Emotional complexity of fan-controlled comments: Affective labor of fans of high-popularity Chinese stars

- School of Media and Communication, Shanghai Jiao Tong University, Shanghai, China

In China, fan participation in media production is becoming more mainstream and diverse, and fan groups themselves are developing perceptible emotional attributes; thus, studies on affective labor involving fans are gradually increasing in number. Fan-controlled comments are a feature of fan culture that has received much attention due to their rapid growth and influence. This study uses sentiment analysis and keyword analysis to examine the main types of “emotions” felt by today's fans of highly popular stars and classifies them into four categories: idols, fan communities, the self, and the outside world. Both positive and negative emotions coexist. The study found that fans engage in this kind of obligatory affective labor, creating second-hand exchanges for personal spiritual enrichment, and focusing more on building and expressing emotions. In addition, as affective laborers, they gain a sense of belonging to a fan community and form group symbols because of their shared emotions and concerns. Throughout the process of controlling comments, the time and energy of the fan groups are consumed, their emotions are controlled, and their behavior is restrained; however, the immediate purpose they want to achieve is not achieved. What seems to be an active choice is a trap of alienated labor, bound, and controlled by forces.

1. Introduction

Media discourse has long been considered to profoundly influence social norms and ideologies. However, the Internet has extensively blurred the boundaries between media and private discourse over the past two decades. The convenience and uniformity of the Internet have allowed ordinary people to participate in media production, and the Web has provided opportunities and platforms for people to do so. In the age of streaming media, people can easily post information on social networks, and the Internet's ease of use and accessibility allows users to interact and engage in interactive behaviors through their comments. Fans no longer seem to be a subcultural group in the traditional sense. In China, fan participation in media production is becoming more mainstream and diverse, and fan groups themselves carry perceptible emotional attributes. Thus, the study of affective labor involving fans is gradually increasing. The purpose of fan-controlled comments is to control comments and suppress negative information. A common tactic is to make many similar comments under star-related content, so that these comments are ranked at the top, such as favorable comments and replies to positive comments, while argue with negative comments to get them below in the comments section (Jiang, 2019). Fan-controlled comments are one of the major characteristics of fan culture, and the “data fervor” they bring has given rise to ultra-high-power consumption, while the data are one of the criteria for judging whether a high-popularity star is commercially valuable, leading countless fan data laborers to voluntarily participate in Chinese capital games (Hu and Liu, 2021).

Tencent QQ Music, China's music streaming platform, has become the most popular way for young music fans to acquire and listen to music because of its decentralization, interactivity, freedom of choice, and portability, thereby creating the most active and satisfied users. The platform has a comment section where fans worldwide share their emotional experiences of the same songs with regular users in a virtual comment section. Social media has become a window for users to communicate mutually through self-expression (Literat and Kligler-Vilenchik, 2021). The term prosumer, a combination of the terms producer and consumer, was first proposed by American futurist Alvin Toffler in The Third Wave. Toffler (1984) argued that the boundary between consumers and producers is increasingly blurred and that consumers also assume the function of the producer in the process of consumption. In the context of high popularity and high commercial value, fan groups are no longer mere consumers, but combine the roles of consumers and producers. Jenkins (2006a) mentioned that fandom is a vehicle for marginalized subcultural groups (women, the young, and so on) to create a space for their cultural concerns within dominant representations. Fandom is a method of appropriating media texts and rereading them in a fashion that serves different interests. This is a way of transforming mass culture into popular culture. According to the China Top Stream Fan Circle Report (Fandom Beijing, 2020). However, Wang Yibo did not become popular until 2019, when he played the role of Lan Zhan in The Untamed, which was adapted from a serial novel with millions of fans, Master Devil. Additionally, because he and the other main character, Xiao Zhan, are handsome and fit the aesthetic that currently appeals to youth, they have caused a wave of “CP” fans. According to Ren (2021), CP is an abbreviation for coupling that was first used in Japanese ACGN fan-fiction in reference to male same-sex pairings. This has since expanded in scope. On the “Archive of Our Own” (AO3) platform, CP fans created many fictions. At the end of February 2020, Xiao Zhan's fans sparked widespread controversy by writing the romantic relationship of Wang Yibo and Xiao Zhan on AO3, which restricted the use of the website in China and caused a widespread public outcry. However, Wang Yibo retained a large group of loyal fans that supported him after the AO3 incident. Whether it concerns the products he endorses or the events he attends, his fans fully supported him. Song (2021) suggested that fan group seem to have no entry criteria for labeling themselves as fans of a particular star. However, fan group are also regulated by social groups. Both Wang Yibo's fan group and other Chinese highly popular star fan groups have well-managed community organizations, including data stations, controlled comment groups, purification groups against attacks on stars, and copywriting groups.

Liu (2014) described an interview with Xiao Zhan and Wang Yibo fans, including a circle of the CP fan community, and learned that they dedicated 16 primary schools in the names of their stars as acts of charity. In the era of streaming media, “fans” are no longer scattered; they have formed community groups and become a new form of community. Jenkins (2006b) regards media convergence as a form of sociocultural transformation. In the new media environment, the user is not only a viewer but also a participant, producing new modes of cultural production through a new social structure powered by collective intelligence, to influence the content of the communication itself as well as society. In their interactive rituals, they generate corresponding group identities and cohesion.

Duffett (2013) highlights the importance of music content in the creation and maintenance of fan culture. He argued that music fans are not just passive consumers of music content, but are active participants who create and shape their own fan cultures. He noted that music fans engage in a range of activities including attending concerts, participating in online forums, and creating fan-generated content such as fan fiction, fan art, and fan videos. He also explained how music fans develop strong attachments to the music they love and how this attachment shapes their identity and relationships with other fans. He also acknowledged the role of technology in facilitating fan engagement and creating new forms of fan expression. Edlom and Karlsson (2021) found that a study of Robin's fans showed that his fan motivations included enjoying relationships with other fans and interacting online and offline with a common fan circle. This motive seems similar to that of Wang Yibo's fans.

Therefore, this paper takes the fan groups of the top Chinese popular star Wang Yibo as an example: the comment sections of movie theme songs posted by him on the QQ Music platform, and samples the comment sections of movie theme songs posted by American star Billie Eilish on the same platform, using keyword analysis methods and sentiment analysis methods to conduct the study.

