Advancing early relational health: a collaborative exploration of a research agenda

- 1Division of Child and Adolescent Health, Department of Pediatrics, Columbia University Vagelos College of Physicians and Surgeons and NewYork-Presbyterian Morgan Stanley Children’s Hospital, New York, NY, United States

- 2Division of Developmental Neuroscience, Department of Psychiatry, Columbia Vagelos College of Physicians and Surgeons, New York, NY, United States

- 3Department of Psychiatry, The University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI, United States

- 4Department of Human Development and Family Science, Auburn University, Auburn, AL, United States

- 5Science and Innovation Strategy, Institute for Child Success, Greenville, SC, United States

- 6Department of Pediatrics, Division of General Pediatrics and Adolescent Health, Duke University School of Medicine, Durham, NC, United States

- 7Vav Amani Consulting LLC, El Cerrito, CA, United States

- 8HealthySteps, ZERO TO THREE, Washington, DC, United States

- 9Center for Child and Human Development, Georgetown University, Washington, DC, United States

- 10Fortune Consulting, Early Relational Health-Family Network Collaborative, Royal Oak, MI, United States

- 11Department of Research and Innovation, Reach out and Read, Boston, MA, United States

- 12Chief Executive Officer, Reach Out and Read, Boston, MA, United States

- 13Department of Pediatrics, Rutgers Robert Wood Johnson Medical School, Piscataway, NJ, United States

- 14Department of Pediatrics, Division of General Pediatrics, Stanford University School of Medicine, Stanford, CA, United States

- 15Center for the Study of Social Policy, Washington, DC, United States.

Here, we introduce the Early Relational Health (ERH) Learning Community's bold, large-scale, collaborative, data-driven and practice-informed research agenda focused on furthering our mechanistic understanding of ERH and identifying feasible and effective practices for making ERH promotion a routine and integrated component of pediatric primary care. The ERH Learning Community, formed by a team of parent/caregiver leaders, pediatric care clinicians, researchers, and early childhood development specialists, is a workgroup of Nurture Connection—a hub geared toward promoting ERH, i.e., the positive and nurturing relationship between young children and their parent(s)/caregiver(s), in families and communities nationwide. In response to the current child mental health crisis and the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) policy statement promoting ERH, the ERH Learning Community held an in-person meeting at the AAP national headquarters in December 2022 where members collaboratively designed an integrated research agenda to advance ERH. This agenda weaves together community partners, clinicians, and academics, melding the principles of participatory engagement and human-centered design, such as early engagement, co-design, iterative feedback, and cultural humility. Here, we present gaps in the ERH literature that prompted this initiative and the co-design activity that led to this novel and iterative community-focused research agenda, with parents/caregivers at the core, and in close collaboration with pediatric clinicians for real-world promotion of ERH in the pediatric primary care setting.

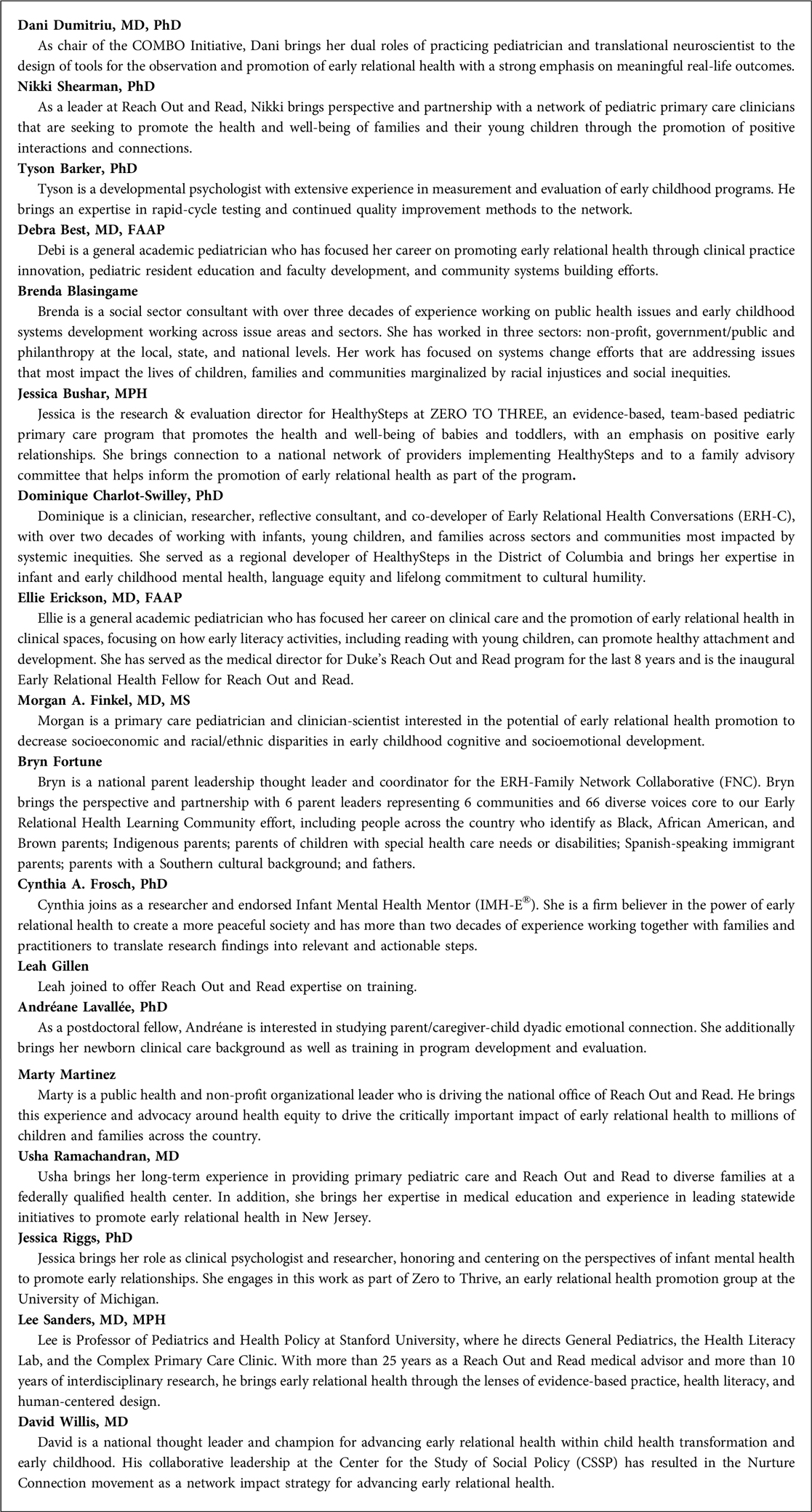

Introduction

Prompted by the intersection of widespread recognition of a child mental health crisis and a 2021 American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) policy statement proposing the promotion of early relational health (ERH) as a strength-based prevention strategy, a team of parent/caregiver leaders, pediatric care clinicians, researchers, and early childhood development specialists was convened in 2022 to bring diverse perspectives to thinking critically and innovatively about best practices and public health policies that advance ERH. This consortium, named the ERH Learning Community, is a workgroup of Nurture Connection (1), a recently launched hub building a national movement to promote ERH defined as the state of emotional well-being that stems from the early positive and mutually nurturing relational bonds between children and their parent(s)/caregiver(s) (1). Invited through an intentional and inclusive process by the instigators of the Learning Community, members were chosen to ensure diverse representation of end users and experts in practice and different research methodologies. The characteristics and contribution of each member are described in Box 1. In December 2022, following five monthly online meetings, the ERH Learning Community gathered for an inaugural 2-day in-person meeting at the AAP national headquarters. No predetermined agenda on specific strategies to be advanced within the ERH realm was set prior to the meeting. Rather, we sought the emergence of consensus through a co-design activity. Here, we summarize the critical problem that brought us together, the solution proposed by the AAP, the gaps in current evidence to actuate this solution, and our proposed co-designed integrated research agenda that emerged from this meeting. We outline a bold, large-scale, collaborative, community-focused, data-driven investigation of the eco-bio-developmental mechanisms (2) associated with ERH, combined with practice-informed research to test real-world feasibility, acceptability, effectiveness, scalability, and impact of light-touch interventions within pediatric primary care aimed at maximizing the power of ERH at supporting wellness and health in families and communities.

