Published online Dec 21, 2017. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v23.i47.8395

Peer-review started: July 28, 2017

First decision: August 30, 2017

Revised: September 19, 2017

Accepted: September 26, 2017

Article in press: September 26, 2017

Published online: December 21, 2017

To compare the one-week clinical effects of single doses of dexlansoprazole and esomeprazole on grades A and B erosive esophagitis.

We enrolled 175 adult patients with gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD). The patients were randomized in a 1:1 ratio into two sequence groups to define the order in which they received single doses of dexlansoprazole (n = 88) and esomeprazole (n = 87) for an intention-to-treat analysis. The primary end-points were the complete symptom resolution (CSR) rates at days 1, 3, and 7 after drug administration.

Thirteen patients were lost to follow-up, resulting in 81 patients in each group for the per-protocol analysis. The CSRs for both groups were similar at days 1, 3 and 7. In the subgroup analysis, the female patients achieved higher CSRs in the dexlansoprazole group than in the esomeprazole group at day 3 (38.3% vs 18.4%, P = 0.046). An increasing trend toward a higher CSR was observed in the dexlansoprazole group at day 7 (55.3% vs 36.8%, P = 0.09). In the esomeprazole group, female sex was a negative predictive factor for CSR on post-administration day 1 [OR = -1.249 ± 0.543; 95%CI: 0.287 (0.099-0.832), P = 0.022] and day 3 [OR = -1.254 ± 0.519; 95%CI: 0.285 (0.103-0.789), P = 0.016]. Patients with spicy food eating habits achieved lower CSRs on day 1 [37.3% vs 21.4%, OR = -0.969 ± 0.438; 95%CI: 0.380 (0.161-0.896), P = 0.027].

The overall CSR for GERD patients was similar at days 1-7 for both the dexlansoprazole and esomeprazole groups, although a higher incidence of CSR was observed on day 3 in female patients who received a single dose of dexlansoprazole.

Core tip: No existing report has investigated the short-term clinical effects of dexlansoprazole 60 mg vs esomeprazole 40 mg. This study compared the one-week clinical effects of a single dose of the two drugs for grades A and B erosive esophagitis. We enrolled 175 adult patients with gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) and randomized them in a 1:1 ratio into a dexlansoprazole (n = 88) or esomeprazole group (n = 87) for an intention-to-treat analysis (ITT). The primary end-points were the complete symptom resolution (CSR) rates at days 1, 3, and 7. The CSRs for both groups were similar at days 1, 3 and 7. In the subgroup analysis, female patients achieved higher CSRs in the dexlansoprazole group than in the esomeprazole group at day 3 (38.3% vs 18.4%, P = 0.046). In the esomeprazole group, female sex was a negative predictive factor for CSR at post-dose day 1 [OR = -1.249 ± 0.543; 95%CI: 0.287 (0.099-0.832), P = 0.022] and day 3 [OR = -1.254 ± 0.519; 95%CI: 0.285 (0.103-0.789), P = 0.016]. This pilot study suggested that the overall CSR rates for GERD patients were similar at days 1 through 7 for both the dexlansoprazole and esomeprazole groups, although a higher CSR was observed at day 3 in female patients who received a single dose of dexlansoprazole.

- Citation: Liang CM, Kuo MT, Hsu PI, Kuo CH, Tai WC, Yang SC, Wu KL, Wang HM, Yao CC, Tsai CE, Wang YK, Wang JW, Huang CF, Wu DC, Chuah SK, Taiwan Acid-Related Disease Study Group. First-week clinical responses to dexlansoprazole 60 mg and esomeprazole 40 mg for the treatment of grades A and B gastroesophageal reflux disease. World J Gastroenterol 2017; 23(47): 8395-8404

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v23/i47/8395.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v23.i47.8395

Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) is a common gastrointestinal disorder worldwide. GERD continues to increase in incidence with the aging population and the obesity epidemic[1,2]. Based on the Montreal definition, GERD is diagnosed when the reflux of stomach contents causes troublesome symptoms[3], such as heartburn and regurgitation, as well as other atypical or extraesophageal symptoms, such as chest pain, asthma, voice hoarseness, and sleep disturbance[4]. Proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) are widely recognized as superior to other antisecretory therapies, including histamine-2 receptor antagonists (H2RA), and thus play a critical role in pharmacological therapy for the treatment of GERD[5]. Although PPIs represent the mainstay of treatment for healing erosive esophagitis, symptom relief, and preventing complications, several studies have shown that up to 40% of GERD patients report either a partial or a complete lack of response of their symptoms after taking a standard once-daily PPI dose[6-8].

A study comparing the pharmacokinetic effects of different PPIs 12-24 h post-dose showed that the mean percentage of time with a pH > 4 and the average of the pH mean were greater for dexlansoprazole than for esomeprazole (60% vs 42%, P < 0.001 and pH 4.5 vs 3.5, P < 0.001). However, this study did not report the clinical effects after the use of tablets[9]. Rapid onset PPIs for fast symptom relief is an unmet need in GERD treatment. To date, no reports have investigated the differences in short-term clinical effects and timing to symptom relief of GERD between dexlansoprazole 60 mg and esomeprazole 40 mg. Therefore, we conducted a randomized, controlled, open-label study to compare the 7-d clinical effects of single doses of dexlansoprazole (60 mg) and esomeprazole (40 mg) in patients with Los Angeles (LA) grades A and B erosive esophagitis.