2. Literature review

2.1. Traceability of fan emotion research

Lewis's (1992) The Adoring Audience Fan Culture and Popular Media was an early result of the study of fan culture. Jenkins (1992), in Textual Poachers: Television Fans, and Participatory Culture view fans as active text producers. Following Jenkins, Fiske (2001) in his Understanding Popular Culture points out that fans, in their communication activities, often play symbolic and cultural production roles in their communication activities. Furthermore, they can contribute to the textual production of their fan communities by transforming symbols or cultural representations into information that can be disseminated among activist groups. Zheng and Tan (2022) indicated that in practice, the criteria for fan identification might vary greatly from one context to another, because the criteria for self-identification as a fan are often different across the entire fan community. For example, many sports fans acquire their identity through family upbringing and are passed down from father to child, especially in scenarios where there are traditional regional teams (e.g., various city-based soccer teams). There are also subcultures in which fans do not have a particularly strong emotional connection to a celebrity or individual media production, but rather a genre. For example, so-called “secondary fans” of Japanese manga/anime and manga/anime culture are often not fans of a specific anime or manga but of products from the aesthetic, logic, and industrial system of the Japanese anime industry, be it manga, animation, games, or light novels.

Perhaps the most complex issue in determining the identity of “fans” belongs to the identification of fans of idol stars on Chinese social media platforms today. While some fans may call themselves so simply because they “like it”, in the strict system of online fan circles, “becoming a fan” sometimes involves complex and specific ritualized behaviors. For example, in many celebrity-fan circles, only the purchase of a certain number of cultural products, endorsements, and other peripheral goods produced by the celebrity is required to qualify as a fan and be recognized by the fan community, involving consumption in a specific way and self-identification on specific occasions. For example, on microblogging platforms, some idol fan communities do not allow fans to follow and post content from more than two idols under the same account.

Studies of fan culture in China can be traced back to the 1990s. With the development of Internet technology and the increasing maturity of streaming technology, fans have shared information about the emotional experiences of their idols within virtual communities through platforms such as streaming media, based on their love for their celebrities.

Researchers have often cited Collins's (2009) interaction ritual chain as an important theoretical basis for studying fan communities. The central mechanism of the interaction ritual chain theory is that high levels of mutual attention among ritual participants are combined with high levels of emotional connectedness, resulting in a sense of membership associated with cognitive symbols and emotional energy for each participant, making them feel confident, enthusiastic, and eager to engage in the activity. These highly ritualistic aspects culminate in the collective experience and peak of the individual's life. Collins (2009) described interaction rituals as a process with causal associations and feedback loops, of which the four key components are (1) two or more people gather in the same place and influence each other by being present, (2) boundaries are set for outsiders, (3) people's attention is focused on a common object or activity confirmed through mutual communication, and (4) people share a common emotional or affective experience.

In the Internet era, the development of the Internet and new media technologies has made it possible for people to express their emotions in real time, both face-to-face and virtually, making it possible to exchange information “without physical presence”. The popularity of technology enables almost everyone to communicate and interact via the Internet. In particular, the anonymity of the Internet provides a safety net for fans to interact, and the technology of virtual presence provides a platform for fans to communicate, identify with, and belong to a group, promoting the unity of the fan group and giving value to the growth of fans. To a certain extent, these outcomes can promote the unity of the fan base, give meaning to the values of fan growth, and promote healthy operation of the interaction chain among fans. The “virtual co-presence” of network technology breaks the previous “physical co-presence”, giving fans in different spaces and regions a “virtual” place for communication and interaction. Compared with the previous physical presence, the virtual network makes the communication and interaction of fans timelier and more convenient.

2.2. Emotions in labor

Affective labor, which originates from the Italian Autonomous Marxist School, refers to the necessary capacity of immaterial labor to produce, cover, manage, transmit, regulate, and manipulate social relations, feelings, and ideas (Nicholas, 2013). Emotional labor contains both the exploitation of workers in the “digital economy” and the potential for emancipation and subjectivity of workers in the “gift economy” (Yang, 2020). This is different from emotional labor as defined by American sociologist Arlie Hochschild, which is an emotional management behavior that people perform to maintain their image in society in line with the emotional culture of society (Hochschild, 1983).

Hochschild (1983) proposed the concept of emotional labor, which is the study of airline flight attendants' service with a smile. She found that in addition to physical and mental labor, flight attendants must also comply with the company's rules and regulations to provide emotional labor to ensure that passengers have positive feelings about the service they receive.

Affective labor is a concept similar to that proposed by Hardt (1999), which is an extension of immaterial labor to describe the emotional practice of communication between people in real or virtual situations. Guo and Li (2021) suggests that the two belong to different theoretical categories, which can easily lead to confusion of concepts. Hochschild argues that the performance of emotions in the private sphere has been commercially exploited in the public sphere and has become a tool for commercial gain. Affective labor comes into play through a set of laws that guide it by creating a sense of the rights and obligations that govern the exchange of emotions. Lazzarato (1996) proposed the concept of immaterial labor, which can be collective and even exist only in the form of networks and communication. Affective labor is a conceptual extension of immaterial labor, and Negri and Hardt argue that it is one of the most important components of immaterial labor, which includes the production of emotions, control of the production process, and the product—which is also an emotion or a state of life that underlies and generates a sense of connection and belonging to the outside world.

Yang (2020) pointed out that fans do not develop a unified class consciousness or cultural self-consciousness in affective labor, even if they take the initiative to control comments, make data, and so on. This does not mean that they gain the emancipation of subjectivity; rather, such affective labor refers to gaining the initiative. Further, there are certain differences between emotional and affective labor in the processes of production and exploitation. From the perspective of Autonomist Marxism, Terranova (2000) introduces the concept of “digital labor” to describe the pervasive, conscious, and voluntary online behavior of Internet users that is decoupled from the capitalist pay system (unpaid) and that feels pleasurable. Applying Marx's definition of labor and utility value, Zhu and Huang (2020) point out that both satisfy people's specific emotional needs, but the emotional use value in affective labor not only satisfies people's needs but also provides a certain usefulness and creates use value in terms of political economy through the goods produced by capital.

This study explores the former type of affective labor. The “affective labor” shared between fans and idols is the key to the continuous interaction between them and the generation of digital labor. In one instance, idols produce a series of “fan welfare” actions and behaviors that allow fans to enter imaginary virtual intimacy. In contrast, fans consciously use social media to form highly organized and disciplined support groups and then solidify and reinforce their relationship with idols through a variety of support activities. In addition, fans form and enhance peer friendships through collaborative teamwork (Chen, 2018). The interaction between fans from different regions is based on the condition of a common favorite star, and group identification allows them to establish their own virtual intimacy, which is maintained by a new type of affective labor.

