Published online Jul 7, 2021. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v27.i25.3901

Peer-review started: February 5, 2021

First decision: March 14, 2021

Revised: March 27, 2021

Accepted: May 21, 2021

Article in press: May 21, 2021

Published online: July 7, 2021

The proportion of young patients with colorectal cancer (CRC), especially in their 40s, is increasing worldwide.

To confirm the clinical characteristics of such patients, we planned a study comparing them to patients in their 30s and 50s.

Patients undergoing primary resection for CRC, patients in their 30s, 40s and 50s were included in the study. Patient and tumor characteristics, and perioperative and oncologic outcomes were compared.

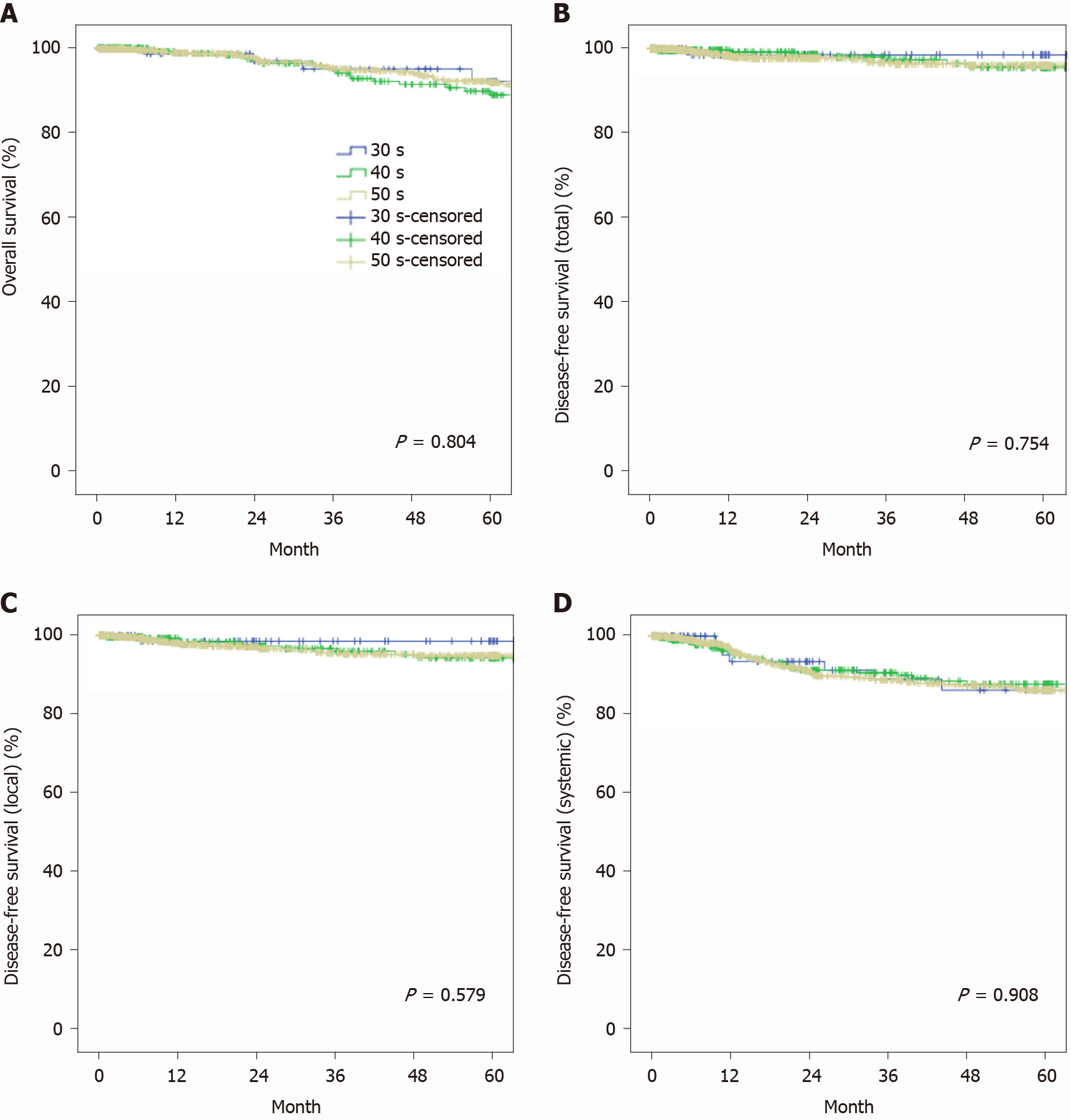

Most clinical characteristics of 451 (10.5%) patients in their 40s were more similar to those of patients in their 30s than those in their 50s. On pathology data, there were more metastatic lesions (30s vs 40s vs 50s; 17.5% vs 21.1% vs 14.9%, P = 0.012) in patients in their 40s. There was a trend toward less frequent K-ras mutations among patients in their 40s (48.5% vs 33.3% vs 44.5%, P = 0.064). The proportion of patients receiving postoperative chemotherapy was also significantly greater among patients in their 40s (58.3% vs 63.9% vs 56.3%, P = 0.032). Five-year overall survival (OS) and disease-free survival (DFS) did not differ between the three groups (5-year OS, 92.2% vs 89.8% vs 92.2%, P = 0.804; 5-year total DFS, 98.6% vs 95.7% vs 96.1%, P = 0.754; 5-year local DFS, 98.6% vs 94.3% vs 94.9%, P = 0.579; 5-year systemic DFS, 86.4% vs 87.9 % vs 86.4%, P = 0.908).

Patients with CRC in their 40s showed significantly more numerous metastatic lesions. The oncologic outcome of stage 1-3 patients in their 40s was not inferior compared to that of those in their 30s and 50s.

Core Tip: The age at which colorectal cancer is first diagnosed is decreasing worldwide, and colorectal cancer, especially in the 40s is very important. In our study, we found that colorectal cancer patients in their 40s had significantly more metastatic lesions and fewer K-ras mutations. Nevertheless, the oncologic outcome was never inferior compared to patients in their 30s and 50s by stages. We believe this to be a very important clinical message in the current situation.

- Citation: Lee CS, Baek SJ, Kwak JM, Kim J, Kim SH. Clinical characteristics of patients in their forties who underwent surgical resection for colorectal cancer in Korea. World J Gastroenterol 2021; 27(25): 3901-3912

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v27/i25/3901.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v27.i25.3901

Because colorectal cancer (CRC) is the third most common cancer in the world and the second most common cancer in Korea, it is a health-sociologically important cancer. The epidemiology of CRC (incidence, age distribution of CRC, etc.) varies greatly among different countries and races. In Korea, the proportion of CRC patients under the age of 50 is among the highest in the world. Based on the annual report of cancer statistics in Korea, of the 25881 patients diagnosed with newly developed CRC in 2019, about 10% were patients under 50[1]. Not only is the proportion of young patients high in Korea, but the rate of increase is also very rapid both in Korea and worldwide[2-7]. In the United States, data gathered over the past 40 years confirms the proportion of young CRC patients has increased gradually, mainly among patients in their 40s, and especially among African-American and Hispanic patients[8,9]. A previous study explained that the recent increase in young colorectal cancer patients is related with changes to Western style diet, in lifestyle, and an increase in environmental carcinogens[10].

Amid the global trend of increasing proportion and importance of young patients with CRC, clinical characterization of CRC patients in their 40s is somewhat unique. Patients with colorectal cancer in their 40s have the potential for both late-onset hereditary CRC and early-onset sporadic CRC. Patients in their 40s have lived long enough to be exposed to environmental carcinogens and they are in the age group where sporadic CRC can develop. However, the possibility of hereditary CRC cannot be excluded in this group, as it is relatively young compared to the average age of CRC. In hereditary CRC, genetic counseling, including somatic mutation testing, is important. However, in countries with many young CRC patients, such as Korea, genetic counseling for all patients in their 40s is not available and is not cost effective. In addition, there are secondary problems that are sometimes overlooked even in patients who need to be examined genetic testing[11].

Whatever the cause, the recent rapid increase in number of young CRC patients is a socially important issue. In particular, young people have an important socioeconomic role, so the increase in young CRC patients is directly linked to socioeconomic problems. Therefore, it is very important to understand and actively manage the characteristics of these patients. However, few studies have analyzed the characteristics of patients with CRC in their forties[12-14]. Therefore, we planned to determine the proportion of patients in their 40s with CRC and to identify their clinical characteristics, especially compared with those in their 30s and 50s, and to develop a manage

Among the 4326 patients with CRC who underwent primary resection in our hospital from September 2006 to July 2019, patients in their 30s, 40s, and 50s were included in the study. Only primary pathologically confirmed adenocarcinomas located in the area from the appendix to the rectum were included in the study. Patients who had only diversion without resection, or who had recurrent cancer or metastases of other cancers were excluded from the study. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Korea University Anam Hospital (No. 2020AN0309) and all participants provided informed consent.

In this study, cancers of the appendix, cecum, and ascending, hepatic flexure, and transverse colon were classified as right-sided colon cancer, while cancers of the splenic flexure, descending, and sigmoid colon were classified as left-sided colon cancer, and cancers of the rectosigmoid colon were classified as rectal cancer. In our institution, most surgeries have been performed minimally invasively since 2006. In addition, D3 Lymphadenectomy is routinely performed in radical operations for all CRCs. The types of surgical procedure were so diverse that they were classified into lesional radical operations (including complete mesocolic excision or total mesorectal excision), total surgery (total abdominal colectomy or total proctocolectomy), and limited surgery. In rare cases, two or more segmental colectomies were performed simultaneously.

Our institution conducts perioperative evaluation and treatment based on the National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines. All patients with colon cancer had been evaluated preoperatively by physical examination, total colonoscopy, abdominopelvic computed tomography (CT), chest CT, and routine laboratory testing, which included tests for tumor markers. If necessary, additional tests, such as rectal magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), liver MRI, and positron emission tomography-CT, were performed. If necessary, stent insertion or neoadjuvant chemotherapy or radiotherapy were performed before surgery. When surgery was performed in an emergency, studies that were not evaluated before surgery were performed as soon as possible after surgery. If there were no problems after surgery, water intake was allowed the day after surgery and a soft diet started on the second day after surgery. After surgery, adjuvant treatment was performed as appropriate considering the stage of cancer, the patient's age, general condition, and socioeconomic status. After adjuvant treatment, follow-up examinations were carried out at 3-mo intervals during the first 2 years postoperatively, at 6-mo intervals until 5 years after surgery, and then annually if there was no evidence of recurrence.

Patients were divided into three groups comprising patients in their 30s, 40s, or 50s to compare patient and tumor characteristics, perioperative data, and oncologic outcomes. Descriptive results were presented as the mean or median for continuous outcomes and as frequency or percentage for categorical outcomes. For comparison between two groups, Student's t-tests were used to compare continuous variables, and the χ2 test or Fisher's exact test was applied for categorical variables. ANOVA was used to compare the three groups. Five-year overall survival (OS) and disease-free survival (DFS) were analyzed using the Kaplan-Meier method. Statistical analyses was performed using SPSS® version 22.0 (IBM, Armonk, NY, United States). A P value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