This study was funded by the Research Foundation of the Chang Gung Memorial Hospital, Taiwan (CMRPG8D1441). This open-labeled trial was conducted at Kaohsiung Chang Gung Memorial Hospital, Kaohsiung Medical University Hospital, and Kaohsiung Veterans General Hospital in Taiwan. The study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committees of the above three hospitals. All patients provided written informed consent prior to participation. This clinical trial has been registered in a publicly accessible registry (ClinicalTrials.gov number: NCT03128736).

We invited 243 eligible outpatients to join our study. The outpatients were at least 18 years old, presented with clinical symptoms of acid regurgitation, heartburn, and a feeling of acidity in the stomach[10], and had endoscopy-confirmed LA grade A or B erosive esophagitis[11,12]. We enrolled a total of 175 patients using strict inclusion criteria. The exclusion criteria included (1) those who had been taking antisecretory agents, such as PPIs and H2RA, within 2 wk prior to the endoscopy; (2) those who had coexistence of a peptic ulcer or gastrointestinal malignancies, and were pregnant; (3) those who had coexistence of a serious concomitant illness (e.g., decompensated liver cirrhosis and uremia); (4) those who underwent previous gastric surgery; (5) those who were allergic to dexlansoprazole or esomeprazole; and (6) those who had a symptom score less than 12 on a validated questionnaire (Chinese GERDQ)[10].

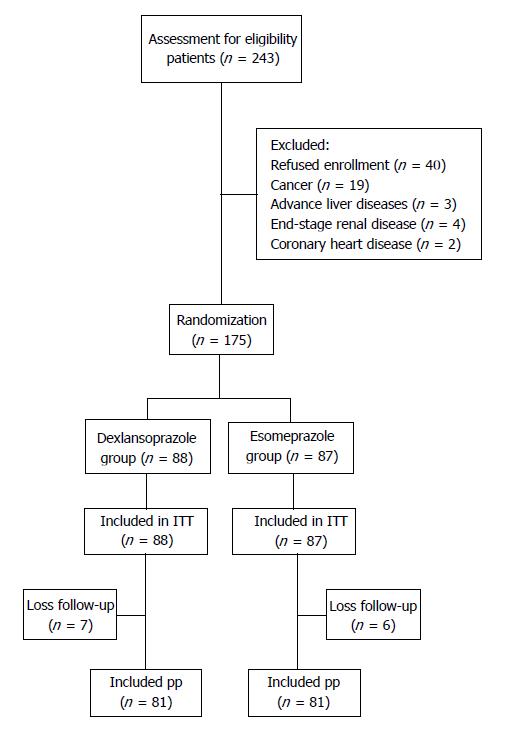

Figure 1 shows the schematic flowchart of the study design. Eligible patients were randomly assigned to receive either dexlansoprazole 60 mg q.d. or esomeprazole 40 mg q.d. for 8 wk as an initial treatment. Randomization was conducted using a computer-generated list of random numbers in a 1:1 ratio into two sequence groups that defined the order in which the patients received a single dose of dexlansoprazole or esomeprazole for an intention-to-treat analysis. An independent staff member assigned the treatments according to consecutive numbers kept in sealed envelopes. Written informed consent was obtained from each patient.

Each patient completed diary cards during the study period. Complete symptom resolution (CSR) was defined as no reflux symptoms leading to troublesome feelings in the 7 d of initial treatment. The patients were asked to complete the Chinese GERDQ upon recruitment[10]. The selected symptoms that best accounted for the differences between the patients with GERD and the controls included acid regurgitation, heartburn, and a feeling of acidity in the stomach. The severity and frequency of symptoms in the questionnaire were graded on a five-point Likert scale as follows: (1) (none: no symptoms/none in the last month); (2) (mild: symptoms could be easily ignored/less than once per month); (3) (moderate: awareness of symptoms but easily tolerated/≥ once per month); (4) (severe: symptoms sufficient to interfere with normal activities/≥ once per week); and (5) (incapacitating: incapacitating symptoms with an inability to perform daily activities or requiring a day off work/≥ once daily)[10]. Blood samples were collected to measure the fasting blood sugar, serum cholesterol, and triglyceride levels. In addition, the body mass index (BMI) was calculated. Upon initial endoscopy, specimens taken from the greater curvature within 5 cm from the pylorus and from the greater curvature of the middle body were subjected to a microscopic examination for Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) using a hematoxylin and eosin stain. No eradication therapy was administered during the study period.

A complete medical history and demographic data were obtained from each patient. The collected variables included age (< 60 or ≥ 60 years), sex, history of smoking, history of alcohol consumption (< 80 g/d or ≥ 80 g/d), coffee ingestion (< 1 cup/d or ≥ 1 cup/d), tea ingestion (< 1 cup/d or ≥ 1 cup/d), coexistence of a systemic disease (yes or no), severity of erosive esophagitis, and BMI. A gastric biopsy for histology and an H. pylori examination were also performed. The patients returned to the clinics for drug refills and evaluation of reflux symptoms after one week. Adverse events were prospectively evaluated. The adverse events were assessed according to a 4-point scale system as follows: none; mild (discomfort, annoying but not interfering with daily work); moderate (discomfort sufficient to interfere with daily work); and severe (discomfort resulting in discontinuation of PPI therapy). Compliance was checked by counting the unused medication at the completion of 7 d of treatment.

CSR was defined as no reflux symptoms sufficient to impair the quality of life before the end of the initial treatment phase. The main outcome measures were the CSR rates at days 1, 3 and 7 of the initial treatment period. All patients who started esomeprazole or dexlansoprazole as their initial treatment were included in the intent-to-treat (ITT) analysis. Patients with poor drug compliance were excluded from the per-protocol (PP) analysis. Poor compliance was defined as taking less than 80% of the total medication during the initial treatment phase.

According to the observations in this study, the CSR rate after a once-daily PPI therapy was approximately 50% at day 7. Assuming that the two types of PPIs provided similar effects on the CSR rates with a standard deviation of less than 10%[13] , we estimated that we required at least 196 patients in each treatment group to demonstrate a 10% absolute difference in the CSR with a type I error of 0.05 and a statistical power of 80% and assuming a 10% loss to follow-up. As a consequence of not achieving the target number, our study was a pilot study.

In this pilot study, the χ2 test with or without Yates correction for continuity and Fisher’s exact test were used when appropriate to compare the rates of CSR, symptom relapse, and esophagitis relapse between the groups. The mean reflux symptom scores between groups were compared using the Wilcoxon rank sum test. All statistical analyses were performed using the SPSS program (version 10.1, Chicago, IL, United States). A P value less than 0.05 was considered significant.

From April 2014 to March 2016, two hundred and forty-three eligible symptomatic patients who had endoscopy-confirmed Los Angeles grade A or B erosive esophagitis were assessed. A total of 175 of these patients were recruited for randomization after excluding 68 patients who refused enrollment (n = 40), cancer patients (n = 19), and patients with advanced liver disease (n = 3), end-stage renal disease (n = 4), and coronary heart disease (n = 2). A total of 88 patients received the dexlansoprazole treatment, and 87 patients received the esomeprazole treatment. A total of 13 patients were lost during the follow-up period (seven in the dexlansoprazole group and 6 in the esomeprazole group) (Figure 1). The baseline characteristics of the two groups were similar in age, sex, diet habits, body mass index, and symptom scores (GERDQ) (Table 1). At days 1, 3, and 7 post-dose, the CSR rates for the dexlansoprazole vs esomeprazole groups were 25.9% vs 28.4% (P = 0.724), 33.3% vs 32.1% (P = 0.867), and 51.9% vs 48.1% (P = 0.637), respectively. The symptoms and frequencies of nighttime reflux were similar in both groups (Table 2). In the subgroup analysis based on sex, females had higher CSR rates in the dexlansoprazole group at day 3 (38.3% vs 18.4%, P = 0.046), and an increasing trend was observed at day 7 (55.3% vs 36.8%, P = 0.09) (Table 3). However, no significant differences were observed in the subgroup analyses based on age and body weight. After splitting the data from the two PPI groups in the multivariate analysis, no dependent factor for CSR was found in the dexlansoprazole group (Table 4). In the esomeprazole group, female sex was a negative predictive factor for CSR at post-dose days 1 [OR = -1.249 ± 0.543; 95%CI: 0.287 (0.099-0.832), P = 0.022] and 3 [OR = -1.254 ± 0.519; 95%CI: 0.285 (0.103-0.789), P = 0.016]. In addition, patients with a habit of consuming spicy foods had lower CSR rates (37.3% vs 21.4%) on day 1 after the multivariate analysis [OR = -0.969 ± 0.438; 95%CI: 0.380 (0.161-0.896), P = 0.027] (Table 5). No dependent factor was found on days 3 and 7.