Contemporary crises: child mental health and loneliness

The most prominent organizations in children's mental health have declared a national emergency due to the sharp rise in pediatric mental health disorders (3). The critical nature of the situation was first highlighted in 2020 (4) and reiterated in 2022 (5) by the AAP, the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry (AACAP) and the Children's Hospital Association (CHA), who joined efforts to tackle the continued rising number of children struggling with mental health disorders across the nation. The February 2022 Center for Disease Control and Prevention Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report estimated that mental health disorders affect as many as 40% of all children (6). Associated with the child mental health crisis, U.S. Surgeon General Dr. Vivek Murthy officially declared in 2023 an epidemic of loneliness, raising awareness about the long-lasting damaging impacts of social disconnection (7). Human social connection is a complex phenomenon shaped by the structure, functions and quality of relationships (8) stemming from the early-life experiences in the parenting/caregiving environment (9). These national emergencies call for urgent public health research and action to identify and implement effective strategies that strengthen family and community connectedness and promote life-course health and well-being, even in the presence of mental health disorders (10, 11).

A Major driver of the child mental health crisis: childhood adversity

There is strong evidence that exposure to childhood adversity conveys risk for poor mental and physical health outcomes across the life-course (12–22) and profoundly impacts overall child well-being. The original Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) Study assessed seven specific adverse experiences: psychological, physical, or sexual abuse; violence against mother; and living with household members with substance abuse, mental illness/suicidality, or ever imprisoned (23). Addressing a limitation of the original ACE study that was conducted with White, middle-class individuals, further research including more diverse populations expanded the list of ACEs to better represent common experiences (24).

Critically, during discussions following our in-person meeting, the ERH Learning Community recognized post-pandemic trends of spiking poverty and food insecurity (25), parent/caregiver psychopathology (26–35), child maltreatment (36) and neglect (33), breaks in provision of protective services (37), family and domestic violence (38–42), racism (43, 44), parental/caregiver loss (45), social isolation (46) and loneliness (47). Situated in this context, we refer to childhood adversity as an inclusive term that encompasses adverse community environments (e.g., poverty, racism, cyberbullying), and family-level and contextual stressors (48) (e.g., parent/caregiver psychopathology, domestic violence, neglect). This centering of both individual and community experiences to be “representative of America” is an important driver toward our emergent research agenda. We recognize that what works for whom, under what conditions, and toward what benefit, might not be universal. Thus, an inclusive and equitable investigation of the promotion of ERH must be designed to identify the specific needs and, even more importantly, the diverse strengths of different communities.

A proposed buffer: early relational health

ERH encompasses diverse theoretical constructs including bonding, sensitivity, attachment, and emotional connection, that ultimately converge in their shared objective of describing distinct facets of the parent/caregiver-child relationship. Decades of accumulating evidence points to ERH playing a fundamental role in child physical health, cognitive and socioemotional development, and well-being (49, 50). ERH is also thought to protect against the negative effects of childhood adversity (14, 23, 51–53).

Given the far-reaching implications of strong ERH for child mental health and development (49, 52–54), the AAP published a policy statement in 2021 reorienting pediatric care toward an emphasis on ERH as a promoter of health and well-being across the lifespan (51, 52). Strength-based promotion of healthy early relationships is proposed as a support for families during the current mental health crisis by buffering against childhood adversity, leading to improved health, sense of competence, connection and well-being of both children and their parents/caregivers.

The AAP policy statement also emphasized the importance of developing strategies that focus on early childhood, and the opportunity offered by the pediatric primary care setting for promoting ERH. The first 1,000 days of an infant's life are a critical period for promoting positive and mutually nurturing parent/caregiver-child relationships (11) owing to developmental embedding that has the potential to affect long-term health and well-being. In the face of adversity, a study of 3,500 children showed that the quality of ERH in infancy mattered more than the severity of perinatal adversity in predicting later functioning (55). Pediatric primary care offers standardized, pre-established, consistent, accessible and affordable care in the first few years of a child's life (54–56). It occupies the privileged position of having widespread access to infants, with an estimated well-child visit attendance rate of 63%–93% in the first 3 years of life, even in low income families (57). In commercially insured children, preventative primary care visits increased by 9.9% from 2009 to 2016 (58). Pediatric primary care is delivered in different settings, including within family-centered medical homes where pediatricians are expertly prepared to handle child health needs by providing continuous, affordable, compassionate care with cultural humility (56). Other settings include group well-child care which is thought to increase equitable health care delivery (59) with many documented health benefits for families experiencing marginalization and underserved communities. Benefits include increased adherence to well-child visits, better child nutritional behaviors, increased rates of breastfeeding, optimal child health status and development, and increased parental social support, caregiving behaviors, self-efficacy and psychological well-being (60). Pediatric primary care is thus an ideal setting for widespread implementation of time-efficient and cost-effective strategies focused on promoting ERH (51, 61).

Identified gaps in promoting ERH: knowledge meets real-world

Prior to our in-person meeting, several of the ERH Learning Community members (AL, MF, DW, NS, DD) contributed to a systematic review and meta-analysis that assessed the global effectiveness of contemporary parent/caregiver-child interventions, initiated within the first six months of life, specifically aimed at improving ERH (62). Consistent with other reviews, we confirmed the effectiveness of the identified interventions in improving a heterogenous set of ERH outcomes including maternal bonding, child attachment, parent/caregiver-child emotional connection, and parent/caregiver emotional availability. However, effect sizes were mostly small-to-moderate and time-limited, with most of the significant effects observed immediately after the intervention ended, and very few studies investigating long-term effects past a few months to years out.

Importantly, our meta-analysis did not provide significant evidence from real-world contexts to support the abundant body of work establishing an association between ERH and later child emotional, mental, and physical health (63–68). These results do not necessarily reflect a lack of causal effect between improved ERH and later child outcomes, but rather underscore the need for additional investigation into the processes and mechanisms underlying the relationship between ERH and life-course health and well-being, as well as exploring the real-world conditions that influence the effectiveness of interventions.

Another identified gap in our systematic review was that only 3 (69–71) of the 93 interventions were implemented by pediatricians or in family-centered pediatric medical homes. Yet it is widely recognized, including in the AAP policy statement, that leveraging pediatric primary care for universal promotion of ERH holds significant potential to yield public health benefits (51).

Additionally, 95% of identified studies focused on biological mothers and only 8% targeted a population at-large rather than focusing on groups with specific risk-factors, pointing to potential lack of generalizability of results to a more inclusive view of families and communities. Finally, we note that no study to-date has included a comprehensive battery of all constructs within the ERH literature (i.e., bonding, attachment, emotional connection, repair, etc.), but rather focus on one or a few of these constructs, limiting the interpretability of which interventions improve which specific ERH constructs. We view these gaps as opportunities that pave the road to a comprehensive research agenda that expands our understanding of underlying mechanisms underpinning the emergence and maintenance of ERH, and uses this knowledge to simultaneously develop and refine effective, equitable, evidence-based ERH interventions. Favorably, our systematic review also found that relational interventions improve ERH outcomes non-dose-dependently, supporting the possibility for scalable light-touch interventions.

A Co-design activity: emerging vision for a research agenda

To increase the validity of the ERH Learning Community in-person meeting's outcome, no predetermined agenda for the “what” and “how” to usher in best practices in ERH promotion was set prior to our in-person gathering. Rather, the goal was to co-design iteratively and collaboratively an agenda that will lead to an evidence-based framework for effective and equitable promotion of ERH.

Our initial discussion was centered around a vision that advancing ERH can improve life-course health and well-being by improving social cohesiveness and belonging and repair within families and communities. With reference to this vision, we engaged in a co-design process to define a focused problem statement and to identify real-world solutions. Specifically, all members were presented with two sets of prompts, to which they offered independent responses written on sticky notes and placed on four sections of a board. The prompts were: “If we succeed, in 10 years, 1a-What will be the news headline? and 1b-What will families, medical clinicians, and other involved groups post/tweet about it?”; “2a-What do we want to solve (what/where/how/for whom/when)? And 2b-How do we want to solve it?” After responses were posted (n = 113), the group discussed convergent and divergent views.

