Abstract

The present study reveals that Election Day differentially affects the color preferences of US Republicans and Democrats. Voters’ preferences for Republican red and Democratic blue were assessed, along with several distractor colors, on and around the 2010 interim and 2012 presidential elections. On non-Election Days, Republicans and Democrats preferred Republican red equally, and Republicans actually preferred Democratic blue more than Democrats did. On Election Day, however, Republicans’ and Democrats’ color preferences changed to become more closely aligned with their own party’s colors. Republicans liked Republican red more than Democrats did, and no longer preferred Democratic blue more than Democrats did. These results are consistent with the hypothesis that color preferences are determined by people’s preferences for correspondingly colored objects/entities (Palmer & Schloss in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 107:8877–8882, 2010). They further suggest that color preferences are calculated at a given moment, depending on which color–object associations are currently most activated or salient. Color preferences are thus far more dynamic and context-dependent than has previously been believed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

On election night, millions of Americans watched US maps change color as voting results were broadcast on TV and the Internet. Little did they know that their color preferences were changing as well. Intense media discussion of “red states” and “blue states” leading up to 21st-century US elections leaves little doubt that politically knowledgeable Americans associate red with Republicans and blue with Democrats. Is it possible that those political associations with colors would affect voters’ color preferences?

Mounting empirical evidence suggests that color preferences are shaped by positive/negative experiences with correspondingly colored objects/entities (Palmer & Schloss, 2010; Schloss, Poggesi, & Palmer, 2011; Strauss, Schloss, & Palmer, 2013; Taylor & Franklin, 2012). These findings are consistent with the ecological valence theory’s (EVT’s) assumption that preference for a given color is determined by the combined preferences for all objects/entities associated with that color (Palmer & Schloss, 2010). Supporting the EVT, 80 % of the variance in average color preferences was explained by the weighted affective valence estimates (WAVEs) of 32 colors: the average positivity/negativity ratings of all objects that people associated with the colors, weighted by how well the colors matched the objects’ colors (Palmer & Schloss, 2010). Further evidence suggests that object preferences causally influence color preferences, because color preferences have been increased/decreased in the laboratory by experiences with positive/negative colored objects (Strauss et al., 2013). Furthermore, affiliation with rival universities (UC Berkeley and Stanford) has been found to influence preference for school colors: Students liked their own university’s colors more than their rivals did, to a degree that was positively correlated with self-reported school spirit (Schloss et al., 2011).

Exactly how experiences with characteristically colored objects/entities combine to produce color preferences is unknown. Does the brain maintain a running average of the valences (positive/negative feelings) of all previous experiences with a particular color? Do some experiences with colored objects weigh more heavily than others in the brain’s calculation of color preference? Does the impact of particular associations matter in some contexts more than others? The present study provides new insight into the dynamics of color preferences by suggesting that they are determined by the relative activation and strength of specific color–object associations at a given moment.

Previous findings about the color preferences of university students (Schloss et al., 2011) led to the hypothesis that Republicans might like red more than Democrats do, and that Democrats might like blue more than Republicans do. Positive affiliation with a political institution should lead to an overall preference for colors associated with that institution, as it had for universities. The present results reveal a more interesting, dynamic pattern, with preferences for party-consistent colors appearing only on Election Day.

Method

Participants

A total of 1,906 participants (247 in 2010; 1,659 in 2012), with a mean age of 33 years, took part in the study. Participants were classified as Republican/Democratic according to the percentages of times they reported having previously voted for Republican versus Democratic candidates. Participants who reported equal percentages for Republican and Democratic candidates were excluded (467/1,906 participants, 25 %), leaving a total of 1,439 participants. Participants were tested online using the Amazon Mechanical Turk (mTurk) and Qualtrics.Footnote 1 We did not assess color vision, because doing so online is nearly impossible. Moreover, we were interested in differences between the color preferences of Democrats and Republicans, regardless of whether they experienced colors with full trichromatic vision or weaker/deficient color vision. All participants gave informed consent, and the Committee for the Protection of Human Subjects approved the experimental protocol.

Design, displays, and procedure

The experiment title on mTurk was “Color Preference Experiment,” and politics was not mentioned until after participants had rated their color preferences. No information suggested that the experiment was related to Election Day or political parties until participants were directly asked about their political affiliation. It is therefore almost impossible that demand characteristics influenced the color preference judgments.

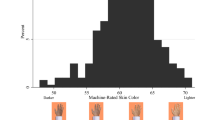

We tested 16 colors, including Republican red (Rep-red), Democratic blue (Dem-blue), and 14 fillers (see Fig. 1 and Table 1). The background was white (R:255/G:255/B:255). We based the RGB values for Rep-red and Dem-blue on the colors used on the official Republican and Democratic websites in 2010. We do not generally endorse specifying colors using device-dependent RGB values instead of device-independent coordinates (e.g., CIE 1931 xyY values), because this threatens the accuracy/replicability of color production across monitors. We made an exception for this study because forgoing rigorous calibration allowed us to test a broader sample of Democrats and Republicans than was available on the Berkeley campus, especially on Election Day. The fact that we obtained reliable group differences, despite variations in color rendering, attests to the robustness of the reported effects. Furthermore, people often experience Rep-red and Dem-blue on uncalibrated displays when viewing political websites and news articles on their computer monitors and when watching news coverage of political events on their televisions.

Participants were first shown the full 16-color array (Fig. 1, without labels) and asked to decide which colors they liked most and least, to anchor what liking “not at all” and “very much” meant for them in the context of these colors (Palmer, Schloss, & Sammartino, 2013). They proceeded to rate their preferences for colors, presented individually, using a slider scale from not at all to very much. Each trial contained text at the top of the screen, asking “How much do you like this color?” Below was a colored square ∼2.5 × 2.5 cm on a 1,440 × 900-pixel resolution, 13-in. monitor. Although the size of the colored squares varied according to each participant’s monitor size/resolution, the sizes of color patches on monitors have little impact on color preferences (Schloss, Strauss, & Palmer, 2013). Below the colored square was a slider scale whose left endpoint was labeled not at all (coded as −100), center point was labeled neutral (coded as 0), and right endpoint was labeled very much (coded as +100). The slider always started at “neutral” and had to be moved before participants could begin the next trial. After responding, participants clicked a “Continue” button. The colors were presented in random order.

After rating all 16 colors, participants were asked, “Considering only the elections in which you voted, in what % of them did you vote for candidates in the following political parties: Republican ___ and Democratic___” and filled in their estimates. Participants were classified as Republican, Democratic, or neither, depending on the party for which they voted more frequently.

At the end of the experiment, participants were presented with two reds (Rep-red and dark red), two blues (Dem-blue and dark blue), and four filler colors (light yellow, dark yellow, light green, and dark green) simultaneously arranged in a vertical column. First they rated how strongly they associated each color with the Democratic Party on a slider scale (scored from 0 to 10) to the right of each color. They then repeated this procedure for the Republican Party.

Results and discussion

Color preferences of Republicans and Democrats

The data from the 2010 US election season showed no overall difference in Republicans’ and Democrats’ preferences for Rep-red or Dem-blue (Fs < 1) (see Figs. 5a–c in the Appendix for the data and numbers of participants in the groups). Because we had expected overall group differences analogous to Schloss et al.’s (2011) finding that school affiliation influenced color preferences for Berkeley and Stanford students, we initially concluded that those results did not generalize to political affiliations.

Closer inspection revealed that the effects of political affiliation on color preferences were more dynamic and context-dependent than we had anticipated. On Election Day (Nov. 2), Republicans tended to like Republican red more than Democrats did, and Democrats tended to like Democratic blue more than Republicans did, as initially expected. In contrast, participants tended to show the opposite pattern of preferences on non-Election Days. Unfortunately, the sample included too few participants for this temporal difference to reach statistical significance (see Appendix). We therefore waited until the 2012 election to accumulate more data.

In 2012, we repeated the same procedure as in 2010, collecting data during the weeks preceding the election, on Election Day (Nov. 6), and over the following weeks. We only included participants who had unique IP addresses, to eliminate data sets from previous participants. We combined the 2010 and 2012 data because a four-way analysis of variance (Year × Color × Timing × Party Affiliation) indicated that year did not interact with overall preference for red versus blue, and that none of the higher-order interactions were significant (Fs < 1.05). (See Figs. 5d–f in the Appendix for the 2012 data.)

Participants generally preferred blue to red [F(1, 1438) = 15.33, p < . 001, η 2 = .01] (Figs. 2a–b), as had been found previously in nonpolitical contexts (Eysenck, 1941; Guilford & Smith, 1959; McManus, Jones, & Cottrell, 1981; Palmer & Schloss, 2010). However, we found a significant three-way interaction among color (red/blue), political affiliation (Democratic/Republican), and timing (Election Day/non-Election Day) [F(1, 1431) = 7.07, p < .01, η 2 = .005]. On Election Day, Republicans liked Rep-red more than Democrats did [F(1, 93) = 7.03, p < .01, η 2 = .07], but there was no corresponding party difference in preferences for Rep-red on non-Election days (F < 1; Fig. 2a). The pattern of preferences for Dem-blue was less straightforward, but still consistent with the pattern that color preferences were more party-consistent on Election Day than on other days (Fig. 2b). On non-Election days, Republicans liked Dem-blue more than Democrats did [F(1, 1342) = 16.45, p < .001, η 2 = .01]. Possible explanations for this initially puzzling result will be discussed below. This difference diminished on Election Day (F < 1), when Democrats tended to like blue somewhat more, and Republicans tended to like it somewhat less than on non-Election baseline days.

Color preferences of Republicans (gray bars) versus Democrats (white bars). (a) Preferences for Republican red on non-Election versus Election Days. (b) Preferences for Democratic blue on non-Election versus Election Days. (c) Preferences for Republican red and Democratic blue on Election Day minus non-Election Days (baseline). Positive difference scores indicate greater preference on Election Day, and negative ones indicate lesser preference on Election Day. The numbers of participants in different groups are displayed in parentheses, and error bars represent standard errors of the means

Figure 2c shows (signed) changes in preference for Rep-red and Dem-blue on Election Day relative to baseline, by subtracting out the corresponding baseline preferences on non-Election Days. Republicans like Rep-red and dislike Dem-blue more on Election Day than on non-Election Days, and Democrats like Dem-blue and dislike Rep-red more on Election Day than on non-Election Days. Although the only change from baseline that reached statistical significance was Republicans’ increase in preference for Rep-red [F(1, 419) = 3.95, p < .05, η 2 = .009], all four difference scores were in the predicted directions (p = .0625 by a sign test). The corresponding difference scores showed the same pattern in 2010 and 2012 (Appendix), with eight out of eight differences being in the predicted directions (p < .01 by a sign test). These results are consistent with the notion that people do not simply judge color preference from a stored average valence for all experiences with a particular color, but rather compute them on the fly, on the basis of which color associates are currently activated. We will discuss this issue further below.

Evidence for an “underdog effect”

One perplexing aspect of the color preference data is the asymmetry between Republicans’ and Democrats’ preference changes for party colors on Election Day: The Republican increase in liking red was reliably greater than the Democratic increase in liking blue (Fig. 2c). This asymmetry may be due to an “underdog effect,” in which members of the party expected to lose the election feel stronger group affiliation from pulling for their party to rally, as compared with members of the party expected to win. This hypothesis is consistent with social threat cohesion, in which group identity strengthens when group members feel threatened (e.g., Smeekes & Verkuyten, 2013; Turner, Hogg, Turner, & Smith, 1984). In the 2012 election, from which the majority of the data come, Republicans were underdogs because they were predicted to lose seats in Congress and their presidential candidate was predicted to lose to the incumbent Democratic president. In contrast, Democrats were relatively confident that their candidates would win and were less emotionally uncertain about the outcome of the election. This underdog effect may also be related to asymmetries in the color preferences of Berkeley and Stanford students reported in Schloss et al. (2011). The hypothesis that an underdog effect biases color preferences suggests interesting and testable predictions about how personal investment or striving on behalf of a color-related socio-political institution modulates color preferences in rivalrous situations.

Explaining dynamic color preferences

Why are color preferences more consistent with party affiliations on Election Day than on non-Election Days? An EVT-based explanation is that the mechanisms underlying color preference include a dynamic activation component. The degree to which preference for a particular object or entity influences preference for a specific color may depend on at least two factors at the moment that the color preference judgment is made: (1) the overall activation of the object/entity in memory, and (2) the strength and specificity of the object’s/entity’s color associations.

In the present study, the first factor concerns the relative activation of political parties, as compared with those of all other objects/entities in memory associated with red and blue. To illustrate, assume that a fixed set of objects/entities are red and a fixed set are blue, and that the combined preferences those objects/entities contribute to preferences for red and blue, respectively. If activation of a specific red entity (the Republican Party) and/or a blue entity (the Democratic Party) is heightened on Election Day, then those associations will have a greater impact on preferences for red and/or blue than if they were less activated. Although those associations still exist on non-Election Days, their activation would be weaker, and other, more salient objects would influence color preferences more strongly (e.g., during a berry-picking outing, preferences for strawberries and blueberries would likely be more salient). This notion of differential activation is consistent with the hypothesis that context strongly biases the associations that people have with colors (Elliot & Maier, 2012). Although we report no direct evidence for this activation hypothesis here, previous results have indicated that activating specific color–object associations biases color preferences, at least for a limited period of time (Strauss et al., 2013). Furthermore, it seems plausible that most American voters are more cognizant of their party affiliation on Election Day than on other days, except perhaps for diehard political advocates, for whom party issues are omnipresent.

The second factor concerns the strength and specificity of party–color associations. If an object is only weakly associated with a color, then it may have less impact on preference for that color. This can be true even if an object is strongly activated. For example, the sky is strongly activated while sunbathing at the beach, but it has little impact on preference for purple, because purple is only weakly associated with the sky. Indeed, the object–color match weighting factor in Palmer and Schloss’s (2010) WAVE measure was designed to estimate such differences in association strength when predicting color preferences. Concerning specificity, if an object is associated with multiple colors, then preference for that object will impact the preferences for all associated colors. If Republicans associate the Republican Party with both red and blue, then positive affect for the Republican Party should influence preferences for both red and blue, though to different degrees reflecting the relative strengths of those associations. It makes sense that party colors would be more ecologically evident on Election Day, given the prevalence of color-coded media maps. If party–color associations are stronger and/or more specific on Election Day than on non-Election Days, that might account for changes in color preferences.

We investigated this possibility by analyzing participants’ ratings of how strongly they associated each color with the Republican and Democratic parties. Averaged over all Republican and Democratic participants, Rep-red was most strongly associated with the Republican Party, and Dem-blue was most strongly associated with the Democratic Party (Fig. 3). Rep-red was even more strongly associated with the Republican Party than was dark red [F(1, 1438) = 653.63, p < .001, η 2 = .31], and Dem-blue was more strongly associated with the Democratic Party than was dark blue [t(1438) = 162.22, p < .001, η 2 = .10]. However, party–color associations were more accurate on Election Day (Fig. 4), and the ways in which they were less accurate on non-Election Days can partly explain the color preference pattern in Fig. 2.

Ratings of party–color association strengths for the Republican and Democratic parties. Error bars represent standard errors of the means. The colors along the x-axes represent Republican red (Rep-red), dark red (DR), dark yellow (DY), light yellow (LY), dark green (DG), light green (LG), dark blue (SB), and Democratic blue (Dem-blue)

Party–color associations of Republicans (gray bars) versus Democrats (white bars). (a) Associations between the Republican Party and Republican red on non-Election versus Election Days. (b) Associations between the Republican Party and Democratic blue on non-Election versus Election Days. (c) Associations between the Democratic Party and Republican red on non-Election versus Election Days. (d) Associations between the Democratic Party and Democratic blue on non-Election versus Election Days. The numbers of participants in different groups are displayed in parentheses. Error bars represent standard errors of the means

Averaged over all participants, color association ratings for the correct color pairings (Republican Party with Rep-red, Democratic Party with Dem-blue) were equally strong on Election Day and non-Election Days (Fs < 1; see Fig. 4). Color association ratings for the incorrect pairings were lower, and thus more accurate, on Election Day than on non-Election Days: the Republican Party with Dem-blue, F(1, 1437) = 4.52, p < .05, η 2 = .003, and the Democratic Party with Rep-red, F(1, 1437) = 9.21, p < .01, η 2 = .006. These results suggest that party–color associations are indeed more specific on Election Day. People have nonnegligible baseline associations between the Republican Party and blue and between the Democratic Party and red that are less evident on Election Day, when party–color associations are particularly apparent. We will return below to why these default biases may exist.

The party association data on non-Election Days revealed patterns that are consistent with two surprising aspects of the preference data: (1) Republicans and Democrats liked red equally (Fig. 2a) and (2) Republicans liked blue more than Democrats did (Fig. 2b). As compared with Democrats, Republicans not only had a weaker association between red and the Republican Party [F(1, 1342) = 6.16, p < .05, η 2 = .005; Fig. 4a], but also a marginally stronger association between red and the Democratic Party [F(1, 1342) = 3.77, p = .052, η 2 = .003; Fig. 4c]. The combination of associating red less with their own party and more with their rival party implies weaker and less specific associations with red, which may have contributed to Republicans not liking red more than Democrats did on non-Election Days. A similar story holds for blue. As compared with Democrats, Republicans associated blue more strongly with the Republican Party [F(1, 1342) = 42.08, p < .001, η 2 = .03; Fig. 4b] and less strongly with the Democratic Party [F(1, 1342) = 68.86, p < .001, η 2 = .05; Fig. 4d]. These differences relative to Democrats’ associations may have contributed to the higher Republican preference for blue on non-Election Days. As with red, Republicans’ associations with blue were weaker and less specific than those of Democrats. Such weaker, less specific associations may have prevented positive affect toward the Republican Party from selectively having a positive impact on preference for red and a negative impact on preference for blue. However, the association data do not fully explain political effects on color preferences, because affiliates of both parties still associated blue more strongly with the Democratic Party than with the Republican Party, and red much more strongly with the Republican Party than with the Democratic Party on both non-Election and Election Days (all Fs > 15, ps < .001, η 2s > .41).

Explaining party–color association biases on non-Election Days

Finally, we return to the question of why people show tendencies toward associating the Republican Party with blue and the Democratic Party with red on non-Election days, despite the opposite media-defined party–color assignments in the US. One possibility is the influence of default meanings of the colors (Elliot & Maier, 2012). For example, red is considered to be relatively aggressive, and blue to be relatively calm and passive (e.g., Kaya & Epps, 2004; Palmer, Schloss, Xu, & Prado-León, 2013). People may have a default bias to associate Republicans more with blue than with red because conservatives are generally more threat-averse and conflict-avoidant than liberals (Jost & Amodio, 2012). Converging support for this difference between conservatives and liberals comes from psychological (Jost, Glaser, Kruglanski, & Sulloway, 2003), physiological (Oxley et al., 2008), neuropsychological (Amodio, Jost, Master, & Yee, 2007), and neuroanatomical (Kanai, Feilden, Firth, & Rees, 2011) evidence.

Other possible influences concern cultural and historical factors in the political associations of colors. In many parts of the world, more-liberal parties are associated with red and more-conservative parties with blue (Bensen, 2004; Enda, 2012; Farhi, 2004). Indeed, before the year 2000, US party–color assignments varied from election to election, and the opposite of the contemporary party colors tended to be used: blue for Republicans and red for Democrats. For example, when Republican Reagan swept the 1984 presidential election, the election map coded Regan victories in blue and was referred to as a “suburban swimming pool” (Enda, 2012).

How might default and contemporary party–color associations have combined to produce changes in color preferences on Election Day relative to non-Election Days? We believe that both types of associations contribute to color preferences to some extent, all of the time. However, the default meanings and deeply ingrained associations held on non-Election Days were overridden on Election Day, when people carefully monitored election map colors in the media. This change was evident in our participants’ party–color associations. As media-based experiences reinforced the new canonical color associations on Election Day, people’s color preferences became more aligned with their affiliated party’s canonical colors. Perhaps in several years, when the notions of conservative “Red States” and liberal “Blue States” becomes even more deeply embedded in the US political consciousness, party-consistent color preferences will become a more persistent norm.

Notes

Perception and cognition experiments conducted online have produced results comparable to the same experiments conducted in traditional laboratory settings (Germine et al., 2012).

References

Amodio, D. M., Jost, J. T., Master, S. L., & Yee, C. M. (2007). Neurocognitive correlates of liberalism and conservatism. Nature Neuroscience, 10, 1246–1247. doi:10.1038/nn1979

Bensen, C. (2004). Red state blues: Did I miss that memo? (Technical Report). Lake Ridge, VA: POLIDATA Political Data Analysis. Retrieved from www.polidata.org/elections/red_states_blues_de27a.pdf

Elliot, A., & Maier, M. A. (2012). Color-in-context theory. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, 45, 63–125.

Enda, J. (2012, Nov 1). When Republicans were blue and Democrats were red. Retrieved from Smithsonian.com.

Eysenck, H. J. (1941). A critical and experimental study of color preference. American Journal of Psychology, 54, 385–391.

Farhi, P. (2004, Nov 2). Elephants are red, donkeys are blue; color is sweet, so their states we hue. The Washington Post. Retrieved from www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/articles/A17079-2004 Nov1.html

Germine, L., Nakayama, K., Duchaine, B. C., Chabris, C. F., Chatterjee, G., & Wilmer, J. B. (2012). Is the Web as good as the lab? Comparable performance from Web and lab in cognitive/perceptual experiments. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review, 19, 847–857. doi:10.3758/s13423-012-0296-9

Guilford, J. P., & Smith, P. C. (1959). A system of color-preferences. American Journal of Psychology, 72, 487–502.

Jost, J. T., & Amodio, D. M. (2012). Political ideology as motivated social cognition: Behavioral and neuroscientific evidence. Motivation and Emotion, 36, 55–64. doi:10.1007/s11031-011-9260-7

Jost, J. T., Glaser, J., Kruglanski, A. W., & Sulloway, F. J. (2003). Political conservatism as motivated social cognition. Psychological Bulletin, 129, 339–375. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.129.3.339

Kanai, R., Feilden, T., Firth, C., & Rees, G. (2011). Political orientations are correlated with brain structure in young adults. Current Biology, 21, 677–680. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2011.03.017

Kaya, N., & Epps, H. H. (2004). Relationship between color and emotion: A study of college students. College Student Journal, 38, 396–405.

McManus, I. C., Jones, A. L., & Cottrell, J. (1981). The aesthetics of colour. Perception, 10, 651–666.

Oxley, D. R., Smith, K. B., Alford, J. R., Hibbing, M. V., Miller, J. L., Scalora, M., & Hibbing, J. R. (2008). Political attitudes vary with physiological traits. Science, 321, 1667–1670.

Palmer, S. E., & Schloss, K. B. (2010). An ecological valence theory of human color preference. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 107, 8877–8882. doi:10.1073/pnas.0906172107

Palmer, S. E., Schloss, K. B., & Sammartino, J. (2013a). Visual aesthetics and human preference. Annual Review of Psychology, 64, 77–107. doi:10.1146/annurev-psych-120710-100504

Palmer, S. E., Schloss, K. B., Xu, Z. X., & Prado-León, L. R. (2013b). Music–color associations are mediated by emotion. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 110, 8836–8841.

Schloss, K. B., Poggesi, R. M., & Palmer, S. E. (2011). Effects of university affiliation and “school spirit” on color preferences: Berkeley versus Stanford. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review, 18, 498–504. doi:10.3758/s13423-011-0073-1

Schloss, K. B., Strauss, E. D., & Palmer, S. E. (2013). Object color preferences. Color Research and Application, 38, 393–411.

Smeekes, A., & Verkuyten, M. (2013). Collective self-continuity, group identification and in-group defense. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 49, 984–994.

Strauss, E. D., Schloss, K. B., & Palmer, S. E. (2013). Color preferences change after experience with liked/disliked colored objects. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review, 20, 935–943. doi:10.3758/s13423-013-0423-2

Taylor, C., & Franklin, A. (2012). The relationship between color–object associations and color preference: Further investigation of ecological valence theory. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review, 19, 190–197. doi:10.3758/s13423-012-0222-1

Turner, J. C., Hogg, M. A., Turner, P. J., & Smith, P. (1984). Failure and defeat as determinants of group cohesiveness. British Journal of Social Psychology, 23, 97–111.

Author Note

We thank Joseph Austerweil, Bill Prinzmetal, and Melissa Ferguson for insightful discussions and Mathilde Heinemann for help with preliminary analyses. This work was supported by the National Science Foundation (Grant Nos. BCS-1059088 and BCS-0745820).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix: Party color preferences, separated by year

Appendix: Party color preferences, separated by year

Figure 5 shows Democrats’ and Republicans’ preferences for Republican red (Figs. 5a and d) and Democratic blue (Figs. 5b and e), separated by year (2010 and 2012). In 2010, members of each party tended to prefer their own colors on Election Day and the opposite colors on non-Election Days, but too few participants were sampled on Election Day for this three-way interaction to reach statistical significance [F(1, 176) = 3.04, p = .08, η 2 = .02].

Color preferences of Republicans (gray bars) versus Democrats (white bars). The top row shows (a) preferences for Republican red on non-Election and Election Days, (b) preferences for Democratic blue on non-Election and Election Days, and (c) preferences for both Republican red and Democratic blue on Election Day minus non-Election Days (baseline), from 2010. The bottom row (panels d–f) shows the corresponding data from 2012. The large error bars in the 2010 data are largely due to the small sample sizes. The numbers of participants in different groups are displayed in parentheses, and error bars represent standard errors of the means

For 2012, we found a reliable Color × Party × Timing three-way interaction [F(1, 1255) = 4.63, p < .05, η 2 = .004]. On Election Day itself, Republicans liked Republican red more than Democrats did [F(1, 80) = 6.69, p < .05, η 2 = .08], but no party difference was apparent in preferences for Republican red on non-Election Days [F(1, 1175) = 1.80, p = .18, η 2 = .002] (Fig. 5d). The pattern of preferences for Democratic blue was also consistent with the hypothesis that color preferences are more party-consistent on Election Day than on other days (Fig. 5e). On non-Election Days, Republicans liked Democratic blue more than Democrats did [F(1, 1175) = 16.17, p < .001, η 2 = .01], and this reverse party color difference diminished on Election Day (F < 1).

Figures 5c and f show preferences for Republican red and Democratic blue on Election Day, after subtracting out the respective baselines of non-Election Day preferences in 2010 and 2012. All eight difference scores were in the predicted direction (binomial sign test p < .01), with Republicans liking Republican red and disliking Democratic blue more on Election Day than on non-Election Days, and Democrats liking Democratic blue and disliking Republican red more on Election Day than on non-Election Days in both 2010 and 2012. However, the only change from baseline that reached statistical significances was Republicans’ increase in preference for Republican red in 2012 [F(1, 362) = 4.32, p < .05, η 2 = .01].

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Schloss, K.B., Palmer, S.E. The politics of color: Preferences for Republican red versus Democratic blue. Psychon Bull Rev 21, 1481–1488 (2014). https://doi.org/10.3758/s13423-014-0635-0

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.3758/s13423-014-0635-0