Published online Nov 14, 2009. doi: 10.3748/wjg.15.5249

Revised: October 7, 2009

Accepted: October 14, 2009

Published online: November 14, 2009

The family of mammalian chitinases includes members both with and without glycohydrolase enzymatic activity against chitin, a polymer of N-acetylglucosamine. Chitin is the structural component of fungi, crustaceans, insects and parasitic nematodes, but is completely absent in mammals. Exposure to antigens containing chitin- or chitin-like structures sometimes induces strong T helper type-I responses in mammals, which may be associated with the induction of mammalian chitinases. Chitinase 3-like-1 (CHI3L1), a member of the mammalian chitinase family, is induced specifically during the course of inflammation in such disorders as inflammatory bowel disease, hepatitis and asthma. In addition, CHI3L1 is expressed and secreted by several types of solid tumors including glioblastoma, colon cancer, breast cancer and malignant melanoma. Although the exact function of CHI3L1 in inflammation and cancer is still largely unknown, CHI3L1 plays a pivotal role in exacerbating the inflammatory processes and in promoting angiogenesis and remodeling of the extracellular matrix. CHI3L1 may be highly involved in the chronic engagement of inflammation which potentiates development of epithelial tumorigenesis presumably by activating the mitogen-activated protein kinase and the protein kinase B signaling pathways. Anti-CHI3L1 antibodies or pan-chitinase inhibitors may have the potential to suppress CHI3L1-mediated chronic inflammation and the subsequent carcinogenic change in epithelial cells.

- Citation: Eurich K, Segawa M, Toei-Shimizu S, Mizoguchi E. Potential role of chitinase 3-like-1 in inflammation-associated carcinogenic changes of epithelial cells. World J Gastroenterol 2009; 15(42): 5249-5259

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v15/i42/5249.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.15.5249

| Location | Disorders | Chitinase type | Ref. |

| Airway | Bacteremia with S. pneumoniae | CHI3L1 | [91,92] |

| Bronchial asthma | CHI3L1, AMCase, Ym1 | [14,38] | |

| COPD | CHI3L1 | [93] | |

| Cystic fibrosis | AMCase, CHIT1 | [94] | |

| Rhinosinusitis | AMCase | [95] | |

| Sarcoidosis | CHIT1 | [96,97] | |

| Blood | Bacterial septicemia | CHI3L1 | [98] |

| Brain | Encephalitis | CHI3L1 | [99,100] |

| Meningitis | CHI3L1 | [99] | |

| Disc/Joint | Intervertebral disc degeneration | CHI3L1 | [101] |

| Juvenile idiopathic arthritis | CHIT1 | [102] | |

| Osteoarthritis, RA | CHI3L1 | [103,104] | |

| Eye | Conjunctivitis | AMCase | [105,106] |

| GI tract | Helicobacter gastritis | CHI3L1, CHIT1 | [107,108] |

| Inflammatory bowel disease | CHI3L1 | [10,109] | |

| Heart | Acute myocardial infarction | CHI3L3, CHI3L1 | [110,111,112] |

| Coronary artery disease | CHIT | [113] | |

| Liver | Chronic hepatitis C, LC | CHI3L1 | [114,115] |

| Fatty liver disease | CHIT1 | [116,117] | |

| Hepatic fibrosis | CHI3L1 | [118] | |

| Oral cavity | Periodontitis | Chitinase | [119,120] |

| Systemic | Gaucher disease | CHIT1 | [27] |

| Systemic sclerosis | CHI3L1 | [121,122] |

| Solid tumors | Location | Ref. |

| Glioma, Oligodendroglioma, glioblastoma | Brain | [74,123-132] |

| Squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck | Head and neck | [18,22,62] |

| Lung cancer (small cell carcinoma) | Lung | [133,134] |

| Breast cancer | Breast | [4,8,21,55,57,62,67,68,75,132-141] |

| Colorectal cancer | Colon | [20,132] |

| Kidney tumor | Kidney | [132,142,143] |

| Hepatocellular carcinoma | Liver | [21,66] |

| Ovarian tumor, endometrial cancer | Ovary | [55-61,133,138,139] |

| Primary prostate cancer | Prostate | [23,63,144] |

| Metastatic prostate cancer | ||

| Papilloma thyroid carcinoma, thyroid tumor | Thyroid | [136,145] |

| Extracellular myxoid-chondrosarcoma | Bone | [146] |

| Multiple myeloma | Bone marrow | [147,148] |

| Hodgkin’s lymphoma | Lymph node | [65] |

| Malignant melanoma | Melanocyte | [18,64] |

| Myxoid liposarcoma | Fat cells | [146] |

| Inflammatory disorder | Carcinogenic formation | Ref. |

| Human papillomavirus infection | Cervical carcinoma | [149-152] |

| Crohn’s disease, ulcerative colitis | Colorectal carcinoma | [153-159] |

| Chronic cholecystitis | Gall bladder carcinoma | [160-162] |

| Hepatitis B, C infection | Hepatocellular carcinoma | [163-167] |

| Asbestosis, asthma, C. pneumoniae infection, chronic obstructive lung disease, middle lobe syndrome, silicosis | Lung carcinoma | [168-174] |

| Pelvic inflammatory disease | Ovarian carcinoma | [175-177] |

| Chronic pancreatitis | Pancreatic carcinoma | [178-183] |

| H pylori infected gastritis | Gastric carcinoma, lymphoma | [184-186] |

| Chronic cystitis, schistosomiasis | Bladder carcinoma | [187-190] |

| Primary sclerosing cholangitis | Cholangio carcinoma, colorectal carcinoma, liver carcinoma, pancreatic carcinoma | [191] |

Chitin, the linear polymer of β-1,4-linked N-acetylglucosamine (GlcNAc), is a structural component of the cell walls and coatings of many organisms, and represents the second most abundant polysaccharide in nature after cellulose. Chitin efficiently protects crustaceans, insects, parasites, fungi, and other pathogens from the harsh adverse effects of their environments and/or hosts[1]. Although chitin has not been found in mammals, several mammalian proteins with homology to fungal, bacterial, or plant chitinases have been identified[2-6]. Chitotriosidase (CHIT1), and acidic mammalian chitinase (AMCase) are the only 2 of these proteins demonstrating chitinolytic (glycohydrolase) activity, while none of the other mammalian chitinases show enzymatic activity despite the retention and conservation of the substrate-binding cleft of the chitinases[7-9]. Therefore, the latter chitinases are called chitinase-like-lectins (Chi-lectins). Only recently, our group and others have identified the important biological roles of mammalian chitinases in chronic inflammatory conditions including inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), type 2 diabetes, proliferative dermatitis and allergic bronchial asthma[10-16]. One mammalian chitinase, chitinase 3-like-1 (CHI3L1, also known as YKL-40 or HC-gp39) is overexpressed in many pathological conditions including fibroblastic change in liver cirrhosis, increased deposition of connective tissue components and hyperplastic synovium in rheumatoid arthritis, and increased cellular infiltration as well as epithelial proliferation in chronic colitis. CHI3L1 is difficult to detect in the body of normal individuals and the biological role of CHI3L1 in embryonic development or distribution of this molecule in normal tissues is still largely unclear. Interestingly, significantly high amounts of CHI3L1 are detected in the involuting mammary gland upon cessation of lactation[2], however the exact biological role of CHI3L1 in this process has not yet been elucidated. CHI3L1 can also directly regulate the critical processes of adhesion and migration in vascular smooth muscle cells in vitro[17]. In addition many groups have reported that CHI3L1 is expressed on many different types of human solid cancers[3,10,18,19]. Surprisingly, CHI3L1 seems to be a useful “prognosticator”, or indicator of prognosis, and may also be a potential “tumor marker” in screening and monitoring of cancer patients[20-23]. In this review article, we will discuss the potentially important biological functions of mammalian chitinases, in particular CHI3L1, during the development of chronic inflammation and the subsequent inflammation-mediated oncogenic processes in epithelial cells.

Chitin, a polymer of GlcNAc, is produced copiously by a wide variety of organisms such as crustaceans (e.g. shrimp and crab), insects, fungi, amphibians, parasitic nematodes, and other marine organisms[24,25]. However, chitin is completely absent in mammals including humans and mice[26]. Therefore, it was believed for a long time that mammals were not capable of producing chitinolytic endoglucosaminases in the body, but Hollak et al[27] first discovered CHIT1, a functional and structural homolog to the chitinases of other species, in serum samples of Gaucher disease patients. Gaucher disease is a genetic disorder causing a lack of the lysosomal enzyme glucocerebrosidase and is characterized by accumulation of macrophage-like Gaucher cells which have glycosphingolipids in cytosolic compartments[28]. The serum level of CHIT1 is upregulated approximately 1000-fold in patients with Gaucher disease as compared to normal individuals and the enzyme shows glycohydrolase activity against chitin and other chitin-like substances (e.g. p-nitrophenyl chitooligosaccharides)[29]. Subsequent studies revealed that the increased CHIT1 activity in Gaucher disease patients is associated with aberrant macrophage activation[28], and the activity can be used as a marker of disease severity and therapeutic response in Gaucher disease[30]. Boot et al[31] reported that approximately 6% of various ethnic groups have a homozygous mutant allele of 24 bp duplication of the CHIT1 gene, resulting in a complete lack of CHIT1 enzymatic activity. Increased rates of nematode infection seemed to be associated with the mutation[32]. The CHIT1 cDNA was cloned by Boot et al[33] revealing that this molecule has a strong sequential homology to other chitinases belonging to the family 18 of glycosyl hydrolases. CHIT1 contains a complete chitin-binding domain in the C-terminus region that connects with the catalytic groove by a hinge region[34]. The chitin-binding domain of CHIT1 efficiently binds with chitin polymers as shown by structural analysis[35]. Under inflammatory conditions, CHIT1 expression of pathogenic macrophages is significantly upregulated in the inflamed tissues[29]. In addition to CHIT1, there is another mammalian chitinase, AMCase, which shows high structural homology with CHIT1, has an optimal enzymatic activity at around pH2 and exhibits glycohydrolase enzymatic activity. Full-length cDNA of mouse and human AMCase was first cloned in 2001[36], but an exciting biological role of AMCase was revealed by Zhu et al[14] only recently: the group noticed a formation of crystals in lung tissues of mice with an asthma-like disease model and identified that the crystals were mammalian chitinase[37]. The same group further identified that overproduction of AMCase is highly dependent on a Th2 cytokine IL-13, which further induces production of IP-10 [interferon (IFN)-inducible protein-10] and ITAC (IFN-inducible T cell alpha chemoattractant)[14]. The production of AMCase was significantly upregulated in the epithelial cells and tissue macrophages of patients with asthma, but the expression at messenger RNA level was undetectable from patients without lung disease[14,37]. Interestingly, anti-AMCase specific antibody as well as pan-chitinase inhibitor allosamidin efficiently ameliorate airway hyperresponsiveness and inflammatory cell infiltrations in the lung of aeroallergen-challenged mice[14], suggesting that AMCase would be an attractive therapeutic target in allergic asthma. A common genetic variant within exon 4 of AMCase from A to G at position 47 (termed A47G) and another variant K17R showed significant association with pediatric asthma. These genetic results support strongly that AMCase is associated with the development of asthma. Recently, Elias’s group found that not only AMCase but also CHI3L1 levels in serum as well as lung tissue were significantly elevated in 3 cohorts of patient (at Yale University, University of Paris, and University of Wisconsin) with asthma[15]. Expression levels of CHI3L1 in the serum and lungs closely correlated with the severity of asthma, suggesting that the CHI3L1 molecule plays both a primary and a secondary role in asthma patients[15]. In addition, another group also identified that a promoter single nucleotide polymorphism (C131G) in CHI3L1 was strongly associated with elevated serum levels of CHI3L1, pulmonary function, asthma, and bronchial hyperresponsiveness[38]. From those results, it appears mammalian chitinases are somehow associated with the development of inflammatory conditions in mucosal tissues. The association between the mammalian chitinases and inflammatory disorders is summarized in Table 1.

Although CHI3L1 was first identified in 1993[3], its biological function has been largely undetermined. CHI3L1 possesses a functional carbohydrate-binding motif which allows binding with a polymer or oligomer of GlcNAc, but CHI3L1 lacks enzymatic activity entirely. The lack of enzymatic activity in CHI3L1 can be explained by the substitution of leucine for an essential glutamic acid residue within the active site of CHI3L1[39]. Therefore, chitinases without enzymatic activity (including CHI3L1) act as chi-lectin[40] because of the presence of a preserved carbohydrate-binding motif. Recently, Recklies et al[39] reported that CHI3L1 promotes the growth of human synovial cells and fibroblasts, raising the possibility that this protein plays a role in the pathological conditions leading to arthritis and tissue fibrosis. Of note, increased circulating levels of CHI3L1 have been reported in the serum of patients with several inflammatory conditions including IBD [Crohn’s disease (CD) and ulcerative colitis (UC)][41], asthma[15,38] and liver cirrhosis[42]. Serum CHI3L1 is rarely detectable in healthy individuals[41], and therefore CHI3L1 has recently been proposed as a useful marker for indicating inflammatory activity and poor clinical prognosis for IBD[41]. A soluble form of CHI3L1 seems to be secreted by a wide variety of mammalian cells in vitro, including activated neutrophils, granulocytes, differentiated macrophages and colonic epithelial cells (CECs)[10,19,43]. CHI3L1 is strongly expressed by macrophages in the synovial membrane of patients with rheumatoid arthritis (RA) and a polarized IFNγ-mediated proinflammatory Th1-type immune response has been observed in half the patients with RA. In contrast, peripheral mononuclear cells from healthy individuals strongly react against the CHI3L1 antigen and eventually produce a regulatory cytokine IL-10[44]. These results strongly suggest that CHI3L1-mediated immune responses in RA patients are somehow shifted from an IL-10 dominated immunoregulatory response to an IFNγ-dominated proinflammatory phenotype[44]. In addition, serum levels of CHI3L1 are positively correlated with the severity of arthritis[45]. Interestingly, peripheral blood T cells from RA patients proliferate in response to RA-associated DR4 (DRB1*0401) peptide which contains a potential self-reactive motif preserved within human CHI3L1[46]. In fact, the specific motif within CHI3L1 is responsible for the development and relapse of joint inflammation seen in Balb/c mice, suggesting that CHI3L1 is able to serve as an auto-antigen for arthritis in mice as well as humans[46]. Intranasal as well as oral auto-antigen administration is one of the most effective strategies for inducing immuno-tolerance[47,48]. Indeed, several groups have tried to administer CHI3L1 intranasally in animal models of arthritis[49,50] as well as RA patients with moderate disease activity[51], and the protein administration effectively suppresses the disease activity by downregulating the Th1-type immune response without showing any adverse effects. Therefore, CHI3L1 seems to be the cross-tolerance inducing protein in chronic arthritis which effectively downregulates the pathogenic immune responses. It is possible that nasal administration of CHI3L1 represents an attractive approach for suppressing the clinical manifestation of chronic types of inflammation as well as autoimmune diseases.

Our group recently identified that CHI3L1 plays a unique role during the development of intestinal inflammation: the molecule is induced in both colonic lamina propria macrophages and CECs during the course of intestinal inflammation in experimental colitis models as well as in patients with IBD[10]. Gentamicin protection assays using intracellular bacteria, including Salmonella typhimurium and adherent invasive Escherichia coli show that CHI3L1 is required for the enhancement of adhesion and invasion of these bacteria on/into CECs and acts as a pathogenic mediator in acute colitis. It has been suggested that a genetic defect against intracellular bacterial infection is strongly associated with the development of CD, and an increased prevalence of intracellular bacteria in the ileal biopsies and surgical specimens of CD patients has been reported previously[52,53]. We also identified that the CHI3L1 molecule particularly enhances the adhesion of chitin-binding protein-expressing bacteria to CECs through the conserved amino-acid residues[11]. Therefore, overexpression of CHI3L1 may be strongly associated with the intracellular bacterial adhesion and invasion on/into CECs in CD patients, who presumably have mutations in the susceptibility genes of CD including NOD2 (CARD 15), IL-23R, ATG16L1 and XBP-1[54]. In contrast, in an aseptic condition such as bronchial asthma, epithelium-expressing CHI3L1 seems to play a regulatory role by rescuing Th2-type immune responses[16]. Further study will be required to fully prove the exact role of epithelium-expressing CHI3L1 in inflammatory conditions.

The biological function of CHI3L1 is still unclear, but it has been strongly hypothesized that CHI3L1 plays a pivotal role as a growth stimulating factor for solid tumors or has a suppressive/protective effect in the apoptotic processes of cancer cells[18] and inflammatory cells[16]. Based on an amino acid database search at the National Center for Biotechnology Information, CHI3L1 is expressed in a wide variety of human solid tumors as summarized in Table 2. In addition, elevated levels of CHI3L1 in serum and/or plasma have been detected in patients with different types of solid tumors (Table 2). Therefore, it is reasonable to predict that the serum level of CHI3L1 can be a reliable marker of progression of certain kinds of tumors and of a “bad prognosis” in patients with certain types of malignant tumors[18].

Many clinical laboratories have reported that CHI3L1 could be used as a novel tumor marker for ovarian cancer[55,56], small cell lung cancer[22], metastatic breast cancer[57], and metastatic prostate cancer[23]. In addition, several groups have reported that CHI3L1 is one of the most significant prognosis markers for cervical adenocarcinoma[58], recurrent breast cancer[4] and metastatic breast cancer[21], as well as advanced stages of breast cancer[59]. Interestingly, the CHI3L1 serum level could be a useful and sensitive biomarker for recurrence in locally advanced breast carcinoma[59], ovarian carcinoma[60], endometrial cancer[61], squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck[62], metastatic prostate cancer or melanoma[63,64], Hodgkin’s lymphoma[65] and colon cancer[20]. Based on extensive research by Johansen and colleagues, CHI3L1 may be used as a novel and sensitive predictor of any cancer[66,67]. They categorized patients into 5 distinct levels according to the amount of plasma CHI3L1 detected by ELISA, and found that participants with the highest level of plasma CHI3L1 had a median survival rate of only 1 year after the cancer diagnosis[66]. In contrast, the patients with the lowest level of plasma CHI3L1 had a survival rate of more than 4 years. Although the variation of CHI3L1 serum levels in healthy subjects in this study was relatively small, subsequent measurements would be required to determine cancer risk since the serum level of CHI3L1 could also be elevated in patients with other inflammatory diseases or autoimmune disorders[68]. From the results, it has been highly predicted that serum CHI3L1 levels seem to be a potential and promising biomarker for malignant tumors.

The expression of CHI3L1 is relatively restricted to a limited number of cell types: it is totally absent in monocytes[69] and marginally expressed in monocyte-derived dendritic cells[70], but is strongly induced during the late stages of human macrophage differentiation[43]. Rehli et al[43] clearly demonstrated that promoter elements (in particular, the proximal -377 base pairs of the CHI3L1 promoter region) control the expression of CHI3L1 in the macrophage used. CHI3L1 is also expressed in neutrophils[71], chondrocytes[3], fibroblast-like synoviocytes[72], vascular smooth muscle cells[5], vascular endothelial cells[73], ductal epithelial cells[67], hepatic stellate cells[18], and colonic epithelial cells[10]. In physiological concentrations CHI3L1 tends to promote proliferation of these cell types. CHI3L1 is a transmembrane protein whose extracellular domain can undergo cleavage[39]. The cleavaged components bind to putative receptor(s) on the cell surface or soluble receptor(s), but these receptors have not been identified yet[18,40]. Some reports suggest that CHI3L1 can play an important role in tumor invasion. Nigro et al[74] showed that immortalized human astrocytes stably transfected with CHI3L1 increased invasion across a chemotactic gradient in vitro. Roslind et al[75] demonstrated that metastatic tumor cells in blood vessels, lymph nodes and skin displayed the same pattern of CHI3L1 as primary breast cancer cells by immunohistochemical analysis: normal epithelial cells display the widespread strong dot-like staining in the whole cytoplasm, while the dot-like staining is localized in the restricted area of cytoplasma in malignant tumor cells. Indeed, CHI3L1 is strongly expressed in the invasive front of lobular carcinoma which is adjacent to normal epithelial cells. These studies suggest that CHI3L1 may assist the migration of malignant cells and support metastasis of cancer cells by promoting the malignant transformation of adjacent normal epithelial cells.

It has been predicted that CHI3L1 can have a growth stimulating effect since a family of CHI3L molecules in the fruit fly Drosophila melanogaster regulates the growth of imaginal disc cells[76]. Two of the major biological functions of CHI3L1 are a growth stimulating effect on connective tissue cells[39,72] and a potent migration enhancing effect for endothelial cells[73]. CHI3L1 also stimulates angiogenesis and reorganization of vascular endothelial cells[73]. Insulin-like growth factor-1 is a well-characterized growth factor in connective tissue cells, and works synergistically with CHI3L1 to enhance the response of human synovial cells isolated from patients with osteoarthritis[39]. In addition, CHI3L1 strongly promotes the activation of 2 major signaling pathways associated with mitogenesis and cell survival: MAPK (mitogen-activated protein kinase) pathways and PI-3K (phosphoinositide 3-kinase)-mediated pathways in fibroblast cells. The putative cell surface receptor and/or adaptive molecule for CHI3L1 are still unidentified, but the purified human CHI3L1 molecule efficiently leads to phosphorylation of MAPK p42/p44 in human synovial cells, fibroblasts, articular chondrocytes[39] and human colonic epithelial cells (Mizoguchi E, unpublished observation) in a dose-dependent manner. It has been suggested that guanine nucleotide-binding protein (G-protein)-regulated MAPK networks are involved in the action of most non-nuclear oncogenes and subsequent carcinogenesis and tumor progression[77]. The networks are involved in the activation of MAPK p42/p44 which may enhance the carcinogenic change of epithelial cells during upregulated CHI3L1 expression under inflammatory conditions.

It is believed that IBD is a risk factor of cancer development based on the severity of the disease course. As previously reported, serum CHI3L1 concentration is elevated in patients with IBD[41] and primary colorectal cancer[20]. People with CD have a 5.6-fold increased risk of developing colon cancer[78]; therefore screening for colon cancer by colonoscopy is strongly recommended for patients who have had CD for several years[79]. Inflammation was recently recognized as an important factor in the pathogenesis of malignant tumors[80] and we summarize some examples of inflammation-mediated carcinogenesis in Table 3. Of interest, most of the diseases listed in Table 3 express CHI3L1 during the course of inflammation and the subsequent tumorigenesis. CHI3L1 protects cancer cells from undergoing apoptosis and also has an effect on extracellular tissue remodeling by binding specifically with collagen types I, II, and III[81]. Therefore, CHI3L1 is strongly associated with cell survival and cell migration during the drastic tissue remodeling processes by interacting with extracellular matrix components[39,40].

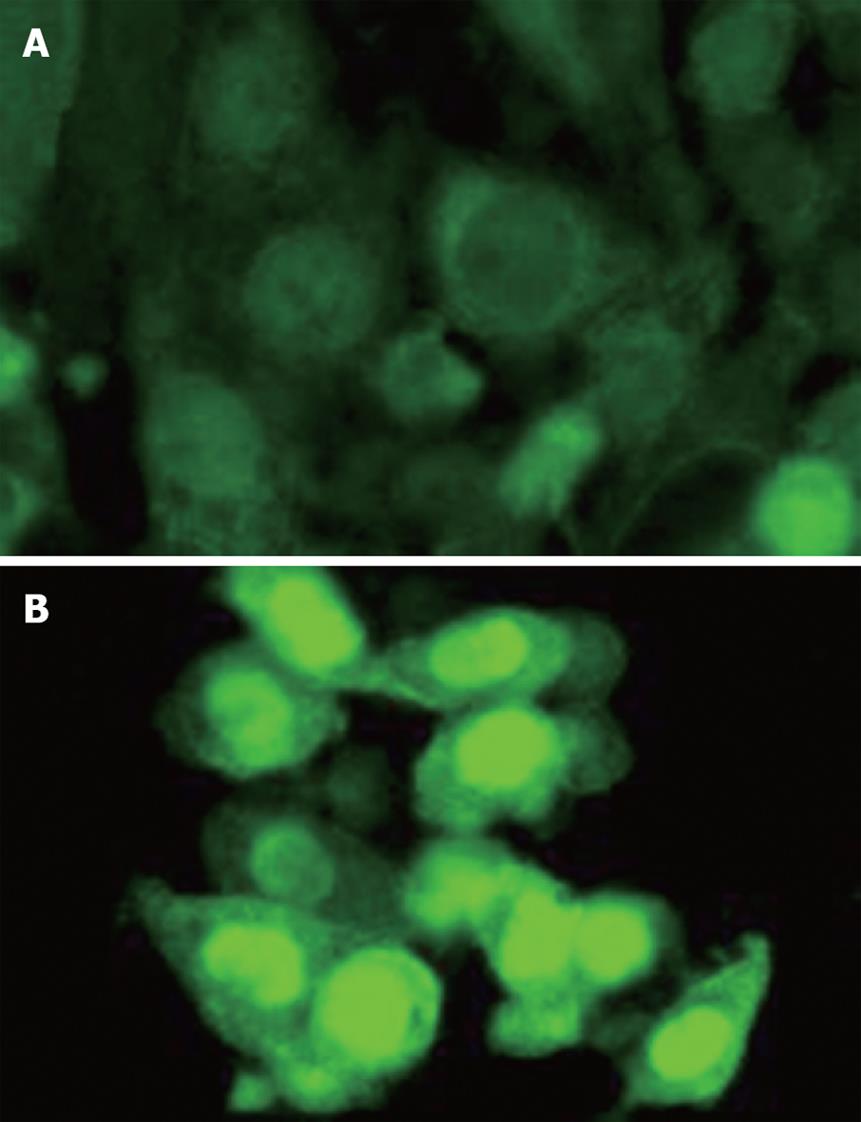

The canonical (Wnt/β-catenin) pathway is known to play a crucial role in UC-related tumor progression[82]. Recently, our group identified that the SW480 human colon cancer cell line shows significantly upregulated expression and trans-nucleic translocation of β-catenin after extensive stimulation with low dose (50 ng/mL) purified CHI3L1 protein (Quidel, San Diego, CA) (Figure 1). This result strongly suggests that CHI3L1 may have a direct but not a secondary role for inflammation-associated tumorigenesis by continuously activating the Wnt/β-catenin canonical signaling pathway in CECs. As previously demonstrated, CHI3L1 expression is enhanced by proinflammatory cytokine interleukin-6[10,83], which also has a critical tumor-promoting effect during early colitis-associated cancer tumorigenesis[84]. It has been proven that activation of gp130/STAT3 transcription factor regulates cell cycle progression as well as survival of enterocytes during chronic colitis-associated tumor promotion[85-88]. Therefore, the blocking of interleukin-6 mediated CHI3L1 expression by anti-CHI3L1 specific antibody or pan-family 18 chitinase inhibitors including allosamidin and methylxanthine derivatives (e.g. theophylline, caffeine, and pentoxifylline)[14,89,90] would be a useful strategy in preventing both chronic mucosal inflammation and the subsequent inflammation-associated carcinogenic change in epithelial cells. In summary, CHI3L1 could be a useful and attractive target for potential anti-cancer therapies, in particular against highly invasive and metastatic solid tumors.

Mammalian chitinases, including CHI3L1 and AMCase, actively participate in the pathogenesis of acute and chronic inflammation and presumably the following inflammation-associated tumorigenesis. Further understanding of the biological and physiological functions of mammalian chitinases would be very important to develop novel anti-inflammatory as well as anti-cancer therapies for several inflammatory disorders and inflammation-associated cancers in the near future.

Peer reviewer: Jay Pravda, MD, Inflammatory Disease Research Center, Gainesville, Florida 32614-2181, United States

S- Editor Tian L L- Editor Cant MR E- Editor Lin YP

| 1. | Herrera-Estrella A, Chet I. Chitinases in biological control. EXS. 1999;87:171-184. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 2. | Rejman JJ, Hurley WL. Isolation and characterization of a novel 39 kilodalton whey protein from bovine mammary secretions collected during the nonlactating period. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1988;150:329-334. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 3. | Hakala BE, White C, Recklies AD. Human cartilage gp-39, a major secretory product of articular chondrocytes and synovial cells, is a mammalian member of a chitinase protein family. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:25803-25810. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 4. | Johansen JS, Cintin C, Jørgensen M, Kamby C, Price PA. Serum YKL-40: a new potential marker of prognosis and location of metastases of patients with recurrent breast cancer. Eur J Cancer. 1995;31A:1437-1442. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 5. | Shackelton LM, Mann DM, Millis AJ. Identification of a 38-kDa heparin-binding glycoprotein (gp38k) in differentiating vascular smooth muscle cells as a member of a group of proteins associated with tissue remodeling. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:13076-13083. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 6. | Hu B, Trinh K, Figueira WF, Price PA. Isolation and sequence of a novel human chondrocyte protein related to mammalian members of the chitinase protein family. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:19415-19420. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 7. | Perrakis A, Tews I, Dauter Z, Oppenheim AB, Chet I, Wilson KS, Vorgias CE. Crystal structure of a bacterial chitinase at 2.3 A resolution. Structure. 1994;2:1169-1180. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 8. | van Aalten DM, Komander D, Synstad B, Gåseidnes S, Peter MG, Eijsink VG. Structural insights into the catalytic mechanism of a family 18 exo-chitinase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:8979-8984. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 9. | Sun YJ, Chang NC, Hung SI, Chang AC, Chou CC, Hsiao CD. The crystal structure of a novel mammalian lectin, Ym1, suggests a saccharide binding site. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:17507-17514. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 10. | Mizoguchi E. Chitinase 3-like-1 exacerbates intestinal inflammation by enhancing bacterial adhesion and invasion in colonic epithelial cells. Gastroenterology. 2006;130:398-411. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 11. | Kawada M, Chen CC, Arihiro A, Nagatani K, Watanabe T, Mizoguchi E. Chitinase 3-like-1 enhances bacterial adhesion to colonic epithelial cells through the interaction with bacterial chitin-binding protein. Lab Invest. 2008;88:883-895. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 12. | Rathcke CN, Johansen JS, Vestergaard H. YKL-40, a biomarker of inflammation, is elevated in patients with type 2 diabetes and is related to insulin resistance. Inflamm Res. 2006;55:53-59. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 13. | HogenEsch H, Dunham A, Seymour R, Renninger M, Sundberg JP. Expression of chitinase-like proteins in the skin of chronic proliferative dermatitis (cpdm/cpdm) mice. Exp Dermatol. 2006;15:808-814. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 14. | Zhu Z, Zheng T, Homer RJ, Kim YK, Chen NY, Cohn L, Hamid Q, Elias JA. Acidic mammalian chitinase in asthmatic Th2 inflammation and IL-13 pathway activation. Science. 2004;304:1678-1682. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 15. | Chupp GL, Lee CG, Jarjour N, Shim YM, Holm CT, He S, Dziura JD, Reed J, Coyle AJ, Kiener P. A chitinase-like protein in the lung and circulation of patients with severe asthma. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:2016-2027. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 16. | Lee CG, Hartl D, Lee GR, Koller B, Matsuura H, Da Silva CA, Sohn MH, Cohn L, Homer RJ, Kozhich AA. Role of breast regression protein 39 (BRP-39)/chitinase 3-like-1 in Th2 and IL-13-induced tissue responses and apoptosis. J Exp Med. 2009;206:1149-1166. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 17. | Nishikawa KC, Millis AJ. gp38k (CHI3L1) is a novel adhesion and migration factor for vascular cells. Exp Cell Res. 2003;287:79-87. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 18. | Johansen JS. Studies on serum YKL-40 as a biomarker in diseases with inflammation, tissue remodelling, fibroses and cancer. Dan Med Bull. 2006;53:172-209. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 19. | Volck B, Ostergaard K, Johansen JS, Garbarsch C, Price PA. The distribution of YKL-40 in osteoarthritic and normal human articular cartilage. Scand J Rheumatol. 1999;28:171-179. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 20. | Cintin C, Johansen JS, Christensen IJ, Price PA, Sørensen S, Nielsen HJ. High serum YKL-40 level after surgery for colorectal carcinoma is related to short survival. Cancer. 2002;95:267-274. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 21. | Jensen BV, Johansen JS, Price PA. High levels of serum HER-2/neu and YKL-40 independently reflect aggressiveness of metastatic breast cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2003;9:4423-4434. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 22. | Johansen JS, Drivsholm L, Price PA, Christensen IJ. High serum YKL-40 level in patients with small cell lung cancer is related to early death. Lung Cancer. 2004;46:333-340. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 23. | Brasso K, Christensen IJ, Johansen JS, Teisner B, Garnero P, Price PA, Iversen P. Prognostic value of PINP, bone alkaline phosphatase, CTX-I, and YKL-40 in patients with metastatic prostate carcinoma. Prostate. 2006;66:503-513. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 24. | Debono M, Gordee RS. Antibiotics that inhibit fungal cell wall development. Annu Rev Microbiol. 1994;48:471-497. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 25. | Donnelly LE, Barnes PJ. Acidic mammalian chitinase--a potential target for asthma therapy. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2004;25:509-511. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 26. | Siaens R, Eijsink VG, Dierckx R, Slegers G. (123)I-Labeled chitinase as specific radioligand for in vivo detection of fungal infections in mice. J Nucl Med. 2004;45:1209-1216. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 27. | Hollak CE, van Weely S, van Oers MH, Aerts JM. Marked elevation of plasma chitotriosidase activity. A novel hallmark of Gaucher disease. J Clin Invest. 1994;93:1288-1292. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 28. | Boven LA, van Meurs M, Boot RG, Mehta A, Boon L, Aerts JM, Laman JD. Gaucher cells demonstrate a distinct macrophage phenotype and resemble alternatively activated macrophages. Am J Clin Pathol. 2004;122:359-369. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 29. | Aguilera B, Ghauharali-van der Vlugt K, Helmond MT, Out JM, Donker-Koopman WE, Groener JE, Boot RG, Renkema GH, van der Marel GA, van Boom JH. Transglycosidase activity of chitotriosidase: improved enzymatic assay for the human macrophage chitinase. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:40911-40916. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 30. | Barone R, Sotgiu S, Musumeci S. Plasma chitotriosidase in health and pathology. Clin Lab. 2007;53:321-333. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 31. | Boot RG, Renkema GH, Verhoek M, Strijland A, Bliek J, de Meulemeester TM, Mannens MM, Aerts JM. The human chitotriosidase gene. Nature of inherited enzyme deficiency. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:25680-25685. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 32. | Choi EH, Zimmerman PA, Foster CB, Zhu S, Kumaraswami V, Nutman TB, Chanock SJ. Genetic polymorphisms in molecules of innate immunity and susceptibility to infection with Wuchereria bancrofti in South India. Genes Immun. 2001;2:248-253. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 33. | Boot RG, Renkema GH, Strijland A, van Zonneveld AJ, Aerts JM. Cloning of a cDNA encoding chitotriosidase, a human chitinase produced by macrophages. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:26252-26256. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 34. | Fusetti F, von Moeller H, Houston D, Rozeboom HJ, Dijkstra BW, Boot RG, Aerts JM, van Aalten DM. Structure of human chitotriosidase. Implications for specific inhibitor design and function of mammalian chitinase-like lectins. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:25537-25544. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 35. | Davies GJ, Mackenzie L, Varrot A, Dauter M, Brzozowski AM, Schülein M, Withers SG. Snapshots along an enzymatic reaction coordinate: analysis of a retaining beta-glycoside hydrolase. Biochemistry. 1998;37:11707-11713. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 36. | Boot RG, Blommaart EF, Swart E, Ghauharali-van der Vlugt K, Bijl N, Moe C, Place A, Aerts JM. Identification of a novel acidic mammalian chitinase distinct from chitotriosidase. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:6770-6778. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 37. | Elias JA, Homer RJ, Hamid Q, Lee CG. Chitinases and chitinase-like proteins in T(H)2 inflammation and asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2005;116:497-500. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 38. | Ober C, Tan Z, Sun Y, Possick JD, Pan L, Nicolae R, Radford S, Parry RR, Heinzmann A, Deichmann KA. Effect of variation in CHI3L1 on serum YKL-40 level, risk of asthma, and lung function. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:1682-1691. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 39. | Recklies AD, White C, Ling H. The chitinase 3-like protein human cartilage glycoprotein 39 (HC-gp39) stimulates proliferation of human connective-tissue cells and activates both extracellular signal-regulated kinase- and protein kinase B-mediated signalling pathways. Biochem J. 2002;365:119-126. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 40. | Ling H, Recklies AD. The chitinase 3-like protein human cartilage glycoprotein 39 inhibits cellular responses to the inflammatory cytokines interleukin-1 and tumour necrosis factor-alpha. Biochem J. 2004;380:651-659. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 41. | Vind I, Johansen JS, Price PA, Munkholm P. Serum YKL-40, a potential new marker of disease activity in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2003;38:599-605. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 42. | Johansen JS, Møller S, Price PA, Bendtsen F, Junge J, Garbarsch C, Henriksen JH. Plasma YKL-40: a new potential marker of fibrosis in patients with alcoholic cirrhosis? Scand J Gastroenterol. 1997;32:582-590. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 43. | Rehli M, Niller HH, Ammon C, Langmann S, Schwarzfischer L, Andreesen R, Krause SW. Transcriptional regulation of CHI3L1, a marker gene for late stages of macrophage differentiation. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:44058-44067. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 44. | van Bilsen JH, van Dongen H, Lard LR, van der Voort EI, Elferink DG, Bakker AM, Miltenburg AM, Huizinga TW, de Vries RR, Toes RE. Functional regulatory immune responses against human cartilage glycoprotein-39 in health vs. proinflammatory responses in rheumatoid arthritis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:17180-17185. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 45. | Johansen JS, Jensen HS, Price PA. A new biochemical marker for joint injury. Analysis of YKL-40 in serum and synovial fluid. Br J Rheumatol. 1993;32:949-955. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 46. | Verheijden GF, Rijnders AW, Bos E, Coenen-de Roo CJ, van Staveren CJ, Miltenburg AM, Meijerink JH, Elewaut D, de Keyser F, Veys E. Human cartilage glycoprotein-39 as a candidate autoantigen in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 1997;40:1115-1125. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 47. | Eriksson K, Holmgren J. Recent advances in mucosal vaccines and adjuvants. Curr Opin Immunol. 2002;14:666-672. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 48. | Iweala OI, Nagler CR. Immune privilege in the gut: the establishment and maintenance of non-responsiveness to dietary antigens and commensal flora. Immunol Rev. 2006;213:82-100. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 49. | Wolvers DA, Coenen-de Roo CJ, Mebius RE, van der Cammen MJ, Tirion F, Miltenburg AM, Kraal G. Intranasally induced immunological tolerance is determined by characteristics of the draining lymph nodes: studies with OVA and human cartilage gp-39. J Immunol. 1999;162:1994-1998. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 50. | Joosten LA, Coenen-de Roo CJ, Helsen MM, Lubberts E, Boots AM, van den Berg WB, Miltenburg AM. Induction of tolerance with intranasal administration of human cartilage gp-39 in DBA/1 mice: amelioration of clinical, histologic, and radiologic signs of type II collagen-induced arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2000;43:645-655. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 51. | Zandbelt MM, Houbiers JG, van den Hoogen FH, Meijerink J, van Riel PL, in't Hout J, van de Putte LB. Intranasal administration of recombinant human cartilage glycoprotein-39. A phase I escalating cohort study in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. J Rheumatol. 2006;33:1726-1733. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 52. | Darfeuille-Michaud A, Boudeau J, Bulois P, Neut C, Glasser AL, Barnich N, Bringer MA, Swidsinski A, Beaugerie L, Colombel JF. High prevalence of adherent-invasive Escherichia coli associated with ileal mucosa in Crohn's disease. Gastroenterology. 2004;127:412-421. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 53. | Swidsinski A, Ladhoff A, Pernthaler A, Swidsinski S, Loening-Baucke V, Ortner M, Weber J, Hoffmann U, Schreiber S, Dietel M. Mucosal flora in inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterology. 2002;122:44-54. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 54. | Xavier RJ, Podolsky DK. Unravelling the pathogenesis of inflammatory bowel disease. Nature. 2007;448:427-434. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 55. | Dehn H, Høgdall EV, Johansen JS, Jørgensen M, Price PA, Engelholm SA, Høgdall CK. Plasma YKL-40, as a prognostic tumor marker in recurrent ovarian cancer. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2003;82:287-293. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 56. | Høgdall EV, Ringsholt M, Høgdall CK, Christensen IJ, Johansen JS, Kjaer SK, Blaakaer J, Ostenfeld-Møller L, Price PA, Christensen LH. YKL-40 tissue expression and plasma levels in patients with ovarian cancer. BMC Cancer. 2009;9:8. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 57. | Johansen JS, Christensen IJ, Riisbro R, Greenall M, Han C, Price PA, Smith K, Brünner N, Harris AL. High serum YKL-40 levels in patients with primary breast cancer is related to short recurrence free survival. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2003;80:15-21. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 58. | Mitsuhashi A, Matsui H, Usui H, Nagai Y, Tate S, Unno Y, Hirashiki K, Seki K, Shozu M. Serum YKL-40 as a marker for cervical adenocarcinoma. Ann Oncol. 2009;20:71-77. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 59. | Coskun U, Yamac D, Gulbahar O, Sancak B, Karaman N, Ozkan S. Locally advanced breast carcinoma treated with neoadjuvant chemotherapy: are the changes in serum levels of YKL-40, MMP-2 and MMP-9 correlated with tumor response? Neoplasma. 2007;54:348-352. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 60. | Gronlund B, Høgdall EV, Christensen IJ, Johansen JS, Nørgaard-Pedersen B, Engelholm SA, Høgdall C. Pre-treatment prediction of chemoresistance in second-line chemotherapy of ovarian carcinoma: value of serological tumor marker determination (tetranectin, YKL-40, CASA, CA 125). Int J Biol Markers. 2006;21:141-148. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 61. | Diefenbach CS, Shah Z, Iasonos A, Barakat RR, Levine DA, Aghajanian C, Sabbatini P, Hensley ML, Konner J, Tew W. Preoperative serum YKL-40 is a marker for detection and prognosis of endometrial cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 2007;104:435-442. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 62. | Roslind A, Johansen JS, Christensen IJ, Kiss K, Balslev E, Nielsen DL, Bentzen J, Price PA, Andersen E. High serum levels of YKL-40 in patients with squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck are associated with short survival. Int J Cancer. 2008;122:857-863. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 63. | Johansen JS, Brasso K, Iversen P, Teisner B, Garnero P, Price PA, Christensen IJ. Changes of biochemical markers of bone turnover and YKL-40 following hormonal treatment for metastatic prostate cancer are related to survival. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13:3244-3249. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 64. | Schmidt H, Johansen JS, Gehl J, Geertsen PF, Fode K, von der Maase H. Elevated serum level of YKL-40 is an independent prognostic factor for poor survival in patients with metastatic melanoma. Cancer. 2006;106:1130-1139. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 65. | Biggar RJ, Johansen JS, Smedby KE, Rostgaard K, Chang ET, Adami HO, Glimelius B, Molin D, Hamilton-Dutoit S, Melbye M. Serum YKL-40 and interleukin 6 levels in Hodgkin lymphoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14:6974-6978. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 66. | Johansen JS, Bojesen SE, Mylin AK, Frikke-Schmidt R, Price PA, Nordestgaard BG. Elevated plasma YKL-40 predicts increased risk of gastrointestinal cancer and decreased survival after any cancer diagnosis in the general population. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:572-578. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 67. | Qin W, Zhu W, Schlatter L, Miick R, Loy TS, Atasoy U, Hewett JE, Sauter ER. Increased expression of the inflammatory protein YKL-40 in precancers of the breast. Int J Cancer. 2007;121:1536-1542. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 68. | Johansen JS, Pedersen AN, Schroll M, Jørgensen T, Pedersen BK, Bruunsgaard H. High serum YKL-40 level in a cohort of octogenarians is associated with increased risk of all-cause mortality. Clin Exp Immunol. 2008;151:260-266. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 69. | Rehli M, Krause SW, Andreesen R. Molecular characterization of the gene for human cartilage gp-39 (CHI3L1), a member of the chitinase protein family and marker for late stages of macrophage differentiation. Genomics. 1997;43:221-225. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 70. | Krause SW, Rehli M, Kreutz M, Schwarzfischer L, Paulauskis JD, Andreesen R. Differential screening identifies genetic markers of monocyte to macrophage maturation. J Leukoc Biol. 1996;60:540-545. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 71. | Volck B, Price PA, Johansen JS, Sørensen O, Benfield TL, Nielsen HJ, Calafat J, Borregaard N. YKL-40, a mammalian member of the chitinase family, is a matrix protein of specific granules in human neutrophils. Proc Assoc Am Physicians. 1998;110:351-360. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 72. | De Ceuninck F, Gaufillier S, Bonnaud A, Sabatini M, Lesur C, Pastoureau P. YKL-40 (cartilage gp-39) induces proliferative events in cultured chondrocytes and synoviocytes and increases glycosaminoglycan synthesis in chondrocytes. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2001;285:926-931. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 73. | Malinda KM, Ponce L, Kleinman HK, Shackelton LM, Millis AJ. Gp38k, a protein synthesized by vascular smooth muscle cells, stimulates directional migration of human umbilical vein endothelial cells. Exp Cell Res. 1999;250:168-173. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 74. | Nigro JM, Misra A, Zhang L, Smirnov I, Colman H, Griffin C, Ozburn N, Chen M, Pan E, Koul D. Integrated array-comparative genomic hybridization and expression array profiles identify clinically relevant molecular subtypes of glioblastoma. Cancer Res. 2005;65:1678-1686. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 75. | Roslind A, Johansen JS, Junker N, Nielsen DL, Dzaferi H, Price PA, Balslev E. YKL-40 expression in benign and malignant lesions of the breast: a methodologic study. Appl Immunohistochem Mol Morphol. 2007;15:371-381. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 76. | Kawamura K, Shibata T, Saget O, Peel D, Bryant PJ. A new family of growth factors produced by the fat body and active on Drosophila imaginal disc cells. Development. 1999;126:211-219. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 77. | Pearson G, Robinson F, Beers Gibson T, Xu BE, Karandikar M, Berman K, Cobb MH. Mitogen-activated protein (MAP) kinase pathways: regulation and physiological functions. Endocr Rev. 2001;22:153-183. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 78. | Ekbom A, Helmick C, Zack M, Adami HO. Increased risk of large-bowel cancer in Crohn's disease with colonic involvement. Lancet. 1990;336:357-359. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 79. | Collins PD, Mpofu C, Watson AJ, Rhodes JM. Strategies for detecting colon cancer and/or dysplasia in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006;336:CD000279. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 80. | Bromberg J, Wang TC. Inflammation and cancer: IL-6 and STAT3 complete the link. Cancer Cell. 2009;15:79-80. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 81. | Bigg HF, Wait R, Rowan AD, Cawston TE. The mammalian chitinase-like lectin, YKL-40, binds specifically to type I collagen and modulates the rate of type I collagen fibril formation. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:21082-21095. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 82. | van Dekken H, Wink JC, Vissers KJ, Franken PF, Ruud Schouten W, J Hop WC, Kuipers EJ, Fodde R, Janneke van der Woude C. Wnt pathway-related gene expression during malignant progression in ulcerative colitis. Acta Histochem. 2007;109:266-272. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 83. | De Ceuninck F, Pastoureau P, Bouet F, Bonnet J, Vanhoutte PM. Purification of guinea pig YKL40 and modulation of its secretion by cultured articular chondrocytes. J Cell Biochem. 1998;69:414-424. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 84. | Grivennikov S, Karin E, Terzic J, Mucida D, Yu GY, Vallabhapurapu S, Scheller J, Rose-John S, Cheroutre H, Eckmann L. IL-6 and Stat3 are required for survival of intestinal epithelial cells and development of colitis-associated cancer. Cancer Cell. 2009;15:103-113. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 85. | Bollrath J, Phesse TJ, von Burstin VA, Putoczki T, Bennecke M, Bateman T, Nebelsiek T, Lundgren-May T, Canli O, Schwitalla S. gp130-mediated Stat3 activation in enterocytes regulates cell survival and cell-cycle progression during colitis-associated tumorigenesis. Cancer Cell. 2009;15:91-102. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 86. | Atreya R, Neurath MF. Signaling molecules: the pathogenic role of the IL-6/STAT-3 trans signaling pathway in intestinal inflammation and in colonic cancer. Curr Drug Targets. 2008;9:369-374. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 87. | Atreya R, Neurath MF. Involvement of IL-6 in the pathogenesis of inflammatory bowel disease and colon cancer. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 2005;28:187-196. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 88. | Han X, Sosnowska D, Bonkowski EL, Denson LA. Growth hormone inhibits signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 activation and reduces disease activity in murine colitis. Gastroenterology. 2005;129:185-203. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 89. | Bucolo C, Musumeci M, Maltese A, Drago F, Musumeci S. Effect of chitinase inhibitors on endotoxin-induced uveitis (EIU) in rabbits. Pharmacol Res. 2008;57:247-252. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 90. | Rao FV, Andersen OA, Vora KA, Demartino JA, van Aalten DM. Methylxanthine drugs are chitinase inhibitors: investigation of inhibition and binding modes. Chem Biol. 2005;12:973-980. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 91. | Kronborg G, Ostergaard C, Weis N, Nielsen H, Obel N, Pedersen SS, Price PA, Johansen JS. Serum level of YKL-40 is elevated in patients with Streptococcus pneumoniae bacteremia and is associated with the outcome of the disease. Scand J Infect Dis. 2002;34:323-326. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 92. | Nordenbaek C, Johansen JS, Junker P, Borregaard N, Sørensen O, Price PA. YKL-40, a matrix protein of specific granules in neutrophils, is elevated in serum of patients with community-acquired pneumonia requiring hospitalization. J Infect Dis. 1999;180:1722-1726. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 93. | Létuvé S, Kozhich A, Arouche N, Grandsaigne M, Reed J, Dombret MC, Kiener PA, Aubier M, Coyle AJ, Pretolani M. YKL-40 is elevated in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and activates alveolar macrophages. J Immunol. 2008;181:5167-5173. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 94. | Sanders NN, Eijsink VG, van den Pangaart PS, Joost van Neerven RJ, Simons PJ, De Smedt SC, Demeester J. Mucolytic activity of bacterial and human chitinases. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2007;1770:839-846. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 95. | Ramanathan M Jr, Lee WK, Lane AP. Increased expression of acidic mammalian chitinase in chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyps. Am J Rhinol. 2006;20:330-335. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 96. | Tercelj M, Salobir B, Simcic S, Wraber B, Zupancic M, Rylander R. Chitotriosidase activity in sarcoidosis and some other pulmonary diseases. Scand J Clin Lab Invest. 2009;69:575-578. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 97. | Brunner J, Scholl-Bürgi S, Prelog M, Zimmerhackl LB. Chitotriosidase as a marker of disease activity in sarcoidosis. Rheumatol Int. 2007;27:1185-1186. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 98. | Coffman FD. Chitinase 3-Like-1 (CHI3L1): a putative disease marker at the interface of proteomics and glycomics. Crit Rev Clin Lab Sci. 2008;45:531-562. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 99. | Østergaard C, Johansen JS, Benfield T, Price PA, Lundgren JD. YKL-40 is elevated in cerebrospinal fluid from patients with purulent meningitis. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol. 2002;9:598-604. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 100. | Bonneh-Barkay D, Bissel SJ, Wang G, Fish KN, Nicholl GC, Darko SW, Medina-Flores R, Murphey-Corb M, Rajakumar PA, Nyaundi J. YKL-40, a marker of simian immunodeficiency virus encephalitis, modulates the biological activity of basic fibroblast growth factor. Am J Pathol. 2008;173:130-143. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 101. | Pozzuoli A, Valvason C, Bernardi D, Plebani M, Fabris Monterumici D, Candiotto S, Aldegheri R, Punzi L. YKL-40 in human lumbar herniated disc and its relationships with nitric oxide and cyclooxygenase-2. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2007;25:453-456. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 102. | Brunner JK, Scholl-Bürgi S, Hössinger D, Wondrak P, Prelog M, Zimmerhackl LB. Chitotriosidase activity in juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Rheumatol Int. 2008;28:949-950. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 103. | Johansen JS, Hvolris J, Hansen M, Backer V, Lorenzen I, Price PA. Serum YKL-40 levels in healthy children and adults. Comparison with serum and synovial fluid levels of YKL-40 in patients with osteoarthritis or trauma of the knee joint. Br J Rheumatol. 1996;35:553-559. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 104. | Huang K, Wu LD. YKL-40: a potential biomarker for osteoarthritis. J Int Med Res. 2009;37:18-24. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 105. | Cook EB. Tear cytokines in acute and chronic ocular allergic inflammation. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol. 2004;4:441-445. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 106. | Musumeci M, Bellin M, Maltese A, Aragona P, Bucolo C, Musumeci S. Chitinase levels in the tears of subjects with ocular allergies. Cornea. 2008;27:168-173. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 107. | Takaishi S, Wang TC. Gene expression profiling in a mouse model of Helicobacter-induced gastric cancer. Cancer Sci. 2007;98:284-293. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 108. | Cozzarini E, Bellin M, Norberto L, Polese L, Musumeci S, Lanfranchi G, Paoletti MG. CHIT1 and AMCase expression in human gastric mucosa: correlation with inflammation and Helicobacter pylori infection. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;21:1119-1126. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 109. | Koutroubakis IE, Petinaki E, Dimoulios P, Vardas E, Roussomoustakaki M, Maniatis AN, Kouroumalis EA. Increased serum levels of YKL-40 in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2003;18:254-259. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 110. | Nøjgaard C, Høst NB, Christensen IJ, Poulsen SH, Egstrup K, Price PA, Johansen JS. Serum levels of YKL-40 increases in patients with acute myocardial infarction. Coron Artery Dis. 2008;19:257-263. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 111. | Wang Y, Ripa RS, Johansen JS, Gabrielsen A, Steinbruchel DA, Friis T, Bindslev L, Haack-Sørensen M, Jørgensen E, Kastrup J. YKL-40 a new biomarker in patients with acute coronary syndrome or stable coronary artery disease. Scand Cardiovasc J. 2008;42:295-302. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 112. | Troidl C, Möllmann H, Nef H, Masseli F, Voss S, Szardien S, Willmer M, Rolf A, Rixe J, Troidl K. Classically and alternatively activated macrophages contribute to tissue remodelling after myocardial infarction. J Cell Mol Med. 2009;42:Epub ahead of print. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 113. | Boot RG, van Achterberg TA, van Aken BE, Renkema GH, Jacobs MJ, Aerts JM, de Vries CJ. Strong induction of members of the chitinase family of proteins in atherosclerosis: chitotriosidase and human cartilage gp-39 expressed in lesion macrophages. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 1999;19:687-694. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 114. | Shackel NA, McGuinness PH, Abbott CA, Gorrell MD, McCaughan GW. Novel differential gene expression in human cirrhosis detected by suppression subtractive hybridization. Hepatology. 2003;38:577-588. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 115. | Berres ML, Papen S, Pauels K, Schmitz P, Zaldivar MM, Hellerbrand C, Mueller T, Berg T, Weiskirchen R, Trautwein C. A functional variation in CHI3L1 is associated with severity of liver fibrosis and YKL-40 serum levels in chronic hepatitis C infection. J Hepatol. 2009;50:370-376. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 116. | Malaguarnera L, Rosa MD, Zambito AM, dell'Ombra N, Marco RD, Malaguarnera M. Potential role of chitotriosidase gene in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease evolution. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:2060-2069. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 117. | Malaguarnera L, Di Rosa M, Zambito AM, dell'Ombra N, Nicoletti F, Malaguarnera M. Chitotriosidase gene expression in Kupffer cells from patients with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Gut. 2006;55:1313-1320. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 118. | Johansen JS, Christoffersen P, Møller S, Price PA, Henriksen JH, Garbarsch C, Bendtsen F. Serum YKL-40 is increased in patients with hepatic fibrosis. J Hepatol. 2000;32:911-920. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 119. | Van Steijn GJ, Amerongen AV, Veerman EC, Kasanmoentalib S, Overdijk B. Effect of periodontal treatment on the activity of chitinase in whole saliva of periodontitis patients. J Periodontal Res. 2002;37:245-249. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 120. | Van Steijn GJ, Amerongen AV, Veerman EC, Kasanmoentalib S, Overdijk B. Chitinase in whole and glandular human salivas and in whole saliva of patients with periodontal inflammation. Eur J Oral Sci. 1999;107:328-337. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 121. | Nordenbaek C, Johansen JS, Halberg P, Wiik A, Garbarsch C, Ullman S, Price PA, Jacobsen S. High serum levels of YKL-40 in patients with systemic sclerosis are associated with pulmonary involvement. Scand J Rheumatol. 2005;34:293-297. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 122. | La Montagna G, D'Angelo S, Valentini G. Cross-sectional evaluation of YKL-40 serum concentrations in patients with systemic sclerosis. Relationship with clinical and serological aspects of disease. J Rheumatol. 2003;30:2147-2151. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 123. | Lal A, Lash AE, Altschul SF, Velculescu V, Zhang L, McLendon RE, Marra MA, Prange C, Morin PJ, Polyak K. A public database for gene expression in human cancers. Cancer Res. 1999;59:5403-5407. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 124. | Markert JM, Parker JN, Gillespie GY, Whitley RJ. Genetically engineered human herpes simplex virus in the treatment of brain tumours. Herpes. 2001;8:17-22. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 125. | Tanwar MK, Gilbert MR, Holland EC. Gene expression microarray analysis reveals YKL-40 to be a potential serum marker for malignant character in human glioma. Cancer Res. 2002;62:4364-4368. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 126. | Nutt CL, Betensky RA, Brower MA, Batchelor TT, Louis DN, Stemmer-Rachamimov AO. YKL-40 is a differential diagnostic marker for histologic subtypes of high-grade gliomas. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11:2258-2264. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 127. | Pelloski CE, Mahajan A, Maor M, Chang EL, Woo S, Gilbert M, Colman H, Yang H, Ledoux A, Blair H. YKL-40 expression is associated with poorer response to radiation and shorter overall survival in glioblastoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11:3326-3334. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 128. | Pelloski CE, Ballman KV, Furth AF, Zhang L, Lin E, Sulman EP, Bhat K, McDonald JM, Yung WK, Colman H. Epidermal growth factor receptor variant III status defines clinically distinct subtypes of glioblastoma. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:2288-2294. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 129. | Hormigo A, Gu B, Karimi S, Riedel E, Panageas KS, Edgar MA, Tanwar MK, Rao JS, Fleisher M, DeAngelis LM. YKL-40 and matrix metalloproteinase-9 as potential serum biomarkers for patients with high-grade gliomas. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12:5698-5704. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 130. | Rousseau A, Nutt CL, Betensky RA, Iafrate AJ, Han M, Ligon KL, Rowitch DH, Louis DN. Expression of oligodendroglial and astrocytic lineage markers in diffuse gliomas: use of YKL-40, ApoE, ASCL1, and NKX2-2. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2006;65:1149-1156. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 131. | Saidi A, Javerzat S, Bellahcène A, De Vos J, Bello L, Castronovo V, Deprez M, Loiseau H, Bikfalvi A, Hagedorn M. Experimental anti-angiogenesis causes upregulation of genes associated with poor survival in glioblastoma. Int J Cancer. 2008;122:2187-2198. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 132. | Bhat KP, Pelloski CE, Zhang Y, Kim SH, deLaCruz C, Rehli M, Aldape KD. Selective repression of YKL-40 by NF-kappaB in glioma cell lines involves recruitment of histone deacetylase-1 and -2. FEBS Lett. 2008;582:3193-3200. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 133. | Johansen JS, Lottenburger T, Nielsen HJ, Jensen JE, Svendsen MN, Kollerup G, Christensen IJ. Diurnal, weekly, and long-time variation in serum concentrations of YKL-40 in healthy subjects. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2008;17:2603-2608. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 134. | Junker N, Johansen JS, Andersen CB, Kristjansen PE. Expression of YKL-40 by peritumoral macrophages in human small cell lung cancer. Lung Cancer. 2005;48:223-231. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 135. | Johansen JS, Jensen BV, Roslind A, Nielsen D, Price PA. Serum YKL-40, a new prognostic biomarker in cancer patients? Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2006;15:194-202. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 136. | Cintin C, Johansen JS, Christensen IJ, Price PA, Sørensen S, Nielsen HJ. Serum YKL-40 and colorectal cancer. Br J Cancer. 1999;79:1494-1499. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 137. | Morgante M, Di Munno O, Morgante D. [YKL 40: marker of disease activity in rheumatoid arthritis?]. Minerva Med. 1999;90:437-441. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 138. | Høgdall EV, Kjaer SK, Glud E, Christensen L, Blaakaer J, Vuust J, Bock JE, Norgaard-Pedersen B, Hogdall CK. Evaluation of a polymorphism in intron 2 of the p53 gene in ovarian cancer patients. From the Danish "Malova" Ovarian Cancer Study. Anticancer Res. 2003;23:3397-3404. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 139. | Dupont J, Tanwar MK, Thaler HT, Fleisher M, Kauff N, Hensley ML, Sabbatini P, Anderson S, Aghajanian C, Holland EC. Early detection and prognosis of ovarian cancer using serum YKL-40. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:3330-3339. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 140. | Svane IM, Pedersen AE, Johansen JS, Johnsen HE, Nielsen D, Kamby C, Ottesen S, Balslev E, Gaarsdal E, Nikolajsen K. Vaccination with p53 peptide-pulsed dendritic cells is associated with disease stabilization in patients with p53 expressing advanced breast cancer; monitoring of serum YKL-40 and IL-6 as response biomarkers. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2007;56:1485-1499. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 141. | Yamac D, Ozturk B, Coskun U, Tekin E, Sancak B, Yildiz R, Atalay C. Serum YKL-40 levels as a prognostic factor in patients with locally advanced breast cancer. Adv Ther. 2008;25:801-809. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 142. | Berntsen A, Trepiakas R, Wenandy L, Geertsen PF, thor Straten P, Andersen MH, Pedersen AE, Claesson MH, Lorentzen T, Johansen JS. Therapeutic dendritic cell vaccination of patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma: a clinical phase 1/2 trial. J Immunother. 2008;31:771-780. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 143. | Lau SH, Sham JS, Xie D, Tzang CH, Tang D, Ma N, Hu L, Wang Y, Wen JM, Xiao G. Clusterin plays an important role in hepatocellular carcinoma metastasis. Oncogene. 2006;25:1242-1250. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 144. | Kucur M, Isman FK, Balci C, Onal B, Hacibekiroglu M, Ozkan F, Ozkan A. Serum YKL-40 levels and chitotriosidase activity as potential biomarkers in primary prostate cancer and benign prostatic hyperplasia. Urol Oncol. 2008;26:47-52. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 145. | Huang Y, Prasad M, Lemon WJ, Hampel H, Wright FA, Kornacker K, LiVolsi V, Frankel W, Kloos RT, Eng C. Gene expression in papillary thyroid carcinoma reveals highly consistent profiles. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:15044-15049. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 146. | Sjögren H, Meis-Kindblom JM, Orndal C, Bergh P, Ptaszynski K, Aman P, Kindblom LG, Stenman G. Studies on the molecular pathogenesis of extraskeletal myxoid chondrosarcoma-cytogenetic, molecular genetic, and cDNA microarray analyses. Am J Pathol. 2003;162:781-792. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 147. | Mylin AK, Rasmussen T, Johansen JS, Knudsen LM, Nørgaard PH, Lenhoff S, Dahl IM, Johnsen HE. Serum YKL-40 concentrations in newly diagnosed multiple myeloma patients and YKL-40 expression in malignant plasma cells. Eur J Haematol. 2006;77:416-424. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 148. | Mylin AK, Andersen NF, Johansen JS, Abildgaard N, Heickendorff L, Standal T, Gimsing P, Knudsen LM. Serum YKL-40 and bone marrow angiogenesis in multiple myeloma. Int J Cancer. 2009;124:1492-1494. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 149. | Balamurugan A, Ahmed F, Saraiya M, Kosary C, Schwenn M, Cokkinides V, Flowers L, Pollack LA. Potential role of human papillomavirus in the development of subsequent primary in situ and invasive cancers among cervical cancer survivors. Cancer. 2008;113:2919-2925. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 150. | Cuzick J, Arbyn M, Sankaranarayanan R, Tsu V, Ronco G, Mayrand MH, Dillner J, Meijer CJ. Overview of human papillomavirus-based and other novel options for cervical cancer screening in developed and developing countries. Vaccine. 2008;26 Suppl 10:K29-K41. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 151. | Hasan UA, Bates E, Takeshita F, Biliato A, Accardi R, Bouvard V, Mansour M, Vincent I, Gissmann L, Iftner T. TLR9 expression and function is abolished by the cervical cancer-associated human papillomavirus type 16. J Immunol. 2007;178:3186-3197. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 152. | Mitchell H, Drake M, Medley G. Prospective evaluation of risk of cervical cancer after cytological evidence of human papilloma virus infection. Lancet. 1986;1:573-575. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 153. | Ekbom A, Helmick C, Zack M, Adami HO. Ulcerative colitis and colorectal cancer. A population-based study. N Engl J Med. 1990;323:1228-1233. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 154. | Greenstein AJ, Sachar DB, Smith H, Pucillo A, Papatestas AE, Kreel I, Geller SA, Janowitz HD, Aufses AH Jr. Cancer in universal and left-sided ulcerative colitis: factors determining risk. Gastroenterology. 1979;77:290-294. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 155. | Itzkowitz SH, Yio X. Inflammation and cancer IV. Colorectal cancer in inflammatory bowel disease: the role of inflammation. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2004;287:G7-G17. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 156. | Sugita A, Sachar DB, Bodian C, Ribeiro MB, Aufses AH Jr, Greenstein AJ. Colorectal cancer in ulcerative colitis. Influence of anatomical extent and age at onset on colitis-cancer interval. Gut. 1991;32:167-169. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 157. | Branco BC, Harpaz N, Sachar DB, Greenstein AJ, Tabrizian P, Bauer JJ, Greenstein AJ. Colorectal carcinoma in indeterminate colitis. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2009;15:1076-1081. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 158. | Gyde SN, Prior P, Macartney JC, Thompson H, Waterhouse JA, Allan RN. Malignancy in Crohn's disease. Gut. 1980;21:1024-1029. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 159. | Sachar DB. Cancer in Crohn's disease: dispelling the myths. Gut. 1994;35:1507-1508. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 160. | Nagata E, Sakai K, Kinoshita H, Kobayashi Y. The relation between carcinoma of the gallbladder and an anomalous connection between the choledochus and the pancreatic duct. Ann Surg. 1985;202:182-190. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 161. | Yanagisawa N, Mikami T, Koike M, Okayasu I. Enhanced cell kinetics, p53 accumulation and high p21WAF1 expression in chronic cholecystitis: comparison with background mucosa of gallbladder carcinomas. Histopathology. 2000;36:54-61. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 162. | Zhang M, Pan JW, Ren TR, Zhu YF, Han YJ, Kühnel W. Correlated expression of inducible nitric oxide synthase and P53, Bax in benign and malignant diseased gallbladder. Ann Anat. 2003;185:549-554. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 163. | El-Serag HB, Davila JA, Petersen NJ, McGlynn KA. The continuing increase in the incidence of hepatocellular carcinoma in the United States: an update. Ann Intern Med. 2003;139:817-823. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 164. | Ezzikouri S, El Feydi AE, Chafik A, Afifi R, El Kihal L, Benazzouz M, Hassar M, Pineau P, Benjelloun S. Genetic polymorphism in the manganese superoxide dismutase gene is associated with an increased risk for hepatocellular carcinoma in HCV-infected Moroccan patients. Mutat Res. 2008;649:1-6. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 165. | Huo TI, Huang YH, Hsia CY, Su CW, Lin HC, Hsu CY, Lee PC, Lui WY, Loong CC, Chiang JH. Characteristics and outcome of patients with dual hepatitis B and C-associated hepatocellular carcinoma: are they different from patients with single virus infection? Liver Int. 2009;29:767-773. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 166. | Schmitz KJ, Wohlschlaeger J, Lang H, Sotiropoulos GC, Malago M, Steveling K, Reis H, Cicinnati VR, Schmid KW, Baba HA. Activation of the ERK and AKT signalling pathway predicts poor prognosis in hepatocellular carcinoma and ERK activation in cancer tissue is associated with hepatitis C virus infection. J Hepatol. 2008;48:83-90. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 167. | Wu CF, Yu MW, Lin CL, Liu CJ, Shih WL, Tsai KS, Chen CJ. Long-term tracking of hepatitis B viral load and the relationship with risk for hepatocellular carcinoma in men. Carcinogenesis. 2008;29:106-112. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 168. | Ardies CM. Inflammation as cause for scar cancers of the lung. Integr Cancer Ther. 2003;2:238-246. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 169. | Ballaz S, Mulshine JL. The potential contributions of chronic inflammation to lung carcinogenesis. Clin Lung Cancer. 2003;5:46-62. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 170. | Engels EA. Inflammation in the development of lung cancer: epidemiological evidence. Expert Rev Anticancer Ther. 2008;8:605-615. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 171. | Ke Q, Li J, Ding J, Ding M, Wang L, Liu B, Costa M, Huang C. Essential role of ROS-mediated NFAT activation in TNF-alpha induction by crystalline silica exposure. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2006;291:L257-L264. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 172. | Moghaddam SJ, Li H, Cho SN, Dishop MK, Wistuba II, Ji L, Kurie JM, Dickey BF, Demayo FJ. Promotion of lung carcinogenesis by chronic obstructive pulmonary disease-like airway inflammation in a K-ras-induced mouse model. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2009;40:443-453. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 173. | Walser T, Cui X, Yanagawa J, Lee JM, Heinrich E, Lee G, Sharma S, Dubinett SM. Smoking and lung cancer: the role of inflammation. Proc Am Thorac Soc. 2008;5:811-815. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 174. | Yamasaki A, Tomita K, Chikumi H, Tatsukawa T, Shigeoka Y, Nakamoto M, Hashimoto K, Hasegawa Y, Shimizu E. Lung cancer arising in association with middle lobe syndrome. Anticancer Res. 2006;26:2213-2216. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 175. | Merritt MA, Green AC, Nagle CM, Webb PM. Talcum powder, chronic pelvic inflammation and NSAIDs in relation to risk of epithelial ovarian cancer. Int J Cancer. 2008;122:170-176. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 176. | Ness RB, Goodman MT, Shen C, Brunham RC. Serologic evidence of past infection with Chlamydia trachomatis, in relation to ovarian cancer. J Infect Dis. 2003;187:1147-1152. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 177. | Risch HA, Howe GR. Pelvic inflammatory disease and the risk of epithelial ovarian cancer. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 1995;4:447-451. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 178. | Algül H, Treiber M, Lesina M, Schmid RM. Mechanisms of disease: chronic inflammation and cancer in the pancreas--a potential role for pancreatic stellate cells? Nat Clin Pract Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;4:454-462. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 179. | Bansal P, Sonnenberg A. Pancreatitis is a risk factor for pancreatic cancer. Gastroenterology. 1995;109:247-251. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 180. | Malka D, Hammel P, Maire F, Rufat P, Madeira I, Pessione F, Lévy P, Ruszniewski P. Risk of pancreatic adenocarcinoma in chronic pancreatitis. Gut. 2002;51:849-852. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 181. | Rebours V, Boutron-Ruault MC, Schnee M, Férec C, Le Maréchal C, Hentic O, Maire F, Hammel P, Ruszniewski P, Lévy P. The natural history of hereditary pancreatitis: a national series. Gut. 2009;58:97-103. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 182. | Whitcomb DC. Inflammation and Cancer V. Chronic pancreatitis and pancreatic cancer. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2004;287:G315-G319. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 183. | Zhang Q, Meng Y, Zhang L, Chen J, Zhu D. RNF13: a novel RING-type ubiquitin ligase over-expressed in pancreatic cancer. Cell Res. 2009;19:348-357. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 184. | Tu S, Bhagat G, Cui G, Takaishi S, Kurt-Jones EA, Rickman B, Betz KS, Penz-Oesterreicher M, Bjorkdahl O, Fox JG. Overexpression of interleukin-1beta induces gastric inflammation and cancer and mobilizes myeloid-derived suppressor cells in mice. Cancer Cell. 2008;14:408-419. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 185. | Takaishi S, Okumura T, Wang TC. Gastric cancer stem cells. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:2876-2882. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 186. | Swisher SC, Barbati AJ. Helicobacter pylori strikes again: gastric mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) lymphoma. Gastroenterol Nurs. 2007;30:348-354; quiz 355-356. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 187. | Coskun U, Günel N, Eroglu A, Biri H, Poyraz A, Gurocak S, Musa Bali MD. Primary high grade malignant lymphoma of bladder. Urol Oncol. 2002;7:181-183. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 188. | El-Bolkainy MN, Mokhtar NM, Ghoneim MA, Hussein MH. The impact of schistosomiasis on the pathology of bladder carcinoma. Cancer. 1981;48:2643-2648. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 189. | Mostafa MH, Sheweita SA, O'Connor PJ. Relationship between schistosomiasis and bladder cancer. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1999;12:97-111. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 190. | Rosin MP, Anwar WA, Ward AJ. Inflammation, chromosomal instability, and cancer: the schistosomiasis model. Cancer Res. 1994;54:1929s-1933s. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 191. | Broomé U, Löfberg R, Veress B, Eriksson LS. Primary sclerosing cholangitis and ulcerative colitis: evidence for increased neoplastic potential. Hepatology. 1995;22:1404-1408. [Cited in This Article: ] |