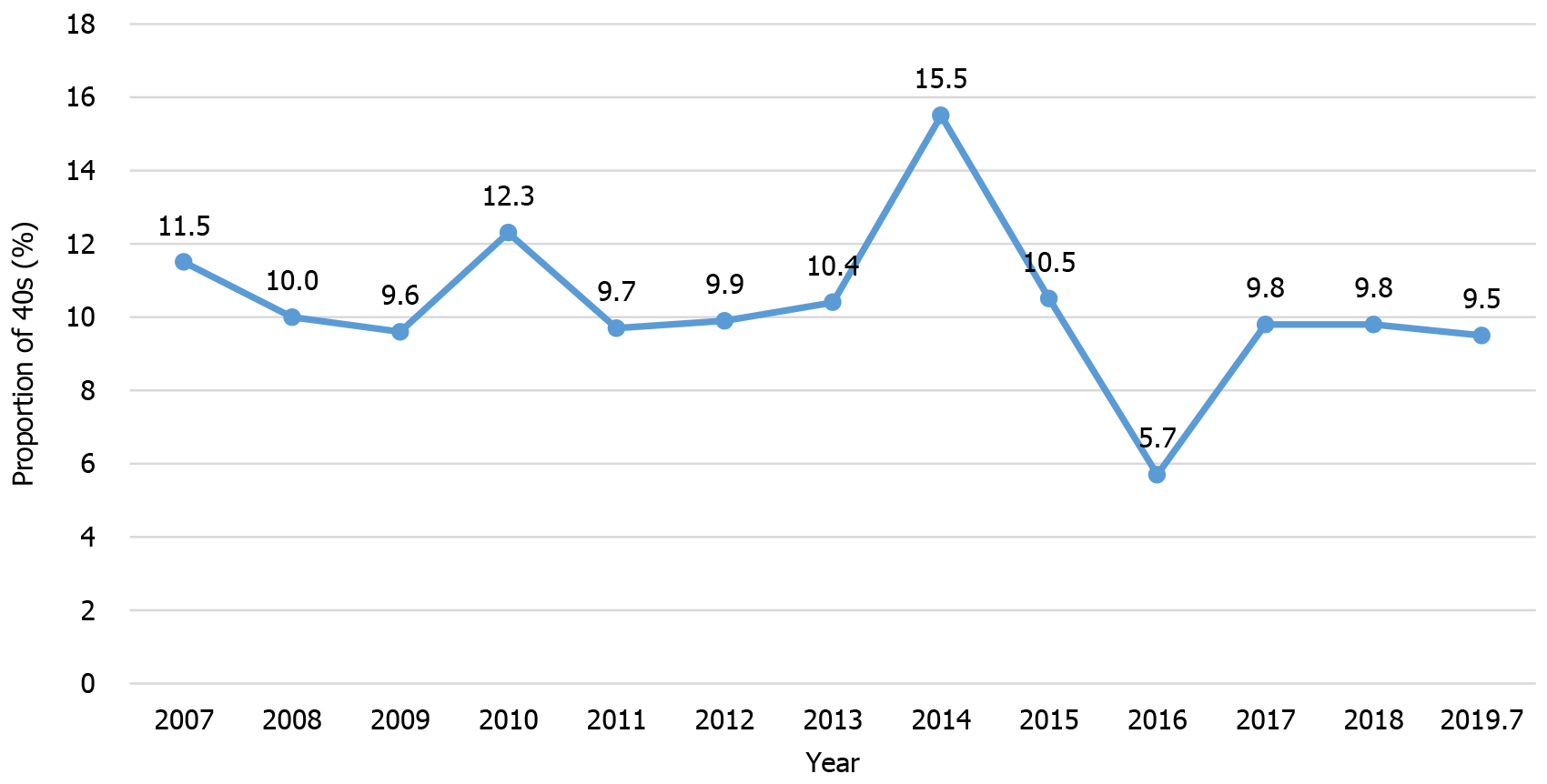

Of the 4326 patients included in the study, 120 were in their 30s (2.8%), 451 were in their 40s (10.5%), and 1044 were in their 50s (24.4%). The proportion of patients in their 40s did not significantly increase or decrease over time (Figure 1). Compared to those in their 30s and 40s, the proportion of men among patients in their 50s was greater (55.0% vs 56.8% vs 65.7%, P = 0.001) (Table 1). There were significant co-morbidities among patients in their 50s, especially cardiovascular diseases (2.5% vs 11.8% vs 29.8%, P < 0.001), and endocrine disorders, including diabetes mellitus (3.3% vs 9.5% vs 14.3%, P < 0.001), and the American Society of Anesthesiologists score was also high (P < 0.001). Body mass index was also greater among patients in their 50s (23.2 vs 23.3 vs 23.7 kg/m2, P = 0.049). Tumor location, preoperative carcinoembryonic antigen, carbohydrate antigen 19-9 Level, preoperative complications and treatment did not differ between the three groups, but more neoadjuvant treatments were performed in patients in their 30s and 40s (26.7% vs 25.5% vs 15.3%, P < 0.001).

| 30s (n = 120) | 40s (n = 451) | 50s (n = 1044) | P value1 | P value2 | P value3 | P value4 | |

| Sex, male (%) | 55.0 | 56.8 | 65.7 | 0.730 | 0.001 | 0.020 | 0.001 |

| Co-morbidity (%) | 28.3 | 37.3 | 52.9 | 0.070 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 |

| Endocrine | 3.3 | 9.5 | 14.3 | 0.028 | 0.012 | 0.001 | < 0.001 |

| CVD | 2.5 | 11.8 | 29.8 | 0.002 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 |

| Pulmonary | 5.8 | 3.5 | 6.3 | 0.259 | 0.031 | 0.835 | 0.096 |

| Other | 20.8 | 21.1 | 20.6 | 0.956 | 0.837 | 0.951 | 0.979 |

| ASA score (%) | 0.079 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | |||

