The Experiences of Functioning and Health of Patients With Primary Sjögren's Syndrome: A Multicenter Qualitative European Study

- 1Department of Rheumatology and Immunology, Medical University of Graz, Graz, Austria

- 2Department of Health Studies, Institute of Occupational Therapy, University of Applied Sciences FH JOANNEUM, Bad Gleichenberg, Austria

- 3Division of Physiotherapy, Department of Neurobiology, Care Sciences and Society, Karolinska Institutet, and Affiliated to Women's Health and Allied Health Professionals Theme, Medical Unit Occupational Therapy and Physical Therapy, Karolinska University Hospital, Stockholm, Sweden

- 4Department of Physiotherapy, Sunderby Hospital, Luleå, Sweden

- 5Department of Balneology, Rehabilitation Medicine and Rheumatology, “Victor Babeş” University of Medicine and Pharmacy Timisoara, Timisoara, Romania

- 6Department of Physical Therapy and Special Motility, West University of Timisoara, Timisoara, Romania

- 7Department of Rheumatology and Clinical Immunology, Charitè University Medicine, Berlin, Germany

- 8Department of Rheumatology and Immunology, Medical University of Hanover, Hanover, Germany

- 9Department of Rheumatology, Hospital of Bolzano (SABES-ASDAA), Bolzano, Italy

- 10Evangelic Hospital of Vienna, Vienna, Austria

- 11Division of Rheumatology and Immunology, Department of Internal Medicine, Medical University Vienna, Vienna, Austria

- 12Section for Outcomes Research, Centre for Medical Statistics, Informatics, and Intelligent Systems, Medical University Vienna, Vienna, Austria

- 13Department of Rheumatology, Hospital of Brunico (SABES-ASDAA), Brunico, Italy

Objective: To identify a spectrum of perspectives on functioning and health of patients with primary Sjögren's syndrome (pSS) from the five European countries in order to reveal commonalities and insights in their experiences.

Methods: A multicenter focus group study on the patients with pSS about their perspectives of functioning and health was performed. Focus groups were chaired by trained moderators based on an interview guide, audiotaped, and transcribed. After conducting a meaning condensation analysis of each focus group, we subsequently combined the extracted concepts from each country and mapped them to the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF).

Results: Fifty-one patients with pSS participated in 12 focus groups. We identified a total of 82 concepts meaningful to people with pSS. Of these, 55 (67%) were mentioned by the patients with pSS in at least four of five countries and 36 (44%) emerged in all the five countries. Most concepts were assigned to the ICF components activities and participation (n = 25, 30%), followed by 22 concepts (27%) that were considered to be not definable or not covered by the ICF; 15 concepts (18%) linked to body structures and functions. Participants reported several limitations in the daily life due to a mismatch between the capabilities of the person, the demands of the environment and the requirements of the activities.

Conclusion: Concepts that emerged in all the five non-English speaking countries may be used to guide the development and adaption of the patient-reported outcome measures and to enhance the provision of treatment options based on the aspects meaningful to patients with pSS in clinical routine.

Introduction

Primary Sjögren's syndrome (pSS) is an autoimmune disease of unknown etiology with female predominance that is characterized by an inflammation of exocrine glands, particularly salivary and lachrymal glands as well as variable extra-glandular manifestations such as musculoskeletal, gastrointestinal, and/or neurological symptoms (1–3). Patients with pSS can experience multiple facets of the mucosal dryness, pain, fatigue, and other complaints resulting in an impairment in everyday life and an altered health-related quality of life (HRQoL) (4–9).

Perceptions of the disease may not only differ between the patients and health professionals (10, 11), but also between individuals suffering from the same condition (12). This is majorly due to that the perception is built upon several mental sources that are implicit and specific to the individuals (13). A recent study in the psoriatic arthritis (PsA) highlighted the influence of cultural backgrounds on differences in the perception of illness (14). The illness perception is dependent on the disease activity, and negative views of the illness are linked to the worse future health outcomes (15–17) whereas positive beliefs are associated with the better health outcomes (18–21).

Patient-reported outcomes (PROs) represent the “voice of the patient” and are increasingly applied in the research studies and clinical practice to ensure a patient-centered care (22, 23). PRO Measurements (PROMs) are the instruments to measure PROs. Several PROMs are available for pSS, however, only a few of them have been validated (24). Besides, the patients from non-English countries rarely participate in the studies aimed at the development or validation of PROMs leading to the underrepresentation of the specific cultural context of these countries in the final PROM (25). PROMs are therefore often cross-culturally adapted only later after their development (25, 26). However, the cross-cultural adaption of PROMs is linked with challenges such as not being familiar with different cultures or not considering geographical variations and differences in the physical and social infrastructure. Thus, cultural equivalence is not always achieved (25, 27–29).

An approach to truly capture what is important to the patients is qualitative methodology. It offers the opportunity to explore the perspectives, motivations, values, beliefs, and needs of the patients in a scientific and systematic manner. A qualitative approach supports the development of a deeper understanding of the patient perspective and enables the examination of complex issues that cannot be measured using strictly defined variables (30). The aggregation of views of the patients in a non-numeric, descriptive way can facilitate more patient-centered decisions (31) ultimately improving the quality of care.

Due to the increased relevance of the patient perspective (3), there is a growing body of qualitative evidence on the experiences of patients with pSS (7, 32–36). Thereby, the general impact of pSS on (health related) quality of life (33) or daily life (32, 36) was studied and specific aspects of the disease like physical, mental or ocular fatigue (34), fatigue, sleep, and pain (35), sleep disruption (7) or treatment experiences (32) were evaluated. However, all of these previous studies were conducted on a national level. None of them examined the perspectives of patients with pSS from different countries in one study so far, focusing on a consistent data collection and data analysis and taking potential cultural, geographical, and social variations into account.

In this study, the main objective was to identify a spectrum of perspectives on the functioning and health of patients with pSS in the five European countries in order to reveal commonalities and insights in their experiences.

Patients and Methods

Study Design

We conducted a qualitative multicenter study using the focus groups (37) in seven rheumatology centers in five European countries, namely, Austria, Germany, Italy, Romania, and Sweden. The “COnsolidated criteria for REporting QUalitative research” (COREQ)—guideline provided by the EQUATOR Network was used for the reporting of this study (38).

Patients and Sampling

Patients with pSS had to meet the American–European Consensus Group Classification criteria, (6) and were recruited via telephone or face-to-face by the local investigators (BR, FB, TW, MD, MM, RD, CA, and PP) of the participating centers. Patients who already participated in another study at the same time or who had severe mental problems were excluded. Patients had to be fluent in the local language. We aimed to follow purposeful sampling by selecting patients of different ages and gender. However, pSS is predominantly affecting women (1–3, 39). According to the other qualitative studies in rheumatology (30, 40) and to balance the data quality and data quantity, we recruited two to four focus groups per country in order to gain data of enough richness.