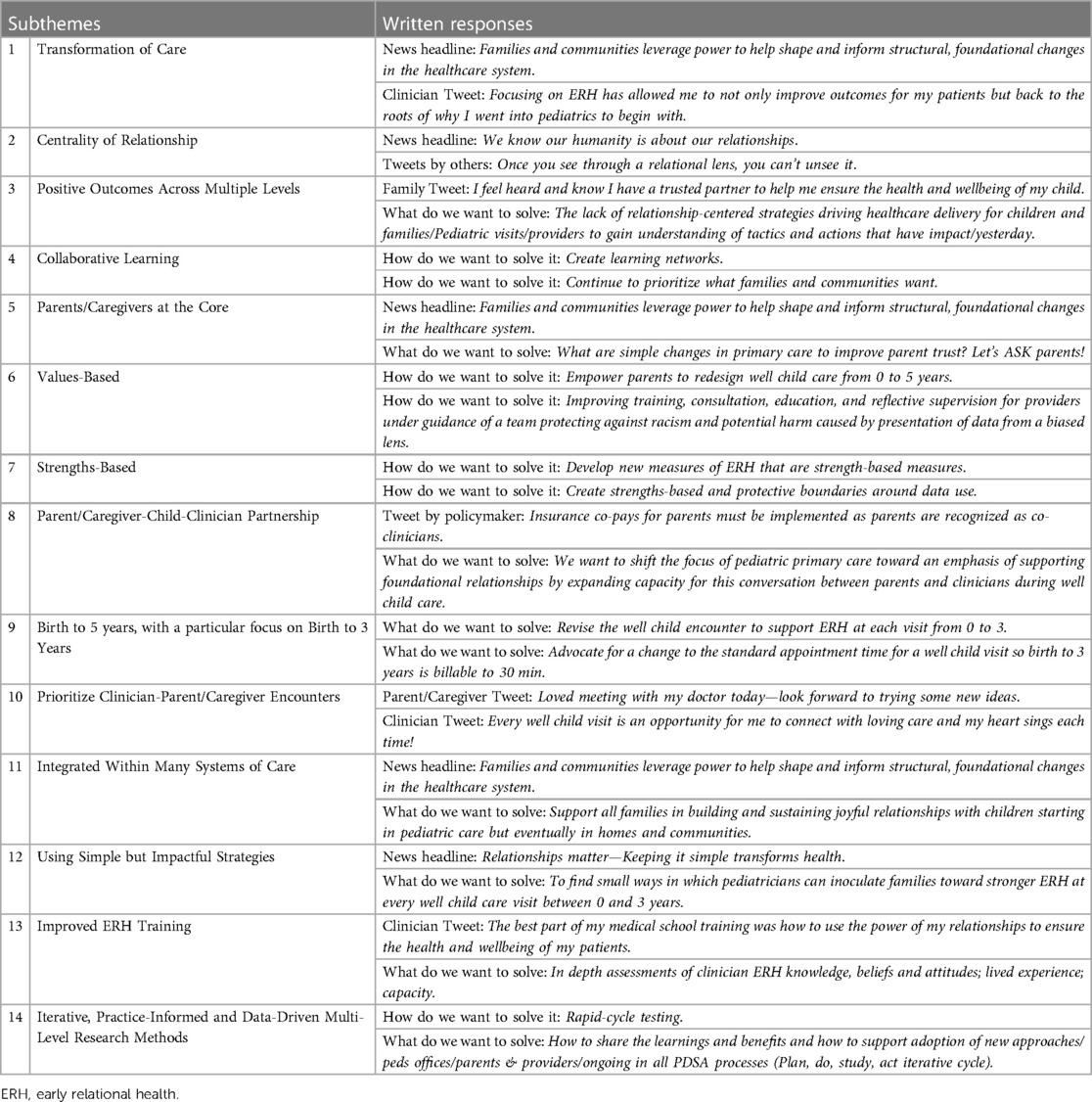

Following the meeting, we applied a human-centered design process (72) to identify prominent themes from the text data (i.e., written responses). Using an inductive approach inspired by thematic analysis, three members of the ERH Learning Community (AL, LG, NS) independently coded the responses for themes and subthemes. Engaging members with firsthand knowledge of the data collection context from the in-person meeting was in line with a human-centered approach, preserving contextual insight, participant perspectives, and the credibility of the outcomes. To increase objectivity, in a confirmation phase, two additional members (JR, CF), one of whom had not attended the in-person meeting and was therefore blinded to the prompts and subsequent conversation (CF), reviewed the data and codes to refine the themes and subthemes to avoid conceptual overlap. Percent agreement between coders in the confirmatory phase ranged from 83.2% to 98.2%. Finally, in a member checking phase (73), themes and subthemes were summarized, presented, reviewed and validated by the ERH Learning Community members. This comprehensive process took place during a follow-up virtual meeting held in February 2023, where 10 members who had attended the in-person meeting provided feedback to ensure the accuracy and credibility of the findings. Given the human-centered design approach, researchers' involvement in the analysis process was deemed fitting to most accurately capture the group's collective vision of the research agenda; however, recognizing the potential for bias, the validation and member checking phase was incorporated to enhance rigor and mitigate subjectivity. In total, 14 subthemes were identified across 3 themes: 1-Goals of the Learning Community agenda; 2-Processes underpinning the agenda; and 3-Strategies to execute the agenda. Examples of direct quotes of written responses for each subtheme that represent the diverse voices in the room are provided in Table 1.

Theme 1: goals of the learning community agenda

Transformation of Care (subtheme 1) was the most prominent subtheme mentioned in 59 written responses. This subtheme translates the Community's goal of transforming and rethinking pediatric primary healthcare. Centering well-child visits on health, wellness, and strengths of the parent/caregiver-child relationship is at the core of this subtheme. Centrality of Relationships (subtheme 2) was mentioned in 36 written responses and encompasses the ERH Learning Community's acknowledgement that “relationships matter” and that pediatric care should strive to become relationship-centered. The importance of centering relationships bled into subtheme 3, which focuses the research agenda on Positive Outcomes Across Multiple Levels (n = 37). Congruent with the ERH literature, a research agenda centered around universal promotion of ERH needs to be outcome-focused, demonstrating improved objective measures of health and well-being. However, the ERH Learning Community also identified the need to measure more subjective outcomes, such as love, joy, empathy, strength, forgiveness, repair, etc., and the importance of measuring outcomes not only in children but also in families and communities. Additionally, adoption of a Collaborative Learning approach (subtheme 4; n = 9) emerged as a subtheme for participation of pediatric clinicians, parents/caregivers, scientists, and policymakers.

Theme 2: processes underpinning the agenda

Consistent with our collaborative learning approach, the importance of having Parents/Caregivers at the Core (subtheme 5) was present in 37 written responses. Parents/Caregivers partnering at every step with scientists and other collaborators as the research agenda is developed and carried out is critical. As this partnership unfolds, the ERH Learning Collaborative is adopting a Values-Based (subtheme 6; n = 23), as well as a Strengths-Based (subtheme 7; n = 5) approach. Principles of equity, diversity, representation, respect, and cultural humility (74) drive not only the relationships among members of the ERH Learning Community but also fundamentally influence how the research agenda will be strategized and implemented. Finally, another emerging subtheme underlying our processes is the focus on the Parent/Caregiver-Child-Clinician Partnership (subtheme 8; n = 18), building on trust, value, and collaboration to abolish the traditional hierarchical model.

Theme 3: strategies to execute the agenda

The third theme defined how the ERH Learning Community conceptualized the “who/when/where/how” to be targeted via a comprehensive research agenda. To promote ERH effectively, our work will center on parent/caregiver-child relationships from Birth to 5 Years, with a Particular Focus on Birth to 3 Years (subtheme 9; n = 13). Efforts will Prioritize Clinician-Parent/Caregiver Encounters (subtheme 10; n = 21) as opportunities for widespread foundational promotion of ERH, with recognition that our work must ultimately be Integrated Within Many Systems of Care (subtheme 11; n = 9), eventually extending beyond pediatrics to be inclusive of educational settings, home visiting, and other parent/caregiver-child facing contexts. Using Simple but Impactful Strategies (subtheme 12; n = 8) is also critical for feasibility and effectiveness. The “how” also included Improved ERH Training (subtheme 13; n = 8) for pediatric clinicians, and most importantly an Iterative, Practice-Informed and Data-Driven Multi-Level Research Approach (subtheme 14; n = 27), including new and improved measures of ERH.

