A Cross-Sectional Study on the Association Between Risk Factors of Toxoplasmosis and One Health Knowledge in Pakistan

- 1Department of Biosciences, COMSATS University Islamabad (CUI), Islamabad, Pakistan

- 2Department of Biological Sciences, National University of Medical Sciences (NUMS), Rawalpindi, Pakistan

- 3Department of Parasitology, Firat University, Elazig, Turkey

- 4Department of Life Sciences, Faculty of Science, University of Management and Technology (UMT), Lahore, Pakistan

- 5Department of Wildlife and Ecology, University of Veterinary and Animal Sciences, Lahore, Pakistan

- 6National Institute of Parasitic Diseases, Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention (Chinese Center for Tropical Diseases Research), Shanghai, China

- 7Key Laboratory of Parasite and Vector Biology, National Health Commission of People's Republic of China, Shanghai, China

- 8World Health Organization (WHO) Collaborating Centre for Tropical Diseases, Shanghai, China

- 9The School of Global Health, Chinese Center for Tropical Diseases Research, Shanghai Jiao Tong University School of Medicine, Shanghai, China

Toxoplasmosis is a zoonotic disease caused by Toxoplasma gondii, a protozoan that infects warm-blooded animals and humans. Approximately one third of the global population is infected by T. gondii. We conducted a cross-sectional study to assess the risk factors and One Health knowledge of toxoplasmosis in Rawalpindi and Islamabad, Pakistan. From July through December 2020, we collected data using questionnaires. The results showed that 60% of participants had heard or read about the disease, 23.3% of participants had no knowledge about the disease, and 16.8% participants were not sure about the disease. More than half of the participants (53.3%) reported that toxoplasmosis was caused by toxins, 5.3% reported that toxoplasmosis was an animal disease, 13.8% reported that toxoplasmosis was a human disease, 65.8% reported that it was both an animal and human disease, and 15.3% reported that it was neither an animal nor a human disease. Approximately 80.5% of participants reported that individuals acquired toxoplasmosis by changing cat litter. Our study findings revealed a low level of knowledge and awareness about toxoplasmosis among males. Therefore, there should be awareness programs to educate individuals about the risks of this deadly disease and to provide information on the major routes of transmission.

Introduction

Toxoplasmosis is a zoonotic disease caused by the intracellular protozoan Toxoplasma gondii (1). T. gondii is an obligate intracellular parasite that naturally exists in one of three forms: (1) oocysts, which release sporozoites, are only produced in the small intestines of cats and are released into the environment through their feces; (2) tissue cysts, which release bradyzoites; and (3) tachyzoites, which are the proliferative form (2). Type I, II, and III strains of T. gondii have been identified in Europe, parts of Asia, and US where type II strain is mostly involved in human toxoplasmosis (3). Type I and type III strains are prevalent in Central and South America (4). Approximately 33% of the total human population has been affected by T. gondii (1). Countries in North America, Southeast Asia, Northern Europe, and Saharan African have low prevalence rates (10% to 30%), Central and Southern Europe have moderate prevalence rates (30% to 50%), and tropical African countries and Latin America have high prevalence rates of toxoplasmosis (5). The seroprevalence of toxoplasmosis was 29.45% from Southern Punjab, Pakistan (6). In Pakistan, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa has 40.6% of the seroprevalence of toxoplasmosis in women with poor obstetric history (7).

In humans, toxoplasmosis is transmitted by consuming raw or inadequately cooked meat (8), by inadvertently ingesting oocysts passed into feces by cats, either in a cat litter box or outdoors in the soil (9), and from mother to her unborn fetus (10). T. gondii infection, which is a life-threatening disease, results in retinal infection in both healthy and immunocompromised individuals (11). In immunocompromised individuals, toxoplasmosis is mostly asymptomatic (12); however, 10% of those infected may develop lymphadenitis, ocular toxoplasmosis (chorioretinitis), and mild flu-like and/or mononucleosis-like symptoms (13).

Due to their non-specificity, the clinical symptoms of toxoplasmosis are not reliable for diagnosis. While traditional diagnostic methods are based on serological tests and bioassays, a variety of molecular methods have been recently used for diagnosis of toxoplasmosis (14). Some of the diagnostic tests for toxoplasmosis include microscopy (15), bioassays (16), dye test (17), modified agglutination test (18), latex agglutination test (19), indirect hemagglutination test (20), indirect fluorescent antibody test (21), enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (22), immunosorbent agglutination assay (23), immunochromatographic test (24), piezoelectric immunoagglutination assay (25), Western blot (26), and avidity test (27). Pharmaceutical interventions against toxoplasmosis include either a combination of pyrimethamine and sulfadiazine with folic acid or a combination of pyrimethamine and macrolide antibiotics or lincosamide. For congenital toxoplasmosis, pregnant women are treated with spiramycin (12).

Toxoplasmosis, which affects both animals and humans, causes major economic losses (28). In the livestock sector of Pakistan, different diseases cause annual economic loss of 79 billion Pakistani rupees (PKR) (29). Despite having such significant impact, very few studies have explored the prevalence of toxoplasmosis in Pakistan. Therefore, we conducted a study to determine the knowledge, attitudes, and practices of toxoplasmosis among university students of twin cities, Rawalpindi and Islamabad, Pakistan.

Results

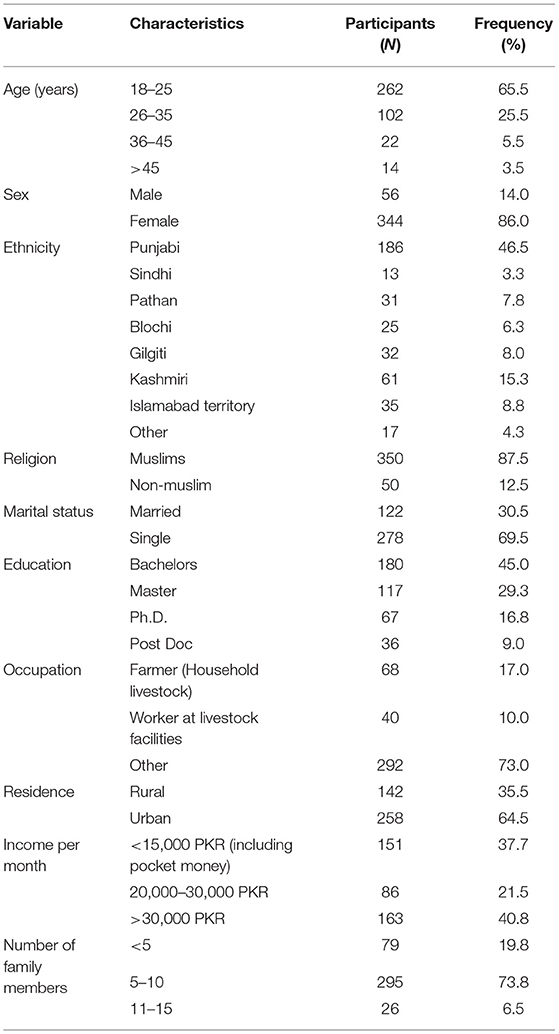

Socio-Demographic Characteristics

Table 1 presents the sociodemographic characteristics of the participants (n = 400). Most of the participants (86%) were females. The majority of the participants (65.5%) were 18 to 25 years of age, 25.5% were 26 to 35 years of age, 5.5% were 36 to 45 years of age. Among the participants, 46.5% were from Punjabi, 15.3% were from Kashmiri, 7.8% were from Pathan, and 8% were from ethnicity. Approximately, 45% of the participants were in a Bachelor's program, 29.3% were in a master's program, 16.8% were in a PhD program.