Data Collection

All focus groups were chaired by the trained moderators at the local rheumatology centers: JU (female, PhD student, occupational therapist) for Austria, Germany, and Italy, RD and CA (males, PhD, medical doctors) for Romania and MM (female, Ph.D., physiotherapist) for Sweden. We developed a common interview guide, which was translated into local languages, back translated, pilot tested, and refined. Interview questions used in this study are depicted in the supplement files (Supplementary Table S1). If necessary, field notes were taken during the focus groups by the moderators. Each focus group was audiotaped and transcribed in the local language. Ethical approval was obtained in each center, and all the participants provided oral and written informed consent.

Data Analysis

The data analysis was carried out independently by the local researchers (JU for Austria, Germany, and Italy; RD for Romania; MM and CB for Sweden), using the method of meaning condensation (41). This involved the following four steps: first, local researchers read through all the focus groups transcripts and potential field notes of his/her center in order to become familiar with the data material. Second, specific units of a text, a few words, or a few sentences with a common meaning were identified in the data and defined as “meaning units”. Third, subconcepts contained in the “meaning units” were identified. A “meaning unit” could obtain more than one subconcept. Fourth, these subconcepts were grouped together to more comprehensive “higher-level” concepts, which were formulated by the local researchers in English language. A professional qualitative data analysis and research software known as Atlas.ti was used for the management of the data material (42).

After the focus groups were analyzed in each country, a one-day meeting with all researchers who conducted and analyzed the focus groups (JU, MM, and RD) was held. An experienced researcher (TAS) moderated this meeting, at which concepts from the five countries were compared and grouped together according to their meaning. Thereby, concepts representing the perspectives of the patients with pSS on functioning and health were identified. In order to describe these concepts in a standardized way with a common language, we used the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF) (43). This integrative biopsychosocial model, created by the WHO, is a highly recognized framework for classification that enables the description of problems of the patient, the selection of important outcome domains or the comparison of health information (43, 44). Hereinafter, two investigators (JU and AL) independently linked the concepts identified in the focus groups to the most precise ICF category according to the published linking rules (45). In case of any disagreement, the consensus was sought by discussion among the investigators.

Rigor and Accuracy of the Qualitative Data Collection and Analysis

In order to ensure rigor and accuracy of the study, we followed several approaches. A detailed draft of the study protocol was available for all the study members prior to the beginning of the study. We ensured that the local researchers had the required knowledge and conducted an extensive training and debriefing session before data collection. Furthermore, we established a detailed track record for the data collection process that determined important conditions for conducting the focus groups. After data retrieval, a pilot analysis was done by each local researcher (CB, MM, JU, and RD) before the full proper analysis was conducted. The whole process was supervised by a researcher with extensive experience in the field of qualitative research (TAS). Both investigators (JU and AL) who conducted the ICF-linking process were trained in linking concepts to the ICF.

Results

Participants and Focus Groups

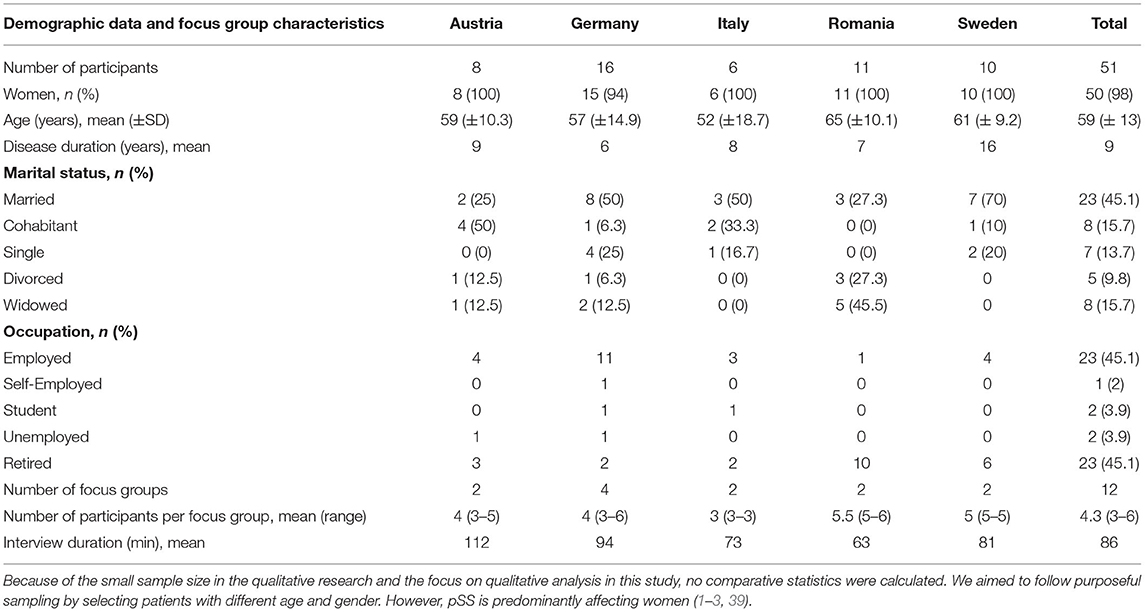

Demographic information from 51 patients with pSS who participated in 12 focus groups is provided in Table 1.

