Adoptive Immunotherapy With Engineered iNKT Cells to Target Cancer Cells and the Suppressive Microenvironment

- 1Experimental Immunology Unit, Division of Immunology, Transplantation, and Infectious Diseases, Istituto di Ricovero e Cura a Carattere Scientifico (IRCCS) San Raffaele Scientific Institute, Milan, Italy

- 2Vita-Salute San Raffaele University, Milan, Italy

Invariant Natural Killer T (iNKT) cells are T lymphocytes expressing a conserved semi-invariant TCR specific for lipid antigens (Ags) restricted for the monomorphic MHC class I-related molecule CD1d. iNKT cells infiltrate mouse and human tumors and play an important role in the immune surveillance against solid and hematological malignancies. Because of unique functional features, they are attractive platforms for adoptive cells immunotherapy of cancer compared to conventional T cells. iNKT cells can directly kill CD1d-expressing cancer cells, but also restrict immunosuppressive myelomonocytic populations in the tumor microenvironment (TME) via CD1d-cognate recognition, promoting anti-tumor responses irrespective of the CD1d expression by cancer cells. Moreover, iNKT cells can be adoptively transferred across MHC barriers without risk of alloreaction because CD1d molecules are identical in all individuals, in addition to their ability to suppress graft vs. host disease (GvHD) without impairing the anti-tumor responses. Within this functional framework, iNKT cells are successfully engineered to acquire a second antigen-specificity by expressing recombinant TCRs or Chimeric Antigen Receptor (CAR) specific for tumor-associated antigens, enabling the direct targeting of antigen-expressing cancer cells, while maintaining their CD1d-dependent functions. These new evidences support the exploitation of iNKT cells for donor unrestricted, and possibly off the shelf, adoptive cell therapies enabling the concurrent targeting of cancer cells and suppressive microenvironment.

Introduction

Natural killer T cells (NKT cells) were originally characterized in mice as T cells that express both a TCR and NK1.1 (NKR-P1a-c or CD161), a C-type lectin NK receptor (1–3). Invariant NKT (iNKT) cells (or type I NKT cells) express a semi-invariant αβ TCR, formed by an invariant TRAV11-TRAJ18 (4) rearrangement in mice, or the homologous invariant TRAV10-TRAJ18 chain in humans (5), paired with a limited set of diverse Vβ chains, predominantly TRBV1, TRBV29, or TRBV13 in mice (6) and TRBV25 in humans (5). The semi-invariant TCR recognizes exogenous and endogenous lipid Ags presented by the monomorphic MHC class I-related molecule CD1d (7). Exogenous lipid Ags include the prototypical α-Galactosylceramide (α-GalCer) (8) and a number of bacterial-derived Ags (9). In addition, one of the iNKT cell functional hallmarks is their avid autoreactivity upon recognition of stress-associated cell endogenous lipids (10–13).

iNKT cells undergo a distinct developmental pathway compared to T cells, leading to the acquisition of innate effector functions already in the thymus. Thymic iNKT cells indeed express markers usually upregulated by peripheral effector/memory T cells, such as CD44 and CD69, together with distinctive NK differentiation markers, such as NK1.1 (in some mouse genetic backgrounds, CD161 in humans), CD122 (the IL-2R/IL-15R β-chain), CD94/NKG2 and Ly49(A-J), and a broad spectrum of TH1/2/17 effector cytokines (6).

Once migrated in the periphery, iNKT cells form a tissue resident population that survey the cellular integrity and rapidly respond to local damage and inflammation, jump starting the reaction by cells of the innate and adaptive immune response. In mice, iNKT cells with specific TH1, TH2 and/or TH17 effector profiles differentially colonize peripheral organs, resulting in the accumulation of specialized functions (14), whereas in humans it is more difficult to identify functional subsets beyond the two main CD4+ TH0 and CD4− TH1 (15).

Amid functions exerted by iNKT cells in tissues, their active participation in the immune surveillance against malignant transformation and tumor progression is particularly well-established, strongly supporting their use in cancer immunotherapy. In this review, we will outline the advantages of harnessing iNKT cells particularly for adoptive immunotherapy, also when compared to conventional αβ T cells, given that they: (i) Control the tumor microenvironment (TME); (ii) Can be redirected against cancer cells by engineering with a tumor-specific CAR or TCR while maintaining their intrinsic control of the TME; (iii) Are devoid of alloreactivity, being restricted for the monomorphic CD1d molecule, allowing their possible use off the shelf in a donor-unrestricted manner.

Role of iNKT Cells in Anti-Tumor Immune Response

The role of iNKT cells in anti-tumor immune response first emerged with the demonstration that the systemic administration of IL-12 (16) or α-GalCer into tumor-bearing mice resulted in iNKT cell activation, in turn promoting anti-tumor CD8+ T and NK cell responses able to control tumor progression (17–22). iNKT cells were also shown to exert spontaneous immune surveillance (i.e. without exogenous Ag stimulation) against methylcholanthrene-induced sarcomas or different genetically engineered mouse tumor models of sarcoma, lymphoma, prostate adenocarcinoma, Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia (CLL) and pancreatic adenocarcinoma (23–30). In these studies, iNKT cell-deficient mice generated by the deletion of the genes encoding the invariant TRAJ18 TCR chain (Jα18−/−) or CD1d (CD1d−/−) were challenged with methylcholanthrene or crossed with tumor-predisposing genetically engineered strains, resulting in earlier onset and higher incidence of cancer with reduced survival. Adoptive transfer of iNKT cells into Jα18−/− tumor bearing mice restored the protection against cancer, in the absence of exogenous stimulation (23, 30). Of note, the main CD4+ and CD4− iNKT cell subsets were not equally effective in tumor control: in fact, liver-derived CD4− iNKT cells were found to be the main mediators of tumor immune surveillance in vivo, by sustaining a TH1-type CD8+ T and NK cell-mediated immune response via IFNγ production (23).

In humans, clinical studies reported reduced frequencies and functional impairment of iNKT cells in patients with a wide range of solid and hematological malignancies (31). A decreased number and/or frequency of circulating iNKT cells associated with poor overall survival in prostate cancer (32), head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (33), neuroblastoma (34) acute myeloid leukemia (AML) (35) and CLL (24). Conversely, high numbers of intra-tumoral or circulating iNKT cells correlated with a good clinical outcome and improved survival in colorectal cancer (36), neuroblastoma (37), periampullary adenocarcinoma (38) and hematologic malignancies (39, 40), whereas circulating iNKT cells often become functionally impaired in patients with progressing cancers. In prostate cancer and in oral cell squamous carcinoma, iNKT cells have a defective production of IFNγ, acquiring a TH2 biased cytokine profile (41, 42). This defect can be reverted in vitro by activating the patient-derived iNKT cells in the presence of IL-2 or IL-12 (41), or in vivo upon therapeutic administration of autologous dendritic cells (DCs) pre-loaded with α-GalCer (43, 44). Studies in cancer patients also showed that iNKT cells respond to chemotactic signals derived from tumor cells, or cells of the tumor microenvironment, and infiltrate different types of primary and metastatic solid tumors (30, 45). iNKT cells infiltration in neuroblastoma is associated to CCL2 expression on tumor cells and CCL20 producing-TAMs, and iNKT cells preferentially infiltrate tumors that express high levels of this chemokine (46, 47).

Mechanisms of Tumor Control by iNKT Cells

iNKT cells can control tumor progression by direct or indirect mechanisms. They can directly recognize and kill CD1d-expressing malignant cells, which are mainly hematopoietic malignancies (45, 48, 49). The mechanisms of direct killing include perforin/granzyme B-mediated cytolysis, TNFα production and TRAIL- and FasL- dependent apoptosis (29, 50, 51). However, what tumor associated lipid antigen/s iNKT cells recognize on cancer cells is currently unknown. Malignant cells can synthetize ganglioside GD3 that can stimulate iNKT cells in vivo (52); yet, it is likely that additional stress-related lipid antigens may be produced by cancer cells and presented to iNKT cells. Also in human cancers CD1d is mainly expressed by the hematopoietic ones (45), whereas very few solid tumors are CD1d-positive (53–55). Furthermore, cancer cells can downregulate CD1d surface expression, thereby limiting direct recognition by iNKT cells (55–57), even though they have shown to kill by perforin and/or granzymes at least colon cancer cells also in a CD1d-independent manner (58). The mechanisms underlying CD1d downregulation or loss by cancer cells are largely unknown. β-2 microglobulin loss, which can occur in progressing tumors, could affect CD1d in addition to MHC-I expression, while epigenetic silencing of MHC-I gene expression might also affect CD1d gene epigenetic control. Nevertheless, the available experimental data suggest that iNKT cells mainly control tumors by indirect mechanisms that impact the tumor microenvironment. iNKT cells promote the anti-tumor immune response through the maturation of CD1d+ DCs and the secretion of IFNγ and IL-12, in turn leading to the activation of anti-tumor CD4+ and CD8+ T cells and of NK cells, which ultimately cooperate in the elimination of both MHC-positive and -negative cancer cells (32, 59). Furthermore, more recent evidence shows that iNKT cells efficiently reprogram immunostimulatory functions of the TME by modulating myelomonocytic populations.