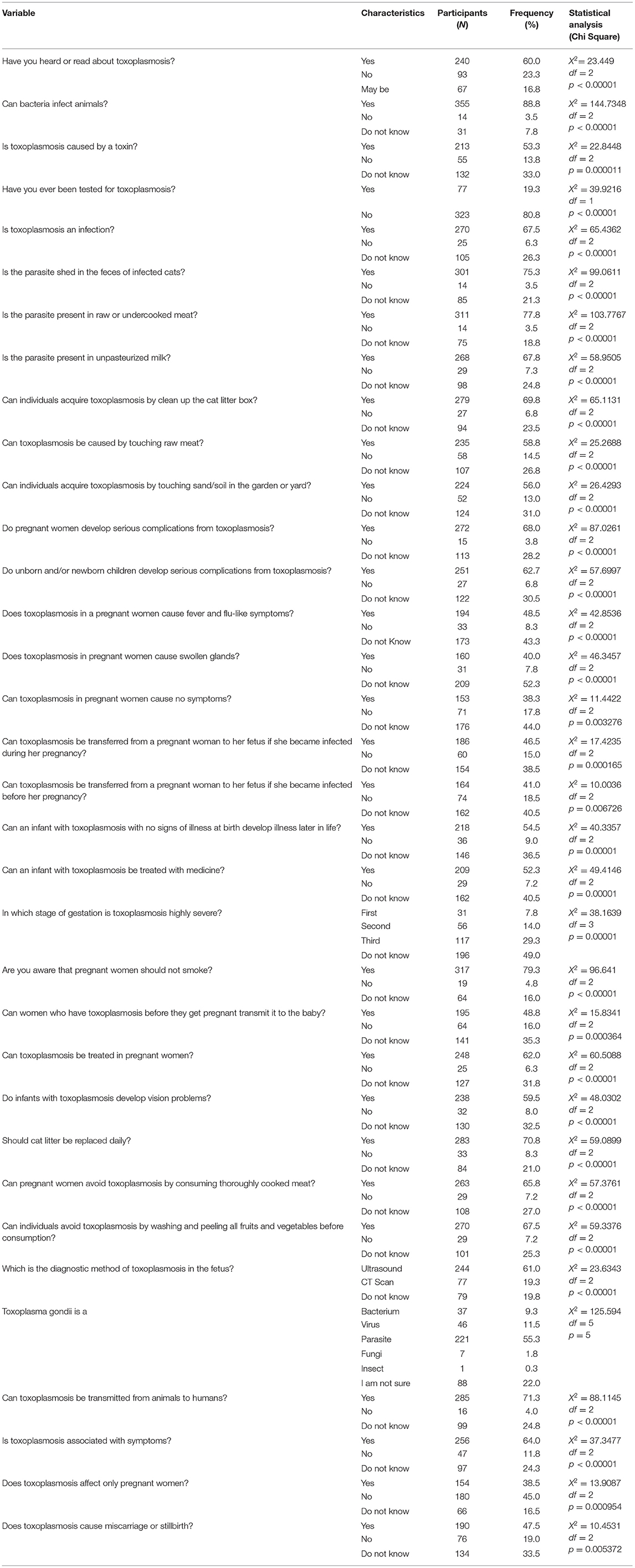

Knowledge on Toxoplasmosis

Among the participants, 60% had heard or read about the disease, 23.3% had no knowledge about the disease, and 16.8% were not sure about the disease. We performed Chi square test to assess the relationship among the categorical variables. Out of 400 participants, 53.3% reported that toxoplasmosis was caused by a toxin, 13.8% reported that toxoplasmosis was not caused by a toxin, and 33% had no knowledge on the cause of toxoplasmosis. Only a limited (19.3%) number of participants had been tested for toxoplasmosis, 67.5% of the participants were aware that toxoplasmosis was caused by an infection, and 26.3% reported that they had no knowledge on the causes of toxoplasmosis. The majority (69.8%) of the participants thought that a transmission source was cat feces, and 75.3% were aware that parasites were shed in the feces of infected cats. Approximately 58.5% of the participants reported that toxoplasmosis could be caused by touching raw meat and contaminated soil/sand and 26.8% of the participants had no knowledge about this. A significant number (68%) of participants reported that pregnant women could develop serious complications from toxoplasmosis, and 48.5% reported that the fetus and newborn could develop serious complications from toxoplasmosis. The majority (71.3%) of the participants reported that toxoplasmosis was transmitted from animals to humans, and 64% of the participants believed that toxoplasmosis is symptomatic. Approximately 47.5% of the participants reported that toxoplasmosis could cause miscarriages or stillbirth (Table 2).

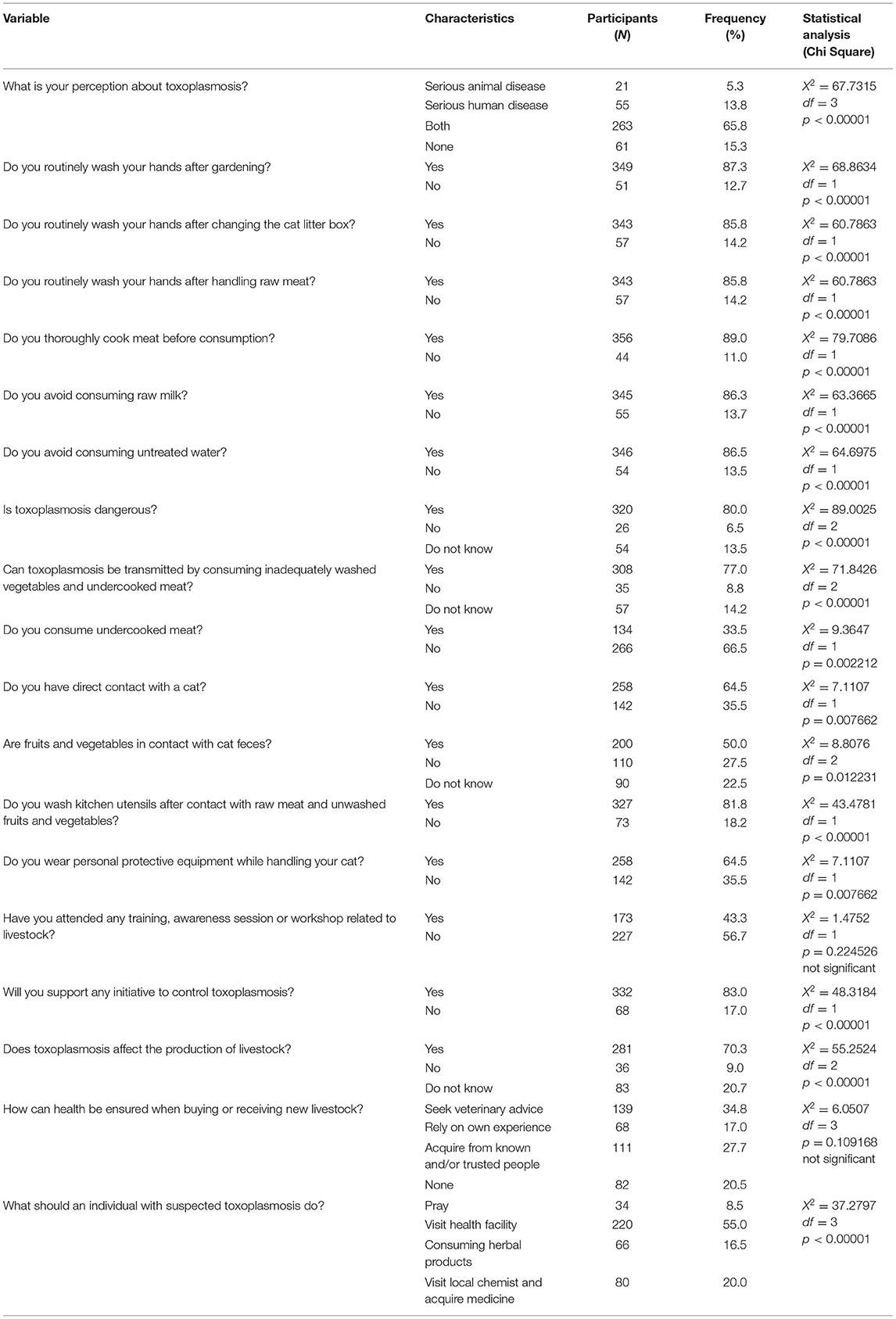

Attitudes Toward Toxoplasmosis

Among the participants, 5.3% believed that toxoplasmosis was an animal disease, 13.8% thought that toxoplasmosis was a human disease, 65.8% thought it was both an animal and human disease, and 15.3% thought it was not either of them. Most of the participants (87.3%) routinely washed their hands after gardening. Approximately, 85.8% of the participants washed their hands after changing the cat litter and after handling raw meat. Most of the participants (89%) cooked meat wel-prior to consumption, and 86.3% avoided raw milk. A significant number of participants (86.5%) reported consuming untreated water, and the majority (80%) of the participants considered toxoplasmosis to be a dangerous disease. A small number (33.5%) of participants had consumed undercooked meat, and 64.5% had direct contact with cats. Approximately, 56.7% of participants had attended training related to livestock. A significant number (83%) of participants supported initiatives for the control of toxoplasmosis. There were no significant differences in the results when asked how health should be ensured when buying or receiving new livestock. Approximately 55% of the participants thought that toxoplasmosis-suspected cases should seek the advice of healthcare providers (Table 3).

Practices Toward Toxoplasmosis

Most of the participants (71%) fed their cats dry or commercial cat food and did not let their cats kill and eat rodents. Approximately, 61.8% of the participants reported that they avoided stray cats, and 70% of the participants did not allow someone else change the cat litter box. A significant number (83.3%) of participants boiled milk before consumption, and 87.8% ensured their houses were free of waste. Most participants (86.5%) kept foods covered in containers, and 78.3% separated sick animals from healthy ones. A significant number (72.8%) of participants used protective clothes while handling livestock (Table 4).