Concepts Identified in the Focus Groups and Their ICF Linkage

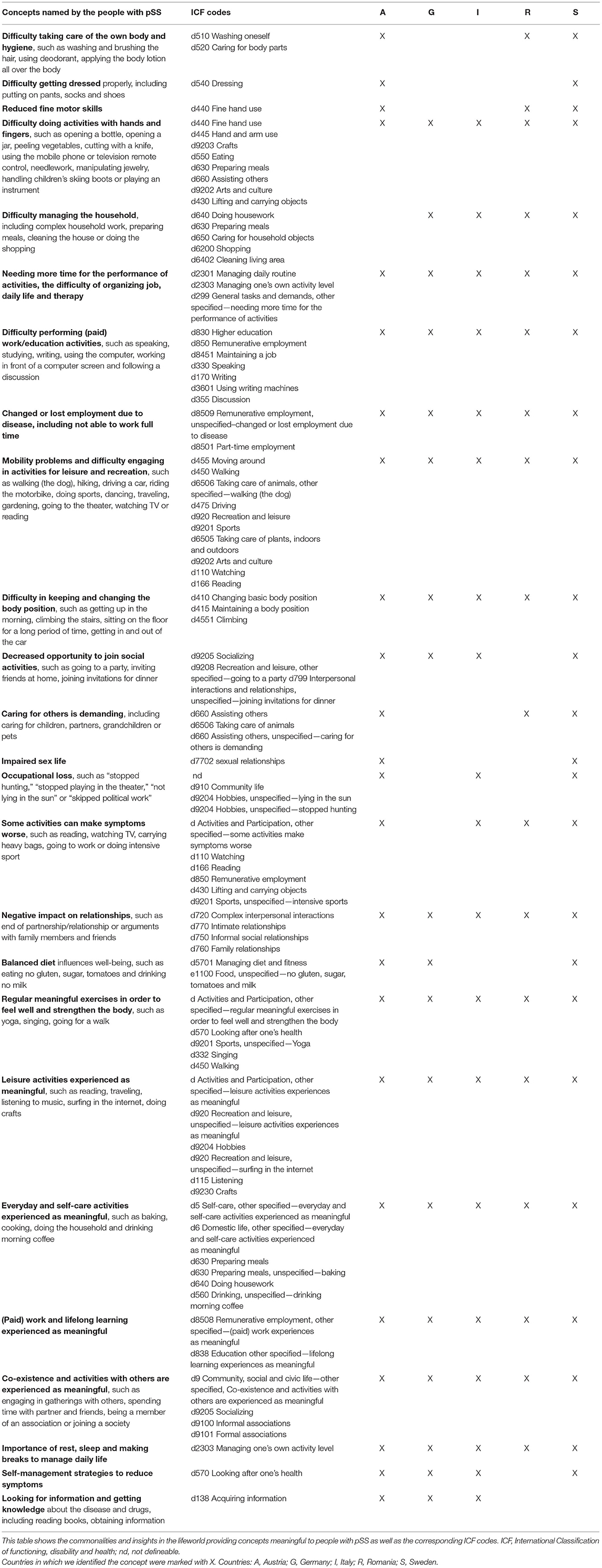

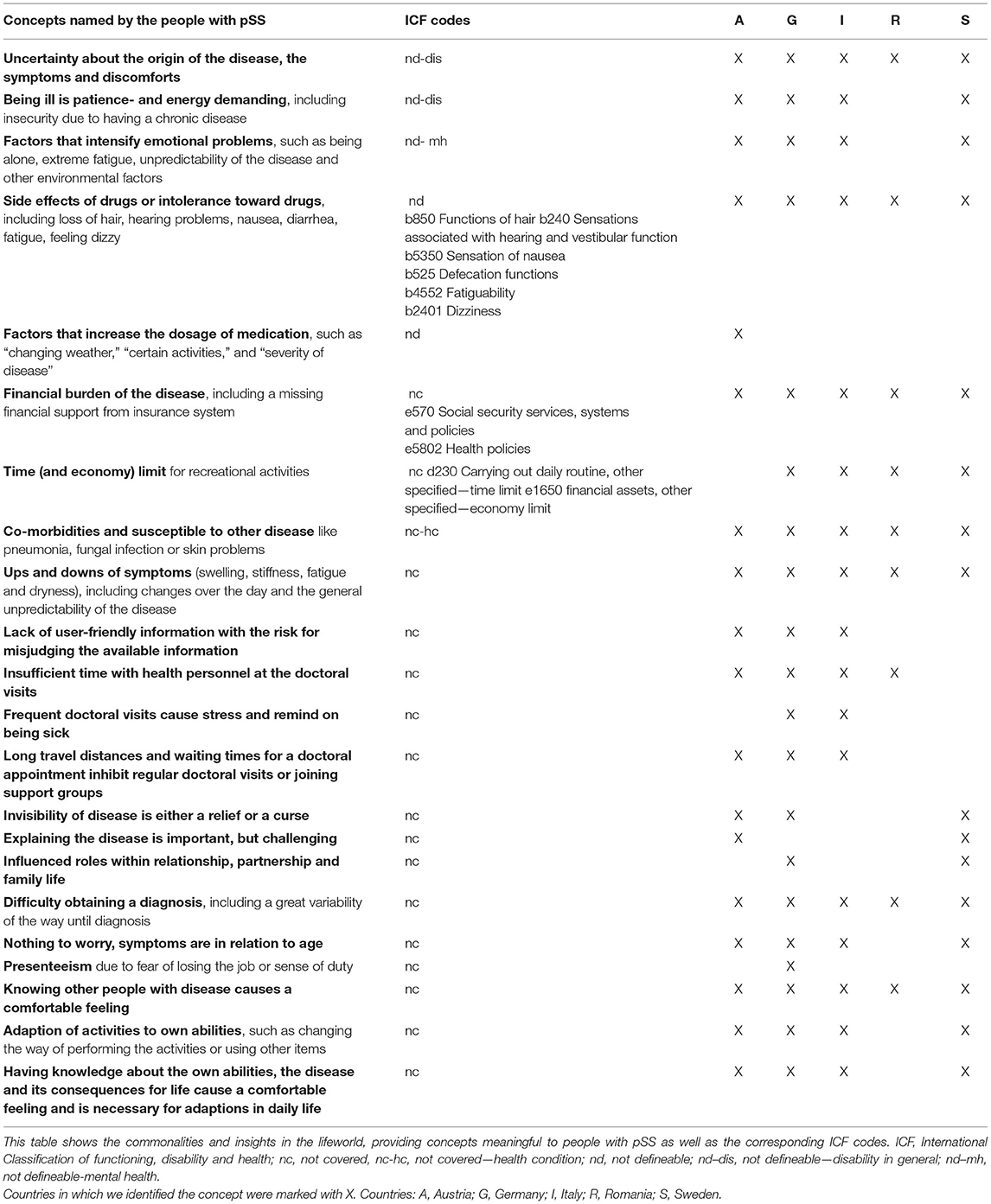

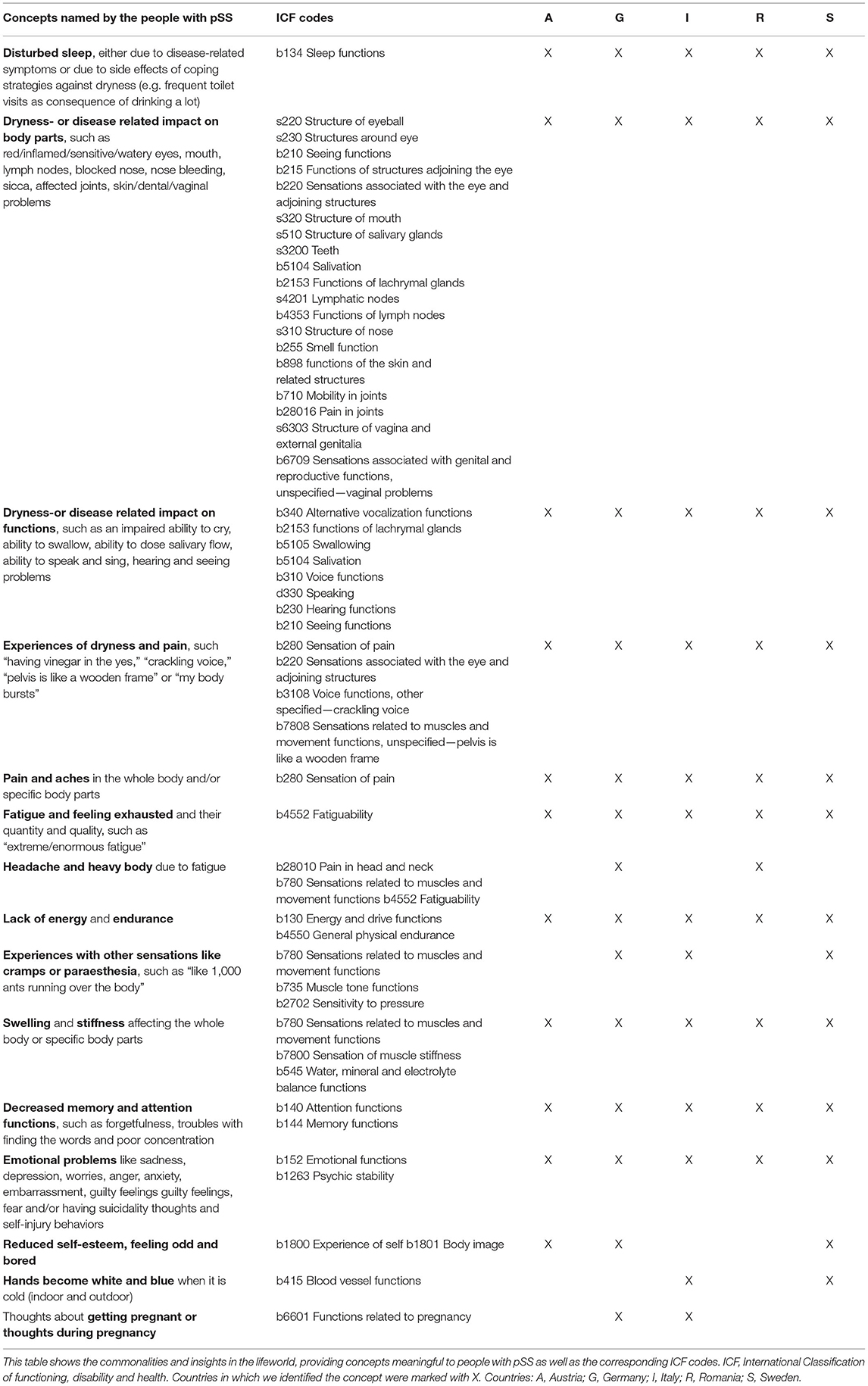

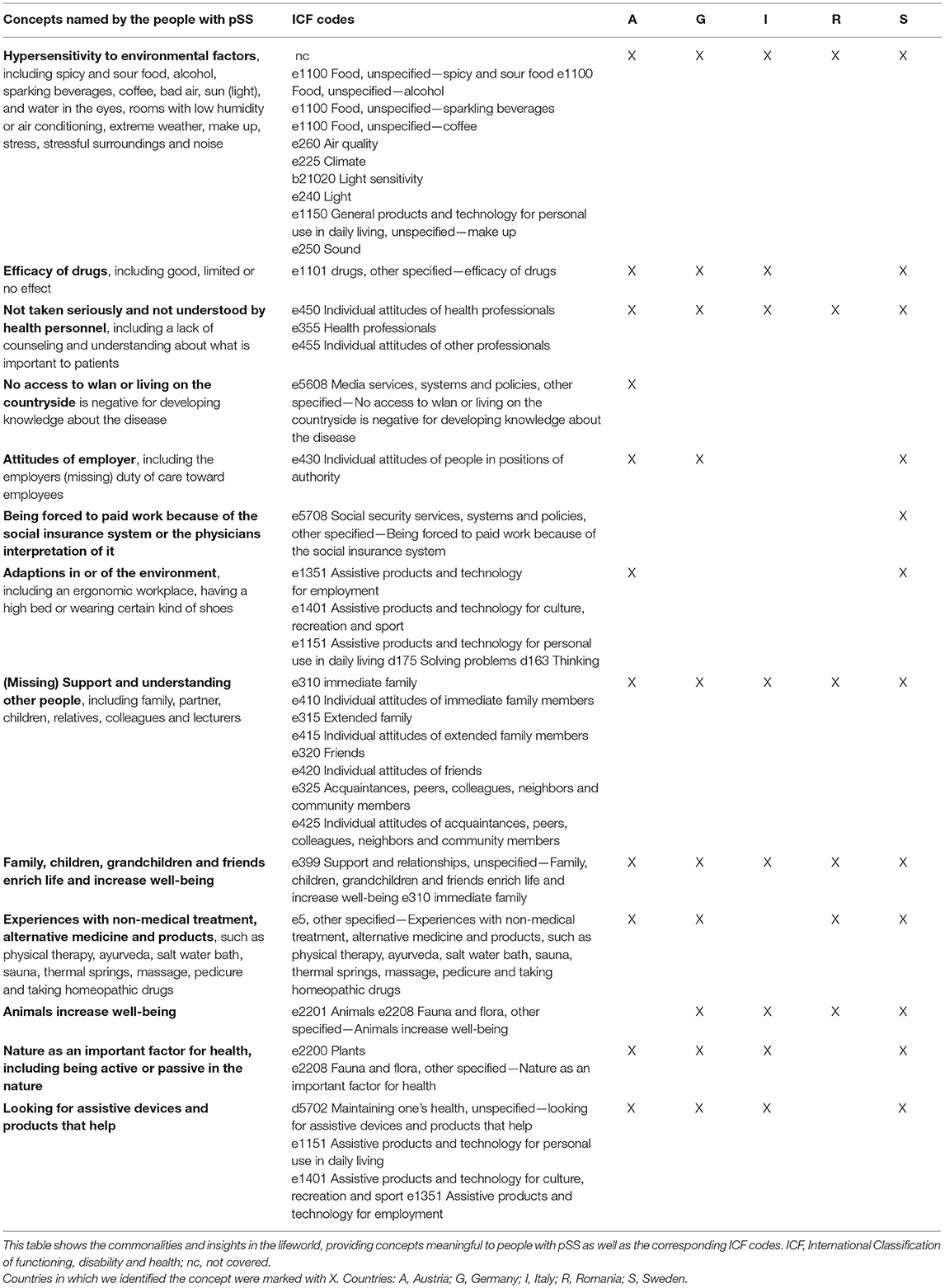

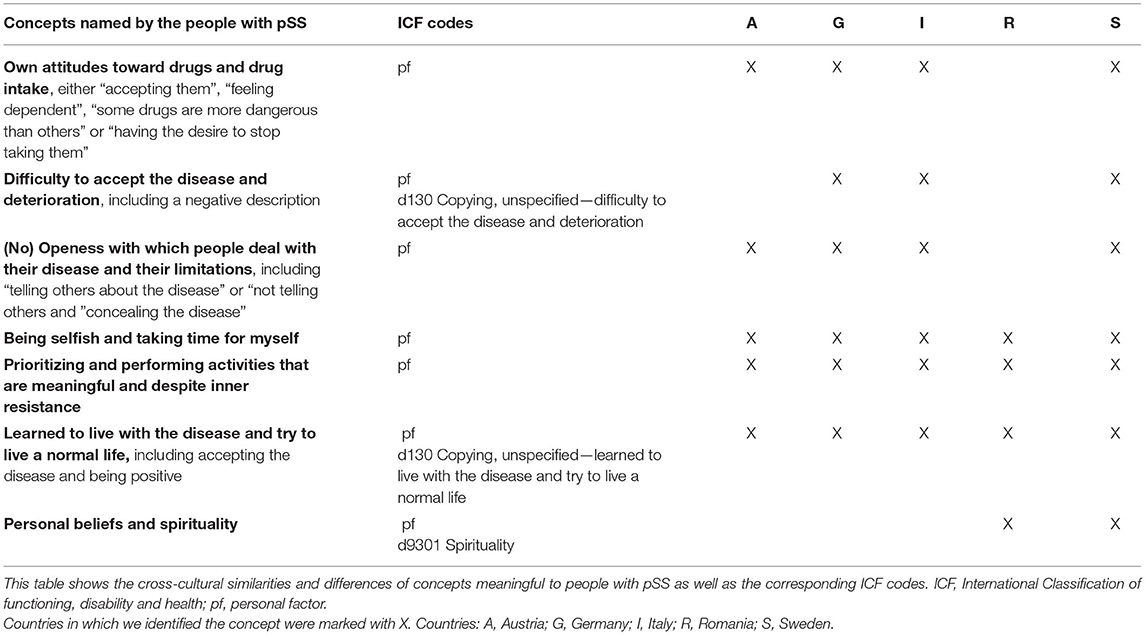

The local investigators (JU, MM/CB, and RD) identified 184 subconcepts in Austria, 156 in Germany, 151 in Italy, 98 in Romania, and 103 in Sweden. After the one-day-meeting of the local investigators, the analysis of all focus groups resulted in 82 concepts meaningful to the patients with pSS. Out of these 82 concepts, the largest number of concepts (n = 25, 30%) was linked to the ICF component activities and participation. The second largest number of concepts (n = 22, 27%) was considered to be not definable or not covered by the ICF. These concepts contained general facets of pSS such as the difficulty obtaining a diagnosis, the uncertainty of the origin of the disease or that being ill is patience and energy demanding. Fifteen (18%) concepts were linked to the ICF component body functions and structures, another 13 (16%) concepts expressed environmental factors. The remaining seven (9%) concepts revealed insights in the personal thoughts, coping styles and behavior patterns of patients with pSS and were therefore considered as personal factors. The ICF components of the concepts are shown in Tables 2–6 (column 2).

Commonalities and Insights in the Lifeworld of People With pSS

Out of 82 concepts, 55 (67%) were mentioned by the patients with pSS in at least four of five countries and 36 concepts (44%) emerged in all the five countries. Tables 2–6 gives an overview of the 82 concepts meaningful to the patients with pSS with their specific ICF codes.

Participants from all the countries reported several limitations in daily life, including self-care, productivity, and leisure. The reasons for these limitations are characterized by a mismatch between the capabilities of the person, the demands of the physical, social, and cultural environment, and the requirements to conduct the activity. A participant