iNKT Cells Shape the TME

Cancer cells undergo a progressive selection process in which a continuous and reciprocal cross-talk with the surrounding non-malignant cells of the TME plays a fundamental role for their growth and spread. Cells of both adaptive and innate immune response infiltrate the tumor stroma accounting for a major proportion of the TME (60, 61). Tumor infiltrating effector T cells, which can recognize tumor associated antigens (TAA) and selectively eliminate cancer cells together with NK cells, are in a critical equilibrium with immunosuppressive CD4+CD25+Foxp3+ Tregs, providing one known mechanism determining tumor control vs. progression (62). The TME contains also B cells that can associate to either control or promotion of tumor progression (63, 64) and, especially, myelomonocytic cells that are the most abundant tumor infiltrating leukocyte population, accounting for up to 50% of the tumor mass (65). Tumor associated macrophages (TAMs) may have either tumor-opposing or promoting functions (66). An over-simplified model identifies TAMs with pro-inflammatory, immunostimulatory anti-tumor functions (M1-like), opposed to TAMs with pro-angiogenic, immunoregulatory tumor-supporting ability (M2-like) (65, 67–73). Tumor associated neutrophils (TANs), like TAMs, can be differently activated to support tumor progression or enhance their antitumor functions (74, 75), ranging from a pro-inflammatory N1 to a suppressive N2 state (76). Tumor infiltrating Myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSC), which can be divided in polymorphonuclear (PMN) and monocytic (M) MDSCs (77), exert unequivocal tumor-promoting activity (78); and can influence virtually every type of cancer therapy, from chemo-radiation to immunotherapy (61). DCs are also critical for eliciting potent anti-tumor T-cell responses, and patients with higher migratory CD103+ DCs have significantly increased overall survival (79). Cancer cells have also the ability to recruit cells from nearby stroma: in different tumors, stromal cell composition can vary substantially, including fibroblasts, vascular endothelial cells, stellate cells, and adipocytes. These cells secrete factors influencing proliferation, invasion, metastasization, and angiogenesis, but also antitumour immunity and responsiveness to immunotherapy (80). Overall, the functional plasticity of the immune cells in the TME defines a potential Achilles heel of the tumor, because reprogramming a dysfunctional TME toward a tumor-opposing state, in combination with the most advanced therapies, could result in cancer control and possibly remission (81).

iNKT cells actively infiltrate tumors. In hepatocellular carcinoma patients, the frequency of iNKT cells among CD3+ intrahepatic lymphocytes was similar to that found in peripheral blood (0.133%), but the iNKT cell frequency in tumor infiltrating lymphocytes coming from matched samples was doubled (0.271%) (82). An immunohistochemistry study showed that a small number of Vα24+ NKT cells was detected in the normal colorectal mucosa (2.6 +/– 3.7 cells/5 HPF), whereas a remarkably higher number was found in colorectal adenocarcinomas (15.2 +/– 16.3 cells/5 HPF), acquiring an independent prognostic value for the overall and disease-free survival rates (36). Vα24-Jα18 TCR mRNA expression was also detected in 53% (34) or 57% (37) of neuroblastoma cases, which also showed an higher overall survival rate compared to the patients in which the iNKT cell TCR could not be detected (34, 37).

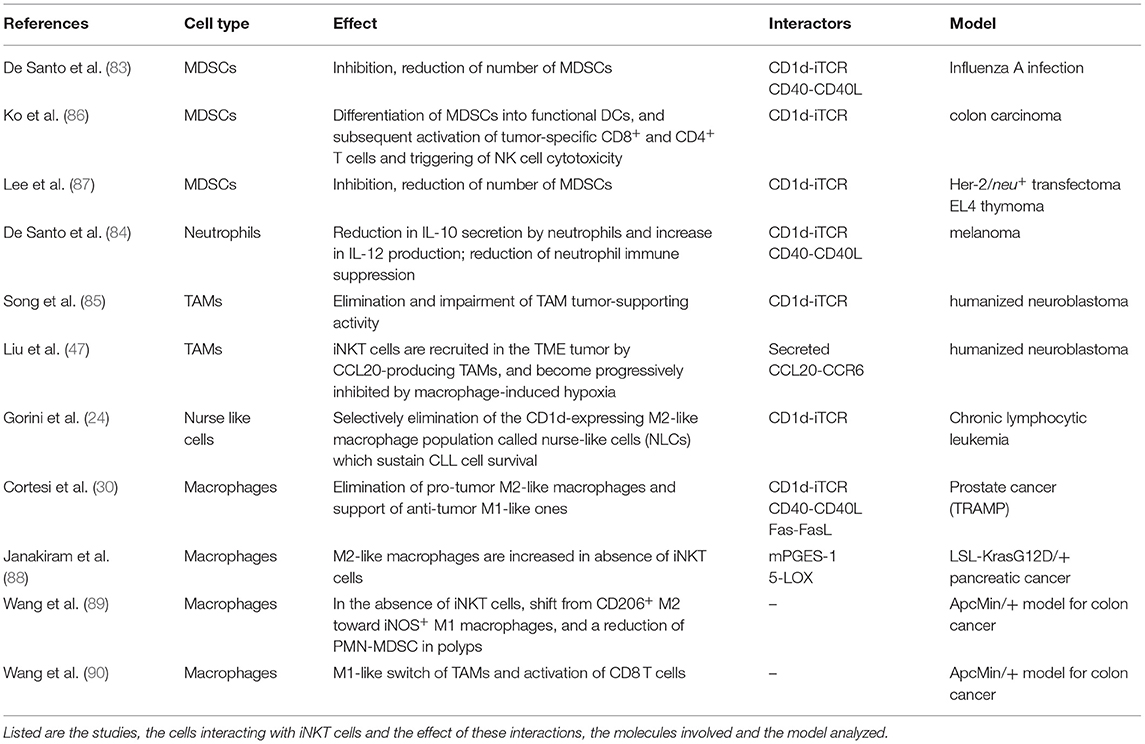

Despite their low numbers, iNKT cells are normal components of both mouse and human TMEs (24, 34, 47, 55), where they can efficiently reprogram tumor opposing state irrespectively of the CD1d expression by cancer cells, by restraining the immunosuppressive functions of myelomonocytic cells such as TAMs, MDSC and TANs populations (83–85), as summarized in Table 1.

iNKT cells were first shown to inhibit MDSCs suppressive activity in a model of influenza A viral infection in a CD1d- and CD40- dependent manner (83). Several evidence support this ability also in cancer. iNKT cells promote the differentiation of MDSCs into functional DCs upon α-GalCer injection in a mouse model of colon carcinoma, leading to the activation of tumor-specific CD8+ and CD4+ T cells and the triggering of NK cell cytotoxicity (86). iNKT cells also reduce CD1d+ MDSCs numbers and activity (83, 87) enhancing the conversion of immature MDSCs to mature APCs (83, 86). In particular, in human melanoma patients, iNKT cells could also reverse the immune-suppressive activity of a population of neutrophils producing IL-10, by inducing their maturation toward IL-12-producing cells via CD1d- and CD40- interactions, ultimately reinstating the activation of tumor antigen-specific CD8+ T cells (84). These iNKT cell anti-tumor effector functions on immunosuppressive myelomonocytic cells in the TME are exerted by CD1d-cognate recognition. Observations in a humanized neuroblastoma mouse model highlight the elimination by the transferred human iNKT cells of CD1d-expressing TAMs, impairing their tumor-supporting activity (85). The importance of the iNKT cell-TAM crosstalk is further strengthened in the same humanized neuroblastoma model, by showing that iNKT cells are recruited in the TME tumor by CCL20-producing TAMs, but are progressively inhibited in their anti-tumor activity by macrophage-induced hypoxia (47). Notably, iNKT cells can discriminate between anti-tumor M1-like cells and pro-tumor M2-like ones, selectively eliminating pro-tumor M2-like macrophages while supporting anti-tumor M1-like populations (24, 30). For instance, in a model of oncogene-induced pancreatic cancer, M2-like macrophages are increased in absence of iNKT cells, suggesting the preferential targeting of this pro-tumor macrophage population by iNKT cells (88). By investigating at the same time a transgenic mouse model of CLL and patients with stable or progressive disease, we showed that iNKT cells delay the onset and progression of the leukemia by remodeling the supporting niche of the leukemia cells through the selective elimination of the CD1d-expressing M2-like macrophage population called nurse-like cells (NLCs) (24), which sustain CLL cell survival (24, 91). Furthermore, we have found that iNKT cells selectively restrict M2-like TAMs in the TME, delaying the progression of an autochthonous TRAMP mouse prostate adenocarcinoma model, while in human prostate cancer the disease aggressiveness correlates with reduced intra-tumor iNKT cells and increased M2 macrophages, underscoring the clinical significance of this crosstalk (30). Adoptively transferred iNKT cells were able to infiltrate the TME of TRAMP mice and selectively kill M2-like TAMs upon CD1d-stimulation and the combinatorial engagement of CD40 and Fas. Although both molecules are expressed to similar levels on either M1-like or M2-like TAM populations, in vitro co-culture experiments between mouse iNKT cells and M1- or M2- bone marrow-derived monocytes revealed that the CD40L-CD40 pathway support the selective survival of the M1 population, by antagonizing the apoptotic death driven by Fas signaling. By contrast, CD40 expression did not protect M2 cells from FAS-dependent killing, suggesting that CD40 engagement may transduce distinct intracellular signals between M1 and M2 macrophages. Interestingly, the iNKT ability to promote immunostimulatory Th1/M1-like conditions in the TME seems to be context-dependent. In fact, iNKT cells naturally promote the formation of polyps in the spontaneous murine adenomatous polyposis coli (Apc) ApcMin/+ model for colon cancer (89), associated with a shift from M1-like to M2-like TAMs and decreased pro-inflammatory/ TH1 associated gene expression, which were reverted in ApcMin/+ mice lacking iNKT cells (89). However, the treatment of ApcMin/+ mice with strong iNKT cell agonists (α-GalCer and C20:2) reduced the polyp size in the small intestine thanks to iNKT cell-dependent intra-tumor activation of CD8 T cells and M1-like switch of TAMs (90). Yet, iNKT cells showed reduced frequencies and PD-1 upregulation (90), suggesting an anergic state for iNKT cells in α-GalCer-treated mice (92, 93). Consistently, the addition of PD-1 blockade improved the treatment with the iNKT cell agonist α-GalCer and enhance anti-tumor activities, resulting in highly significant reduction of polyp numbers in the small and large intestine, maintenance of iNKT cells and a skew toward a TH1-like iNKT1 phenotype specifically in polyps (94). The dichotomous iNKT cell response in the different tumors may be related to changes undergoing in the TME: in healthy intestine NKT1 and NKT17 subsets are mostly represented, whereas as tumor progresses iNKT cells infiltrating intestinal polyps start to produce IL-10 (77).

