- 1Department of Biochemistry, Cancer Biology, Neuroscience and Pharmacology, School of Graduate Studies and Research, Meharry Medical College, Nashville, TN, United States

- 2Bioinformatics Core, School of Graduate Studies and Research, Meharry Medical College, Nashville, TN, United States

The expression of the melanoma/cancer-testis antigen MAGEC2/CT10 is restricted to germline cells, but like most cancer-testis antigens, it is frequently upregulated in advanced breast tumors and other malignant tumors. However, the physiological cues that trigger the expression of this gene during malignancy remain unknown. Given that malignant breast cancer is often associated with skeletal metastasis and co-morbidities such as cancer-induced hypercalcemia, we evaluated the effect of high Ca2+ on the calcium-sensing receptor (CaSR) and potential mechanisms underlying the survival of triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC) cells at high Ca2+. We show that chronic exposure of TNBC cells to high Ca2+ decreased the sensitivity of CaSR to Ca2+ but stimulated tumor cell growth and migration. Furthermore, high extracellular Ca2+ also stimulated the expression of early response genes such as FOS/FOSB and a unique set of genes associated with malignant tumors, including MAGEC2. We further show that the MAGEC2 proximal promoter is Ca2+ inducible and that FOS/FOSB binds to this promoter in a Ca2+- dependent manner. Finally, downregulation of MAGEC2 strongly inhibited the growth of TNBC cells in vitro. These data suggest for the first time that MAGEC2 is a high Ca2+ inducible gene and that aberrant expression of MAGEC2 in malignant TNBC tissues is at least in part mediated by an increase in circulating Ca2+ via the AP-1 transcription factor.

Introduction

Triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC) remains the most aggressive and hard-to-treat breast cancer subtype due in part to lack of estrogen and progesterone receptors (ER, PR), as well as the human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2). Although the aggressiveness of the disease is more frequently diagnosed in younger and patients of African ancestry compared to Caucasian patients (1, 2), the underlying causes remain controversial. One of the most debilitating systemic cancer-associated changes that develop as breast and other solid cancers progress to more malignant and metastases-prone disease stages, is cancer-induced hypercalcemia (CIH). This often, overlooked abnormal increase in circulating Ca2+ is more likely to occur in at least 80% of patients with metastatic breast cancer due to the development of secondary disease lesions in the calcium-rich skeletal tissues (3–5). CIH may also develop in patients with rapidly growing tumors without evidence of bone metastasis due to increased secretion of parathyroid hormone-related protein (PTHrP) by the tumor cells (6, 7). In either case, the stimulation of osteoclast activity by tumor cell-derived PTHrP and other osteolytic factors leads to increased bone resorption and, eventually, increased circulating Ca2+ or CIH (8). Even though frequently diagnosed as mild or non-life-threatening, high circulating Ca2+ levels (>10.3 mg/dL) in breast cancer patients have been shown to be associated with aggressive tumors in premenopausal women (9) and larger tumors in post-menopausal women (10). While this suggests that hypercalcemia drives breast cancer progression, this notion and the underlying mechanisms remain poorly understood.

At the center of the Ca2+ sensing/signaling system is the ubiquitous cell surface Ca2+ sensor, the calcium-sensing receptor (CaSR), which is activated by slight increases in extracellular Ca2+ as well as other divalent cations and plays a central role in Ca2+ homeostasis (11, 12). Activation of the CaSR not only modulates the expression and/or activity of Ca2+ activated and Ca2+ binding proteins (13), but also the biosynthesis and secretion of osteolytic factors such as PTHrP (14). Like most stress conditions, an increase in circulating Ca2+ triggers the expression of early response genes such as c-FOS and EGR1 (15) which in turn may lead to the expression of genes involved in tumor progression. In addition to cell type-specific differences in the expression level of CaSR (16, 17), the activity of this receptor has also been shown to be modulated by specific mutations, including inactivating mutations in exon 7 of the receptor in breast cancer patients (18, 19). However, whether the expression levels, the activity of the CaSR, or both is sufficient to drive distinct proliferation and/or migration patterns of certain breast tumor cells at high Ca2+ remains unknown.

The melanoma associated antigen C2 (MAGEC2/CT10) is one of 60 identified cancer germline antigens that were previously described as cancer-testis antigens (20). MAGEC2, has been shown to be aberrantly expressed in squamous cell carcinomas, melanomas, sarcomas, myelomas, hepatocellular carcinomas, lung carcinoma, prostate adenocarcinoma, and breast carcinoma (20–22). Accumulating evidence suggests that MAGEC2 influences the progression and metastasis of breast cancer and other solid tumors (21–25) by mechanisms that include the promotion of epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (23, 24), p53 stability (26) and stabilization of the activated form of STAT3 (27). Detection of MAGEC2/CT10 in patient tissues has also been shown to be an independent predictor of lymph node metastasis and recurrence of prostate cancer (22). To date, however, the physiological cues and the mechanisms underlying the increase in expression of this and related genes in malignant tissues remain unclear.

In this study, we sought to determine the effect of sustained high Ca2+ on the growth and motility of TNBC cells and to delineate the mechanism(s) underlying the increase in cell migration and proliferation at high extracellular Ca2+. We show that chronic exposure of TNBC cells to high extracellular Ca2+ led to a decrease in the sensitivity of the CaSR to Ca2+ but rather stimulated tumor cell growth and migration. Interestingly, high extracellular Ca2+ transiently induced the expression of early response genes that in turn induced the expression of genes including MAGEC2 that drive the growth and motility of the tumor cells. Overall, this study suggests that the aberrant expression of MAGEC2 and presumably related cancer-testis antigens in malignant solid tumors is triggered at least in part by the gradual increase in circulating Ca2+ that develops as breast cancer progresses to more malignant stages.

Materials And Methods

Cell Lines and Cell Culture

The breast epithelial cell lines 184A1 and MCF-10A, as well as the breast cancer cell lines MDA-MB-231, MDA-MB-468, BT-549, HCC38, HCC70, HCC1937, and HCC1806, were purchased from the American Tissue Type collection (East Rutherford, New Jersey, United States). The primary human breast epithelial cells (HMEC) were a gift from Dr. Jennifer Pietenpol (Vanderbilt Ingram Cancer Center). The cells were maintained in media and supplements recommended by the supplier and, except otherwise indicated, were supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS, R & D Systems), 10 mM NaHCO3, and Penicillin and Streptomycin, in a humidified incubator at 37°C, 5% CO2. The cells were passaged every 2-3 days.

Microarray Experiments and Analyses

Total RNA was extracted from cells cultured in complete medium or complete medium supplemented with 3.0 or 5.0 mM Ca2+ for 48 h using the RNeasy kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA). For microarray expression analysis, the quality of RNA samples was assessed using an Agilent Bioanalyzer. Target generation was performed by using the Ambion WT Sense reaction kit from Affymetrix and following the manufacturer’s protocol with 130 ng of intact RNA. The cDNA target was then enzymatically fragmented and end-labeled using the Affymetrix labeling reagents following manufacturer’s protocols. The cRNA, cDNA, and fragmented and end-labeled targets were assessed by Agilent bioanalysis to ensure that the amplified targets met the recommended smear range and to also assess whether fragmentation and end-labeling were complete. Only samples with a high RNA integrity number (RIN) number (>7) were used for hybridization. For Gene expression arrays, the requisite amount of target was added to the hybridization cocktail to give a final target concentration of ~25 ng/µl in the hybridization cocktail for a total of 2.5µg of fragmented targets hybridized to each array. The targets in hybridization cocktail were heat denatured, centrifuged, and then loaded on the human gene 2.0ST Affymetrix cartridge array and hybridized overnight in an Affymetrix Model 645 Hybridization Oven. After hybridization, the cartridge arrays were washed, and stained per standard Affymetrix protocols using an Affymetrix Fluidics Station 450. The arrays were then scanned in an Affymetrix 7G plus scanner and the resulting data were analyzed by Affymetrix Expression Console v.1.2 using an Robust Multi-array Average (RMA) normalization algorithm producing log base 2 results. Differential gene expression was assessed between replicate groups (n=4) using a moderated t-test and Benjamini-Hochberg multiple testing correction, with significance determined by adjusted p-value <0.05 and absolute value fold change >2.0. Hierarchical clustering was performed in GeneSpring on both averaged and non-averaged normalized expression values. Microarray datasets have been deposited and made available on the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) database with the accession number GSE189520 (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GSE189520).

Reverse Transcriptase and Real-Time PCR

For the validation of the identified genes, total RNA was isolated from selected breast cancer cells treated with complete medium supplemented with high Ca2+ (5.0 mM) for the indicated times. Control cells were those maintained in complete medium (~1.3 mM Ca2+) for the duration of the experiment. First-strand cDNA synthesis was performed using the iScript cDNA synthesis kit (BioRad) following the protocol provided by the manufacturer. This was followed by semiquantitative real-time PCR using individual TaqMan gene expression assays (Table S1) and TaqMan gene expression master mix (Life Technologies).

Downregulation of MAGEC2/CT10 and FOS/FOSB in BT-549 Cells

Short hair-pin RNA (shRNA) directed against MAGEC2/CT10 in plasmid pGIPZ (Open Biosystems) were purchased from Thermofisher (Calsbad, CA). The plasmid DNA was purified using endofree maxiprep kits (Qiagen) and equal amounts (20 µg/10 cm dish) of the MAGEC2, c-FOS or FOSB and non-silencing scramble control (SCR) were used for transfection of BT-549 cells as previously described (28). Cells were sorted and/or selected with puromycin (2 µg/ml) for at least 10 days before use in experiments. The expression of MAGEC2/CT10, FOS, and FOSB was assessed by semi-quantitative RT-PCR and western blotting.

Immunoblotting

Whole cell extracts were prepared in RIPA buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, 1% NP-40, 0.1% sodium deoxycholate, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA and 1x protease inhibitor cocktail (Sigma) as previously described (29). Equal amounts of cleared lysates were separated in 4-12% NuPage gels (Invitrogen), transferred to nitrocellulose membranes, and probed with the indicated primary antibodies as previously described (29). Blots were revealed by enhanced chemiluminescence (Perkin Elmer). The expression of GAPDH or β-actin was used as an internal standard. The following antibodies were used: MAGEC2 (Abcam, Cambridge, MA), β-actin (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO), Total ERK2, GAPDH, and CaSR (Santa Cruz Biotechnology Inc. Santa Cruz, CA), phospho-ERK1/2, c-Fos, and FosB (Cell Signaling Technology).

Cell Proliferation and Migration Assays

Cells were plated into 24-well flat-bed plates at a density of 2 × 103 cells per well in triplicate then incubated in medium containing high Ca2+ (5.0 mM) for up to 7 days with the culture medium changed every 3 days. At the end of each time point, PrestoBlue reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) was diluted 1:10 in HBSS supplemented with 0.5 mM Ca2+ and 0.5 mM Mg2+ or the corresponding base medium for each cell line. The culture medium was aspirated and replaced with 100 µl of diluted reagent per well, followed by incubation at 37°C for up to 3 h. The proliferation and viability of the cells was determined by measuring the fluorescence according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Invitrogen). Cell migration was carried out in Boyden chambers as previously described (28). Migrated cells were fixed in 3.7% formaldehyde, then stained with crystal violet and counted.

Genotyping of BC Cell Lines

Exponentially growing (60–80% confluency) breast cancer cells were harvested by scraping and were washed in ice-cold PBS. Cell pellets were either flash frozen at -80°C or used to isolate genomic DNA using the DNeasy blood and tissue DNA isolation kit (Qiagen). For determination of the CASR genotype, a 524 bp fragment containing the rs1801725, rs1042636, and rs1801726 loci in exon 7 of the receptor was amplified using Phusion High Fidelity PCR master mix (New England Biolabs) and the following primers: CASR-F CGAGGAGGTGCGTTGCAGCA and CaSR-R CCTCTGGCCGCTGGTCTCCA. Sequencing was performed using the ABI 3100 Genetic Analyzer according to the manufacturer’s protocol and read using sequence scanner version 2 (Applied Biosystems).

Chromatin Immunoprecipitation

Cells were grown to 70-80% confluency, treated with or without high Ca2+ for 2, 4 or 48 h, and processed for ChIP assays using the ChIP Express IT kit according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Active Motif). Briefly, cells were fixed using 3.7% formaldehyde in PBS for 15 minutes at room temperature, then quenched with 100 mM glycine in PBS for 5 min and harvested by scrapping into ice-cold PBS. Cell lysates were enzymatically sheared using micrococcal nucleases, and the cleared lysates immunoprecipitated using antibodies against c-Fos or FosB (Cell Signaling Technology). After reversal of the cross-links, the associated DNA fragments were purified in spin columns and equal amounts used for semi-quantitative real-time PCR using primers targeting the MAGEC2 promoter (accession number: NM_016249.3).