in Austria explained the impact of her decreased fine motor skills on the performance of activities as follows: “…in the morning, opening milk bottles or juice, that was impossible (…), but for example I cannot do anything with buttons, I cannot make the buttons, jewelry. I cannot do the little things. (…) you have to look what you wear, I want to put on a nice blouse, but I cannot do this if he (husband) is not at home because of the buttons.” Another example is given by a participant in Italy who described her experience with her decreased ability to remember things: “I am no longer receptive, I was a great student in high school, but when I started at the university (…), I was not able to remember things. I do not know what was happening, you know, from 1 day to the other, I just did not have the ability to concentrate anymore. When I attended lectures for 4 h in the morning, I did not know what was going on.”

How the environment can lead to participation restrictions was mentioned in all countries. One participant in Sweden clearly described: “Everybody else can go to town to go shopping, I cannot go inside (in the store) because of those big fans at the entrance, it does not work, my eyes do not manage it (the flowing air) at the entrance. So I am left outside waiting in the car.”

The importance of social support and understanding from other people was highlighted by the participants from all the five countries. In addition, the participants mentioned comfortable feeling that is created by knowing other people with the same disease. A participant in Austria explained it in the following way: “I think you meet so many friends and gossip with them about something. And you can't deal with your own problems with others, because they have no idea. So you can meet people who are concerned, and if you just have a coffee and chat…”.

However, it was not always possible to join support groups due to long travel distances. Some patients with pSS described the negative impact of long travel distances that inhibit them from visiting a healthcare provider or joining the support groups. Similar, but different is the concept about the negative impact of having no access to the internet or living on the countryside for the development of knowledge about disease.