Nevertheless, while on the one hand iNKT cells are emerging as potent mediators of cancer immune surveillance, on the other hand several mechanisms of tumor immune evasion from iNKT cell control are becoming increasingly clear. For instance, tumors can elicit the upregulating the inhibitory NK receptor Ly49C/F/H/I causing iNKT cell unresponsiveness, as reported in the TRAMP murine model (55). Of note, this dysfunctional iNKT cell phenotype could be rescued in vitro by simultaneous stimulation with α-GalCer and IL-12, which likely overrides the inhibitory signal. Furthermore, likewise T cells, also tumor-unresponsive iNKT cells were reported to express PD-1, and their responsiveness could be reverted by PD-1/PD-L1 blockade (93). Finally, additional mechanisms related to intra-tumor metabolic dysregulation, hypoxia or accumulation of toxic products could play a role in the induction of iNKT cell dysfunctions (95, 96). All these suppressive mechanisms impact the iNKT cell counts and TH1 cytokines production in patients with late-stage progressive disease and must be kept in mind for potential therapeutic applications.

Collectively, these data show that iNKT cells exert their main anti-tumor functions by primarily modulating different myelomonocytic cell populations in the TME.

iNKT Cell Are Highly Suitable for Adoptive Immunotherapy of Cancer

Given that immunosuppressive cues derived from the TME represent the major hurdle that must be overcome by the current adoptive cell therapy strategies to become efficient, particularly in solid tumors (97, 98), the peculiar ability of iNKT cells to reprogram immunostimulatory conditions in the TME could be actively exploited to enhance the efficacy of the approach. Furthermore, iNKT cells possess other unique features that make them particularly suitable for adoptive immunotherapy of cancer. First, they are restricted for the monomorphic CD1d molecule, which is identical in all individuals permitting their functions across MHC barriers without risks of alloreactivity (99). Whereas not relevant in the autologous immunotherapy setting, GvHD is the major concern for adoptive cell therapy with allogeneic T cells, which are restricted for the polymorphic MHC molecules, and can give raise to alloreactive anti-host response by donor T cells. By contrast, iNKT cells have been shown in pre-clinical models to suppress GvHD and are associated with reduced GvHD in the clinic. Several studies have reported that GvHD is exacerbated in CD1d−/− or Jα18−/− mice and that stimulation of iNKT cells can increase anti-leukemia responses while simultaneously mitigating the severity of GvHD (100). Interestingly, in the context of hematopoietic stem cell (HSC) transplantation, preclinical and clinical studies demonstrate that iNKT cells significantly attenuate GvHD without abrogating the graft vs. leukemia (GvL) effect, exerted through direct and indirect mechanisms (99, 101–103). In pediatric acute leukemia patients, this process has been correlated with the engraftment of donor iNKT cells, as failure to reconstitute iNKT cells after transplantation strongly correlates with disease relapse (40). Studies into the mechanisms of GvHD suppression showed that iNKT cells modulate the overall grafted immune response through production of TH2 cytokines such as IL-4, which restrains inflammatory donor T cells, and promote Treg proliferation against both acute and chronic GvHD (103). Adoptively transferred iNKT cells are at least 10 times more potent than Tregs in protecting mice from lethal GvHD without compromising the GvL effect (104). iNKT cells have the unique ability to secrete both TH1 and TH2 cytokines, in particular human CD4+ iNKT cells are able to secrete IL-4 and IL-13 whereas DN iNKT cells were able to secrete TH1 cytokines (15). Thus, TH2 iNKT cells facilitate the engraftment of allogenic donor cells against recurrence of leukemia, while the TH1 arm generate antitumor response (105).

Because of the lack of toxicity in the allogeneic setting, iNKT cells seem the ideal platform for the generation of “off-the-shelf” ready-to-use effector cells for adoptive immunotherapy of cancer. Nevertheless, allogeneic iNKT cells must be somewhat edited to downregulate their MHC expression to avoid a possible rejection mediated by the allogeneic host immune system. To this purpose, iNKT cells have been differentiated in vitro from human hematopoietic stem cells that express very low levels of HLA-I and almost undetectable HLA-II molecules, which then can be further engineered with CARs to generate stealth anti-tumor effectors for the host immune response (106). An alternative strategy to generate off-the-shelf allogeneic iNKT cells, currently being assessed in early phase clinical trials for patients with progressing B cell malignancies (ANCHOR NCT03774654), relies in the co-expression of CD19-CAR, IL-15, and shRNAs targeting beta-2 microglobulin and CD74 to downregulate surface HLA class I and class II molecules. Although the strategy, which is combined by the lymphodepletion of the recipients before iNKT cell transfer, shows promise, it should be kept in mind that the complete abrogation of MHC expression on the transferred allogeneic cells should trigger the “missing self” response by NK cells, ultimately eliminating the gene-edited iNKT cells. This may be mitigated by engineering the allogeneic tumor-redirected HLA-edited effectors to express ligands for the NK inhibitory receptors (107) or the “don't eat me signal” provided by CD47 to prevent phagocytosis by phagocytes (108), which can cooperate to promote long term effects of the adoptive cell therapy.

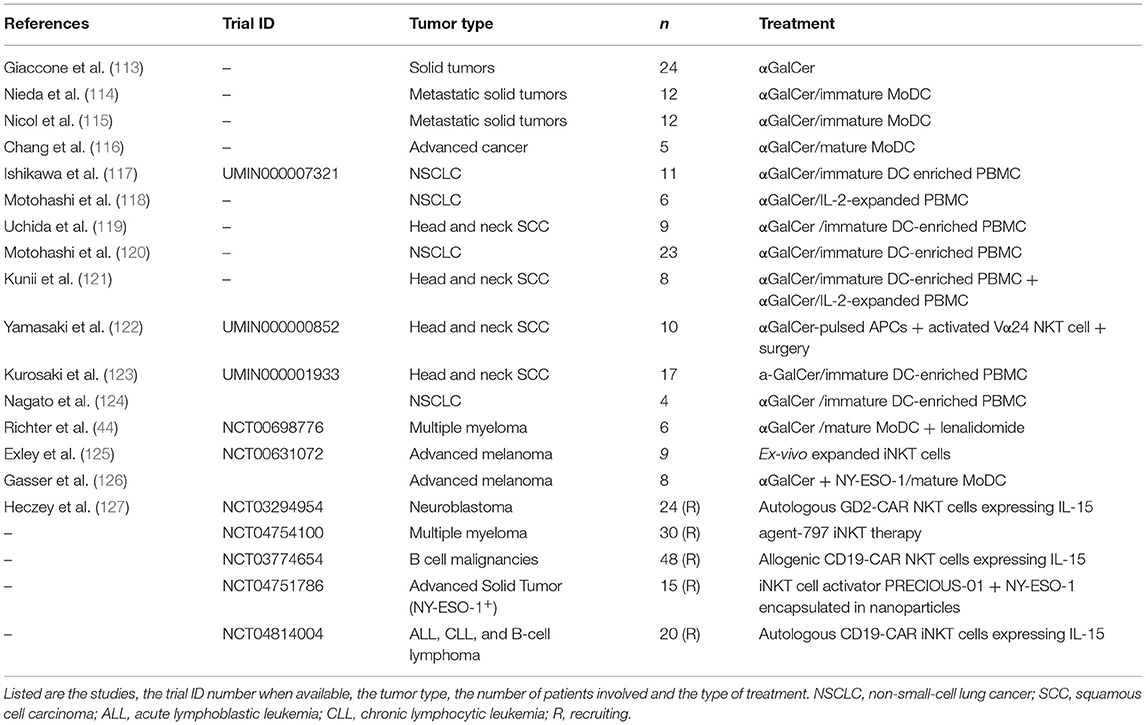

A possible pitfall for adoptive iNKT cell immunotherapy is that the median frequency of these cells in the human peripheral blood is 0.01% in most individuals and decreases further in advanced cancer patients. However, iNKT cells easily expand in culture and efficient protocols to activate and expand iNKT cells from the patients have been established (109). Considering the lack of histocompatibility barriers for iNKT cell functions, allogenic donor source could also be an intriguing experimental alternative. To overcome the issue, concerning the generation of a huge number of iNKT cells in vitro for clinical purpose, Taniguchi and colleagues developed an interesting strategy based on induced-pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) technology. They were able to derive iPSCs from mouse splenic iNKT cells and to induce such high proliferative stem cells to differentiate into functional iNKT cells in vitro. The iPSC-derived iNKT cells recapitulated the adjuvant effects of physiologic iNKT cells and suppressed tumor growth in vivo (110). The same results were also obtained with human iPSC-derived iNKT cells, which could be activated by α-GalCer-pulsed DCs and produced as much IFNγ as natural parental cells but exhibited better cytotoxic activity against various tumor cell lines. iPSC-derived iNKT cells also possessed significant anti-tumor activity in tumor-bearing mice (111). In a recent work iNKT cells were also generated from human CD34+ HSC engineered to express the rearranged TCR genes from a iNKT cell clone (112). This study showed that HSC-iNKT cells have the expected properties of human iNKT cells in terms of their distribution, phenotype, and ability to secrete cytokines in a bone-marrow-liver-thymus (BLT) humanized mouse model. Moreover, in vivo HSC-iNKT cells could also protect against a multiple myeloma or a melanoma that expressed CD1d, without the requirement of α-GalCer, by the recognition of tumor-endogenous lipid antigens. iNKT cells have been actively exploited in several clinical studies, summarized in Table 2 (44, 106–113, 126).

In conclusion, iNKT cells are an attractive novel alternative to conventional T cells for cancer immunotherapy. Their CD1d restriction, tumor tissue tropism, ability to restrict the suppressive TME support their exploitation for advanced adoptive cell therapy to treat solid and hematological malignancies.

iNKT Cells can be Engineered to Acquire a Second Antigen-Specificity

iNKT cells exert their anti-tumor effector functions by modulating in a CD1d-cognate recognition manner immunosuppressive myelomonocytic cells infiltrating the TME. Hence, considering the increased use of CAR- or TCR-engineered cells for adoptive cell therapy, it is likely that allogenic iNKT cells could be exploited as single effector for the dual targeting of cancer cells and suppressive tumor stroma, which is considered a critical factor for the efficacy of any adoptive cell therapy strategy. This approach implies that iNKT cells must utilize both their endogenous TCR and the exogenous tumor-specific CAR/TCR, unlike conventional T cells, in which the current tendency is to eliminate the expression of the endogenous TCRs to maximize the function of the transduced receptors. In fact, in an autologous setting, the endogenous TCRs expressed by a bulk polyclonal T cell preparations are unlikely to contribute to anti-tumor effects, while in an allogeneic setting, these TCRs would instead cause GvHD. Moreover, the expression of the endogenous TCR by CAR/TCR transduced iNKT cells provide another advantage over T cells, which is the ability to boosting their combinatorial anti-tumor functions with α-GalCer (or other agonists) in vivo and enhance the overall therapeutic effect of the engineered iNKT cells (128).

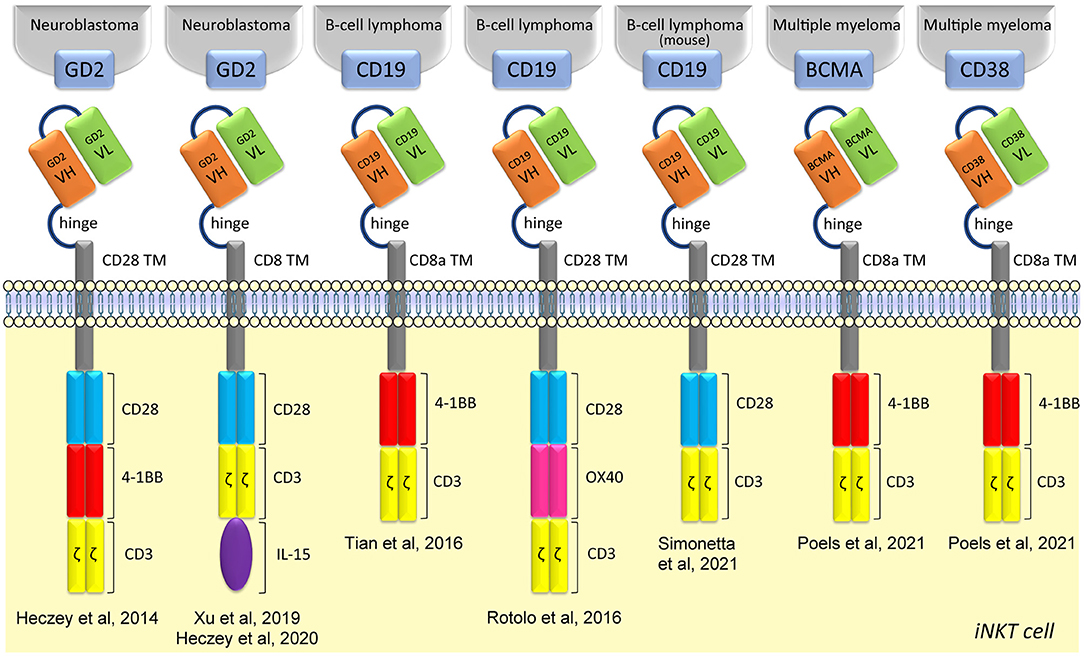

CAR therapies were first applied using conventional T cells, granting the approval by the Food and Drug Administration of two CAR-T cell therapies for acute lymphoblastic leukemia and for advanced lymphoma. Human iNKT cells can also be efficiently engineered to express GD2 CARs (against neuroblastomas), CD19 CARs (against B cell lymphomas), and CD38 or BCMA CARs (against multiple myeloma) (129–132), depicted in Figure 1. CAR-iNKT cells kill their relevant antigen-expressing tumor cell lines or patient-derived plasma cells in vitro (129–132) and tumor xenograft models in vivo (129–131), maintaining their CD1d-dependent functions. The lytic ability of CAR-iNKT cells appears independent of the costimulatory domain inserted in the CAR, whereas the CARs containing the 4-1BB domain seems to promote a better expansion capacity (132). GD2-CAR-iNKT cells persistence and anti-tumor activity can be further increased wit CAR constructs co-expressing human IL-15 (133), while increasing the expression of CD1d on B-lymphoma or leukemia cells with epigenetic drugs substantially enhanced their targeting by CD19-CAR-iNKT cells, resulting in markedly improved cancer control in mouse xenograft models (131). Notably, in this way, intravenously administered CAR19- iNKT but not CAR19-T-cells swiftly eradicated secondary brain lymphoma (131). Furthermore, in an immunocompetent mouse model of syngeneic B-cell lymphoma, CD19-CAR-iNKT cells exerted potent direct cancer cell killing and were also able to recruit host tumor-specific CD8 T-cell responses via facilitating tumor-antigen cross-priming, in turn enhancing long term cancer control (134). Phase I clinical trials with CAR-iNKT cells already showed promising results, in an interim analysis on children with relapsed or resistant neuroblastoma treated with autologous iNKT cells engineered to co-express a GD2-CAR with IL-15 (NCT03294954) (127). First, no dose-limiting toxicities were observed. Second, CAR-iNKT cells expanded in vivo, actively localized to tumor masses and, in one out of three patients, induced regression of bone metastatic lesions. Other two phase I clinical trials are exploring whether donor-derived or allogenic-(NCT03774654 and NCT04814004, respectively) iNKT cells transduced with CAR19 might help in patients with CD19+ lymphoma or leukemia.

Figure 1. Structure of CAR iNKT-cells. CAR iNKT-cells are composed of several parts: an extracellular single-chain variable fragment (scFv), a hinge for flexibility and distance, a transmembrane spacer, different intracellular costimulatory molecules, and TCR CD3ζ subunit.

iNKT cells can be also engineered to acquire a second antigen-specificity by expressing recombinant TCRs that recognize pathology relevant antigens and, in particular, tumor associated antigens. For instance, the transfer a human MHC-I restricted TCR specific for a peptide epitope derived from the Mycobacterium tuberculosis (Mtb) 38-kDa protein generated iNKT cells able to specifically kill Mo-DCs pre-loaded with the 38-kDa protein. The same TCR-engineered iNKT cells maintained the recognition of α-GalCer-pulsed Mo-DCs, suggesting that the endogenous iTCR was still fully functional (135). Human iNKT cells were also efficiently redirected against melanoma cell lines by engineering with a high affinity TCRs specific for an HLA-2-restricted peptide epitope derived from the tumor associated antigens (MART-126−35, PRAME, Survin96−104). The TCR-iNKT cells efficiently killed antigen expressing melanoma cells in vitro and showed HLA-restricted antitumor activity in xenogeneic mouse models (136). However, in this study the iNKT cell endogenous TCR was completely displaced from the cell surface by the transferred TCRs, thus thwarting all the natural antitumor functions of iNKT cells. To overcome this limitation, there are several strategies that can be borrowed from TCR transfer in T cells to avoid the displacement of iNKT cell endogenous TCR, like modifications facilitating intramolecular bonding between transgenic α and β chains, fusing the chains to CD3ζ (137). Implementation of these strategies also for TCR transfer in iNKT cells will enable the generation of tumor retargeted cells which maintain, at the same time, the peculiar iNKT cells capacity of TME remodeling, having enhanced anti-tumor activities.

Notwithstanding all the above advantages of exploiting iNKT cell engineering for adoptive cell therapy of cancer, there also possible concerns connected with their use, for instance considering the prompt and abundant secretion of different cytokines by iNKT cells. The potent cytokine response produced by CAR-T cells upon target recognition in vivo is in fact responsible for the serious acute systemic toxicity (particularly neurological) often observed in treated patients. We currently do not know whether this side effect may reduce, or increase, when using CAR-iNKT cells. A recent study reported that iNKT cells transiently expressing a RNA-based anti-CSPG4 CAR produced much lower quantities of IL-6 and other cytokines involved in cytokine release syndrome (i.e., TNF and IFNγ) than the CAR-transfected CD8+ T cells, even if they have equal specific cytotoxicity (138). Nevertheless, the results of the ongoing CAR-iNKT cell clinical trials will clarify the actual safety and toxicity profiles of this approach, compared to CAR-T cells.

CAR- and TCR-iNKT cells therefore represent a potential new generation of dual-specific effector cells that warrant additional investigation to assess their anti-tumor efficacy in adoptive cell therapy, compared to T cells. This paves the way for advanced cell therapies in cancer patients, free from the concerns for HLA matching and possibly exploiting a redirected specificity toward tumor associated antigens combined with the TME remodeling exerted by the unique iNKT cell population.

Author Contributions

GD, PD, GC, and MF selected the review topic, collected relevant publications, and wrote the review. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

The study was funded by a FIRC-AIRC Fellowship Number 2019-22604 to GD, Grants from Fondazione Cariplo 2018-0366 to MF, Worldwide Cancer Research 19-0133 to GD, Associazione Italiana Ricerca sul Cancro (AIRC) IG2017-ID.20081 to GC, Italian Healthy Ministry project on CAR T RCR-2019-23669115 to GC and PD, and Fondazione AIRC under-5-per-Mille 2019-ID.22737 to PD.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1. Yankelevich B, Knobloch C, Nowicki M, Dennert G. A novel cell type responsible for marrow graft rejection in mice. T cells with NK phenotype cause acute rejection of marrow grafts. J Immunol. (1989) 142:3423–30.

2. Sykes M. Unusual T cell populations in adult murine bone marrow. Prevalence of CD3+CD4-CD8- and alpha beta TCR+NK11+ cells. J Immunol. (1990) 145:3209–15.

3. Ballas ZK. Rasmussen W. NK11+ thymocytes Adult murine CD4-, CD8- thymocytes contain an NK11+, CD3+, CD5hi, CD44hi, TCR-V beta 8+ subset. J Immunol. (1990) 145:1039–45.

4. Lantz O, Bendelac A. An invariant T cell receptor alpha chain is used by a unique subset of major histocompatibility complex class I-specific CD4+ and CD4-8- T cells in mice and humans. J Exp Med. (1994) 180:1097–106. doi: 10.1084/jem.180.3.1097

5. Dellabona P, Padovan E, Casorati G, Brockhaus M, Lanzavecchia A. An invariant V alpha 24-J alpha Q/V beta 11 T cell receptor is expressed in all individuals by clonally expanded CD4-8- T cells. J Exp Med. (1994) 180:1171–6. doi: 10.1084/jem.180.3.1171

6. Bendelac A, Savage PB, Teyton L. The biology of NKT cells. Annu Rev Immunol. (2007) 25:297–336. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.25.022106.141711

7. Brennan PJ, Brigl M, Brenner MB. Invariant natural killer T cells: an innate activation scheme linked to diverse effector functions. Nat Rev Immunol. (2013) 13:101–17. doi: 10.1038/nri3369

8. Kawano T, Cui J, Koezuka Y, Toura I, Kaneko Y, Motoki K, et al. CD1d-restricted and TCR-mediated activation of valpha14 NKT cells by glycosylceramides. Science. (1997) 278:1626–9. doi: 10.1126/science.278.5343.1626

9. Cohen NR, Garg S, Brenner MB. Antigen Presentation by CD1 Lipids, T Cells, and NKT Cells in microbial immunity. Adv Immunol. (2009) 102:1–94. doi: 10.1016/S0065-27760901201-2

10. Bendelac A, Bonneville M, Kearney JF. Autoreactivity by design: innate B and T lymphocytes. Nat Rev Immunol. (2001) 1:177–86. doi: 10.1038/35105052

11. Kain L, Webb B, Anderson BL, Deng S, Holt M, Costanzo A, et al. The identification of the endogenous ligands of natural killer T cells reveals the presence of mammalian α-linked glycosylceramides. Immunity. (2014) 41:543–54. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2014.08.017

12. Govindarajan S, Verheugen E, Venken K, Gaublomme D, Maelegheer M, Cloots E, et al. ER stress in antigen-presenting cells promotes NKT cell activation through endogenous neutral lipids. EMBO Rep. (2020) 21:e48927. doi: 10.15252/embr.201948927

13. Bedard M, Shrestha D, Priestman DA, Wang Y, Schneider F, Matute JD, et al. Sterile activation of invariant natural killer T cells by ER-stressed antigen-presenting cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. (2019) 116:23671–81. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1910097116

14. Crosby CM, Kronenberg M. Tissue-specific functions of invariant natural killer T cells. Nat Rev Immunol. (2018) 18:559–74. doi: 10.1038/s41577-018-0034-2

15. Lee PT, Benlagha K, Teyton L, Bendelac A. Distinct functional lineages of human Vα24 natural killer T cells. J Exp Med. (2002) 195:637–41. doi: 10.1084/jem.20011908

16. Cui J, Shin T, Kawano T, Sato H, Kondo E, Toura I, et al. Requirement for V α 14 NKT Cells in IL-12-mediated rejection of tumors. Science (80-). (1997) 278:1623–6. doi: 10.1126/science.278.5343.1623

17. Morita M, Motoki K, Akimoto K, Natori T, Sakai T, Sawa E, et al. Structure-activity relationship of alpha-galactosylceramides against B16-bearing mice. J Med Chem. (1995) 38:2176–87.

18. Toura I, Kawano T, Akutsu Y, Nakayama T, Ochiai T, Taniguchi M. Cutting edge: inhibition of experimental tumor metastasis by dendritic cells pulsed with alpha-galactosylceramide. J Immunol. (1999) 163:2387–91.

19. Nakui M, Ohta A, Sekimoto M, Sato M, Iwakabe K, Yahata T, et al. Potentiation of antitumor effect of NKT cell ligand, α-galactosylceramide by combination with IL-12 on lung metastasis of malignant melanoma cells. Clin Exp Metastasis. (2000) 18:147–53. doi: 10.1023/A:1006715221088

20. Smyth MJ, Crowe NY, Pellicci DG, Kyparissoudis K, Kelly JM, Takeda K, et al. Godfrey DI. Sequential production of interferon-γ by NK11+ T cells and natural killer cells is essential for the antimetastatic effect of α-galactosylceramide. Blood. (2002) 99:1259–66. doi: 10.1182/blood.V99.4.1259

21. Hayakawa Y, Rovero S, Forni G, Smyth MJ. Alpha-galactosylceramide (KRN7000) suppression of chemical- and oncogene-dependent carcinogenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. (2003) 100:9464–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1630663100

22. Gebremeskel S, Clattenburg DR, Slauenwhite D, Lobert L, Johnston B. Natural killer T cell activation overcomes immunosuppression to enhance clearance of postsurgical breast cancer metastasis in mice. Oncoimmunology. (2015) 4:1–11. doi: 10.1080/2162402X.2014.995562

23. Crowe NY, Coquet JM, Berzins SP, Kyparissoudis K, Keating R, Pellicci DG, et al. Differential antitumor immunity mediated by NKT cell subsets in vivo. J Exp Med. (2005) 202:1279–88. doi: 10.1084/jem.20050953

24. Gorini F, Azzimonti L, Delfanti G, Scarfo L, Scielzo C, Bertilaccio MT, et al. Invariant NKT cells contribute to chronic lymphocytic leukemia surveillance and prognosis. Blood. (2017) 129:65. doi: 10.1182/blood-2016-11-751065

25. Renukaradhya GJ, Khan MA, Vieira M, Du W, Gervay-Hague J, Brutkiewicz RR. Type I NKT cells protect (and type II NKT cells suppress) the host's innate antitumor immune response to a B-cell lymphoma. Blood. (2008) 111:5637–45. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-05-092866

26. Swann JB, Uldrich AP, van Dommelen S, Sharkey J, Murray WK, Godfrey DI, et al. Type I natural killer T cells suppress tumors caused by p53 loss in mice. Blood. (2009) 113:6382–5. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-01-198564

27. Bellone M, Ceccon M, Grioni M, Jachetti E, Calcinotto A, Napolitano A, et al. cells control mouse spontaneous carcinoma independently of tumor-specific cytotoxic T cells. PLoS ONE. (2010) 5:e8646. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0008646

28. Bassiri H, Das R, Guan P, Barrett DM, Brennan PJ, Banerjee PP, et al. iNKT cell cytotoxic responses control T-lymphoma growth in vitro and in vivo. Cancer Immunol Res. (2014) 2:59–69. doi: 10.1158/2326-6066.CIR-13-0104

29. Crowe NY, Smyth MJ, Godfrey DI. A critical role for natural killer T cells in immunosurveillance of methylcholanthrene-induced sarcomas. J Exp Med. (2002) 196:119–27.

30. Cortesi F, Delfanti G, Grilli A, Calcinotto A, Gorini F, Pucci F, et al. Bimodal CD40/Fas-dependent crosstalk between iNKT cells and tumor-associated macrophages impairs prostate cancer progression. Cell Rep. (2018) 22:3006–20. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2018.02.058

31. Molling JW, Kölgen W, Van Der Vliet HJJ, Boomsma MF, Kruizenga H, Smorenburg CH, et al. Peripheral blood IFN-γ-secreting Vα24+Vβ11 + NKT cell numbers are decreased in cancer patients independent of tumor type or tumor load. Int J Cancer. (2005) 116:87–93. doi: 10.1002/ijc.20998

32. Fujii S-I, Shimizu K, Smith C, Bonifaz L, Steinman RM. Activation of natural killer T cells by alpha-galactosylceramide rapidly induces the full maturation of dendritic cells in vivo and thereby acts as an adjuvant for combined CD4 and CD8 T cell immunity to a coadministered protein. J Exp Med. (2003) 198:267–79. doi: 10.1084/jem.20030324

33. Molling JW, Langius J a. E, Langendijk J a, Leemans CR, Bontkes HJ, van der Vliet HJJ, et al. Low levels of circulating invariant natural killer T cells predict poor clinical outcome in patients with head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. J Clin Oncol. (2007) 25:862–8. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.08.5787

34. Metelitsa LS, Wu HW, Wang H, Yang Y, Warsi Z, Asgharzadeh S, et al. Natural killer T cells infiltrate neuroblastomas expressing the chemokine CCL2. J Exp Med. (2004) 199:1213–21. doi: 10.1084/jem.20031462

35. Najera Chuc AE, Cervantes LAM, Retiguin FP, Ojeda JV, Maldonado ER. Low number of invariant NKT cells is associated with poor survival in acute myeloid leukemia. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. (2012) 138:1427–32. doi: 10.1007/s00432-012-1251-x

36. Tachibana T, Onodera H, Tsuruyama T, Mori A, Nagayama S, Hiai H, et al. Increased intratumor Valpha24-positive natural killer T cells: a prognostic factor for primary colorectal carcinomas. Clin Cancer Res. (2005) 11:7322–7. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-0877

37. Hishiki T, Mise N, Harada K, Ihara F, Takami M, Saito T, et al. Invariant natural killer T infiltration in neuroblastoma with favorable outcome. Pediatr Surg Int. (2018) 34:195–201. doi: 10.1007/s00383-017-4189-x

38. Lundgren S, Warfvinge CF, Elebro J, Heby M, Nodin B, Krzyzanowska A, et al. The Prognostic Impact of NK/NKT Cell Density in Periampullary Adenocarcinoma Differs by Morphological Type and Adjuvant Treatment. PLoS One. (2016) 11:e0156497. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0156497

39. Shaulov A, Yue S, Wang R, Joyce RM, Balk SP, Kim HT, et al. Peripheral blood progenitor cell product contains Th1-biased non-invariant CD1d-reactive natural killer T cells: implications for posttransplant survival. Exp Hematol. (2008) 36:464–72. doi: 10.1016/j.exphem.2007.12.010

40. de Lalla C, Rinaldi A, Montagna D, Azzimonti L, Bernardo ME, Sangalli LM, et al. Invariant NKT cell reconstitution in pediatric leukemia patients given HLA-haploidentical stem cell transplantation defines distinct CD4+ and CD4- subset dynamics and correlates with remission state. J Immunol. (2011) 186:4490–9. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1003748

41. Tahir SM, Cheng O. Shaulov a, Koezuka Y, Bubley GJ, Wilson SB, Balk SP, Exley M. Loss of IFN-gamma production by invariant NK T cells in advanced cancer. J Immunol. (2001) 167:4046–50. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.167.7.4046

42. Singh AK, Shukla NK, Das SN. Altered Invariant Natural Killer T cell Subsets and its functions in patients with oral squamous cell carcinoma. Scand J Immunol. (2013) 78:468–77. doi: 10.1111/sji.12104

43. Dhodapkar M V, Geller MD, Chang DH, Shimizu K, Fujii S-I, Dhodapkar KM, et al. reversible defect in natural killer T cell function characterizes the progression of premalignant to malignant multiple myeloma. J Exp Med. (2003) 197:1667–76. doi: 10.1084/jem.20021650

44. Richter J, Neparidze N, Zhang L, Nair S, Monesmith T, Sundaram R, et al. Clinical regressions and broad immune activation following combination therapy targeting human NKT cells in myeloma. Blood. (2013) 121:423–30. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-06-435503

45. Metelitsa LS. Anti-tumor potential of type-I NKT cells against CD1d-positive and CD1d-negative tumors in humans. Clin Immunol. (2011) 140:119–29. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2010.10.005

46. Song L, Ara T, Wu H-W, Woo C-W, Reynolds CP, Seeger RC, et al. Oncogene MYCN regulates localization of NKT cells to the site of disease in neuroblastoma. J Clin Invest. (2007) 117:2702–12. doi: 10.1172/JCI30751

47. Liu D, Song L, Wei J, Courtney AN, Gao X, Marinova E, et al. IL-15 protects NKT cells from inhibition by tumor-associated macrophages and enhances antimetastatic activity. J Clin Invest. (2012) 122:2221–33. doi: 10.1172/JCI59535

48. Metelitsa LS, Weinberg KI, Emanuel PD, Seeger RC. Expression of CD1d by myelomonocytic leukemias provides a target for cytotoxic NKT cells. Leukemia. (2003) 17:1068–77. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2402943

49. Nieda M, Nicol A, Koezuka Y, Kikuchi A, Lapteva N, Tanaka Y, et al. TRAIL expression by activated human CD4+Vα24NKT cells induces in vitro and in vivo apoptosis of human acute myeloid leukemia cells. Blood. (2001) 97:2067–74. doi: 10.1182/blood.V97.7.2067

50. Dao T, Mehal WZ, Crispe IN. IL-18 augments perforin-dependent cytotoxicity of liver NK-T cells. J Immunol. (1998) 161:2217–22.

51. Wingender G, Krebs P, Beutler B, Kronenberg M. Antigen-specific cytotoxicity by invariant NKT cells in vivo is CD95/CD178-dependent and is correlated with antigenic potency. J Immunol. (2010) 185:2721–9. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1001018

52. Wu DY, Segal NH, Sidobre S, Kronenberg M, Chapman PB. Cross-presentation of disialoganglioside GD3 to natural killer T cells. J Exp Med. (2003) 198:173–81. doi: 10.1084/jem.20030446

53. Liu D, Song L, Brawley VS, Robison N, Wei J, Gao X, et al. Medulloblastoma expresses CD1d and can be targeted for immunotherapy with NKT cells. Clin Immunol. (2013) 149:55–64. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2013.06.005

54. Chong TW, Goh FY, Sim MY, Huang HH, Thike DAA, Lim WK, et al. CD1d expression in renal cell carcinoma is associated with higher relapse rates, poorer cancer-specific and overall survival. J Clin Pathol. (2015) 68:200–5. doi: 10.1136/jclinpath-2014-202735

55. Nowak M, Arredouani MS, Tun-Kyi A, Schmidt-Wolf I, Sanda MG, Balk SP, et al. Defective NKT cell activation by CD1d+ TRAMP prostate tumor cells is corrected by interleukin-12 with α-galactosylceramide. PLoS One. (2010) 5:e11311. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0011311

56. Miura S, Kawana K, Schust DJ, Fujii T, Yokoyama T, Iwasawa Y, et al. CD1d, a sentinel molecule bridging innate and adaptive immunity, is downregulated by the human papillomavirus (HPV) E5 protein: a possible mechanism for immune evasion by HPV. J Virol. (2010) 84:11614–23. doi: 10.1128/jvi.01053-10

57. Yang PM, Lin PJ, Chen CC. CD1d induction in solid tumor cells by histone deacetylase inhibitors through inhibition of HDAC1/2 and activation of Sp1. Epigenetics. (2012) 7:390–9. doi: 10.4161/epi.19373

58. Díaz-Basabe A, Burrello C, Lattanzi G, Botti F, Carrara A, Cassinotti E, et al. Human intestinal and circulating invariant natural killer T cells are cytotoxic against colorectal cancer cells via the perforin–granzyme pathway. Mol Oncol. (2021) 15:3385–403. doi: 10.1002/1878-0261.13104

59. Hermans IF, Silk JD, Gileadi U, Salio M, Mathew B, Ritter G, et al. cells enhance CD4+ and CD8+ T cell responses to soluble antigen in vivo through direct interaction with dendritic cells. J Immunol. (2003) 171:5140−7. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.10.5140

60. Binnewies M, Roberts EW, Kersten K, Chan V, Fearon DF, Merad M, et al. Understanding the tumor immune microenvironment (TIME) for effective therapy. Nat Med. (2018) 24:541–50. doi: 10.1038/s41591-018-0014-x

61. Awad RM, De Vlaeminck Y, Maebe J, Goyvaerts C, Breckpot K. Turn Back the TIMe: targeting tumor infiltrating myeloid cells to revert cancer progression. Front Immunol. (2018) 9:1977. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2018.01977

62. Scott EN, Gocher AM, Workman CJ, Vignali DAA. Regulatory T cells: barriers of immune infiltration into the tumor microenvironment. Front Immunol. (2021) 12:702726. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2021.702726

63. Qin Z, Richter G, Schüler T, Ibe S, Cao X, Blankenstein T, et al. cells inhibit induction of T cell-dependent tumor immunity. Nat Med. (1998) 4:627–30. doi: 10.1038/nm0598-627

64. Schioppa T, Moore R, Thompson RG, Rosser EC, Kulbe H, Nedospasov S, et al. regulatory cells and the tumor-promoting actions of TNF-α during squamous carcinogenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. (2011) 108:10662–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1100994108

65. Solinas G, Germano G, Mantovani A, Allavena P. Tumor-associated macrophages (TAM) as major players of the cancer-related inflammation. J Leukoc Biol. (2009) 86:1065–73. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0609385

66. Broz ML, Krummel MF. The emerging understanding of myeloid cells as partners and targets in tumor rejection. Cancer Immunol Res. (2015) 3:313–9. doi: 10.1158/2326-6066.CIR-15-0041

67. Allavena P, Sica A, Garlanda C, Mantovani A. The Yin-Yang of tumor-associated macrophages in neoplastic progression and immune surveillance. Immunol Rev. (2008) 222:155–61. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2008.00607.x

68. Zhang M, He Y, Sun X, Li Q, Wang W, Zhao A, et al. high M1/M2 ratio of tumor-associated macrophages is associated with extended survival in ovarian cancer patients. J Ovarian Res. (2014) 7:19. doi: 10.1186/1757-2215-7-19

69. Biswas SK, Mantovani A. Macrophage plasticity and interaction with lymphocyte subsets: cancer as a paradigm. Nat Immunol. (2010) 11:889–96. doi: 10.1038/ni.1937

70. DeNardo DG, Ruffell B. Macrophages as regulators of tumour immunity and immunotherapy. Nat Rev Immunol. (2019) 19:369–82. doi: 10.1038/s41577-019-0127-6

71. Murray PJ, Allen JE, Biswas SK, Fisher EA, Gilroy DW, Goerdt S, et al. Macrophage activation and polarization: nomenclature and experimental guidelines. Immunity. (2014) 41:14–20. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2014.06.008

72. Azizi E, Carr AJ, Plitas G, Cornish AE, Konopacki C, Prabhakaran S, et al. Single-Cell Map of diverse immune phenotypes in the breast tumor microenvironment. Cell. (2018) 174:1293–308. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2018.05.060

73. Gubin MM, Esaulova E, Ward JP, Malkova ON, Runci D, Wong P, et al. High-dimensional analysis delineates myeloid and lymphoid compartment remodeling during successful immune-checkpoint cancer therapy. Cell. (2018) 175:1014–30. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2018.09.030

74. Uribe-Querol E, Rosales C. Neutrophils in cancer: two sides of the same coin. J Immunol Res. (2015) 2015:983698. doi: 10.1155/2015/983698

75. Shaul ME, Fridlender ZG. Cancer-related circulating and tumor-associated neutrophils – subtypes, sources and function. FEBS J. (2018) 285:4316–42. doi: 10.1111/febs.14524

76. Fridlender ZG, Sun J, Kim S, Kapoor V, Cheng G, Ling L, et al. Polarization of tumor-associated neutrophil phenotype by TGF-β: “N1” vs. “N2” TAN. Cancer Cell. (2009) 16:183–94. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2009.06.017

77. Cortesi F, Delfanti G, Casorati G, Dellabona P. The pathophysiological relevance of the inkt cell/mononuclear phagocyte crosstalk in tissues. Front Immunol. (2018) 9:375. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2018.02375

78. Marvel D, Gabrilovich DI. Myeloid-derived suppressor cells in the tumor microenvironment: Expect the unexpected. J Clin Invest. (2015) 125:3356–64. doi: 10.1172/JCI80005

79. Roberts EW, Broz ML, Binnewies M, Headley MB, Nelson AE, Wolf DM, et al. Critical Role for CD103(+)/CD141(+) dendritic cells bearing ccr7 for tumor antigen trafficking and priming of t cell immunity in melanoma. Cancer Cell. (2016) 30:324–36. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2016.06.003

80. Turley SJ, Cremasco V, Astarita JL. Immunological hallmarks of stromal cells in the tumour microenvironment. Nat Rev Immunol. (2015) 15:669–82. doi: 10.1038/nri3902

81. Jahchan NS, Mujal AM, Pollack JL, Binnewies M, Sriram V, Reyno L, et al. Tuning the tumor myeloid microenvironment to fight cancer. Front Immunol. (2019) 10:611. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2019.01611

82. Bricard G, Cesson V, Devevre E, Bouzourene H, Barbey C, Rufer N, et al. Enrichment of Human CD4 + Vα24/Vβ11 Invariant NKT cells in intrahepatic malignant tumors. J Immunol. (2009) 182:5140–51. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0711086

83. De Santo C, Salio M, Masri SH, Lee LY-H, Dong T, Speak AO, et al. Invariant NKT cells reduce the immunosuppressive activity of influenza A virus-induced myeloid-derived suppressor cells in mice and humans. J Clin Invest. (2008) 118:4036–48. doi: 10.1172/JCI36264

84. De Santo C, Arscott R, Booth S, Karydis I, Jones M, Asher R, et al. Invariant NKT cells modulate the suppressive activity of IL-10-secreting neutrophils differentiated with serum amyloid A. Nat Immunol. (2010) 11:1039–46. doi: 10.1038/ni.1942

85. Song L, Asgharzadeh S, Salo J, Engell K, Wu HW, Sposto R, et al. Vα24-invariant NKT cells mediate antitumor activity via killing of tumor-associated macrophages. J Clin Invest. (2009) 119:1524–36. doi: 10.1172/JCI37869

86. Ko H-J, Lee J-M, Kim Y-J, Kim Y-S, Lee K-A, Kang C-Y. Immunosuppressive myeloid-derived suppressor cells can be converted into immunogenic apcs with the help of activated nkt cells: an alternative cell-based antitumor vaccine. J Immunol. (2009) 182:1818–28. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0802430

87. Lee JM, Seo JH, Kim YJ, Kim YS, Ko HJ, Kang CY. The restoration of myeloid-derived suppressor cells as functional antigen-presenting cells by NKT cell help and all-trans-retinoic acid treatment. Int J Cancer. (2012) 131:741–51. doi: 10.1002/ijc.26411

88. Janakiram NB, Mohammed A, Bryant T, Ritchie R, Stratton N, Jackson L, et al. Loss of natural killer T cells promotes pancreatic cancer in LSL-KrasG12D/+ mice. Immunology. (2017) 152:36–51. doi: 10.1111/imm.12746

89. Wang Y, Sedimbi S, Löfbom L, Singh AK, Porcelli SA, Cardell SL. Unique invariant natural killer T cells promote intestinal polyps by suppressing TH1 immunity and promoting regulatory T cells. Mucosal Immunol. (2018) 11:131–43. doi: 10.1038/mi.2017.34

90. Wang Y, Sedimbi SK, Löfbom L, Besra GS, Porcelli SA, Cardell SL. Promotion or suppression of murine intestinal polyp development by iNKT cell directed immunotherapy. Front Immunol. (2019) 10: doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2019.00352

91. Tsukada N, Burger JA, Zvaifler NJ, Kipps TJ. Distinctive features of “nurselike” cells that differentiate in the context of chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Blood. (2002) 99:1030–7. doi: 10.1182/blood.V99.3.1030

92. Parekh V V. Glycolipid antigen induces long-term natural killer T cell anergy in mice. J Clin Invest. (2005) 115:2572–83. doi: 10.1172/JCI24762

93. Parekh V V, Lalani S, Kim S, Halder R, Azuma M, Yagita H, et al. PD-1/PD-L blockade prevents anergy induction and enhances the anti-tumor activities of glycolipid-activated invariant NKT Cells. J Immunol. (2009) 182:2816–26. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0803648

94. Wang Y, Bhave MS, Yagita H, Cardell SL. Natural Killer T-Cell Agonist α-Galactosylceramide and PD-1 blockade synergize to reduce tumor development in a preclinical model of colon cancer. Front Immunol. (2020) 11:1–12. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2020.581301

95. Bedard M, Salio M, Cerundolo V. Harnessing the power of invariant natural killer T cells in cancer immunotherapy. Front Immunol. (2017) 8:829. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2017.01829

96. Krijgsman D, Hokland M, Kuppen PJK. The role of natural killer T cells in cancer-A phenotypical and functional approach. Front Immunol. (2018) 9:367. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2018.00367

97. Chan JD, Lai J, Slaney CY, Kallies A, Beavis PA, Darcy PK. Cellular networks controlling T cell persistence in adoptive cell therapy. Nat Rev Immunol. (2021) 21:769–84. doi: 10.1038/s41577-021-00539-6

98. Anderson KG, Stromnes IM, Greenberg PD. Obstacles Posed by the tumor microenvironment to t cell activity: a case for synergistic therapies. Cancer Cell. (2017) 31:311–25. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2017.02.008

99. Pillai AB, George TI, Dutt S, Teo P, Strober S. Host NKT cells can prevent graft-versus-host disease and permit graft antitumor activity after bone marrow transplantation. J Immunol. (2007) 178:6242–51. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.10.6242

100. Morris ES, MacDonald KPA, Rowe V, Banovic T, Kuns RD, Don ALJ, et al. NKT cell-dependent leukemia eradication following stem cell mobilization with potent G-CSF analogs. J Clin Invest. (2005) 115:3093–103. doi: 10.1172/JCI25249

101. Chaidos A, Patterson S, Szydlo R, Chaudhry MS, Dazzi F, Kanfer E, et al. Graft invariant natural killer T-cell dose predicts risk of acute graft-versus-host disease in allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Blood. (2012) 119:5030–6. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-11-389304

102. Rubio M-T, Moreira-Teixeira L, Bachy E, Bouillié M, Milpied P, Coman T, et al. Early posttransplantation donor-derived invariant natural killer T-cell recovery predicts the occurrence of acute graft-versus-host disease and overall survival. Blood. (2012) 120:2144–54. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-01-404673

103. Guan P, Bassiri H, Patel NP, Nichols KE, Das R. Invariant natural killer T cells in hematopoietic stem cell transplantation: killer choice for natural suppression. Bone Marrow Transplant. (2016) 51:629–37. doi: 10.1038/bmt.2015.335

104. Schneidawind D, Baker J, Pierini A, Buechele C, Luong RH, Meyer EH, et al. Third-party CD4+ invariant natural killer T cells protect from murine GVHD lethality. Blood. (2015) 125:3491–500. doi: 10.1182/blood-2014-11-612762

105. Shissler SC, Lee MS, Webb TJ. Mixed signals: co-stimulation in invariant natural killer T cell-mediated cancer immunotherapy. Front Immunol. (2017) 8: doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2017.01447

106. Li Y-R, Zhou Y, Kim YJ, Zhu Y, Ma F, Yu J, et al. Development of allogeneic HSC-engineered iNKT cells for off-the-shelf cancer immunotherapy. Cell Reports Med. (2021) 2:100449. doi: 10.1016/j.xcrm.2021.100449

107. Gornalusse GG, Hirata RK, Funk SE, Riolobos L, Lopes VS, Manske G, et al. HLA-E-expressing pluripotent stem cells escape allogeneic responses and lysis by NK cells. Nat Biotechnol. (2017) 35:765–72. doi: 10.1038/nbt.3860

108. Kim MJ, Lee J-C, Lee J-J, Kim S, Lee SG, Park S-W, et al. Association of CD47 with Natural Killer Cell-Mediated Cytotoxicity of Head-and-Neck Squamous Cell Carcinoma Lines. Tumor Biol. (2008) 29:28–34. doi: 10.1159/000132568

109. Exley MA, Wilson SB, Balk SP. Isolation and functional use of human NKT cells. Curr Protoc Immunol. (2017) 2017:14.11.1-14.11.20. doi: 10.1002/cpim.33

110. Watarai H, Fujii S, Yamada D, Rybouchkin A, Sakata S, Nagata Y, et al. Murine induced pluripotent stem cells can be derived from and differentiate into natural killer T cells. J Clin Invest. (2010) 120:2610–8. doi: 10.1172/JCI42027

111. Yamada D, Iyoda T, Vizcardo R, Shimizu K, Sato Y, Endo TA, et al. Efficient Regeneration of Human Vα24 + Invariant Natural Killer T Cells and Their Anti-Tumor Activity In Vivo. Stem Cells. (2016) 34:2852–60. doi: 10.1002/stem.2465

112. Zhu Y, Smith DJ, Zhou Y, Li YR, Yu J, Lee D, et al. Development of hematopoietic stem cell-engineered invariant natural killer t cell therapy for cancer. Cell Stem Cell. (2019) 25:542–557. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2019.08.004

113. Giaccone G, Punt CJA, Ando Y, Ruijter R, Nishi N, Peters M, et al. A phase I study of the natural killer T-cell ligand alpha-galactosylceramide (KRN7000) in patients with solid tumors. Clin Cancer Res. (2002) 8:3702–9.