| Variables | Dexlansoprazole | Esomeprazole | P value |

| Age (mean ± SD, yr) | 50.6 ± 13.3 | 49.9 ± 12.8 | 0.985 |

| Male sex | 34 (42.0) | 43 (53.1) | 0.137 |

| Smoking | 12 (14.8) | 9 (11.1) | 0.483 |

| Alcohol use | 22 (27.2) | 22 (27.2) | 1.000 |

| Ingestion of coffee | 44 (54.3) | 36 (44.4) | 0.209 |

| Ingestion of tea | 58 (71.6) | 49 (60.5) | 0.230 |

| Betel nut | 4 (4.9) | 1 (1.2) | 0.173 |

| Spicy food | 52 (64.2) | 51 (63.0) | 0.870 |

| Sweet food | 72 (88.9) | 75 (92.6) | 0.416 |

| Body mass index | 25.4 ± 4.8 | 24.9 ± 4.4 | 0.420 |

| Waist girth | 88.8 ± 12.2 | 88.7 ± 11.4 | 0.361 |

| Metabolic syndrome | 36 (44.4) | 38 (46.9) | 0.950 |

| Atypical symptoms | |||

| Chest pain | 38 (46.9) | 39 (48.1) | 0.588 |

| Dysphagia | 20 (24.7) | 22 (27.2) | 0.557 |

| Regurgitation of food | 29 (35.8) | 31 (38.3) | 0.561 |

| Nausea | 26 (32.1) | 23 (28.4) | 0.544 |

| Hiccup | 37 (45.7) | 44 (54.3) | 0.300 |

| Foreign body sensation (throat) | 48 (59.3) | 40 (49.4) | 0.301 |

| Foreign body sensation (chest) | 16 (19.8) | 16 (19.8) | 0.604 |

| Hoarseness | 28 (34.6) | 28 (34.6) | 0.604 |

| Throat cleaning | 44 (54.3) | 44 (54.3) | 0.602 |

| Cough | 38 (46.9) | 34 (42.0) | 0.516 |

| Sore throat | 20 (24.7) | 20 (24.7) | 0.604 |

| Dry mouth | 54 (66.7) | 52 (64.2) | 0.590 |

| Bad breath | 29 (35.8) | 30 (37.0) | 0.590 |

| Epigastric pain | 36 (44.4) | 45 (55.6) | 0.197 |

| Epigastric fullness | 65 (80.2) | 54 (66.7) | 0.111 |

| Insomnia | 36 (44.4) | 28 (34.6) | 0.199 |

| Sinusitis | 7 (8.6) | 14 (17.3) | 0.102 |

| Otitis media | 5 (6.2) | 5 (6.2) | 1.000 |

| Sugar | 97.4 ± 12.5 | 97.0 ± 12.8 | 0.604 |

| Cholesterol | 205.3 ± 36.7 | 207.7 ± 35.4 | 0.971 |

| Triglyceride | 121.9 ± 57.2 | 113.7 ± 64.7 | 0.284 |

| HDL | 54.7 ± 18.2 | 55.3 ± 14.4 | 0.866 |

| LDL | 127.0 ± 32.7 | 127.5 ± 32.8 | 0.942 |

| H. pylori infection | |||

| Previous history - no | 10 (12.3) | 15 (18.5) | 0.553 |

| Current infection - no | 10 (12.3) | 12 (14.8) | 0.703 |

| Endoscopic findings | |||

| Hiatal hernia | 10 (12.3) | 15 (18.5) | 0.347 |

| GEFV (grade 3 or 4) | 7 (8.6) | 8 (9.9) | 0.521 |

| Esophagitis grade B | 15 (18.5) | 13 (16.0) | 0.678 |

| Variables | Dexlansoprazole | Esomeprazole | P value |

| CSR Day 1 | 21 (25.9) | 23 (28.4) | 0.724 |

| CSR Day 3 | 27 (33.3) | 26 (32.1) | 0.867 |

| CSR Day 7 | 42 (51.9) | 39 (48.1) | 0.637 |

| Night reflux | 45 (76.3) | 40 (74.1) | 0.787 |

| Night heart burn | 20 (33.9) | 18 (33.3) | 0.949 |

| Night acid reflux | 20 (33.9) | 19 (35.2) | 0.886 |

| Frequency of night symptoms | 2.7 ± 2.0 | 2.7 ± 2.4 | 0.343 |

| Time | Gender | Dexlansoprazole | Esomeprazole | P value |

| CSR Day 1 | Female | 13 (27.7) | 6 (15.8) | 0.192 |

| Male | 8 (23.5) | 17 (39.5) | 0.136 | |

| CSR Day 3 | Female | 18 (38.3) | 7 (18.4) | 0.046 |

| Male | 9 (26.5) | 19 (44.2) | 0.109 | |

| CSR Day 7 | Female | 26 (55.3) | 14 (36.8) | 0.090 |

| Male | 16 (47.1) | 25 (58.1) | 0.333 |

| Time | PPI | Clinical factors | CSR | Coefficient of variation | Odds ratio (95%CI) | P value |

| Day 1 | Dexlansoprazole | Null | ||||

| Esomeprazole | Female | 15.80% | -1.249 ± 0.543 | 0.285 (0.103-0.789) | 0.022 | |

| Day 3 | Dexlansoprazole | Null | ||||

| Esomeprazole | Female | 18.40% | -1.254 ± 0.519 | 0.287 (0.099-0.832) | 0.016 | |

| Day 7 | Dexlansoprazole | Null | ||||

| Esomeprazole | Null |

| Time | Clinical factor | CSR | Coefficient of variation | Odds ratio (95%CI) | P value |

| Day 1 | Spicy food | No: 37.3% | -0.969 ± 0.438 | 0.380 (0.161-0.896) | 0.027 |

| Yes: 21.4% | |||||

| Day 3 | Null | ||||

| Day 7 | Null |

We conducted a randomized, controlled, open-label study to compare the 7-d clinical effects of single doses of dexlansoprazole 60 mg and esomeprazole 40 mg for GERD patients. We observed that the overall CSR rates for GERD patients were similar at days 1 through 7 of treatment for both the dexlansoprazole and esomeprazole groups. However, in our subgroup analysis based on sex, we observed that females had higher CSR rates in the dexlansoprazole group at day 3 (38.3% vs 18.4%, P = 0.046), and an increasing trend was observed at day 7 (55.3% vs 36.8%, P = 0.09). The logistic regression analysis showed that female sex was a negative predictive factor for CSR on post-dose days 1 [OR = -1.249 ± 0.543; 95%CI: 0.287 (0.099-0.832), P = 0.022] and 3 [OR = -1.254 ± 0.519; 95%CI: 0.285 (0.103-0.789), P = 0.016] in the esomeprazole group. We also found that patients with the habit of eating spicy foods had lower CSR rates (37.3% vs 21.4%) on day 1 after the multivariate analysis [OR = -0.969 ± 0.438; 95%CI: 0.380 (0.161-0.896), P = 0.027].

Both dexlansoprazole and esomeprazole are potent PPIs for gastric acid suppression with excellent symptom relief for patients with GERD[14-19]. The advantage of dexlansoprazole MR (Takeda Pharmaceuticals, Osaka, Japan) is that it employs a novel approach by which its dual delayed-release (DDR) formulation prolongs the plasma concentration and ultimately extends the duration of acid suppression[14], thereby offering a twice-daily dosing effect in a one-time dose. Metz et al[15] found that patients who received a 60-mg dose of dexlansoprazole MR satisfactorily controlled heartburn (median of 91%-96% for 24-h heartburn-free days and 96%-99% for heartburn-free nights). Moreover, Sharma et al[16] reported that 92%-95% of patients were healed using dexlansoprazole MR for 8 wk. Conversely, esomeprazole (40 mg) is a delayed-release formulation with single-release characteristics that produces maximum plasma concentrations at approximately 1.6 h post-dose. Approximately 73%-75% heartburn-free days and 85%-91% heartburn-free nights were observed in patients who received 40 mg of esomeprazole for 4 wk[17-19]. In addition, esomeprazole at 40 mg/d also achieved good healing rates (87%-94.1%) for erosive esophagitis after 8 wk of treatment[18-20].

However, no direct head-to-head comparative report has investigated the short-term clinical effects or timing to symptom relief of GERD between dexlansoprazole at 60 mg and esomeprazole at 40 mg. Wu et al[21] reported an indirect comparative study that revealed that the dexlansoprazole 30 mg dose was more effective than esomeprazole at the 20 mg or 40 mg dose (RR = 2.01, 95%CI: 1.15-3.51; RR = 2.17, 95%CI: 1.39-3.38, respectively) for patients with non-erosive esophagitis at 4 wk. However, no significant differences were found in the healing rates of erosive esophagitis. A one-day comparative pH study showed that dexlansoprazole had a higher mean percentage of time with a pH > 4 than esomeprazole (58% and 48%, P = 0.003) at 0-24 h post-dose[9]. Unfortunately, differences in the clinical effects between these two PPIs were not mentioned.

In this study, we found that the symptoms and frequencies of nighttime reflux were similar between the dexlansoprazole and esomeprazole groups (P = 0.787 and P = 0.343, respectively). At days 1, 3, and 7 post-dose, the CSR rates between the two groups were similar (25.9% vs 28.4%, P = 0.724, 33.3% vs 32.1%, P = 0.867, and 51.9% vs 48.1%, P = 0.637, respectively). Nevertheless, we also observed that female patients had higher CSR rates in the dexlansoprazole group (P = 0.046) and an increasing trend for the effect on day 7 (P = 0.09) when we performed the subgroup analysis based on sex. Remarkably, our logistic regression analysis showed that female sex was a negative predictive factor for CSR on post-dose days 1 [OR = -1.249 ± 0.543; 95%CI: 0.287 (0.099-0.832), P = 0.022] and 3 [OR = -1.254 ± 0.519; 95%CI: 0.285 (0.103-0.789), P = 0.016] in the esomeprazole group. These findings implied that esomeprazole at 40 mg required more time (3 d) than dexlansoprazole at 60 mg to attain CSR in females. Several possible mechanisms may underlie these observations. First, both esomeprazole and dexlansoprazole are extensively metabolized in the liver by oxidation, reduction, and subsequent conversion of sulfate, glucuronide and glutathione conjugates to inactive metabolites. Oxidative metabolites are formed by the cytochrome P450 (CYP) enzyme system, mainly by CYP2C19 and CYP3A4[22,23]. In the pharmacokinetics report of esomeprazole[24], the mean exposure (AUC) to esomeprazole increases from 4.32 μmol·h/L on day 1 to 11.2 μmol·h/L on day 5 after a 40-mg once-daily dose, indicating that the pharmacokinetics of esomeprazole are time- and dose-dependent[25]. For dexlansoprazole[26,27], no accumulation of dexlansoprazole occurs after multiple once-daily doses of 60 mg, although the mean AUC and max concentration (Cmax) values of dexlansoprazole are slightly higher (less than 10%) on day 5 than on day 1. We validated this finding by calculating the Cmax of dexlansoprazole, which was 16 μmol·h/L on day 1 and 17.67 μmol·h/L on day 5. As a result, dexlansoprazole almost achieved the target concentration on day 1. Second, ample evidence has shown that estrogen and progestogen can enhance relaxation of the lower esophageal sphincters and induce GERD symptoms[28-30], especially in post-menopausal women taking hormone replacement therapy (HRT)[31-36]. These hypotheses might explain why female patients taking esomeprazole needed at least 3 more days to accumulate a sufficient plasma concentration to achieve plateau levels and desirable clinical effects.

Another observation in this study was the lower CSR rates in patients with the habit of eating spicy foods in the esomeprazole group at day 1 after the multivariate analysis. No reliable data are available in the existing literature regarding the role of diet or specific foods or drinks in GERD[37]. Some foods are believed to induce or worsen GERD symptoms in daily clinical practice, and this belief has led to advising patients to avoid the suspect foods[38]. Nebel et al[39] demonstrated that fried foods, spicy foods, and alcohol were the most common precipitating factors of heartburn, but this study had no control group and did not quantify the intake of dietary items. In contrast, our study used a dietary questionnaire to estimate the frequency of the consumption of different types of food.