Patients with pSS explained that they not always felt taken seriously and understood by the health personnel. One participant in Austria described it as follows: “…when you go to the dentist, he doesn't care (…), your whole mouth hurts anyway, because you don't have any saliva, and then he gives you the cotton wool, which is not ideal if you don't have any saliva. If he takes it out, he'll rip half of your skin with it. And then you say to him already five times ‘Listen'. And if he is not aware of Sjögren and I say, 'Listen, I have a dry mouth, please, watch out!', but he doesn't care.” At the same time the participants from four countries mentioned that the time with health personnel at routine visits is not sufficient. Furthermore, they specified the absence of user-friendly information and pointed the risk of misjudging. However, the importance of having knowledge about the own abilities, the disease and its consequences for life was found to be meaningful by the patients with pSS of the four countries.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first qualitative study on the European level that examined the perspectives of patients with pSS. We gained insights into the experiences of the patients with pSS from the Northern (Sweden), Central (Austria and Germany), and Southern/Eastern Europe (Italy, Romania). The results of our study highlight the importance of multinational data collection and go beyond previous small samples sized national studies, showing that the patients with pSS from different countries seem to experience similar challenges regarding their functioning and health. Concepts that expressed body functions and structures as well as concepts that were linked to activities and participation may be universal across the different European countries and might be used to guide the development and the cross-cultural adaption of the PROMs in pSS.