“Alienation” is one of the most important concepts in Marx's political and economic critique. After considering the process of capitalist commodity production in its entirety, Marx and Engels (1975) points out that the product produced by the worker is only a summary of his activities and production. The product is externalized and production itself is an active externalization. In turn, this externalization of labor is manifested in the worker's self-denial and self-sacrifice of labor, reflecting the alienation and compulsion of labor in the workers themselves. In other words, the worker's labor is not his own autonomous labor; it is the labor of the capitalist, and this labor itself means the loss of the worker's self. In the context of diversified media forms, fans no longer simply follow idols and worship idols and idol-related goods, but gradually participate in the production and packaging of idols and penetrate all aspects of idol growth.

2.3. Research subjects

In the past 2 years, owing to the rapid development of streaming media, the conflict between online and offline media has led the domestic and international film industries with controversy, while the difference between fan communities and ordinary users has become more obvious. In 2019, the streaming film Roma, produced by Netflix, caused great controversy and was the most nominated film at the Academy Awards that year. The theme song, “When I Was Older”, was sung by American singer-songwriter Billie Eilish. In China, the 2020 movie Lost in Russia was boycotted by industry insiders. Because of the coronavirus pandemic, it was the first movie in China to be shown online instead of in theaters, and this created much controversy. Its theme song, “Dear Mom”, was sung by Wang Yibo. After the song was released on Tencent's music platform, his fan base “controlled comments” in the song's comment section, but not all users had the same opinion about the song.

The behavior of “controlling comments” is a common practice in fandom culture, but it is a new phenomenon in the Internet environment. In addition, Wang (2023a), a highly popular Chinese star, has 40 million followers on Weibo (Wang, 2023b), a commonly used social media platform in China, as of December 2022, and 1.682 million fans on the QQ music platform, making him one of the top-ranked Chinese stars there. Checking the comment section for his “Dear Mom” song, we found that most comments were positive and favorable comments from fans (Eilish, 2023), indicative of a fan-controlled comment section. Although Billie Eilish has more fans than Wang Yibo on QQ Music, her song comment section presents a different picture, with no obvious fan-controlled comments.

Both songs served as theme songs for the controversial streaming film, thus encapsulating the theme and promoting it. The lyrical content of Wang Yibo's “Dear Mom” is meant to express deep feelings for his mother, while Billie's “When I Was Older” is more about self-expression, where the narrator seems to be alone in both loneliness and happiness and in sadness and pain. As Schubert (2013) suggested, psychology has shown that emotions expressed by music are consistent with the perceived emotions of listeners. Yu and Zhang (2022) argue that communication involved in the emotional coherence of music resonates with society, and that the emotional experience it evokes is a borderless language that elicits “empathy” and contains the ability to communicate, thus allowing people to connect and bridge effective communication. The comments on the song “When I Was Older” included those who thought the emotions expressed in the song resonated with them and those who thought the song helped them understand the movie more deeply. In the comment section of “Dear Mom”, although some listeners said the song resonated with them and reminded them of their own mothers, there were more comments from fans who praised Wang Yibo. Therefore, this study classifies Wang Yibo fans' emotions from the perspective of affective labor to better categorize the types of fans' emotions from a functional perspective. Sentiment and keyword analyses of the song comment sections of both have helped us gain a deeper understanding of the emotional labor of fans of popular Chinese stars.

3. Methods

In this digital online space, users can comment on the content they experience, reflecting on community motivation and the possibility of belonging (Waugh, 2017). Among them is the fan base, a product created in the context of the Internet that is growing in number and influence. They share their feelings online in music comment sections, and the data generated by these comments can be used to analyze the emotions they express after listening to music.

The way fans control comments create a landscape on social networks, such as unifying copies to occupy the front row of comment sections, liking and replying to positive comments, and reporting negative comments. These complex operations often overlook the negative effects of fans' emotions. The following research questions were proposed based on the previous combinations:

Q1: How much influence do stars singing on the two theme songs have on fan listeners?

Q2: What emotional characteristics do users exhibit when participating in comments on the two songs on Tencent's music platform?

Q3: Can the act of controlling comments and producing data carried out by fans on the QQ Music platform be considered a type of affective labor? Does its nature tend to be exploited or does it build and express emotions?

3.1. Research design

Sentiment analysis, also known as sentiment disposition analysis or opinion mining, refers to the use of natural language processing, text mining, and computational linguistics to identify and extract subjective information from original material, enabling the analysis of positive and negative opinions, emotions, and evaluations expressed using natural language. Sentiment analysis can be used to analyze fan comments on social media platforms or online forums in order to determine the predominant emotions expressed by fans (Xia and Shan, 2018). This information can provide valuable insights into fans' emotional experiences, including their level of satisfaction, excitement, and frustration with the content, artist, and fan community. Sentiment analysis is a popular research topic in the computer science, electronic communication, business economics, and other disciplines. According to Zhong et al. (2021), research on sentiment analysis focuses mainly on social media, online reviews, and business investments.

3.2. Data collection

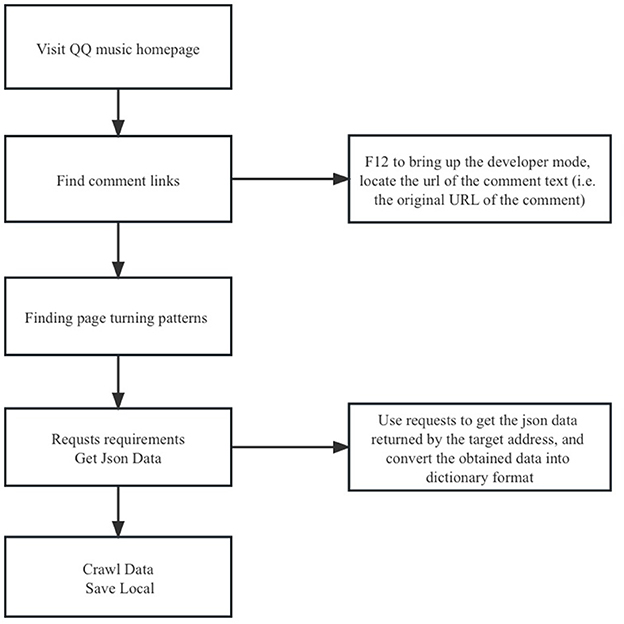

Python has many third-party libraries that inherit the power and versatility of traditional compiled languages, and manages large datasets, making it ideal for complex projects (Shelar and Huang, 2018). Python also draws on the ease of using simple scripting and interpreting languages with web crawling and data analysis capabilities, combining other programming languages. According to Zhu and Jing (2019)'s research, the crawling process has 4 steps, after finding the comment link, sending the request, getting the response content, to parse the content and save the data. On this basis, the Figure 1 was designed. First, Pycharm, a Python development tool built by JetBrains, was used for the preliminary crawling of the original comment text. The first step of this study used Python version 3.10 to write the program, run the code through Pycharm, and access the web content in TxT format via crawling, as shown below:

3.3. Data preprocessing

Post-crawling, 15,698 valid online comments for two songs were crawled from 28 April to 1 May 2022 and stored in a database. Next, the comment text was preprocessed, and the program was written in Python to exclude QQ Music user IDs while retaining the comment text content.