| 1 | 47.5 | 40.8 | 30.4 | ||||

| 2 | 50.8 | 56.3 | 66.3 | ||||

| 3 | 0 | 2.0 | 2.4 | ||||

| 4 | 0 | 0.2 | 0.1 | ||||

| 5 | 0 | 0 | 0.1 | ||||

| Unknown | 0.8 | 0.7 | 0.8 | ||||

| BMI, mean (kg/m2) | 23.2 | 23.3 | 23.7 | 0.899 | 0.023 | 0.143 | 0.049 |

| Tumor location (%) | 0.975 | 0.061 | 0.268 | 0.126 | |||

| Right-sided colon | 20.0 | 16.0 | 20.9 | ||||

| Left-sided colon | 21.7 | 29.0 | 27.7 | ||||

| Rectum | 55.8 | 53.4 | 50.0 | ||||

| Multiple | 2.5 | 1.6 | 1.5 | ||||

| CEA, median (ng/mL) | 1.8 | 2.5 | 2.1 | 0.497 | 0.615 | 0.190 | 0.462 |

| CA, median 19-9 (IU/mL) | 11.1 | 12.6 | 11.3 | 0.215 | 0.527 | 0.887 | 0.781 |

| Neoadjuvant treatment (%) | 26.7 | 25.5 | 15.3 | 0.795 | < 0.001 | 0.002 | < 0.001 |

| Preoperative complication (%) | 14.2 | 17.3 | 12.9 | 0.678 | 0.910 | 0.637 | 0.883 |

| Treatment | 3.3 | 7.8 | 5.8 | 0.378 | 0.327 | 0.706 | 0.517 |

The rate of emergency surgery tended to be higher in the younger age group, but the difference was not statistically significant (5.0% vs 2.4% vs 1.8%, P = 0.077; Table 2). Patients in their 50s had fewer open surgeries and more minimally invasive surgery than those in their 30s or 40s (P = 0.043). Operative procedures, placement of permanent colostomy, operation time, and estimated blood loss were similar in the three groups, but the combined operation rate was greater among patients in their 30s and 40s than those in their 50s (15.0% vs 15.7% vs 10.7%, P = 0.021). Postoperative pathology outcomes did not differ between the three groups in terms of T stage, N stage, number of positive lymph nodes (LNs), tumor size, proximal resection margin, distal resection margin, and circumferential resection margin, but the number of LNs retrieved from patients in their 30s was greater than from patients in their 40s or 50s (34 vs 29 vs 27, P < 0.001) (Table 3). Patients in their 40s, unlike other groups, had many metastatic lesions (17.5% vs 21.1% vs 14.9%, P = 0.012), and the TNM stage was high (P = 0.002). Tumor differentiation and venous/lymphatic invasion were not different among the three groups, and there were no significant differences in immunohistochemistry (IHC) or molecular pathology test results. In the younger age group, mucinous type cancers, perineural invasion, and BRAF positivity were more frequent, but these findings were not statistically significant (7.5% vs 5.1% vs 4.7%, P = 0.347; 13.3% vs 9.5% vs 7.9%, P = 0.094; 15.8% vs 4.8% vs 3.9%, P = 0.076). Similarly, a greater proportion of microsatellite instability (MSI)-high (H) was found in the younger age group (16.7% vs 9.0% vs 3.7%, P = 0.046). while K-ras mutation was detected less frequently in patients in their 40s (48.5% vs 33.3% vs 44.5%, P = 0.076).

| 30s (n = 120) | 40s (n = 451) | 50s (n = 1044) | P value1 | P value2 | P value3 | P value4 | |

| Emergency (%) | 5.0 | 2.4 | 1.8 | 0.143 | 0.434 | 0.023 | 0.077 |

| Operation type (%) | 0.931 | 0.023 | 0.155 | 0.043 | |||

| Laparoscopy | 55.8 | 59.2 | 70.1 | ||||

| Robot | 35.8 | 31.2 | 21.6 | ||||

| Open | 5.8 | 6.2 | 4.0 | ||||

| Conversion | 1.7 | 1.5 | 2.0 | ||||

| Transanal | 0.8 | 1.8 | 2.2 | ||||

| Operation procedure (%) | 0.847 | 0.914 | 0.897 | 0.983 | |||

| Lesional (CME, TME) | 93.3 | 95.6 | 96.1 | ||||

| Total (TAC, TPC) | 5.0 | 1.8 | 1.1 | ||||

| Multiple | 0 | 0.7 | 0.3 | ||||

| Limited (Segmental, TAE, TAMIS) | 1.7 | 2.0 | 2.6 | ||||

| Combined operation (%) | 15 | 15.7 | 10.7 | 0.835 | 0.008 | 0.172 | 0.021 |

| Permanent colostomy (%) | 3.3 | 4.9 | 3.1 | 0.472 | 0.085 | 0.872 | 0.222 |

| Operative time, median (min) | 200 | 205 | 190 | 0.476 | 0.026 | 0.571 | 0.078 |

| EBL, mean (mL) | 69.4 | 92.9 | 100.0 | 0.331 | 0.685 | 0.316 | 0.555 |

| 30s (n = 120) | 40s (n = 451) | 50s (n = 1044) | P value1 | P value2 | P value3 | P value4 | |

| pT (%) | 0.251 | 0.986 | 0.214 | 0.446 | |||

| Tis | 6.7 | 5.8) | 8.1 | ||||

| T0 | 5.0 | 4.0 | 4.0 | ||||

| T1 | 9.2 | 6.4 | 10.8 | ||||

| T2 | 12.5 | 12.0 | 13.6 | ||||

| T3 | 55.0 | 62.5 | 54.8 | ||||

| T4 | 11.7 | 9.3 | 8.3 | ||||

| Unknown | 0 | 0 | 0.3 | ||||

| pN (%) | 0.419 | 0.289 | 0.831 | 0.521 | |||

| N0 | 56.7 | 50.8 | 57.2 | ||||

| N1 | 24.2 | 28.2 | 25.3 | ||||

| N2 | 16.7 | 17.7 | 14.1 | ||||

| Unknown | 2.5 | 3.3 | 3.4 | ||||

| Positive LN, mean (n) | 1.9 | 1.8 | 1.8 | 0.709 | 0.960 | 0.803 | 0.958 |

| Retrieved LN, mean (n) | 34 | 29 | 27 | 0.030 | 0.015 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 |