The emerging themes define the ERH Learning Community's unified goals, core processes, and strategies, and guide the development of a multi-layered, iterative approach with emphasis on lived experiences and experiential learning leading to innovations.

Our proposed bold novel research approach

Expanding upon convergent areas of research (11, 12, 51, 52, 75–77), we propose a unique collaboration, inclusive of a broad array of partners with diverse perspectives, with the vision of establishing an evidence base that will drive policy and practice towards hardwiring ERH promotion into pediatric primary care. To rapidly move the needle, we propose a combination of data-driven and practice-informed research methodologies, with parents'/caregivers' and pediatric clinicians' perspectives at the core.

This research approach centers two goals: 1-generate foundational knowledge about ERH in early childhood and its life-course implications, and 2-identify the most feasible and effective practices for making ERH promotion a routine and integrated component of pediatric primary care. To achieve this, we believe it is necessary to connect an extensive network of clinics and clinicians as a platform for field research with a large-scale data-capture effort to acquire longitudinal and cross-sectional parent/caregiver-child ERH and associated outcomes.

Goal 1: generating foundational knowledge about ERH

Establishing a large prospective ERH-focused cohort of children and their parent(s)/caregiver(s) is critical for deep investigation of the role played by different ERH constructs in health and well-being over the life-course. With increasing understanding for the critical need for “big data”, large multidisciplinary datasets are being established to delve into other key outcomes. Examples include the ABCD study (78) aimed at elucidating the building blocks of brain development from imaging the brains of thousands of children at multiple times during infancy through adolescence, and the RECOVER study (79) aimed at understanding the long-term effects of SARS-CoV-2 infections on a variety of health outcomes. To the best of our knowledge, no ongoing or currently planned similar dataset exists to generate foundational knowledge about ERH.

Goal 1 therefore seeks to expand and leverage existing successful infrastructures (80–83), to develop a large open science dataset by enrolling and following a national cohort of thousands of children and their parent(s)/caregiver(s). Importantly, all efforts will be made to ensure this cohort is “representative of America”, with US census-congruent representation of families of different socioeconomic status, race, and ethnicity.

This data-driven process will ascertain the eco-bio-developmental factors associated with strong ERH and explore the underlying mechanisms of ERH through rigorous data analysis. In collaboration with experts from interconnected and complementary research fields, we will incorporate state-of-the-art methodologies, including machine learning, neural and physiological synchrony, brain imaging, genetics, medicine, and developmental science to establish the foundations of ERH. Importantly, this exploration of ERH will not focus on singular constructs within the field, such as bonding, attachment, emotional connection, or emotional availability, but rather seek to collaboratively generate the most comprehensive picture of ERH through all available lenses and in the context of every family's unique experience, structure, and strengths. For rapid generation and dissemination of actionable knowledge, this dataset will be freely and openly shared with the entire ERH community, with anyone joining the overarching Nurture Connection hub.

A successful example of this type of data-driven process is currently employed by the Center on the Developing Child at Harvard University, which has spearheaded the dissemination of concepts such as toxic stress (84) and serve and return (85), as well as implementation of evidence-based practices building on these concepts (86). Strengths of utilizing this process include the ability to conduct rigorous analyses to isolate mechanisms of change that emphasize internal validity (87, 88), and a large prospective design to identify predictors of ERH (89). In alignment with the ERH Learning Community's research agenda discussion resulting from the co-design activity, this data-driven process will innovate by emphasizing a strengths-based focus on positive predictors, mediators, and outcomes of ERH, including positive childhood experiences (PCEs) as opposed to ACEs, and flourishing and thriving as opposed to mental health disorders.

Goal 2: ERH promotion in pediatric primary care

The practice-informed process brings the research within the context of practice (90) to explore together with families, practitioners and communities what strategies work, for whom, and under which conditions. Consistent with the themes in our co-design activity, we propose to use the established Reach Out and Read large network of pediatric primary care clinics and clinicians as a platform for the practice-informed process. The Reach Out and Read model has been integrated successfully into more than 6,000 clinics across the U.S. and is an ideal platform for practice-based research on ERH. There is a strong evidence base documenting the effectiveness of integration of Reach Out and Read into pediatric primary care (91). Critically, this network offers broad representation from a range of pediatric primary care settings, including all major US geographic areas, rural and urban settings, and professional contexts (e.g., academic/private/community practices and pediatric/family medicine specialties). Drawing from broader literature, initiatives embedded in primary care, such as the Developmental Understanding and Legal Collaboration for Everyone (DULCE) approach, have demonstrated the advantages of leveraging well-child visits to improve pediatric health care and family outcomes at scale (92). As noted previously, limited experimental evidence is available to support timely implementation of evidence-based interventions in the realm of ERH (62). Given the uniqueness of this endeavor, though, we propose starting with pediatric primary care as a foundation, in partnership with Rearch Out and Read, which may lead to rethinking primary care (61) and to new avenues for further exploration.

We will employ Community Activated Research [i.e., engaging parents/caregivers/communities in the research process and giving their voices high priority (93)] to ensure integration of co-design with parents/caregivers, clinicians and communities. To generate knowledge within practice, community activated research will be supplemented by methodologies such as real-world pragmatic designs (94), qualitative research, continued quality improvement [CQI; e.g., quick learning cycles, such as Plan-Do-Study-Act (PDSA)], implementation science (95). Knowledge generated can be used for internal improvement within an organization (96), or disseminated through learning networks (97).

Our research will include determination of the factors that strengthen the clinician-parent/caregiver-infant relationship and ensure integration of effective real-world promotion of ERH into pediatric primary care; development and evaluation of tools to equip pediatric clinicians to both observe and promote ERH; and cultivation of adaptations of the well-child visit that provide opportunities for interventions that effectively advance ERH.

This practice-informed process, which emphasizes external validity, will support the identification of ERH innovations that can be successfully implemented within a variety of health care and related settings (e.g., team-based care, family practice), and with diverse communities. Current successful examples of this methodology include the Home Visiting Collaborative Improvement and Innovation Network (HV CoIIN), which employs CQI to improve the quality of home visiting programs (98), and the IDEAS Impact Framework, which employs rapid-cycle testing to generate evidence for early childhood programs (99). Strengths of this process include higher likelihood of successful implementation due to stronger understanding of practical considerations, shorter timeline to share and scale evidence-informed innovations, and greater considerations of cultural aspects that may influence ERH and its promotion within the pediatric primary care setting.

The homerun: combining evidence-based practice and practice-informed evidence

The most innovative aspect of our research approach is our intention to utilize both evidence-based practice and practice-informed evidence methodologies in a seamless and integrated manner. In other words, to operationalize this approach, we will leverage the large dataset established in our data-driven process to explore mechanisms that support ERH (and the individual variation in the influence of eco-bio-developmental factors on ERH) and feed this knowledge into our practice-informed research. At the same time, the practice-informed research will define feasible practice to cycle back and further test through the data-driven process. The evidence-based practice and practice-informed evidence research will be operated simultaneously, in continuous cycles, each with their specific research methodologies. Findings will be disseminated through our network to inform future cycles of evidence-based practice and practice-informed evidence research. For example, research questions can be generated by any member or affiliate of the ERH Learning Community, including academic researchers, parents/caregivers, and clinicians. Our extensive dataset will allow for a rapid examination of both predictors of ERH, as well as how ERH predicts later outcomes. Identified mechanisms will inform the development of promising new practices that improve ERH. Likewise, promising strategies arising from the practice-informed methodology will inform new hypotheses for mechanisms underlying strong ERH. This combined approach is uniquely promising in answering: what works for improving ERH, for whom do certain supports/interventions work, and under what contexts do these supports/interventions work best (100, 101). In conjunction with traditional hypothesis-driven research (102), we will leverage increasingly popular inductive analytic processes to explore patterns both within the large datasets, as well as through practice-based innovations (103). This inductive, dual-research approach will allow for a high level of collaboration and connection between both research methodologies, ensuring both internal and external validity are valued and maximized throughout the learning and innovation process (104).

The culmination of this integrative research approach will be to achieve population health impacts. We anticipate our preliminary work in the prior years will have demonstrated both testable and promising strategies that improve ERH and subsequent child development, as well as the conditions and context necessary to embed and scale a program or set of practices. Once these advances are achieved, it will be critical to test our assumptions and to demonstrate the impact of our intervention program to generate the level of evidence required for widespread policy changes. We anticipate this demonstration will result from large-scale rigorous mixed methodologies, including a randomized controlled trial (RCT) as a strong basis for supporting causal inference between our proposed innovations and population health impacts. Findings will be communicated through traditional scientific dissemination of results through publications and presentations as well as to a variety of audiences through Nurture Connection (e.g., policymakers, early educators, health care clinicians) to broadly support dissemination and implementation of identified evidence-based practices that support ERH.

ERH learning community's commitment to continued self-reflective practice

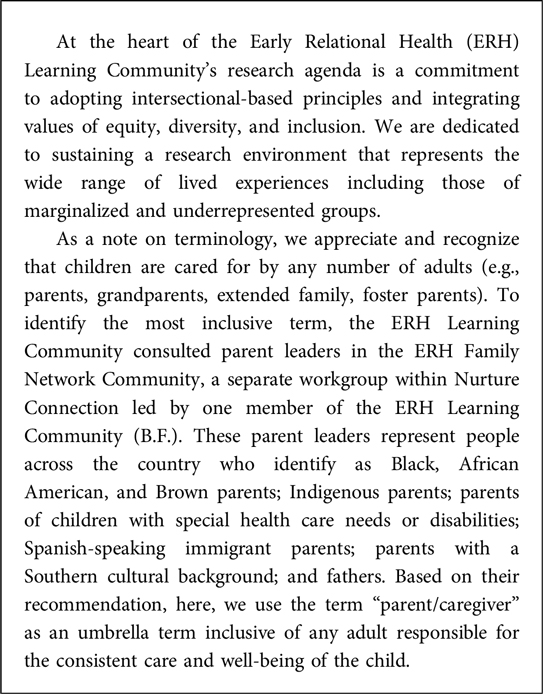

Given the explicit commitment of the ERH Learning Community to creating an inclusive space for ERH conversations to occur with parents/caregivers at the core of a values-based approach, we are committed to continued examination of our biases. In an online meeting of the ERH Learning Community to review a draft of this article, discussion reflected on the importance of ensuring that promotion of ERH occurs in partnership with parents/caregivers; that we appreciate the systemic barriers to health and well-being faced by many under-resourced and marginalized communities; that we embrace the wide range of adults that participate in raising children across a diversity of cultures; that we recognize the negative connotation for many families of words like “resilience” and “stakeholder.” This discussion prompted attention to these considerations throughout this article, in particular in our Reflexivity Statement (Box 2).

Going forward, to supplement the process of co-design activity presented here, a survey expanding on the 3 themes and 14 subthemes will be developed to explore the wider parent/caregiver and clinician communities' perspective on promotion of ERH. Such continued self-reflection may result in revisions and adjustments of the ERH Learning Community's work.

Conclusion

In response to the 2021 AAP policy statement calling for promotion of ERH as a buffer of childhood adversity, the ERH Learning Community co-designed a research agenda to establish an evidence-base that will drive policy and practice within pediatric care to stimulate life-course health and well-being through universal promotion of ERH. We believe that our opportunity for success lies in bringing together a wide range of expertise in this work, including parents, practitioners, and researchers and by leveraging the unique strengths of both a successful academic research longitudinal cohort of parents and young children and an established network of pediatric primary care practices. Our research proposal encompasses a participatory approach with parents/caregivers at the core, that iteratively combines data-driven and practice-informed methodologies to generate foundational knowledge about the eco-bio-developmental factors associated with strong ERH and develop strategies for real-world promotion of ERH in the pediatric primary care setting.

Ethics statement

Ethical review and approval was not required for this study in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent from the program evaluation focus group participants was not required to participate in this study in accordance with the national legislation and the institutional requirements.

Author contributions

DD: Conceptualization, Formal Analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Project administration, Supervision, Validation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Methodology, Visualization, Resources. AL: Data curation, Formal Analysis, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Project administration, Visualization. JR: Conceptualization, Formal Analysis, Investigation, Validation, Writing – review & editing, Methodology, Visualization. CF: Conceptualization, Formal Analysis, Investigation, Validation, Writing – review & editing, Methodology, Visualization. TB: Conceptualization, Formal Analysis, Investigation, Validation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Methodology, Visualization. DB: Writing – review & editing. BB: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing – review & editing, Investigation, Validation. JB: Writing – review & editing. DC: Writing – review & editing. EE: Conceptualization, Investigation, Methodology, Validation, Writing – review & editing. MF: Conceptualization, Investigation, Methodology, Writing – review & editing, Validation. BF: Conceptualization, Investigation, Methodology, Validation, Writing – review & editing. LG: Conceptualization, Formal Analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Writing – review & editing. MM: Conceptualization, Investigation, Methodology, Validation, Writing – review & editing. UR: Conceptualization, Investigation, Validation, Writing – review & editing, Methodology. LS: Conceptualization, Investigation, Methodology, Validation, Writing – review & editing. DW: Conceptualization, Investigation, Methodology, Validation, Writing – review & editing. NS: Conceptualization, Formal Analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Validation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

All phases of this study were supported by gift funds from Einhorn Collaborative to the Department of Pediatrics and Irving Medical Center, Reach Out and Read and Nurture Connection and grant funding from Overdeck to Reach Out and Read.

The authors declare that this study received funding from Einhorn Collaborative and Overdeck. The funders were not involved in the study design, collection, analysis, interpretation of data, the writing of this article or the decision to submit it for publication.

Acknowledgments

Our in-person ERH Learning Community inaugural meeting was convened with funding from Overdeck Family Foundation and with gratitude to the American Academy of Pediatrics for the use of their National Headquarters. We would like to acknowledge Nurture Connection and the Family Network Collaborative (FNC). Finally, we thank Andrew Garner for his engagement with the ERH Learning Community and thoughtful suggestions on this manuscript.

Conflict of interest

BB was employed by company Vav Amani Consulting LLC.

The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1. Center for the Study of Social Policy. Nurture Connection 2023. Available at: https://nurtureconnection.org/about-us/

2. Shonkoff JP, Garner AS. The lifelong effects of early childhood adversity and toxic stress. Pediatrics. (2012) 129(1):e232–46. doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-2663

3. Shim R, Szilagyi M, Perrin JM. Epidemic rates of child and adolescent mental health disorders require an urgent response. Pediatrics. (2022) 149(5):e2022056611. doi: 10.1542/peds.2022-056611

4. AAP, AACAP, CHA. AAP-AACAP-CHA Declaration of a National Emergency in Child and Adolescent Mental Health 2021. Available at: https://www.aap.org/en/advocacy/child-and-adolescent-healthy-mental-development/aap-aacap-cha-declaration-of-a-national-emergency-in-child-and-adolescent-mental-health/

5. AAP, AACAP, CHA. Health Organizations Urge the Biden Administration to Declare a Federal National Emergency in Children’s Mental Health 2022. Available at: https://www.aap.org/en/news-room/news-releases/aap/2022/health-organizations-urge-the-biden-administration-to-declare-a-federal-national-emergency-in-childrens-mental-health/

6. Bitsko RH, Claussen AH, Lichstein J, Black LI, Jones SE, Danielson ML, et al. Mental health surveillance among children—united States, 2013–2019. MMWR supplements. (2022) 71(2):1. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.su7102a1

7. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Our Epidemic of Loneliness and Isolation: The U.S. Surgeon General’s Advisory on the Healing Effects of Social Connection and Community. In: Services HaH, editor. 2023.

8. Holt-Lunstad J. Social connection as a public health issue: the evidence and a systemic framework for prioritizing the “social” in social determinants of health. Annu Rev Public Health. (2022) 43:193–213. doi: 10.1146/annurev-publhealth-052020-110732

9. Atzil S, Gao W, Fradkin I, Barrett LF. Growing a social brain. Nat Hum Behav. (2018) 2(9):624–36. doi: 10.1038/s41562-018-0384-6

10. Okabe-Miyamoto K, Folk D, Lyubomirsky S, Dunn EW. Changes in social connection during COVID-19 social distancing: it’s not (household) size that matters, it’s who you're with. PLoS One. (2021) 16(1):e0245009. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0245009

11. Willis DW, Eddy JM. Early relational health: innovations in child health for promotion, screening, and research. Infant Ment Health J. (2022) 43(3):361–72. doi: 10.1002/imhj.21980

12. Boyce WT, Levitt P, Martinez FD, McEwen BS, Shonkoff JP. Genes, environments, and time: the biology of adversity and resilience. Pediatrics. (2021) 147(2):e20201651. doi: 10.1542/peds.2020-1651

13. Short AK, Baram TZ. Early-life adversity and neurological disease: age-old questions and novel answers. Nat Rev Neurol. (2019) 15(11):657–69. doi: 10.1038/s41582-019-0246-5

14. Oh DL, Jerman P, Silverio Marques S, Koita K, Purewal Boparai SK, Burke Harris N, et al. Systematic review of pediatric health outcomes associated with childhood adversity. BMC Pediatr. (2018) 18(1):83. doi: 10.1186/s12887-018-1037-7

15. Wesarg C, Van den Akker AL, Oei NYL, Wiers RW, Staaks J, Thayer JF, et al. Childhood adversity and vagal regulation: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. (2022) 143:104920. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2022.104920

16. Bradley RH, Corwyn RF. Socioeconomic status and child development. Annu Rev Psychol. (2002) 53:371–99. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.53.100901.135233

17. Evans GW. A multimethodological analysis of cumulative risk and allostatic load among rural children. Dev Psychol. (2003) 39(5):924–33. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.39.5.924

18. Miller GE, Chen E, Parker KJ. Psychological stress in childhood and susceptibility to the chronic diseases of aging: moving toward a model of behavioral and biological mechanisms. Psychol Bull. (2011) 137(6):959–97. doi: 10.1037/a0024768

19. Blair C, Raver CC. Child development in the context of adversity: experiential canalization of brain and behavior. Am Psychol. (2012) 67(4):309–18. doi: 10.1037/a0027493

20. Gilbert LK, Breiding MJ, Merrick MT, Thompson WW, Ford DC, Dhingra SS, et al. Childhood adversity and adult chronic disease: an update from ten states and the district of Columbia, 2010. Am J Prev Med. (2015) 48(3):345–9. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2014.09.006

21. Hughes K, Bellis MA, Hardcastle KA, Sethi D, Butchart A, Mikton C, et al. The effect of multiple adverse childhood experiences on health: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Public Health. (2017) 2(8):e356–e66. doi: 10.1016/S2468-2667(17)30118-4

22. Schurer S, Trajkovski K, Hariharan T. Understanding the mechanisms through which adverse childhood experiences affect lifetime economic outcomes. Labour Econ. (2019) 61:101743. doi: 10.1016/j.labeco.2019.06.007

23. Felitti VJ, Anda RF, Nordenberg D, Williamson DF, Spitz AM, Edwards V, et al. Relationship of childhood abuse and household dysfunction to many of the leading causes of death in adults. The adverse childhood experiences (ACE) study. Am J Prev Med. (1998) 14(4):245–58. doi: 10.1016/S0749-3797(98)00017-8

24. Wade R J, Cronholm PF, Fein JA, Forke CM, Davis MB, Harkins-Schwarz M, et al. Household and community-level adverse childhood experiences and adult health outcomes in a diverse urban population. Child Abuse Negl. (2016) 52:135–45. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2015.11.021

25. Van Lancker W, Parolin Z. COVID-19, school closures, and child poverty: a social crisis in the making. Lancet Public Health. (2020) 5(5):e243–e4. doi: 10.1016/S2468-2667(20)30084-0

26. Lebel C, MacKinnon A, Bagshawe M, Tomfohr-Madsen L, Giesbrecht G. Elevated depression and anxiety symptoms among pregnant individuals during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Affect Disord. (2020) 277:5–13. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2020.07.126

27. Morris AR, Saxbe DE. Mental health and prenatal bonding in pregnant women during the COVID-19 pandemic: evidence for heightened risk compared with a prepandemic sample. Clin Psychol Sci. (2022) 10(5):846–55. doi: 10.1177/21677026211049430

28. Berthelot N, Lemieux R, Garon-Bissonnette J, Drouin-Maziade C, Martel E, Maziade M. Uptrend in distress and psychiatric symptomatology in pregnant women during the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. (2020) 99(7):848–55. doi: 10.1111/aogs.13925

29. Tomfohr-Madsen LM, Racine N, Giesbrecht GF, Lebel C, Madigan S. Depression and anxiety in pregnancy during COVID-19: a rapid review and meta-analysis. Psychiatry Res. (2021) 300:113912. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2021.113912

30. Venta A, Bick J, Bechelli J. COVID-19 threatens maternal mental health and infant development: possible paths from stress and isolation to adverse outcomes and a call for research and practice. Child Psychiatry Hum Dev. (2021) 52(2):200–4. doi: 10.1007/s10578-021-01140-7

31. Cameron EE, Joyce KM, Delaquis CP, Reynolds K, Protudjer JLP, Roos LE. Maternal psychological distress & mental health service use during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Affect Disord. (2020) 276:765–74. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2020.07.081

32. Adams EL, Smith D, Caccavale LJ, Bean MK. Parents are stressed! patterns of parent stress across COVID-19. Front Psychiatry. (2021) 12:626456. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2021.626456

33. Connell CM, Strambler MJ. Experiences with COVID-19 stressors and Parents’ use of neglectful, harsh, and positive parenting practices in the northeastern United States. Child Maltreat. (2021) 26(3):255–66. doi: 10.1177/10775595211006465

34. Frankel LA, Kuno CB, Sampige R. The relationship between COVID-related parenting stress, nonresponsive feeding behaviors, and parent mental health. Curr Psychol. (2021) 42:1–12. doi: 10.1007/s12144-021-02333-y

35. Perzow SED, Hennessey EP, Hoffman MC, Grote NK, Davis EP, Hankin BL. Mental health of pregnant and postpartum women in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. J Affect Disord Rep. (2021) 4:100123. doi: 10.1016/j.jadr.2021.100123

36. Rapp A, Fall G, Radomsky AC, Santarossa S. Child maltreatment during the COVID-19 pandemic: a systematic rapid review. Pediatr Clin North Am. (2021) 68(5):991–1009. doi: 10.1016/j.pcl.2021.05.006

37. Katz I, Priolo-Filho S, Katz C, Andresen S, Berube A, Cohen N, et al. One year into COVID-19: what have we learned about child maltreatment reports and child protective service responses? Child Abuse Negl. 2022;130(Pt 1):105473. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2021.105473

38. Humphreys KL, Myint MT, Zeanah CH. Increased risk for family violence during the COVID-19 pandemic. Pediatrics. (2020) 146(1):e20200982. doi: 10.1542/peds.2020-0982

39. Bhuptani PH, Hunter J, Goodwin C, Millman C, Orchowski LM. Characterizing intimate partner violence in the United States during the COVID-19 pandemic: a systematic review. Trauma Violence Abuse. (2022) 24(5):15248380221126187. doi: 10.1177/15248380221126

40. Piquero AR, Jennings WG, Jemison E, Kaukinen C, Knaul FM. Domestic violence during the COVID-19 pandemic—evidence from a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Crim Justice. (2021) 74:101806. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrimjus.2021.101806

41. Boserup B, McKenney M, Elkbuli A. Alarming trends in US domestic violence during the COVID-19 pandemic. Am J Emerg Med. (2020) 38(12):2753–5. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2020.04.077

42. Jetelina KK, Knell G, Molsberry RJ. Changes in intimate partner violence during the early stages of the COVID-19 pandemic in the USA. Inj Prev. (2021) 27(1):93–7. doi: 10.1136/injuryprev-2020-043831

43. Abraham P, Williams E, Bishay AE, Farah I, Tamayo-Murillo D, Newton IG. The roots of structural racism in the United States and their manifestations during the COVID-19 pandemic. Acad Radiol. (2021) 28(7):893–902. doi: 10.1016/j.acra.2021.03.025

44. Tai DBG, Shah A, Doubeni CA, Sia IG, Wieland ML. The disproportionate impact of COVID-19 on racial and ethnic minorities in the United States. Clin Infect Dis. (2021) 72(4):703–6. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa815

45. Hillis SD, Blenkinsop A, Villaveces A, Annor FB, Liburd L, Massetti GM, et al. COVID-19-Associated orphanhood and caregiver death in the United States. Pediatrics. (2021) 148(6):e2021053760. doi: 10.1542/peds.2021-053760

46. Lee SJ, Ward KP, Lee JY, Rodriguez CM. Parental social isolation and child maltreatment risk during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Fam Violence. (2022) 37(5):813–24. doi: 10.1007/s10896-020-00244-3

47. O’Sullivan R, Burns A, Leavey G, Leroi I, Burholt V, Lubben J, et al. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on loneliness and social isolation: a multi-country study. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2021) 18(19). doi: 10.3390/ijerph18199982

48. Ellis WR, Dietz WH. A new framework for addressing adverse childhood and community experiences: the building community resilience model. Acad Pediatr. (2017) 17(7S):S86–93. doi: 10.1016/j.acap.2016.12.011

49. Esposito G, Setoh P, Shinohara K, Bornstein MH. The development of attachment: integrating genes, brain, behavior, and environment. Behav Brain Res. (2017) 325(Pt B):87–9. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2017.03.025

50. Wright N, Hill J, Sharp H, Pickles A. Maternal sensitivity to distress, attachment and the development of callous-unemotional traits in young children. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. (2018) 59(7):790–800. doi: 10.1111/jcpp.12867

51. Garner A, Yogman M. Committee on psychosocial aspects of C, family health SOD, behavioral pediatrics COEC. Preventing childhood toxic stress: partnering with families and communities to promote relational health. Pediatrics. (2021) 148(2):e2021052582. doi: 10.1542/peds.2021-052582

52. Traub F, Boynton-Jarrett R. Modifiable resilience factors to childhood adversity for clinical pediatric practice. Pediatrics. (2017) 139(5):e20162569. doi: 10.1542/peds.2016-2569

53. Morris AS, Robinson LR, Hays-Grudo J, Claussen AH, Hartwig SA, Treat AE. Targeting parenting in early childhood: a public health approach to improve outcomes for children living in poverty. Child Dev. (2017) 88(2):388–97. doi: 10.1111/cdev.12743

54. Stein A, Malmberg LE, Leach P, Barnes J, Sylva K. The influence of different forms of early childcare on children’s emotional and behavioural development at school entry. Child Care Health Dev. (2013) 39(5):676–87. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2214.2012.01421.x

55. Hambrick EP, Brawner TW, Perry BD, Brandt K, Hofmeister C, Collins JO. Beyond the ACE score: examining relationships between timing of developmental adversity, relational health and developmental outcomes in children. Arch Psychiatr Nurs. (2019) 33(3):238–47. doi: 10.1016/j.apnu.2018.11.001

56. Boudreau A, Hamling A, Pont E, Pendergrass TW, Richerson J, Simon HK, et al. Pediatric primary health care: the central role of pediatricians in maintaining children’s health in evolving health care models. Pediatrics. (2022) 149(2):e2021055553. doi: 10.1542/peds.2021-055553

57. Wolf ER, Hochheimer CJ, Sabo RT, DeVoe J, Wasserman R, Geissal E, et al. Gaps in well-child care attendance among primary care clinics serving low-income families. Pediatrics. (2018) 142(5):e20174019. doi: 10.1542/peds.2017-4019

58. Ray KN, Shi Z, Ganguli I, Rao A, Orav EJ, Mehrotra A. Trends in pediatric primary care visits among commercially insured US children, 2008–2016. JAMA Pediatr. (2020) 174(4):350–7. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2019.5509

59. Gresh A, Ahmed N, Boynton-Jarrett R, Sharifi M, Rosenthal MS, Fenick AM. Clinicians’ perspectives on equitable health care delivery in group well-child care. Acad Pediatr. (2023) 23(7):1385–93. doi: 10.1016/j.acap.2023.06.010

60. Gaskin E, Yorga KW, Berman R, Allison M, Sheeder J. Pediatric group care: a systematic review. Matern Child Health J. (2021) 25(10):1526–53. doi: 10.1007/s10995-021-03170-y

61. Needlman R. Thoughts on health supervision: learning-focused primary care. Pediatrics. (2006) 117(6):e1233–6. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-1826

62. Lavallée A, Pang L, Warmingham JM, Atwood G, Ahmed I, Lanoff M, et al. Early dyadic parent/caregiver-infant interventions to support early relational health: a meta-analysis. medRxiv. (2022):e1–31. doi: 10.1101/2022.10.29.22281681

63. Cooke JE, Kochendorfer LB, Stuart-Parrigon KL, Koehn AJ, Kerns KA. Parent-child attachment and children’s experience and regulation of emotion: a meta-analytic review. Emotion. (2019) 19(6):1103–26. doi: 10.1037/emo0000504

64. Deneault AA, Hammond SI, Madigan S. A meta-analysis of child-parent attachment in early childhood and prosociality. Dev Psychol. (2023) 59(2):236–55. doi: 10.1037/dev0001484

65. Le Bas GA, Youssef GJ, Macdonald JA, Rossen L, Teague SJ, Kothe EJ, et al. The role of antenatal and postnatal maternal bonding in infant development: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Social Development. (2020) 29(1):3–20. doi: 10.1111/sode.12392

66. Madigan S, Prime H, Graham SA, Rodrigues M, Anderson N, Khoury J, et al. Parenting behavior and child language: a meta-analysis. Pediatrics. (2019) 144(4):e20183556. doi: 10.1542/peds.2018-3556

67. Pallini S, Morelli M, Chirumbolo A, Baiocco R, Laghi F, Eisenberg N. Attachment and attention problems: a meta-analysis. Clin Psychol Rev. (2019) 74:101772. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2019.101772

68. Rodrigues M, Sokolovic N, Madigan S, Luo Y, Silva V, Misra S, et al. Paternal sensitivity and children’s cognitive and socioemotional outcomes: a meta-analytic review. Child Dev. (2021) 92(2):554–77. doi: 10.1111/cdev.13545

69. Cates CB, Weisleder A, Berkule Johnson S, Seery AM, Canfield CF, Huberman H, et al. Enhancing parent talk, Reading, and play in primary care: sustained impacts of the video interaction project. J Pediatr. (2018) 199:49–56.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2018.03.002

70. Roby E, Miller EB, Shaw DS, Morris P, Gill A, Bogen DL, et al. Improving parent-child interactions in pediatric health care: a two-site randomized controlled trial. Pediatrics. (2021) 147(3):e20201799. doi: 10.1542/peds.2020-1799

71. Mendelsohn AL, Valdez PT, Flynn V, Foley GM, Berkule SB, Tomopoulos S, et al. Use of videotaped interactions during pediatric well-child care: impact at 33 months on parenting and on child development. J Dev Behav Pediatr. (2007) 28(3):206–12. doi: 10.1097/DBP.0b013e3180324d87

72. Micheli P, Wilner SJS, Bhatti SH, Mura M, Beverland MB. Doing design thinking: conceptual review, synthesis, and research agenda. J Prod Innov Manag. (2019) 36(2):124–48. doi: 10.1111/jpim.12466

73. Birt L, Scott S, Cavers D, Campbell C, Walter F. Member checking: a tool to enhance trustworthiness or merely a nod to validation? Qual Health Res. (2016) 26(13):1802–11. doi: 10.1177/1049732316654870

74. Greene-Moton E, Minkler M. Cultural competence or cultural humility? Moving beyond the debate. Health Promot Pract. (2020) 21(1):142–5. doi: 10.1177/1524839919884912

75. Committee on Psychosocial Aspects of Child and Family Health, Committee on Early Childhood, Adoption, and Dependent Care, and Section on Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics; Garner AS, Shonkoff JP, Siegel BS, Dobbins MI, Earls MF, et al. Early childhood adversity, toxic stress, and the role of the pediatrician: translating developmental science into lifelong health. Pediatrics. (2012);129(1):e224–31. doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-2662

