propensity score matching, CR also reduced events in STEMI patients, including one-year mortality (5.3% vs. 13.8%; p<0.001), re-AMI (4.9% vs. 17.4%; p<0.001) and MACE (8.5% vs. 24.6%; p<0.001).

Conclusions: This multicentre retrospective registry showed the benefit of CR in terms of reduction of one-year mortality in patients with myocardial reinfarction and multivessel coronary disease. Randomised controlled trials including functional evaluation of the lesions should be performed to confirm our results.

Abbreviations

ANOVA: analysis of variance

BMS: bare metal stent

CKD: chronic kidney disease

CR: complete revascularisation

DES: drug-eluting stent

FFR: fractional flow reserve

HF: heart failure

IR: incomplete revascularisation

LVEF: left ventricular ejection fraction

MACE: major adverse cardiovascular events

NSTEMI: non-ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction

PCI: percutaneous coronary intervention

re-AMI: repeat myocardial infarction

SD: standard deviation

STEMI: ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction

Introduction

Almost half of all patients with myocardial infarction, both those with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) and those with non-ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (NSTEMI), present with multivessel disease1-3, a known predictor of worse cardiovascular prognosis4-6. Nevertheless, the benefit of incomplete (“culprit only lesion”) or complete (“culprit” and “non-culprit lesions”) percutaneous coronary revascularisation in patients with myocardial infarction is still debated.

Although the latest European STEMI Guidelines7 suggest complete revascularisation only for patients with cardiogenic shock or with persistent ischaemia after percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) of the supposed culprit lesion, the randomised PRAMI trial8 showed the superiority of a complete strategy in terms of composite cardiovascular outcomes at 23-month follow-up. These results were confirmed by Gershlick and colleagues in the CvLPRIT trial9, and supported by a recent meta-analysis which reported a long-term reduction in mortality of STEMI patients undergoing a multivessel staged revascularisation10.

Similar to the STEMI setting, there is uncertainty about the strategy of percutaneous revascularisation in NSTEMI multivessel patients.

American and European guidelines, although lacking a randomised clinical trial, consider a multivessel approach reasonable11 or recommend basing the revascularisation strategy on clinical status and comorbidities, as well as disease severity, according to the local Heart Team protocol12. In the largest observational study of non-ST-segment elevation acute coronary syndrome (NSTE-ACS) patients with multivessel disease, which compared a “culprit only” vs. a “complete” revascularisation strategy13, rates of in-hospital mortality, bleeding, renal failure and non-fatal cardiogenic shock were similar between the groups.

The aim of our study was to compare a “complete” vs. a “culprit only” revascularisation strategy in patients with myocardial infarction distinguishing the different clinical subsets (STEMI and NSTEMI), and to provide one-year clinical outcome from the “real-life” BleeMACS (Bleeding complications in a Multicenter registry of patients discharged with diagnosis of Acute Coronary Syndrome) registry.

Methods

The present study is a sub-analysis of the BleeMACS project. BleeMACS is an international multicentre investigator-initiated retrospective registry, without financial support, including 15,401 consecutive ACS patients undergoing PCI and discharged alive from 15 tertiary hospitals in Europe, Asia, North and South America (Germany, the Netherlands, Poland, Spain, Italy, Greece, Japan, China, Canada and Brazil). More details may be consulted in previous papers14, on the BleeMACS webpage (http://bleemacs.wix.com/registry), or at clinicaltrials.gov (Identifier: NCT02466854).

PATIENT SELECTION

All consecutive patients with multivessel coronary disease and a diagnosis of myocardial infarction (STEMI and NSTEMI) according to ESC guidelines12, treated with PCI during the index admission between 2003 and 2014, were eligible for inclusion. To be as consistent as possible with everyday clinical practice, no pre-specified exclusion criteria were stipulated.

Multivessel disease was defined as at least 70% diameter stenosis (50% for left main) of two or more epicardial coronary arteries or their major branches by visual estimation apart from the culprit lesion, with a diameter of at least 2.5 mm.