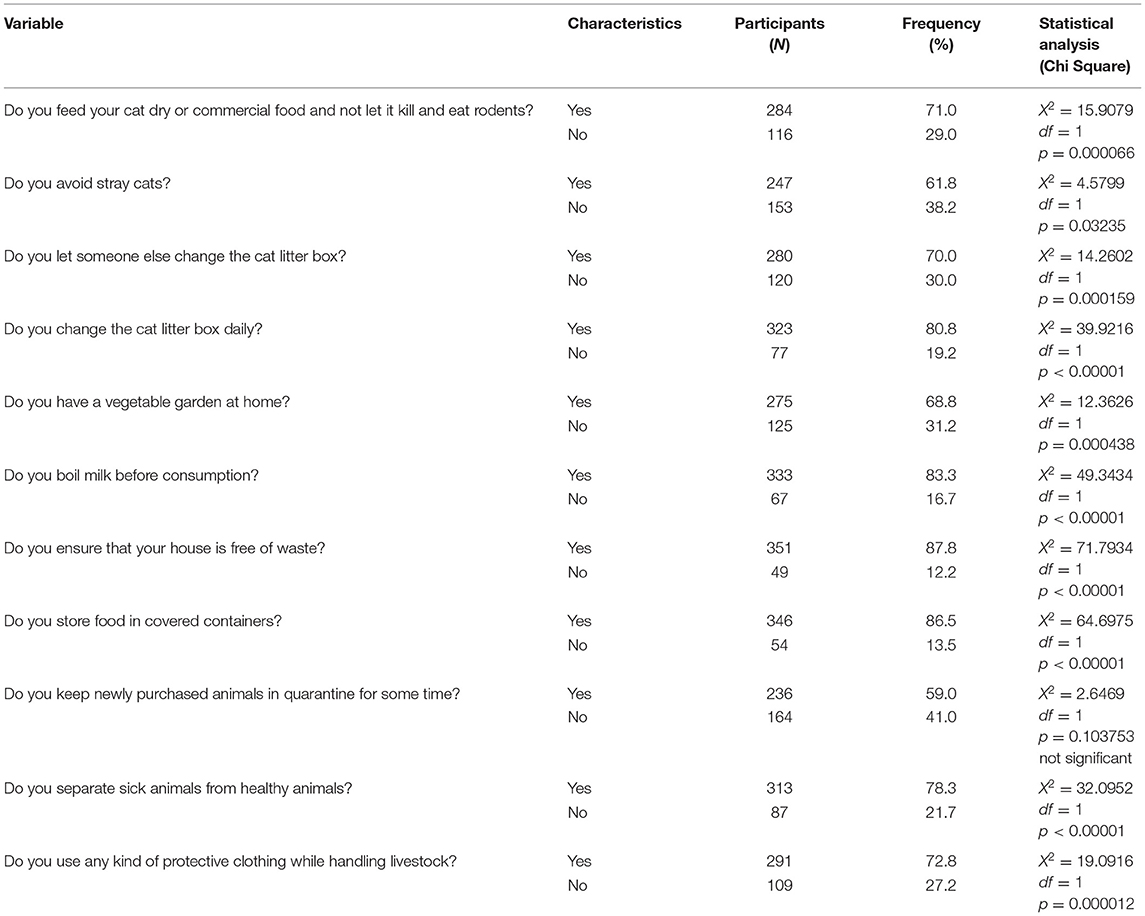

Risk Factors Associated With Toxoplasmosis

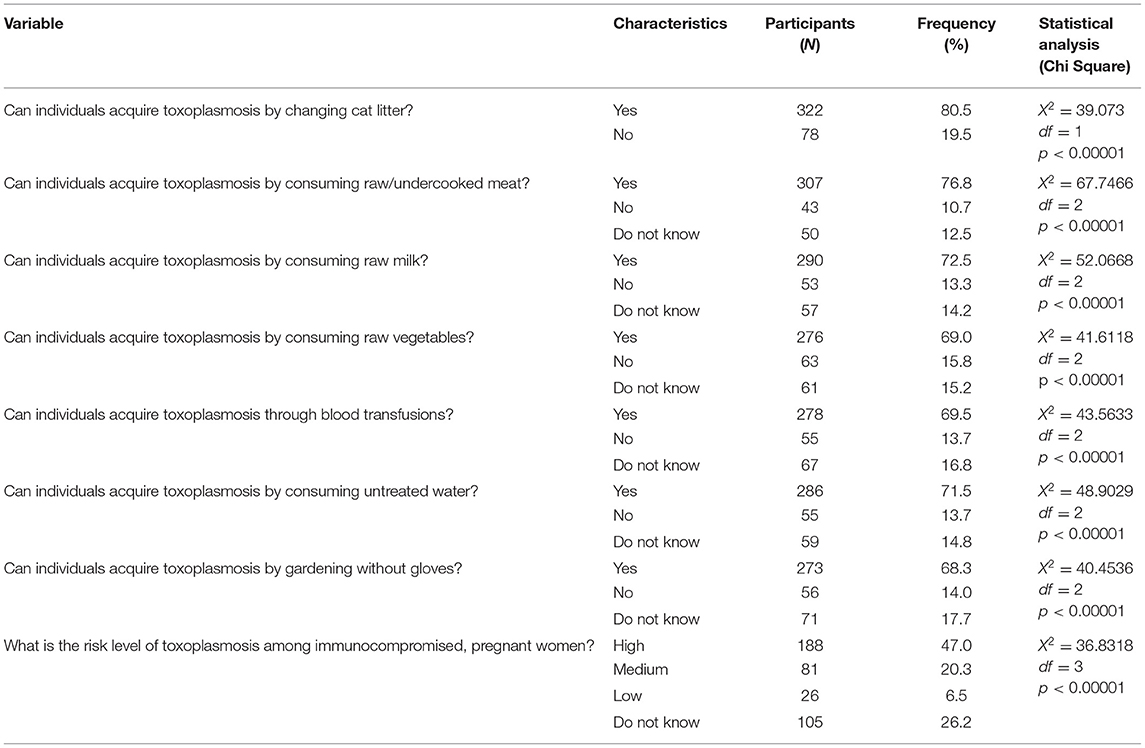

A significant number (80.5%) of participants thought that individuals could acquire toxoplasmosis by changing the cat litter, and 76.8% of participants responded that individuals could acquire toxoplasmosis by consuming raw/undercooked meat. Most participants (72.5%) believed that individuals could get toxoplasmosis by consuming raw milk, while 14.2% were not aware of this. Among the participants, 69.5% considered blood transfusion to be cause of toxoplasmosis, 13.7% considered that blood transfusion was not a cause of toxoplasmosis, and 16.8% had no knowledge about this. A significant number (68.3%) of participants thought toxoplasmosis could be transmitted by gardening without gloves. Among the participants, 47% believed that immunocompromised, pregnant women were at high risk of toxoplasmosis, 20.3% believed that pregnant women had a moderate risk of toxoplasmosis, 6.5% people reported that pregnant women had a low risk of toxoplasmosis, and 26.2% had no knowledge (Table 5).

One Health Knowledge of Toxoplasmosis

The majority (61.5%) of the participants knew about One Health, and 14% had no knowledge about One Health. Approximately 60.3% of participants knew about zoonosis, 26.5% were not aware of zoonosis, and 13.2% of participants were not sure about the concept of zoonosis. Out of 400 participants, 232 (58%) knew that toxoplasmosis is a zoonotic infection, and 18 participants (4.5%) had no knowledge on this. Only 8.8% of participants reported that toxoplasmosis was present in humans, 11% people reported that toxoplasmosis was present in livestock, 62.7% reported that toxoplasmosis was present in both humans and livestock, while 17.5% were not sure about this. Among the participants, 37.3% thought that toxoplasmosis causes blindness, 23.2% thought that toxoplasmosis did not cause blindness, and 39.5% were not sure about this (Table 6).

Association Among Different Variables Based on ANOVA

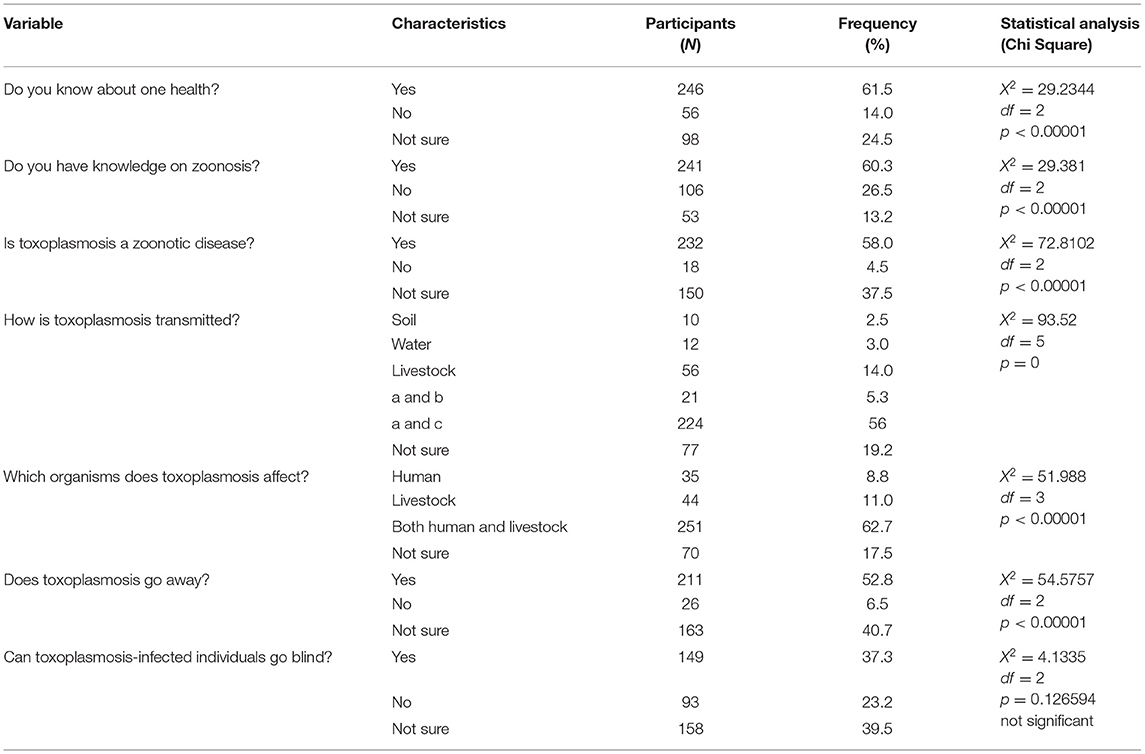

We used one-way ANOVA to determine whether there were any statistically significant differences among the means of three or more independent groups. We used six specific independent variables, i.e., age, sex, ethnicity, education, religion, and marital status, and five dependent variables, i.e., knowledge, attitudes, practices, risk factors, and One Health. Our ANOVA results revealed that age was associated (p < 0.05) with attitudes and One Health; however, there were no significant associations with sex. Ethnicity was associated (p < 0.05) with knowledge and One Health; religion was associated (p < 0.05) with One health; and marital status was associated (p < 0.05) with knowledge, attitudes, risk factors, and One health. Likewise, the education of the participants was associated (p < 0.05) with knowledge, risk factors, and One Health (Table 7).

Table 7. Association between demographic characteristics and knowledge, attitude, practices, one health, and risk factors (ANOVA).

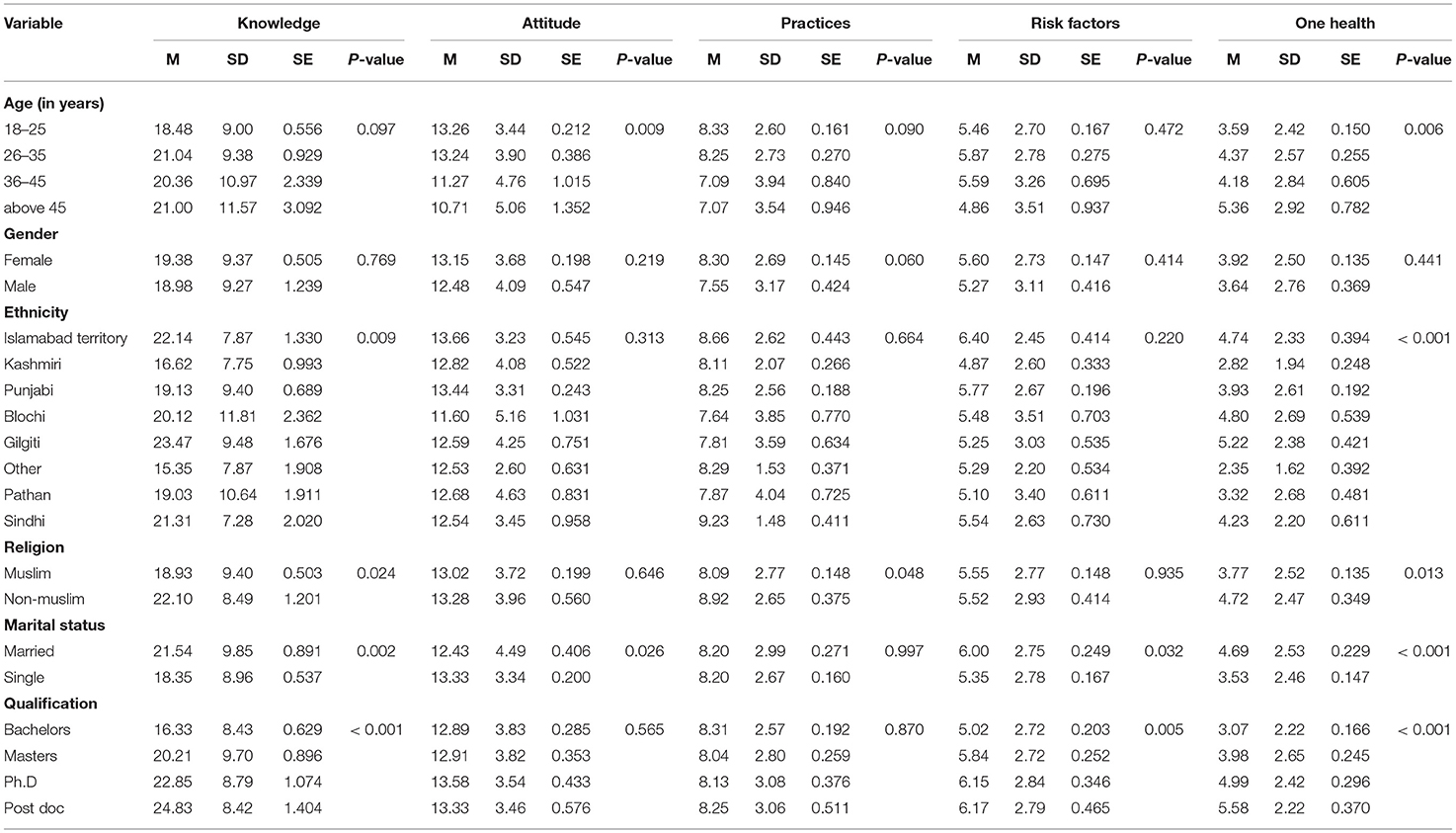

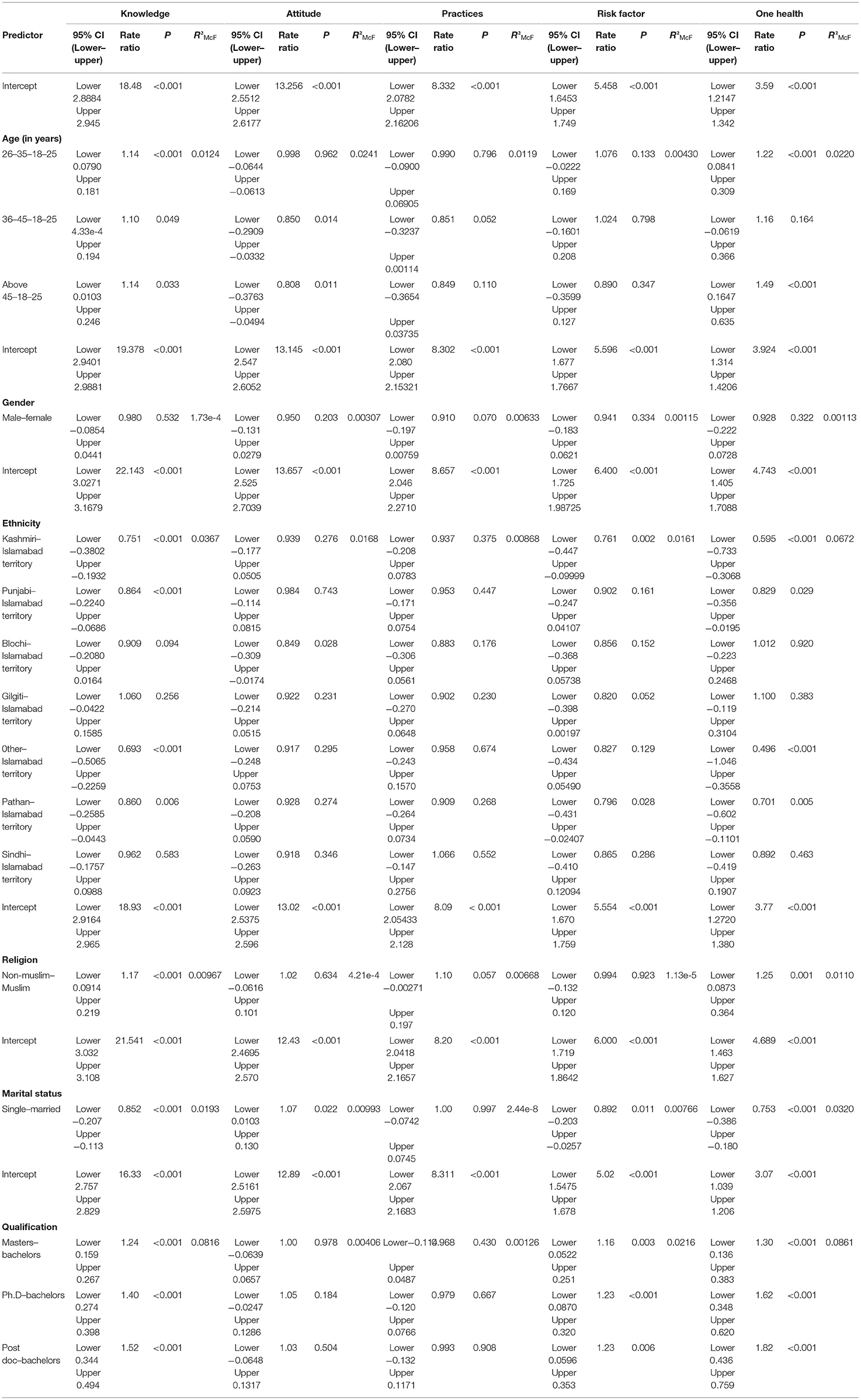

Statistical Analysis Using Log-Linear Regression

Log-linear regression analysis involves using a dependent variable measured by frequency counts with categorical or continuous independent predictor variable. Log-linear analysis is a technique used in statistics to examine the relationship between more than two categorical variables. The technique is used for both hypothesis testing and model building. In this study, we used the independent variables age, gender, ethnicity, education, religion, and marital status and the dependent variables knowledge, attitudes, practices, risk factors, and One Health. We applied log-linear regression on age and the dependent variables and obtained different p-values, rate ratios, and R2McF. Mostly high R2McF values represent goodness of fit. With the dependent variable knowledge, we obtained p < 0.001, a rate ratio of 18.48, and an R2McF value of 0.0124. With attitude as the dependent variable, we obtained p < 0.001, a rate ratio of 13.256, and an R2McF value of 0.0241. With the dependent variable practices, we obtained p < 0.001, a rate ratio of 8.332, and an R2McF value 0.0119. With risk factors, we obtained p < 0.001, a rate ratio of 5.458, and an R2McF value of 0.00430. Finally, with One Health, we obtained p < 0.001, a rate ratio of 3.59, and an R2McF value of 0.0220. The highest and lowest R2McF values were obtained for attitudes and risk factors, respectively.

We applied a log-linear regression on the independent variable gender and the dependent variables. With knowledge, we obtained p < 0.001, a rate ratio of 19.378, and an R2McF value of 1.73e-4. With attitudes, we obtained p < 0.001, a rate ratio of 13.145, and an R2McF value of 0.00307. With practices, we obtained p < 0.001, a rate ratio of 8.302, and an R2McF value of 0.00633. With risk factors, we obtained p < 0.001, a rate ratio of 5.596, and an R2McF value of 0.00115. With One Health, we obtained p < 0.001, a rate ratio of 3.924, and an R2McF value of 0.00113. The highest and lowest R2McF values were obtained for knowledge and One Health, respectively.

We applied log-linear regression on the independent variable ethnicity and the dependent variables. With knowledge, we obtained p < 0.001, a rate ratio of 22.143, and an R2McF value of 0.0367. With attitudes, we obtained p < 0.001, a rate ratio of 13.657, and an R2McF value of 0.0168. With practices, we obtained p < 0.001, a rate ratio of 8.657, and an R2McF value of 0.00868. With risk factors, we obtained p < 0.001, a rate ratio of 6.400, and an R2McF value of 0.0161. With One Health, we obtained p < 0.001, a rate ratio of 4.743, and an R2McF value of 0.0672. The highest and lowest R2McF values were for One Health and practices, respectively (Table 8).

Table 8. Association between demographic characteristics and knowledge, attitudes, practices, one health, and risk factors (log-linear regression).

Discussion

Toxoplasmosis is a major global zoonotic disease that has a deleterious effect on human health, with severe consequences in immunocompromised, pregnant women (10). Consumption of contaminated raw meat, water, fruits, and vegetables; contact with cats; and exposure to soil contaminated with cat feces are the main transmission routes (11). Out of 400 participants, 240 (60%) were aware of toxoplasmosis. Similar findings have been reported in Northeast Ethiopia (1).

Our study findings revealed that 87.3 and 85.5% of participants washed their hands after gardening and changing the cat litter, respectively. Additionally, 89% of participants thoroughly cooked meat prior to consumption, and 86.3% avoided drinking raw milk. A study from Ethiopia reported that among pregnant women, 77.6% washed their hands after gardening, 64.7% washed their hands after changing the cat litter, and 62.2% washed their hands after handling raw meat. Furthermore, 85.9% of the pregnant women reported that they did not avoid drinking untreated water (1). In our study, 80% of participants considered toxoplasmosis to be a dangerous disease, and 33.5% reported that they had not consumed undercooked meat. In contrast, a study reported that 51.4% of participants did not consider toxoplasmosis to be a severe disease. Additionally, 48% individuals were unsure whether toxoplasmosis was spread via consumption of inadequately washed vegetables (30). Our study showed that 81.8% of participants washed their kitchen utensils after contact with raw meat or unwashed fruits and vegetables. Similar findings were obtained in Brazil, where 24.7% of pregnant women reported washing kitchen utensils (31). Approximately 30% of the participants did not allow anyone else to change the cat litter box. Similar findings have been reported in a study conducted in Northeast Ethiopia where 51.3% women responded that they did not allow someone else to change the cat litter box (1).

Most of the participants (76.8%) reported that toxoplasmosis was acquired by consuming raw/undercooked meat. These findings were consistent with those of a study carried out in Mexico, where more than half of the respondents correctly defined the routes of transmission: (1) consumption of raw or undercooked foods, unwashed fruits and vegetables and (2) direct contact with cats (32). In our study, 69.5% of participants considered blood transfusion to be a cause of toxoplasmosis. In one of the surveys, 27.7% of the participants did not assume that blood transfusion could spread toxoplasmosis, and 38.5% believed that it could be transmitted from the mother to her fetus (33). Approximately 68.3% of participants responded that gardening without gloves could be a transmission source of toxoplasmosis. In a study conducted in the US, 29% of the participants thought that toxoplasmosis could be transmitted by gardening without gloves (34). Our study findings showed that immunocompromised pregnant women had a high risk of toxoplasmosis similar to the findings of Desta who reported there is a high risk of toxoplasmosis in immunocompromised, pregnant women (77.9%) (1). The majority (58%) of participants reported that toxoplasmosis is a zoonotic infection. A previous study reported that 33.82% of participants were aware that toxoplasmosis is a zoonotic disease (1).

Strength, Limitations, and Future Recommendations

The limited amount of knowledge about toxoplasmosis emphasized to provide and promote health education regarding toxoplasmosis especially awareness regarding transmission of disease in the pregnant women. It is important to improve primary health care system of the country for the better control, management, and prevention of the disease. Moreover, it is stressed that in the study population to commence health education and awareness campaigns for the community and to design relevant policies for the guidance of the government and stakeholders to reduce the risk of disease. In the study design, the use of close questionnaire is one of the limitation, where free form response was not allowed. In our study included the participants from university which is not representative of the situation of whole country. The strength of the study is maximum number of female participants and preliminary study on the knowledge about toxoplasmosis among university students in Pakistan.

Materials and Methods

Study Area

We conducted a cross-sectional analysis in Islamabad and Rawalpindi district of Punjab, Pakistan, also known as twin cities. The terrain consists of plains and mountains in the metropolitan area of Islamabad and Rawalpindi. In the mountainous terrain of Margala hills is the northern part of the metropolitan area, while Rawalpindi is situated on the Pothohar plateau (35).

Participants

The study participants included students from universities of the twin cities that were enrolled in different degree programs (Bachelors, Masters, Ph.D., and Post doc). The sample size was calculated using Raosoft software (http://www.raosoft.com/samplesize.html; 5% margin of error, 95% confidence level, and 50% response distribution). Four hundred questionnaires were randomly distributed and filled by the participants. We collected data from July through December 2020.

Sample Size

A questionnaire was designed to access the knowledge, attitude, practices, risk factor and one health regarding toxoplasmosis. A total of 400 questionnaires were administrated. The questionnaire was categories into the following sections as demography (n = 17), knowledge (n = 34), attitude (n = 19), practices (n = 11), risk factors (n = 8), and one health (n = 7).

Data Collection

We developed a structured questionnaire to collect the data. After obtaining verbal informed consent from the participants, we conducted interviews. A team was trained for interviews, data collection, and record keeping. A supervisor routinely coordinated the interview process to ensure adequate data collection and record maintenance. The purpose of study was explained to the participants. The questionnaire consisted of six sections. The first section was on the socio-demographics of the participants. The second section was on the knowledge on toxoplasmosis, including common signs, symptoms, and diagnostic tests used for toxoplasmosis. The third section was on the attitudes and perceptions toward toxoplasmosis. The fourth section was on practices performed when toxoplasmosis was either suspected or diagnosed. The fifth section was on major risk factors of the disease, and the sixth section was on One Health questions regarding toxoplasmosis.

Statistical Analysis

We generated a database using Excel (Microsoft, Redmond, WA, USA) and calculated basic frequencies. We used descriptive statistics to initially analyze the data and classified the variables into independent and dependent variables. We performed statistical analysis using Jamovi software (version 1.6.7; https://www.jamovi.org) to observe the factors involved in the occurrence of toxoplasmosis. The relationship between various factors influencing knowledge, attitudes, and practices was analyzed. For data analysis, we used Chi square test, one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), and log-linear regression.

Conclusions

There is a low level of knowledge and awareness regarding toxoplasmosis among males. Therefore, there should be awareness programs to educate individuals about the risks of this deadly disease and to provide information on the major routes of transmission. Our study highlights the need of toxoplasmosis awareness to reduce the burden and economic impact of the disease.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author/s.

Ethics Statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by the Ethics Committee of COMSATS University. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author Contributions

HA and KS designed and supervised the study. TM and KS performed the data collection. KS, SS, SA, MA, HA, and JC conducted statistical and data analysis. SN drafted the manuscript. SS and JC performed critical revisions. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by the Fifth Round of Three-Year Public Health Action Plan of Shanghai (Grant No. GWV-10.1-XK13 to JC), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant Nos. 81772225 and 81971969 to JC), and the Key Laboratory of Parasite and Vector Biology, National Health Commission of People's Republic of China (Grant No. WSBKFKT2017-01). The funders had no role in the study design, the data collection and analysis, the decision to publish, or the preparation of the manuscript.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Acknowledgments

The authors are thankful to Kaleem Imdad and Naseer Shah for their assistance during the preparation of this manuscript.

Abbreviations

WHO, World Health Organization; NZDs, Neglected Zoonotic Diseases; T. gondii, Toxolasma gondii; DALYs, Disability Adjusted Life Years.

References

1. Desta AH. Knowledge, attitude and practice of community towards zoonotic importance of toxoplasma infection in central Afar Region, North East Ethiopia. Int J Biomed Sci Eng. (2015) 3:74–81. doi: 10.11648/j.ijbse.20150306.12

2. Saadatnia G, Golkar M. A review on human toxoplasmosis. Scand J Infect Dis. (2012) 44:805–14. doi: 10.3109/00365548.2012.693197

3. Tavalla M, Oormazdi H, Akhlaghi L, Shojaee S, Razmjou E, Hadighi R, et al. Genotyping of toxoplasma gondii isolates from soil samples in Tehran, Iran. Iran J Parasitol. (2013) 8:227–33.

4. Stillwaggon E, Carrier CS, Sautter M, McLeod R. Maternal serologic screening to prevent congenital toxoplasmosis: a decision-analytic economic model. PLoS Neglect Trop Dis. (2011) 5:e1333. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0001333

5. Robert-Gangneux F, Dardé ML. Epidemiology of and diagnostic strategies for toxoplasmosis. Clin Microbiol Rev. (2012) 25:264–96. doi: 10.1128/CMR.05013-11

6. Tasawar Z, Aziz F, Lashar MH, Shafi S, Ahmad M, Lal V, et al. Seroprevalence of human toxoplasmosis in southern Punjab, Pakistan. Pak J Life Soc Sci. (2012) 10:48–52.

7. Rehman F, Shah M, Ali A, Rapisarda AMC, Cianci A. Seroprevalence and risk factors of toxoplasma gondii infection in women with recurrent fetal loss from the province of khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Pakistan. J Neonatal Perinatal Med. (2020) 14:115–21. doi: 10.3233/NPM-190323

8. Pomares C, Ajzenberg D, Bornard L, Bernardin G, Hasseine L, Dardé ML, et al. Toxoplasmosis and horse meat, France. Emerg Infect Dis. (2011) 17:1327–8. doi: 10.3201/eid1707.101642

9. CDC. MMWR Recommendations and Reports. (2000). Available online at: https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/rr4902a5.htm#:~:text=Etiologic%20Factors%3A%20Toxoplasma%20can%20be,exposure%20to%20cat%20litter%20or (accessed February 9, 2021)

10. Hampton MM. Congenital toxoplasmosis: a review. Neonatal Netw. (2015) 34:274–8. doi: 10.1891/0730-0832.34.5.274

11. Furtado JM, Smith JR, Belfort R, Gattey D, Winthrop KL. Toxoplasmosis: a global threat. J Glob Infect Dis. (2011) 3:281–4. doi: 10.4103/0974-777X.83536

12. Antczak M, Dzitko K, Długońska H. Human toxoplasmosis–Searching for novel chemotherapeutics. Biomed Pharmacother. (2016) 82:677–84. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2016.05.041

13. Delair E, Monnet D, Grabar S, Dupouy-Camet J, Yera H, Brézin AP. Respective roles of acquired and congenital infections in presumed ocular toxoplasmosis. Am J Ophthalmol. (2008) 146:851–5. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2008.06.027

14. Liu Q, Wang ZD, Huang SY, Zhu XQ. Diagnosis of toxoplasmosis and typing of Toxoplasma gondii. Parasites Vect. (2015) 8:292. doi: 10.1186/s13071-015-0902-6

15. da Silva PD, Shiraishi CS, da Silva AV, Gonçalves GF, Sant'Ana DD, de Almeida Araújo EJ. Toxoplasma gondii: a morphometric analysis of the wall and epithelial cells of pigs intestine. Exp Parasitol. (2010) 125:380–3. doi: 10.1016/j.exppara.2010.03.004

16. Dubey JP, Darrington C, Tiao N, Ferreira LR, Choudhary S, Molla B, et al. Isolation of viable Toxoplasma gondii from tissues and feces of cats from Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. J Parasitol. (2013) 99:56–8. doi: 10.1645/GE-3229.1

17. Ashburn D, Chatterton JMW, Evans R, Joss AWL, Ho-Yen DO. Success in the toxoplasma dye test. J Infect. (2001) 42:16–9. doi: 10.1053/jinf.2000.0764

18. Zhu C, Cui L, Zhang L. Comparison of a commercial ELISA with the modified agglutination test for detection of Toxoplasma gondii antibodies in sera of naturally infected dogs and cats. Iran J Parasitol. (2012) 7:89–95.

19. Oncel T, Vural G, Babür C, Kiliç S. Detection of Toxoplasmosis gondii seropositivity in sheep in yalova by sabin feldman dye test and latex agglutination test. Turkish J Parasitol. (2005) 29:10–2.

20. Webster JP, Dubey JP. Toxoplasmosis of animals and humans. Parasites Vect. (2010) 3:112. doi: 10.1186/1756-3305-3-112

21. Sucilathangam G, Palaniappan N, Sreekumar C, Anna T. IgG - indirect fluorescent antibody technique to detect seroprevalence of Toxoplasma gondii in immunocompetent and immunodeficient patients in southern districts of Tamil Nadu. Indian J Med Microbiol. (2010) 28:354–7. doi: 10.4103/0255-0857.71835

22. Wang Z, Ge W, Li J, Song M, Sun H, Wei F, et al. Production and evaluation of recombinant granule antigen protein GRA7 for serodiagnosis of Toxoplasma gondii infection in cattle. Foodborne Pathog Dis. (2014) 11:734–9. doi: 10.1089/fpd.2014.1749

23. Remington JS, Eimstad WM, Araujo FG. Detection of immunoglobulin M antibodies with antigen-tagged latex particles in an immunosorbent assay. J Clin Microbiol. (1983) 17:939–41. doi: 10.1128/jcm.17.5.939-941.1983

24. Terkawi MA, Kameyama K, Rasul NH, Xuan X, Nishikawa Y. Development of an immunochromatographic assay based on dense granule protein 7 for serological detection of toxoplasma gondii infection. Clin Vac Immunol. (2013) 20:596–601. doi: 10.1128/CVI.00747-12

25. Wang H, Lei C, Li J, Wu Z, Shen G, Yu R. A piezoelectric immunoagglutination assay for Toxoplasma gondii antibodies using gold nanoparticles. Biosens Bioelectro. (2004) 19:701–9. doi: 10.1016/S0956-5663(03)00265-3

26. Stroehle A, Schmidt K, Heinzer I, Naguleswaran A, Hemphill A. Performance of a western immunoblot assay to detect specific anti-Toxoplasma gondii IgG antibodies in human saliva. J Parasitol. (2005) 91:561–3. doi: 10.1645/GE-423R

27. Bonyadi MR, Bastani P. Modification and evaluation of avidity IgG testing for differentiating of Toxoplasma gondii infection in early stage of pregnancy. Cell J. (2013) 15:238–43.

28. Ahmed H, Malik A, Mustafa I, Arshad M, Khan MR, Afzal S, et al. Seroprevalence and spatial distribution of toxoplasmosis in sheep and goats in north-eastern region of Pakistan. Korean J Parasitol. (2016) 54:439–46. doi: 10.3347/kjp.2016.54.4.439

29. Nazir F, Khan MA. Trends in Milk Production Through Community Participation. Lahore: The Nation (2009).

30. Mahfouz MS, Elmahdy M, Bahri A, Mobarki YM, Altalhi AA, Barkat NA, et al. Knowledge and attitude regarding toxoplasmosis among Jazan University female students. Saudi J Med Sci. (2019) 7:28. doi: 10.4103/sjmms.sjmms_33_17

31. Moura IPDS, Ferreira IP, Pontes AN, Bichara CNC. Toxoplasmosis knowledge and reventive behavior among pregnant women in the city of Imperatriz, Maranhão, Brazil. Ciência Saúde Coletiva. (2019) 24:3933–46. doi: 10.1590/1413-812320182410.21702017

32. Laboudi M, Ait Hamou S, Mansour I, Hilmi I, Sadak A. The first report of the evaluation of the knowledge regarding toxoplasmosis among health professionals in public health centers in Rabat, Morocco. Trop Med Health. (2020) 48:1–8. doi: 10.1186/s41182-020-00208-9

33. Senosy SA. Knowledge and attitudes about toxoplasmosis among female university students in Egypt. Int J Adolesc Med Health. (2020). doi: 10.1515/ijamh-2019-0207

34. Kravetz JD, Federman DG. Toxoplasmosis in pregnancy. Am J Med. (2005) 118:212–6. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2004.08.023

Keywords: knowledge, attitude, practices, risk factor, one health, toxoplasmosis, Pakistan

Citation: Maqsood T, Shahzad K, Naz S, Simsek S, Afzal MS, Ali S, Ahmed H and Cao J (2021) A Cross-Sectional Study on the Association Between Risk Factors of Toxoplasmosis and One Health Knowledge in Pakistan. Front. Vet. Sci. 8:751130. doi: 10.3389/fvets.2021.751130

Received: 31 July 2021; Accepted: 26 October 2021;

Published: 18 November 2021.

Edited by:

Si-Yang Huang, Yangzhou University, ChinaReviewed by:

Wei Cong, Shandong University, ChinaZedong Wang, First Hospital of Jilin University, China

Copyright © 2021 Maqsood, Shahzad, Naz, Simsek, Afzal, Ali, Ahmed and Cao. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Haroon Ahmed, haroonahmad12@yahoo.com; Jianping Cao, caojp@yahoo.com

Tooba Maqsood1

Tooba Maqsood1  Khuram Shahzad

Khuram Shahzad Shumaila Naz

Shumaila Naz Sami Simsek

Sami Simsek Muhammad Sohail Afzal

Muhammad Sohail Afzal Shahzad Ali

Shahzad Ali Haroon Ahmed

Haroon Ahmed Jianping Cao

Jianping Cao