114. Nieda M, Okai M, Tazbirkova A, Lin H, Yamaura A, Ide K, et al. Therapeutic activation of Vα24+Vβ11+ NKT cells in human subjects results in highly coordinated secondary activation of acquired and innate immunity. Blood. (2004) 103:383–9. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-04-1155

115. Nicol AJ, Tazbirkova A, Nieda M. Comparison of Clinical and Immunological Effects of Intravenous and Intradermal Administration of α-GalactosylCeramide (KRN7000)-Pulsed Dendritic Cells. Clin Cancer Res. (2011) 17:5140–51. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-3105

116. Chang DH, Osman K, Connolly J, Kukreja A, Krasovsky J, Pack M, et al. Sustained expansion of NKT cells and antigen-specific T cells after injection of α-galactosyl-ceramide loaded mature dendritic cells in cancer patients. J Exp Med. (2005) 201:1503–17. doi: 10.1084/jem.20042592

117. Ishikawa A, Motohashi S, Ishikawa E, Fuchida H, Higashino K, Otsuji M, et al. phase I study of alpha-galactosylceramide (KRN7000)-pulsed dendritic cells in patients with advanced and recurrent non-small cell lung cancer. Clin Cancer Res. (2005) 11:1910–7. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-1453

118. Motohashi S, Ishikawa A, Ishikawa E, Otsuji M, Iizasa T, Hanaoka H, et al. A phase I study of in vitro expanded natural killer T cells in patients with advanced and recurrent non-small cell lung cancer. Clin Cancer Res. (2006) 12:6079–86. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-0114

119. Uchida T, Horiguchi S, Tanaka Y, Yamamoto H, Kunii N, Motohashi S, et al. Phase I study of α-galactosylceramide-pulsed antigen presenting cells administration to the nasal submucosa in unresectable or recurrent head and neck cancer. Cancer Immunol Immunother. (2008) 57:337–45. doi: 10.1007/s00262-007-0373-5

120. Motohashi S, Nagato K, Kunii N, Yamamoto H, Yamasaki K, Okita K, et al. A Phase I-II Study of α-Galactosylceramide-Pulsed IL-2/GM-CSF-cultured peripheral blood mononuclear cells in patients with advanced and recurrent non-small cell lung cancer. J Immunol. (2009) 182:2492–501. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0800126

121. Kunii N, Horiguchi S, Motohashi S, Yamamoto H, Ueno N, Yamamoto S, et al. Combination therapy of in vitro-expanded natural killer T cells and α-galactosylceramide-pulsed antigen-presenting cells in patients with recurrent head and neck carcinoma. Cancer Sci. (2009) 100:1092–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2009.01135.x

122. Yamasaki K, Horiguchi S, Kurosaki M, Kunii N, Nagato K, Hanaoka H, et al. Induction of NKT cell-specific immune responses in cancer tissues after NKT cell-targeted adoptive immunotherapy. Clin Immunol. (2011) 138:255–65. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2010.11.014

123. Kurosaki M, Horiguchi S, Yamasaki K, Uchida Y, Motohashi S, Nakayama T, et al. Migration and immunological reaction after the administration of αgalCer-pulsed antigen-presenting cells into the submucosa of patients with head and neck cancer. Cancer Immunol Immunother. (2011) 60:207–15. doi: 10.1007/s00262-010-0932-z

124. Nagato K, Motohashi S, Ishibashi F, Okita K, Yamasaki K, Moriya Y, et al. Accumulation of activated invariant natural killer T cells in the tumor microenvironment after α-galactosylceramide-pulsed antigen presenting cells. J Clin Immunol. (2012) 32:1071–81. doi: 10.1007/s10875-012-9697-9

125. Exley MA, Friedlander P, Alatrakchi N, Vriend L, Yue S, Sasada T, et al. Adoptive transfer of invariant NKT cells as immunotherapy for advanced melanoma: a phase I clinical trial. Clin Cancer Res. (2017) 23:3510–9. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-16-0600

126. Gasser O, Sharples KJ, Barrow C, Williams GM, Bauer E, Wood CE, et al. A phase I vaccination study with dendritic cells loaded with NY-ESO-1 and α-galactosylceramide: induction of polyfunctional T cells in high-risk melanoma patients. Cancer Immunol Immunother. (2018) 67:285–98. doi: 10.1007/s00262-017-2085-9

127. Heczey A, Courtney AN, Montalbano A, Robinson S, Liu K, Li M, et al. Anti-GD2 CAR-NKT cells in patients with relapsed or refractory neuroblastoma: an interim analysis. Nat Med. (2020) 26:1686–90. doi: 10.1038/s41591-020-1074-2

128. Wolf BJ, Choi JE, Exley MA. Novel approaches to exploiting invariant NKT cells in cancer immunotherapy. Front Immunol. (2018) 9:384. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2018.00384

129. Heczey A, Liu D, Tian G, Courtney AN, Wei J, Marinova E, et al. Invariant NKT cells with chimeric antigen receptor provide a novel platform for safe and effective cancer immunotherapy. Blood. (2014) 124:2824–33. doi: 10.1182/blood-2013-11-541235

130. Tian G, Courtney AN, Jena B, Heczey A, Liu D, Marinova E, et al. CD62L+ NKT cells have prolonged persistence and antitumor activity in vivo. J Clin Invest. (2016) 126:2341–55. doi: 10.1172/JCI83476

131. Rotolo A, Caputo VS, Holubova M, Baxan N, Dubois O, Chaudhry MS, et al. Enhanced anti-lymphoma activity of CAR19-iNKT cells underpinned by dual CD19 and CD1d targeting. Cancer Cell. (2018) 341:596-610. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2018.08.017

132. Poels R, Drent E, Lameris R, Katsarou A, Themeli M, van der Vliet HJ, et al. Preclinical evaluation of invariant natural killer t cells modified with cd38 or bcma chimeric antigen receptors for multiple myeloma. Int J Mol Sci. (2021) 22:1096. doi: 10.3390/ijms22031096

133. Xu X, Huang W, Heczey A, Liu D, Guo L, et al. NKT cells co-expressing a GD2-specific chimeric antigen receptor and IL-15 show enhanced in vivo persistence and antitumor activity against neuroblastoma. Clin Cancer Res. (2019) 421:2019. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.ccr-19-0421

134. Simonetta F, Lohmeyer JK, Hirai T, Maas-Bauer K, Alvarez M, Wenokur AS, et al. Allogeneic CAR invariant natural killer T cells exert potent antitumor effects through host CD8 T-cell cross-priming. Clin Cancer Res. (2021) 27:6054–64. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-21-1329

135. Jiang Z-M, Luo W, Wen Q, Liu S-D, Hao P-P, Zhou C-Y, et al. Development of genetically engineered iNKT cells expressing TCRs specific for the M. tuberculosis 38-kDa antigen J Transl Med. (2015) 13:141. doi: 10.1186/s12967-015-0502-4

136. Landoni E, Smith CC, Fucá G, Chen Y, Sun C, Vincent BG, Metelitsa LS, Dotti G, Savoldo B. A high avidity t-cell receptor redirects natural killer t-cell specificity and outcompetes the endogenous invariant t-cell receptor. Cancer Immunol Res. (2019) 19:134. doi: 10.1158/2326-6066.CIR-19-0134

137. Ellis GI, Sheppard NC, Riley JL. Genetic engineering of T cells for immunotherapy. Nat Rev Genet. (2021) 22:427–47. doi: 10.1038/s41576-021-00329-9

Keywords: NKT cells, CD1d, cancer immunotherapy, CAR, T cell receptor, adoptive cell therapy (ACT)

Citation: Delfanti G, Dellabona P, Casorati G and Fedeli M (2022) Adoptive Immunotherapy With Engineered iNKT Cells to Target Cancer Cells and the Suppressive Microenvironment. Front. Med. 9:897750. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2022.897750

Received: 16 March 2022; Accepted: 14 April 2022;

Published: 09 May 2022.

Edited by:

Sebastien Jaillon, Humanitas University, ItalyReviewed by:

Federica Facciotti, European Institute of Oncology (IEO), ItalyMariolina Salio, University of Oxford, United Kingdom

Copyright © 2022 Delfanti, Dellabona, Casorati and Fedeli. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Gloria Delfanti, delfanti.gloria@hsr.it; Giulia Casorati, casorati.giulia@hsr.it; Maya Fedeli, fedeli.maya@hsr.it

Gloria Delfanti

Gloria Delfanti Paolo Dellabona

Paolo Dellabona Giulia Casorati

Giulia Casorati Maya Fedeli

Maya Fedeli