The culprit lesion was defined as the coronary stenosis related to presentation with ACS according to clinical, non-invasive instrumental data (electrocardiography, echocardiography) or invasive data (intravascular ultrasound or optical coherence tomography). These classifications were left to the operator’s discretion.

Patients were divided into two cohorts based upon the revascularisation strategy pursued at the time of presentation, either the incomplete revascularisation (IR) group if only the culprit lesion was treated by PCI, or the complete revascularisation (CR) group if a final angiography result without coronary stenosis ≥70% in major epicardial vessels or stenosis ≥50% in the left main was achieved. Complete revascularisation for STEMI patients was not performed during the index procedure but was staged, while for NSTEMI it was performed according to the operator’s discretion.

BASELINE CHARACTERISTICS

Baseline clinical features including age, burden of cardiovascular risk factors, presence of malignancy, history of previous bleeding, creatinine (md/dl) and haemoglobin (g/dl) were recorded.

Data concerning vascular access, number and type of stent (bare metal stent vs. drug-eluting stent vs. plain old balloon angioplasty) and thrombolysis were recorded.

Medications at discharge, including aspirin, choice of second antiplatelet (aspirin, clopidogrel, prasugrel and ticagrelor), use of beta-blockers, statins, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, and angiotensin receptor blockers at discharge were recorded.

ENDPOINT AND FOLLOW-UP

The primary endpoint was all-cause death at one year of follow-up. The secondary endpoints included in-hospital reinfarction, in-hospital heart failure, one-year myocardial infarction and one-year bleeding, and one-year MACE (the composite of one-year death and myocardial infarction). One-year bleedings were defined as any bleeding requiring hospitalisation.

The follow-up was clinical, performed through clinical visits, or phone call in the form of a formal query to primary care physicians.

STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

Continuous variables are expressed as mean±standard deviation (SD), and categorical variables as numbers and percentages (%). Correlations between parameters and study groups were tested in cross tabulation tables by means of the Pearson chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test for categorical variables and by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) for continuous variables.

Categorical variables were compared using Fisher’s exact test. Parametric distribution of continuous variables was tested graphically and with the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test, and the appropriate analyses were used according to the results. For propensity score matching, first logistic regression analysis was performed for all baseline features that differed between CR and IR groups at univariate analysis, stratified for admission diagnosis (STEMI and NSTEMI). Matching was computed after division into quintiles and using methods of nearest neighbour on the estimated propensity score15. Calibration was tested with the Hosmer-Lemeshow test, and accuracy was assessed with area under the curve analysis. Standardised differences were evaluated before and after matching to evaluate the performance of the model. All statistical analyses were performed with SPSS, Version 21 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA), and differences were considered significant at α=0.05.

Results

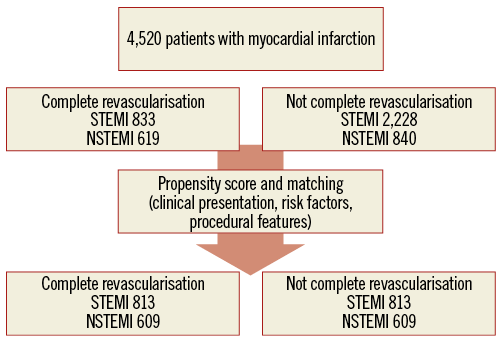

Among 15,401 patients in the BleeMACS registry, 4,520 (29.3%) presented with a diagnosis of multivessel myocardial infarction and were included in our analysis. The majority of patients presented with a diagnosis of STEMI (3,061; 67.7%), followed by NSTEMI (1,459; 32.3%) (Figure 1).

Figure 1. STEMI and NSTEMI patient distribution before and after propensity score-matching analysis.

STEMI SETTING

Eight hundred and thirty-three patients (27.2%) underwent complete coronary revascularisation (CR).

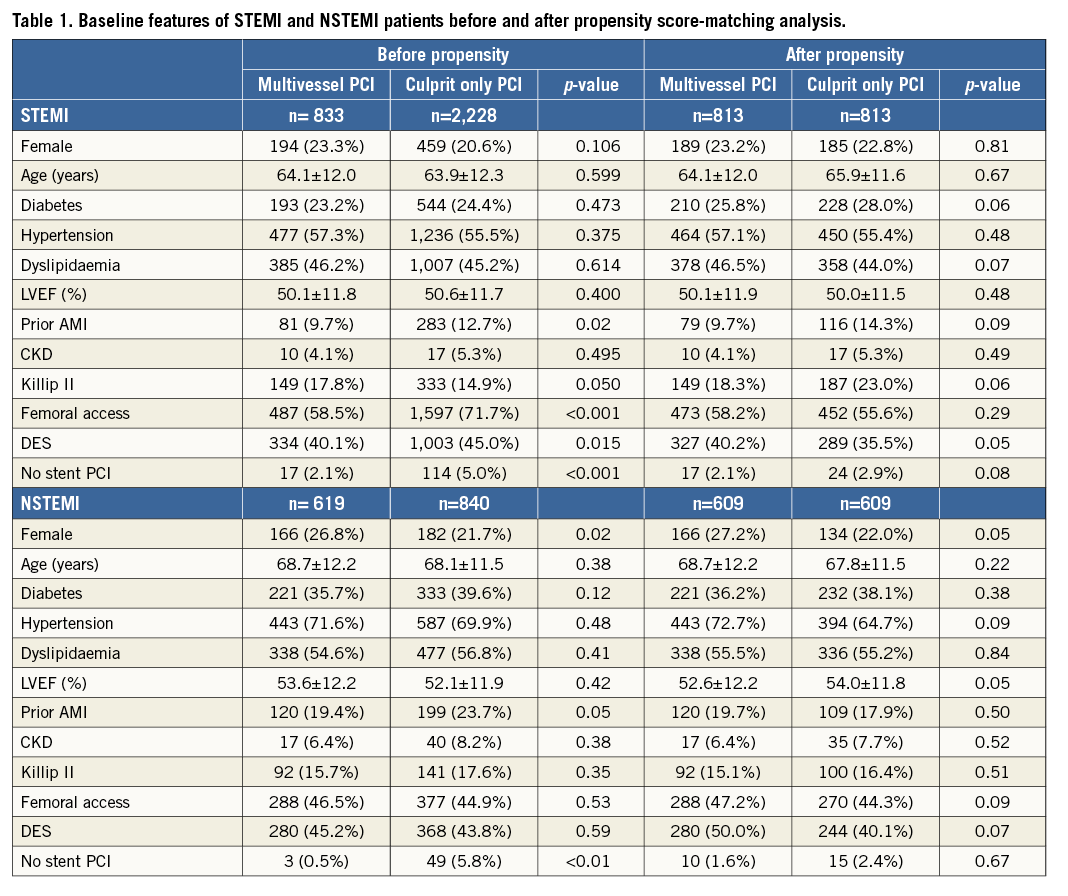

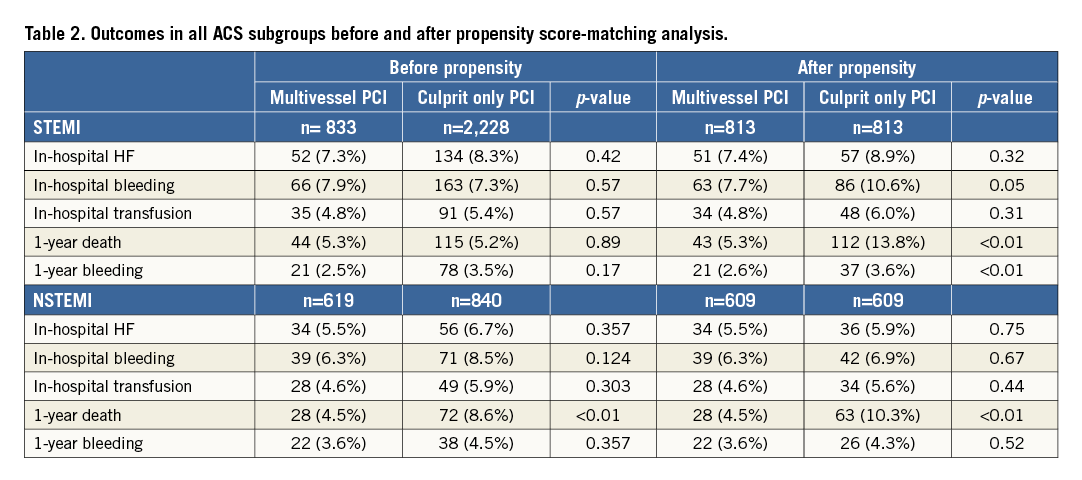

In the CR and IR groups, the percentage of female patients (23.3% vs. 20.6%; p=0.11), the age of patients (64.1±12.0 years vs. 63.9±12; p=0.60), and traditional risk factors were similar (all p-values >0.05). Fewer patients in the CR group had a history of previous myocardial infarction (9.7% vs. 12.7%; p=0.02) (Table 1). No differences were found between the two groups in terms of in-hospital outcomes (all p-values >0.05), one-year death rate (5.3% vs. 5.2%; p=0.89) and all secondary one-year outcomes (p-value >0.05 for all) (Table 2, Table 3).

After propensity score-matching analysis, 813 CR patients and 813 IR patients with similar baseline and procedural characteristics were selected. CR resulted in being superior in the prevention of one-year death (5.3% vs. 13.8%; p<0.01) and also in all the secondary one-year outcomes (p-value <0.05 for all) (Table 2, Table 3, Figure 2).

NSTEMI SETTING

Six hundred and nineteen patients (40.5%) underwent complete revascularisation (CR). The percentage of female patients undergoing CR was significantly higher than in those undergoing IR (26.8% vs. 21.7%; p=0.02). Traditional risk factors were comparable between the two groups (p-values >0.05 for all) (Table 1). The one-year death rate was reduced in CR patients (4.5% vs. 8.6%; p<0.01), as was the occurrence of one-year myocardial infarction (3.7% vs. 6.6%; p=0.02), and MACE (8.1% vs. 13.9%; p<0.01) (Table 2, Table 3).

The benefit of CR in NSTEMI patients was also confirmed after propensity score-matching analysis (Table 2, Table 3, Figure 2).

Figure 2. STEMI and NSTEMI patient outcomes after propensity score-matching analysis.

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this is one of the largest contemporary registries comparing complete and incomplete percutaneous revascularisation in all myocardial infarction subsets in patients presenting with multivessel coronary artery disease.

The main findings of this study are:

1. Rates of death, myocardial infarction and MACE at one-year follow-up were significantly lower in STEMI and NSTEMI patients undergoing CR compared to those undergoing IR.

2. CR was safe in both STEMI and NSTEMI patients, as proved by the similar rates of in-hospital and long-term bleeding.

Reperfusion strategies in patients with multivessel coronary disease are the subject of debate in the ACS setting, both in STEMI and in NSTE-ACS subgroups. The uncertainty about performing multivessel PCI in STEMI patients was reflected in an increased risk of periprocedural complications and long-term MACE in several publications exploring cardiovascular outcomes in the bare metal stent (BMS) and first-generation drug-eluting stent (DES) era16,17. Similarly, the absence of clinical benefit was described by Hassanin and colleagues in NSTE-ACS patients with multivessel disease18. Nevertheless, our results suggest a protective role in patients with myocardial infarction.

In STEMI patients, we reported that CR was superior to IR in terms of the one-year MACE rate. While the initial benefit of CR in STEMI patients appeared to be related only to a significant reduction in repeat PCI without any influence on the MACE rate19, the latest retrospective and prospective studies have shown a significant reduction of one-year MACE20. In particular, Wald and colleagues8 showed the benefit of preventive PCI in non-infarct arteries compared to a culprit only strategy. Their results were confirmed by a subsequent meta-analysis21,22.

Moreover, our analysis showed a significant reduction of myocardial infarction and death at 12-month follow-up in STEMI patients undergoing CR. These results are in accordance with those presented by a meta-analysis of four randomised trials23, in which a multivessel revascularisation strategy was associated with a significant reduction of all-cause death, cardiac death, recurrence of myocardial infarction and repeat revascularisation. However, the reduction of these hard endpoints was not achieved by the recent DANAMI-3—PRIMULTI trial24, in which more than 600 patients were randomised after “infarct-related PCI only” to either medical therapy or fractional flow reserve-guided complete revascularisation: the latter benefited in terms of a reduction of MACE driven by fewer repeat revascularisations, but the two groups did not differ in all-cause mortality or non-fatal reinfarction.

NSTEMI patients undergoing complete coronary revascularisation were shown to have a better one-year cardiovascular prognosis compared to IR patients. The one-year death, myocardial infarction and MACE rates were all reduced by a multivessel percutaneous strategy. On the other hand, primary and secondary outcomes were similar between unstable angina (UA) patients, regardless of the strategy of revascularisation. While the setting of multivessel disease in STEMI patients has been widely investigated, randomised trials comparing different revascularisation approaches in NSTE-ACS patients are lacking. Furthermore, most of the available studies have considered NSTEMI and UA as a single entity, with no risk stratification within the heterogeneous NSTE-ACS group. In this regard, a recent meta-analysis25 investigating the complete versus incomplete strategy in a miscellaneous NSTE-ACS population showed no clinical differences in terms of long-term mortality or myocardial infarction. Conversely, Onuma and colleagues26 showed a reduction of both MACE and myocardial infarction or death in “NSTEMI patients only” undergoing a complete revascularisation strategy, thus suggesting that a multivessel strategy could reduce hard endpoints, as also shown by our analysis. Consequently, the present paper stressed the importance of a complete revascularisation in NSTEMI patients.

Our results should encourage systematic risk stratification in the NSTE-ACS group, in order to define the PCI strategy better in this heterogeneous subset.

Finally, CR was safe in all the myocardial infarction subsets, as shown by the similar rates of in-hospital and long-term bleedings and by the need of transfusion between the two strategies; our results are consistent with those reported in both NSTE-ACS13 and STEMI8,24 studies.

Limitations

There are several limitations to our study, mainly concerning the observational design. First, the proportion of STEMI patients may reflect a selection of centres focused on primary PCI. Second, while propensity score matching may adjust for potential recorded confounders, it may not account for differences related to causality for unrecorded data, which may be avoided only by a randomised controlled trial. Moreover, the propensity score matching “selected” high-risk patients, as demonstrated by the reduction of sample size and by similar rates of death. Third, we chose a definition of non-culprit coronary stenosis of at least 70% by visual estimation in order to adhere as much as possible to clinical practice, despite a frequent use in the literature of a definition of stenosis as critical if more than 50%27,28. Moreover, the non-funded profile of our study led to an adherence to real-life clinical practice, although with some limitations regarding the absence of a central “core lab” to adjudicate events, in particular in-hospital death and recurrent MI. Data concerning interventional techniques, such as fractional flow reserve (FFR) (although largely debated in the ACS setting29), were not recorded, nor were those about the length of dual antiplatelet therapy30.

Despite the use of appropriate statistical adjustments, differences in patient baseline characteristics still remained. Moreover, since this is a subgroup analysis of the BleeMACS registry, specific variables (e.g., diagnosis of cardiogenic shock, drugs), procedural data (e.g., type of DES, treated and untreated vessels) and outcomes (e.g., post-procedural acute kidney disease, cardiac death), were not recorded. Finally, due to the absence of adjudication by a CEC and the heterogeneity of its definition, myocardial infarction and consequently MACE should be considered as softer endpoints.

Conclusions

This multicentre retrospective registry showed the benefit of a complete revascularisation strategy in terms of a reduction of one-year mortality in patients with myocardial infarction and multivessel coronary artery disease, suggesting that it is “better to do something rather than nothing”. Randomised controlled trials, including functional evaluation (FFR) of the lesions, especially in the NSTE-ACS setting, should be performed to confirm our results.

| Impact on daily practice A complete revascularisation strategy could be considered in both NSTEMI and STEMI patients with multivessel coronary disease because of its significant reduction of mortality compared to an incomplete strategy. |

Conflict of interest statement

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.