Our study led to the identification of 82 concepts; however, the largest number of concepts (n = 25, 30%) expressed aspects of an everyday living. This is in contrast to a study that aimed at exploring the perspectives of the patients with pSS on a national level (33), in which the concepts most often reported expressed the physical dimension of the disease. These differences may be explained by the multidimensional impact of pSS and the dynamic interaction between pSS, the affected body structures and functions and also the limitations in activities and restrictions in participation in relation to the personal and environmental factors.

Among the concepts found, the majority (67%) were mentioned by the people with pSS in at least four of five countries, and nearly half of the concepts (44%) were common in all the five countries. A similar observation was made in a recent study in which people with PsA from two different countries had two thirds of categories in common (14). In our study, two thirds of concepts assigned to body functions and structures (67%) and nearly half of the concepts related to the activities and participation (52%) were mentioned in all the five countries, indicating the importance of those two domains.

Some findings of our study are in line compared with other qualitative studies in pSS. We already know that the patients with pSS are confronted with a long way until diagnosis and thoughts about the origin of the disease and also the consequences of the disease on the physical, emotional, and social level (7, 33, 35, 36, 46, 47). We also know from other studies in pSS (33) and other rheumatic conditions that the patients sometimes feel that they are not taken seriously or that their complaints are dismissed by the health professionals (33, 46). The participants of our study specifically felt that the time the health personnel spent with them was insufficient. This is a notable result and should be seen in the context of ongoing debates about the future workforce requirements in rheumatology (48, 49). Current length of visits per patient and the time spent on the clinical care seem to be too short from point of view of the patients. Given that we expect an increasing lag between workforce supply and demand in the rheumatology in future, new concepts of care of pSS and other rheumatic patients might be needed.

Furthermore, attitudes toward drugs varied substantially between the participants of this study, either accepting them or feeling independent and having the desire to stop taking them. We do know from other studies that the attitudes toward taking drugs influence the adherence of the patients (50). Therefore, the health professionals should pay more attention to this point in order to ensure patient-centered care for the patients with pSS, also addressing non-pharmacological aspects and self-management strategies.

Our study has several limitations. First, we included a few European countries only. Considering the influence of social, cultural, and physical contexts into account, results might have been somewhat different if people from the other continents had participated in the study. On the other hand, we observed only few variations between the five countries (belonging to the Northern, Central, and Southern/Eastern Europe) studied, supporting the generalizability of our data.

Second, some concepts could have been influenced by the age, comorbidities, and other factors. Stratification of the focus groups according to these variables could have helped to measure the influence of these factors on the importance of the individual concepts. On the other hand, such an approach bore the risk that concepts emerged that are relevant for a small subgroup of the patients only. Our goal was to collect data representing the opinion and concerns of patients with pSS of everyday clinical practice and decided therefore against selecting patients according to the prespecified characteristics.

Third, the individual sample size in each country except Germany could have been bigger, however, saturation within the countries was reached that strengthens our results. We want to emphasize that the transferability of the identified lived experiences and perspectives is still limited, but a first attempt to investigate pSS with a cross-cultural understanding in order to inform practice and policy.

A specific strength of our study is that the health professionals with different occupations (occupational therapists, physicians, and physiotherapists) were involved in setting up the interview questions, analyzing and interpreting the data.

In conclusion, concepts meaningful to the patients with pSS identified in the five European countries might be used to guide the development and the adaption of PROMs. Concepts identified in this study enhance the clinical routine of the health professionals in order to provide support and treatment options based on the aspects relevant to the patients with pSS. However, the results of our study have to be considered preliminary and need to be confirmed by the future research.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets presented in this article are not available because participants of this study did not provide consent for the sharing of the transcripts of the focus groups. For further information please contact Julia Unger, julia.unger@fh-joanneum.at.

Ethics Statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by the Ethic Committees of each center: [EK 1653/2015, (Vienna, 8 September 2015), EudraCT/EOMpss/Sjögren Syndrom (Vienna, 24 February 2016), EA1/014/16 (Berlin, 28 April 2016), 2961-2015 (Hanover, 1 December 2015), 93-2015 (Italy, 16 September 2015), 27/16.12.2015 (Romania, 16 December 2015), and 2016/35-31Ö (Sweden, 15 March 2016)]. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author Contributions

TS, CD, and JU were involved in the study conception. BR, CB, FB, JU, MD, MM, PP, RD, TS, and TW were involved in the recruitment of the patients. CA, JU, MM, and RD collected the data. AL, CA, CB, CD, JU, MM, RD, and TS contributed substantially to analysis and interpretation of the data. CB, CD, JU, MM, RD, and TS drafted the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by a grant of the Austrian Association of Rheumatology and the Region Norrbotten. None of them were involved in the data collection, nor in the analysis or preparation of the manuscript.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Acknowledgments

The authors are indebted to the patients with pSS who kindly participated in this study and shared their perspectives, beliefs, and needs. We thank the Austrian Association of Rheumatology and the Region Norrbotten for partly funding this study. Parts of this work were presented at the conferences of EULAR and the Austrian Association of Rheumatology (51, 52).

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fmed.2021.770422/full#supplementary-material

References

1. Imgenberg-Kreuz J, Sandling JK, Nordmark G. Epigenetic alterations in primary Sjögren's syndrome—an overview. Clin Immunol. (2018) 196:12–20. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2018.04.004

3. Argyropoulou OD, Valentini E, Ferro F, Leone MC, Cafaro G, Bartoloni E, et al. One year in review 2018: Sjögren's syndrome. Clin Exp Rheumatol. (2018) 36:S14–26.

