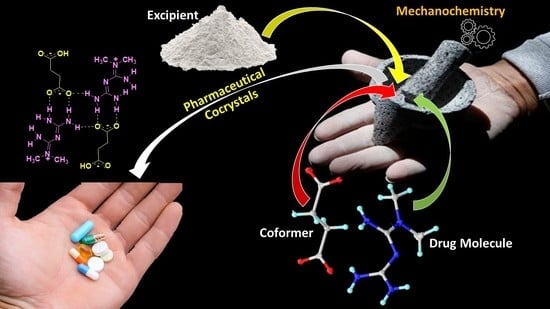

Mechanochemistry: A Green Approach in the Preparation of Pharmaceutical Cocrystals

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Mechanochemistry

2.1. Definitions, Relevant Historical Aspects, and Applications of Mechanochemistry

2.2. Different Mechanochemical Apparatuses

2.3. Advantages of Reaction Performance among Grinding/Milling and Other Sustainable Methods

2.4. Preparative Conditions of Mechanochemical Methods of Pharmaceutical Cocrystals

- Intersolid reactions, which pertain to the reactivity between solids (mechanochemical reactions), Figure 4.

- Reactions between solids (solid–state reactions).

- Reactions between solids with intermediate local melting.

- Reactions with at least one liquid reagent.

2.5. Mechanistic Aspects in Cocrystal Formation Applying Mechanochemistry

- Molecule migration. The first stage is the reconstruction of the solid phase, suggesting directional long-range migrations of molecules, where component A invades the planes or channels of component B (or vice-versa). The incipient formation of C distorts the original crystal structures of A and B, producing a mixed A-B-C phase.

- Product-phase formation. The concomitant appearance of component C in the mixed phase A-B-C favors spatial discontinuity in particles A and B due to strain and crystal defects.

- Crystal disintegration. In this step, is suggested a chemical and geometrical mismatch between components A and B, produced by the appearance of C causing a disintegration of the particles. The grinding/milling process produces fresh surfaces available for further reaction to completion.

3. Cocrystal

3.1. Cocrystal Definition

- “Only compounds constructed from discrete neutral molecular species will be considered cocrystals. Consequently, all solids containing ions, including complex transition-metal ions, are excluded”.

- “Only cocrystals made from reactants that are solids at ambient conditions will be included. Therefore, all hydrates and other solvates are excluded which, in principle, eliminates compounds that are typically classified as clathrates or inclusion compounds (where the guest is a solvent or a gas molecule)”.

- “A cocrystal is a structurally homogeneous crystalline material that contains two or more neutral building blocks that are present in definite stoichiometric amounts”.

3.2. Design of Pharmaceutical Cocrystals: Selection of Appropriate API/Conformer

3.3. Characterization of Pharmaceutical Cocrystals

3.4. Diverse Preparation Methods of Pharmaceutical Cocrystals

3.5. Benefits of Pharmaceutical Cocrystals

3.6. Chronological Survey of Papers Mentioning Mechanochemical Synthesis of Pharmaceutical Cocrystals

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| adi | Adipic acid |

| ana | Anthranilic Acid |

| API | Active Pharmaceutical Ingredient |

| α-alanine | α-ala |

| BA | Barbituric acid |

| BSC | Biopharmaceutics classification system |

| 4,4′-bipy | 4,4′-Bipyridine |

| ca | Citric Acid |

| caf | Caffeine |

| cbz | Carbamazepine |

| CSD | Cambridge structural database |

| CTA | Cyclohexane-1,3-cis-5-cis-tricarboxylic Acid |

| δ | δ parameter |

| dabco | 1,4-diazabicyclo [2.2.2]octane |

| DL-ta | DL-tartaric acid |

| DSC | Differential Scanning Calorimetry |

| DTA | Differential thermal analysis |

| FDA | Food and drug administration |

| FT-IR | Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy |

| GRAS | Generally recognized as safe |

| Glu | Glutaric acid |

| HIMO | 4,5-dimethyl-imidazole-3-oxide |

| IL | Imidazolium based ionic liquids |

| ILAG | Ion liquid-assisted grinding |

| IUPAC | International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry |

| LAG | Liquid-Assisted Grinding |

| LASI | Liquid-assisted sonochemical irradiation |

| ma | Mesaconic Acid |

| MeNO3 | Methyl nitrate |

| MOF | Metal-organic framework |

| m | weights of cocrystal components |

| NP | Natural product |

| NG | Neat Grinding |

| Nicotinamide | nic |

| 5-nip | 5-Nitroisophtalic acid |

| η | η parameter |

| ox | Oxalic Acid |

| PEG | Polyethylene Glycol |

| phe | Phenazide |

| 4,7-phen | 4,7-phenanthroline |

| POLAG | Polymer-Assisted Grinding |

| PMMA | Poly(methyl methacrylate) |

| PXRD | Powder X-ray Diffraction |

| RAM | Resonant acoustic mixing |

| RS-ibp | RS-ibuprofen |

| sa | Salicylic Acid |

| SCXRD | Single Crystal X-ray Diffraction |

| SDG | Solvent Drop Grinding |

| S-ibp | S-ibuprofen |

| ssNMR | solid-state Nuclear Magnetic Resonance |

| ta | Terephthalate |

| thp | Theophillyne |

| TBA | Thiobarbituric acid |

| TGA | Thermogravimetric Analysis |

| TSE | Twin-screw extrusion |

| tp | Theophylline |

| V | volume |

| VALAG | Variable amount liquid-assisted grinding |

| VATEG | Variable temperature grinding |

| XPS | X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy |

References

- Datta, S.; Grant, D.J.W. Crystal Structures of Drugs: Advances in Determination, Prediction and Engineering. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2004, 3, 42–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shekunov, B.Y.; York, P. Crystallization Processes in Pharmaceutical Technology and Drug Delivery Design. J. Cryst. Growth 2000, 211, 122–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grunenberg, A.; Henck, J.O.; Siesler, H.W. Theoretical Derivation and Practical Application of Energy/Temperature Diagrams as an Instrument in Preformulation Studies of Polymorphic Drug Substances. Int. J. Pharm. 1996, 129, 147–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morissette, S.L.; Soukasene, S.; Levinson, D.; Cima, M.J.; Almarsson, O. Elucidation of Crystal Form Diversity of the HIV Protease Inhibitor Ritonavir by High-throughput Crystallization. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2003, 100, 2180–2184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Morissette, S.L.; Almarsson, Ö.; Peterson, M.L.; Remenar, J.F.; Read, M.J.; Lemmo, A.V.; Ellis, S.; Cima, M.J.; Gardner, C.R. High-throughput Crystallization: Polymorphs, Salts, Co-crystals and Solvates of Pharmaceutical Solids. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2004, 56, 275–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiekink, E.R.T.; Vittal, J.; Zaworotko, M. Organic Crystal Engineering: Frontiers in Crystal Engineering; Tiekink, E.R.T., Vittal, J.J., Zaworotko, M.J., Eds.; John Wiley & Sons: New York, NY, USA, 2010; ISBN 9780470319901. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, E.H. A Practical Guide to Pharmaceutical Polymorph Screening & Selection. Asian J. Pharm. Sci. 2014, 9, 163–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Aaltonen, J.; Allesø, M.; Mirza, S.; Koradia, V.; Gordon, K.C.; Rantanen, J. Solid Form Screening—A Review. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. 2009, 71, 23–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tung, H.H. Industrial Perspectives of Pharmaceutical Crystallization. Org. Process Res. Dev. 2013, 17, 445–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Croker, D.M.; Kelly, D.M.; Horgan, D.E.; Hodnett, B.K.; Lawrence, S.E.; Moynihan, H.A.; Rasmuson, Å.C. Demonstrating the Influence of Solvent Choice and Crystallization Conditions on Phenacetin Crystal Habit and Particle Size Distribution. Org. Process Res. Dev. 2015, 19, 1826–1836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keraliya, R.A.; Soni, T.G.; Thakkar, V.T.; Gandhi, T.R. Effect of Solvent on Crystal Habit and Dissolution Behavior of Tolbutamide by Initial Solvent Screening. Dissolution Technol. 2010, 17, 16–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schultheiss, N.; Newman, A. Pharmaceutical Cocrystals and Their Physicochemical Properties. Cryst. Growth Des. 2009, 9, 2950–2967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Berry, D.J.; Steed, J.W. Pharmaceutical Cocrystals, Salts and Multicomponent Systems; Intermolecular Interactions and Property Based Design. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2017, 117, 3–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Karagianni, A.; Malamatari, M.; Kachrimanis, K. Pharmaceutical Cocrystals: New Solid Phase Modification Approaches for the Formulation of APIs. Pharmaceutics 2018, 10, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Healy, A.M.; Worku, Z.A.; Kumar, D.; Madi, A.M. Pharmaceutical Solvates, Hydrates and Amorphous Forms: A Special Emphasis on Cocrystals. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2017, 117, 25–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Myrdal, P.B.; Jozwiakowski, M.J. Alteration of the Solid State of the Drug Substances: Polymorphs, Solvates, and Amorphous Forms. In Water-Insoluble Drug Formulation; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2008; pp. 531–566. [Google Scholar]

- Babu, N.J.; Nangia, A. Solubility Advantage of Amorphous Drugs and Pharmaceutical Cocrystals. Cryst. Growth Des. 2011, 11, 2662–2679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aitipamula, S.; Banerjee, R.; Bansal, A.K.; Biradha, K.; Cheney, M.L.; Choudhury, A.R.; Desiraju, G.R.; Dikundwar, A.G.; Dubey, R.; Duggirala, N.; et al. Polymorphs, Salts, and Cocrystals: What’s in a Name? Cryst. Growth Des. 2012, 12, 2147–2152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalepu, S.; Nekkanti, V. Insoluble Drug Delivery Strategies: Review of Recent Advances and Business Prospects. Acta Pharm. Sin. B 2015, 5, 442–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kavanagh, O.N.; Croker, D.M.; Walker, G.M.; Zaworotko, M.J. Pharmaceutical Cocrystals: From Serendipity to Design to Application. Drug Discov. Today 2019, 24, 796–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bučar, D.-K.; Lancaster, R.W.; Bernstein, J. Disappearing Polymorphs Revisited. Angew. Chem. 2015, 54, 6972–6993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kaushal, A.M.; Gupta, P.; Bansal, A.K. Amorphous Drug Delivery Systems: Molecular Aspects, Design, and Performance. Crit. Rev. Ther. Drug Carrier Syst. 2004, 21, 133–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lipinski, C.A.; Lombardo, F.; Dominy, B.W.; Feeney, P.J. Experimental and Computational Approaches to Estimate Solubility and Permeability in Drug Discovery and Development Settings. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 1997, 23, 3–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lipinski, C.A.; Lombardo, F.; Dominy, B.W.; Feeney, P.J. Experimental and Computational Approaches to Estimate Solubility and Permeability in Drug Discovery and Development Settings. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2012, 64, 4–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rinaki, E.; Valsami, G.; Macheras, P. Quantitative Biopharmaceutics Classification System: The Central Role of Dose/Solubility Ratio. Pharm. Res. 2003, 20, 1917–1925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amidon, G.L.; Lennernäs, H.; Shah, V.P.; Crison, J.R. A Theoretical Basis for a Biopharmaceutic Drug Classification: The Correlation of in Vitro Drug Product Dissolution and in vivo Bioavailability. Pharm. Res. An Off. J. Am. Assoc. Pharm. Sci. 1995, 12, 413–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Amidon, G.L.; Lennernas, H.; Shah, V.P.; Crison, J.R. A Theoretical Basis for a Biopharmaceutic Drug Classification: The Correlation of In Vitro Drug Product Dissolution and In Vivo Bioavailability, Pharm. Res. 12, 413–420, 1995—Backstory of BCS. AAPS J. 2014, 16, 894–898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fujii, S.; Yokoyama, T.; Ikegaya, K.; Sato, F.; Yokoo, N. Promoting Effect of the New Chymotrypsin Inhibitor FK-448 on the Intestinal Absorption of Insulin in Rats and Dogs. J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 1985, 37, 545–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doroshyenko, O.; Jetter, A.; Odenthal, K.P.; Fuhr, U. Clinical Pharmacokinetics of Trospium Chloride. Clin. Pharmacokinet. 2005, 44, 701–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aungst, B.J. Intestinal Permeation Enhancers. J. Pharm. Sci. 2000, 89, 429–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aungst, B.J. Novel Formulation Strategies for Improving Oral Bioavailability of Drugs with Poor Membrane Permeation or Presystemic Metabolism. J. Pharm. Sci. 1993, 82, 979–987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleisher, D.; Bong, R.; Stewart, B.H. Improved Oral Drug Delivery: Solubility Limitations Overcome by the Use of Prodrugs. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 1996, 19, 115–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, K.R.; Fakes, M.G.; Thakur, A.B.; Newman, A.W.; Singh, A.K.; Venit, J.J.; Spagnuolo, C.J.; Serajuddin, A.T.M. An Integrated Approach to the Selection of Optimal Salt Form for a New Drug Candidate. Int. J. Pharm. 1994, 105, 209–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Dai, W.-G. Fundamental Aspects of Solid Dispersion Technology for Poorly Soluble Drugs. Acta Pharm. Sin. B 2014, 4, 18–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Kumar, A. Solid Dispersion- Strategy To Enhance Solubility and Dissolution of Poorly Water Soluble Drugs. Univers. J. Pharm. Res. 2017, 2, 54–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacob, S.; Nair, A.B. Cyclodextrin Complexes: Perspective from Drug Delivery and Formulation. Drug Dev. Res. 2018, 79, 201–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, S.; Date, A.; Holm, R. Strategies for the Formulation Development of Poorly Soluble Drugs via Oral Route. In Innovative Dosage Forms: Design and Development at Early Stage; Bachhav, Y., Ed.; Wiley-VCH Verlag GmbH: Weinheim, Germany, 2019; Chapter 2; pp. 49–89. [Google Scholar]

- Tran, P.H.L.; Tran, T.T.D. Dosage Form Designs for the Controlled Drug Release of Solid Dispersions. Int. J. Pharm. 2020, 581, 119274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jornada, D.H.; dos Santos Fernandes, G.F.; Chiba, D.E.; de Melo, T.R.; dos Santos, J.L.; Chung, M.C. The Prodrug Approach: A Successful Tool for Improving Drug Solubility. Molecules 2016, 21, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Berge, S.M.; Bighley, L.D.; Monkhouse, D.C. Pharmaceutical Salts. J. Pharm. Sci. 1977, 66, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loftsson, T.; Duchêne, D. Cyclodextrins and Their Pharmaceutical Applications. Int. J. Pharm. 2007, 329, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swarnakar, N.K.; Venkatesan, N.; Betageri, G. Critical In Vitro Characterization Methods of Lipid-Based Formulations for Oral Delivery: A Comprehensive Review. AAPS PharmSciTech 2019, 20, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vo, C.L.-N.; Park, C.; Lee, B.-J. Current Trends and Future Perspectives of Solid Dispersions Containing Poorly Water-soluble Drugs. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. 2013, 85, 799–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miroshnyk, I.; Mirza, S.; Sandler, N. Pharmaceutical Co-crystals-An Opportunity for Drug Product Enhancement. Expert Opin. Drug Deliv. 2009, 6, 333–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yousef, M.A.E.; Vangala, V.R. Pharmaceutical Cocrystals: Molecules, Crystals, Formulations, Medicines. Cryst. Growth Des. 2019, 19, 7420–7438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaikh, R.; Singh, R.; Walker, G.M.; Croker, D.M. Pharmaceutical Cocrystal Drug Products: An Outlook on Product Development. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 2018, 39, 1033–1048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thakuria, R.; Delori, A.; Jones, W.; Lipert, M.P.; Roy, L.; Rodríguez-Hornedo, N. Pharmaceutical Cocrystals and Poorly Soluble Drugs. Int. J. Pharm. 2013, 453, 101–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sathisaran, I.; Dalvi, S.V. Engineering Cocrystals of Poorly Water-Soluble Drugs to Enhance Dissolution in Aqueous Medium. Pharmaceutics 2018, 10, 108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Perlovich, G.L.; Manin, A.N. Design of Pharmaceutical Cocrystals for Drug Solubility Improvement. Russ. J. Gen. Chem. 2014, 84, 407–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cherukuvada, S.; Nangia, A. Eutectics as Improved Pharmaceutical Materials: Design, Properties and Characterization. Chem. Commun. 2014, 50, 906–923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoler, E.; Warner, J.C. Non-Covalent Derivatives: Cocrystals and Eutectics. Molecules 2015, 20, 14833–14848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chavan, R.B.; Thipparaboina, R.; Kumar, D.; Shastri, N.R. Co Amorphous Systems: A Product Development Perspective. Int. J. Pharm. 2016, 515, 403–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Q.; Moinuddin, S.M.; Cai, T. Advances in Coamorphous Drug Delivery Systems. Acta Pharm. Sin. B 2019, 9, 19–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarma, B.; Chen, J.; Hsi, H.Y.; Myerson, A.S. Solid Forms of Pharmaceuticals: Polymorphs, Salts and Cocrystals. Korean J. Chem. Eng. 2011, 28, 315–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, C.C. Cocrystallization for Successful Drug Delivery. Expert Opin. Drug Deliv. 2012, 10, 201–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grothe, E.; Meekes, H.; Vlieg, E.; Ter Horst, J.H.; De Gelder, R. Solvates, Salts, and Cocrystals: A Proposal for a Feasible Classification System. Cryst. Growth Des. 2016, 16, 3237–3243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nangia, A.; Bolla, G. Pharmaceutical Cocrystals: Walking the Talk. Chem. Commun. 2016, 52, 8342–8360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duggirala, N.K.; Perry, M.L.; Almarsson, Ö.; Zaworotko, M.J. Pharmaceutical Cocrystals: Along the Path to Improved Medicines. Chem. Commun. 2016, 52, 640–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohamed, S.; Tocher, D.A.; Vickers, M.; Karamertzanis, P.G.; Price, S.L. Salt or Cocrystal? A New Series of Crystal Structures Formed from Simple Pyridines and Carboxylic Acids. Cryst. Growth Des. 2009, 9, 2881–2889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aakeröy, C.B.; Fasulo, M.E.; Desper, J. Cocrystal or Salt: Does It Really Matter? Mol. Pharm. 2007, 4, 317–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Childs, S.L.; Stahly, G.P.; Park, A. The Salt−Cocrystal Continuum: The Influence of Crystal Structure on Ionization Stat. Mol. Pharm. 2007, 4, 323–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Stevens, J.S.; Byard, S.J.; Seaton, C.C.; Sadiq, G.; Davey, R.J.; Schroeder, S.L.M. Proton Transfer and Hydrogen Bonding in the Organic Solid State: A Combined XRD/XPS/ssNMR Study of 17 Organic Acid-base Complexes. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2014, 16, 1150–1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Carolina Bazzo, G.; Ramos Pezzini, B.; Karine Stulzer, H. Eutectic Mixtures as an Approach to Enhance Solubility, Dissolution Rate and Oral Bioavailability of Poorly Water-soluble Drugs. Int. J. Pharm. 2020, 588, 119741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chavan, R.B.; Yadav, B.; Lodagekar, A.; Shastri, N.R. Multicomponent Solid Forms: A New Boost to Pharmaceuticals. In Multifunctional Nanocarriers for Contemporary Healthcare Applications; Barkat, A., Harshita, A.B., Sarwar, B., Farhan, J.A., Eds.; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2018; pp. 273–300. ISBN 9781522547822. [Google Scholar]

- Laitinen, R.; Löbmann, K.; Grohganz, H.; Priemel, P.; Strachan, C.J.; Rades, T. Supersaturating Drug Delivery Systems: The Potential of Co-amorphous Drug Formulations. Int. J. Pharm. 2017, 532, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newman, A.; Zografi, G. An Examination of Water Vapor Sorption by Multicomponent Crystalline and Amorphous Solids and Its Effects on Their Solid-State Properties. J. Pharm. Sci. 2019, 108, 1061–1080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dengale, S.J.; Grohganz, H.; Rades, T.; Löbmann, K. Recent Advances in Co-amorphous Drug Formulations. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2016, 100, 116–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, F.; Scholz, G.; Benemann, S.; Rademann, K.; Emmerling, F. Evaluation of the Formation Pathways of Cocrystal Polymorphs in Liquid-assisted Syntheses. CrystEngComm 2014, 16, 8272–8278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Madusanka, N.; Eddleston, M.D.; Arhangelskis, M.; Jones, W. Polymorphs, Hydrates and Solvates of a Co-crystal of Caffeine with Anthranilic Acid. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. B Struct. Sci. Cryst. Eng. Mater. 2014, 70, 72–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prohens, R.; Barbas, R.; Portell, A.; Font-Bardia, M.; Alcobé, X.; Puigjaner, C. Polymorphism of Cocrystals: The Promiscuous Behavior of Agomelatine. Cryst. Growth Des. 2016, 16, 1063–1070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bevill, M.J.; Vlahova, P.I.; Smit, J.P. Polymorphic Cocrystals of Nutraceutical Compound p-Coumaric Acid with Nicotinamide: Characterization, Relative Solid-State Stability, and Conversion to Alternate Stoichiometries. Cryst. Growth Des. 2014, 14, 1438–1448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eddleston, M.D.; Patel, B.; Day, G.M.; Jones, W. Cocrystallization by Freeze-drying: Preparation of Novel Multicomponent Crystal Forms. Cryst. Growth Des. 2013, 13, 4599–4606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Schultheiss, N.; Roe, M.; Boerrigter, S.X.M. Cocrystals of Nutraceutical P-coumaric Acid with Caffeine and Theophylline: Polymorphism and Solid-state Stability Explored in Detail Using Their Crystal Graphs. CrystEngComm 2011, 13, 611–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mnguni, M.J.; Michael, J.P.; Lemmerer, A. Binary Polymorphic Cocrystals: An Update on the Available Literature in the Cambridge Structural Database, Including a New Polymorph of the Pharmaceutical 1:1 Cocrystal Theophylline–3,4-dihydroxybenzoic Acid. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. C Struct. Chem. 2018, 74, 715–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aitipamula, S.; Chow, P.S.; Tan, R.B.H. Polymorphism in cocrystals: A review and assessment of its significance. CrystEngComm 2014, 16, 3451–3465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Douroumis, D.; Ross, S.A.; Nokhodchi, A. Advanced Methodologies for Cocrystal Synthesis. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2017, 117, 178–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steed, J.W. The Role of Co-crystals in Pharmaceutical Design. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 2013, 34, 185–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Hoang Pham, U.G. Pharmaceutical Applications of Eutectic Mixtures. J. Dev. Drugs 2014, 2, 2–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaupp, G. Mechanochemistry: The Varied Applications of Mechanical Bond-breaking. CrystEngComm 2009, 11, 388–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suslick, K.S. Mechanochemistry and Sonochemistry: Concluding Remarks. Faraday Discuss. 2014, 170, 411–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friščić, T. New Opportunities for Materials Synthesis Using Mechanochemistry. J. Mater. Chem. 2010, 20, 7599–7605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friščić, T.; Mottillo, C.; Titi, H.M. Mechanochemistry for Synthesis. Angew. Chem. 2020, 59, 1018–1029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Achar, T.K.; Bose, A.; Mal, P. Mechanochemical Synthesis of Small Organic Molecules. Beilstein J. Org. Chem. 2017, 13, 1907–1931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Do, J.-L.; Friščić, T. Mechanochemistry: A Force of Synthesis. ACS Cent. Sci. 2017, 3, 13–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bruckmann, A.; Krebs, A.; Bolm, C. Organocatalytic Reactions: Effects of Ball Milling, Microwave and Ultrasound Irradiation. Green Chem. 2008, 10, 1131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pickhardt, W.; Grätz, S.; Borchardt, L. Direct Mechanocatalysis: Using Milling Balls as Catalysts. Chem. Eur. J. 2020, 26, 12903–12911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández, J.G.; Macdonald, N.A.J.; Mottillo, C.; Butler, I.S.; Friščić, T. A Mechanochemical Strategy for Oxidative Addition: Remarkable Yields and Stereoselectivity in the Halogenation of Organometallic Re(I) Complexes. Green Chem. 2014, 16, 1087–1092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chikunov, I.E.; Ranny, G.S.; Astakhov, A.V.; Tafeenko, V.A.; Chernyshev, V.M. Mechanochemical Synthesis of Platinum(IV) Complexes with N-heterocyclic Carbenes. Russ. Chem. Bull. 2018, 67, 2003–2009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, C.J.; Lusi, M.; Mutambi, E.M.; Orpen, A.G. Two-Step Mechanochemical Synthesis of Carbene Complexes of Palladium(II) and Platinum(II). Cryst. Growth Des. 2017, 17, 3151–3155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allenbaugh, R.J.; Zachary, J.R.; Underwood, A.N.; Bryson, J.D.; Williams, J.R.; Shaw, A. Kinetic Analysis of the Complete Mechanochemical Synthesis of a Palladium(II) Carbene Complex. Inorg. Chem. Commun. 2020, 111, 107622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rightmire, N.R.; Hanusa, T.P. Advances in Organometallic Synthesis with Mechanochemical Methods. Dalt. Trans. 2016, 45, 2352–2362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baig, R.B.N.; Varma, R.S. Alternative Energy Input: Mechanochemical, Microwave and Ultrasound-assisted Organic Synthesis. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2012, 41, 1559–1584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersen, J.; Mack, J. Mechanochemistry and Organic Synthesis: From Mystical to Practical. Green Chem. 2018, 20, 1435–1443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leonardi, M.; Villacampa, M.; Menéndez, J.C. Multicomponent Mechanochemical Synthesis. Chem. Sci. 2018, 9, 2042–2064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Stolle, A.; Szuppa, T.; Leonhardt, S.E.S.; Ondruschka, B. Ball Milling in Organic Synthesis: Solutions and Challenges. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2011, 40, 2317–2329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Margetić, D.; Štrukil, V. Practical Considerations. In Mechanochemical Organic Synthesis; Margetić, D., Štrukil, V.B.T.-M.O.S., Eds.; Elsevier: Boston, MA, USA, 2016; Chapter 1; pp. 1–54. ISBN 978-0-12-802184-2. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, G.-W. Mechanochemical Organic Synthesis. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2013, 42, 7668–7700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beillard, A.; Métro, T.X.; Bantreil, X.; Martinez, J.; Lamaty, F. Cu(0), O2 and Mechanical Forces: A Saving Combination for Efficient Production of Cu-NHC Complexes. Chem. Sci. 2017, 8, 1086–1089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Friščić, T.; Halasz, I.; Štrukil, V.; Eckert-Maksić, M.; Dinnebier, R.E. Clean and Efficient Synthesis Using Mechanochemistry: Coordination Polymers, Metal-organic Frameworks and Metallodrugs. Croat. Chem. Acta 2012, 85, 367–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garay, A.L.; Pichon, A.; James, S.L. Solvent-free Synthesis of Metal Complexes. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2007, 36, 846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan, D.; García, F. Main Group Mechanochemistry: From Curiosity to Established Protocols. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2019, 48, 2274–2292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gečiauskaitė, A.A.; García, F. Main Group Mechanochemistry. Beilstein J. Org. Chem. 2017, 13, 2068–2077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chen, D.; Zhao, J.; Zhang, P.; Dai, S. Mechanochemical Synthesis of Metal–organic Frameworks. Polyhedron 2019, 162, 59–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klimakow, M.; Klobes, P.; Thünemann, A.F.; Rademann, K.; Emmerling, F. Mechanochemical Synthesis of Metal-organic Frameworks: A Fast and Facile Approach toward Quantitative Yields and High Specific Surface Areas. Chem. Mater. 2010, 22, 5216–5221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- James, S.L.; Adams, C.J.; Bolm, C.; Braga, D.; Collier, P.; Friščić, T.; Grepioni, F.; Harris, K.D.M.; Hyett, G.; Jones, W.; et al. Mechanochemistry: Opportunities for New and Cleaner Synthesis. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2012, 41, 413–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Stolar, T.; Užarević, K. Mechanochemistry: An Efficient and Versatile Toolbox for Synthesis, Transformation, and Functionalization of Porous Metal–organic Frameworks. CrystEngComm 2020, 22, 4511–4525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mottillo, C.; Friščić, T. Advances in Solid-state Transformations of Coordination Bonds: From the Ball Mill to the Aging Chamber. Molecules 2017, 22, 144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Willis-Fox, N.; Rognin, E.; Aljohani, T.A.; Daly, R. Polymer Mechanochemistry: Manufacturing Is Now a Force to Be Reckoned With. Chem 2018, 4, 2499–2537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Akbulatov, S.; Boulatov, R. Experimental Polymer Mechanochemistry and Its Interpretational Frameworks. ChemPhysChem 2017, 18, 1422–1450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- May, P.A.; Moore, J.S. Polymer Mechanochemistry: Techniques to Generate Molecular Force via Elongational Flows. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2013, 42, 7497–7506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, S.-E.; Li, F.; Wang, G.-W. Mechanochemistry of Fullerenes and Related Materials. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2013, 42, 7535–7570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braga, D.; Maini, L.; Grepioni, F. Mechanochemical Preparation of Co-crystals. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2013, 42, 7638–7648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delori, A.; Friscic, T.; Jones, W.; Friščić, T.; Jones, W. The Role of Mechanochemistry and Supramolecular Design in the Development of Pharmaceutical Materials. CrystEngComm 2012, 14, 2350–2362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, D.; Loots, L.; Friščić, T. Towards Medicinal Mechanochemistry: Evolution of Milling from Pharmaceutical Solid Form Screening to the Synthesis of Active Pharmaceutical Ingredients (APIs). Chem. Commun. 2016, 52, 7760–7781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friščić, T. Supramolecular Concepts and New Techniques in Mechanochemistry: Cocrystals, Cages, Rotaxanes, Open Metal–organic Frameworks. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2012, 41, 3493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trask, A.V.; Jones, W. Crystal Engineering of Organic Cocrystals by the Solid-state Grinding Approach. Top. Curr. Chem. 2005, 254, 41–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friščič, T.; Jones, W. Recent Advances in Understanding the Mechanism of Cocrystal Formation via Grinding. Cryst. Growth Des. 2009, 9, 1621–1637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahluwalia, V.K.; Kidwai, M. Organic Synthesis in Solid State. In New Trends in Green Chemistry; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2004; pp. 189–231. [Google Scholar]

- Varma, R.S. Greener and Sustainable Trends in Synthesis of Organics and Nanomaterials. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2016, 4, 5866–5878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anastas, P.T.; Warner, J.C. Green Chemistry: Theory and Practice; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1998; ISBN 9780198502340. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, S.L.Y.; Smith, R.L.; Poliakoff, M. Principles of Green Chemistry: PRODUCTIVELY. Green Chem. 2005, 7, 761–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loupy, A. Microwaves in Organic Synthesis; Loupy, A., Ed.; WILEY-VCH Verlag GmbH & Co. KGaA: Weinheim, Germany, 2006; ISBN 3-527-31452-0. [Google Scholar]

- Leonelli, C.; Mason, T.J. Microwave and Ultrasonic Processing: Now a Realistic Option for Industry. Chem. Eng. Process. Process Intensif. 2010, 49, 885–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, D.; James, S.L.; Crawford, D.E. Solvent-free Sonochemistry as a Route to Pharmaceutical Co-crystals. Chem. Commun. 2019, 55, 5463–5466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crawford, D.E. Solvent-free Sonochemistry: Sonochemical Organic Synthesis in the Absence of a Liquid Medium. Beilstein J. Org. Chem. 2017, 13, 1850–1856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cole, J.M.; Irie, M. Solid-state Photochemistry. CrystEngComm 2016, 18, 7175–7179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, M.D. Solid-state Photochemical Reactions. Tetrahedron 1987, 43, 1211–1224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guillet, J.E. Photochemistry in the Solid Phase. Polym. Eng. Sci. 1974, 14, 482–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaupp, G. Solid-state Photochemistry: New Approaches Based on New Mechanistic Insights. Int. J. Photoenergy 2001, 3, 392659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Howard, J.L.; Cao, Q.; Browne, D.L. Mechanochemistry as an Emerging Tool for Molecular Synthesis: What Can It Offer? Chem. Sci. 2018, 9, 3080–3094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- McNaught, A.D.; Wilkinson, A. Mechano-chemical Reaction. IUPAC Compend. Chem. Terminol. 2008, 889, 7141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baláž, P.; Achimovičová, M.; Baláž, M.; Billik, P.; Cherkezova-Zheleva, Z.; Criado, J.M.; Delogu, F.; Dutková, E.; Gaffet, E.; Gotor, F.J.; et al. Hallmarks of Mechanochemistry: From Nanoparticles to Technology. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2013, 42, 7571–7637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ostwald, W. Handbuch der Allgemeinen Chemie, Band I; Akademische Verlagsgesellschaft: Leipzig, Germany, 1919. [Google Scholar]

- Takacs, L. Mechanochemistry and the Other Branches of Chemistry: Similarities and Differences. Acta Phys. Pol. A 2012, 121, 711–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Bertran, J.F. Mechanochemistry: An Overview. Pure Appl. Chem. 1999, 71, 581–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kajdas, C. General Approach to Mechanochemistry and Its Relation to Tribochemistry. In Tribology in Engineering; InTechOpen: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Martini, A.; Eder, S.J.; Dörr, N. Tribochemistry: A Review of Reactive Molecular Dynamics Simulations. Lubricants 2020, 8, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Boldyreva, E. Mechanochemistry of Inorganic and Organic Systems: What is Similar, What is Different? Chem. Soc. Rev. 2013, 42, 7719–7738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takacs, L. The First Documented Mechanochemical Reaction? J. Met. 2000, 52, 12–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beyer, M.K.; Clausen-Schaumann, H. Mechanochemistry: The Mechanical Activation of Covalent Bonds. Chem. Rev. 2005, 105, 2921–2948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takacs, L.M. Carey Lea, the First Mechanochemist. J. Mater. Sci. 2004, 39, 4987–4993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takacs, L. The Mechanochemical Reduction of AgCl with Metals: Revisiting an Experiment of M. Faraday. J. Therm. Anal. Calorim. 2007, 90, 81–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takacs, L. The Historical Development of Mechanochemistry. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2013, 42, 7649–7659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takacs, L. What is Unique about Mechanochemical Reactions? Acta Phys. Pol. A 2014, 126, 1040–1043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takacs, L.M. Carey Lea, the Father of Mechanochemistry. Bull. Hist. Chem. 2003, 28, 26–34. [Google Scholar]

- Etter, M.C. Hydrogen Bonds as Design Elements in Organic Chemistry. J. Phys. Chem. 1991, 95, 4601–4610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedireddi, V.R.; Jones, W.; Chorlton, A.P.; Docherty, R. Creation of Crystalline Supramolecular Arrays: A Comparison of Co-crystal Formation from Solution and by Solid-state Grinding. Chem. Commun. 1996, 8, 987–988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braga, D.; Giaffreda, S.L.; Curzi, M.; Maini, L.; Polito, M.; Grepioni, F. Mechanical Mixing of Molecular Crystals: A Green Route to Co-crystals and Coordination Networks. J. Therm. Anal. Calorim. 2007, 90, 115–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weyna, D.R.; Shattock, T.; Vishweshwar, P.; Zaworotko, M.J. Synthesis and Structural Characterization of Cocrystals and Pharmaceutical Cocrystals: Mechanochemistry vs. Slow Evaporation from Solution. Cryst. Growth Des. 2009, 9, 1106–1123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juribašić, M.; Užarević, K.; Gracin, D.; Ćurić, M. Mechanochemical C-H Bond Activation: Rapid and Regioselective Double Cyclopalladation Monitored by in situ Raman Spectroscopy. Chem. Commun. 2014, 50, 10287–10290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tan, D.; Mottillo, C.; Katsenis, A.D.; Štrukil, V.; Friščic, T. Development of C-N Coupling Using Mechanochemistry: Catalytic Coupling of Arylsulfonamides and Carbodiimides. Angew. Chem. 2014, 53, 9321–9324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, Y.T.; Wang, G.W. FeCl3-mediated Cyclization of [60]fullerene with N-benzhydryl Sulfonamides under High-speed Vibration Milling Conditions. Org. Lett. 2013, 15, 3408–3411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haley, R.A.; Zellner, A.R.; Krause, J.A.; Guan, H.; Mack, J. Nickel Catalysis in a High Speed Ball Mill: A Recyclable Mechanochemical Method for Producing Substituted Cyclooctatetraene Compounds. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2016, 4, 2464–2469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bučar, D.K.; Friščić, T. Professor William Jones and His Materials Chemistry Group: Innovations and Advances in the Chemistry of Solids. Cryst. Growth Des. 2019, 19, 1479–1487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trask, A.V.; Motherwell, W.D.S.; Jones, W. Solvent-Drop Grinding: Green Polymorph Control of Cocrystallisation. Chem. Commun. 2004, 890–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trask, A.V.; Shan, N.; Motherwell, W.D.S.; Jones, W.; Feng, S.; Tan, R.B.H.; Carpenter, K.J. Selective Polymorph Transformation via Solvent-drop Grinding. Chem. Commun. 2005, 880–882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trask, A.V.; Samuel Motherwell, W.D.; Jones, W. Pharmaceutical Cocrystallization: Engineering a Remedy for Caffeine Hydration. Cryst. Growth Des. 2005, 5, 1013–1021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, C.J.; Colquhoun, H.M.; Crawford, P.C.; Lusi, M.; Orpen, A.G. Solid-state Interconversions of Coordination Networks and Hydrogen-bonded Salts. Angew. Chem. 2007, 46, 1124–1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skovsgaard, S.; Bond, A.D. Co-crystallisation of Benzoic Acid Derivatives with N-containing Bases in Solution and by Mechanical Grinding: Stoichiometric Variants, Polymorphism and Twinning. CrystEngComm 2009, 11, 444–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Guo, F.; Hughes, C.E.; Browne, D.L.; Peskett, T.R.; Harris, K.D.M. Discovery of New Metastable Polymorphs in a Family of Urea Co-crystals by Solid-state Mechanochemistry. Cryst. Growth Des. 2015, 15, 2901–2907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zbačnik, M.; Nogalo, I.; Cinčić, D.; Kaitner, B. Polymorphism Control in the Mechanochemical and Solution-based Synthesis of a Thermochromic Schiff Base. CrystEngComm 2015, 17, 7870–7877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasa, D.; Jones, W. Screening for New Pharmaceutical Solid Forms Using Mechanochemistry: A Practical Guide. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2017, 117, 147–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toda, F.; Yagi, M.; Kiyoshige, K. Baeyer-Villiger Reaction in the Solid State. J. Chem. Soc. Chem. Commun. 1988, 958–959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stolle, A.; Schmidt, R.; Jacob, K. Scale-up of Organic Reactions in Ball Mills: Process Intensification with Regard to Energy Efficiency and Economy of Scale. Faraday Discuss. 2014, 170, 267–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández, J.G. C–H Bond Functionalization by Mechanochemistry. Chem. Eur. J. 2017, 23, 17157–17165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hermann, G.N.; Becker, P.; Bolm, C. Mechanochemical Iridium(III)-Catalyzed C-H Bond Amidation of Benzamides with Sulfonyl Azides under Solvent-Free Conditions in a Ball Mill. Angew. Chem. 2016, 55, 3781–3784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jörres, M.; Aceña, J.L.; Soloshonok, V.A.; Bolm, C. Asymmetric Carbon-carbon Bond Formation under Solventless Conditions in Ball Mills. ChemCatChem 2015, 7, 1265–1269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández, J.G.; Bolm, C. Altering Product Selectivity by Mechanochemistry. J. Org. Chem. 2017, 82, 4007–4019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Swinburne, A.N.; Steed, J.W. The Mechanochemical Synthesis of Podand Anion Receptors. CrystEngComm 2009, 11, 433–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aakeröy, C.B.; Chopade, P.D. Oxime Decorated Cavitands Functionalized through Solvent-assisted Grinding. Org. Lett. 2011, 13, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schneider, F.; Szuppa, T.; Stolle, A.; Ondruschka, B.; Hopf, H. Energetic Assessment of the Suzuki–Miyaura Reaction: A Curtate Life Cycle Assessment as an Easily Understandable and Applicable Tool for Reaction Optimization. Green Chem. 2009, 11, 1894–1899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ling, A.R.; Baker, J.L. XCVI.—Halogen Derivatives of Quinone. Part III. Derivatives of Quinhydrone. J. Chem. Soc. Trans. 1893, 63, 1314–1327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patil, A.O.; Curtin, D.Y.; Paul, I.C. Solid-State Formation of Quinhydrones from Their Components. Use of Solid-Solid Reactions to Prepare Compounds Not Accessible from Solution. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1984, 106, 348–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Etter, M.C.; Urbañczyk-Lipkowska, Z.; Zia-Ebrahimi, M.; Panunto, T.W. Hydrogen Bond Directed Cocrystallization and Molecular Recognition Properties of Diarylureas. J. Am. Chem. Soc 1990, 112, 8415–8426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Etter, M.C.; Adsmond, D.A. The Use of Cocrystallization as a Method of Studying Hydrogen Bond Preferences of 2-aminopyrimidine. J. Chem. Soc. Chem. Commun. 1990, 589–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribas-Arino, J.; Marx, D. Covalent Mechanochemistry: Theoretical Concepts and Computational Tools with Applications to Molecular Nanomechanics. Chem. Rev. 2012, 112, 5412–5487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boldyrev, V.V. Mechanochemistry of Inorganic Solids. Proc. Indian Natl. Sci. Acad. Part A 1986, 52, 400–417. [Google Scholar]

- Suryanarayana, C. Mechanical Alloying and Milling. Prog. Mater. Sci. 2001, 46, 1–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takacs, L.; McHenry, J.S. Temperature of the Milling Balls in Shaker and Planetary Mills. J. Mater. Sci. 2006, 41, 5246–5249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burmeister, C.F.; Kwade, A. Process Engineering with Planetary Ball Mills. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2013, 42, 7660–7667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medina, C.; Daurio, D.; Nagapudi, K.; Alvarez-Nunez, F. Manufacture of Pharmaceutical Co-crystals Using Twin Screw Extrusion: A Solvent-less and Scalable Process. J. Pharm. Sci. 2010, 99, 1693–1696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daurio, D.; Medina, C.; Saw, R.; Nagapudi, K.; Alvarez-Núñez, F. Application of Twin Screw Extrusion in the Manufacture of Cocrystals, Part I: Four Case Studies. Pharmaceutics 2011, 3, 582–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Moradiya, H.G.; Islam, M.T.; Scoutaris, N.; Halsey, S.A.; Chowdhry, B.Z.; Douroumis, D. Continuous Manufacturing of High Quality Pharmaceutical Cocrystals Integrated with Process Analytical Tools for In-Line Process Control. Cryst. Growth Des. 2016, 16, 3425–3434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crawford, D.E.; Miskimmin, C.K.G.; Albadarin, A.B.; Walker, G.; James, S.L. Organic Synthesis by Twin Screw Extrusion (TSE): Continuous, Scalable and Solvent-free. Green Chem. 2017, 19, 1507–1518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cao, Q.; Howard, J.L.; Crawford, D.E.; James, S.L.; Browne, D.L. Translating Solid State Organic Synthesis from a Mixer Mill to a Continuous Twin Screw Extruder. Green Chem. 2018, 20, 4443–4447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Crawford, D.; Casaban, J.; Haydon, R.; Giri, N.; McNally, T.; James, S.L. Synthesis by Extrusion: Continuous, Large-scale Preparation of MOFs Using Little or no Solvent. Chem. Sci. 2015, 6, 1645–1649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Crawford, D.E.; Wright, L.A.; James, S.L.; Abbott, A.P. Efficient Continuous Synthesis of High Purity Deep Eutectic Solvents by Twin Screw Extrusion. Chem. Commun. 2016, 52, 4215–4218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thorwirth, R.; Bernhardt, F.; Stolle, A.; Ondruschka, B.; Asghari, J. Switchable Selectivity during Oxidation of Anilines in a Ball Mill. Chem. Eur. J. 2010, 16, 13236–13242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Braga, D.; Grepioni, F. Reactions between or within Molecular Crystals. Angew. Chem. 2004, 43, 4002–4011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Braga, D.; D’Addario, D.; Giaffreda, S.L.; Maini, L.; Polito, M.; Grepioni, F. Intra-solid and Inter-solid Reactions of Molecular Crystals: A Green Route to Crystal Engineering. Top. Curr. Chem. 2005, 254, 71–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, G.M.J. Photodimerization in the Solid State. Pure Appl. Chem. 1971, 27, 647–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Naumov, P.; Bharadwaj, P.K. Single-crystal-to-single-crystal Transformations. CrystEngComm 2015, 17, 8775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martí-Rujas, J. Thermal Reactivity in Metal Organic Materials (MOMs): From Single-crystal-to-single-crystal Reactions and Beyond. Materials 2019, 12, 4088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rodríguez, B.; Bruckmann, A.; Rantanen, T.; Bolm, C. Solvent-free Carbon-carbon Bond Formations in Ball Mills. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2007, 349, 2213–2233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, R.; Gokus, M.K.; Pagola, S. Tetrathiafulvalene: A Gate to the Mechanochemical Mechanisms of Electron Transfer Reactions. Crystals 2020, 10, 482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trukil, V.; Fábián, L.; Reid, D.G.; Duer, M.J.; Jackson, G.J.; Eckert-Maksić, M.; Friić, T. Towards an Environmentally-friendly Laboratory: Dimensionality and Reactivity in the Mechanosynthesis of Metal-organic Compounds. Chem. Commun. 2010, 46, 9191–9193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halasz, I.; Friščić, T.; Kimber, S.A.J.; Užarević, K.; Puškarić, A.; Mottillo, C.; Julien, P.; Štrukil, V.; Honkimäki, V.; Dinnebier, R.E. Quantitative in situ and Real-time Monitoring of Mechanochemical Reactions. Faraday Discuss. 2014, 170, 203–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friščić, T.; Halasz, I.; Beldon, P.J.; Belenguer, A.M.; Adams, F.; Kimber, S.A.J.; Honkimäki, V.; Dinnebier, R.E. Real-time and in situ Monitoring of Mechanochemical Milling Reactions. Nat. Chem. 2013, 5, 66–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halasz, I.; Kimber, S.A.J.; Beldon, P.J.; Belenguer, A.M.; Adams, F.; Honkimäki, V.; Nightingale, R.C.; Dinnebier, R.E.; Friščić, T. In situ and Real-time Monitoring of Mechanochemical Milling Reactions Using Synchrotron X-ray Diffraction. Nat. Protoc. 2013, 8, 1718–1729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halasz, I.; Puškaric, A.; Kimber, S.A.J.; Beldon, P.J.; Belenguer, A.M.; Adams, F.; Honkimäki, V.; Dinnebier, R.E.; Patel, B.; Jones, W.; et al. Real-time in situ Powder X-ray Diffraction Monitoring of Mechanochemical Synthesis of Pharmaceutical Cocrystals. Angew. Chem. 2013, 52, 11538–11541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Užarević, K.; Halasz, I.; Friščić, T. Real-Time and in Situ Monitoring of Mechanochemical Reactions: A New Playground for All Chemists. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2015, 6, 4129–4140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gracin, D.; Štrukil, V.; Friščic, T.; Halasz, I.; Užarevic, K. Laboratory Real-time and in situ Monitoring of Mechanochemical Milling Reactions by Raman Spectroscopy. Angew. Chem. 2014, 53, 6193–6197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Julien, P.A.; Malvestiti, I.; Friščić, T. The Effect of Milling Frequency on a Mechanochemical Organic Reaction Monitored by in situ Raman Spectroscopy. Beilstein J. Org. Chem. 2017, 13, 2160–2168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Bowmaker, G.A. Solvent-assisted Mechanochemistry. Chem. Commun. 2013, 49, 334–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shan, N.; Toda, F.; Jones, W. Mechanochemistry and Co-crystal Formation: Effect of Solvent on Reaction Kinetics. Chem. Commun. 2002, 2372–2373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friščić, T.; Childs, S.L.; Rizvi, S.A.A.; Jones, W. The Role of Solvent in Mechanochemical and Sonochemical Cocrystal Formation: A Solubility-based Approach for Predicting Cocrystallisation Outcome. CrystEngComm 2009, 11, 418–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasa, D.; Miniussi, E.; Jones, W. Mechanochemical Synthesis of Multicomponent Crystals: One Liquid for One Polymorph? A Myth to Dispel. Cryst. Growth Des. 2016, 16, 4582–4588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pfund, L.Y.; Matzger, A.J. Towards Exhaustive and Automated High-throughput Screening for Crystalline Polymorphs. ACS Comb. Sci. 2014, 16, 309–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez-Mejías, V.; Knight, J.L.; Brooks, C.L.; Matzger, A.J. On the Mechanism of Crystalline Polymorph Selection by Polymer Heteronuclei. Langmuir 2011, 27, 7575–7579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- McClelland, A.A.; López-Mejías, V.; Matzger, A.J.; Chen, Z. Peering at a Buried Polymer-crystal Interface: Probing Heterogeneous Nucleation by Sum Frequency Generation Vibrational Spectroscopy. Langmuir 2011, 27, 2162–2165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hasa, D.; Schneider Rauber, G.; Voinovich, D.; Jones, W. Cocrystal Formation through Mechanochemistry: From Neat and Liquid-Assisted Grinding to Polymer-Assisted Grinding. Angew. Chem. 2015, 54, 7371–7375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karki, S.; Friščić, T.; Jones, W.; Motherwell, W.D.S. Screening for Pharmaceutical Cocrystal Hydrates via Neat and Liquid-assisted Grinding. Mol. Pharm. 2007, 4, 347–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batchelor, E.; Klinowski, J.; Jones, W. Crystal Engineering Using Co-crystallisation of Phenazine with Dicarboxylic Acids. J. Mater. Chem. 2000, 10, 839–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Germann, L.S.; Emmerling, S.T.; Wilke, M.; Dinnebier, R.E.; Moneghini, M.; Hasa, D. Monitoring Polymer-assisted Mechanochemical Cocrystallisation through in situ X-ray Powder Diffraction. Chem. Commun. 2020, 56, 8743–8746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thakuria, R.; Eddleston, M.D.; Chow, E.H.H.; Lloyd, G.O.; Aldous, B.J.; Krzyzaniak, J.F.; Bond, A.D.; Jones, W. Use of in situ Atomic Force Microscopy to Follow Phase Changes at Crystal Surfaces in Real Time. Angew. Chem. 2013, 52, 10541–10544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friščić, T.; Reid, D.G.; Halasz, I.; Stein, R.S.; Dinnebier, R.E.; Duer, M.J. Ion- and Liquid-assisted Grinding: Improved Mechanochemical Synthesis of Metal-organic Frameworks Reveals Salt Inclusion and Anion Templating. Angew. Chem. 2010, 49, 712–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukherjee, A.; Rogers, R.D.; Myerson, A.S. Cocrystal Formation by Ionic Liquid-assisted Grinding: Case Study with Cocrystals of Caffeine. CrystEngComm 2018, 20, 3817–3821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Smit, J.P.; Hagen, E.J. Polymorphism in Caffeine Citric Acid Cocrystals. J. Chem. Crystallogr. 2015, 45, 128–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasa, D.; Carlino, E.; Jones, W. Polymer-Assisted Grinding, a Versatile Method for Polymorph Control of Cocrystallization. Cryst. Growth Des. 2016, 16, 1772–1779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Von Colbe, J.M.B.; Felderhoff, M.; Bogdanović, B.; Schüth, F.; Weidenthaler, C. One-step Direct Synthesis of a Ti-doped Sodium Alanate Hydrogen Storage Material. Chem. Commun. 2005, 4732–4734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doppiu, S.; Schultz, L.; Gutfleisch, O. In situ Pressure and Temperature Monitoring during the Conversion of Mg into MgH2 by High-pressure Reactive Ball Milling. J. Alloys Compd. 2007, 427, 204–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Užarević, K.; Štrukil, V.; Mottillo, C.; Julien, P.A.; Puškarić, A.; Friščić, T.; Halasz, I. Exploring the Effect of Temperature on a Mechanochemical Reaction by in Situ Synchrotron Powder X-ray Diffraction. Cryst. Growth Des. 2016, 16, 2342–2347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chadwick, K.; Davey, R.; Cross, W. How Does Grinding Produce Co-crystals? Insights from the Case of Benzophenone and Diphenylamine. CrystEngComm 2007, 9, 732–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lien Nguyen, K.; Friščić, T.; Day, G.M.; Gladden, L.F.; Jones, W. Terahertz Time-domain Spectroscopy and the Quantitative Monitoring of Mechanochemical Cocrystal Formation. Nat. Mater. 2007, 6, 206–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rastogi, R.P.; Bassi, P.S.; Chadha, S.L. Mechanism of the Reaction between Hydrocarbons and Picric Acid in the Solid State. J. Phys. Chem. 1963, 67, 2569–2573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaupp, G. Solid-state Molecular Syntheses: Complete Reactions without Auxiliaries Based on the New Solid-state Mechanism. CrystEngComm 2003, 5, 117–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karimi-Jafari, M.; Padrela, L.; Walker, G.M.; Croker, D.M. Creating Cocrystals: A Review of Pharmaceutical Cocrystal Preparation Routes and Applications. Cryst. Growth Des. 2018, 18, 6370–6387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rothenberg, G.; Downie, A.P.; Raston, C.L.; Scott, J.L. Understanding Solid/Solid Organic Reactions. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2001, 123, 8701–8708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Germann, L.S.; Arhangelskis, M.; Etter, M.; Dinnebier, R.E.; Friščić, T. Challenging the Ostwald Rule of Stages in Mechanochemical Cocrystallisation. Chem. Sci. 2020, 11, 10092–10100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.; Yuan, W.; Bell, S.E.J.; James, S.L. Better Understanding of Mechanochemical Reactions: Raman Monitoring Reveals Surprisingly Simple ‘Pseudo-fluid’ Model for a Ball Milling Reaction. Chem. Commun. 2014, 50, 1585–1587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kulla, H.; Becker, C.; Michalchuk, A.A.L.; Linberg, K.; Paulus, B.; Emmerling, F. Tuning the Apparent Stability of Polymorphic Cocrystals through Mechanochemistry. Cryst. Growth Des. 2019, 19, 7271–7279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, R.; Martin Scholze, H.; Stolle, A. Temperature Progression in a Mixer Ball Mill. Int. J. Ind. Chem. 2016, 7, 181–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kulla, H.; Fischer, F.; Benemann, S.; Rademann, K.; Emmerling, F. The Effect of the Ball to Reactant Ratio on Mechanochemical Reaction Times Studied by in situ PXRD. CrystEngComm 2017, 19, 3902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, R.; Burmeister, C.F.; Baláž, M.; Kwade, A.; Stolle, A. Effect of Reaction Parameters on the Synthesis of 5-arylidene Barbituric Acid Derivatives in Ball Mills. Org. Process Res. Dev. 2015, 19, 427–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michalchuk, A.A.L.; Tumanov, I.A.; Boldyreva, E.V. Ball Size or Ball Mass-What Matters in Organic Mechanochemical Synthesis? CrystEngComm 2019, 21, 2174–2179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- McKissic, K.S.; Caruso, J.T.; Blair, R.G.; Mack, J. Comparison of Shaking vs. Baking: Further Understanding the Energetics of a Mechanochemical Reaction. Green Chem. 2014, 16, 1628–1632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tumanov, I.A.; Achkasov, A.F.; Boldyreva, E.V.; Boldyrev, V.V. Following the Products of Mechanochemical Synthesis Step by Step. CrystEngComm 2011, 13, 2213–2216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urakaev, F.K.; Boldyrev, V.V. Mechanism and Kinetics of Mechanochemical Processes in Comminuting Devices: 1. Theory. Powder Technol. 2000, 107, 93–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urakaev, F.K.; Boldyrev, V.V. Mechanism and Kinetics of Mechanochemical Processes in Comminuting Devices: 2. Applications of the Theory. Experiment. Powder Technol. 2000, 107, 197–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fox, P.G. Mechanically Initiated Chemical Reactions in Solids. J. Mater. Sci. 1975, 10, 340–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karki, S.; Friščić, T.; Jones, W. Control and Interconversion of Cocrystal Stoichiometry in Grinding: Stepwise Mechanism for the Formation of a Hydrogen-bonded Cocrystal. CrystEngComm 2009, 11, 470–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burley, J.C.; Duer, M.J.; Stein, R.S.; Vrcelj, R.M. Enforcing Ostwald’s Rule of Stages: Isolation of Paracetamol Forms III and II. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 2007, 31, 271–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerain, M.; Guinet, Y.; Correia, N.T.; Paccou, L.; Danède, F.; Hédoux, A. Polymorphism and Stability of Ibuprofen/Nicotinamide Cocrystal: The Effect of the Crystalline Synthesis Method. Int. J. Pharm. 2020, 584, 119454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berry, D.J.; Seaton, C.C.; Clegg, W.; Harrington, R.W.; Coles, S.J.; Horton, P.N.; Hursthouse, M.B.; Storey, R.; Jones, W.; Friščić, T.; et al. Applying Hot-stage Microscopy to Co-crystal Screening: A Study of Nicotinamide with Seven Active Pharmaceutical Ingredients. Cryst. Growth Des. 2008, 8, 1697–1712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dudek, M.K.; Śniechowska, J.; Wróblewska, A.; Kaźmierski, S.; Potrzebowski, M.J. Cocrystals “Divorce and Marriage”: When a Binary System Meets an Active Multifunctional Synthon in a Ball Mill. Chem. Eur. J. 2020, 26, 13264–13273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shemchuk, O.; Braga, D.; Grepioni, F. Alloying Barbituric and Thiobarbituric Acids: From Solid Solutions to a Highly Stable Keto Co-crystal Form. Chem. Commun. 2016, 52, 11815–11818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almarsson, O.; Zaworotko, M.J. Crystal Engineering of the Composition of Pharmaceutical Phases. Do Pharmaceutical Co-Crystals Represent a New Path to Improved Medicines? Chem. Commun. 2004, 1889–1896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reutzel-Edens, S. Chapter 10—Analytical Techniques and Strategies for Salt/Co-crystal Characterization. In Pharmaceutical Salts and Co-Crystals; The Royal Society of Chemistry: London, UK, 2012; pp. 212–246. ISBN 978-1-84973-158-4. [Google Scholar]

- Aakeröy, C.B.; Salmon, D.J. Building Co-crystals with Molecular Sense and Supramolecular Sensibility. CrystEngComm 2005, 7, 439–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz-Cabeza, A.J. Acid–base Crystalline Complexes and the pKa Rule. CrystEngComm 2012, 14, 6362–6365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramon, G.; Davies, K.; Nassimbeni, L.R. Structures of Benzoic Acids with Substituted Pyridines and Quinolines: Salt vs. Co-crystal Formation. CrystEngComm 2014, 16, 5802–5810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Shattock, T.R.; Arora, K.K.; Vishweshwar, P.; Zaworotko, M.J. Hierarchy of Supramolecular Synthons: Persistent Carboxylic Acid·Pyridine Hydrogen Bonds in Cocrystals That also Contain a Hydroxyl Moiety. Cryst. Growth Des. 2008, 8, 4533–4545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tothadi, S.; Shaikh, T.R.; Gupta, S.; Dandela, R.; Vinod, C.P.; Nangia, A.K. Can We Identify the Salt–Cocrystal Continuum State Using XPS? Cryst. Growth Des. 2021, 21, 735–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swapna, B.; Nangia, A. Epalrestat–Cytosine Cocrystal and Salt Structures: Attempt To Control E,Z → Z,Z Isomerization. Cryst. Growth Des. 2017, 17, 3350–3360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steiner, T.; Majerz, I.; Wilson, C.C. First O-H-N Hydrogen Bond with a Centered Proton Obtained by Thermally Induced Proton Migration. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2001, 4, 2651–2654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Losev, E.; Boldyreva, E. The Effect of Amino Acid Backbone Length on Molecular Packing: Crystalline Tartrates of Glycine, β-alanine, γ-aminobutyric Acid (GABA) and dl-α-aminobutyric Acid (AABA). Acta Crystallogr. Sect. C Struct. Chem. 2018, 74, 177–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fu, X.; Li, J.; Wang, L.; Wu, B.; Xu, X.; Deng, Z.; Zhang, H. Pharmaceutical Crystalline Complexes of Sulfamethazine with Saccharin: Same Interaction Site but Different Ionization States. RSC Adv. 2016, 6, 26474–26478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Losev, E.A.; Boldyreva, E.V. A Salt or a Co-crystal-when Crystallization Protocol Matters. CrystEngComm 2018, 20, 2299–2305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Xiong, Y.; Jiao, F.; Wang, M.; Li, H. Redefining the Term of “Cocrystal” and Broadening Its Intention. Cryst. Growth Des. 2019, 19, 1471–1478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braga, D.; Grepioni, F.; Shemchuk, O. Organic-inorganic Ionic Co-crystals: A New Class of Multipurpose Compounds. CrystEngComm 2018, 20, 2212–2220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Generally Recognized as Safe (GRAS). Available online: http://www.fda.gov/Food/IngredientsPackagingLabeling/GRAS/ (accessed on 12 November 2020).

- Singh Sekhon, B. Drug-drug Co-crystals. DARU J. Pharm. Sci 2012, 20, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Thipparaboina, R.; Kumar, D.; Chavan, R.B.; Shastri, N.R. Multidrug Co-crystals: Towards the Development of Effective Therapeutic Hybrids. Drug Discov. Today 2016, 21, 481–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thakuria, R.; Sarma, B. Drug-Drug and Drug-Nutraceutical Cocrystal/Salt as Alternative Medicine for Combination Therapy: A Crystal Engineering Approach. Crystals 2018, 8, 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kale, D.P.; Zode, S.S.; Bansal, A.K. Challenges in Translational Development of Pharmaceutical Cocrystals. J. Pharm. Sci. 2017, 106, 457–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almarsson, Ö.; Peterson, M.L.; Zaworotko, M. The A to Z of Pharmaceutical Cocrystals: A Decade of Fast-moving New Science and Patents. Pharm. Pat. Anal. 2012, 1, 313–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trask, A.V. An Overview of Pharmaceutical Cocrystals as Intellectual Property. Mol. Pharm. 2007, 4, 301–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Desiraju, G.R. The Supramolecular Synthon in Crystal Engineering—A New Organic Synthesis. Angew. Chem. 1995, 34, 2311–2327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abramov, Y.A.; Loschen, C.; Klamt, A. Rational Coformer or Solvent Selection for Pharmaceutical Cocrystallization or Desolvation. J. Pharm. Sci. 2012, 101, 3687–3697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kumar, S.; Nanda, A. Approaches to Design of Pharmaceutical Cocrystals: A Review. Mol. Cryst. Liq. Cryst. 2018, 667, 54–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernstein, J.; Davis, R.E.; Shimoni, L.; Chang, N.-L. Patterns in Hydrogen Bonding: Functionality and Graph Set Analysis in Crystals. Angew. Chem. 1995, 34, 1555–1573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehta, B.K.; Singh, S.S.; Chaturvedi, S.; Wahajuddin, M.; Thakur, T.S. Rational Coformer Selection and the Development of New Crystalline Multicomponent Forms of Resveratrol with Enhanced Water Solubility. Cryst. Growth Des. 2018, 18, 1581–1592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buddhadev, S.S.; Garala, K.C. Pharmaceutical Cocrystals—A Review. Proceedings 2020, 62, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarkar, N.; Mitra, J.; Vittengl, M.; Berndt, L.; Aakeröy, C.B. A User-friendly Application for Predicting the Outcome of Co-crystallizations. CrystEngComm 2020, 22, 6776–6779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarkar, N.; Sinha, A.S.; Aakeröy, C.B. Systematic Investigation of Hydrogen-bond Propensities for Informing Co-crystal Design and Assembly. CrystEngComm 2019, 21, 6048–6055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pindelska, E.; Sokal, A.; Kolodziejski, W. Pharmaceutical Cocrystals, Salts and Polymorphs: Advanced Characterization Techniques. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2017, 117, 111–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, Y.; Qiao, R.; He, Y.; Shi, C.; Liu, Y.; Hao, H.; Su, J.; Zhong, J. Instrumental Analytical Techniques for the Characterization of Crystals in Pharmaceutics and Foods. Cryst. Growth Des. 2017, 17, 6138–6148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thipparaboina, R.; Kumar, D.; Mittapalli, S.; Balasubramanian, S.; Nangia, A.; Shastri, N.R. Ionic, Neutral, and Hybrid Acid-Base Crystalline Adducts of Lamotrigine with Improved Pharmaceutical Performance. Cryst. Growth Des. 2015, 15, 5816–5826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbas, R.; Font-Bardia, M.; Paradkar, A.; Hunter, C.A.; Prohens, R. Combined Virtual/Experimental Multicomponent Solid Forms Screening of Sildenafil: New Salts, Cocrystals, and Hybrid Salt-Cocrystals. Cryst. Growth Des. 2018, 18, 7618–7627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coelho, A.A. TOPAS and TOPAS-Academic: An Optimization Program Integrating Computer Algebra and Crystallographic Objects Written in C++. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 2018, 51, 210–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- David, W.I.F.; Shankland, K.; Van De Streek, J.; Pidcock, E.; Motherwell, W.D.S.; Cole, J.C. DASH: A Program for Crystal Structure Determination from Powder Diffraction Data. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 2006, 39, 910–915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rycerz, L. Practical Remarks Concerning Phase Diagrams Determination on the Basis of Differential Scanning Calorimetry Measurements. J. Therm. Anal. Calorim. 2013, 113, 231–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Patrick Stahly, G. A Survey of Cocrystals Reported Prior to 2000. Cryst. Growth Des. 2009, 9, 4212–4229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, E.; Rodríguez-Hornedo, N.; Suryanarayanan, R. A Rapid Thermal Method for Cocrystal Screening. CrystEngComm 2008, 10, 665–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malamatari, M.; Ross, S.A.; Douroumis, D.; Velaga, S.P. Experimental Cocrystal Screening and Solution Based Scale-up Cocrystallization Methods. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2017, 117, 162–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bezerra Melo Figueirêdo, C.; Nadvorny, D.; Quintas de Medeiros Vieira, A.C.; Lamartine Soares Sobrinho, J.; Rolim Neto, P.J.; Lee, P.I.; Felts de La Roca Soares, M. Enhancement of Dissolution Rate through Eutectic Mixture and Solid Solution of Posaconazole and Benznidazole. Int. J. Pharm. 2017, 525, 32–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yadav, J.P.A.; Bansal, A.K.; Jain, S. Molecular Understanding and Implication of Structural Integrity in the Deformation Behavior of Binary Drug-Drug Eutectic Systems. Mol. Pharm. 2018, 15, 1917–1927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chiou, W.L.; Riegelman, S. Pharmaceutical Applications of Solid Dispersion Systems. J. Pharm. Sci. 1971, 60, 1281–1302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Skieneh, J.M.; Sathisaran, I.; Dalvi, S.V.; Rohani, S. Co-amorphous Form of Curcumin-folic Acid Dihydrate with Increased Dissolution Rate. Cryst. Growth Des. 2017, 17, 6273–6280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stevens, J.S.; Byard, S.J.; Schroeder, S.L.M. Salt or Co-Crystal? Determination of Protonation State by X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (XPS). J. Pharm. Sci. 2010, 99, 4453–4457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stevens, J.S.; Byard, S.J.; Schroeder, S.L.M. Characterization of Proton Transfer in Co-Crystals by X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (XPS). Cryst. Growth Des. 2010, 10, 1435–1442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryce, D.L. NMR Crystallography: Structure and Properties of Materials from Solid-state Nuclear Magnetic Resonance Observables. IUCrJ 2017, 4, 350–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rodrigues, M.; Baptista, B.; Lopes, J.A.; Sarraguça, M.C. Pharmaceutical Cocrystallization Techniques. Advances and Challenges. Int. J. Pharm. 2018, 547, 404–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daurio, D.; Nagapudi, K.; Li, L.; Quan, P.; Nunez, F.A. Application of Twin Screw Extrusion to the Manufacture of Cocrystals: Scale-up of AMG 517-sorbic Acid Cocrystal Production. Faraday Discuss. 2014, 170, 235–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, A.L.; Gough, T.; Dhumal, R.S.; Halsey, S.A.; Paradkar, A. Monitoring Ibuprofen-nicotinamide Cocrystal Formation during Solvent Free Continuous Cocrystallization (SFCC) Using near Infrared Spectroscopy as a PAT Tool. Int. J. Pharm. 2012, 426, 15–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michalchuk, A.A.L.; Hope, K.S.; Kennedy, S.R.; Blanco, M.V.; Boldyreva, E.V.; Pulham, C.R. Ball-free Mechanochemistry: In situ Real-time Monitoring of Pharmaceutical Co-crystal Formation by Resonant Acoustic Mixing. Chem. Commun. 2018, 54, 4033–4036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tanaka, R.; Takahashi, N.; Nakamura, Y.; Hattori, Y.; Ashizawa, K.; Otsuka, M. In-line and Real-time Monitoring of Resonant Acoustic Mixing by Near-infrared Spectroscopy Combined with Chemometric Technology for Process Analytical Technology Applications in Pharmaceutical Powder Blending Systems. Anal. Sci. 2017, 33, 41–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Am Ende, D.J.; Anderson, S.R.; Salan, J.S. Development and Scale-up of Cocrystals Using Resonant Acoustic Mixing. Org. Process Res. Dev. 2014, 18, 331–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagapudi, K.; Umanzor, E.Y.; Masui, C. High-throughput Screening and Scale-up of Cocrystals Using Resonant Acoustic Mixing. Int. J. Pharm. 2017, 521, 337–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleischman, S.G.; Kuduva, S.S.; McMahon, J.A.; Moulton, B.; Bailey Walsh, R.D.; Rodríguez-Hornedo, N.; Zaworotko, M.J. Crystal Engineering of the Composition of Pharmaceutical Phases: Multiple-Component Crystalline Solids Involving Carbamazepine. Cryst. Growth Des. 2003, 3, 909–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrison, H.; Mrozek-Morrison, M.; Toschi, J.; Luu, V.; Tan, H.; Daurio, D. High throughput Bench-top Co-crystal Screening via a Floating Foam Rack/Sonic Bath Method. Org. Process Res. Dev. 2013, 17, 533–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheney, M.L.; Weyna, D.R.; Shan, N.; Hanna, M.; Wojtas, L.; Zaworotko, M.J. Coformer Selection in Pharmaceutical Cocrystal Development: A Case Study of a Meloxicam Aspirin Cocrystal that Exhibits Enhanced Solubility and Pharmacokinetics. J. Pharm. Sci. 2011, 100, 2172–2181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friščić, T.; Jones, W. Benefits of Cocrystallisation in Pharmaceutical Materials Science: An Update. J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 2010, 62, 1547–1559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dalpiaz, A.; Pavan, B.; Ferretti, V. Can Pharmaceutical Co-crystals Provide an Opportunity to Modify the Biological Properties of Drugs? Drug Discov. Today 2017, 22, 1134–1138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Emami, S.; Siahi-Shadbad, M.; Adibkia, K.; Barzegar-Jalali, M. Recent Advances in Improving Oral Drug Bioavailability by Cocrystals. BioImpacts 2018, 8, 305–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Karki, S.; Friščić, T.; Fabián, L.; Laity, P.R.; Day, G.M.; Jones, W. Improving Mechanical Properties of Crystalline Solids by Cocrystal Formation: New Compressible Forms of Paracetamol. Adv. Mater. 2009, 21, 3905–3909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.; Li, W.; Sun, W.J.; Lu, T.; Tong, H.H.Y.; Sun, C.C.; Zheng, Y. Resveratrol Cocrystals with Enhanced Solubility and Tabletability. Int. J. Pharm. 2016, 509, 391–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grepioni, F.; Wouters, J.; Braga, D.; Nanna, S.; Fours, B.; Coquerel, G.; Longfils, G.; Rome, S.; Aerts, L.; Quere, L. Ionic Co-crystals of Racetams: Solid-state Properties Enhancement of Neutral Active Pharmaceutical Ingredients via Addition of Mg2+ and Ca2+ Chlorides. CrystEngComm 2014, 16, 5887–5896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Etter, M.C.; Choo, C.G.; Reutzel, S.M. Self-Organization of Adenine and Thymine in the Solid State. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1993, 115, 4411–4412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caira, M.R.; Nassimbeni, L.R.; Wildervanck, A.F. Selective Formation of Hydrogen Bonded Cocrystals between a Sulfonamide and Aromatic Carboxylic Acids in the Solid State. J. Chem. Soc. Perkin Trans. 1995, 2, 2213–2216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friščić, T.; Fábián, L.; Burley, J.C.; Jones, W.; Motherwell, W.D.S. Exploring Cocrystal–cocrystal Reactivity via Liquid-assisted Grinding: The Assembling of Racemic and Dismantling of Enantiomeric Cocrystals. Chem. Commun. 2006, 5009–5011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friščić, T.; Trask, A.V.; Jones, W.; Motherwell, W.D.S. Screening for Inclusion Compounds and Systematic Construction of Three-Component Solids by Liquid-Assisted Grinding. Angew. Chem. 2006, 45, 7546–7550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friščić, T.; Jones, W. Cocrystal Architecture and Properties: Design and Building of Chiral and Racemic Structures by Solid-solid Reactions. Faraday Discuss. 2007, 136, 167–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myz, S.A.; Shakhtshneider, T.P.; Fucke, K.; Fedotov, A.P.; Boldyreva, E.V.; Boldyrev, V.V.; Kuleshova, N.I. Synthesis of Co-crystals of Meloxicam with Carboxylic Acids by Grinding. Mendeleev Commun. 2009, 19, 272–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemmerer, A.; Esterhuysen, C.; Bernstein, J. Synthesis, Characterization, and Molecular Modeling of a Pharmaceutical Co-crystal: (2-chloro-4-nitrobenzoic Acid):(Nicotinamide). J. Pharm. Sci. 2010, 99, 4054–4071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammad, M.A.; Alhalaweh, A.; Velaga, S.P. Hansen Solubility Parameter as a Tool to Predict Cocrystal Formation. Int. J. Pharm. 2011, 407, 63–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rehder, S.; Klukkert, M.; Löbmann, K.A.M.; Strachan, C.J.; Sakmann, A.; Gordon, K.; Rades, T.; Leopold, C.S. Investigation of the Formation Process of Two Piracetam Cocrystals during Grinding. Pharmaceutics 2011, 3, 706–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fábián, L.; Hamill, N.; Eccles, K.S.; Moynihan, H.A.; Maguire, A.R.; McCausland, L.; Lawrence, S.E. Cocrystals of Fenamic Acids with Nicotinamide. Cryst. Growth Des. 2011, 11, 3522–3528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanphui, P.; Goud, N.R.; Khandavilli, U.B.R.; Nangia, A. Fast Dissolving Curcumin Cocrystals. Cryst. Growth Des. 2011, 11, 4135–4145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nanjwade, V.K.; Manvi, F.; Shamrez, A.; Nanjwade, B. Characterization of Prulifloxacin-Salicylic Acid Complex by IR, DSC and PXRD. J. Pharm. Biomed. Sci. 2011, 5, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Goud, N.R.; Gangavaram, S.; Suresh, K.; Pal, S.; Manjunatha, S.G.; Nambiar, S.; Nangia, A. Novel Furosemide Cocrystals and Selection of High Solubility Drug Forms. J. Pharm. Sci. 2012, 101, 664–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arenas-García, J.I.; Herrera-Ruiz, D.; Mondragón-Vásquez, K.; Morales-Rojas, H.; Höpfl, H. Modification of the Supramolecular Hydrogen-bonding Patterns of Acetazolamide in the Presence of Different Cocrystal Formers: 3:1, 2:1, 1:1, and 1:2 Cocrystals from Screening with the Structural Isomers of Hydroxybenzoic Acids, Aminobenzoic Acids, Hydroxy. Cryst. Growth Des. 2012, 12, 811–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padrela, L.; De Azevedo, E.G.; Velaga, S.P. Powder X-ray Diffraction Method for the Quantification of Cocrystals in the Crystallization Mixture. Drug Dev. Ind. Pharm. 2012, 38, 923–929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alhalaweh, A.; George, S.; Basavoju, S.; Childs, S.L.; Rizvi, S.A.A.; Velaga, S.P. Pharmaceutical Cocrystals of Nitrofurantoin: Screening, Characterization and Crystal Structure Analysis. CrystEngComm 2012, 14, 5078–5088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fucke, K.; Myz, S.A.; Shakhtshneider, T.P.; Boldyreva, E.V.; Griesser, U.J. How Good are the Crystallisation Methods for Co-crystals? A Comparative Study of Piroxicam. New J. Chem. 2012, 36, 1969–1977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tumanov, N.A.; Myz, S.A.; Shakhtshneider, T.P.; Boldyreva, E.V. Are Meloxicam Dimers Really the Structure-forming Units in the “Meloxicam-carboxylic Acid” Co-crystals Family? Relation between Crystal Structures and Dissolution Behaviour. CrystEngComm 2012, 14, 305–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eddleston, M.D.; Arhangelskis, M.; Frišcic, T.; Jones, W. Solid State Grinding as a Tool to Aid Enantiomeric Resolution by Cocrystallisation. Chem. Commun. 2012, 48, 11340–11342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suresh, K.; Goud, N.R.; Nangia, A. Andrographolide: Solving Chemical Instability an Poor Solubility by Means of Cocrystals. Chem. Asian J. 2013, 8, 3032–3041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Losev, E.A.; Mikhailenko, M.A.; Achkasov, A.F.; Boldyreva, E.V. The Effect of Carboxylic Acids on Glycine Polymorphism, Salt and Co-crystal Formation. A Comparison of Different Crystallisation Techniques. New J. Chem. 2013, 37, 1973–1981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espinosa-Lara, J.C.; Guzman-Villanueva, D.; Arenas-García, J.I.; Herrera-Ruiz, D.; Rivera-Islas, J.; Román-Bravo, P.; Morales-Rojas, H.; Höpfl, H. Cocrystals of Active Pharmaceutical Ingredients–Praziquantel in Combination with Oxalic, Malonic, Succinic, Maleic, Fumaric, Glutaric, Adipic, and Pimelic Acids. Cryst. Growth Des. 2013, 13, 169–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Losev, E.A.; Boldyreva, E.V. The Role of a Liquid in “Dry” Co-grinding: A Case Study of the Effect of Water on Mechanochemical Synthesis in a “l-serine–oxalic Acid” System. CrystEngComm 2014, 16, 3857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sládková, V.; Cibulková, J.; Eigner, V.; Šturc, A.; Kratochvíl, B.; Rohlíček, J. Application and Comparison of Cocrystallization Techniques on Trospium Chloride Cocrystals. Cryst. Growth Des. 2014, 14, 2931–2936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, J.X.; Yan, Y.; Yao, J.; Chen, J.M.; Lu, T.B. Improving the Solubility of Lenalidomide via Cocrystals. Cryst. Growth Des. 2014, 14, 3069–3077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sugandha, K.; Kaity, S.; Mukherjee, S.; Isaac, J.; Ghosh, A. Solubility Enhancement of Ezetimibe by a Cocrystal Engineering Technique. Cryst. Growth Des. 2014, 14, 4475–4486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michalchuk, A.A.L.; Tumanov, I.A.; Drebushchak, V.A.; Boldyreva, E.V. Advances in Elucidating Mechanochemical Complexities via Implementation of a Simple Organic System. Faraday Discuss. 2014, 170, 311–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tilborg, A.; Springuel, G.; Norberg, B.; Wouters, J.; Leyssens, T. How Cocrystallization Affects Solid-state Tautomerism: Stanozolol Case Study. Cryst. Growth Des. 2014, 14, 3408–3422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abourahma, H.; Shah, D.D.; Melendez, J.; Johnson, E.J.; Holman, K.T. A Tale of Two Stoichiometrically Diverse Cocrystals. Cryst. Growth Des. 2015, 15, 3101–3104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, F.; Scholz, G.; Batzdorf, L.; Wilke, M.; Emmerling, F. Synthesis, Structure Determination, and Formation of a Theobromine:oxalic Acid 2:1 Cocrystal. CrystEngComm 2015, 17, 824–829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fernandes, J.A.; Sardo, M.; Mafra, L.; Choquesillo-Lazarte, D.; Masciocchi, N. X-ray and NMR Crystallography Studies of Novel Theophylline Cocrystals Prepared by Liquid Assisted Grinding. Cryst. Growth Des. 2015, 15, 3674–3683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odiase, I.; Nicholson, C.E.; Ahmad, R.; Cooper, J.; Yufit, D.S.; Cooper, S.J. Three Cocrystals and a Cocrystal Salt of Pyrimidin-2-amine and Glutaric Acid. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. C Struct. Chem. 2015, 71, 276–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batzdorf, L.; Fischer, F.; Wilke, M.; Wenzel, K.J.; Emmerling, F. Direct in situ Investigation of Milling Reactions Using Combined X-ray Diffraction and Raman Spectroscopy. Angew. Chem. 2015, 54, 1799–1802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, F.; Joester, M.; Rademann, K.; Emmerling, F. Survival of the Fittest: Competitive Co-crystal Reactions in the Ball Mill. Chem. Eur. J. 2015, 21, 14969–14974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stepanovs, D.; Jure, M.; Kuleshova, L.N.; Hofmann, D.W.M.; Mishnev, A. Cocrystals of Pentoxifylline: In Silico and Experimental Screening. Cryst. Growth Des. 2015, 15, 3652–3660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, A.Y.; Xu, L.L.; Chen, J.M.; Lu, T.B. Solubility and Dissolution Rate Enhancement of Triamterene by a Cocrystallization Method. Cryst. Growth Des. 2015, 15, 3785–3791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saikia, B.; Bora, P.; Khatioda, R.; Sarma, B. Hydrogen Bond Synthons in the Interplay of Solubility and Membrane Permeability/Diffusion in Variable Stoichiometry Drug Cocrystals. Cryst. Growth Des. 2015, 15, 5593–5603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, S.; Choi, I.; Kim, I.W. Liquid-assisted Grinding to Prepare a Cocrystal of Adefovir Dipivoxil Thermodynamically Less Stable Than Its Neat Phase. Crystals 2015, 5, 583–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mannava, M.K.C.; Suresh, K.; Nangia, A. Enhanced Bioavailability in the Oxalate Salt of the Anti-Tuberculosis Drug Ethionamide. Cryst. Growth Des. 2016, 16, 1591–1598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]