Vitamin D Receptor Influences Intestinal Barriers in Health and Disease

Abstract

:1. Introduction

Intestinal TJs for Barrier Functions

2. Vitamin D/VDR and TJs in Intestinal Homeostasis

3. Novel Roles of Vitamin D, VDR, and TJs in Diseases

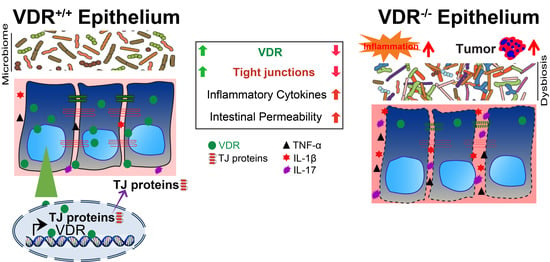

3.1. Vitamin D, VDR, and TJs in Intestinal Inflammation

3.2. Disrupted Intestinal Barrier in Colorectal Cancer (CRC)

3.3. TJs and VDR in Lungs

3.4. Infection

4. Elucidate Cellular and Molecular Mechanisms of Intestinal VDR in Regulating TJ Proteins

4.1. VDR Transcriptional Regulation of the Genes of TJ Proteins

4.2. Cellular Changes of TJs by 1,25(OH)2D3/VDR Status

4.3. Other Regulators, e.g., Probiotics and Microtome, on TJs and VDR

5. Limits and Future Directions

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| 1,25(OH)2D3 | 1,25-dihydroxy vitamin D |

| AMP | Antimicrobial Peptide |

| ATG16L1 | Autophagy Related 16 Like 1 |

| CD | Crohn’s Disease |

| COPD | Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease |

| CRC | Colorectal Cancer |

| DSS | Dextran Sulfate Sodium |

| GEO | Gene Expression Omnibus |

| GI | Gastrointestinal |

| GF | Germ-Free |

| H&E | Hematoxylin and Eosin |

| IBD | Inflammatory Bowel Disease |

| IEC | Intestinal Epithelial Cells |

| IF | Immunofluorescence |

| IHC | Immunohistochemistry |

| IL-6 | Interleukin-6 |

| IFN-γ | Interferon Gamma |

| JAM | Junctional Adhesion Molecules |

| KO | Knockout |

| LPS | Lipopolysaccharide |

| LoxP | Locus of X-over, P1 |

| MMP7 | Matrix Metalloproteinase 7 |

| MUC2 | Mucin 2 |

| NF-κB | Nuclear Factor Kappa B |

| PC | Paneth Cell |

| qRT-PCR | Quantitative Real Time Polymerase Chain Reaction |

| RXR | Retinoid X Receptor |

| TAA | Thioacetamide |

| TER | Transepithelial Electrical Resistance |

| SRA | Sequence Read Archive |

| STAT | Signal Transducer and Activator of Transcription |

| sIgA | Secretory Immunoglobulin Type A |

| TJ | Tight Junction |

| TNF-α | Tumor Necrosis Factor |

| VDR | Vitamin D Receptor |

| UC | Ulcerative Colitis |

| UTI | Urinary Tract Infection |

| ZO | Zonula Occludens |

References

- Fujita, H.; Sugimoto, K.; Inatomi, S.; Maeda, T.; Osanai, M.; Uchiyama, Y.; Yamamoto, Y.; Wada, T.; Kojima, T.; Yokozaki, H.; et al. Tight junction proteins claudin-2 and -12 are critical for vitamin D-dependent Ca2+ absorption between enterocytes. Mol. Biol. Cell 2008, 19, 1912–1921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Zhang, Y.G.; Wu, S.; Lu, R.; Zhou, D.; Zhou, J.; Carmeliet, G.; Petrof, E.; Claud, E.C.; Sun, J. Tight junction CLDN2 gene is a direct target of the vitamin D receptor. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 10642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Chatterjee, I.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, J.; Lu, R.; Xia, Y.; Sun, J. Overexpression of Vitamin D Receptor in Intestinal Epithelia Protects Against Colitis via Upregulating Tight Junction Protein Claudin 15. J. Crohns Colitis 2021, 15, 1720–1736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Garrett, S.; Carroll, R.E.; Xia, Y.; Sun, J. Vitamin D Receptor Upregulates Tight Junction Protein Claudin-5 against Tumorigenesis. bioRxiv 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.G.; Wu, S.; Sun, J. Vitamin D, Vitamin D Receptor, and Tissue Barriers. Tissue Barriers 2013, 1, e23118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Thingholm, L.B.; Skieceviciene, J.; Rausch, P.; Kummen, M.; Hov, J.R.; Degenhardt, F.; Heinsen, F.A.; Ruhlemann, M.C.; Szymczak, S.; et al. Genome-wide association analysis identifies variation in vitamin D receptor and other host factors influencing the gut microbiota. Nat. Genet. 2016, 48, 1396–1406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Becklund, B.R.; DeLuca, H.F. Identification of a highly specific and versatile vitamin D receptor antibody. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2010, 494, 166–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouillon, R.; Carmeliet, G.; Verlinden, L.; van Etten, E.; Verstuyf, A.; Luderer, H.F.; Lieben, L.; Mathieu, C.; Demay, M. Vitamin D and human health: Lessons from vitamin D receptor null mice. Endocr. Rev. 2008, 29, 726–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlberg, C.; Seuter, S. A genomic perspective on vitamin D signaling. Anticancer Res. 2009, 29, 3485–3493. [Google Scholar]

- Laukoetter, M.G.; Nava, P.; Lee, W.Y.; Severson, E.A.; Capaldo, C.T.; Babbin, B.A.; Williams, I.R.; Koval, M.; Peatman, E.; Campbell, J.A.; et al. JAM-A regulates permeability and inflammation in the intestine in vivo. J. Exp. Med. 2007, 204, 3067–3076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blikslager, A.T.; Moeser, A.J.; Gookin, J.L.; Jones, S.L.; Odle, J. Restoration of barrier function in injured intestinal mucosa. Physiol. Rev. 2007, 87, 545–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farhadi, A.; Banan, A.; Fields, J.; Keshavarzian, A. Intestinal barrier: An interface between health and disease. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2003, 18, 479–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rajapaksa, T.E.; Stover-Hamer, M.; Fernandez, X.; Eckelhoefer, H.A.; Lo, D.D. Claudin 4-targeted protein incorporated into PLGA nanoparticles can mediate M cell targeted delivery. J. Control. Release 2010, 142, 196–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ling, J.; Liao, H.; Clark, R.; Wong, M.S.; Lo, D.D. Structural constraints for the binding of short peptides to claudin-4 revealed by surface plasmon resonance. J. Biol. Chem. 2008, 283, 30585–30595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ivanov, A.I. Structure and regulation of intestinal epithelial tight junctions: Current concepts and unanswered questions. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2012, 763, 132–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ivanov, A.I.; Nusrat, A.; Parkos, C.A. The epithelium in inflammatory bowel disease: Potential role of endocytosis of junctional proteins in barrier disruption. Novartis Found Symp 2004, 263, 115–124, discussion 124–132, 211–118. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Chung, H.; Kasper, D.L. Microbiota-stimulated immune mechanisms to maintain gut homeostasis. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 2010, 22, 455–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, R.X.; Lee, J.S.; Campbell, E.L.; Colgan, S.P. Microbiota-derived butyrate dynamically regulates intestinal homeostasis through regulation of actin-associated protein synaptopodin. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2020, 117, 11648–11657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahner, C.; Mitic, L.L.; Anderson, J.M. Heterogeneity in expression and subcellular localization of claudins 2, 3, 4, and 5 in the rat liver, pancreas, and gut. Gastroenterology 2001, 120, 411–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakaguchi, T.; Gu, X.; Golden, H.M.; Suh, E.; Rhoads, D.B.; Reinecker, H.C. Cloning of the human claudin-2 5’-flanking region revealed a TATA-less promoter with conserved binding sites in mouse and human for caudal-related homeodomain proteins and hepatocyte nuclear factor-1alpha. J. Biol. Chem. 2002, 277, 21361–21370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chiba, H.; Osanai, M.; Murata, M.; Kojima, T.; Sawada, N. Transmembrane proteins of tight junctions. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2008, 1778, 588–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Rosenthal, R.; Milatz, S.; Krug, S.M.; Oelrich, B.; Schulzke, J.D.; Amasheh, S.; Gunzel, D.; Fromm, M. Claudin-2, a component of the tight junction, forms a paracellular water channel. J. Cell Sci. 2010, 123, 1913–1921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Abu-Farsakh, S.; Wu, T.; Lalonde, A.; Sun, J.; Zhou, Z. High expression of Claudin-2 in esophageal carcinoma and precancerous lesions is significantly associated with the bile salt receptors VDR and TGR5. BMC Gastroenterol. 2017, 17, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Buchert, M.; Papin, M.; Bonnans, C.; Darido, C.; Raye, W.S.; Garambois, V.; Pelegrin, A.; Bourgaux, J.F.; Pannequin, J.; Joubert, D.; et al. Symplekin promotes tumorigenicity by up-regulating claudin-2 expression. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2010, 107, 2628–2633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Dhawan, P.; Ahmad, R.; Chaturvedi, R.; Smith, J.J.; Midha, R.; Mittal, M.K.; Krishnan, M.; Chen, X.; Eschrich, S.; Yeatman, T.J.; et al. Claudin-2 expression increases tumorigenicity of colon cancer cells: Role of epidermal growth factor receptor activation. Oncogene 2011, 30, 3234–3247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Weber, C.R.; Nalle, S.C.; Tretiakova, M.; Rubin, D.T.; Turner, J.R. Claudin-1 and claudin-2 expression is elevated in inflammatory bowel disease and may contribute to early neoplastic transformation. Lab. Investig. 2008, 88, 1110–1120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zhang, Y.G.; Lu, R.; Xia, Y.; Zhou, D.; Petrof, E.; Claud, E.C.; Sun, J. Lack of Vitamin D Receptor Leads to Hyperfunction of Claudin-2 in Intestinal Inflammatory Responses. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2019, 25, 97–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.G.; Wu, S.; Xia, Y.; Sun, J. Salmonella infection upregulates the leaky protein claudin-2 in intestinal epithelial cells. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e58606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Furuse, M.; Fujita, K.; Hiiragi, T.; Fujimoto, K.; Tsukita, S. Claudin-1 and -2: Novel integral membrane proteins localizing at tight junctions with no sequence similarity to occludin. J. Cell Biol. 1998, 141, 1539–1550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angelow, S.; Ahlstrom, R.; Yu, A.S. Biology of claudins. Am. J. Physiol. Ren. Physiol. 2008, 295, F867–F876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mineta, K.; Yamamoto, Y.; Yamazaki, Y.; Tanaka, H.; Tada, Y.; Saito, K.; Tamura, A.; Igarashi, M.; Endo, T.; Takeuchi, K.; et al. Predicted expansion of the claudin multigene family. FEBS Lett. 2011, 585, 606–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Xing, T.; Benderman, L.J.; Sabu, S.; Parker, J.; Yang, J.; Lu, Q.; Ding, L.; Chen, Y.H. Tight Junction Protein Claudin-7 Is Essential for Intestinal Epithelial Stem Cell Self-Renewal and Differentiation. Cell. Mol. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2020, 9, 641–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holmes, J.L.; Van Itallie, C.M.; Rasmussen, J.E.; Anderson, J.M. Claudin profiling in the mouse during postnatal intestinal development and along the gastrointestinal tract reveals complex expression patterns. Gene Expr. Patterns 2006, 6, 581–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Demay, M.B. Mechanism of vitamin D receptor action. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2006, 1068, 204–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kato, S. The function of vitamin D receptor in vitamin D action. J. Biochem. 2000, 127, 717–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gombart, A.F.; Borregaard, N.; Koeffler, H.P. Human cathelicidin antimicrobial peptide (CAMP) gene is a direct target of the vitamin D receptor and is strongly up-regulated in myeloid cells by 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3. FASEB J. 2005, 19, 1067–1077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Wang, T.T.; Nestel, F.P.; Bourdeau, V.; Nagai, Y.; Wang, Q.; Liao, J.; Tavera-Mendoza, L.; Lin, R.; Hanrahan, J.W.; Mader, S.; et al. Cutting edge: 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 is a direct inducer of antimicrobial peptide gene expression. J. Immunol. 2004, 173, 2909–2912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wu, S.; Zhang, Y.G.; Lu, R.; Xia, Y.; Zhou, D.; Petrof, E.O.; Claud, E.C.; Chen, D.; Chang, E.B.; Carmeliet, G.; et al. Intestinal epithelial vitamin D receptor deletion leads to defective autophagy in colitis. Gut 2015, 64, 1082–1094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, D.; Zhang, Y.G.; Wu, S.; Lu, R.; Lin, Z.; Zheng, Y.; Chen, H.; Cs-Szabo, G.; Sun, J. Vitamin D receptor is a novel transcriptional regulator for Axin1. J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2017, 165, 430–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kamen, D.L.; Tangpricha, V. Vitamin D and molecular actions on the immune system: Modulation of innate and autoimmunity. J. Mol. Med. 2010, 88, 441–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Waterhouse, J.C.; Perez, T.H.; Albert, P.J. Reversing bacteria-induced vitamin D receptor dysfunction is key to autoimmune disease. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2009, 1173, 757–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, P.T.; Krutzik, S.R.; Modlin, R.L. Therapeutic implications of the TLR and VDR partnership. Trends Mol. Med. 2007, 13, 117–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kong, J.; Zhang, Z.; Musch, M.W.; Ning, G.; Sun, J.; Hart, J.; Bissonnette, M.; Li, Y.C. Novel role of the vitamin D receptor in maintaining the integrity of the intestinal mucosal barrier. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 2008, 294, G208–G216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Lagishetty, V.; Misharin, A.V.; Liu, N.Q.; Lisse, T.S.; Chun, R.F.; Ouyang, Y.; McLachlan, S.M.; Adams, J.S.; Hewison, M. Vitamin d deficiency in mice impairs colonic antibacterial activity and predisposes to colitis. Endocrinology 2010, 151, 2423–2432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gocek, E.; Studzinski, G.P. Vitamin D and differentiation in cancer. Crit. Rev. Clin. Lab. Sci. 2009, 46, 190–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Samuel, S.; Sitrin, M.D. Vitamin D’s role in cell proliferation and differentiation. Nutr. Rev. 2008, 66, S116–S124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, S.; Bruce, D.; Froicu, M.; Weaver, V.; Cantorna, M.T. Failure of T cell homing, reduced CD4/CD8alphaalpha intraepithelial lymphocytes, and inflammation in the gut of vitamin D receptor KO mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2008, 105, 20834–20839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ogura, M.; Nishida, S.; Ishizawa, M.; Sakurai, K.; Shimizu, M.; Matsuo, S.; Amano, S.; Uno, S.; Makishima, M. Vitamin D3 modulates the expression of bile acid regulatory genes and represses inflammation in bile duct-ligated mice. J. Pharm. Exp. 2009, 328, 564–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sun, J.; Kong, J.; Duan, Y.; Szeto, F.L.; Liao, A.; Madara, J.L.; Li, Y.C. Increased NF-kappaB activity in fibroblasts lacking the vitamin D receptor. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 2006, 291, E315–E322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, F.H.; Li, S.S.; Li, X.X.; Wang, S.; Li, M.G.; Guan, L.; Luan, T.G.; Liu, Z.G.; Liu, Z.J.; Yang, P.C. Vitamin D3 induces vitamin D receptor and HDAC11 binding to relieve the promoter of the tight junction proteins. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 58781–58789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Yang, H.; Jin, M.; Zhang, H.M.; Chen, X.F.; Wu, M.X.; Guo, M.Y.; Huang, C.Z.; Qian, J.M. Effects of Vitamin D Receptor on Mucosal Barrier Proteins in Colon Cells under Hypoxic Environment. Zhongguo Yi Xue Ke Xue Yuan Xue Bao 2019, 41, 506–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmer, H.G.; Gonzalez-Sancho, J.M.; Espada, J.; Berciano, M.T.; Puig, I.; Baulida, J.; Quintanilla, M.; Cano, A.; de Herreros, A.G.; Lafarga, M.; et al. Vitamin D(3) promotes the differentiation of colon carcinoma cells by the induction of E-cadherin and the inhibition of beta-catenin signaling. J. Cell Biol. 2001, 154, 369–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Lee, P.C.; Hsieh, Y.C.; Huo, T.I.; Yang, U.C.; Lin, C.H.; Li, C.P.; Huang, Y.H.; Hou, M.C.; Lin, H.C.; Lee, K.C. Active Vitamin D3 Treatment Attenuated Bacterial Translocation via Improving Intestinal Barriers in Cirrhotic Rats. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2021, 65, e2000937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ordonez-Moran, P.; Alvarez-Diaz, S.; Valle, N.; Larriba, M.J.; Bonilla, F.; Munoz, A. The effects of 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 on colon cancer cells depend on RhoA-ROCK-p38MAPK-MSK signaling. J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2010, 121, 355–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haussler, M.R.; Whitfield, G.K.; Kaneko, I.; Haussler, C.A.; Hsieh, D.; Hsieh, J.C.; Jurutka, P.W. Molecular Mechanisms of Vitamin D Action. Calcif. Tissue Int. 2012, 92, 77–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pereira, F.; Barbachano, A.; Silva, J.; Bonilla, F.; Campbell, M.J.; Munoz, A.; Larriba, M.J. KDM6B/JMJD3 histone demethylase is induced by vitamin D and modulates its effects in colon cancer cells. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2011, 20, 4655–4665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Christakos, S.; Dhawan, P.; Ajibade, D.; Benn, B.S.; Feng, J.; Joshi, S.S. Mechanisms involved in vitamin D mediated intestinal calcium absorption and in non-classical actions of vitamin D. J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2010, 121, 183–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Kutuzova, G.D.; Deluca, H.F. Gene expression profiles in rat intestine identify pathways for 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D(3) stimulated calcium absorption and clarify its immunomodulatory properties. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2004, 432, 152–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.W.; Ma, Y.Y.; Zhu, J.; Zuo, S.; Zhang, J.L.; Chen, Z.Y.; Chen, G.W.; Wang, X.; Pan, Y.S.; Liu, Y.C.; et al. Protective effect of 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 on ethanol-induced intestinal barrier injury both in vitro and in vivo. Toxicol. Lett. 2015, 237, 79–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, L.; Liu, T.; Shi, Y.; Tian, F.; Hu, H.; Deb, D.K.; Chen, Y.; Bissonnette, M.; Li, Y.C. Gut Epithelial Vitamin D Receptor Regulates Microbiota-Dependent Mucosal Inflammation by Suppressing Intestinal Epithelial Cell Apoptosis. Endocrinology 2018, 159, 967–979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zhao, H.; Zhang, H.; Wu, H.; Li, H.; Liu, L.; Guo, J.; Li, C.; Shih, D.Q.; Zhang, X. Protective role of 1,25(OH)2vitamin D3 in the mucosal injury and epithelial barrier disruption in DSS-induced acute colitis in mice. BMC Gastroenterol. 2012, 12, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Sari, E.; Oztay, F.; Tasci, A.E. Vitamin D modulates E-cadherin turnover by regulating TGF-beta and Wnt signalings during EMT-mediated myofibroblast differentiation in A459 cells. J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2020, 202, 105723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, R.; Zhao, H.; Dong, H.; Zou, F.; Cai, S. 1alpha,25-dihydroxyvitamin D(3) counteracts the effects of cigarette smoke in airway epithelial cells. Cell Immunol. 2015, 295, 137–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y.Y.; Liu, T.J.; Fu, J.H.; Xu, W.; Wu, L.L.; Hou, A.N.; Xue, X.D. Vitamin D/VDR signaling attenuates lipopolysaccharide-induced acute lung injury by maintaining the integrity of the pulmonary epithelial barrier. Mol. Med. Rep. 2016, 13, 1186–1194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Chen, H.; Lu, R.; Zhang, Y.G.; Sun, J. Vitamin D Receptor Deletion Leads to the Destruction of Tight and Adherens Junctions in Lungs. Tissue Barriers 2018, 6, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Migliori, M.; Giovannini, L.; Panichi, V.; Filippi, C.; Taccola, D.; Origlia, N.; Mannari, C.; Camussi, G. Treatment with 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 preserves glomerular slit diaphragm-associated protein expression in experimental glomerulonephritis. Int. J. Immunopathol. Pharm. 2005, 18, 779–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kladnitsky, O.; Rozenfeld, J.; Azulay-Debby, H.; Efrati, E.; Zelikovic, I. The claudin-16 channel gene is transcriptionally inhibited by 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D. Exp. Physiol. 2015, 100, 79–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elizondo, R.A.; Yin, Z.; Lu, X.; Watsky, M.A. Effect of vitamin D receptor knockout on cornea epithelium wound healing and tight junctions. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2014, 55, 5245–5251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Yin, Z.; Pintea, V.; Lin, Y.; Hammock, B.D.; Watsky, M.A. Vitamin D enhances corneal epithelial barrier function. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2011, 52, 7359–7364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Visconti, B.; Paolino, G.; Carotti, S.; Pendolino, A.L.; Morini, S.; Richetta, A.G.; Calvieri, S. Immunohistochemical expression of VDR is associated with reduced integrity of tight junction complex in psoriatic skin. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2015, 29, 2038–2042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Won, S.; Sayeed, I.; Peterson, B.L.; Wali, B.; Kahn, J.S.; Stein, D.G. Vitamin D prevents hypoxia/reoxygenation-induced blood-brain barrier disruption via vitamin D receptor-mediated NF-kB signaling pathways. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0122821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Oh, C.; Kim, H.J.; Kim, H.M. Vitamin D maintains E-cadherin intercellular junctions by downregulating MMP-9 production in human gingival keratinocytes treated by TNF-alpha. J. Periodontal. Implant Sci. 2019, 49, 270–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohanty, S.; Kamolvit, W.; Hertting, O.; Brauner, A. Vitamin D strengthens the bladder epithelial barrier by inducing tight junction proteins during E. coli urinary tract infection. Cell Tissue Res. 2020, 380, 669–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Blaney, G.P.; Albert, P.J.; Proal, A.D. Vitamin D metabolites as clinical markers in autoimmune and chronic disease. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2009, 1173, 384–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adorini, L.; Penna, G. Control of autoimmune diseases by the vitamin D endocrine system. Nat. Clin. Pract. Rheumatol. 2008, 4, 404–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grau, M.V.; Baron, J.A.; Sandler, R.S.; Haile, R.W.; Beach, M.L.; Church, T.R.; Heber, D. Vitamin D, calcium supplementation, and colorectal adenomas: Results of a randomized trial. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2003, 95, 1765–1771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heaney, R.P. Vitamin D in health and disease. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2008, 3, 1535–1541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cannell, J.J.; Hollis, B.W.; Zasloff, M.; Heaney, R.P. Diagnosis and treatment of vitamin D deficiency. Expert Opin. Pharm. 2008, 9, 107–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, F.C.; Xu, H.; El-Tanani, M.; Crowe, P.; Bingham, V. The yin and yang of vitamin D receptor (VDR) signaling in neoplastic progression: Operational networks and tissue-specific growth control. Biochem. Pharm. 2010, 79, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.G.; Lu, R.; Wu, S.; Chatterjee, I.; Zhou, D.; Xia, Y.; Sun, J. Vitamin D Receptor Protects Against Dysbiosis and Tumorigenesis via the JAK/STAT Pathway in Intestine. Cell. Mol. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2020, 10, 729–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, M.; Chan, A.T.; Sun, J. Influence of the Gut Microbiome, Diet, and Environment on Risk of Colorectal Cancer. Gastroenterology 2020, 158, 322–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corridoni, D.; Arseneau, K.O.; Cifone, M.G.; Cominelli, F. The dual role of nod-like receptors in mucosal innate immunity and chronic intestinal inflammation. Front. Immunol. 2014, 5, 317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Corridoni, D.; Arseneau, K.O.; Cominelli, F. Inflammatory bowel disease. Immunol. Lett. 2014, 161, 231–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- McNamee, E.N.; Masterson, J.C.; Veny, M.; Collins, C.B.; Jedlicka, P.; Byrne, F.R.; Ng, G.Y.; Rivera-Nieves, J. Chemokine receptor CCR7 regulates the intestinal TH1/TH17/Treg balance during Crohn’s-like murine ileitis. J. Leukoc. Biol. 2015, 97, 1011–1022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Sartor, R.B. Mechanisms of disease: Pathogenesis of Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis. Nat. Clin. Pract. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2006, 3, 390–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dresner-Pollak, R.; Ackerman, Z.; Eliakim, R.; Karban, A.; Chowers, Y.; Fidder, H.H. The BsmI vitamin D receptor gene polymorphism is associated with ulcerative colitis in Jewish Ashkenazi patients. Genet. Test. 2004, 8, 417–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simmons, J.D.; Mullighan, C.; Welsh, K.I.; Jewell, D.P. Vitamin D receptor gene polymorphism: Association with Crohn’s disease susceptibility. Gut 2000, 47, 211–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lee, Y.H.; Song, G.G. Pathway analysis of a genome-wide association study of ileal Crohn’s disease. DNA Cell Biol. 2012, 31, 1549–1554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azad, A.K.; Sadee, W.; Schlesinger, L.S. Innate immune gene polymorphisms in tuberculosis. Infect. Immun. 2012, 80, 3343–3359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Eloranta, J.J.; Wenger, C.; Mwinyi, J.; Hiller, C.; Gubler, C.; Vavricka, S.R.; Fried, M.; Kullak-Ublick, G.A. Association of a common vitamin D-binding protein polymorphism with inflammatory bowel disease. Pharm. Genom. 2011, 21, 559–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Abreu, M.T.; Kantorovich, V.; Vasiliauskas, E.A.; Gruntmanis, U.; Matuk, R.; Daigle, K.; Chen, S.; Zehnder, D.; Lin, Y.C.; Yang, H.; et al. Measurement of vitamin D levels in inflammatory bowel disease patients reveals a subset of Crohn’s disease patients with elevated 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D and low bone mineral density. Gut 2004, 53, 1129–1136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Lim, W.C.; Hanauer, S.B.; Li, Y.C. Mechanisms of disease: Vitamin D and inflammatory bowel disease. Nat. Clin. Pract. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2005, 2, 308–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sentongo, T.A.; Semaeo, E.J.; Stettler, N.; Piccoli, D.A.; Stallings, V.A.; Zemel, B.S. Vitamin D status in children, adolescents, and young adults with Crohn disease. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2002, 76, 1077–1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Bakke, D.; Sun, J. Ancient Nuclear Receptor VDR with New Functions: Microbiome and Inflammation. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2018, 24, 1149–1154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Stio, M.; Martinesi, M.; Bruni, S.; Treves, C.; d’Albasio, G.; Bagnoli, S.; Bonanomi, A.G. Interaction among vitamin D(3) analogue KH 1060, TNF-alpha, and vitamin D receptor protein in peripheral blood mononuclear cells of inflammatory bowel disease patients. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2006, 6, 1083–1092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cantorna, M.T.; Zhu, Y.; Froicu, M.; Wittke, A. Vitamin D status, 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3, and the immune system. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2004, 80, 1717S–1720S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cantorna, M.T. Vitamin D and its role in immunology: Multiple sclerosis, and inflammatory bowel disease. Prog. Biophys. Mol. Biol. 2006, 92, 60–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, J.; Qiao, G.; Zhang, Z.; Liu, S.Q.; Li, Y.C. Targeted vitamin D receptor expression in juxtaglomerular cells suppresses renin expression independent of parathyroid hormone and calcium. Kidney Int. 2008, 74, 1577–1581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Liu, P.T.; Modlin, R.L. Human macrophage host defense against Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 2008, 20, 371–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laverny, G.; Penna, G.; Vetrano, S.; Correale, C.; Nebuloni, M.; Danese, S.; Adorini, L. Efficacy of a potent and safe vitamin D receptor agonist for the treatment of inflammatory bowel disease. Immunol. Lett. 2010, 113, 49–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Chen, Y.; Golan, M.A.; Annunziata, M.L.; Du, J.; Dougherty, U.; Kong, J.; Musch, M.; Huang, Y.; Pekow, J.; et al. Intestinal epithelial vitamin D receptor signaling inhibits experimental colitis. J. Clin. Investig. 2013, 123, 3983–3996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Froicu, M.; Zhu, Y.; Cantorna, M.T. Vitamin D receptor is required to control gastrointestinal immunity in IL-10 knockout mice. Immunology 2006, 117, 310–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lechuga, S.; Ivanov, A.I. Disruption of the epithelial barrier during intestinal inflammation: Quest for new molecules and mechanisms. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Mol. Cell Res. 2017, 1864, 1183–1194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Katz, K.D.; Hollander, D.; Vadheim, C.M.; McElree, C.; Delahunty, T.; Dadufalza, V.D.; Krugliak, P.; Rotter, J.I. Intestinal permeability in patients with Crohn’s disease and their healthy relatives. Gastroenterology 1989, 97, 927–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martz, S.L.; McDonald, J.A.; Sun, J.; Zhang, Y.G.; Gloor, G.B.; Noordhof, C.; He, S.M.; Gerbaba, T.K.; Blennerhassett, M.; Hurlbut, D.J.; et al. Administration of defined microbiota is protective in a murine Salmonella infection model. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 16094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeissig, S.; Burgel, N.; Gunzel, D.; Richter, J.; Mankertz, J.; Wahnschaffe, U.; Kroesen, A.J.; Zeitz, M.; Fromm, M.; Schulzke, J.D. Changes in expression and distribution of claudin 2, 5 and 8 lead to discontinuous tight junctions and barrier dysfunction in active Crohn’s disease. Gut 2007, 56, 61–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schulzke, J.D.; Fromm, M. Tight junctions: Molecular structure meets function. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2009, 1165, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Itallie, C.M.; Holmes, J.; Bridges, A.; Anderson, J.M. Claudin-2-dependent changes in noncharged solute flux are mediated by the extracellular domains and require attachment to the PDZ-scaffold. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2009, 1165, 82–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Marchelletta, R.R.; Krishnan, M.; Spalinger, M.R.; Placone, T.W.; Alvarez, R.; Sayoc-Becerra, A.; Canale, V.; Shawki, A.; Park, Y.S.; Bernts, L.H.; et al. T cell protein tyrosine phosphatase protects intestinal barrier function by restricting epithelial tight junction remodeling. J. Clin. Investig. 2021, 131, e138230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darsigny, M.; Babeu, J.P.; Dupuis, A.A.; Furth, E.E.; Seidman, E.G.; Levy, E.; Verdu, E.F.; Gendron, F.P.; Boudreau, F. Loss of hepatocyte-nuclear-factor-4alpha affects colonic ion transport and causes chronic inflammation resembling inflammatory bowel disease in mice. PLoS ONE 2009, 4, e7609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turpin, W.; Lee, S.H.; Raygoza Garay, J.A.; Madsen, K.L.; Meddings, J.B.; Bedrani, L.; Power, N.; Espin-Garcia, O.; Xu, W.; Smith, M.I.; et al. Increased Intestinal Permeability is Associated with Later Development of Crohn’s Disease. Gastroenterology 2020, 159, 2092–2100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Kato, I. Gut microbiota, inflammation and colorectal cancer. Genes Dis. 2016, 3, 130–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Sun, J. Impact of bacterial infection and intestinal microbiome on colorectal cancer development. Chin. Med. J. 2021, 135, 400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mandle, H.B.; Jahan, F.A.; Bostick, R.M.; Baron, J.A.; Barry, E.L.; Yacoub, R.; Merrill, J.; Rutherford, R.E.; Seabrook, M.E.; Fedirko, V. Effects of supplemental calcium and vitamin D on tight-junction proteins and mucin-12 expression in the normal rectal mucosa of colorectal adenoma patients. Mol. Carcinog. 2019, 58, 1279–1290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wada, K.; Tanaka, H.; Maeda, K.; Inoue, T.; Noda, E.; Amano, R.; Kubo, N.; Muguruma, K.; Yamada, N.; Yashiro, M.; et al. Vitamin D receptor expression is associated with colon cancer in ulcerative colitis. Oncol. Rep. 2009, 22, 1021–1025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Zhu, L.; Han, J.; Li, L.; Wang, Y.; Li, Y.; Zhang, S. Claudin Family Participates in the Pathogenesis of Inflammatory Bowel Diseases and Colitis-Associated Colorectal Cancer. Front. Immunol. 2019, 10, 1441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cherradi, S.; Martineau, P.; Gongora, C.; Del Rio, M. Claudin gene expression profiles and clinical value in colorectal tumors classified according to their molecular subtype. Cancer Manag. Res. 2019, 11, 1337–1348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sun, J. Vitamin D and mucosal immune function. Curr. Opin. Gastroenterol. 2010, 26, 591–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- You, K.; Xu, X.; Fu, J.; Xu, S.; Yue, X.; Yu, Z.; Xue, X. Hyperoxia disrupts pulmonary epithelial barrier in newborn rats via the deterioration of occludin and ZO-1. Respir. Res. 2012, 13, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Overgaard, C.E.; Mitchell, L.A.; Koval, M. Roles for claudins in alveolar epithelial barrier function. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2012, 1257, 167–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Dong, H.; Zhao, H.; Song, J.; Tang, H.; Yao, L.; Liu, L.; Tong, W.; Zou, M.; Zou, F.; et al. 1,25-Dihydroxyvitamin D3 prevents toluene diisocyanate-induced airway epithelial barrier disruption. Int. J. Mol. Med. 2015, 36, 263–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, S.; Yang, J.; Hu, X.; Li, M.; Wang, Q.; Dancer, R.C.A.; Parekh, D.; Gao-Smith, F.; Thickett, D.R.; Jin, S. Vitamin D attenuates lung injury via stimulating epithelial repair, reducing epithelial cell apoptosis and inhibits TGF-beta induced epithelial to mesenchymal transition. Biochem. Pharm. 2020, 177, 113955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gorman, S.; Buckley, A.G.; Ling, K.M.; Berry, L.J.; Fear, V.S.; Stick, S.M.; Larcombe, A.N.; Kicic, A.; Hart, P.H. Vitamin D supplementation of initially vitamin D-deficient mice diminishes lung inflammation with limited effects on pulmonary epithelial integrity. Physiol. Rep. 2017, 5, e13371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DiFranco, K.M.; Mulligan, J.K.; Sumal, A.S.; Diamond, G. Induction of CFTR gene expression by 1,25(OH)2 vitamin D3, 25OH vitamin D3, and vitamin D3 in cultured human airway epithelial cells and in mouse airways. J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2017, 173, 323–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herr, C.; Greulich, T.; Koczulla, R.A.; Meyer, S.; Zakharkina, T.; Branscheidt, M.; Eschmann, R.; Bals, R. The role of vitamin D in pulmonary disease: COPD, asthma, infection, and cancer. Respir. Res. 2011, 12, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zhu, M.; Ji, Y. The Association Between Vitamin D And COPD Risk, Severity And Exacerbation: A Systematic Review And Meta-Analysis Update. Am. J. Resp. Crit. Care 2016, 193, A3496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sundar, I.K.; Rahman, I. Vitamin d and susceptibility of chronic lung diseases: Role of epigenetics. Front. Pharm. 2011, 2, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gilbert, C.R.; Arum, S.M.; Smith, C.M. Vitamin D deficiency and chronic lung disease. Can. Respir. J. 2009, 16, 75–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Jeffery, P.K. Structural and inflammatory changes in COPD: A comparison with asthma. Thorax 1998, 53, 129–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Janssens, W.; Bouillon, R.; Claes, B.; Carremans, C.; Lehouck, A.; Buysschaert, I.; Coolen, J.; Mathieu, C.; Decramer, M.; Lambrechts, D. Vitamin D deficiency is highly prevalent in COPD and correlates with variants in the vitamin D-binding gene. Thorax 2010, 65, 215–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kunisaki, K.M.; Niewoehner, D.E.; Singh, R.J.; Connett, J.E. Vitamin D status and longitudinal lung function decline in the Lung Health Study. Eur. Respir. J. 2011, 37, 238–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Sundar, I.K.; Hwang, J.W.; Wu, S.; Sun, J.; Rahman, I. Deletion of vitamin D receptor leads to premature emphysema/COPD by increased matrix metalloproteinases and lymphoid aggregates formation. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2011, 406, 127–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Ishii, M.; Yamaguchi, Y.; Isumi, K.; Ogawa, S.; Akishita, M. Transgenic Mice Overexpressing Vitamin D Receptor (VDR) Show Anti-Inflammatory Effects in Lung Tissues. Inflammation 2017, 40, 2012–2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.; He, J.; Yu, M.; Sun, J. The efficacy of vitamin D therapy for patients with COPD: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Ann. Palliat. Med. 2020, 9, 286–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehouck, A.; Mathieu, C.; Carremans, C.; Baeke, F.; Verhaegen, J.; Van Eldere, J.; Decallonne, B.; Bouillon, R.; Decramer, M.; Janssens, W. High doses of vitamin D to reduce exacerbations in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: A randomized trial. Ann. Intern. Med. 2012, 156, 105–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Martineau, A.R.; James, W.Y.; Hooper, R.L.; Barnes, N.C.; Jolliffe, D.A.; Greiller, C.L.; Islam, K.; McLaughlin, D.; Bhowmik, A.; Timms, P.M.; et al. Vitamin D3 supplementation in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (ViDiCO): A multicentre, double-blind, randomised controlled trial. Lancet Respir. Med. 2015, 3, 120–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallstrom, K.; McCormick, B.A. Salmonella Interaction with and Passage through the Intestinal Mucosa: Through the Lens of the Organism. Front. Microbiol. 2011, 2, 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Assa, A.; Vong, L.; Pinnell, L.J.; Avitzur, N.; Johnson-Henry, K.C.; Sherman, P.M. Vitamin D deficiency promotes epithelial barrier dysfunction and intestinal inflammation. J. Infect. Dis. 2014, 210, 1296–1305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Assa, A.; Vong, L.; Pinnell, L.J.; Rautava, J.; Avitzur, N.; Johnson-Henry, K.C.; Sherman, P.M. Vitamin D deficiency predisposes to adherent-invasive Escherichia coli-induced barrier dysfunction and experimental colonic injury. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2015, 21, 297–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guttman, J.A.; Finlay, B.B. Tight junctions as targets of infectious agents. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2009, 1788, 832–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kohler, H.; Sakaguchi, T.; Hurley, B.P.; Kase, B.A.; Reinecker, H.C.; McCormick, B.A. Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium regulates intercellular junction proteins and facilitates transepithelial neutrophil and bacterial passage. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 2007, 293, G178–G187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Boyle, E.C.; Brown, N.F.; Finlay, B.B. Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium effectors SopB, SopE, SopE2 and SipA disrupt tight junction structure and function. Cell Microbiol. 2006, 8, 1946–1957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bertelsen, L.S.; Paesold, G.; Marcus, S.L.; Finlay, B.B.; Eckmann, L.; Barrett, K.E. Modulation of chloride secretory responses and barrier function of intestinal epithelial cells by the Salmonella effector protein SigD. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 2004, 287, C939–C948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liao, A.P.; Petrof, E.O.; Kuppireddi, S.; Zhao, Y.; Xia, Y.; Claud, E.C.; Sun, J. Salmonella type III effector AvrA stabilizes cell tight junctions to inhibit inflammation in intestinal epithelial cells. PLoS ONE 2008, 3, e2369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.G.; Wu, S.; Xia, Y.; Sun, J. Salmonella-infected crypt-derived intestinal organoid culture system for host-bacterial interactions. Physiol. Rep. 2014, 2, e12147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chatterjee, I.; Lu, R.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, J.; Dai, Y.; Xia, Y.; Sun, J. Vitamin D receptor promotes healthy microbial metabolites and microbiome. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 7340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Zhang, Y.; Xia, Y.; Sun, J. Imbalance of the intestinal virome and altered viral-bacterial interactions caused by a conditional deletion of the vitamin D receptor. Gut Microbes 2021, 13, 1957408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Garrett, S.; Sun, J. Gastrointestinal symptoms, pathophysiology, and treatment in COVID-19. Genes Dis. 2021, 8, 385–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamshchikov, A.V.; Desai, N.S.; Blumberg, H.M.; Ziegler, T.R.; Tangpricha, V. Vitamin D for Treatment and Prevention of Infectious Diseases; A Systematic Review of Randomized Controlled Trials. Endocr. Pract. 2009, 15, 438–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Akbar, M.R.; Wibowo, A.; Pranata, R.; Setiabudiawan, B. Low serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D (vitamin D) level is associated with susceptibility to COVID-19, severity, and mortality: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Front. Nutr. 2021, 8, 131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Sadi, R.; Boivin, M.; Ma, T. Mechanism of cytokine modulation of epithelial tight junction barrier. Front. Biosci. A J. Virtual Libr. 2009, 14, 2765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Suzuki, T.; Yoshinaga, N.; Tanabe, S. Interleukin-6 (IL-6) regulates claudin-2 expression and tight junction permeability in intestinal epithelium. J. Biol. Chem. 2011, 286, 31263–31271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Wu, S.; Liao, A.P.; Xia, Y.; Li, Y.C.; Li, J.D.; Sartor, R.B.; Sun, J. Vitamin D receptor negatively regulates bacterial-stimulated NF-kappaB activity in intestine. Am. J. Pathol. 2010, 177, 686–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, S.; Xia, Y.; Liu, X.; Sun, J. Vitamin D receptor deletion leads to reduced level of IkappaBalpha protein through protein translation, protein-protein interaction, and post-translational modification. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 2010, 42, 329–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nakajima, A.; Vogelzang, A.; Maruya, M.; Miyajima, M.; Murata, M.; Son, A.; Kuwahara, T.; Tsuruyama, T.; Yamada, S.; Matsuura, M.; et al. IgA regulates the composition and metabolic function of gut microbiota by promoting symbiosis between bacteria. J. Exp. Med. 2018, 215, 2019–2034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Akhtar, S.; Wang, X.; Bu, H.-F.; Tan, X.-D. Role of MFG-E8 in protection of intestinal epithelial barrier function and attenuation of intestinal inflammation. In MFG-E8 and Inflammation; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2014; pp. 55–63. [Google Scholar]

- Bakke, D.; Chatterjee, I.; Agrawal, A.; Dai, Y.; Sun, J. Regulation of Microbiota by Vitamin D Receptor: A Nuclear Weapon in Metabolic Diseases. Nucl. Recept. Res. 2018, 5, 101377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Yoon, S.S.; Sun, J. Probiotics, nuclear receptor signaling, and anti-inflammatory pathways. Gastroenterol. Res. Pract. 2011, 2011, 971938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wu, S.; Yoon, S.; Zhang, Y.G.; Lu, R.; Xia, Y.; Wan, J.; Petrof, E.O.; Claud, E.C.; Chen, D.; Sun, J. Vitamin D receptor pathway is required for probiotic protection in colitis. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 2015, 309, G341–G349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Shang, M.; Sun, J. Vitamin D/VDR, Probiotics, and Gastrointestinal Diseases. Curr. Med. Chem. 2017, 24, 876–887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, R.; Shang, M.; Zhang, Y.G.; Jiao, Y.; Xia, Y.; Garrett, S.; Bakke, D.; Bauerl, C.; Martinez, G.P.; Kim, C.H.; et al. Lactic Acid Bacteria Isolated From Korean Kimchi Activate the Vitamin D Receptor-autophagy Signaling Pathways. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2020, 26, 1199–1211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Battistini, C.; Ballan, R.; Herkenhoff, M.E.; Saad, S.M.I.; Sun, J. Vitamin D Modulates Intestinal Microbiota in Inflammatory Bowel Diseases. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 22, 362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, S.; Huang, L.; Zhang, W.; Zhang, H. Vitamin D/VDR in Acute Kidney Injury: A Potential Therapeutic Target. Curr. Med. Chem. 2021, 28, 3865–3876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bikle, D.; Feingold, K.R.; Anawalt, B.; Boyce, A.; Chrousos, G.; de Herder, W.W.; Dhatariya, K.; Dungan, K.; Hershman, J.M.; Hofland, J.; et al. (Eds.) Vitamin D: Production, Metabolism and Mechanisms of Action; MDText.com, Inc.: South Dartmouth, MA, USA, 2000. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK278935/ (accessed on 10 February 2022).

- Bikle, D.; Adams, J.; Christakos, S. Vitamin D: Production, metabolism, mechanism of action, and clinical requirements. In Primer on the Metabolic Bone Diseases and Disorders of Mineral Metabolism; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2013; pp. 235–247. [Google Scholar]

- Sherman, M.H.; Yu, R.T.; Engle, D.D.; Ding, N.; Atkins, A.R.; Tiriac, H.; Collisson, E.A.; Connor, F.; Van Dyke, T.; Kozlov, S.; et al. Vitamin D receptor-mediated stromal reprogramming suppresses pancreatitis and enhances pancreatic cancer therapy. Cell 2014, 159, 80–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Hirano, T.; Kobayashi, N.; Itoh, T.; Takasuga, A.; Nakamaru, T.; Hirotsune, S.; Sugimoto, Y. Null mutation of PCLN-1/Claudin-16 results in bovine chronic interstitial nephritis. Genome Res. 2000, 10, 659–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wang, H.; Brown, P.C.; Chow, E.C.Y.; Ewart, L.; Ferguson, S.S.; Fitzpatrick, S.; Freedman, B.S.; Guo, G.L.; Hedrich, W.; Heyward, S.; et al. 3D cell culture models: Drug pharmacokinetics, safety assessment, and regulatory consideration. Clin. Transl. Sci. 2021, 14, 1659–1680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, R.; Zhang, Y.G.; Xia, Y.; Zhang, J.; Kaser, A.; Blumberg, R.; Sun, J. Paneth Cell Alertness to Pathogens Maintained by Vitamin D Receptors. Gastroenterology 2021, 160, 1269–1283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, R.; Zhang, Y.G.; Xia, Y.; Sun, J. Imbalance of autophagy and apoptosis in intestinal epithelium lacking the vitamin D receptor. FASEB J. 2019, 33, 11845–11856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nakamura, T. Recent progress in organoid culture to model intestinal epithelial barrier functions. Int. Immunol. 2019, 31, 13–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Altay, G.; Larrañaga, E.; Tosi, S.; Barriga, F.M.; Batlle, E.; Fernández-Majada, V.; Martínez, E. Self-organized intestinal epithelial monolayers in crypt and villus-like domains show effective barrier function. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 10140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoultz, I.; Keita, A.V. The Intestinal Barrier and Current Techniques for the Assessment of Gut Permeability. Cells 2020, 9, 1909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, R.; Wu, S.; Xia, Y.; Sun, J. The vitamin D receptor, inflammatory bowel diseases, and colon cancer. Curr. Colorectal Cancer Rep. 2012, 8, 57–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Tajik, N.; Frech, M.; Schulz, O.; Schalter, F.; Lucas, S.; Azizov, V.; Durholz, K.; Steffen, F.; Omata, Y.; Rings, A.; et al. Targeting zonulin and intestinal epithelial barrier function to prevent onset of arthritis. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 1995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

| Tissues & Cell Types | TJ Proteins | Cell Cultures In Vitro | Experimental Models In Vivo | Conclusions | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intestine | ZO-1 E-cadherin β-catenin | T84 | The expression of VDR was positively correlated with the expression of ZO-1, occluding and claudin-5 in T84 cells. | [50] | |

| DLD-1 | VDR acts as a regulator in the expression of intestinal mucosal barrier proteins under hypoxia environment. The expressions of VDR, ZO-1, occludin, claudin-1, and E-cadherin were obviously higher in vitamin D plus hypoxia group than in single vitamin D treatment group. | [51] | |||

| SW480 | 1,25(OH)2D3 induced the expression of adhesion proteins and promoted the translocation of nuclear beta-catenin and ZO-1 to the plasma membrane. | [52] | |||

| Occludin | Cirrhotic rats | Vitamin D3 treatment significantly attenuated bacterial translocation and reduced intestinal permeability in thioacetamide-induced cirrhotic rats. It upregulated the expressions of occludin in the small intestine and claudin-1 in the colon of cirrhotic rats directly independent of intrahepatic status. Vitamin D3 treatment also enriched Muribaculaceae, Bacteroidales, Allobaculum, Anaerovorax, and Ruminococcaceae. | [53] | ||

| SW480-ADH | ROCK and MSK inhibition abrogates the induction of 1,25(OH)2D3 24-hydroxylase (CYP24), E-cadherin, and vinculin, and the repression of cyclin D1 by 1,25(OH)2D3. | [54] | |||

| Caco-2 | VDR−/− Mice | 1,25(OH)2D3 enhanced TJs by increasing junction protein expression and TER and preserved the structural integrity of TJs in the presence of DSS. VDR knockdown reduced the junction proteins and TER. 1,25(OH)2D3 can stimulate epithelial cell migration in vitro. | [43] | ||

| Claudins | Caco-2 SKCO15 | VDR−/− VDRΔIEC mice | 1,25(OH)2D3 treatment upregulates claudin-2 expression in human epithelium cells. VDR deletion in intestinal epithelial cells led to significant decreased claudin-2 expression. CLDN2 gene is a direct target of the transcription factor VDR. VDR enhances claudin-2 promoter activity in a Cdx1 binding, site-dependent manner. | [2] | |

| Enteroids Caco-2 SKCO15 | VDR−/− Mice Salmonella- or DSS colitis model | In inflamed intestines of Salmonella- or DSS-induced colitis model, a lack of VDR regulation led to a robust increase of claudin-2 at the mRNA and protein levels post-infection. In inflamed intestines of ulcerative colitis patients, VDR expression was low and claudin-2 was enhanced. In inflamed VDR−/− cells, 1,25(OH)2D3 enhanced claudin-2 promoter activity through the binding sites of NF-κB and STAT. | [27] | ||

| SKCO15 | O-VDR VDR∆IEC-Mice | Reduced claudin-15 was significantly correlated with decreased VDR in human IBD. O-VDR mice showed decreased susceptibility to chemically and bacterially induced colitis and marked increased claudin-15 expression in the colon. Correspondingly, colonic claudin-15 was reduced in VDR∆IEC mice, which were susceptible to colitis. Overexpression of intestinal epithelial VDR and vitamin D treatment resulted in significantly increased claudin-15. ChIP assays identified claudin-15 gene as a direct target of VDR. | [3] | ||

| Human Colonoids SKCO15 | VDR−/− VDRΔIEC-mice | Colonic VDR expression was low and significantly correlated with a reduction in claudin-5 in human CRC patients. Lack of VDR and a reduction of claudin-5 are associated with an increased number of tumors in the VDR−/− and VDRΔIEC mice. CHIP assay identified CLDN-5 as a downstream target of the VDR signaling pathway. | [4] | ||

| Human tissue microarr-ays | Vitamin D receptor (VDR) enhanced claudin-2 expression in colon and bile salt receptors VDR and Takeda G-protein coupled receptor 5 (TGR5) were highly expressed in esophageal adenocarcinoma and pre-cancerous lesions. | [23] | |||

| 1,25(OH)2D3 induces RANKL, SPP1 (osteopontin), and BGP (osteocalcin) to govern bone mineral remodeling; TRPV6, CaBP(9k), and claudin-2 to promote intestinal calcium absorption; and TRPV5, klotho, and Npt2c to regulate renal calcium and phosphate reabsorption. | [55] | ||||

| SW480-ADH | 1,25(OH)2D3 activates the JMJD3 gene promoter and increases JMJD3 RNA in human cancer cells. JMJD3 knockdown or expression of an inactive mutant JMJD3 fragment decreased the induction by 1,25(OH)2D3 of several target genes and of an epithelial adhesive phenotype. It downregulated E-cadherin, claudin-1, and claudin-7. | [56] | |||

| calbindin-D9k−/− mutant mice | 1,25(OH)2D3 downregulates cadherin-17 and upregulates claudin-2 and claudin-12 in the intestine, suggesting that 1,25(OH)2D3 can route calcium through the paracellular path by regulating the epithelial cell junction proteins. | [57] | |||

| Caco-2 | VDR−/− mice | Claudin-2 and/or claudin-12-based TJs form paracellular Ca(2+) channels in intestinal epithelia. This study highlights a vitamin D-dependent mechanism in calcium homeostasis. | [1] | ||

| Barrier and mucosal immunity | Rat intestine | The most strongly affected gene in intestine was CYP24 with 97-fold increase at 6 h post-1,25(OH)2D3 treatment. Intestinal calcium absorption genes: TRPV5, TRPV6, calbindin D(9k), and Ca(2+) dependent ATPase all were upregulated in response to 1,25(OH)2D3, However, a 1,25-(OH)2D3 suppression of several intra- and intercellular matrix modeling proteins, such as sodium/potassium ATPase, claudin-3, aquaporin 8, cadherin 17, and RhoA, suggesting a vitamin D regulation of TJ permeability and paracellular calcium transport. Expression of several other genes related to the immune system and angiogenesis was changed in response to 1,25(OH)2D3. | [58] | ||

| Caco-2 | C57BL/6 mice | 1,25(OH)2D3 pre-treatment ameliorated the ethanol-induced barrier dysfunction, TJ disruption, phosphorylation level of MLC, and generation of ROS, compared with ethanol-exposed monolayers. Mice fed with vitamin D-sufficient diet had a higher plasma level of 25(OH)D3 and were more resistant to ethanol-induced acute intestinal barrier injury compared with the vitamin D-deficient group. | [59] | ||

| VDRΔIEC VDRΔCEC Mice TNBS- colitis model | Gut epithelial VDR deletion aggravates epithelial cell apoptosis, resulting in mucosal barrier permeability increases. | [60] | |||

| Caco-2 | DSS-colitis model | 1,25(OH)2D3 plays a protective role in mucosal barrier homeostasis by maintaining the integrity of junction complexes and in healing capacity of the colon epithelium. | [61] | ||

| Lung | E-cadherin β-catenin | A459 | Vitamin D pre-treatment reduced TGF-β and Wnt/β-catenin signaling by increasing p-VDR, protected from E-cadherin degradation and led to the regression of EMT (epithelial–mesenchymal transition)-mediated myofibroblast differentiation. | [62] | |

| 16HBE | Vitamin D is able to counteract the cigarette smoke extract-induced bronchial epithelial barrier disruption by TER (transepithelial electrical resistance) reduction inhibition, permeability increase, ERK phosphorylation increase, calpain-1 expression increase, and distribution anomalies and the cleavage of E-cadherin and β-catenin. | [63] | |||

| ZO-1 Occludin | VDR−/− WTMice | Vitamin D supplementation alleviated LPS-induced lung injury and preserved alveolar barrier function through maintenance of the pulmonary barrier by inducing expression of occludin and ZO-1 in whole lung homogenates. | [64] | ||

| Claudins | VDR−/− WT Mice | VDR−/− mice showed significantly decreased ZO-1, occludin, claudin-1, claudin-2, claudin-4, claudin-10, β-catenin, and VE-cadherin expression in the lungs tissue compared with WT mice. | [65] | ||

| Kidney | ZO-1 | Rat | Rat treated with 1,25(OH)2D3 is able to abrogate podocytes injury, detected as desmin expression and loss of nephrin and ZO-1. | [66] | |

| Claudins | HEK 293 OK | ICR mice | In kidney, 1,25(OH)2 VitD transcriptionally inhibits claudin-16 expression by a mechanism sensitive to CaSR and Mg2+. This renal effect of 1,25(OH)2 vitamin D may serve as an adaptive response to the 1,25(OH)2 vitamin D-induced increase in intestinal Mg2+ absorption. | [67] | |

| Cornea | ZO-1 Occludin | VDR−/− WT Mice | VDR−/− mice showed the decreased expression of ZO-1 and occludin, and changed ZO-distribution on corneas compared with WT mice. | [68] | |

| Corneal epithelium | Mouse, Rabbit, Human | Vitamin D enhances corneal epithelial barrier function. Cells showed increased TER, decreased IP, and increased occludin levels when cultured with 25(OH)D3 and 1,25(OH)2D3. | [69] | ||

| Skin | ZO-1 Claudins | Human Psoriatic and Normal Skin | Psoriatic skin reduced VDR, ZO-1, and claudin-1 expression compared to normal skin, and showed a significant correlation of downregulated VDR expression to claudin-1 and ZO-1. | [70] | |

| Brain | ZO-1 Occludin Claudins | End.3 | Following hypoxic injury, 1,25(OH)2D3 treatment prevented decreased barrier function, and expression of zonula occludin-1, claudin-5, and occludin. VDR mediated the protective effect of 1,25(OH)2D3 against ischemic injury-induced blood–brain barrier dysfunction in cerebral endothelial cells. | [71] | |

| Oral | ZO-1 E-cadherin β-catenin | HOK-16B | Vitamin D reinforces E-cadherin junctions by downregulating NF-κB signaling. In addition, vitamin D averts TNF-α-induced downregulation of the development of E-cadherin junctions in HGKs by decreasing the production of MMP-9, which was upregulated by TNF-α. | [72] | |

| Urinary bladder | Occludin Claudin-14 | Mouse, Human | During E. coli infection, vitamin D induced occludin and claudin-14 in mature superficial umbrella cells of the urinary bladder. Vitamin D increased cell–cell adhesion, thus consolidating the epithelial integrity during infection. | [73] |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sun, J.; Zhang, Y.-G. Vitamin D Receptor Influences Intestinal Barriers in Health and Disease. Cells 2022, 11, 1129. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells11071129

Sun J, Zhang Y-G. Vitamin D Receptor Influences Intestinal Barriers in Health and Disease. Cells. 2022; 11(7):1129. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells11071129

Chicago/Turabian StyleSun, Jun, and Yong-Guo Zhang. 2022. "Vitamin D Receptor Influences Intestinal Barriers in Health and Disease" Cells 11, no. 7: 1129. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells11071129