In addition to the above shortcoming, this study has other limitations. First, we enrolled only patients with Los Angeles grade A or B erosive esophagitis in this study and not those with Los Angeles grade C or D erosive esophagitis or Barrett’s esophagus. As a result, the study may not represent the clinical effects of the entire GERD population. Second, this study used dietary questionnaires to estimate the frequency of consumption of different types of foods but did not quantify the fat or carbohydrate content. Nonetheless, this pilot study is the first important report to compare the clinical efficacy of a one-week dual delayed-release treatment with dexlansoprazole at 60 mg and esomeprazole at 40 mg for grades A and B GERD patients, since fast symptomatic relief is an important unmet need in the treatment of GERD.

In conclusion, the overall CSR rates for GERD were similar at days 1 through 7 for both the dexlansoprazole and esomeprazole groups, although a higher CSR was observed at day 3 in female patients who received a single dose of dexlansoprazole. Since rapid onset of proton-pump inhibitors for fast symptom relief is an unmet need for the treatment of GERD and no report have investigated the short-term clinical effects of dexlansoprazole 60 mg vs esomeprazole 40 mg, this finding of this pilot study is novel. Furthermore, these findings may have important implications for clinical practice when treating patients with grades A and B GERD. This issue was hampered by the small sample size. Thus, we believe that large-scale comparative studies are necessary.

Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) is a common gastrointestinal disorder worldwide and continues to increase in incidence due to the aging population and obesity epidemic. Although proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) represent the mainstay of treatment for healing erosive esophagitis, symptom relief, and preventing complications, several studies have shown that up to 40% of GERD patients report either a partial or a complete lack of response of their symptoms after taking a standard once daily PPI dose. Rapid onset proton-pump inhibitors for fast symptom relief is an unmet need for GERD treatment. To date, no reports have investigated the short-term clinical effects and timing to symptom relief of gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) between dexlansoprazole (60 mg) and esomeprazole (40 mg). This report is the first randomized, controlled, open-label study to compare the 7-d clinical effects of single doses of dexlansoprazole at 60 mg and esomeprazole at 40 mg for LA grades A and B erosive esophagitis.

A study comparing the pharmacokinetic effects of different PPIs 12-24 h post-dose showed that the mean percentage of time with a pH > 4 and the average of the pH mean were greater for dexlansoprazole than for esomeprazole (60% vs 42%, P < 0.001 and pH 4.5 vs 3.5, P < 0.001). However, this study did not report the clinical effects after the use of tablets. Therefore, the significance of solving these problems for future research in this field should be based on large-scale, head-to-head comparisons of these PPIs on immediate symptom relief for GERD to fulfill the unmet need in real-world treatment.

The main objectives realized in this study motivated us to conduct this randomized, controlled, open-label study that compared the 7-d clinical effects of single doses of dexlansoprazole at 60 mg and esomeprazole at 40 mg for LA grades A and B erosive esophagitis.

This study was funded by the Research Foundation of the Chang Gung Memorial Hospital, Taiwan (CMRPG8D1441), and has been registered in a publicly accessible registry (ClinicalTrials.gov number: NCT03128736). We enrolled 175 adult GERD subjects and randomized them in a 1:1 ratio into two sequence groups that defined the order in which they received single doses of dexlansoprazole (n = 88) and esomeprazole (n = 87) for an ITT. Written informed consent was obtained from each patient. The patients were asked to complete the Chinese GERDQ upon recruitment. Blood samples were collected to measure the fasting blood sugar, serum cholesterol, and triglyceride levels. In addition, the BMI was calculated. A complete medical history and demographic data were obtained from each patient. The primary end points were the complete symptom resolution (CSR) rates at days 1, 3, and 7. CSR was defined as no reflux symptoms sufficient to impair the quality of life before the end of the initial treatment phase. The main outcome measures were the CSR rates at days 1, 3 and 7 of the initial treatment period. All patients starting esomeprazole or dexlansoprazole as their initial treatment were included in the ITT analysis. Patients with poor drug compliance were excluded from the PP analysis.

Thirteen patients were lost during the follow up period, resulting in the inclusion of 81 patients in each group in the PP analysis. The CSRs for both groups were similar at days 1, 3 and 7. In the subgroup analysis, female patients achieved higher CSRs in the dexlansoprazole group than in the esomeprazole group at day 3 (38.3% vs 18.4%, P = 0.046). An increasing trend toward CSR was observed at day 7 (55.3% vs 36.8%, P = 0.09). In the esomeprazole group, female sex was a negative predictive factor for CSR at post-dose days 1 (OR = -1.249 ± 0.543; 95%CI: 0.287 (0.099-0.832), P = 0.022) and 3 (OR = -1.254 ± 0.519; 95%CI: 0.285 (0.103-0.789), P = 0.016). Patients with spicy food eating habits achieved lower CSRs on day 1 (37.3% vs 21.4%, OR = -0.969 ± 0.438; 95%CI: 0.380 (0.161-0.896), P = 0.027).