4. Liu Z, Dong Z, Liang X, Liu J, Xuan L, Wang J, et al. Health-related quality of life and psychological status of women with primary Sjögren's syndrome. Medicine. (2017) 96:e9208. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000009208

5. Al-Ezzi MY, Pathak N, Tappuni AR, Khan KS. Primary Sjögren's syndrome impact on smell, taste, sexuality and quality of life in female patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Mod Rheumatol. (2017) 27:623–9. doi: 10.1080/14397595.2016.1249538

6. Vitali C, Bombardieri S, Jonsson R, Moutsopoulos HM, Alexander EL, Carsons SE, et al. Classification criteria for Sjögren's syndrome: a revised version of the Erupean criteria proposed by the American- European Consensus Group. Ann Rheum Dis. (2002) 61:554–8. doi: 10.1136/ard.61.6.554

7. Hackett KL, Deary V, Deane KHO, Newton JL, Ng WF, Rapley T. Experience of sleep disruption in primary Sjögren's syndrome: a focus group study. Br J Occup Ther. (2018) 81:218–26. doi: 10.1177/0308022617745006

8. Koçer B, Tezcan ME, Batur HZ, Haznedaroglu S, Göker B, Irkeç C, et al. Cognition, depression, fatigue, and quality of life in primary Sjögren's syndrome: correlations. Brain Behav. (2016) 6:e00586. doi: 10.1002/brb3.586

9. Segal BM, Pogatchnik B, Henn L, Rudser K, Sivils KM. Pain severity and neuropathic pain symptoms in primary Sjögren's syndrome: a comparison study of seropositive and seronegative Sjögren's syndrome patients. Arthritis Care Res. (2013) 65:1291–8. doi: 10.1002/acr.21956

10. Arat S, Vandenberghe J, Moons P, Westhovens R. Patients' perceptions of their rheumatic condition: why moes it Matter and how can healthcare professionals influence or deal with these perceptions? Musculoskelet Care. (2016) 14:174–9. doi: 10.1002/msc.1128

11. Wen H, Ralph Schumacher H, Li X, Gu J, Ma L, Wei H, et al. Comparison of expectations of physicians and patients with rheumatoid arthritis for rheumatology clinic visits: a pilot, multicenter, international study. Int J Rheum Dis. (2012) 15:380–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1756-185X.2012.01752.x

12. Petrie K, Weinmann J. Why illness perceptions matter. Cinical Med. (2016) 6:536–9. doi: 10.7861/clinmedicine.6-6-536

13. Benyamini Y. Health and illness perceptions. In: Friedman H, editor. The Oxford Handbook of Health Psychology. Oxford: Oxford University Press. (2011). doi: 10.1093/oxfordhb/9780195342819.013.0013

14. Palominos PE, Gossec L, Kreis S, Hinckel CL, da Silva Chakr RM, Moro ALD, et al. The effects of cultural background on patient-perceived impact of psoriatic arthritis-a qualitative study conducted in Brazil and France. Adv Rheumatol. (2018) 58:1–4. doi: 10.1186/s42358-018-0036-6

15. Segal B, Pogatchnik B, Rhodus N, Sivils KM, McElvain G, Solid C. Pain in primary Sjögren's syndrome: the role of catastrophizing and negative illness perceptions. Scand J Rheumatol. (2014). 43:234–41. doi: 10.3109/03009742.2013.846409

16. Kotsis K, Voulgari PV, Tsifetaki N, Drosos AA, Carvalho AF, Hyphantis T. Illness perceptions and psychological distress associated with physical health-related quality of life in primary Sjögren's syndrome compared to systemic lupus erythematosus and rheumatoid arthritis. Rheumatol Int. (2014) 34:1671–81. doi: 10.1007/s00296-014-3008-0

17. Daleboudt G, Broadbent E, McQueen F, Kaptein A. Intentional and unintentional treatment nonadherence in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Care Res. (2012) 63:342–50. doi: 10.1002/acr.20411

18. Maas M, Taal E, van der Linden S, Boonen A. A review of instruments to assess illness representations in patients with rheumatic diseases. Ann Rheum Dis. (2009) 68:305–9. doi: 10.1136/ard.2008.089888

19. Løchting I, Fjerstad E, Garratt AM. Illness perceptions in patients receiving rheumatology rehabilitation: association with health and outcomes at 12 months. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. (2013) 14:28. doi: 10.1186/1471-2474-14-28

20. Milic V, Grujic M, Barisic J, Marinkovic-Eric J, Duisin D, Cirkovic A, et al. Personality, depression and anxiety in primary Sjogren's syndrome—association with sociodemographic factors and comorbidity. PLoS ONE. (2019) 14:e0210466. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0210466

21. Sawyer AT, Harris SL, Koenig HG. Illness perception and high readmission health outcomes. Heal Psychol Open. (2019) 6:2055102919844504. doi: 10.1177/2055102919844504

22. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. (2011). Available from: www.cochrane-pro-mg.org (cited Sep 23, 2018).

23. El Miedany Y, editor. Patient Reported Outcome Measures in Rheumatic Diseases. Switzerland: Springer (2016). p. 1–449. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-32851-5

24. Hammitt KM, Naegeli AN, Van Den Broek RWM, Birt JA. Patient burden of Sjögren's: a comprehensive literature review revealing the range and heterogeneity of measures used in assessments of severity. RMD Open. (2017) 3:e000443. doi: 10.1136/rmdopen-2017-000443

25. Prakash V, Shah S, Hariohm K. Cross-cultural adaptation of patient-reported outcome measures: a solution or a problem? Ann Phys Rehabil Med. (2019) 62:174–7. doi: 10.1016/j.rehab.2019.01.006

26. Epstein WV, Henke CJ. The nature of U.S. rheumatology practice, 1977. Arthritis Rheum. (1981) 24:1177–87. doi: 10.1002/art.1780240911

27. Fukuhara S, Bito S, Green J, Hsiao A, Kurokawa K. Translation, adaptation, and validation of the SF-36 Health Survey for use in Japan. J Clin Epidemiol. (1998) 51:1037–44. doi: 10.1016/S0895-4356(98)00095-X

28. Bowden A, Fox-Rushby JA. A systematic and critical review of the process of translation and adaptation of generic health-related quality of life measures in Africa Asia Eastern Europe the Middle East South America. Soc Sci Med. (2003) 57:1289–306. doi: 10.1016/S0277-9536(02)00503-8

29. Hendrikx J, De Jonge MJ, Fransen J, Kievit W, Van Riel PLCM. Systematic review of patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs) for assessing disease activity in rheumatoid arthritis. RMD Open. (2016) 2:1–9. doi: 10.1136/rmdopen-2015-000202

30. Stamm T, Van Der Giesen F, Thorstensson C, Steen E, Birrell F, Bauernfeind B, et al. Patient perspective of hand osteoarthritis in relation to concepts covered by instruments measuring functioning: a qualitative European multicentre study. Ann Rheum Dis. (2009) 68:1453–60. doi: 10.1136/ard.2008.096776

31. Gibbons C, Singh S, Gibbons B, Clark C, Torres J, Cheng MY, et al. Using qualitative methods to understand factors contributing to patient satisfaction among dermatology patients: a systematic review. J Dermatolog Treat. (2017). doi: 10.1080/09546634.2017.1364688

32. Gairy K, Ruark K, Sinclair SM, Brandwood H, Nelsen L. An innovative online qualitative study to explore the symptom experience of patients with primary Sjögren's Syndrome. Rheumatol Ther. (2020) 7:601–15. doi: 10.1007/s40744-020-00220-9

33. Lackner A, Ficjan A, Stradner MH, Hermann J, Unger J, Stamm T, et al. It's more than dryness and fatigue: the patient perspective on health-related quality of life in primary Sjögren's Syndrome—a qualitative study. PLoS ONE. (2017) 12:e0172056. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0172056

34. Stack RJ, Southworth S, Fisher BA, Barone F, Buckley CD, Rauz S, et al. A qualitative exploration of physical, mental and ocular fatigue in patients with primary Sjögren's Syndrome. PLoS ONE. (2017) 12:e0187272. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0187272

35. Hackett K, Deary V, Deane KHO, Newton JL, Ng W-F, Rapley T. “‘You look fine' they'll say”: a qualitative focus group study exploring the symptoms of fatigue, sleep disturbances and pain in primary Sjogren's syndrome and their impact on everyday life. Br J Occup Ther. (2017) 80(8_Suppl.):1–127. doi: 10.1177/0308022617724785

36. Ngo DYJ, Thomson WM, Nolan A, Ferguson S. The lived experience of Sjögren's Syndrome. BMC Oral Health. (2016) 16:7. doi: 10.1186/s12903-016-0165-4

37. Krueger RA, Anne CM. Focus Groups: A Practical Guide for Applied research. 5th ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publictions. (2014).

38. Tong A, Sainsbury P, Craig J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): a32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int J Qual Heal Care. (2007) 19:349–57. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/mzm042

40. van Tuyl LHD, Hewlett S, Sadlonova M, Davis B, Flurey C, Hoogland W, et al. The patient perspective on remission in rheumatoid arthritis: “You've got limits, but you're back to being you again”. Ann Rheum Dis. (2015) 74:1004–10. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2013-204798

41. Kvale S. Interviews—An Introduction to Qualitative Research Interviewing. USA, California: Sage. (1996).

42. ATLAS.ti Scientific Software Development GmbH. ATLAS. ti 8. Qualitative Data Analysis. (2019). Available from: http://www.atlasti.com/index.html (cited Jun 10, 2019).

43. World Health Organization. How to Use the ICF. A Practical Manual for Using the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF). Geneva (2013).

44. Prodinger B, Stucki G, Coenen M, Tennant A. The measurement of functioning using the international classification of functioning, disability and health: comparing qualifier ratings with existing health status instruments. Disabil Rehabil. (2017) 8288:1–8.

45. Cieza A, Fayed N, Bickenbach J, Prodinger B. Refinements of the ICF linking rules to strengthen their potential for establishing comparability of health information. Disabil Rehabil. (2019) 41:574–83. doi: 10.3109/09638288.2016.1145258

46. Herrera A, Sánchez G, Espinoza I, Wurmann P, Bustos C, Leiva L, et al. Illness experiences of chilean women with sjögren's syndrome from the patient perspective. Arthritis Care Res. (2020) 73:1210–18. doi: 10.1002/acr.24256

47. Rojas-Alcayaga G, Herrera Ronda A, Espinoza Santander I, Bustos Reydet C, Ríos Erazo M, Wurmann P, et al. Illness experiences in women with oral dryness as a result of Sjögren's Syndrome: the patient point of view. Musculoskeletal Care. (2016) 14:233–42. doi: 10.1002/msc.1134

48. Puchner R, Vavrovsky A, Pieringer H, Hochreiter R. The supply of rheumatology specialist care in real life. Results of a nationwide survey and analysis of supply and needs. Front Med. (2020) 7:16. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2020.00016

49. Dejaco C, Lackner A, Buttgereit F, Matteson EL, Narath M, Sprenger M. Rheumatology workforce planning in western countries: a systematic literature review. Arthritis Care Res. (2016) 68:1874–82. doi: 10.1002/acr.22894

50. Ritschl V, Lackner A, Boström C, Mosor E, Lehner M, Omara M, et al. I do not want to suppress the natural process of inflammation: new insights on factors associated with non-adherence in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Res Ther. (2018) 20:1–11. doi: 10.1186/s13075-018-1732-7

51. Unger J, Mattsson M, Drǎgoi RG, Boström C, Buttgereit F, Lackner A, et al. Experiences of people with Primary Sjögren's Syndrome in daily life: a multicentre qualitative European study. Poster: Jahrestagung der Österreichischen Gesellschaft für Rheumatologie & Rehabilitation 29. November-1. Dezember 2018, Tech Gate Wien. J Miner Muskuloskelet Erkrankungen. (2018) 25:118–42. doi: 10.1007/s41970-018-0050-5

Keywords: Sjögren's syndrome, quality of life, PROMs, focus group technique, psychological impact, social impact, physical impact, ICF

Citation: Unger J, Mattsson M, Drăgoi RG, Avram C, Boström C, Buttgereit F, Lackner A, Witte T, Raffeiner B, Peichl P, Durechova M, Hermann J, Stamm TA and Dejaco C (2021) The Experiences of Functioning and Health of Patients With Primary Sjögren's Syndrome: A Multicenter Qualitative European Study. Front. Med. 8:770422. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2021.770422

Received: 03 September 2021; Accepted: 05 October 2021;

Published: 18 November 2021.

Edited by:

Rosaria Talarico, University of Pisa, ItalyReviewed by:

Alen Zabotti, Università degli Studi di Udine, ItalyDaniela Costa, Universidade NOVA de Lisboa, Portugal

Copyright © 2021 Unger, Mattsson, Drăgoi, Avram, Boström, Buttgereit, Lackner, Witte, Raffeiner, Peichl, Durechova, Hermann, Stamm and Dejaco. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Tanja A. Stamm, tanja.stamm@meduniwien.ac.at orcid.org/0000-0003-3073-7284

Julia Unger

Julia Unger Malin Mattsson

Malin Mattsson Răzvan G. Drăgoi5

Răzvan G. Drăgoi5  Claudiu Avram

Claudiu Avram Carina Boström

Carina Boström Frank Buttgereit

Frank Buttgereit Angelika Lackner

Angelika Lackner Torsten Witte

Torsten Witte Bernd Raffeiner

Bernd Raffeiner Josef Hermann

Josef Hermann Tanja A. Stamm

Tanja A. Stamm Christian Dejaco

Christian Dejaco