Published online May 21, 2005. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v11.i19.2953

Revised: July 13, 2004

Accepted: August 31, 2004

Published online: May 21, 2005

AIM: To assess the computed tomography (CT) findings in the patients with hepatic portal venous gas (HPVG) who presented with a short fatal clinical course in our hospital in order to demonstrate if there was any sign for prediction.

METHODS: Between January 1997 and December 2000, CT scan of the abdomen was performed on 949 patients with acute abdominal pain in our emergency department. Five patients were found having HPVG. The CT images and clinical presentations of all these five patients were reviewed.

RESULTS: In reviewing the CT findings of the cases, HPVG in bilateral hepatic lobes, abnormal gas in the superior mesenteric veins, small bowel intramural gas, and bowel distension were observed in all patients. Dry gas in multiple branches of the mesenteric vein was also revealed in all cases. All the patients expired due to irreversible septic shock within 48 h after their initial clinical presentation in emergency room. Two patients had acute pancreatitis with grade D and E Balthazar classification and they expired within 24 h due to progressing septic shock under aggressive medical treatment and life support. Two patients with underlying end stage renal disease expired within 48 h even though emergent surgical intervention was undertaken. The excited bowels revealed severe ischemic change. One patient expired only a few hours after the CT examination.

CONCLUSION: HPVG is a diagnostic clue in patients with acute abdominal conditions, and CT is the most specific diagnostic tool for its evaluation. The dry mesenteric veins are the suggestive fatal sign, especially for the deteriorating patients, with the direct effect on gastrointestinal perfusion.

- Citation: Chan SC, Wan YL, Cheung YC, Ng SH, Wong AMC, Ng KK. Computed tomography findings in fatal cases of enormous hepatic portal venous gas. World J Gastroenterol 2005; 11(19): 2953-2955

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v11/i19/2953.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v11.i19.2953

Hepatic portal vein gas (HPVG) is an uncommon feature of acute abdomen. Its radiological findings were first described in children with necrotizing enteritis in 1955[1] followed by the first publication of HPVG in an adult in 1960[2]. HPVG was associated with necrotic bowel (72%), ulcerative colitis (8%), intra-abdominal abscess (6%), small bowel obstruction (3%), and gastric ulcer (3%)[3]. Recognition of HPVG in acute abdomen is important because of high mortality despite intense, conservative medical treatment or urgent surgery[3]. The clinical outcomes of the acute abdomen with HPVG vary.

Radiological signs of abnormal air density in the hepatic region, either with or without gastrointestinal disturbance, are diagnostic clues for such urgent conditions. HPVG can be identified on plain radiography, computed tomography (CT) and ultrasound. Among these imaging modalities, CT is the most sensitive and specific for detecting HPVG and for demonstrating associated intra-abdominal disorders and coexisting abnormal air. Features of pneumatosis intestinalis are most frequently observed, accounting of 50-75% of cases[4]. Demonstration of associated intra-abdominal conditions is essential for planning treatment. On the other hand, prediction of fatalities helps to avoid ineffective aggressive procedures. We reviewed five fatal cases of enormous HPVG. These patients died within 2 d after initial presentation at the emergency room, despite intense medical treatment. We reviewed these cases in order to better understand the clinical course and CT findings of HPVG.

We searched the hospital records for emergency abdomino-pelvic CT studies from January 1997 to December 2000 and found 949 patients with acute abdomen. CT was performed using a helical CT scanner (HiSpeed CT/I; GE Medical Systems, Milwaukee, WI, USA). All examinations were standardized with an axial section thickness of 10 mm from the liver dome to the pelvic floor after oral intake of 600 mL of 4% iothalamate meglumine (Conray 60, Mallinck-rodt Canada Incorporated, Quebec, Canada). The enhancement technique and scanning time were the same for all patients, with the total dosage of 100 mL 60% iothalamate meglumine (Conray 60, Mallinckrodt Canada Incorporated, Quebec, Canada) at a 2 mL/s injection rate. All images were reviewed by two radiologists (Chan SC, Cheung YC) to identify cases of HPVG and to determine the associated CT findings, including coexisting abnormal air and intra-abdominal conditions. Medical records were reviewed to determine clinical courses and outcomes.

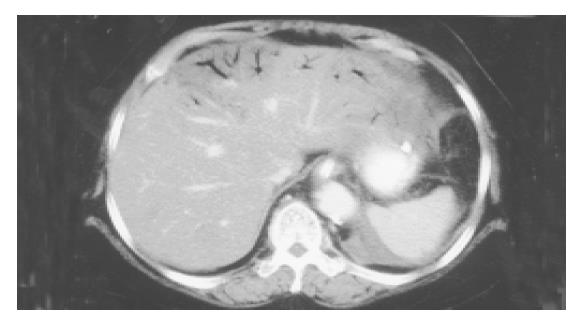

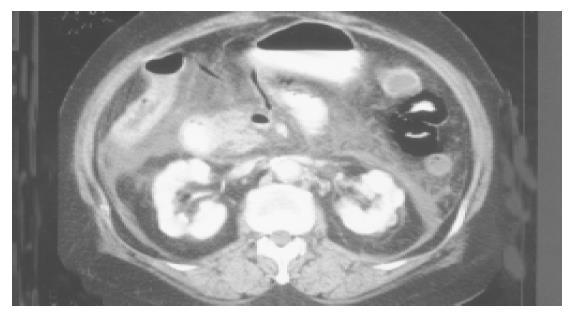

Five patients (two men and three women) with ages ranging from 50 to 90 years were found having HPVG. All five patients complained of an acute abdomen at their initial presentation in our emergency room. They all presented with severe abdominal pain and leukocytosis. Of them, two patients had elevated serum amylase (646 and 213 U/L, respectively) levels that were suggestive of acute pancreatitis. These five patients also had chronic diseases such as hypertension, alcoholism and diabetes mellitus (Table 1). Upon emergency CT, HPVG in bilateral hepatic lobes (Figure 1), abnormal gas in the superior mesenteric veins, small bowel intramural gas, and bowel distension were observed in all cases. Additionally, multiple branches of the mesenteric vein that appeared with dry gas were visualized in all patients (Figure 2). Of them, colonic intramural gas was also visible in two patients. One patient had pneumoperitoneum.

| Patient | Age (yr) | Sex | HPVG | SMVgas | Intram ural gas | Metabolicacidosis | Bowel distention | Clinical manifestations | Underlying disease | Prognosis | |

| Small bowel | Colon | ||||||||||

| 1 | 90 | M | + | + | + | - | - | + | Segmental small bowel ischemia | Chronic renal insufficiency, hypertension | Expired within 72 h after operation |

| 2 | 71 | F | + | + | + | - | + | + | Acute pancreatitis | Hypertension, DM | Expired within 24 h |

| 3 | 72 | F | + | + | + | - | + | + | Rapid progressionof septic shock | Ischemia heart disease, gouty arthritis | Expired within 24 h |

| 4 | 50 | M | + | + | + | + | + | + | Acute pancreatitis | Alcoholism, DM | Expired within 24 h |

| 5 | 65 | F | + | + | + | + | - | + | Long segmental small bowel ischemia | ESRD, DM, hypertension | Expired within 12 h after operation |

Two patients underwent emergency exploratory laparotomy after CT examination. The 65-year-old female patient had end-stage renal disease and under regular hemodialysis was found to have extensive ischemic bowel disease from the Treitz ligament to the ileocecal value, with more than 1000 mL of turbid ascites fluid. Only surgical open and close was done. She expired within 12 h due to irreversible septic shock. Another case of a 90-year-old male patient had the chronic renal insufficiency and after surgery, 40 cm of small bowel gangrene was found. The necrotic bowel was resected, but his clinical condition worsened because of infection and multiple organ failure; he expired within 48 h after surgery due to irreversible septic shock. The two patients with suspected pancreatitis had Balthazar classifications D and E disease, respectively, on CT imaging. Even though these four patients were given intense medical treatment with antibiotics and life support, they expired within 24 h after initial clinical presentation due to rapidly progressing septic shock. The remaining patient expired a few hours after CT due to irreversible septic shock.

The pathogenesis of HPVG is not fully understood. Two theories, mechanical and bacterial, have been proposed. The mechanical theory proposes that gas dissects into the bowel wall from either the intestinal lumen or the lung[5]. Mucosal damage and bowel distention are important factors in this theory. Mucosal damage allows intraluminal gas to enter the venous system. About 85% of patients with HPVG have mucosal ulceration with bowel distention and increased intramural pressure[5]. The bacterial theory proposes that gas-forming bacilli enter the submucosa through mucosal rents and produce gas within the intestinal wall and then enter into the portal vein[5].

In cases of ischemic bowel distention with mucosal damage, mucosal damage allows gas to enter the mesenteric vessels directly[6,7]. Bowel distention and ischemia can also produce minimal mucosal disruption that allows intraluminal gas to become intravascular[8]. To our knowledge, HPVG is a rare complication of acute pancreatitis, first reported in 1961[9]. In 1997, Faberman and Mayo-Smith reported three more cases and proposed that HPVG was caused by the breakdown of intestinal mucosa by pancreatic enzymes or mucosal disru-ption that induced intestinal ischemia[10]. They demonstrated that pancreatitis with HPVG may not have as fulminant a course as previously thought. However, two of our patients with apparent pancreatitis died within 24 h after diagnosis. This situation may suggest that the clinical outcome of acute pancreatitis with HPVG is variable.

Long-term chronic diseases decrease the immune function and tolerance capability of the HPVG patients, which might lead to fatality[11]. Among our five patients, one had chronic renal insufficiency and another had end-stage renal disease. In addition, the remaining patients had diabetes mellitus, hypertension, ischemic heart disease, or alcoholism (Table 1). Patients with chronic renal failure have greatly increased numbers of microbial flora, both anaerobes and aerobes, in the small intestine or during hemodialysis. According to their medical records, the patients had been examined and treated for long-term infections. These patients all took long-term medication to control their deteriorating underlying conditions. For this reason, we suppose that the disruption of the small bowel mucosa was related to the effects of long-term medications or to deteriorating health conditions that could have promoted HPVG formation[12].

Evidence-based signs of HPVG are comparatively more important than understanding the mechanism of HPVG formation. The CT features of all five of our patients included bowel distention, gas in the superior mesenteric vein and pneumatosis intestinalis. Nonetheless, the CT findings do not indicate the proposed mechanism of HPVG formation. CT findings of air-fluid levels and dry gas within the mesenteric veins were common signs; however, sign of mesenteric venous dry gas in our cases indicated the subsequent occurrence of gastrointestinal ischemia secondary to the venous air blockage. These signs may prospectively relate to the impending death, if the condition is irreversible.

Regardless of the CT diagnosis of HPVG, CT also provides greater detail of patients’ intra-abdominal conditions. The CT features of superior mesenteric vein gas, bowel distention, pneumatosis intestinalis or pneumoperitoneum were commonly found. Signs of dry gas in multiple branches of the mesenteric veins may suggest a fatal course inducing with progressing bowel ischemia, especially among patients with deteriorating chronic systemic diseases in our cases.

Science Editor Li WZ Language Editor Elsevier HK

| 1. | Wolfe JN, Evans WA. Gas in the portal veins of the liver in infants; a roentgenographic demonstration with postmortem anatomical correlation. Am J Roentgenol Radium Ther Nucl Med. 1955;74:486-488. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 2. | Susman N, Senturia HR. Gas embolization of the portal venous system. Am J Roentgenol Radium Ther Nucl Med. 1960;83:847-850. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 3. | Liebman PR, Patten MT, Manny J, Benfield JR, Hechtman HB. Hepatic--portal venous gas in adults: etiology, pathophysiology and clinical significance. Ann Surg. 1978;187:281-287. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 356] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 296] [Article Influence: 6.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Sebastià C, Quiroga S, Espin E, Boyé R, Alvarez-Castells A, Armengol M. Portomesenteric vein gas: pathologic mechanisms, CT findings, and prognosis. Radiographics. 2000;20:1213-1224; discussion 1224-1226. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 187] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 169] [Article Influence: 7.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Yamamuro M, Ponsky JL. Hepatic portal venous gas: report of a case. Surg Today. 2000;30:647-650. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 15] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Federle MP, Chun G, Jeffrey RB, Rayor R. Computed tomographic findings in bowel infarction. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1984;142:91-95. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 80] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 82] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Smerud MJ, Johnson CD, Stephens DH. Diagnosis of bowel infarction: a comparison of plain films and CT scans in 23 cases. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1990;154:99-103. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 116] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 122] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Gosink BB. Intrahepatic gas: differential diagnosis. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1981;137:763-767. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 48] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 49] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Wiot JF, Felson B. Gas in the portal venous system. Am J Roentgenol Radium Ther Nucl Med. 1961;86:920-929. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 10. | Faberman RS, Mayo-Smith WW. Outcome of 17 patients with portal venous gas detected by CT. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1997;169:1535-1538. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 119] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 126] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Wolff GT. Hepatic portal venous gas. Am Fam Physician. 1982;26:185-186. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 12. | Morimoto Y, Yamakawa T, Tanaka Y, Hiranaka T, Kim M. Recurrent hepatic portal venous gas in a patient with hemodialysis- dependent chronic renal failure. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg. 2001;8:274-278. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 14] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |