Published online Jun 7, 2011. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v17.i21.2681

Revised: February 27, 2011

Accepted: March 6, 2011

Published online: June 7, 2011

Casais et al have reported an inverse correlation between serum phosphate and body weight after administration of sodium phosphate at a dose of 60 g. Our group has already described the relationship between body weight and hyperphosphatemia with these preparations, although our study was not quoted by Casais. We performed a pharmacokinetic study involving 13 volunteers who were divided into two groups on the basis of body weight: group I consisting of seven women with a median weight of 60 kg and group IIconsisting of five men and one woman with a median weight of 119.2 kg. Group I developed higher peak phosphate levels and maintained these levels above the subjects in Group II for a prolonged time period despite adequate hydration being ensured with frequent monitoring of weight, fluid intake and total body weight. Our study demonstrated that adequate hydration does not protect against the secondary effects of hyperphosphatemia. In the study by Casais et al, 66% of the study subjects were women, the correlation between serum phosphate and gender in their data also appears to be important. Women are at higher risk of acute phosphate nephropathy due to a diminished volume of distribution of the high dose of ingested phosphate. Decreased volume of distribution in women is due to diminished body weight. This is further compounded by decreased creatinine clearance in females.

- Citation: Deepak P, Ehrenpreis ED. Lower body weight and female gender: Hyperphosphatemia risk factors after sodium phosphate preparations. World J Gastroenterol 2011; 17(21): 2681-2682

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v17/i21/2681.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v17.i21.2681

Casais et al[1] have described an inverse relationship between serum phosphate and body weight after administration of sodium phosphate at a dose of 60 g (90 mL) in 100 consecutive patients. Significantly, adequate hydration was provided to their patients with ingestion of 4 L of clear liquids. Our group has already described the relationship between body weight and hyperphosphatemia after sodium phosphate preparations and determined the pharmacokinetic basis for this observation[2-4], although our studies were not referenced by Casais et al[1]. In our study, we administered a single half dose (45 mL) of Fleet Phospho-Soda containing 30 g of sodium phosphate to 13 normal volunteers consisting of two groups. Group I had seven women with a median weight of 60 kg, and Group II had five men and one woman with a median weight of 119.2 kg. Multiple serum and urine levels of phosphate, calcium, ionized calcium and other electrolytes were measured for 12 h. Hydration was maintained throughout the study by monitoring the weight, fluid intake, and total body water, with increased intake promoted for declines in any value.

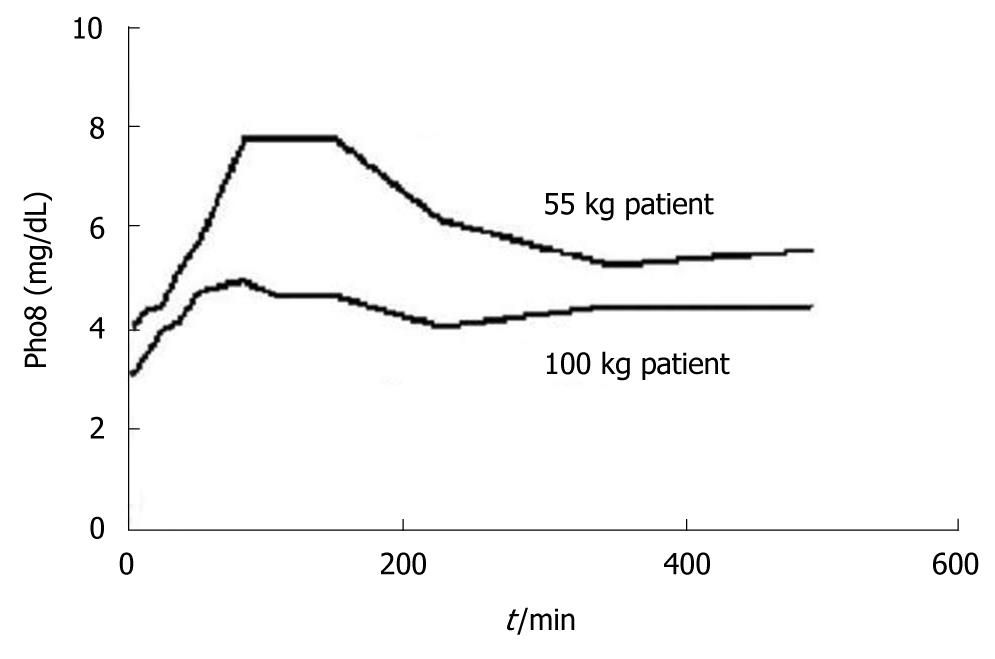

The subjects in Group I developed higher peak phosphate levels and maintained these levels above the subjects in Group II for a prolonged time period (Figure 1). The normalized area under the phosphate vs time curve was much higher in group I (1120 ± 190 mg/dL per min) than in group II (685 ± 136 mg/dL per min), P < 0.001. Urinary excretion of calcium was significantly lower in group I (mean 16.4 ± 7.6 mg) than in group II (mean 39.2 ± 7.8 mg), P < 0.001, and most subjects in Group I had a prolonged time of abnormal ionized calcium levels during the study. Our study demonstrated that individuals, especially women, develop high serum phosphate levels for prolonged periods of time after ingesting sodium phosphate, even under the idealized condition of continuous monitoring of fluids and weight as done in this study. This suggests that adequate hydration does not protect against the secondary effects of hyperphosphatemia, as others have proposed[5,6]. Markowitz et al[7] has published 37 cases of acute phosphate nephropathy (APN), 30 (81%) of them were females. In the study by Casais et al[1] 66% of the study group were women, the correlation between serum phosphate and gender in their data also appears to be important. Pharmacokinetics demonstrates that women of diminished body weight become extremely hyperphosphatemic based on their diminished volume of distribution for the high dose of ingested phosphate. This is further compounded by decreased creatinine clearance in this group (a function dependent in part on body weight). Despite adequate fluid intake, these subjects are at very high risk for renal damage and acute phosphate nephropathy. Females, especially those of lower body weight should avoid using sodium phosphate laxatives for colonoscopic preparation.

Peer reviewers: Rafiq A Sheikh, MBBS, MD, MRCP, FACP, FACG, Department of Gastroenterology, Kaiser Permanente Medical Center, 6600 Bruceville Road, Sacramento, CA 95823, United States; Dr. Shivananda Nayak, PhD, Department of Preclinical Sciences, Biochemistry Unit, Faculty of Medical Sciences, The University of The West Indies, Building 36, EWMSC, Mount Hope, Trinidad and Tobago

S- Editor Tian L L- Editor Ma JY E- Editor Ma WH

| 1. | Casais MN, Rosa-Diez G, Pérez S, Mansilla EN, Bravo S, Bonofiglio FC. Hyperphosphatemia after sodium phosphate laxatives in low risk patients: prospective study. World J Gastroenterol. 2009;15:5960-5965. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 2. | Ehrenpreis ED. Increased serum phosphate levels and calcium fluxes are seen in smaller individuals after a single dose of sodium phosphate colon cleansing solution: a pharmacokinetic analysis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2009;29:1202-1211. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 3. | Ehrenpreis ED, Varala K, Hammon B. Lower weight is a risk factor for calcium phosphate nephropathy with sodium phosphate colonoscopy preparation: a simulation study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2008;103:S408-S455. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 4. | Parakkal D, Ehrenpreis ED. Calcium phosphate nephropathy from colonoscopy preparations: effect of body weight. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010;105:705. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 5. | Pelham R, Dobre A, Van Diest K, Cleveland MVB. Oral sodium phosphate bowel preparations: How much hydration is enough? Gastrointest Endosc. 2007;65:AB314. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 6. | Patel V, Emmett M, Santa Ana CA, Fordtran JS. Pathogenesis of nephrocalcinosis after sodium phosphate catharsis to prepare for colonoscopy: Intestinal phosphate absorption and its effect on urine mineral and electrolyte excretion. Hum Pathol. 2007;38:193-194; author reply 194-195. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 7. | Markowitz GS, Perazella MA. Acute phosphate nephropathy. Kidney Int. 2009;76:1027-1034. [Cited in This Article: ] |