3.4. Research analysis

The following analytical operations were performed on the collected review texts:

(1) Sentiment analysis was performed using the Natural Language Toolkit (NLTK) and Jieba to calculate the sentiment tendencies of the two song reviews.

(2) Plotting the sentiment polarity distribution and visualizing the data.

(3) Word-frequency calculation using Jieba and word-cloud technology.

(4) Mining the specific sentiments behind review texts using word-frequency ranking and word-cloud graphs.

4. Results

4.1. Python sentiment analysis

4.1.1. QQ music comments text sentiment scores

Natural language processing (NLP) research relies heavily on sentiment analysis and opinion mining (Li and Wu, 2010). NLTK is a popular NLP library that uses NLTK to evaluate whether comments in a collected database are positive, negative, or neutral.

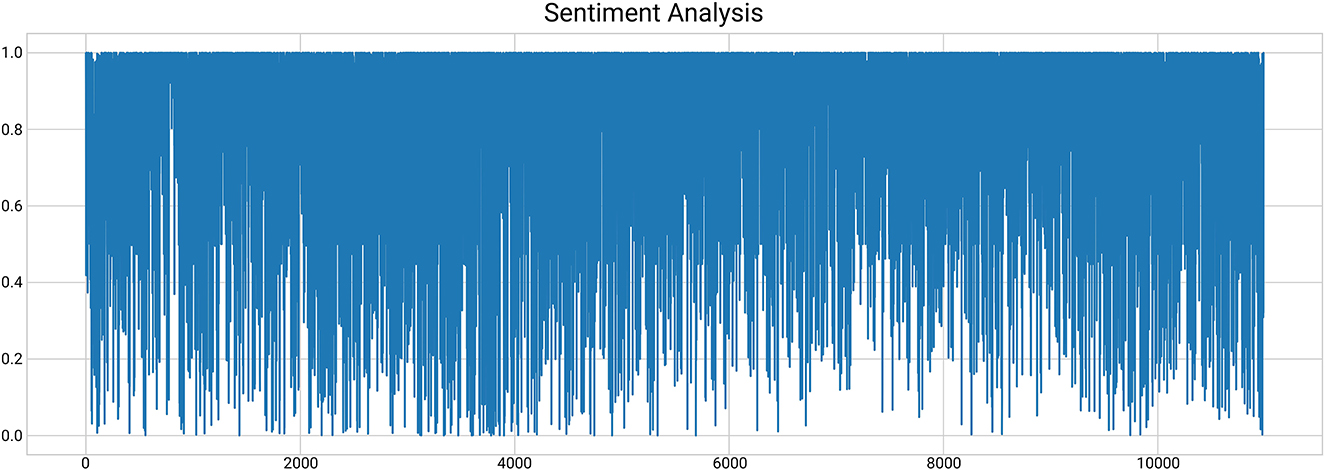

The scoring interval was 0–1, and the sentiment intensity of each comment was classified as positive, negative, or neutral. Each comment was read and analyzed for sentiment values, and a value between 0 and 1 was generated. When the value is >0.5, the sentiment polarity of the comment is positively biased; when the score is <0.5, the sentiment polarity is negatively biased. When the value was further increased from 0.5, it was more emotionally biased.

The visualization results of sentiment analysis of the comment-crawl data for the two songs are shown in Figure 2. Notably, the positive fetch values were remarkably high with strong emotional colors. There were some negative fetches, but fewer than positive ones, indicating that most users praised the experience of the two songs, showing positive emotional characteristics, with relatively few neutral comments that did not express emotional polarity. The comments also show polarization but are more positive than negative, indicating that the two songs are well-liked by QQ music users.

4.2. Word frequency

4.2.1. Word-frequency statistics for sentiment analysis of Jieba and word-cloud combinations

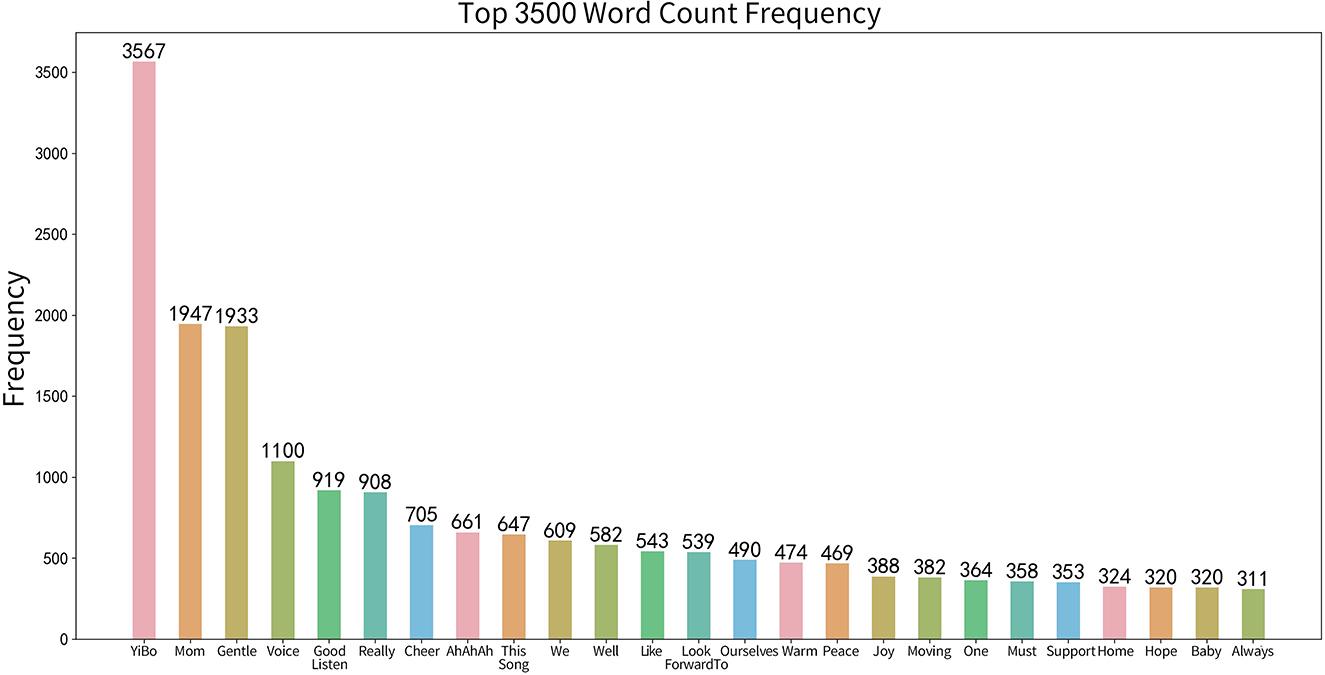

Shi (2020) mentioned the Jieba Chinese tool is a widely used and effective open-source word-splitting tool with an integrated Python library that is easy and convenient. Although NLTK has been more proficient in applying emotional tendencies to English comments, it is still necessary for Chinese word expressions to disassemble Chinese comments with the help of a word-splitter and then delve into emotionally focused hot words obtained through word-frequency statistics. Keywords appearing at a frequency of 3,500 or more were classified as positive, neutral, or negative (according to the user's understanding).

Positive: Yibo, mom, gentle, good listen, cheer, ah ah ah, voice, expect, warm, joy, moving, hope, like, baby.

Neutral: really, this song, yourself, one, definitely, home, always.

Negative: none.

Positive sentiment was mainly related to the stars' work and the users' moods, especially fans, while the neutral and negative keywords clearly showed that the fan community has a different, appreciative, and critical attitude toward the text than the general users who maintain their distance (Fiske, 2001). The negative keyword “plagiarism” did not appear until word frequency 143, where it was mentioned that the composition of the song “Dear Mom” is highly similar to “Daddy” by the British singing group, Coldplay.

The rapid development of the Internet has provided a technological guarantee for the gathering of fan communities, and Lull (2012) mentioned that modern technology has reconstructed the distance of culture in time and space so that people who do not know each other are united by common passions and the same views, forming an “interpretive community”. Xu and Guo (2022) explained that fan communities share a common idol, find an organization, come together through individual emotional expressions, and use instant communication technology and social media to communicate in a dislocated time and space, thus interacting in a virtual environment. People's images and behaviors are often hidden in this environment, presented only in words and images, because the transmission of emotions is no longer face-to-face but in the corresponding media environment, solving the disadvantages of time and space so that participants in different spatial areas can also gain a sense of identity and belonging in the interaction (Wang, 2020).

The word-frequency graph (Figure 3) shows that the most common word was “Yibo”, while other words, such as “mom,” “gentle,” and “voice,” were frequently used. In the chart of the frequency of comments on the two songs, “Yibo” occupied first place, while the frequency of another singer's name, Billie (Eilish; “Bili” in Chinese), was only 11th. The frequency of “mom” was 1,947, but the frequency of “Roma” was only 11, showing that the Chinese idol stars' fan communities are uniform in their behavior of “controlling comments” and “making data”.

Meanwhile, analyzing the keywords and crawlers' comments demonstrates that the Chinese fan community for foreign stars is not as strong as that for Chinese idols. These behaviors correspond to important components of Collins's (2009) interaction ritual chain theory, in which fans use their common favorite celebrity objects as source texts to create and share subtexts and meanings with the commenting community. Through this sharing behavior, they experience pleasure and emotional resonance. Ritual interactions between groups manifest personal emotions generated by group members, which are transmitted among members to form group feelings that become the core of group cohesion. Moreover, in this fan interpretive community, fans are participants who use new technologies and are enthusiastic about the web.

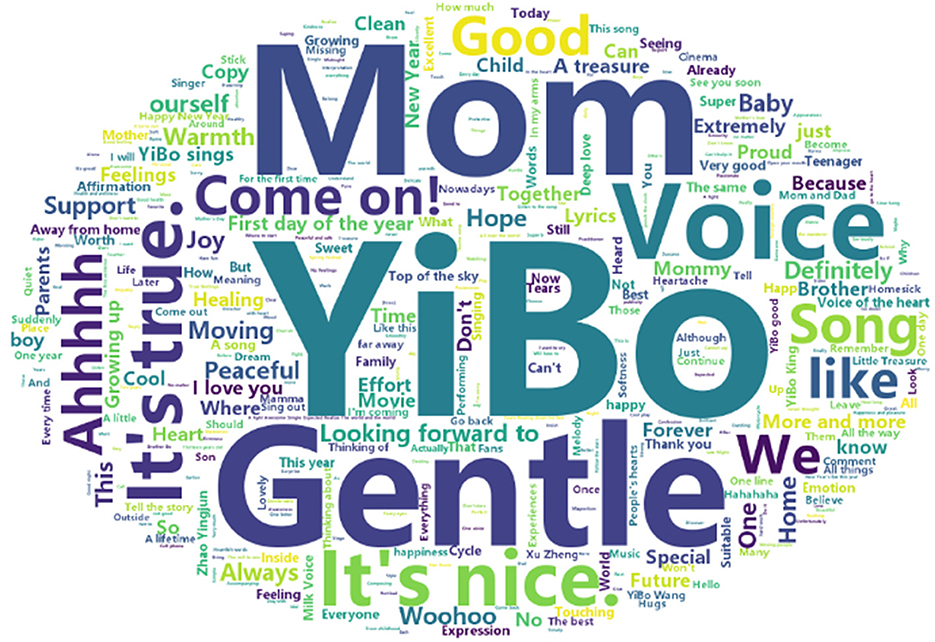

To further analyze the crawled text, this study combined Jieba word frequency analysis in Python with word cloud visualizations which, from the perspective of word frequency, could achieve a more intuitive sentiment analysis. As shown in the word visualization cloud chart in Figure 4, word frequency was distributed by font size and the lexical nature of the high-frequency words analyzed was unified in the sentiment analysis results. Among the keywords in Figures 3, 4, “Yibo,” “really,” “we,” “like,” and other high-frequency words showed the identity of fans and their liking for their idols, inspiring emotions through understanding of and identification with their idols. The keywords clearly show traces of Wang Yibo's fans' affective labor, because the frequency of the words in front of the ranking is uniform, especially the word “Yibo”, showing positive emotions. This indicates that this is not done by individual fans but by an organized group of fans collectively. In contrast to Wang Yibo's fan base, Billie Eilish's Chinese fan base is not as unified and disciplined as Wang Yibo's because of the differences in country, culture, language, etc., since she is an American star.

Fans, as “active audiences”, are not imprisoned by the ideological hegemony of capitalism, but they play the role of “laborers” and become power laborers in the whole popular culture industry, and eventually gain profits from the capital. With the development of Internet technology, the Internet has had a deeper and more profound impact on people's lifestyles. Internet culture is also changing people's thoughts, behavioral patterns, and values, creating a new social phenomenon and cultural form. For example, Zhang and Negus (2020) mentioned that fan “data fervor has given female fans a sense of control along with a sense of accomplishment, certainty, and confidence.

Based on the previous analysis, Wang Yibo's fans overcame the limitations of time and space within power differences to unite as a decentralized online community to control comments, likes, interactions, and social behaviors on the QQ music platform, thereby achieving self-positioning and identity. Fans buy and watch movies featuring Wang Yibo, download their movie theme songs, and help the star to promote them on the Internet, as secondary creation is a kind of consumer behavior in which they engage in such obligatory emotional labor and exchange secondary creation for personal spiritual enrichment, which tends to be more of an emotional establishment and expression.

4.3. Keyword analysis

As shown in the word visualization cloud chart, fans' feelings toward their idols were relatively similar, and these emotions were all intertwined. According to the word cloud chart, we find that the main keywords are “Mom,” “Yibo,” “Gentle,” and others. After hiding these positive words, we obtain neutral words like “Looking forward to,” “Thank you,” “Hope,” etc. After continuing to hide words, we obtain negative words such as “Zhao Yingjun”, whichis “Dear Moms” creator (as it was noted by netizens that “Dear Mom” copied Coldplay's “Daddy”), “Copy”, and “Sick”. Therefore, we combined the previously crawled comments after subdividing and organizing them into the following four categories, as presented in Table 1.

In this study, fan emotions were divided into positive and negative. They are divided into several parts: idols, the fan community, themselves, and the external community.

With idols, fans generate emotions such as “like” moving, “like” happy, and “like” through positive texts related to idols. When appreciating idols, they often have a filtered perspective, and in the interactive behaviors such as making controlled comments or secondary creation of idol-related texts, they realize their fantasies and generate a sense of access to virtual relationships, giving rise to various identities such as “mom fans” and “girlfriend fans”.

For fan communities, the Internet provides a platform for fans to communicate with each other, regardless of time and space, where fans communicate and interact with each other, thus generating emotional resonance to gain a sense of connection and belonging.

For themselves, fans feel a sense of pride through complimentary texts. They believe that the achievements of their idols (charts, box office, awards, or even making a popular movie or singing a popular song) are relevant to them, and when fans are proud of their idols, they also project this pride onto themselves.

Externally, fans absolutely defend their idols when stars experience what they perceive as injustice, or when their interests are compromised. Venting anger usually takes the form of conflicts with other users or groups, such as name-calling and the continued control of comments.

The interactive content of the categories showed that emotional connections further generated a sense of identity among fans. They build a new sense of self in the process of deeply loving Wang Yibo. For example, when Wang Yibo's music ranked high on the music charts, they felt proud as if it had been their accomplishment. Conversely, if Wang Yibo were maligned, they would unite and fight against the attack as if they were the ones being abused. For instance, when Wang Yibo's music was questioned, they commented on persuading the other side to explain that Wang Yibo without any problems. With fast-paced social development, people have been under pressure from all sides. The development of the Internet has brought power to fans. Baym and Burnett (2009) points out that fan participation is real and has never been more important or valuable. They have become gatekeepers, filters, and influencers on a scale that has not previously been achieved in the Internet era. The ideal love that is unavailable in real life and the benefits of honor that are unreachable in the professional arena can be achieved by supporting celebrities and their conduct.

5. Discussion

The American scholar Hardt (1999) used the concept of affective labor to describe the act of putting people's emotions into practice in real or virtual sexual exchanges and communications, arguing that the entertainment and similar cultural industries focus on the production or manipulation of emotions. In this Internet ecology, celebrity icons serve as “bait” to attract fans to move in and start producing actions. According to data support, fans continue to engage in affective labor and are willing to work hard in an affective labor factory based on the virtual relationships and emotional connections they conceive with their idols. Based on the QQ Music platform alone, the results of the word-frequency ranking and word cloud again showed that the influence of the Wang Yibo on his fans was quite deep in “Dear Mom”, while the influence of Billie Eilish on her Chinese fans was much less. Usually, each comment on QQ Music is a sentence or paragraph containing words, and after removing the stop words, the remaining text contains different emotions. The above sentiment analysis of QQ Music comment text made it easy to see that although positive sentiment was greater than neutral or negative sentiment, the three sentiments coexisted and belonged to a complex set of various sentiments.

Through the classification of emotional categories, many fans in the comment section controlled their comment ranking, influencing each other while including their mutual communication experiences to generate pleasure and emotional resonance. This “fanatic” behaviors made people focus only on Wang Yibo himself while the comments of the fan group “controlled” the comments, perhaps ignoring the work itself.

Liu (2014) indicated that interactive rituals are conducted because of common concerns, enabling authentic emotions to form a group symbol. When the identity of group members is strengthened, their sense of belonging and solidarity is also enhanced. As rituals continue to advance, the emotional energy transmitted between individuals becomes stronger, driving interactive rituals to continue and strengthen the identity of group members, thereby forming a loop of interactive rituals.

In particular, when fans adopt behavior consistent with the outside world, they gain a greater sense of belonging and connection than in the past. In addition, membership in fan groups increases fans' sense of security in their lives. However, after the communities established by hobbies meet the needs of personal identity—social needs, the public's “desirability needs” gradually emerge, and fans actively join the process of content production in social media and dissemination; the content and data produced by them will eventually be free of charge. The content and data they produce are owned for free, thus contributing to the appreciation of digital capital. In other words, fan groups will continue to engage in unpaid work to satisfy their need for a sense of belonging and identity (Li, 2020).

From the fans' point of view, idols, as commodities produced with their input, are supposed to determine the future direction of development, and their operations cannot deviate from fans' ideas, as they need to operate as idols according to fans' will. Therefore, idols must be born as commodities that serve fans in their image. Fans place their own ideas of perfection on their idols; thus, their words, behavior, and appearance need to be within the range of what fans accept with expectations; otherwise, conflicts will arise, leading to defection cases. Idols that appear contrary to fans' expectations can be controversial, even if their words and behavior do not violate moral principles or laws. By losing the right to express themselves, idol personas become homogenized, presenting the public with a uniform image of sunshine, gentleness, and politeness, which often leads to the collapse of the so-called personas. Different personalities are forced to be the same, resulting in a lack of personal meaning, erosion, and suppression of hidden personality traits and values (Lee, 2021).

Fan groups participate in market operations by virtue of their consumption input, which has greatly influenced industries such as film, television, and music,. They influence the entire industrial ecology through voting, charting, and controlling comments. The rating of works is no longer based on the good or bad quality of the works but has become a product of fan influence (Chen, 2018). In addition, fan groups have the advantage of numbers, and such manipulation of the industry with a strong subjective will to control comments and give high scores to idols' films or TV works can produce a series of negative consequences. Hu and Liu (2021) mentioned that fans create high popularity through explosive topics day and night on the network media, bringing a lot of revenue to the media capital without getting any substantial compensation for themselves. In contrast, the labor of fans in the network media is more emotional, and the feedback they receive from investing their emotions is immaterial. The exploitation of capital is also immaterial; however, fans are completely manipulated by capital in an invisible manner. The affective labor, physical labor, and consumption power that fans put into this are all manifestations of their free labor. The value of fan data labor lies not only in its reproduction of meaning, but also in the fact that fans, with their consumption power, become the vane of the mass media and capital market, thus becoming a huge resource for commercial capital to exploit.

As audiences of entertainment cultures, fans have more power to speak, which is not a bad thing. Through the accumulation of personal experiences, the group can provide more useful opinions to the idols to achieve a positive interaction and incentive mechanism, and the idols' products are reviewed by fans, who make choices and engage in critical behaviors to better develop idols. However, as idols cannot show their personal will and must satisfy the needs of their fans if they want more opportunities for development, the power of unilateral control without restraint can easily be alienated and degraded.

6. Conclusion

As the entertainment industry continues to evolve, fans drive the China entertainment market, leading to a certain degree of confusion. Based on Certeau's idea of “poaching”, Jenkins (1992) emphasized the subjectivity of fans who loot popular culture, seize the resources available to them, and create related secondary works as part of their own cultural creation and social exchange. As some scholars have argued about the theory of the “precariat”, the inherent rebellious character of fans as a subcultural group, there is great potential for fans to seek political subjects in new domains. The significance or value of these data-based production acts of charting and controlled commentary is that, in addition to reflecting the dynamic nature of audiences in the new media age and the diversity and even rebelliousness of interpreting the meaning of texts, fans guide and drive the consumer social market using collective action. Baldwin and McCracken (1999) also critiqued the over-interpretation of fan behavior and said that we should think about pleasure in terms of pleasure itself instead of over-rationalizing the fanatical behaviors of fans as something else.

The instrumental rationality and economic principles of modern society describe the world as a tradable marketplace that can be linked by money and efficiency. The metaphor of communication as a means of transportation suggests the exchangeability of information as well as the commodity character of people. At the same time, we cannot ignore the sacredness of communication activities for our sociocultural interactions, integration, and emotional connections, as highlighted in the ritual view of communication. Communication activities cannot be ignored in the context of fan-culture communication communities, where emotions and interests are core factors. The study of fan culture is by no means limited to a uniform, simplistic characterization and radical critique of fans. Fan culture is not just a group or a mass cultural ecology but also an expression of and pursuit of emotions by individuals.

The popularity of the media forms of music streaming application platforms has created different types of access to streaming movie music. When a series of fan community behaviors appeared in the music comment section, the meaning of the film and the music itself, which should have been there, changed. The fan phenomenon can reflect the social mentality of the younger generation in the current Chinese entertainment industry chain, which in turn is the “vane” and “barometer” of social development. Using sentiment analysis and keyword analysis, this study examines the main types of “emotions” of today's popular fans and classifies them into four categories: idols, fan communities, the self, and the outside world. Both positive and negative emotions coexist. This study found that fans engage in this kind of obligatory affective labor, creating a second-hand exchange for personal spiritual enrichment and focusing more on building and expressing emotions. In addition, as affective laborers, they not only form group symbols because of their shared emotions and concerns but also gain a sense of belonging to a fan community. Fan identity provides individuals with an opportunity for identity “mobility.” Through fans' individual and group identities, individuals can enrich, extend, and transform their self-concepts, thereby enhancing their sense of belonging to a group through social support. Individuals can even gain a sense of accomplishment through fan behavior, which is difficult to obtain in daily life. These are positive experiences that a fan culture brings people. Grossberg (1992) suggests that fans explore and shape their own subjective emotions in cultural practices and that the unity of the “producer-consumer” identity allows them to move beyond mere incorporation and resistance to the formation and reorganization of identity in everyday life in strange performances.

However, over time, a single social role may put people under more psychological strain and may not meet their greater psychological needs for self-diversity and self-actualization. Through the fan phenomenon, we can observe how the high degree of “mobility” of identity present today, together with the growth of the Internet technology sector, can have a positive influence on people's psychology. Fan-controlled comments have drawn attention owing to their rapid emergence and influence as a type of behavioral expression of fan culture. By examining the logic and psychological motives of fan-controlled comments, it is easy to find that the time and energy of fan groups are consumed, their emotions are controlled, and their behavior is restrained; however, the direct purpose they want to achieve is not accomplished. The seemingly active choice is trapped in alienated labor, bound, and controlled by the power of all parties. In this light, the psychological needs and motivations of individuals behind the fan phenomenon are crucial for building a healthy society and are worthy of further reflection.

6.1. Research limitations

First, the scope of the study was narrow. This study considers Wang Yibo's fan base as the main research object and focuses on the comment control behavior of fans on the QQ Music platform, not considering other social media platforms, such as Weibo and TikTok. Different social media platforms will reflect different characteristics; using QQ Music as the sole platform will lead to a certain limitation of research results. Second, the research methods used in this study were sentiment and keyword analyses, among which keyword analysis was easily influenced by personal subjectivity, which may have undermined the objectivity and scientific rigor of the study to a certain extent. In addition, the research in this study is not thorough enough, focusing only on the comment control behavior of Wang Yibo's fan group, and fails to consider the relationship between the parties behind comment control by fans in a comprehensive manner. However, there is still a need to study this phenomenon in a larger and more thorough framework.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

The author confirms being the sole contributor of this work and has approved it for publication.

Conflict of interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fcomm.2023.1006563/full#supplementary-material

References

Baym, N. K., and Burnett, R. (2009). Amateur experts international fan labor in Swedish independent music. Int. J. Cult. Stud. 12, 433–449. doi: 10.1177/1367877909337857

Chen, L. (2018). Emotional labor and intake – A study on Baidu posting K-pop fans' pooling of funds for support. Cult. Stud. 3, 123−134.

Collins, R. (2009). Interaction Ritual Chains. Translated by J. Lin, P. Wang, and L. Song. Beijing: The Commercial Press.

Duffett, M. (2013). Understanding Fandom: An Introduction to the Study of Media Fan Culture. New York, NY: Bloomsbury Academic.

Edlom, J., and Karlsson, J. (2021). Keep the fire burning: exploring the hierarchies of music fandom and the motivations of superfans. Media Commun. 9, 127–128. doi: 10.17645/mac.v9i3.4013

Eilish, B. (2023). Official Billie Eillish QQ music. Availaable online at: https://c.y.qq.com/base/fcgi-bin/u?__=jzqS1r (accessed February 3, 2023).

Fandom Beijing (2020). China Top Stream Fan Circle Report. Digital. Available online at: https://www.digitaling.com/articles/265600.html (accessed February 3, 2022).

Fiske, J. (2001). Understanding Popular Culture. Translated by X. Wang and W. Song. Beijing: Central Compilation and Translation Press.

Guo, S. A., and Li, H. (2021). Affective labor and emotional labor: conceptual misuse, discernment, and intersectionality interpretation. Press Circ. 12, 56–68.

Hochschild, A. R. (1983). The Managed Heart: Commercialization of Human Feeling. Berkeley, CA; Los Angeles, CA: University of California Press.

Hu, Y., and Liu, C. (2021). The mirror of reality: the social symptom behind the rice circle culture. J. Bimonth. 0, 65–79 + 119.

Jenkins, H. (1992). Textual Poachers: Television Fans and Participatory Culture. New York, NY: Routledge.

Jenkins, H. (2006a). Fans, Bloggers, and Gamers: Exploring Participatory Culture. New York, NY: New York University Press.

Jenkins, H. (2006b). Convergence Culture: Where Old and New Media Collide. New York, NY: New York University Press.

Jiang, L. (2019). A Study of Fan Phenomena on Sina Weibo: KongPing and LunBo. Available online at: https://kns.cnki.net/KCMS/detail/detail.aspx?dbname=CMFD202001&filename=1019221316.nh (accessed February 3, 2022).

Lazzarato, M. (1996). “Immaterial labor,” in Radical Thought in Italy, eds P. Virno, and M. Hardt (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press), 133–147.

Lee, M. (2021). From “emotional labor” to “overconsumption”-reconstruction of idol-fan relationship and power alienation. J. News Res. 11, 33–35.

Li, N., and Wu, D. D. (2010). Using text mining and sentiment analysis for online forums hotspot detection and forecast. Decis. Support Syst. 48, 354–368. doi: 10.1016/j.dss.2009.09.003

Li, Y. (2020). Forms of digital labor on social platforms and their motivating mechanisms. New Media Res. 6, 10–12.

Literat, I., and Kligler-Vilenchik, N. (2021). How popular culture prompts youth collective political expression and cross-cutting political talk on social media: a cross-platform analysis. Soc. Media Soc. 7, 1–14. doi: 10.1177/20563051211008821

Liu, S. (2014). Cultural communication analysis of the program “Who's Talking”, an emotional mediation program in the view of ritual. Mod. Commun. 2, 151–152.

Lull, J. (2012). Media Communication, Culture: A Global Approach. Trans. H. Dong. Beijing: The Commercial Press.

Nicholas, C. (2013). Watching nightlife: affective labor, social media, and Surveillance. Telev. New Media.15, 250–265. doi: 10.1177/1527476413498121

Ren, X. (2021). The Triumph of Participation: A Study on the Media Participation Behavior of CP Fans in Social Media. Available online at: https://kns.cnki.net/KCMS/detail/detail.aspx?dbname=CMFD202201&filename=1021030137.nh (accessed February 3, 2023).

Schubert, E. (2013). Emotion felt by the listener and expressed by the music: literature review and theoretical investigation. Front. Psychol. 4, 837. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2013.00837

Shelar, A., and Huang, C.-Y. (2018). “Sentiment analysis of twitter data,” in Proceedings of the International Conference on Computational Science and Computational Intelligence (Las Vegas, CA), 1301–1302.

Shi, S. (2020). Implementation of a Chinese text corpus preprocessing module based on Jieba. Comput. Knowl. Technol. 16. doi: 10.14004/j.cnki.ckt.2020.1579

Song, X.-N. (2021). Research on Interaction Practices and Identity Among Fan Groups. Available online at: https://kns.cnki.net/KCMS/detail/detail.aspx?dbname=CMFD202202&filename=1021030139.nh (accessed February 3, 2023).

Terranova, T. (2000). Free labor: producing culture for the digital economy. Soc. Text 18, 33–58. doi: 10.1215/01642472-18-2_63-33

Wang, Y. (2020). The formation of emotional labor and its control in online fan communities – The case of Moonlight station subs. Study Pract. 10, 108–119.

Wang, Y. (2023a). Official Wang Yibo Weibo. Available online at: https://weibo.com (accessed February 3, 2023).

Wang, Y. (2023b). Official Wang Yibo QQ Music. Available online at: https://c.y.qq.com/base/fcgi-bin/u?__=vUfssdz (accessed February 3, 2023).

Waugh, M. (2017). My laptop is an extension of my memory and self: post-internet identity, virtual intimacy and digital queering in online popular music. Pop. Mus. 36, 233–251. doi: 10.1017/S0261143017000083

Xia, Y., and Shan, X. (2018). Simple text sentiment analysis based on Python. Yinshan Acad. J. 32, 58–59.

Xu, Z., and Guo, X. (2022). Symbols and interactions: the construction of collective identity in “fan groups.” Comp. Stud. Cult. Innov. 5, 63–66.

Yang, X. (2020). A critique of the political economy of communication of emotional labor – A case study of L backers. Shanghai J. Rev. 9, 14–24.

Yu, G., and Zhang, J. (2022). Music as a medium: A new value paradigm for musical elements in communication. Mod. Comm. 3, 84–90.

Zhang, Q., and Negus, K. (2020). East Asian pop music idol production and the emergence of data fandom in China. Int. J. Cult. Stud. 23, 493–511. doi: 10.1177/1367877920904064

Zheng, X., and Tan, J. (2022). Identification and performance: a study of fan culture in the Internet era. Soc. Sci. China 1, 128–137+160.

Zhong, J., Liu, W., Wang, S., and Yang, H. (2021). A review of text sentiment analysis methods and applications. Data Anal. Knowl. Disc. 6, 1–13.

Zhu, Y., and Huang, S. (2020). The emotional engagement of labor: the value and production of emotions in the digital age. J. Party School CPC Ningbo Mu. Commit. 2, 32–40+121.

Keywords: affective labor, Chinese fan community, media, emotion, sentiment analysis, keyword analysis

Citation: Wei Y (2023) Emotional complexity of fan-controlled comments: Affective labor of fans of high-popularity Chinese stars. Front. Commun. 8:1006563. doi: 10.3389/fcomm.2023.1006563

Received: 29 July 2022; Accepted: 06 March 2023;

Published: 04 April 2023.

Edited by:

Cassian Scruggs Sparkes-Vian, University of the West of England, United KingdomReviewed by:

Karl Spracklen, Leeds Beckett University, United KingdomJessica Edlom, Karlstad University, Sweden

Copyright © 2023 Wei. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Yuruo Wei, 234986160@qq.com

Yuruo Wei

Yuruo Wei