Luciferase Assays

The proximal MAGEC2 promoter including 90 bp downstream the transcription start site (-1008 - +90) was truncated by PCR and designated C2-P1 to C2-P5 as depicted in Figure 6A. Primers included a 5’ Hind III and 3’ Xho I restriction enzymes (Thermo Fisher Scientific). The truncated promoter segments were amplified from MCF-10A genomic DNA using Phusion High Fidelity PCR master mix (New England Biolabs), digested with the restriction enzymes, and cleaned using a DNeasy plasmid purification kit (Qiagen). The fragments were cloned into Hind III/Xho I digested and purified promoter-less pGL4 luciferase reporter vector (Promega). Cloning of the MAGEC2 promoter fragments was verified by restriction enzyme digestion and DNA sequencing. For luciferase assays, the MAGEC2 truncated promoter constructs and a control vector expressing Renilla luciferase were transfected into 293T cells in 6-well plates using Lipofectamine 3000 (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). Cells were cultured overnight at 37°C, media was changed the following day to complete medium with or without the indicated concentrations of Ca2+ and incubated for the indicated times. The cells were lysed using RIPA buffer, and luciferase activity was assessed by using the dual luciferase assay kit and analyzed following the manufacturer’s instructions (Promega). Renilla luciferase activity was used as the transfection control.

Statistical Analysis

Data were analyzed using an unpaired t-test. If more than two groups were compared, one-way and two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) were performed using GraphPad Prism (San Diego, CA, USA). For all statistical analyses p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Significance of CaSR Variants in the Growth and Sensitivity of Breast Cancer Cells to High Ca2+

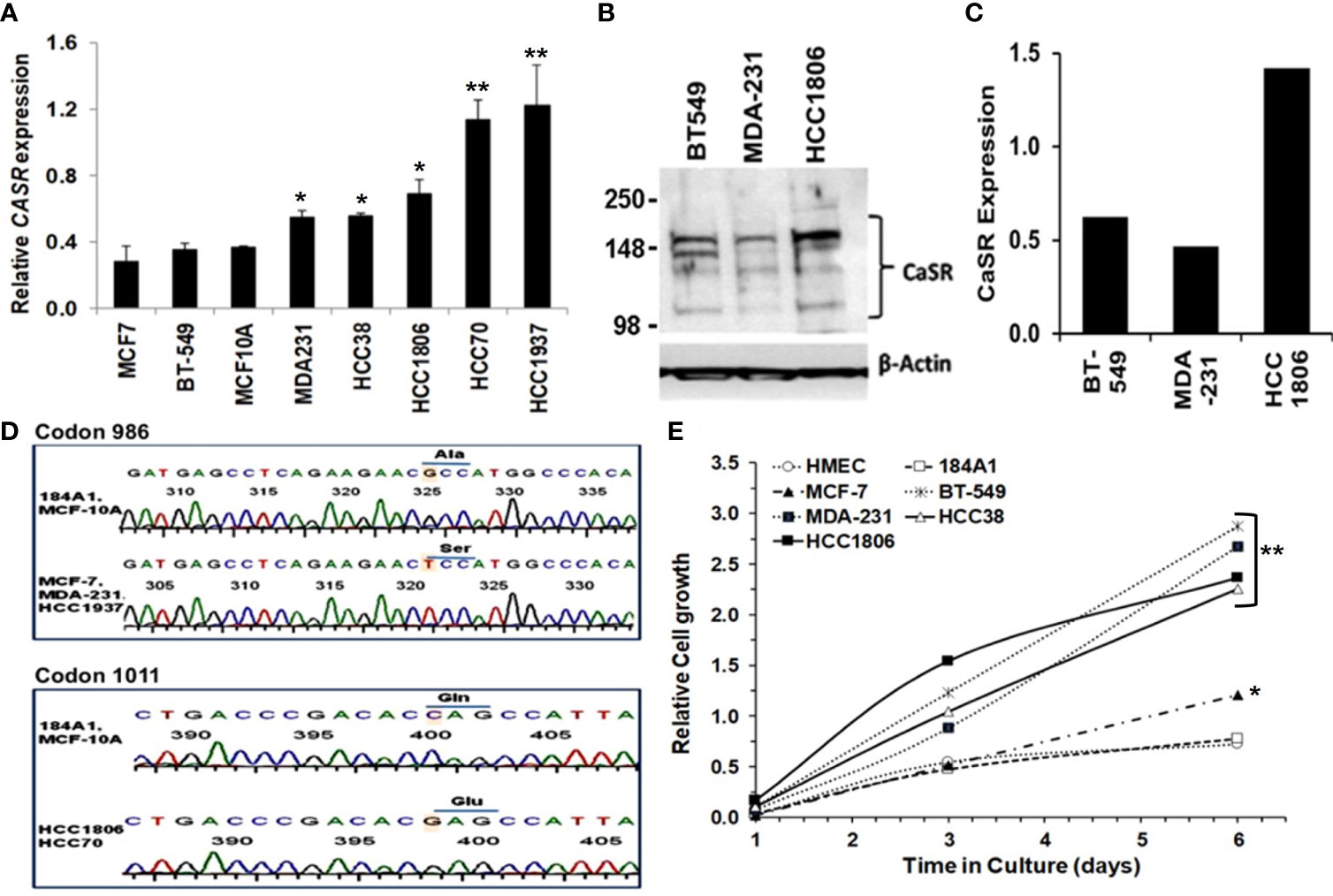

Most normal and malignant cell types that express the CaSR respond to extracellular Ca2+ as a first messenger to elicit cellular functions such as growth and motility (30, 31). The Ca2+ threshold for cell lines is quite distinct from that in living individuals due to the existence of an elaborate Ca2+ homeostatic system (32, 33). Consequently, high circulating ionized Ca2+ in vivo, is depicted as Ca2+ concentrations above the normal Ca2+ concentration of ~1.3 mM (4.4-5.2 mg/dL). In the case of cell lines and heterologous expression of the CaSR, Bai et al., showed that the effective concentration (EC50) of Ca2+ as an agonist for the CaSR overexpressed in HEK293 cells was ~4.1 mM (33). In the studies described herein, 3.0 and 5.0 mM Ca2+ concentrations were routinely used as high Ca2+ for TNBC cells. Thus using normal breast epithelial and a diverse set of breast cancer cell lines, we demonstrate that the expression of the CaSR at the mRNA level (Figure 1A) is cell type specific. We next confirmed this at the protein level in BT-549, MDA-MB-231 and HCC1806 TNBC cell lines (Figures 1B, C).

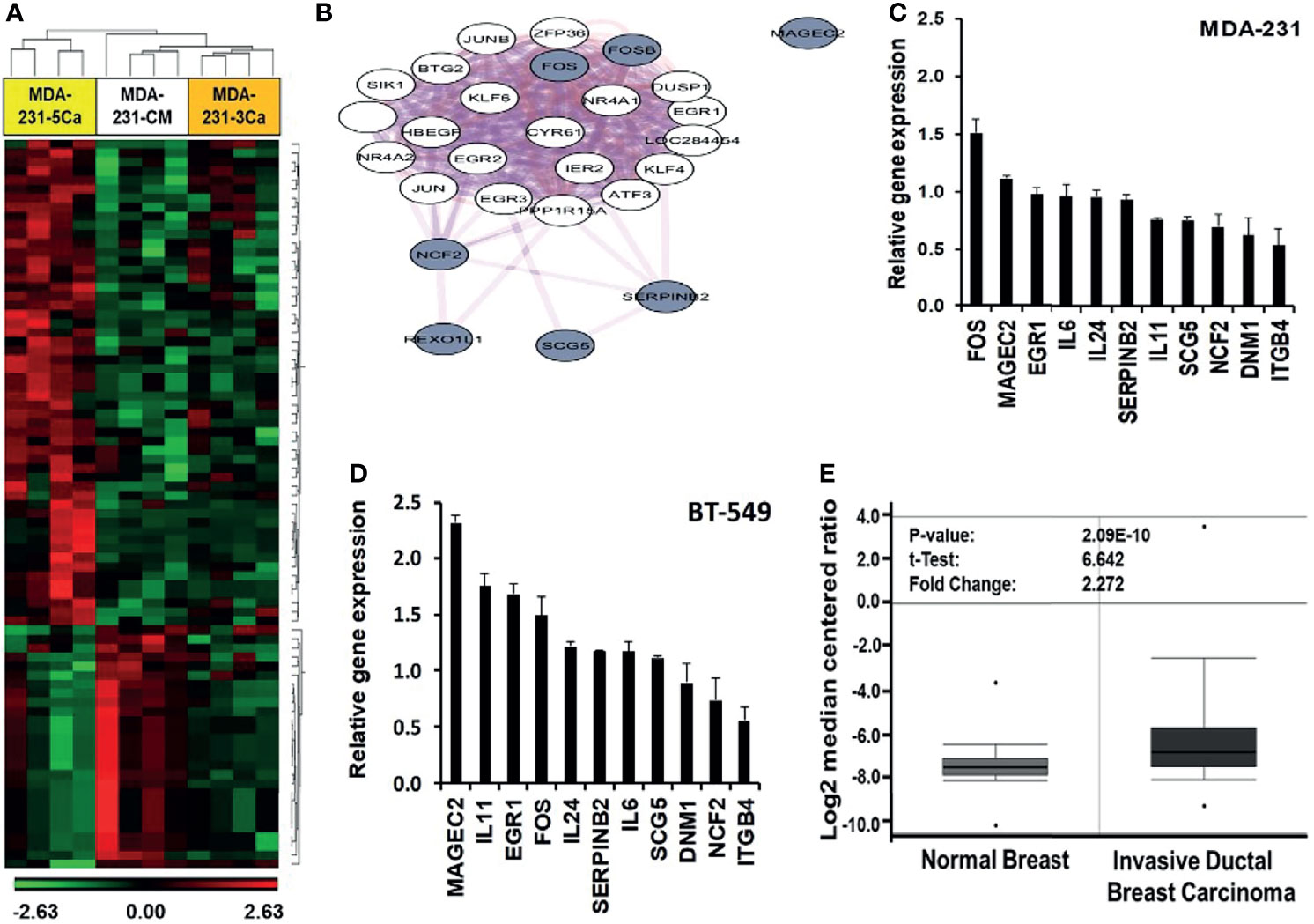

Figure 1 Significance of CaSR variants in the growth and sensitivity of breast cancer cells to high Ca2+. (A) Expression of CASR in breast epithelial and breast cancer cell lines was assessed by reverse transcriptase and real-time PCR (RT-PCR). (B, C) Basal expression of CaSR in the indicated breast cancer cells was assessed by western blotting (B) and quantified by using the NIH ImageJ software (C). (D) Genotyping of exon 7 mutations in breast epithelial and breast cancer cells by DNA sequencing of a 524 bp fragment. Shown are chromatograms depicting changes of the nucleotide sequence at codons 986 (Ala to Ser) and 1011 (Gln to Glu). (E) Effect of high Ca2+ on the growth of breast epithelial and breast cancer cells in vitro. Cell proliferation/viability was assessed by using the PrestoBlue cell viability reagent. * denotes p < 0.05, ** denotes p < 0.01.

Given that polymorphisms at codons 986 (rs1801725) and 1011 (rs1801726) alter the sensitivity of the receptor to Ca2+ and are associated with high circulating Ca2+ (18, 19, 34), we sought to determine the genotype of the receptor at these loci in established breast epithelial and breast cancer cell lines. As depicted in Figure 1D and Table 1, normal breast epithelial cell lines such as MCF-10A and 184A1 express the wild type receptor at both codons, while breast cancer cell lines express the wild type (e.g. BT-549), the A986S (MCF-7, MDA-MB-231) or the Q1011E (HCC1806, HCC70) mutant receptors.

Table 1 Calcium-sensing receptor Exon 7 variants in normal breast epithelial and breast cancer cells.

To determine whether the combination of the expression level and the genotype of the CaSR at the rs1801725 or rs1801726 locus influenced their proliferation at high Ca2+, we cultured the indicated breast cells lines in culture medium containing 5.0 mM Ca2+ for up to 6 days. Analysis of the cell viability revealed that most triple-negative breast cancer cells lines (MDA-231, BT-549, HCC1806, and HCC38) with wild-type or mutant CaSR (A986S or Q1011E) grew more efficiently at high Ca2+ than the luminal-A MCF-7 cell line which expresses low levels of the A986S mutant receptor. Likewise, immortalized normal breast epithelial cells or primary human mammary epithelial cells (184A1, HMEC) grew less efficiently at high Ca2+ (Figure 1E). To determine if the differences in the growth of these cells was associated with their response to transient increases in Ca2+, we compared the response of the A986S expressing MCF-7 and MDA-MB-231 cells to high Ca2+ by Ca2+ spectrofluorimetry. This analysis revealed that the amplitude of intracellular Ca2+ transients in response to high Ca2+ (3.0 mM) in MCF-7 cells was larger than that in MDA-MB-231 or MCF-10A cells (Figure S1A). Similarly, the amplitude of intracellular Ca2+ transients in the basal-like TNBC cell line HCC38 was larger than that of the HCC1806 (Figure S1B). We also assessed the viability/proliferation of the indicated breast epithelial and breast cancer cells at high Ca2+ and showed that the viability of MCF 7 cells was strongly impacted at high Ca2+ (Figure S1C). Based on these data, it is plausible to suggest that the decrease in the viability/proliferation of MCF-7 cells at high Ca2+ could be due to the more intense intracellular Ca2+ surge. However, these data also suggest that the expression level, the mutational status in exon 7 of the CaSR and the amplitude of intracellular Ca2+ transients in response to high extracellular Ca2+, is cell type specific.

High Calcium Adaptation of Breast Cancer Cells Is Associated With Reduced Sensitivity of CaSR to Extracellular Ca2+ But Promotes Cell Growth and Motility

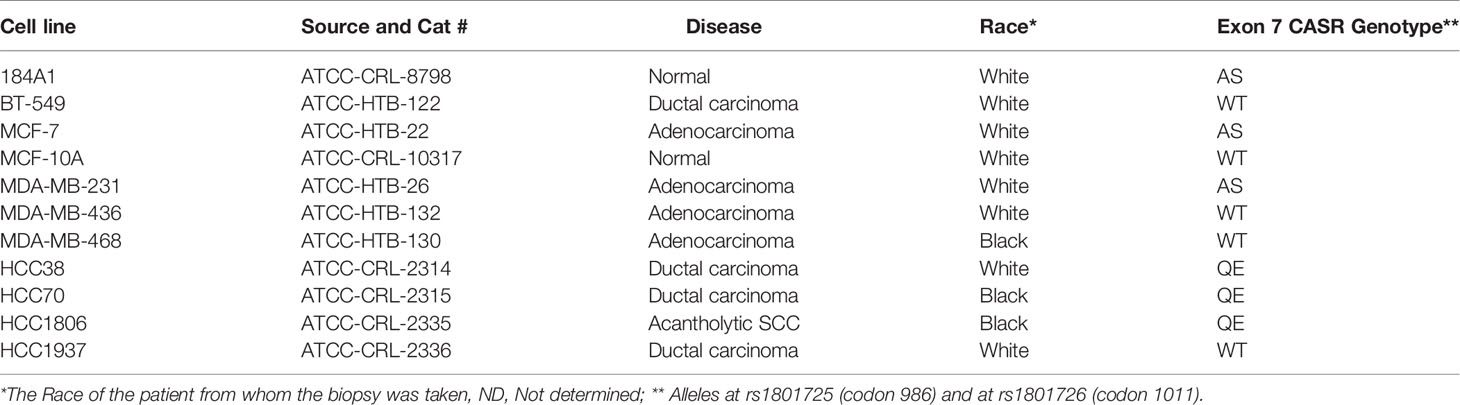

Up to 80% of advanced breast cancers are known to spread to Ca2+ rich skeletal tissues (4). To determine whether TNBC cells acquire tolerance to sustained high Ca2+, MDA-MB-231 cells were maintained in normal growth medium supplemented without or with 3.0 or 5.0 mM Ca2+ herein referred to as 3Ca and 5Ca cells respectively, for >6 passages over a six-week period (Figures S2A, B). Parental and the Ca2+ adapted cells were then tested for their ability to respond to high Ca2+ or EGF using the activation of MAP kinase ERK1/2 by western blotting as the read out (28, 35). Figure 2A reveals that the CaSR protein levels did not noticeably change following the continuous growth of MDA-MB-231 cells at high Ca2+. EGF-induced activation of ERK1/2 was not only robust, but also unaffected by the prolong culture of these cells at high Ca2+ (Figure 2B). However, transient (10 min) treatment of the parental cells with high Ca2+ (5.0 mM) led to a strong (5.5 fold) activation of ERK1/2, while a similar treatment of the 3.0 mM Ca2+- and 5.0 mM Ca2+-adapted cells led to a 3.5 fold and 1.7 fold change in the activation of ERK1/2 respectively, relative to control (Figures 2B, C). Collectively, these data demonstrate that while the CaSR protein levels remain unchanged, there is possibly desensitization of the CaSR to high Ca2+, leading to the downstream affects depicted by altered ERK activation.

Figure 2 High calcium adaptation of breast cancer cells is associated with reduced sensitivity of CaSR to extracellular Ca2+ but promotes cell growth and motility. (A) MDA-MB-231 cells were cultured in complete medium supplemented with 3.0 or 5.0 mM Ca2+ for up to 6 weeks. The expression of CaSR in the Ca2+ adapted cells was assessed by western blotting; β-actin was used as the loading control. (B) The Control, 3.0 and 5.0 mM Ca2+ adapted MDA-MB-231 cells were treated with EGF (50 ng/ml) or high Ca2+ (5.0 mM) for 10 mins and the activation of ERK1/2 assessed by western blotting. (C) The protein bands representing phosphorylated ERK1/2 were quantified by using the NIH ImageJ. Bares represent active ERK1/2 relative to untreated control from independent experiments. (D, E) Control, 3.0 and 5.0 mM Ca2+ adapted MDA-MB-231 cells were seeded at 1000 cells/well in 96 well plates on growth factor reduced Matrigel and cultured in complete medium for up to 10 days. Cell colonies were captured microscopically using a digital camera (D) and colony sizes were assessed by manually counting the cells in each colony (E). (F) Migration of Ca2+ adapted cells. Control, 3.0 and 5.0 mM Ca2+ adapted MDA-MB-231 cells in serum free medium were cultured for 24 h in Boyden chamber inserts and serum free medium containing 5.0 mM Ca2+ was used as the chemoattractant. Shown are the migrated cells/field from at least three independent fields. * denotes p < 0.05, ** denotes p < 0.01.

We next assessed whether sustained high Ca2+ altered the ability of parental and high Ca2+ adapted MDA-MB-231 cells to form colonies in 3D cultures. Consistent with data in Figure 1E, the high Ca2+-adapted cells formed larger colonies compared to the parental cells (Figure 2D) and the extent of growth was Ca2+ concentration-dependent (Figure 2E). We also analyzed the ability of the high Ca2+ adapted cells to migrate in Boyden chambers by using serum free medium supplemented with 5.0 mM Ca2+ as the chemoattractant. Figure 2F and Figure S2C, show that compared to parental MDA-MB-231 cells, the 3.0 or 5.0 mM Ca2+-adapted cells showed a >4 fold ability to migrate in response to high Ca2+. Together, these data suggest that breast cancer cells adapt to high prevailing Ca2+ levels via reduced sensitivity of CaSR to the sustained high extracellular Ca2+, and that the high Ca2+ adapted cells are more efficient in migration and/or growth at high Ca2+. Together with data in Figure 1, these data support the notion that the physiological impact of high Ca2+ in various breast cancer cells may depend on the high Ca2+ modulated Ca2+ influx presumably via non-selective Ca2+ channels (36) and/or high Ca2+ modulated effectors downstream of the CaSR.

Induction of Early Response and Malignancy Associated Genes in Breast Cancer Cells in Response to High Ca2+

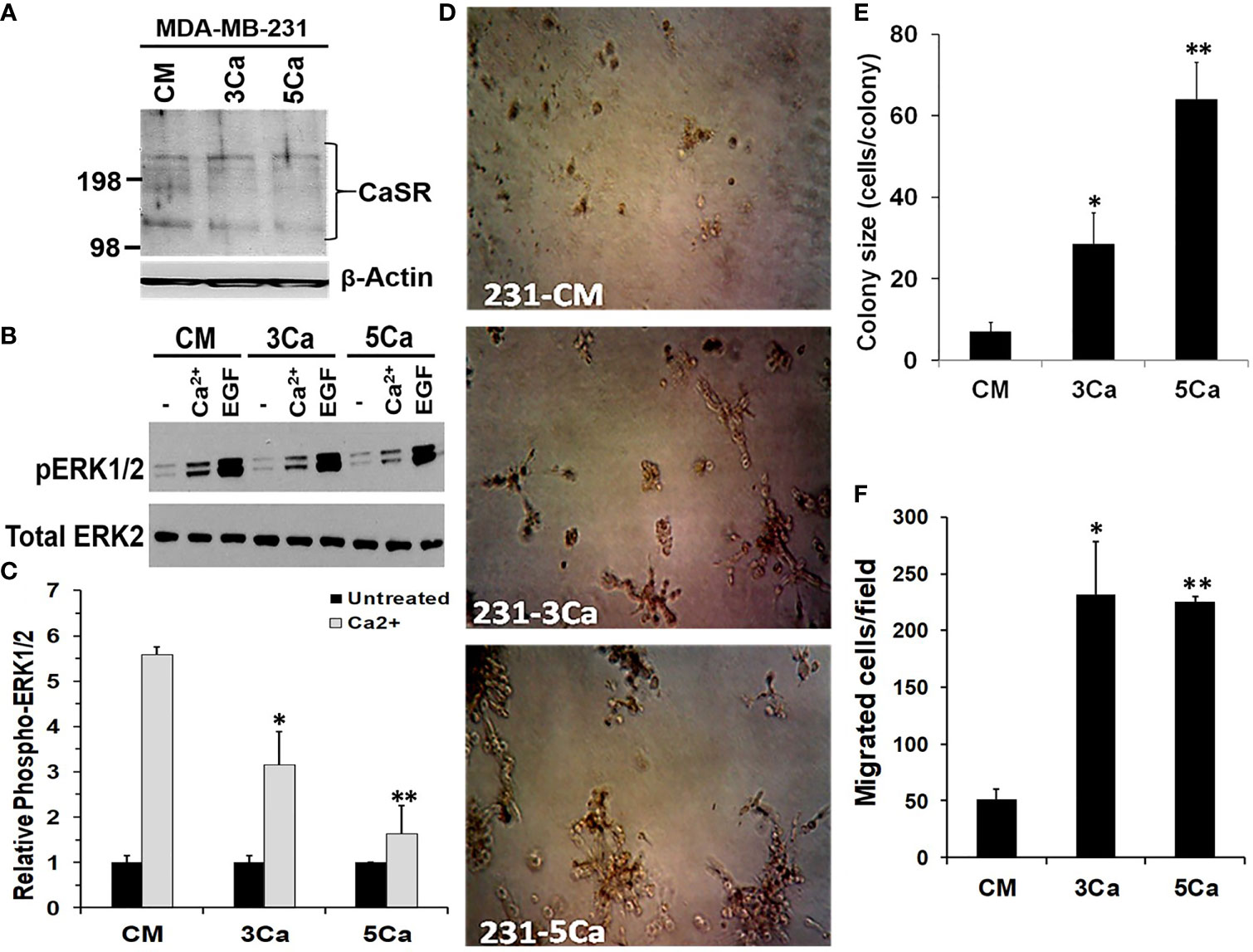

Previous studies revealed that breast cancer cells respond to acute increases in extracellular Ca2+ by up regulation of early response genes such as FOS and EGR1 (15, 37). This prompted us to speculate that a decrease in the activity of the CaSR as depicted in Figure 2 is not sufficient to explain the strong adaptive response of invasive breast cancer cells to sustained or breast cancer induced progressive increases in circulating Ca2+ in patients. To better understand the mechanism by which certain breast cancer cells acquire tolerance to high Ca2+, we performed genome-wide gene expression profiling using MDA-MB-231 cells. As shown in Table 1, MDA-MB-231 cells express the A986S variant of the CaSR. The MDA-MB-231 cells were cultured in complete medium supplemented without (CM, complete medium) or with either 3.0 or 5.0 mM Ca2+ for 48 hrs. Total RNA was extracted, hybridized on to Affymetrix Hu Gene 2.0 gene chips and the microarrays analyzed as described in materials and methods. From this analysis we observed that exposure of cells to 3.0 mM Ca2+ affected about 180 genes and that about 555 genes were affected by culturing the cells at 5.0 mM Ca2+ compared to the CM control. Of the differentially expressed genes in cells cultured at 5.0 mM Ca2+, at least 111 genes were up-regulated and 69 genes were downregulated at +/- 1.5 fold and p < 0.05 (Figure 3A).

Figure 3 Induction of early response and malignancy associated genes as a response of breast cancer cells to sustained high Ca2+. (A) Heatmap of Gene expression profiling of high Ca2+ treated MDA-MB-231 cells. (B) Biological network relationship of up regulated (high Ca2+ inducible) genes (hashed nodes), pink edges are physical interactions and purple edges are co-expression associations (https://genemania.org/). (C, D) Validation of high Ca2+ inducible genes by RT-PCR in MDA-MB-231 (C) and BT-549 (D) TNBC cells. (E) Expression of MAGEC2 in normal breast (n = 61) and invasive ductal breast carcinoma (n = 396) was analyzed in the TCGA Breast dataset in oncomine.

In addition to the early response genes (FOS, FOSB), MAGEC2 (CT10), SERPINB2 (PAI-2), NCF2, SCG5, IL11, IL24 and IL6 were among the most up-regulated genes (Table S2) while DNM1 and ITGB4 were among the most down-regulated genes (Table S3). Analysis of pathways affected by the culture of TNBC cells at high Ca2+ revealed significant modulation of cancer related pathways such as senescence and autophagy, cytokine and inflammatory response, TGF-β signaling, energy metabolism, as well as regulation of epigenetic stress (Table S4).

To determine the known relationships of these genes in specific pathways, Figure 3B demonstrates that most of the high Ca2+ inducible genes (hashed nodes) have already been demonstrated as Ca2+ activated/dependent genes. Among these genes, the expression of SERPINB2 (PAI-2) has been demonstrated to be Ca2+-dependent (38, 39) and the expression of PAI-2 has been shown to correlate with prolonged overall and disease-free survival of breast cancer patients as well as sensitivity to treatment with tamoxifen (40–42). Figure 3B also shows that although MAGEC2 is known to be upregulated in malignant forms of many cancers (21–23, 25, 43), its function as a Ca2+ modulated protein has not been demonstrated. Analysis of interactions with other high Ca2+ inducible genes revealed that it interacts with the high Ca2+ inducible SSX1 (Figure S3), a member of the SSX family of transcriptional repressors.

The effect of high Ca2+ on the expression of these genes was validated by semi-quantitative RT-PCR using individual Taqman gene expression assays (Table S1) and total RNA isolated from MDA-MB-231 and BT-549 (Figures 3C, D), as well as from HCC1806 and MCF-7 (Figure S4) breast cancer cell lines. Consistent with the molecular heterogeneity of breast cancer, this analysis revealed that high Ca2+-induced expression of early response genes FOS/FOSB as well as genes associated with malignant tumors such as MAGEC2 was cell type specific. Interestingly, MCF-7 cells that express relatively low levels of the A986S mutant CaSR and are sensitive to high Ca2+, did not show significant upregulation of FOS or MAGEC2 (Figure S4). Meanwhile, the expression of MAGEC2 was strongly induced by high Ca2+ in BT-549 cells (Figure 3C) and only modestly in MDA-MB-231 cells (Figure 3D). To assess the clinical relevance of this finding, we show that MAGEC2 is significantly upregulated in invasive ductal carcinoma tissues compared to normal breast tissues according to TCGA Breast dataset in oncomine (Figure 3E). Interestingly, the expression status of MAGEC2 is strongly associated with the relapse-free survival of basal-like breast cancer patients and has little or no effect on the relapse-free survival of ER positive or ER negative breast cancer subtypes (Figure S5).

MAGEC2 Is a High Ca2+ Inducible Gene in Certain Triple-Negative Breast Cancer Cells

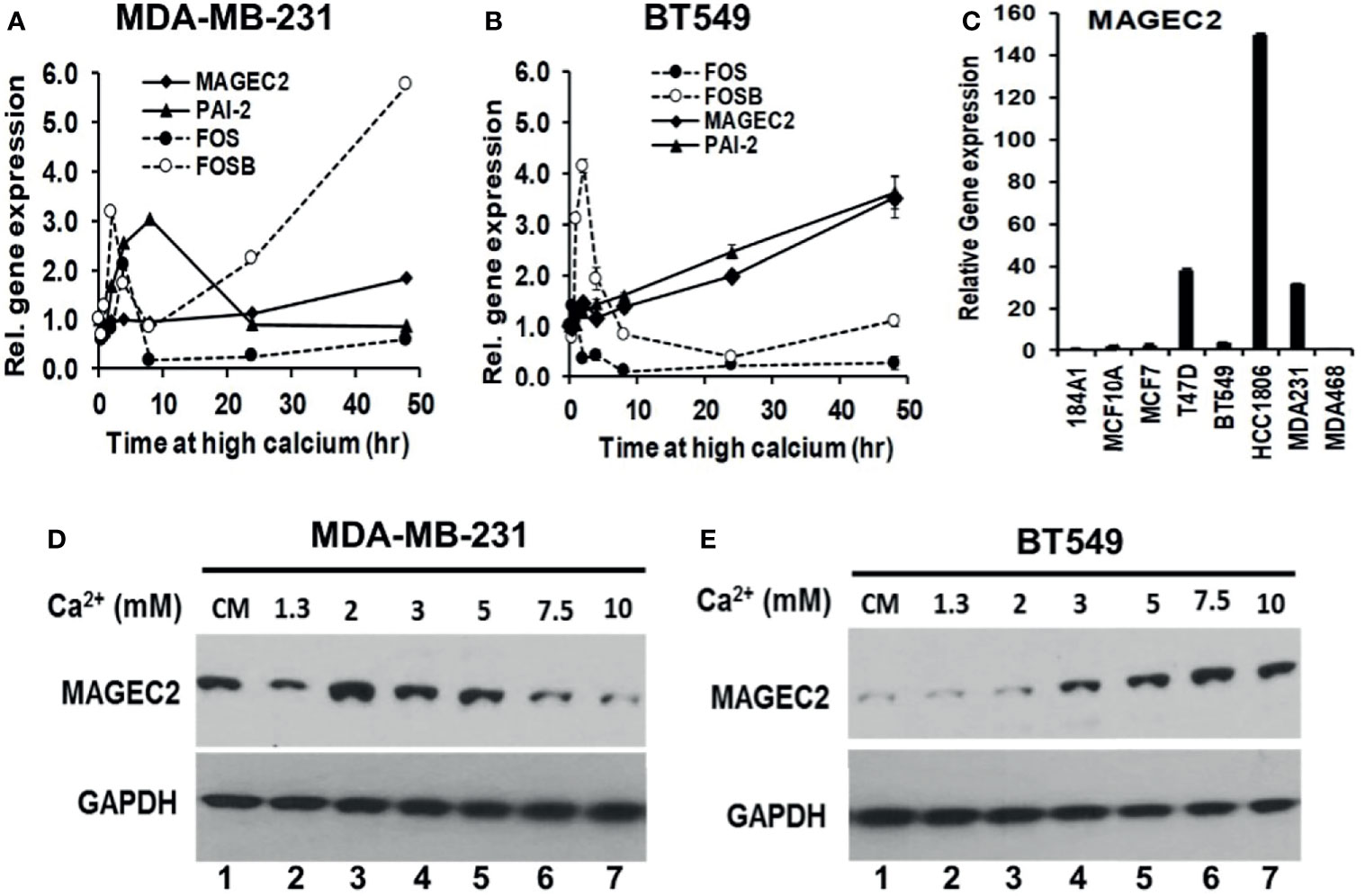

Based on the microarray data, we speculated that the expression of early response FOS and/or FOSB may lead to the expression of cancer progression associated genes such as MAGEC2. To test this, we first determined whether the expression of these early response genes occurred at distinct time periods compared to that of malignancy associated genes. BT-549 and MDA-MB-231 cells were cultured in complete medium (containing 1.3 mM Ca2+) or complete medium supplemented with 5.0 mM Ca2+ following a time course for up to 48 h. The high Ca2+-induced expression of these genes was verified by semi-quantitative RT-PCR using individual TaqMan assays (Table S1, Life Technologies). As shown in Figure 4A, up-regulation of the early response genes FOS/FOSB at high Ca2+ occurred within 2 h in MDA-MB-231 cells followed by a modest increase in the expression of MAGEC2 and PAI-2. In BT-549 cells, however, there was a robust increase in the expression of FOSB within 2 h, followed by a steady increase in the expression levels of MAGEC2 and PAI-2 (Figure 4B).

Figure 4 Induction of MAGEC2 expression by high extracellular calcium in TNBC cells. (A, B) Cells were cultured in complete medium with or without high Ca2+ (5.0 mM) for up to 48 h. Cells were harvested and total RNA extracted, and used for RT-PCR. Each point represents the expression of the indicated genes relative to GAPDH for MDA-MB-231 (A) and BT-549 (B) TNBC cells. (C) Total RNA was isolated from the indicated cell lines cultured in their respective complete media and the basal levels of MAGEC2 assessed by RT-PCR. (D, E) MDA-MB-231 (D) and BT-549 (E) TNBC cells were cultured in complete medium supplemented with the indicated concentrations of Ca2+, for 48 h. Cells were harvested and the expression of MAGEC2 protein was analyzed by western blotting.

To provide evidence for the difference in the response of MDA-MB-231 and BT-549 cells to high Ca2+ using MAGEC2 as the read out, we assessed the basal expression of MAGEC2 in these and other breast cell lines by RT-PCR. This analysis revealed that the basal expression of MAGEC2 in MDA-MB-231 cells was >10-fold that in BT-549 cells (Figure 4C). We next show that MDA-MB-231 cells indeed expressed higher levels of MAGEC2 at the protein level than BT-549 cells under basal culture conditions (Figures 4D, E, cf. lanes 1). Consistent with this difference in the basal expression of MAGEC2, we show that in MDA-MB-231 cells, the threshold for extracellular Ca2+ induced expression of MAGEC2 was ~2.0 mM and that higher concentrations of Ca2+ led to a consistent decrease in the expression of MAGEC2 (Figure 4D), and supports data in Figure 4A. On the other hand, treatment of BT-549 cells with various Ca2+ concentrations led to a consistent and Ca2+-dependent expression of MAGEC2 with a threshold at ~7.5 mM Ca2+ (Figure 4E), similar to data in Figure 4B. These data support the notion that distinct breast cancer cell lines not only have distinct thresholds but also varying potentials to adapt and to respond to the progressive increase in extracellular Ca2+.

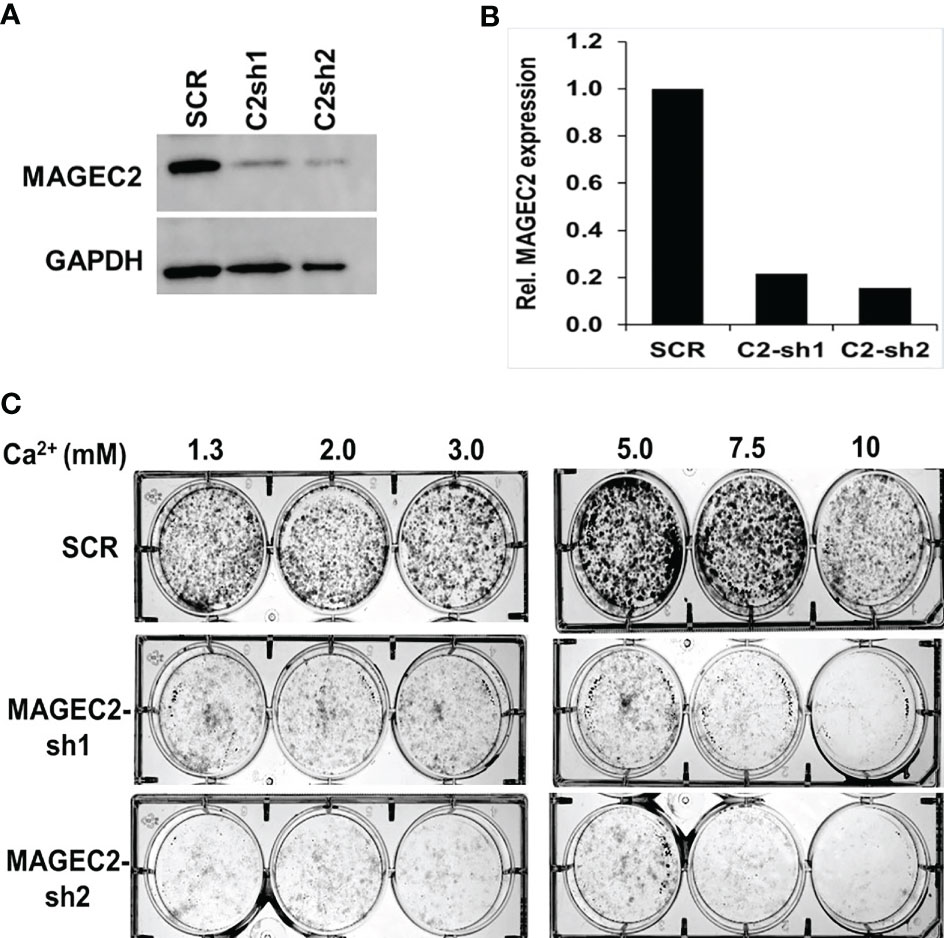

To confirm that the high Ca2+ inducible expression of MAGEC2 is required for cell growth, we transfected BT-549 cells with scramble control (SCR) or shRNAs targeting the coding sequence of MAGEC2 and verified the knockdowns by western blotting (Figure 5A). We then assessed the growth of the control (SCR) and two MAGEC2 shRNAs transfected cells at various concentrations of Ca2+ by clonogenic assays. Consistent with data in Figures 4B, E, we demonstrate that the growth of the control BT-549 cells was Ca2+ dependent with a threshold at ~7.5 mM Ca2+, while the growth of MAGEC2 shRNA transfected cells was inhibited and more so at Ca2+ concentrations >5.0 mM (Figure 5B).

Figure 5 Effect of MAGEC2 down regulation on the growth of TNBC cells in vitro. (A) BT-549 cells were transfected with control (SCR) or shRNA plasmids (MAGEC2-sh1 and MAGEC2-sh2) targeting MAGEC2. The expression of MAGEC2 was confirmed by western blotting. (B) The protein bands were quantified using the NIH ImageJ software. (C) Control and MAGEC2 down regulated cells were cultured in complete medium supplemented with the indicated concentrations of Ca2+ and cultured for up to 10 days. Cells were fixed and stained with crystal violet and the images were digitally captured.

Induction of MAGEC2 Expression by High Ca2+ Is Mediated via the AP-1 Transcription Factor

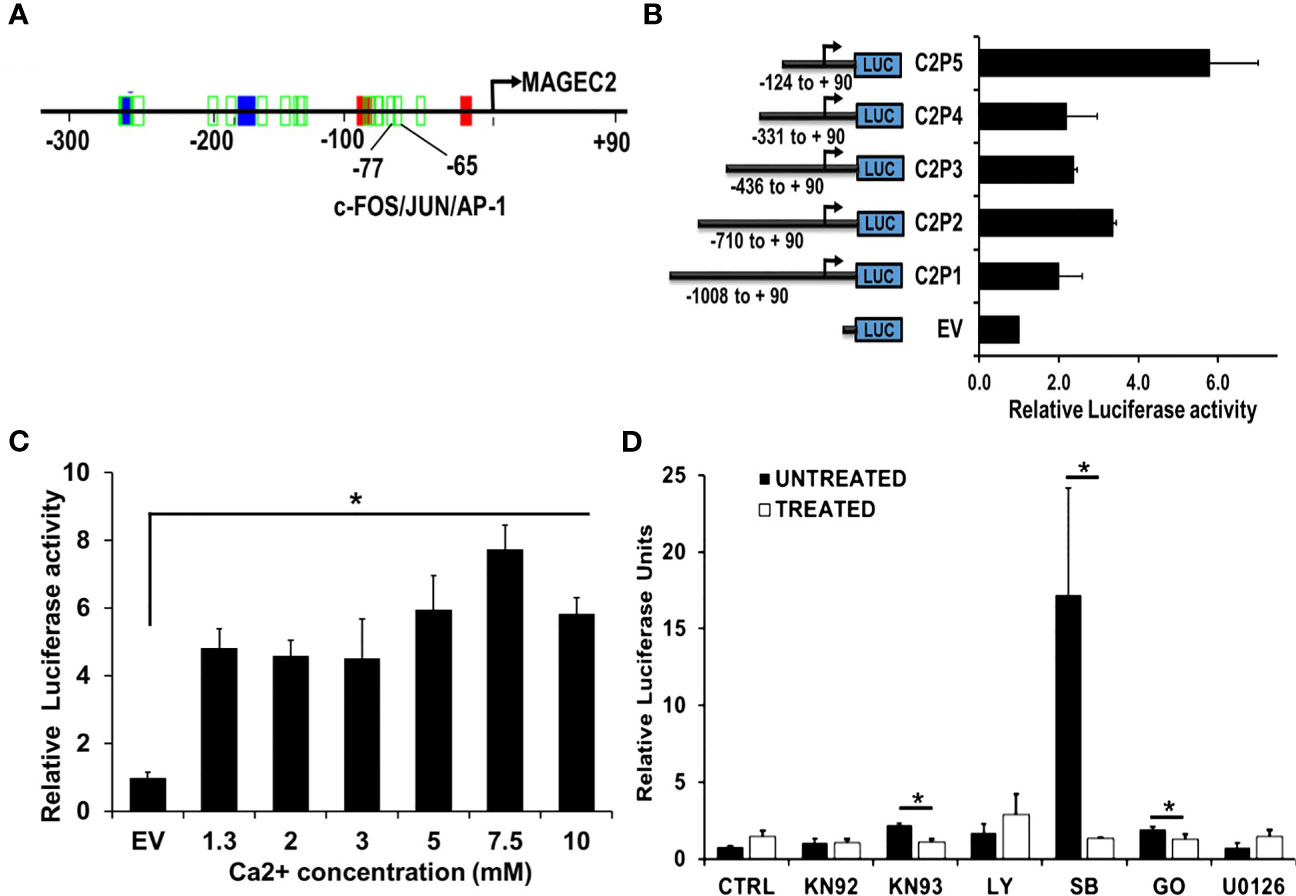

Given that the expression of FOS/FOSB early response genes at high Ca2+ peaked at ~2 h and steadily declined by ~8 hours (Figures 4A, B), we speculated that high Ca2+ induced expression of MAGEC2 may be mediated by these early response genes as components of the AP-1 transcription factor. To test this, we first show that the proximal promoter of MAGEC2 contains a bona fide AP-1/JUN/c-FOS binding site at -65 to -77 bp from the transcription start site (Figure 6A) based on the use of the Alggen prediction of transcription factor binding sites defined in the TRANSFAC database (Promo v3). To determine whether this promoter is responsive to high Ca2+, we carried out dual luciferase reporter assays using truncated versions of the MAGEC2 proximal promoter cloned upstream of firefly luciferase as depicted in Figure 6B. Analysis of luciferase expression revealed that the minimal proximal promoter denoted C2P5 (-124 to +90) containing the AP-1/JUN/c-FOS binding site was the most active at high Ca2+ (Figure 6B). We also show that the activity of the proximal promoter was Ca2+ concentration dependent with maximal activity at ~7.5 mM Ca2+ (Figure 6C) consistent with data in Figures 4, 5

Figure 6 The proximal MAGEC2 promoter is activated by high Ca+. (A) The AP-1 transcription factor binding site on the proximal promoter of MAGEC2 was identified by using the Promo V3 software. B) The proximal promoter fragments of MAGEC2 truncated as indicated were cloned into pGL4 basic, then used to transfect HEK293T cells. For luciferase activity, HEK293T cells transfected with the empty vector (EV) or the MAGEC2 truncated promoter fragments and Renilla luciferase expressing vector (for transfection control) were cultured in complete medium with or without high (5.0 mM) Ca2+. Luciferase expression at high Ca2+ was assessed relative to the control. (C) HEK293T cells transfected with C2P5 from (B) above were cultured in complete medium supplemented with the indicated concentrations of Ca2+ and the luciferase activity assessed as in (B) above. (D) HEK293 T cells transfected as in (B, C) above were cultured in complete medium and high Ca2+ with or without the indicated inhibitors. Luciferase activity was measured 48 h post treatment as in (B) above. Luciferase activity as normalized to the DMSO control. EV: empty vector; DMSO: Dimethylsufoxide vehicle control; UNT (untreated, drug free); KN92: inactive Ca2+/camodulin kinase inhibitor; KN93 active Ca2+/camodulin kinase inhibitor; LY: LY 294002, PI3 kinase inhibitor; SB: SB 203580 p38 MAP kinase inhibitor; GO: Gö 6976, Ca2+ dependent PKC inhibitor; U0126, MEK inhibitor. * denotes p < 0.05, ** denotes p < 0.01, *** denoted p < 0.0001. Statistical significance was determined by Student’s T-Test and two-way ANOVA, where (B, C) were quantified to have a statistical significance of </= 0.05.

It is well established that the activation of c-Fos and its translocation to the nucleus is stimulated by its phosphorylation (44–48). We speculated that certain Ca2+ activated protein kinases may be involved in driving the expression of MAGEC2 at high Ca2+. For this study, we used Ca2+/calmodulin kinase inhibitor (KN-93 and KN-92 as the respective control), p38 MAP kinase inhibitor (SB203580), a MEK1/2 inhibitor (U0126), a phosphatidylinositol 3-Kinase (PI3K)inhibitor (LY294002), and a conventional protein kinase C isoform inhibitor (Gö6983). To test this, we treated HEK293T cells transfected with the minimal proximal MAGEC2 promoter (C2P5) in medium supplemented with high Ca2+ with or without the indicated kinase inhibitors for 48 hours, and assessed the luciferase activity. This analysis revealed that inhibition of Ca2+/calmodulin kinase, p38 MAP kinase, and Ca2+-dependent protein kinase C isoform blocked the Ca2+ induced luciferase activity (Figure 6D). This suggests that these kinases are, in part, responsible for the activation and subsequent transcriptional activity of c-FOS at high Ca2+.

High Ca2+ Inducible Expression of MAGEC2 Is Mediated by c-FOS/AP-1 Transcription Factor

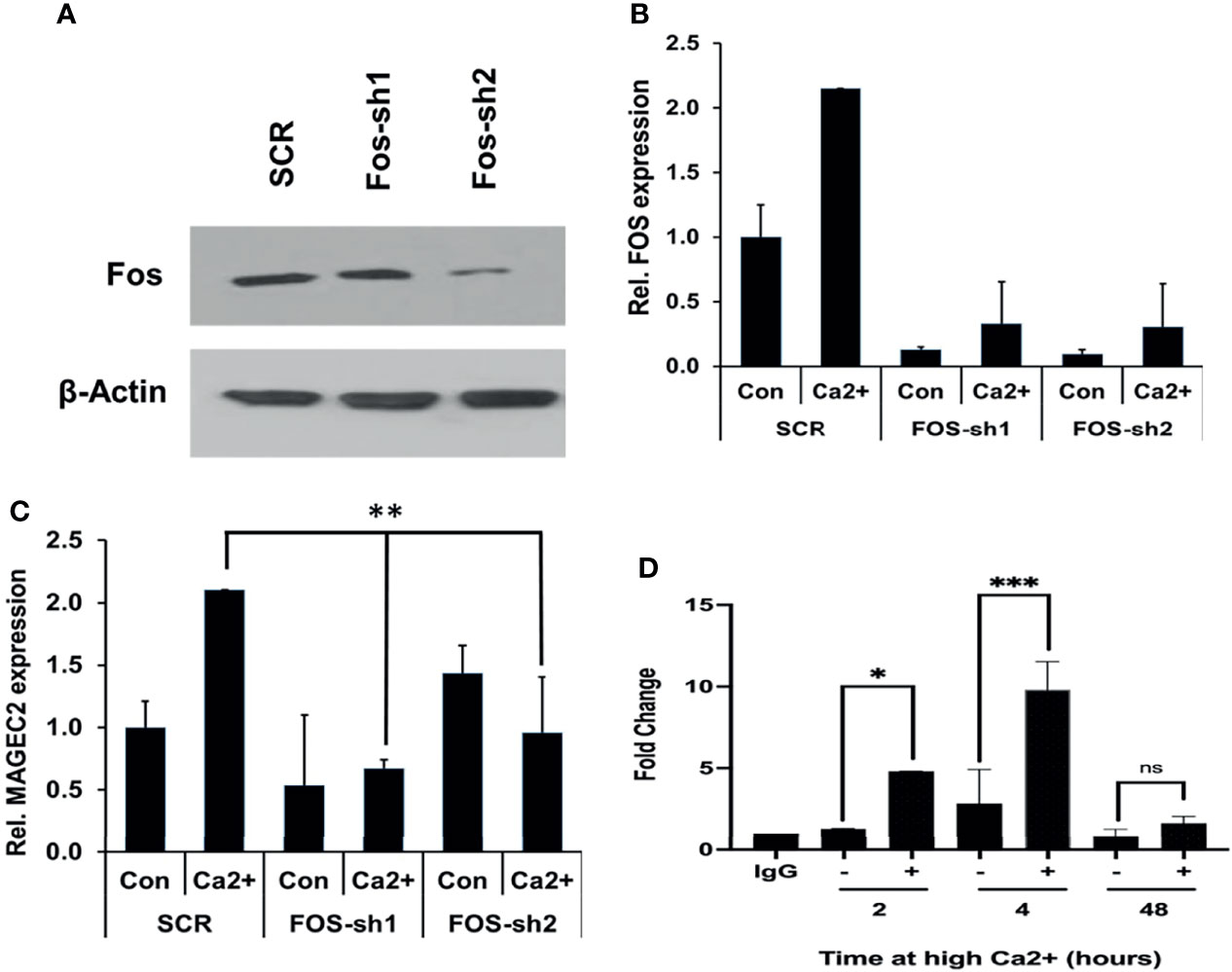

As critical components of the AP-1 transcription factor, c-FOS and its homolog FOSB detected in our microarray data may contribute to the expression of MAGEC2. We first assessed whether downregulation of either FOS or FOSB could affect the transcription of MAGEC2 at high Ca2+. Here, we show that downregulation of c-FOS protein (Figure 7A) or mRNA (Figure 7B) in BT-549 cells was associated with a significant decrease in the transcription of MAGEC2 at high Ca2+ (Figure 7C).

Figure 7 High Ca2+-induced expression of MAGEC2 is attenuated following downregulation of cFOS. (A) BT-549 cells were transfected with control (SCR) or shRNA plasmids (FOS-sh1 and FOS-sh2) targeting c-FOS. The expression of c-FOS was confirmed by western blotting. (B, C) BT-549 cells transfected with control or c-FOS targeting shRNAs were cultured in complete medium without (Con) or with high Ca2+ (Ca2+) for 48 h. The cells were harvested and the expression of c-FOS (C) and MAGEC2 (D) assessed by RT-PCR. (D) Parental BT-549 cells were grown to 70-80% confluency, then treated with or without high Ca2+ for the indicated times. Cells were subsequently cross-linked and processed for ChIP assays as described in materials and methods using antibodies against c-FOS. Purified DNA fragments were analyzed by real-time PCR and presented as fold change relative to IgG control. Con, complete medium control; Ca2+, complete medium supplemented with high Ca2+. * denotes p < 0.05, ** denotes p < 0.001, *** denotes p < 0.0001, ns denotes not significant.

Finally, we tested whether c-Fos bound to the promoter of MAGEC2 by chromatin immunoprecipitation. In this assay, antibodies to c-Fos were used for the immunoprecipitation, and primers for the minimal proximal promoter (C2P5) were used to amplify the recovered DNA fragments from BT-549 cells cultured in complete medium supplemented with high Ca2+ for 2, 4, and 48 hours. This analysis revealed that high Ca2+ enhanced the binding of c-Fos to the MAGEC2 promoter in a time dependent manner with maximal binding at ~4 h (Figure 7D). Together, these data suggest that MAGEC2 is a Ca2+-inducible gene in TNBC cells and that the aberrant expression of this gene in malignant tissues is at least in part, mediated via c-Fos and the AP-1 transcription factor.

Discussion

Dysregulation of systemic Ca2+ homeostasis, especially in patients with high-grade tumors, is common, due to increased secretion of PTHrP and the development of co-morbidities such as cancer-induced hypercalcemia (CIH) (7, 49–53). High extracellular Ca2+ is known to promote the growth and motility of breast cancer cells via the CaSR (54–56), but the mechanisms remain not only complicated, but also poorly understood. This is especially true for the molecularly heterogeneous breast cancer in which circulating Ca2+ is associated with larger and aggressive tumors in post-menopausal women and pre-menopausal women, respectively (9, 10). In this study, we sought to determine the effect of sustained high Ca2+ on the growth and motility of TNBC cells and to delineate the mechanism underlying the increase in cell growth and motility at high extracellular Ca2+. We show that sustained high extracellular Ca2+ decreased the sensitivity of CaSR to Ca2+ but rather stimulated tumor cell growth and migration. Our data also reveal that the expression levels, mutational status in exon 7 of the CASR as well as the Ca2+ influx dynamics do not completely explain the distinct responses of breast epithelial and breast cancer cell lines to an increase in extracellular Ca2+. However, high extracellular Ca2+ provokes the expression of early response genes that in turn lead to the expression of malignancy associated genes that presumably drive the growth and motility of the tumor cells. The identification of MAGEC2 as a Ca2+ inducible gene supports this novel paradigm in Ca2+sensing and signaling in TNBC cells. Overall, this study suggests for the first time that the aberrant expression of MAGEC2 that is frequently observed in malignant solid tumors may at least in part be mediated by a cancer-induced increase in circulating Ca2+.

Although the CaSR plays a critical role in systemic Ca2+ homeostasis and promotes tumor cell growth and migration (54–56), the underlying mechanisms remain poorly understood. Previously, our lab showed that expression of CASR variants at rs1801725 is associated with a higher risk of developing secondary neoplastic lesions in the lungs and bone (19). We genotyped several breast cancer cell lines to determine if they have the wild-type CASR or the mutated CASR (Table 1). We show that, along with the heterogeneity among breast cancer cell lines, there are also differences among the cell lines as to how the cells respond to high Ca2+ in vitro. As predominantly inactivating mutations, CASR variants at rs1801725 and rs1801726 may contribute to the desensitization of the receptor to Ca2+ (57–61) and as such, may shift the response of tumor cells to higher set points of Ca2+. This reduced sensitivity of the CaSR may not only blunt the response of tumor cells to circulating Ca2+ but also facilitate the growth and motility of tumor cell via cytosolic Ca2+ mediated processes. Interestingly, previous studies reported that expression of the wild type and the activating R990G CaSR mutant in exon 7 of the receptor were both necessary and sufficient to induce humoral hypercalcemia of malignancy in lung squamous cell carcinoma xenograft tumor bearing mice (62). However, whether the expression of exon 7 inactivating CASR mutants in TNBC cells also influence the development of hypercalcemia remains to be fully elucidated.

In the tumor microenvironment and especially at metastatic sites, Ca2+ is a predominant but one of the least studied factors in TNBC biology. Although it is well established that circulating Ca2+ is associated with cancer progression (9, 10), the effects of high Ca2+ on tumor growth varies from one cancer type to another (54, 63, 64). For instance, high extracellular Ca2+ inhibits the proliferation of colon cancer and parathyroid cells (54, 65) but stimulates both the proliferation and metastatic potentials of breast and prostate cancer cells (55). Our study reveals that for the same cancer type, the response of various cancer cells to high Ca2+ is cell type specific. Whether this depends on the expression level and/or the expression of activating or inactivating mutant CaSRs by the cells is still poorly understood. This is further complicated by the diverse and often cell type dependent Ca2+ entry mechanisms (65, 66), the several Ca2+ dependent factors (15, 67, 68), signaling pathways (11, 13, 17, 69, 70) and a plethora of cellular functions modulated by an increase in cytosolic Ca2+ (69, 70). This notwithstanding, as cancer progresses to the more malignant stages, patients inevitably develop cancer-induced hypercalcemia (49–52) which may invariably influence the progression of the disease via the CaSR or independent of CaSR.

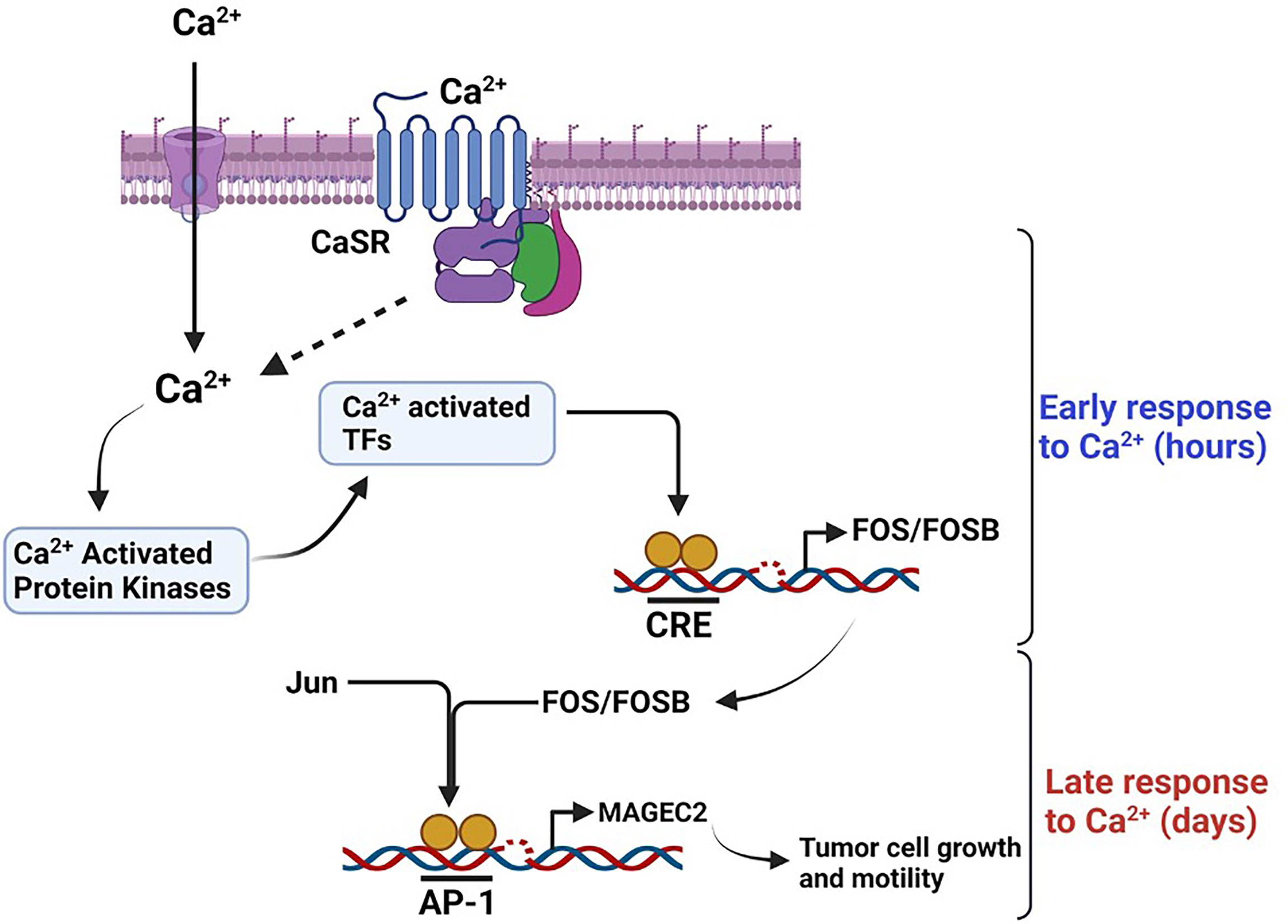

Based on data from this study, it is possible that the outcome of breast cancer may be dictated by the response of tumor cells to progressive increase in Ca2+ as the disease progresses. Our data suggest that high Ca2+ adapted cells may develop into larger more aggressive tumors (9, 10), while Ca2+-sensitive tumor cells may develop into slow growing, less aggressive tumors. As illustrated in Figure 8, we propose the novel paradigm that an increase in cytosolic Ca2+ activates Ca2+ responsive protein kinases that activate Ca2+ responsive transcription factors (71, 72) and that in turn lead to the expression of early response genes (ERGs) such as c-FOS (15, 44–46, 73, 74). Dimerization of c-Fos with Jun proteins to form active AP-1 transcription factors (44, 47, 74), potentially drives the high Ca2+ inducible expression of malignancy-associated genes such as MAGEC2. Based on this model, it is possible that high extracellular Ca2+ exerts a selection pressure to enable tumor cells to either become less sensitive to Ca2+ but more aggressive or more sensitive to Ca2+ and less aggressive. This is supported by previous studies showing that high circulating Ca2+ is associated with aggressive tumors in premenopausal women and larger tumors in post-menopausal women (9, 10). Consistent with this notion, it is also possible that TNBC cells with the propensity to spread to Ca2+-rich skeletal sites may be those that become insensitive to high Ca2+ or are high Ca2+ adapted following a priming stage dictated by a progressive increase in circulating Ca2+ as the disease progresses. It is possible that the survival of Ca2+ adapted cells may be sustained by high Ca2+ inducible expression of genes that influence tumor cell growth and/or motility such as MAGEC2.

Figure 8 Schematic diagram depicting the effect of high Ca2+ on the expression of MAGEC2 in TNBC cells. High extracellular Ca2+ acting via the CaSR provokes store operated Ca2+ entry, the subsequent surge in intracellular Ca2+activates Ca2+ activated kinase such as conventional PKC isoforms which in turn activate immediate early Ca2+ activated transcription factors such as CREB/ATF4. These transcription factors lead to the expression of early response genes such as c-FOS which upon dimerization with Jun proteins bind to the AP-1 site on target genes such as MAGEC2 and provoke their transcription. Up regulation of MAGEC2 may then facilitate the adaptation of the cells to high Ca2+ and enhance their growth and metastatic properties.

Up regulation of MAGEC2 and other high Ca2+ inducible genes that influence the growth and motility of tumor cells may be invaluable in the adaptation of tumor cells to high Ca2+ as depletion of this gene strongly attenuated the growth of the cells in either normal or high Ca2+ conditions. High Ca2+ and especially if sustained for a relatively long period may be stressful to cells that are not adapted to higher than normal circulating levels. Without adaptive mechanisms, including modulation of various Ca2+ channel activity, sustained high Ca2+may trigger cell death or senescence (74, 75). Our data suggest that the initial response to high Ca2+ is the expression of early response genes which is subsequently translated into the expression of genes that enable the tumor cells to strive under the sustained high Ca2+ conditions. This is the case of MAGEC2, a cancer-testis antigen that is known to be aberrantly expressed in highly malignant breast and other neoplasms (75). Even though MAGEC2 is now known to play an important role in tumor progression, our study suggests that the up regulation of this gene in malignant TNBC is triggered by high extracellular Ca2+ and presumably, breast cancer-induced hypercalcemia in patients with advanced and metastasis-prone disease stages. This is supported by our TCGA data analysis showing an increase in the expression of MAGEC2 in invasive ductal carcinomas compared to normal breast tissues. Although this study established a link between high Ca2+ and the expression of MAGEC2, it remains unclear whether the pathway to high Ca2+ adaptation inevitably requires extracellular Ca2+ sensing/signaling via the CaSR and/or Ca2+ entry mechanisms including Ca2+ activated nonselective cation channels (36). Further studies will be necessary to determine the fate of high Ca2+-adapted TNBCs in vitro and in vivo, and whether high Ca2+ inducible expression of malignancy-associated genes is reversible following treatment with Ca2+ lowering drugs. Further studies are also warranted to validate MAGEC2 and other high Ca2+-inducible genes as biomarkers for hypercalcemia modulated cancer progression and metastasis.

Conclusion

Data from this study suggests for the first time that the aberrant expression of MAGEC2 and presumably related cancer-testis antigens in malignant solid tumors is triggered at least in part by high circulating Ca2+. This study also provides novel mechanistic insights into the hitherto unappreciated oncogenic effects of high extracellular Ca2+, especially in advanced breast cancers.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are publicly available. This data can be found here: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/, GSE189520.

Author Contributions

This work was conceptualized by AS. The methodology, data generation and analysis was conducted by HB, SP, SEW, SDW, OK, CN, DW, and AS. Initial writing, editing and reviewing of the manuscript was conducted by HB and AS and the final review of the manuscript and editing was conducted by HB, SEW, DW, SDW, OK, CN, JO, and AS. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the NIH/NIGMS 5SC2 CA170244 and SC1 CA211030 (to AS), 8U54 MD007593, Meharry Translational Research Center (MeTRC) and P50CA098131 (Vanderbilt-Ingram Cancer Center SPORE in Breast Cancer). This study used resources from the Meharry RCMI Infrastructure Core (CRISALIS) which is supported by U54 MD007586. HB was supported by U54 CA163069; SEW, DW, and SDW were supported by R25 GM059994; and CN was supported by the Federal Work Study (FWS) program. The content of this manuscript is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Dr. Aramandla Ramesh of Meharry Medical College for his insight and feedback regarding the manuscript. The schematic summary was created using BioRender.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fendo.2022.816598/full#supplementary-material

References

1. Carey LA, Perou CM, Livasy CA, Dressler LG, Cowan D, Conway K, et al. Race, Breast Cancer Subtypes, and Survival in the Carolina Breast Cancer Study. JAMA (2006) 295:2492. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.21.2492

2. Siddharth S, Sharma D. Racial Disparity and Triple-Negative Breast Cancer in African-American Women: A Multifaceted Affair Between Obesity, Biology, and Socioeconomic Determinants. Cancers (2018) 10:514. doi: 10.3390/cancers10120514

3. Coleman RE. Metastatic Bone Disease: Clinical Features, Pathophysiology and Treatment Strategies. Cancer Treat Rev (2001) 27:165–76. doi: 10.1053/ctrv.2000.0210

4. Coleman RE. Clinical Features of Metastatic Bone Disease and Risk of Skeletal Morbidity. Clin Cancer Res (2006) 12:6243s–9s. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-0931

5. Coleman R, Rubens R. The Clinical Course of Bone Metastases From Breast Cancer. Br J Cancer (1987) 55:61–6. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1987.13

6. Chirgwin JM, Guise TA. Molecular Mechanisms of Tumor-Bone Interactions in Osteolytic Metastases. Crit Rev Eukaryot Gene Expr (2000) 10:159–78. doi: 10.1615/CritRevEukarGeneExpr.v10.i2.50

7. DeMauro S, Wysolmerski J. Hypercalcemia in Breast Cancer: An Echo of Bone Mobilization During Lactation? J Mammary Gland Biol Neoplasia (2005) 10:157–67. doi: 10.1007/s10911-005-5398-9

8. Guise TA, Kozlow WM, Heras-Herzig A, Padalecki SS, Yin JJ, Chirgwin JM. Molecular Mechanisms of Breast Cancer Metastases to Bone. Clin Breast Cancer (2005) 5:S46–53. doi: 10.3816/CBC.2005.s.004

9. Almquist M, Anagnostaki L, Bondeson L, Bondeson A-G, Borgquist S, Landberg G, et al. Serum Calcium and Tumour Aggressiveness in Breast Cancer: A Prospective Study of 7847 Women. Eur J Cancer Prev (2009) 18:354–60. doi: 10.1097/CEJ.0b013e32832c386f

10. Thaw SSH, Sahmoun A, Schwartz GG. Serum Calcium, Tumor Size, and Hormone Receptor Status in Women With Untreated Breast Cancer. Cancer Biol Ther (2012) 13:467–71. doi: 10.4161/cbt.19606

11. Bagur R, Hajnóczky G. Intracellular Ca 2+ Sensing: Its Role in Calcium Homeostasis and Signaling. Mol Cell (2017) 66:780–8. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2017.05.028

12. Hannan FM, Kallay E, Chang W, Brandi ML, Thakker RV. The Calcium-Sensing Receptor in Physiology and in Calcitropic and Noncalcitropic Diseases. Nat Rev Endocrinol (2018) 15:33–51. doi: 10.1038/s41574-018-0115-0

13. Roberts-Thomson SJ, Chalmers SB, Monteith GR. The Calcium-Signaling Toolkit in Cancer: Remodeling and Targeting. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol (2019) 11:a035204. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a035204

14. Sanders JL, Chattopadhyay N, Kifor O, Yamaguchi T, Butters RR, Brown EM. Extracellular Calcium-Sensing Receptor Expression and Its Potential Role in Regulating Parathyroid Hormone-Related Peptide Secretion in Human Breast Cancer Cell Lines. Endocrinology (2000) 141:4357–64. doi: 10.1210/endo.141.12.7849

15. Coulon V, Veyrune J-L, Tourkine N, Vié A, Hipskind RA. Blanchard J-M. A Novel Calcium Signaling Pathway Targets the C-Fosintragenic Transcriptional Pausing Site. J Biol Chem (1999) 274:30439–46. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.43.30439

16. Brown EM, Gamba G, Riccardi D, Lombardi M, Butters R, Kifor O, et al. Cloning and Characterization of an Extracellular Ca(2+)-Sensing Receptor From Bovine Parathyroid. Nature (1993) 366:575–80. doi: 10.1038/366575a0

17. Brown EM, MacLeod RJ. Extracellular Calcium Sensing and Extracellular Calcium Signaling. Physiol Rev (2001) 81:239–97. doi: 10.1152/physrev.2001.81.1.239

18. Wang L, Widatalla SE, Whalen DS, Ochieng J, Sakwe AM. Association of Calcium Sensing Receptor Polymorphisms at Rs1801725 With Circulating Calcium in Breast Cancer Patients. BMC Cancer (2017) 17:511. doi: 10.1186/s12885-017-3502-3

19. Actkins KV, Beasley HK, Faucon AB, Davis LK, Sakwe AM. Calcium-Sensing Receptor Polymorphisms at Rs1801725 Are Associated With Increased Risk of Secondary Malignancies. Oncology (2021). doi: 10.1101/2021.02.24.21252297

20. Coulie PG, Van den Eynde BJ, van der Bruggen P, Boon T. Tumour Antigens Recognized by T Lymphocytes: At the Core of Cancer Immunotherapy. Nat Rev Cancer (2014) 14:135–46. doi: 10.1038/nrc3670

21. Chen X, Wang L, Liu J, Huang L, Yang L, Gao Q, et al. Expression and Prognostic Relevance of MAGE-A3 and MAGE-C2 in Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer. Oncol Lett (2017) 13:1609–18. doi: 10.3892/ol.2017.5665

22. von Boehmer L, Keller L, Mortezavi A, Provenzano M, Sais G, Hermanns T, et al. MAGE-C2/CT10 Protein Expression Is an Independent Predictor of Recurrence in Prostate Cancer. PloS One (2011) 6:e21366. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0021366

23. Yang F, Zhou X, Miao X, Zhang T, Hang X, Tie R, et al. MAGEC2, an Epithelial-Mesenchymal Transition Inducer, Is Associated With Breast Cancer Metastasis. Breast Cancer Res Treat (2014) 145:23–32. doi: 10.1007/s10549-014-2915-9

24. Wang J, Song X, Guo C, Wang Y, Yin Y. Establishment of MAGEC 2-Knockout Cells and Functional Investigation of MAGEC 2 in Tumor Cells. Cancer Sci (2016) 107:1888–97. doi: 10.1111/cas.13082

25. Hou S, Sang M, Zhao L, Hou R, Shan B. The Expression of MAGE-C1 and MAGE-C2 in Breast Cancer and Their Clinical Significance. Am J Surg (2016) 211:142–51. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2015.05.028

26. Doyle JM, Gao J, Wang J, Yang M, Potts PR. MAGE-RING Protein Complexes Comprise a Family of E3 Ubiquitin Ligases. Mol Cell (2010) 39:963–74. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.08.029

27. Song X, Hao J, Wang J, Guo C, Wang Y, He Q, et al. The Cancer/Testis Antigen MAGEC2 Promotes Amoeboid Invasion of Tumor Cells by Enhancing STAT3 Signaling. Oncogene (2017) 36:1476–86. doi: 10.1038/onc.2016.314

28. Koumangoye RB, Nangami GN, Thompson PD, Agboto VK, Ochieng J, Sakwe AM. Reduced Annexin A6 Expression Promotes the Degradation of Activated Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor and Sensitizes Invasive Breast Cancer Cells to EGFR-Targeted Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitors. Mol Cancer (2013) 12:167. doi: 10.1186/1476-4598-12-167

29. Sakwe AM, Koumangoye R, Guillory B, Ochieng J. Annexin A6 Contributes to the Invasiveness of Breast Carcinoma Cells by Influencing the Organization and Localization of Functional Focal Adhesions. Exp Cell Res (2011) 317:823–37. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2010.12.008

30. Cheng I. Identification and Localization of the Extracellular Calcium-Sensing Receptor in Human Breast. J Clin Endocrinol Metab (1998) 83:703–7. doi: 10.1210/jc.83.2.703

31. Vanhouten JN, Wysolmerski JJ. The Calcium-Sensing Receptor in the Breast. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab (2013) 27:403–14. doi: 10.1016/j.beem.2013.02.011

32. Pratt JH, Ambrosius WT, Wagner MA, Maharry K. Molecular Variations in the Calcium-Sensing Receptor in Relation to Sodium Balance and Presence of Hypertension in Blacks and Whites. Am J Hypertens (2000) 13:654–8. doi: 10.1016/s0895-7061(99)00285-x

33. Bai M, Trivedi S, Brown EM. Dimerization of the Extracellular Calcium-Sensing Receptor (CaR) on the Cell Surface of CaR-Transfected HEK293 Cells. J Biol Chem (1998) 273:23605–10. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.36.23605

34. Cole DE, Peltekova VD, Rubin LA, Hawker GA, Vieth R, Liew CC, et al. A986S Polymorphism of the Calcium-Sensing Receptor and Circulating Calcium Concentrations. Lancet (1999) 353:112–5. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(98)06434-4

35. Sakwe AM, Larsson M, Rask L. Involvement of Protein Kinase C-Alpha and -Epsilon in Extracellular Ca2 Signalling Mediated by the Calcium Sensing Receptor. Exp Cell Res (2004) 297:560–73. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2004.03.039

36. Hiani YE, Ahidouch A, Roudbaraki M, Guenin S, Brûlé G, Ouadid-Ahidouch H. Calcium-Sensing Receptor Stimulation Induces Nonselective Cation Channel Activation in Breast Cancer Cells. J Membrane Biol (2006) 211:127–37. doi: 10.1007/s00232-006-0017-2

37. Roderick HL, Cook SJ. Ca2+ Signalling Checkpoints in Cancer: Remodelling Ca2+ for Cancer Cell Proliferation and Survival. Nat Rev Cancer (2008) 8:361–75. doi: 10.1038/nrc2374

38. Gelder MEM, Look MP, Peters HA, Schmitt M, Brünner N, Harbeck N, et al. Urokinase-Type Plasminogen Activator System in Breast Cancer: Association With Tamoxifen Therapy in Recurrent Disease. Cancer Res (2004) 64:4563–8. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-03-3848

39. Spyratos F, Bouchet C, Tozlu S, Labroquere M, Vignaud S, Becette V, et al. Prognostic Value of uPA, PAI-1 and PAI-2 mRNA Expression in Primary Breast Cancer. Anticancer Res (2002) 22:2997–3003.

40. Ma W, Vigneron N, Chapiro J, Stroobant V, Germeau C, Boon T, et al. Van Den Eynde BJ. A MAGE-C2 Antigenic Peptide Processed by the Immunoproteasome Is Recognized by Cytolytic T Cells Isolated From a Melanoma Patient After Successful Immunotherapy. Int J Cancer (2011) 129:2427–34. doi: 10.1002/ijc.25911

41. Chida K, Nagamori S, Kuroki T. Nuclear Translocation of Fos Is Stimulated by Interaction With Jun Through the Leucine Zipper. CMLS Cell Mol Life Sci (1999) 55:297–302. doi: 10.1007/s000180050291

42. Malnou CE, Brockly F, Favard C, Moquet-Torcy G, Piechaczyk M, Jariel-Encontre I. Heterodimerization With Different Jun Proteins Controls C-Fos Intranuclear Dynamics and Distribution. J Biol Chem (2010) 285:6552–62. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.032680

43. Sasaki T, Kojima H, Kishimoto R, Ikeda A, Kunimoto H, Nakajima K. Spatiotemporal Regulation of C-Fos by ERK5 and the E3 Ubiquitin Ligase UBR1, and Its Biological Role. Mol Cell (2006) 24:63–75. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.08.005

44. Vesely PW, Staber PB, Hoefler G, Kenner L. Translational Regulation Mechanisms of AP-1 Proteins. Mutat Research/Reviews Mutat Res (2009) 682:7–12. doi: 10.1016/j.mrrev.2009.01.001

45. Adler J, Reuven N, Kahana C, Shaul Y. C-Fos Proteasomal Degradation Is Activated by a Default Mechanism, and Its Regulation by NAD(P)H:Quinone Oxidoreductase 1 Determines C-Fos Serum Response Kinetics. Mol Cell Biol (2010) 30:3767–78. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00899-09

46. Lumachi F, Brunello A, Roma A, Basso U. Cancer-Induced Hypercalcemia. Anticancer Res (2009) 29:1551–5.

47. Grill V. Hypercalcemia of Malignacy. Rev Endocrine Metab Disord (2000) 1:253–63. doi: 10.1023/A:1026597816193

48. Goldner W. Cancer-Related Hypercalcemia. J Oncol Pract (2016) 12:426–32. doi: 10.1200/JOP.2016.011155

49. Stewart AF. Hypercalcemia Associated With Cancer. N Engl J Med (2005) 352:373–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcp042806

50. Cooper Worobey C, Magee CC. Humoral Hypercalcemia of Malignancy Presenting After Oncologic Surgery. Kidney Int (2006) 70:225–9. doi: 10.1038/sj.ki.5000401

51. Tennakoon S, Aggarwal A, Kállay E. The Calcium-Sensing Receptor and the Hallmarks of Cancer. Biochim Biophys Acta (2016) 1863:1398–407. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2015.11.017

52. Saidak Z, Boudot C, Abdoune R, Petit L, Brazier M, Mentaverri R, et al. Extracellular Calcium Promotes the Migration of Breast Cancer Cells Through the Activation of the Calcium Sensing Receptor. Exp Cell Res (2009) 315:2072–80. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2009.03.003

53. Das S, Clézardin P, Kamel S, Brazier M, Mentaverri R. The CaSR in Pathogenesis of Breast Cancer: A New Target for Early Stage Bone Metastases. Front Oncol (2020) 10:69. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2020.00069

54. Guarnieri V, Canaff L, Yun FHJ, Scillitani A, Battista C, Muscarella LA, et al. Calcium-Sensing Receptor (CASR) Mutations in Hypercalcemic States: Studies From a Single Endocrine Clinic Over Three Years. J Clin Endocrinol Metab (2010) 95:1819–29. doi: 10.1210/jc.2008-2430

55. Hendy GN, D’Souza-Li L, Yang B, Canaff L, Cole DE. Mutations of the Calcium-Sensing Receptor (CASR) in Familial Hypocalciuric Hypercalcemia, Neonatal Severe Hyperparathyroidism, and Autosomal Dominant Hypocalcemia. Hum Mutat (2000) 16:281–96. doi: 10.1002/1098-1004(200010)16:4<281::AID-HUMU1>3.0.CO;2-A

56. Yun FHJ, Wong BYL, Chase M, Shuen AY, Canaff L, Thongthai K, et al. Genetic Variation at the Calcium-Sensing Receptor (CASR) Locus: Implications for Clinical Molecular Diagnostics. Clin Biochem (2007) 40:551–61. doi: 10.1016/j.clinbiochem.2006.12.011

57. Pidasheva S, D’Souza-Li L, Canaff L, Cole DEC, Hendy GN. CASRdb: Calcium-Sensing Receptor Locus-Specific Database for Mutations Causing Familial (Benign) Hypocalciuric Hypercalcemia, Neonatal Severe Hyperparathyroidism, and Autosomal Dominant Hypocalcemia. Hum Mutat (2004) 24:107–11. doi: 10.1002/humu.20067

58. Bai M, Quinn S, Trivedi S, Kifor O, Pearce SHS, Pollak MR, et al. Expression and Characterization of Inactivating and Activating Mutations in the Human Ca2+-Sensing Receptor. J Biol Chem (1996) 271:19537–45. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.32.19537

59. Lorch G, Viatchenko-Karpinski S, Ho H-T, Dirksen WP, Toribio RE, Foley J, et al. The Calcium-Sensing Receptor Is Necessary for the Rapid Development of Hypercalcemia in Human Lung Squamous Cell Carcinoma. Neoplasia (2011) 13:428–38. doi: 10.1593/neo.101620

60. Hernández-Bedolla MA, Carretero-Ortega J, Valadez-Sánchez M, Vázquez-Prado J, Reyes-Cruz G. Chemotactic and Proangiogenic Role of Calcium Sensing Receptor Is Linked to Secretion of Multiple Cytokines and Growth Factors in Breast Cancer MDA-MB-231 Cells. Biochim Biophys Acta (BBA) - Mol Cell Res (2015) 1853:166–82. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2014.10.011

61. Liu G, Hu X, Chakrabarty S. Calcium Sensing Receptor Down-Regulates Malignant Cell Behavior and Promotes Chemosensitivity in Human Breast Cancer Cells. Cell Calcium (2009) 45:216–25. doi: 10.1016/j.ceca.2008.10.004

62. Aggarwal A, Prinz-Wohlgenannt M, Gröschel C, Tennakoon S, Meshcheryakova A, Chang W, et al. The Calcium-Sensing Receptor Suppresses Epithelial-to-Mesenchymal Transition and Stem Cell- Like Phenotype in the Colon. Mol Cancer (2015) 14:61. doi: 10.1186/s12943-015-0330-4

63. Duffy MJ, Duggan C. The Urokinase Plasminogen Activator System: A Rich Source of Tumour Markers for the Individualised Management of Patients With Cancer. Clin Biochem (2004) 37:541–8. doi: 10.1016/j.clinbiochem.2004.05.013

64. Lee D, Hong JH. Ca2+ Signaling as the Untact Mode During Signaling in Metastatic Breast Cancer. Cancers (2021) 13:1473. doi: 10.3390/cancers13061473

65. Motiani RK, Abdullaev IF. Trebak M. A Novel Native Store-Operated Calcium Channel Encoded by Orai3. J Biol Chem (2010) 285:19173–83. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.102582

66. Dewenter M, von der Lieth A, Katus HA, Backs J. Calcium Signaling and Transcriptional Regulation in Cardiomyocytes. Circ Res (2017) 121:1000–20. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.117.310355

67. West AE, Chen WG, Dalva MB, Dolmetsch RE, Kornhauser JM, Shaywitz AJ, et al. Calcium Regulation of Neuronal Gene Expression. Proc Natl Acad Sci (2001) 98:11024–31. doi: 10.1073/pnas.191352298

68. Berridge MJ, Lipp P, Bootman MD. The Versatility and Universality of Calcium Signalling. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol (2000) 1:11–21. doi: 10.1038/35036035

69. Bootman MD. Calcium Signaling. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol (2012) 4:a011171. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a011171

70. Greer PL, Greenberg ME. From Synapse to Nucleus: Calcium-Dependent Gene Transcription in the Control of Synapse Development and Function. Neuron (2008) 59:846–60. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.09.002

71. Hogan PG. Transcriptional Regulation by Calcium, Calcineurin, and NFAT. Genes Dev (2003) 17:2205–32. doi: 10.1101/gad.1102703

72. Gandolfi D, Cerri S, Mapelli J, Polimeni M, Tritto S, Fuzzati-Armentero M-T, et al. Activation of the CREB/c-Fos Pathway During Long-Term Synaptic Plasticity in the Cerebellum Granular Layer. Front Cell Neurosci (2017) 11:184. doi: 10.3389/fncel.2017.00184

73. Farfariello V, Iamshanova O, Germain E, Fliniaux I, Prevarskaya N. Calcium Homeostasis in Cancer: A Focus on Senescence. Biochim Biophys Acta (BBA) - Mol Cell Res (2015) 1853:1974–9. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2015.03.005

74. Danese A, Patergnani S, Bonora M, Wieckowski MR, Previati M, Giorgi C, et al. Calcium Regulates Cell Death in Cancer: Roles of the Mitochondria and Mitochondria-Associated Membranes (MAMs). Biochim Biophys Acta (BBA) - Bioenergetics (2017) 1858:615–27. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2017.01.003

Keywords: calcium-sensing receptor, MAGEC2, TNBC, AP-1, breast cancer, cell proliferation, cell motility, calcium signaling

Citation: Beasley HK, Widatalla SE, Whalen DS, Williams SD, Korolkova OY, Namba C, Pratap S, Ochieng J and Sakwe AM (2022) Identification of MAGEC2/CT10 as a High Calcium-Inducible Gene in Triple-Negative Breast Cancer. Front. Endocrinol. 13:816598. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2022.816598

Received: 16 November 2021; Accepted: 17 January 2022;

Published: 10 March 2022.

Edited by:

Chandi C. Mandal, Central University of Rajasthan, IndiaReviewed by:

Wei Zhang, Zhejiang Provincial People’s Hospital, ChinaHaoran Zhang, Tianjin Medical University, China

Copyright © 2022 Beasley, Widatalla, Whalen, Williams, Korolkova, Namba, Pratap, Ochieng and Sakwe. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Amos M. Sakwe, asakwe@mmc.edu

Heather K. Beasley

Heather K. Beasley Sarrah E. Widatalla

Sarrah E. Widatalla Diva S. Whalen1

Diva S. Whalen1 Stephen D. Williams

Stephen D. Williams Olga Y. Korolkova

Olga Y. Korolkova Clementine Namba

Clementine Namba Siddharth Pratap

Siddharth Pratap Josiah Ochieng

Josiah Ochieng Amos M. Sakwe

Amos M. Sakwe