76. Shonkoff JP, Garner AS, The Committee on Psychosocial Aspects of Child and Family Health, Committee on Early Childhood, Adoption, and Dependent Care, and Section on Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics; Siegel BS, Dobbins MI, Earls MF, et al. The lifelong effects of early childhood adversity and toxic stress. Pediatrics. (2012);129(1):e232–46. doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-2663

77. Shonkoff JP, Boyce WT, Levitt P, Martinez FD, McEwen B. Leveraging the biology of adversity and resilience to transform pediatric practice. Pediatrics. (2021) 147(2):e20193845. doi: 10.1542/peds.2019-3845

78. Volkow ND, Koob GF, Croyle RT, Bianchi DW, Gordon JA, Koroshetz WJ, et al. The conception of the ABCD study: from substance use to a broad NIH collaboration. Dev Cogn Neurosci. (2018) 32:4–7. doi: 10.1016/j.dcn.2017.10.002

79. Katz S, Troxel A, Horwitz L, Snowden J, Warburton D, Stockwell M, et al. Study Title: A Multi-Center Observational Study: The RECOVER Post Acute Sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 (PASC) Pediatric Cohort Study2022. Available at: https://recovercovid.org/sites/default/files/docs/PediatricProtocol.v2.3.pdf

80. Connor Garbe M, Bond SL, Boulware C, Merrifield C, Ramos-Hardy T, Dunlap M, et al. The effect of exposure to reach out and read on shared Reading behaviors. Acad Pediatr. (2023) 23(8):1598–1604. doi: 10.1016/j.acap.2023.06.030

81. Bianco C, Sania A, Kyle MH, Beebe B, Barbosa J, Bence M, et al. Pandemic beyond the virus: maternal COVID-related postnatal stress is associated with infant temperament. Pediatr Res. (2023) 93(1):253–9. doi: 10.1038/s41390-022-02071-2

82. Lavallée A, Warmingham JM, Reimers MA, Kyle MH, Austin J, Lee S, et al. Factor structure of the postpartum bonding questionnaire in a US-based cohort of mothers. medRxiv. (2023):e1–12. doi: 10.1101/2023.04.09.23288334

83. Shuffrey LC, Firestein MR, Kyle MH, Fields A, Alcantara C, Amso D, et al. Association of birth during the COVID-19 pandemic with neurodevelopmental Status at 6 months in infants with and without in utero exposure to maternal SARS-CoV-2 infection. JAMA Pediatr. (2022) 176(6):e215563. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2021.5563

84. National Scientific Council on the Developing Child. Excessive Stress Disrupts the Architecture of the Developing Brain: Working Paper No. 3.2005/2014. Available at: https://developingchild.harvard.edu/wp-content/uploads/2005/05/Stress_Disrupts_Architecture_Developing_Brain-1.pdf

85. National Scientific Council on the Developing Child. Young Children Develop in an Environment of Relationships: Working Paper No. 12004. Available at: https://developingchild.harvard.edu/wp-content/uploads/2004/04/Young-Children-Develop-in-an-Environment-of-Relationships.pdf

86. Shonkoff JP, Fisher PA. Rethinking evidence-based practice and two-generation programs to create the future of early childhood policy. Dev Psychopathol. (2013) 25(4 Pt 2):1635–53. doi: 10.1017/S0954579413000813

87. Black N. Why we need observational studies to evaluate the effectiveness of health care. Br Med J. (1996) 312(7040):1215–8. doi: 10.1136/bmj.312.7040.1215

88. Concato J, Shah N, Horwitz RI. Randomized, controlled trials, observational studies, and the hierarchy of research designs. N Engl J Med. (2000) 342(25):1887–92. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200006223422507

89. Caruana EJ, Roman M, Hernandez-Sanchez J, Solli P. Longitudinal studies. J Thorac Dis. (2015) 7(11):E537–40. doi: 10.3978/j.issn.2072-1439.2015.10.63

90. Green LW. Making research relevant: if it is an evidence-based practice, where’s the practice-based evidence? Fam Pract. (2008) 25(Suppl 1):i20–4. doi: 10.1093/fampra/cmn055

91. Reach Out and Read. Why we matter n.d. Available at: https://reachoutandread.org/why-we-matter/the-evidence/

92. Arbour MC, Floyd B, Morton S, Hampton P, Sims JM, Doyle S, et al. Cross-Sector approach expands screening and addresses health-related social needs in primary care. Pediatrics. (2021) 148(5):e2021050152. doi: 10.1542/peds.2021-050152

93. Chen E, Leos C, Kowitt SD, Moracco KE. Enhancing community-based participatory research through human-centered design strategies. Health Promot Pract. (2020) 21(1):37–48. doi: 10.1177/1524839919850557

94. Sox HC, Lewis RJ. Pragmatic trials: practical answers to “real world” questions. JAMA. (2016) 316(11):1205–6. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.11409

95. Peters DH, Adam T, Alonge O, Agyepong IA, Tran N. Implementation research: what it is and how to do it. Br Med J. (2013) 347:f6753. doi: 10.1136/bmj.f7086

96. McLaughlin CP, Kaluzny AD. Continuous quality improvement in health care: theory, implementation, and applications: Jones & Bartlett Learning; 2004).

97. Bryk AS, Gomez LM, Grunow A, LeMahieu PG. Learning to improve: How America’s schools can get better at getting better. Cambridge, MA: Harvard Education Press (2015).

98. Arbour M, Mackrain M, Cano C, Atwood S, Dworkin P. National home visiting collaborative improves developmental risk detection and service linkage. Acad Pediatr. (2021) 21(5):809–17. doi: 10.1016/j.acap.2020.08.020

99. Fisher PA, Barker TV, Blaisdell KN. A glass half full and half empty: the state of the science in early childhood prevention and intervention research. Ann Rev Develop Psychol. (2020) 2(1):269–94. doi: 10.1146/annurev-devpsych-121318-084958

101. Porter S. The uncritical realism of realist evaluation. Eval. (2015) 21(1):65–82. doi: 10.1177/1356389014566134

102. Rozeboom WW. Good science is abductive, not hypothetico-deductive. What if there were no significance tests? New Jersey: Routledge (2016). 349–400.

103. Grice JW. Observation oriented modeling: analysis of cause in the behavioral sciences. Cambridge, MA: Academic Press (2011).

Keywords: pediatrics, nurture, connection, parents, caregivers, centrality of relationships, early relational health, parent-child interactions

Citation: Dumitriu D, Lavallée A, Riggs JL, Frosch CA, Barker TV, Best DL, Blasingame B, Bushar J, Charlot-Swilley D, Erickson E, Finkel MA, Fortune B, Gillen L, Martinez M, Ramachandran U, Sanders LM, Willis DW and Shearman N (2023) Advancing early relational health: a collaborative exploration of a research agenda. Front. Pediatr. 11:1259022. doi: 10.3389/fped.2023.1259022

Received: 14 July 2023; Accepted: 7 November 2023;

Published: 7 December 2023.

Edited by:

Zephanie Tyack, Queensland University of Technology, AustraliaReviewed by:

Victoria A. Grunberg, Harvard Medical School, United StatesDavid Keller, University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus, United States

© 2023 Dumitriu, Lavallée, Riggs, Frosch, Barker, Best, Blasingame, Bushar, Charlot-Swilley, Erickson, Finkel, Fortune, Gillen, Martinez, Ramachandran, Sanders, Willis and Shearman. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Dani Dumitriu dani.dumitriu@columbia.edu

†These authors share first authorship

Abbreviations AACAP, American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry; AAP, American Academy of Pediatrics; ACE, adverse childhood experiences; CHA, Children's Hospital Association; CSSP, Center for the Study of Social Policy; ERH, early relational health; ERH-C, early relational health conversations; FNC, Family Network Collaborative; PCE, positive childhood experiences; ROR, Reach Out and Read.

‡ORCID Dani Dumitriu orcid.org/0000-0002-7873-5192 Andréane Lavallée orcid.org/0000-0001-5702-3084

Dani Dumitriu

Dani Dumitriu Andréane Lavallée

Andréane Lavallée Jessica L. Riggs

Jessica L. Riggs Cynthia A. Frosch

Cynthia A. Frosch Tyson V. Barker5

Tyson V. Barker5  Debra L. Best

Debra L. Best