The conclusion of this study was that the overall CSR rates for GERD were similar on days 1 through 7 for both the dexlansoprazole and esomeprazole groups, although a higher incidence was observed on day 3 in female patients who received a single dose of dexlansoprazole. The findings of this study are novel, since no report has investigated the short-term clinical effects of dexlansoprazole 60 mg vs esomeprazole 40 mg. This comparison represents an unmet need for GERD treatment in real-world clinical practice. The findings in this study could have important implications for clinical practice in the future for the treatment of grade A and B GERD patients. Furthermore, this study observed that female sex was a negative predictive factor for CSR at post-dose days 1 and 3 in the esomeprazole group. These findings implied that esomeprazole at 40 mg required more time (3 d) than dexlansoprazole at 60 mg to attain CSR in females. The new theories proposed suggest that these observations could be due to differences in the pharmacokinetics of esomeprazole and dexlansoprazole. Esomeprazole is time- and dose-dependent, especially at days 1 and 5. No accumulation of dexlansoprazole occurs after multiple once-daily doses at 60 mg. The authors validated this possibility by calculating the Cmax of dexlansoprazole, which was 16 μmol·h/L on day 1 and 17.67 μmol·h/L on day 5. As a result, dexlansoprazole almost achieved the target concentration on day 1. In addition, there is ample evidence that estrogen and progestogen enhance relaxation of the lower esophageal sphincters and induce GERD symptoms, especially in post-menopausal women taking hormone replacement therapy. These hypotheses could explain why female patients taking esomeprazole needed at least 3 more days to accumulate a sufficient plasma concentration to achieve plateau levels and desirable clinical effects.

The important message of this study is that rapid onset PPIs for fast symptom relief remains an unmet need for GERD treatment. However, no report has investigated the short-term clinical effects of dexlansoprazole 60 mg vs esomeprazole 40 mg. Thus, the findings of this pilot study are novel and may have important implications for clinical practice in the future for the treatment of patients with grades A and B GERD. This pilot study was hampered by the small sample size. We believe that large-scale randomized controlled trials are necessary to further fulfill the future perspectives.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: Taiwan

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): A

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P- Reviewer: Cicala M, Skrypnyk IN, Thomopoulos KC S- Editor: Ma YJ L- Editor: Ma JY E- Editor: Huang Y

| 1. | El-Serag HB. Time trends of gastroesophageal reflux disease: a systematic review. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;5:17-26. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 295] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 428] [Article Influence: 25.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | El-Serag HB, Graham DY, Satia JA, Rabeneck L. Obesity is an independent risk factor for GERD symptoms and erosive esophagitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100:1243-1250. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 391] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 373] [Article Influence: 19.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Peery AF, Dellon ES, Lund J, Crockett SD, McGowan CE, Bulsiewicz WJ, Gangarosa LM, Thiny MT, Stizenberg K, Morgan DR. Burden of gastrointestinal disease in the United States: 2012 update. Gastroenterology. 2012;143:1179-1187.e1-3. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 1355] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 1373] [Article Influence: 114.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 4. | Modlin IM, Moss SF. Symptom evaluation in gastroesophageal reflux disease. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2008;42:558-563. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 8] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Kahrilas PJ, Shaheen NJ, Vaezi MF, Hiltz SW, Black E, Modlin IM, Johnson SP, Allen J, Brill JV; American Gastroenterological Association. American Gastroenterological Association Medical Position Statement on the management of gastroesophageal reflux disease. Gastroenterology. 2008;135:1383-1391, 1391.e1-1391.e5. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 438] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 371] [Article Influence: 23.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Hershcovici T, Fass R. An algorithm for diagnosis and treatment of refractory GERD. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2010;24:923-936. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 45] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Fass R. Proton pump inhibitor failure--what are the therapeutic options? Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104 Suppl 2:S33-S38. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 61] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 63] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Revicki DA, Wood M, Maton PN, Sorensen S. The impact of gastroesophageal reflux disease on health-related quality of life. Am J Med. 1998;104:252-258. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 9. | Kukulka M, Eisenberg C, Nudurupati S. Comparator pH study to evaluate the single-dose pharmacodynamics of dual delayed-release dexlansoprazole 60 mg and delayed-release esomeprazole 40 mg. Clin Exp Gastroenterol. 2011;4:213-220. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 26] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Wong WM, Lai KC, Lam KF, Hui WM, Hu WH, Lam CL, Xia HH, Huang JQ, Chan CK, Lam SK. Prevalence, clinical spectrum and health care utilization of gastro-oesophageal reflux disease in a Chinese population: a population-based study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2003;18:595-604. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 11. | Lundell LR, Dent J, Bennett JR, Blum AL, Armstrong D, Galmiche JP, Johnson F, Hongo M, Richter JE, Spechler SJ. Endoscopic assessment of oesophagitis: clinical and functional correlates and further validation of the Los Angeles classification. Gut. 1999;45:172-180. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 12. | Vakil N, van Zanten SV, Kahrilas P, Dent J, Jones R; Global Consensus Group. The Montreal definition and classification of gastroesophageal reflux disease: a global evidence-based consensus. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:1900-1920; quiz 1943. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 2368] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 2220] [Article Influence: 123.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 13. | Jones B, Jarvis P, Lewis JA, Ebbutt AF. Trials to assess equivalence: the importance of rigorous methods. BMJ. 1996;313:36-39. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 14. | Katz PO, Gerson LB, Vela MF. Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of gastroesophageal reflux disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2013;108:308-328; quiz 329. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 1136] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 1015] [Article Influence: 92.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Metz DC, Howden CW, Perez MC, Larsen L, O’Neil J, Atkinson SN. Clinical trial: dexlansoprazole MR, a proton pump inhibitor with dual delayed-release technology, effectively controls symptoms and prevents relapse in patients with healed erosive oesophagitis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2009;29:742-754. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 48] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 47] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Sharma P, Shaheen NJ, Perez MC, Pilmer BL, Lee M, Atkinson SN, Peura D. Clinical trials: healing of erosive oesophagitis with dexlansoprazole MR, a proton pump inhibitor with a novel dual delayed-release formulation--results from two randomized controlled studies. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2009;29:731-741. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 84] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 76] [Article Influence: 5.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Richter JE, Kahrilas PJ, Johanson J, Maton P, Breiter JR, Hwang C, Marino V, Hamelin B, Levine JG; Esomeprazole Study Investigators. Efficacy and safety of esomeprazole compared with omeprazole in GERD patients with erosive esophagitis: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96:656-665. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 63] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Kahrilas PJ, Falk GW, Johnson DA, Schmitt C, Collins DW, Whipple J, D’Amico D, Hamelin B, Joelsson B. Esomeprazole improves healing and symptom resolution as compared with omeprazole in reflux oesophagitis patients: a randomized controlled trial. The Esomeprazole Study Investigators. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2000;14:1249-1258. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 19. | Schmitt C, Lightdale CJ, Hwang C, Hamelin B. A multicenter, randomized, double-blind, 8-week comparative trial of standard doses of esomeprazole (40 mg) and omeprazole (20 mg) for the treatment of erosive esophagitis. Dig Dis Sci. 2006;51:844-850. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 41] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Hsu PI, Lu CL, Wu DC, Kuo CH, Kao SS, Chang CC, Tai WC, Lai KH, Chen WC, Wang HM. Eight weeks of esomeprazole therapy reduces symptom relapse, compared with 4 weeks, in patients with Los Angeles grade A or B erosive esophagitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;13:859-66.e1. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 17] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Wu MS, Tan SC, Xiong T. Indirect comparison of randomised controlled trials: comparative efficacy of dexlansoprazole vs. esomeprazole in the treatment of gastro-oesophageal reflux disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2013;38:190-201. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 19] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Stedman CA, Barclay ML. Review article: comparison of the pharmacokinetics, acid suppression and efficacy of proton pump inhibitors. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2000;14:963-978. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 23. | Shin JM, Kim N. Pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of the proton pump inhibitors. J Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2013;19:25-35. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 210] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 241] [Article Influence: 21.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Junghard O, Hassan-Alin M, Hasselgren G. The effect of the area under the plasma concentration vs time curve and the maximum plasma concentration of esomeprazole on intragastric pH. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2002;58:453-458. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 53] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 56] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Andersson T, Röhss K, Bredberg E, Hassan-Alin M. Pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of esomeprazole, the S-isomer of omeprazole. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2001;15:1563-1569. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 26. | Metz DC, Vakily M, Dixit T, Mulford D. Review article: dual delayed release formulation of dexlansoprazole MR, a novel approach to overcome the limitations of conventional single release proton pump inhibitor therapy. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2009;29:928-937. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 85] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 75] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Behm BW, Peura DA. Dexlansoprazole MR for the management of gastroesophageal reflux disease. Expert Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;5:439-445. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 16] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Smout AJPM. Gastro-oesophageal reflux disease. Pathogenesis and Diagnosis. In Evolving concepts in Gastrointestinal Motility. Edited by Champion MC, Orr WC. Oxford, England: Blackwell Science; 1996; 46-63. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 29. | Van Thiel DH, Gavaler JS, Stremple J. Lower esophageal sphincter pressure in women using sequential oral contraceptives. Gastroenterology. 1976;71:232-234. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 30. | Bruce LA, Behsudi FM. Progesterone effects on three regional gastrointestinal tissues. Life Sci. 1979;25:729-734. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 31. | Menon S, Prew S, Parkes G, Evans S, Smith L, Nightingale P, Trudgill N. Do differences in female sex hormone levels contribute to gastro-oesophageal reflux disease? Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;25:772-777. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 9] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Nordenstedt H, Zheng Z, Cameron AJ, Ye W, Pedersen NL, Lagergren J. Postmenopausal hormone therapy as a risk factor for gastroesophageal reflux symptoms among female twins. Gastroenterology. 2008;134:921-928. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 35] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Zheng Z, Margolis KL, Liu S, Tinker LF, Ye W; Women’s Health Initiative Investigators. Effects of estrogen with and without progestin and obesity on symptomatic gastroesophageal reflux. Gastroenterology. 2008;135:72-81. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 17] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Jacobson BC, Moy B, Colditz GA, Fuchs CS. Postmenopausal hormone use and symptoms of gastroesophageal reflux. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168:1798-1804. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 23] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Alvarez-Sánchez A, Rey E, Achem SR, Díaz-Rubio M. Does progesterone fluctuation across the menstrual cycle predispose to gastroesophageal reflux? Am J Gastroenterol. 1999;94:1468-1471. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 16] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Close H, Mason JM, Wilson D, Hungin AP. Hormone replacement therapy is associated with gastro-oesophageal reflux disease: a retrospective cohort study. BMC Gastroenterol. 2012;12:56. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 15] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Festi D, Scaioli E, Baldi F, Vestito A, Pasqui F, Di Biase AR, Colecchia A. Body weight, lifestyle, dietary habits and gastroesophageal reflux disease. World J Gastroenterol. 2009;15:1690-1701. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in CrossRef: 105] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 108] [Article Influence: 7.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 38. | DeVault KR, Castell DO; American College of Gastroenterology. Updated guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of gastroesophageal reflux disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100:190-200. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 579] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 503] [Article Influence: 26.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Nebel OT, Fornes MF, Castell DO. Symptomatic gastroesophageal reflux: incidence and precipitating factors. Am J Dig Dis. 1976;21:953-956. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |