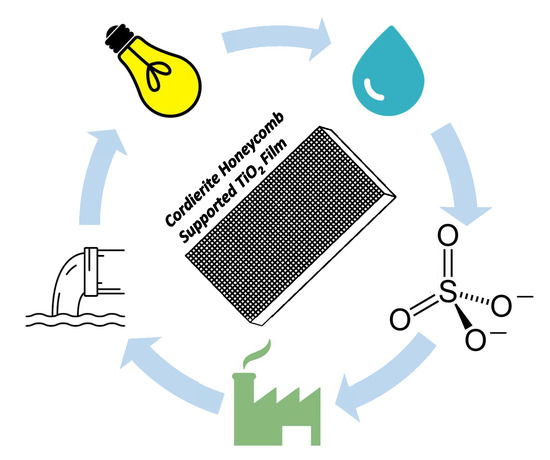

Evaluation of the Photocatalytic Activity of a Cordierite-Honeycomb-Supported TiO2 Film with a Liquid–Solid Photoreactor

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Colloid and Film Characterization

2.2. Photocatalytic Tests

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. TiO2 Nanoparticle Synthesis

3.2. Photocatalyst Immobilization on the Cordierite Honeycomb Support

3.3. Dynamic Light Scattering (DLS) Analysis of the Colloidal Nanoparticles

3.4. Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) Analysis

3.5. Raman Spectroscopy Analysis

3.6. Photodegradation Experiments

3.7. High-Performance Liquid Chromatography Analysis

3.8. Total Organic Carbon and Total Nitrogen Analysis

3.9. Wastewater Samples

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Marucco, A.; Pellegrino, F.; Oliaro-Bosso, S.; Maurino, V.; Martra, G.; Fenoglio, I. Indoor illumination: A possible pitfall in toxicological assessment of photo-active nanomaterials. J. Photochem. Photobiol. A Chem. 2018, 350, 23–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pellegrino, F.; Sordello, F.; Minella, M.; Minero, C.; Maurino, V. The Role of Surface Texture on the Photocatalytic H2 Production on TiO2. Catalysts 2019, 9, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Schneider, J.; Matsuoka, M.; Takeuchi, M.; Zhang, J.; Horiuchi, Y.; Anpo, M.; Bahnemann, D.W. Understanding TiO2 photocatalysis: Mechanisms and materials. Chem. Rev. 2014, 114, 9919–9986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Telegang Chekem, C.; Goetz, V.; Richardson, Y.; Plantard, G.; Blin, J. Modelling of adsorption/photodegradation phenomena on AC-TiO2 composite catalysts for water treatment detoxification. Catal. Today 2019, 328, 183–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, J.; Du, Y.E.; Bai, Y.; An, J.; Cai, X.; Chen, Y.; Wang, P.; Yang, X.; Feng, Q. Facile Formation of Anatase/Rutile TiO2 Nanocomposites with Enhanced Photocatalytic Activity. Molecules 2019, 24, 2996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hong, T.; Mao, J.; Tao, F.; Lan, M. Recyclable Magnetic Titania Nanocomposite from Ilmenite with Enhanced Photocatalytic Activity. Molecules 2017, 22, 2044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wei, M.; Peng, X.L.; Liu, Q.S.; Li, F.; Yao, M.M. Nanocrystalline TiO2 Composite Films for the Photodegradation of Formaldehyde and Oxytetracycline under Visible Light Irradiation. Molecules 2017, 22, 950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Qian, R.; Zong, H.; Schneider, J.; Zhou, G.; Zhao, T.; Li, Y.; Yang, J.; Bahnemann, D.W.; Pan, J.H. Charge carrier trapping, recombination and transfer during TiO2 photocatalysis: An overview. Catal. Today 2019, 335, 78–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pellegrino, F.; Zangirolami, M.; Minero, C.; Maurino, V. Portable photoreactor for on-site measurement of the activity of photocatalytic surfaces. Catal. Today 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altomare, M.; Selli, E. Effects of metal nanoparticles deposition on the photocatalytic oxidation of ammonia in TiO2 aqueous suspensions. Catal. Today 2013, 209, 127–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Fang, S.; Zheng, Y.; Sun, J.; Lv, K. Thiourea-Modified TiO2 Nanorods with Enhanced Photocatalytic Activity. Molecules 2016, 21, 181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Sraw, A.; Kaur, T.; Pandey, Y.; Sobti, A.; Wanchoo, R.K.; Toor, A.P. Fixed bed recirculation type photocatalytic reactor with TiO2 immobilized clay beads for the degradation of pesticide polluted water. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2018, 6, 7035–7043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alrousan, D.M.A.; Polo-Lopez, M.I.; Dunlop, P.S.M.; Fernandez-Ibanez, P.; Byrne, J.A. Solar photocatalytic disinfection of water with immobilised titanium dioxide in re-circulating flow CPC reactors. Appl. Catal. B-Environ. 2012, 128, 126–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arabatzis, I.M.; Antonaraki, S.; Stergiopoulos, T.; Hiskia, A.; Papaconstantinou, E.; Bernard, M.C.; Falaras, P. Preparation, characterization and photocatalytic activity of nanocrystalline thin film TiO2 catalysts towards 3,5-dichlorophenol degradation. J. Photochem. Photobiol. A-Chem. 2002, 149, 237–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchalska, M.; Surówka, M.; Hämäläinen, J.; Iivonen, T.; Leskelä, M.; Macyk, W. Photocatalytic activity of TiO2 films on Si support prepared by atomic layer deposition. Catal. Today 2015, 252, 14–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paz, Y.; Heller, A. Photo-oxidatively self-cleaning transparent titanium dioxide films on soda lime glass: The deleterious effect of sodium contamination and its prevention. J. Mater. Res. 1997, 12, 2759–2766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez, P.; Meille, V.; Pallier, S.; Al Sawah, M.A. Deposition and characterisation of TiO2 coatings on various supports for structured (photo)catalytic reactors. Appl. Catal. A-Gen. 2009, 360, 154–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pathakoti, K.; Manubolu, M.; Hwang, H.-M. Nanotechnology applications for environmental industry. In Handbook of Nanomaterials for Industrial Applications; Elsevier Inc.: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2018; pp. 894–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, D.W.; Li, F.M.; Ray, A.K. External and internal mass transfer effect on photocatalytic degradation. Catal. Today 2001, 66, 475–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Neal Tugaoen, H.; Garcia-Segura, S.; Hristovski, K.; Westerhoff, P. Compact light-emitting diode optical fiber immobilized TiO2 reactor for photocatalytic water treatment. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 613, 1331–1338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Mauro, A.; Cantarella, M.; Nicotra, G.; Pellegrino, G.; Gulino, A.; Brundo, M.V.; Privitera, V.; Impellizzeri, G. Novel synthesis of ZnO/PMMA nanocomposites for photocatalytic applications. Sci Rep 2017, 7, 40895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Project, O. European Union’s Horizon 2020 Research and Innovation Programme: 2018. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/programmes/horizon2020/en/tags/horizon-2020-research-and-innovation-programme (accessed on 8 December 2019).

- Directive 2000/60/Ec of the European Parliament and of the Council of 23 October 2000 establishing a framework for Community action in the field of water policy. 2000. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/resource.html?uri=cellar:5c835afb-2ec6-4577-bdf8-756d3d694eeb.0004.02/DOC_1&format=PDF (accessed on 8 December 2019).

- Abdullah, M.; Low, G.K.C.; Matthews, R.W. Effects of Common Inorganic Anions on Rates of Photocatalytic Oxidation of Organic-Carbon over Illuminated Titanium-Dioxide. J. Phys. Chem. 1990, 94, 6820–6825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guillard, C.; Puzenat, E.; Lachheb, H.; Houas, A.; Herrmann, J.-M. Why inorganic salts decrease the TiO2 photocatalytic efficiency. Int. J. Photoenergy 2005, 7, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wang, K.H.; Hsieh, Y.H.; Wu, C.H.; Chang, C.Y. The pH and anion effects on the heterogeneous photocatalytic degradation of o-methylbenzoic acid in TiO2 aqueous suspension. Chemosphere 2000, 40, 389–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.F.; He, Y.L.; Zhang, M.S.; Yin, Z.; Chen, Q. Raman scattering study on anatase TiO2 nanocrystals. J. Phys. D: Appl. Phys. 2000, 33, 912–916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pellegrino, F.; Pellutiè, L.; Sordello, F.; Minero, C.; Ortel, E.; Hodoroaba, V.-D.; Maurino, V. Influence of agglomeration and aggregation on the photocatalytic activity of TiO2 nanoparticles. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2017, 216, 80–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dang, T.T.T.; Le, S.T.T.; Channei, D.; Khanitchaidecha, W.; Nakaruk, A. Photodegradation mechanisms of phenol in the photocatalytic process. Res. Chem. Intermed. 2016, 42, 5961–5974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Górska, P.; Zaleska, A.; Hupka, J. Photodegradation of phenol by UV/TiO2 and Vis/N,C-TiO2 processes: Comparative mechanistic and kinetic studies. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2009, 68, 90–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anipsitakis, G.P.; Dionysiou, D.D. Radical generation by the interaction of transition metals with common oxidants. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2004, 38, 3705–3712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, J.; Li, J.; Bai, J.; Tan, X.; Zeng, Q.; Li, L.; Zhou, B. Efficient Degradation of Refractory Organics Using Sulfate Radicals Generated Directly from WO3 Photoelectrode and the Catalytic Reaction of Sulfate. Catalysts 2017, 7, 346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hu, C.; Yu, J.C.; Hao, Z.; Wong, P.K. Effects of acidity and inorganic ions on the photocatalytic degradation of different azo dyes. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2003, 46, 35–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katz, A.; McDonagh, A.; Tijing, L.; Shon, H.K. Fouling and Inactivation of Titanium Dioxide-Based Photocatalytic Systems. Crit. Rev. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2015, 45, 1880–1915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Farner Budarz, J.; Turolla, A.; Piasecki, A.F.; Bottero, J.Y.; Antonelli, M.; Wiesner, M.R. Influence of Aqueous Inorganic Anions on the Reactivity of Nanoparticles in TiO2 Photocatalysis. Langmuir: Acs J. Surf. Colloids 2017, 33, 2770–2779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ku, Y.; Lee, W.-H.; Wang, W.-Y. Photocatalytic reduction of carbonate in aqueous solution by UV/TiO2 process. J. Mol. Catal. A Chem. 2004, 212, 191–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, Y.; Bruning, H.; Liu, W.; Rijnaarts, H.; Yntema, D. Effect of dissolved natural organic matter on the photocatalytic micropollutant removal performance of TiO2 nanotube array. J. Photochem. Photobiol. A Chem. 2019, 371, 216–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, S.Y.; Wang, Y.N.; Sun, F.Q.; Wang, R.; Zhou, Y. Novel mpg-C3N4/TiO2 nanocomposite photocatalytic membrane reactor for sulfamethoxazole photodegradation. Chem. Eng. J. 2018, 337, 183–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Time | Hardness | pH | Chlorides, mg L−1 | Sulfates, mg L−1 | Conductivity | Suspended Matter |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 h | 7 °F | 9.05 | 2.3 | 155 | 2.01 mS cm−1 | Sample filtered, <1 mg/L |

| 48 h | 7 °F | 7.98 | 2.5 | 156 | 1.82 mS cm−1 | Sample filtered, <1 mg/L |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pellegrino, F.; De Bellis, N.; Ferraris, F.; Prozzi, M.; Zangirolami, M.; Petriglieri, J.R.; Schiavi, I.; Bianco-Prevot, A.; Maurino, V. Evaluation of the Photocatalytic Activity of a Cordierite-Honeycomb-Supported TiO2 Film with a Liquid–Solid Photoreactor. Molecules 2019, 24, 4499. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules24244499

Pellegrino F, De Bellis N, Ferraris F, Prozzi M, Zangirolami M, Petriglieri JR, Schiavi I, Bianco-Prevot A, Maurino V. Evaluation of the Photocatalytic Activity of a Cordierite-Honeycomb-Supported TiO2 Film with a Liquid–Solid Photoreactor. Molecules. 2019; 24(24):4499. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules24244499

Chicago/Turabian StylePellegrino, Francesco, Nicola De Bellis, Fabrizio Ferraris, Marco Prozzi, Marco Zangirolami, Jasmine R. Petriglieri, Ilaria Schiavi, Alessandra Bianco-Prevot, and Valter Maurino. 2019. "Evaluation of the Photocatalytic Activity of a Cordierite-Honeycomb-Supported TiO2 Film with a Liquid–Solid Photoreactor" Molecules 24, no. 24: 4499. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules24244499