| M (%) | 0.438 | 0.003 | 0.386 | 0.012 | |||

| M0 | 81.7 | 78.3 | 84.8 | ||||

| M1 | 17.5 | 21.1 | 14.9 | ||||

| Unknown | 0.8 | 0.7 | 0.3 | ||||

| Stage (%) | 0.138 | < 0.001 | 0.613 | 0.002 | |||

| 0 | 11.7 | 8.6 | 11.3 | ||||

| 1 | 15.8 | 13.1 | 18.6 | ||||

| 2 | 28.3 | 27.1 | 25.7 | ||||

| 3 | 26.7 | 29.3 | 28.3 | ||||

| 4 | 17.5 | 21.1 | 14.8 | ||||

| Unknown | 0 | 0.9 | 1.3 | ||||

| Tumor size, mean (cm) | 4.9 | 4.7 | 4.3 | 0.797 | 0.079 | 0.207 | 0.125 |

| PRM, mean (cm) | 19.2 | 16.6 | 16.3 | 0.044 | 0.699 | 0.395 | 0.530 |

| DRM, mean (cm) | 6.7 | 6.0 | 6.8 | 0.431 | 0.205 | 0.690 | 0.412 |

| CRM, mean (cm) | 0.6 | 0.7 | 0.7 | 0.856 | 0.834 | 0.681 | 0.927 |

| Differentiation (%) | 0.279 | 0.670 | 0.155 | 0.347 | |||

| Well | 22.5 | 17.5 | 18.6 | ||||

| Moderate | 56.7 | 68.3 | 67.0 | ||||

| Poor | 5.0 | 2.9 | 2.4 | ||||

| Mucinous | 7.5 | 5.1 | 4.7 | ||||

| Signet ring cell | 0.8 | 0 | 0.3 | ||||

| Etc. | 0.8 | 0 | 0.1 | ||||

| Unknown | 6.7 | 6.2 | 6.9 | ||||

| Venous invasion (%) | 8.3 | 5.1 | 4.9 | 0.159 | 0.893 | 0.101 | 0.254 |

| Lymphatic invasion (%) | 20.0 | 15.3 | 16.8 | 0.194 | 0.432 | 0.365 | 0.415 |

| Perineural invasion (%) | 13.3 | 9.5 | 7.9 | 0.199 | 0.297 | 0.036 | 0.094 |

| IHC (% positive) | |||||||

| EGFR | 53/63 (84.1) | 210/274 (76.6) | 506/673 (75.2) | 0.197 | 0.636 | 0.113 | 0.275 |

| CDX-2 | 23/24 (95.8) | 84/87 (96.6) | 236/239 (98.7) | 0.869 | 0.194 | 0.268 | 0.338 |

| P53 | 50/52 (96.2) | 217/223 (97.3) | 549/572 (96.0) | 0.657 | 0.369 | 0.951 | 0.668 |

| MLH-1 | 31/33 (93.9) | 162/165 (98.2) | 398/407 (97.8) | 0.158 | 0.767 | 0.174 | 0.326 |

| MSH-2 | 33/33 (100) | 165/165 (100) | 403/408 (98.8) | - | 0.154 | 0.524 | 0.295 |

| MSH-6 | 24/24 (100) | 118/120 (98.3) | 292/295 (98.9) | 0.528 | 0.583 | 0.621 | 0.738 |

| PMS-2 | 19/20 (95) | 97/100 (97) | 240/249 (96.4) | 0.652 | 0.777 | 0.754 | 0.899 |

| BRAF | 3/19 (15.8) | 3/63 (4.8) | 7/180 (3.9) | 0.108 | 0.765 | 0.024 | 0.076 |

| Molecular test (% wild-type) | |||||||

| K-ras | 17/33 (51.5) | 92/138 (66.7) | 152/274 (55.5) | 0.105 | 0.029 | 0.667 | 0.064 |

| N-ras | 20/21 (95.2) | 90/95 (94.7) | 193/200 (96.5) | 0.926 | 0.475 | 0.770 | 0.768 |

| Braf | 12/12 (100) | 51/53 (96.2) | 93/97 (95.9) | 0.502 | 0.917 | 0.478 | 0.778 |

| MSI | |||||||

| MSS | 14/18 (77.8) | 59/67 (88.1) | 142/163 (87.1) | 0.271 | 0.846 | 0.278 | 0.506 |

| MSI-L | 1/18 (5.6) | 2/67 (3.0) | 15/163 (9.2) | 0.605 | 0.102 | 0.607 | 0.248 |

| MSI-H | 3/18 (16.7) | 6/67 (9.0) | 6/163 (3.7) | 0.351 | 0.103 | 0.016 | 0.046 |

The postoperative course was generally similar among the three groups, and there were no differences in postoperative complications or length of stay. However, the enforcement rate of postoperative chemotherapy was significantly greater in the patients in their 40s (58.3% vs 63.9% vs 56.3%, P = 0.032) (Table 4). When comparing survival after excluding stage 4 patients, 5-year overall survival was 92.2% among patients in their 30s, 89.8% among patients in their 40s, and 92.2% among patients in their 50s, and there were no differences between the three groups (P = 0.804) (Figure 2). There were also no differences in 5-year disease-free survival between the three groups (total, 98.6% vs 95.7% vs 96.1%, P = 0.754; local, 98.6% vs 94.3% vs 94.9%, P = 0.579; systemic, 86.4% vs 87.9% vs 86.4%, P = 0.908).

| 30s (n = 120) | 40s (n = 451) | 50s (n = 1044) | P value1 | P value2 | P value3 | P value4 | |

| Gas, median (d) | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0.217 | 0.261 | 0.408 | 0.322 |

| Stool, median (d) | 2 | 2 | 3 | 0.995 | 0.002 | 0.071 | 0.004 |

| Feed, median (d) | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0.569 | 0.655 | 0.736 | 0.827 |

| Postoperative hospital stays, median (d) | 8 | 8 | 8 | 0.545 | 0.748 | 0.656 | 0.834 |

| Postoperative complication (%) | 27.5 | 25.9 | 23.1 | 0.731 | 0.235 | 0.281 | 0.339 |

| Leakage | 5.0 | 6.0 | 6.6 | 0.681 | 0.652 | 0.497 | 0.747 |

| Intraabdominal abscess | 3.3 | 2.4 | 1.6 | 0.587 | 0.289 | 0.184 | 0.319 |

| Wound infection | 2.5 | 1.3 | 1.2 | 0.361 | 0.893 | 0.264 | 0.532 |

| Ileus | 11.7 | 10.4 | 8.4 | 0.695 | 0.218 | 0.235 | 0.299 |

| Bleeding | 2.5 | 0.7 | 1.0 | 0.080 | 0.576 | 0.128 | 0.194 |

| Stoma related | 0 | 0.4 | 0.2 | 0.466 | 0.387 | 0.632 | 0.569 |

| Pulmonary | 0.8 | 1.1 | 0.9 | 0.793 | 0.650 | 0.974 | 0.896 |

| Cardiovascular | 0 | 0 | 0.2 | - | 0.353 | 0.632 | 0.579 |

| Nephrology | 0 | 0.4 | 0.2 | 0.466 | 0.387 | 0.632 | 0.569 |

| Voiding | 0.8 | 0.4 | 0.8 | 0.600 | 0.482 | 0.937 | 0.768 |

| Chyle | 3.3 | 3.8 | 4.0 | 0.822 | 0.817 | 0.714 | 0.921 |

| Other | 3.3 | 2.4 | 2.4 | 0.587 | 0.959 | 0.533 | 0.821 |

| Reoperation (%) | 1.7 | 2.4 | 3.6 | 0.615 | 0.232 | 0.262 | 0.297 |

| Postoperative mortality (%) | 0 | 0.4 | 0.3 | 0.466 | 0.632 | 0.557 | 0.722 |

| Adjuvant treatment (%) | 60.8 | 66.3 | 58.1 | 0.370 | 0.002 | 0.389 | 0.007 |

| Chemotherapy | 58.3 | 63.9 | 56.3 | 0.357 | 0.009 | 0.618 | 0.032 |

| Radiotherapy | 2.5 | 2.4 | 1.8 | 0.946 | 0.429 | 0.580 | 0.679 |

| Recurrence (%) | 15.8 | 20.2 | 16.4 | 0.187 | 0.088 | 0.657 | 0.168 |

| Local | 0.8 | 2.2 | 2.4 | 0.328 | 0.835 | 0.273 | 0.548 |

| Systemic | 6.7 | 6.9 | 6.8 | 0.870 | 0.837 | 0.956 | 0.975 |

| Progression | 8.3 | 11.8 | 7.8 | 0.318 | 0.019 | 0.824 | 0.061 |

| Death (%) | 11.7 | 12.4 | 8.7 | 0.824 | 0.027 | 0.286 | 0.074 |

| Follow-up duration, median(mo) | 26.7 | 25.6 | 24.8 | 0.694 | 0.819 | 0.579 | 0.850 |

In our study, there were relatively fewer K-ras mutations in CRC samples obtained from patients in their 40s than in those of the other age groups. Patients in their 40s had aggressive CRC at a high stage and were administered active perioperative treatment. As a result, the oncologic outcome of patients in their 40s excluding stage 4 patients was not worse than that of those in their 30s and 50s.

CRC in patients in their 40s may represent either late onset hereditary cancer or early onset sporadic cancer. While genetic factors are the major cause of CRC in patients under the age of 40, patients in their 40s have had relatively long periods of exposure to environmental factors, so the importance of environmental factors is relatively high. Therefore, the 40s are considered to be the age at which sporadic cancer, which occurs mainly in people over 50, begins. The distinction between hereditary and sporadic CRC has clinical significance in determining the scope of surgery, surveillance, and prevention of cancer occurrence in the family in advance[15]. Representative hereditary CRCs include familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP) and hereditary nonpolyposis CRC (HNPCC), which are characterized by onset at a young age, frequent synchronous and metachronous colorectal malignancies, and multiple extracolonic malignancies. The most important diagnostic criterion for hereditary CRC is the age of the patient; however, the appropriate cutoff age is unclear, given HNPCC (also called Lynch syndrome) typically occurs later than FAP, and it can therefore be difficult to identify sporadic CRC that developed early based only upon the patient’s age. The Amsterdam criteria or Bethesda guidelines recommend that HNPCC be suspected if the patient is 50 years old or younger and has some other manifestations. However, in a country such as Korea with a large proportion of CRC patients of relatively young age, especially those in their 40s, it may be not available to conduct genetic studies in all patients in their 40s with CRC. On the other hand, if hereditary CRC is not identified where present in these patients, they may miss the additional therapeutic benefits from genetic counseling.

It should be noted that, in recent years, the age of onset of CRC is not only gradually decreasing in Korea, but also worldwide. In statistical analyses based on SEER data, Siegel et al[2] reported that colon cancer incidence rates increased by 1.0% to 2.4% annually since the mid-1980s in patients aged 20 to 39 years and by 0.5% to 1.3% since the mid-1990s in patients aged 40 to 54 years. Similar trends have also been identified in other countries such as Canada and Australia, and because of this, in 2018 the American Cancer Society recommended that the screening age for CRC be lowered from 50 to 45 years[16]. Thus, the dilemma regarding how to appropriately manage CRC patients in their 40s identified in Korea may be occurring in other countries. In this regard, it is clinically important to confirm the characteristics of CRC patients in their 40s compared to those in their 30s and 50s.

In our study, patients in their 40s with CRC had independent characteristics that were distinct from those in their 30s and 50s. The proportion of women was relatively high, co-morbidity was low, and combined operations were frequent. The characteristics of patients in their 40s with CRC tended to be similar to those of patients in their 30s. However, multiple lesions were not as frequent as in those in their 30s, which led to a lower rate of total colectomy, and a significantly lower number of retrieved LNs than in patients in their 30s, similar to the characteristics of patients in their 50s. Contrary to expectation, histological characteristics were not different by age group. In younger patients, there were more cancers of the mucinous type, and greater perineural invasion, BRAF positivity on IHC, and rate of MSI-H, but these findings were not statistically significant.

It is noteworthy that in patients in their 40s, metastases were significantly more frequent at the time of diagnosis, as was pre-/post-surgery chemotherapy. Because many countries, including Korea, begin screening for CRC among average-risk people in their 50s, early-stage CRC in their 50s might be expected to be found relatively frequently by screening. Considering that the age is excluded from screening for CRC, it can be understood that the stage of CRC patients in their 40s is higher than those in their 50s. However, it is very surprising that the stage in the 40s is higher than even in the 30s. One hypothesis is that some of the patients with CRC in their 30s have been diagnosed with FAP or HNPCC by themselves or by their family members, and early CRC may have been detected in surveillance colonoscopy or prophylactically resected specimens. In our study, the frequency of K-ras mutation was significantly lower among patients in their 40s, but more research and consideration will be needed to determine the effect of mutation frequency on staging. Meanwhile, when assessing survival among Stage 1-3 patients, there were no differences between patients in their 40s and those in their 30s or 50s. We could find that the age of 40s itself is not a risk factor for poor survivals although other studies have been controversial about the results[12-14]. As a result, early detection of CRC patients in their 40s will be an important task. Given 54% of CRCs in patients in their 40s are rectal cancer and 28.7% are left-sided colon cancer, a new screening program in which sigmoidoscopy is recommended beginning in the 40s may be considered[17].

Another interesting finding from our study is that the proportion of CRC patients in their 40s did not change significantly throughout the study period, and has remained approximately 10% since 2007. This finding appears to conflict with those from Western countries, where the proportion of patients with CRC in their 40s has increased gradually over the last few decades[2-4]. In addition, the results of a recent analysis using the national registry of Asian countries are contrary to the reported trend in which the age at diagnosis of CRC is decreasing in several Asian countries, including Korea[5-7]. This inconsistency may have arisen because our study was conducted over a relatively short period of analysis. And, in our study, the percentage of CRC patients in their 40s was somewhat greater than in the annual report of cancer statistics in Korea, probably because our study included only patients who underwent surgery[1]. Given a significant proportion (about 10%) of all Korean CRC patients are in their 40s, an age group of major socioeconomic influence, there is an ongoing debate regarding reducing the age at which initiation of screening is recommended[16,18,19].

Our study had some limitations. First, the primary comparators were clinical variables, and immunohistochemistry tests such as epidermal growth factor receptor or CDX-2 were limited, and genetic tests such as ras gene or MSI were performed only in about 10%-50% of patients. In particular, in CRC cases in patients in their 30s, the likelihood of hereditary cancer is high, so it is typically necessary to perform genetic testing for somatic mutations, but there were few results. And, information on whether to diagnose FAP and HNPCC is also insufficient. The second limitation was that even in among patients in their 40s, the patient characteristics may differ between patients in their early and late 40s. Third, there were large differences in patient numbers by age group, with 8-fold or more patients in their 50s than in their 30s. Despite these limitations, our findings can be meaningful in that identification of the characteristics of the growing proportion of CRC patients in their 40s may help to formulate patient management strategies.

In conclusion, patients with CRC in their 40s comprised about 10% of all CRC patients, and most of the tumor characteristics were similar to those in their 30s and 50s in our study. However, their cancers were often found at an aggressive stage compared to those found in the other age groups. Nonetheless, the oncologic outcome was not worse by stage, so it is necessary to actively perform screening tests for early detection. In addition, even in patients in their 40s, the potential for late-onset hereditary CRC must always be considered, but future studies are needed to establish new standards for conducting genetic tests for patients with CRC in their 40s.

Globally, the proportion of young patients with colorectal cancer (CRC), especially in their 40s, is increasing, and this rate of increase is very rapid.

Patients with CRC in their 40s have the potential for both late-onset hereditary CRC and early-onset sporadic CRC. However, few studies have analyzed the characteristics of patients with CRC in their 40s.

The main aim of this study was to determine the proportion of patients with CRC in their 40s and to identify their clinical characteristics, especially compared with those in their 30s and 50s.

We compared patient and tumor characteristics as well as perioperative outcomes of patients in their 30s, 40s, and 50s who received primary resection for CRC. In addition, the 5-year survivals were compared between the three groups, excluding stage 4.

In patients with CRC in their 40s, there were significantly more metastatic lesions and a higher TNM stage. K-ras mutations tended to be low in patients in their 40s, and postoperative chemotherapy was frequently performed in them. Excluding stage 4, the 5-year overall and disease-free survivals of CRC patients in their 40s did not differ from those in their 30s and 50s.

Patients with CRC in their 40s exhibited relatively more metastatic lesions and a more advanced stage, but the oncologic outcomes of patients excluding stage 4 were not inferior compared to those in their 30s and 50s. Therefore, it is necessary to actively perform screening tests for early detection of CRC in those in their 40s.

More analyses of immunohistochemistry or genetic testing results are needed to complement our results. In addition, future studies are also needed to establish new standards for conducting genetic tests for patients with CRC in their 40s.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Oncology

Country/Territory of origin: South Korea

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Sahin Y S-Editor: Wang JL L-Editor: A P-Editor: Ma YJ

| 1. | Jung KW, Won YJ, Hong S, Kong HJ, Lee ES. Prediction of Cancer Incidence and Mortality in Korea, 2020. Cancer Res Treat. 2020;52:351-358. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 78] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 104] [Article Influence: 26.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Siegel RL, Fedewa SA, Anderson WF, Miller KD, Ma J, Rosenberg PS, Jemal A. Colorectal Cancer Incidence Patterns in the United States, 1974-2013. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2017;109. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 568] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 720] [Article Influence: 102.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Virostko J, Capasso A, Yankeelov TE, Goodgame B. Recent trends in the age at diagnosis of colorectal cancer in the US National Cancer Data Base, 2004-2015. Cancer. 2019;125:3828-3835. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 53] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 59] [Article Influence: 11.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Siegel RL, Torre LA, Soerjomataram I, Hayes RB, Bray F, Weber TK, Jemal A. Global patterns and trends in colorectal cancer incidence in young adults. Gut. 2019;68:2179-2185. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 417] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 376] [Article Influence: 75.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Chung RY, Tsoi KKF, Kyaw MH, Lui AR, Lai FTT, Sung JJ. A population-based age-period-cohort study of colorectal cancer incidence comparing Asia against the West. Cancer Epidemiol. 2019;59:29-36. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 26] [Article Influence: 5.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Sung JJY, Chiu HM, Jung KW, Jun JK, Sekiguchi M, Matsuda T, Kyaw MH. Increasing Trend in Young-Onset Colorectal Cancer in Asia: More Cancers in Men and More Rectal Cancers. Am J Gastroenterol. 2019;114:322-329. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 64] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 85] [Article Influence: 17.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Nam S, Choi YJ, Kim DW, Park EC, Kang JG. Risk Factors for Colorectal Cancer in Korea: A Population-Based Retrospective Cohort Study. Ann Coloproctol. 2019;35:347-356. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 8] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Gabriel E, Ostapoff K, Attwood K, Al-Sukhni E, Boland P, Nurkin S. Disparities in the Age-Related Rates of Colorectal Cancer in the United States. Am Surg. 2017;83:640-647. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 9. | Gabriel E, Attwood K, Al-Sukhni E, Erwin D, Boland P, Nurkin S. Age-related rates of colorectal cancer and the factors associated with overall survival. J Gastrointest Oncol. 2018;9:96-110. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 28] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Jeon J, Du M, Schoen RE, Hoffmeister M, Newcomb PA, Berndt SI, Caan B, Campbell PT, Chan AT, Chang-Claude J, Giles GG, Gong J, Harrison TA, Huyghe JR, Jacobs EJ, Li L, Lin Y, Le Marchand L, Potter JD, Qu C, Bien SA, Zubair N, Macinnis RJ, Buchanan DD, Hopper JL, Cao Y, Nishihara R, Rennert G, Slattery ML, Thomas DC, Woods MO, Prentice RL, Gruber SB, Zheng Y, Brenner H, Hayes RB, White E, Peters U, Hsu L; Colorectal Transdisciplinary Study and Genetics and Epidemiology of Colorectal Cancer Consortium. Determining Risk of Colorectal Cancer and Starting Age of Screening Based on Lifestyle, Environmental, and Genetic Factors. Gastroenterology. 2018;154:2152-2164.e19. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 171] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 193] [Article Influence: 32.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Campos FG. Colorectal cancer in young adults: A difficult challenge. World J Gastroenterol. 2017;23:5041-5044. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in CrossRef: 69] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 66] [Article Influence: 9.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Cheong C, Oh SY, Kim YB, Suh KW. Differences in biological behaviors between young and elderly patients with colorectal cancer. PLoS One. 2019;14:e0218604. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 6] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Anele CC, Askari A, Navaratne L, Patel K, Jenkin JT, Faiz OD, Latchford A. The association of age with the clinicopathological characteristics and prognosis of colorectal cancer: a UK single-centre retrospective study. Colorectal Dis. 2020;22:289-297. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 4] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Saraste D, Järås J, Martling A. Population-based analysis of outcomes with early-age colorectal cancer. Br J Surg. 2020;107:301-309. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 35] [Article Influence: 8.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Wells K, Wise PE. Hereditary Colorectal Cancer Syndromes. Surg Clin North Am. 2017;97:605-625. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 26] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Fedewa SA, Siegel RL, Goding Sauer A, Bandi P, Jemal A. Colorectal cancer screening patterns after the American Cancer Society's recommendation to initiate screening at age 45 years. Cancer. 2020;126:1351-1353. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 17] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Yang L, Xiong Z, He W, Xie K, Liu S, Kong P, Jiang C, Guo G, Xia L. Proximal shift of colorectal cancer with increasing age in different ethnicities. Cancer Manag Res. 2018;10:2663-2673. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 12] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Choi YJ, Lee DH, Han KD, Kim HS, Yoon H, Shin CM, Park YS, Kim N. Optimal Starting Age for Colorectal Cancer Screening in an Era of Increased Metabolic Unhealthiness: A Nationwide Korean Cross-Sectional Study. Gut Liver. 2018;12:655-663. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 3] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Abualkhair WH, Zhou M, Ahnen D, Yu Q, Wu XC, Karlitz JJ. Trends in Incidence of Early-Onset Colorectal Cancer in the United States Among Those Approaching Screening Age. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3:e1920407. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 78] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 84] [Article Influence: 21.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |