- Department of Ecology and Evolution, University of Lausanne, Lausanne, Switzerland

Molecular evolution is being revolutionized by high-throughput sequencing allowing an increased amount of genome-wide data available for multiple species. While base composition summarized by GC-content is one of the first metrics measured in genomes, its genomic distribution is a frequently neglected feature in downstream analyses based on DNA sequence comparisons. Here, we show how base composition heterogeneity among loci and taxa can bias common molecular evolution analyses such as phylogenetic tree reconstruction, detection of natural selection and estimation of codon usage. We then discuss the biological, technical and methodological causes of these GC-associated biases and suggest approaches to overcome them.

Introduction

GC-content is shaped by a complex balance among mutation, selection, recombination, and genetic drift (Bulmer, 1991; Eyre-Walker and Hurst, 2001; Duret et al., 2002). As a consequence of variation in this subtle balance, it has been observed that GC-content varies considerably at two levels: (i) among genomes from different species and (ii) along chromosomes of a single species (Bernardi et al., 1985). Among species, the average genomic GC-content ranges from 13 to 75% (Pagani et al., 2011). Within the same genome, large chromosomal regions can also greatly differ in their nucleotide composition as first described in humans (Bernardi et al., 1985). For instance, GC-content is distributed across the human genome over successive long stretches of >100 kb that can be either GC-rich (with a GC-content ∼60%) or GC-poor (with a GC-content ∼35%; International Human Genome Sequencing Consortium, 2001).

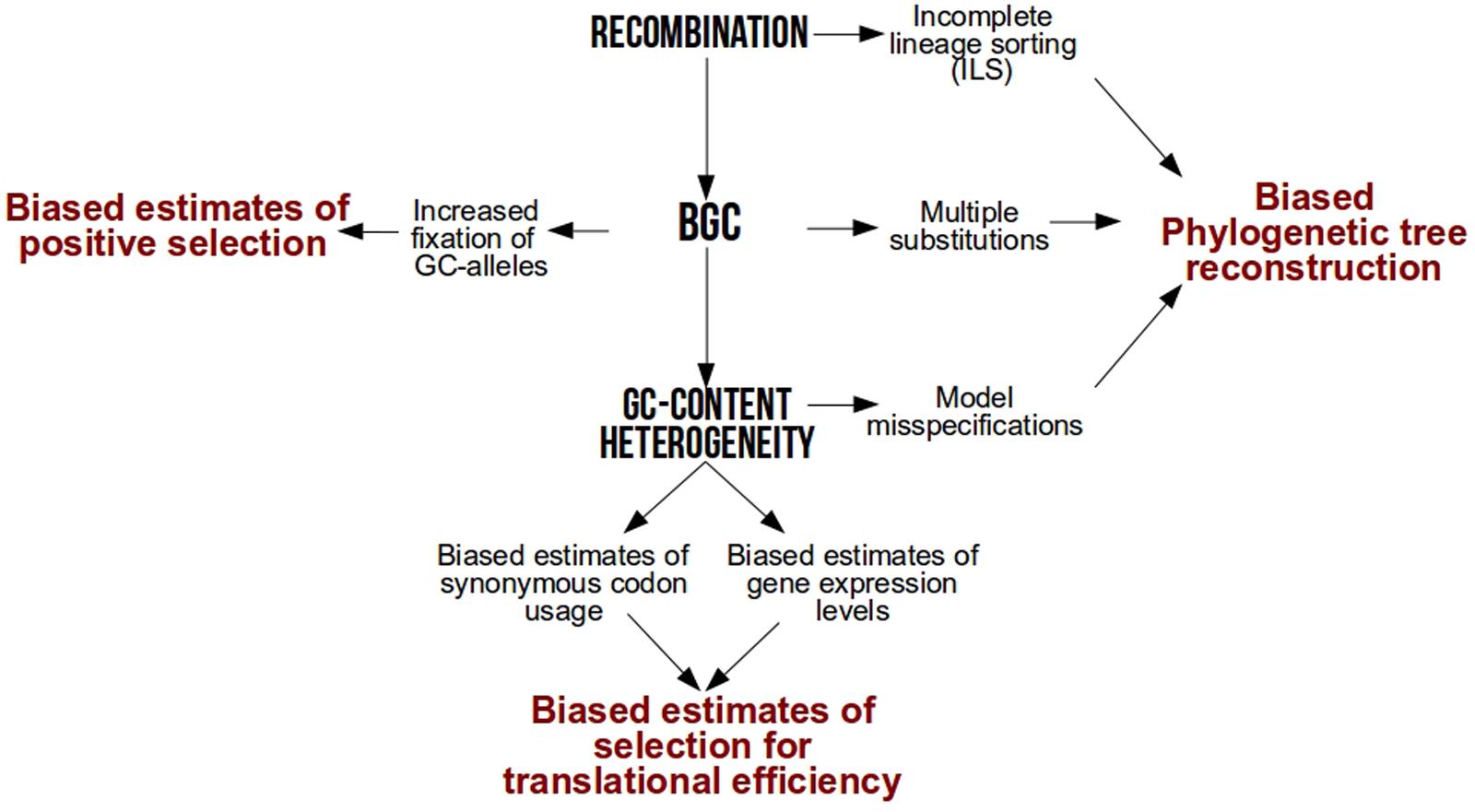

After several years of debate among neutral or selective hypotheses [reviewed in Duret and Galtier (2009)], it is now widely accepted that one of the major drivers of base composition heterogeneity is GC-biased gene conversion (gBGC), a repair bias that favors GC over AT alleles during meiotic recombination (Eyre-Walker, 1993; Galtier et al., 2001; Montoya-Burgos et al., 2003; Duret and Arndt, 2008; Kent et al., 2012; Arbeithuber et al., 2015; Mugal et al., 2015). As a result of this link between GC and recombination, local GC-content increases faster in genomic hotspots of recombination (Spencer, 2006) while genome-wide GC-content increases faster in species with higher recombination rates per time unit (Romiguier et al., 2010, 2013b; Figuet et al., 2014; Weber et al., 2014). By conferring a higher transmission probability of GC alleles over AT in heterozygotes, gBGC mimics natural selection but is frequently overlooked in molecular evolution studies. Here, we revisit how much intra-genomic and inter-specific variations in base composition have a strong power to bias popular analyses in molecular evolution such as phylogenetic tree reconstruction, detection of natural selection and estimation of codon usage bias (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1. Methodological biases associated to recombination, GC-biased gene conversion (BGC) and GC-content heterogeneity.

Phylogenetic Tree Reconstruction

Reconstructions of phylogenetic trees from molecular datasets are central in evolutionary biology. While initially limited to a handful of loci with limited power to resolve difficult phylogenetic relationships, phylogenetic tree reconstruction is no longer restricted by the number of genetic markers. However, some phylogenetic relationships of the Tree of Life remain unresolved (Philippe et al., 2011). This difficulty stems from the mosaic nature of genomes gathering alternative and conflicting gene trees (Degnan and Rosenberg, 2009), where some but not all loci support the true species genealogy. Determining which loci are reliable phylogenetic markers is thus one of the biggest challenges in phylogenomics. While mixed historical signals along genomes are likely to have different natures, we will here focus to issues related to base composition.

A recent phylogenomic study reported that base composition is a relevant criterion to select markers carrying unambiguous phylogenetic signal: gene GC-content (average GC% of the sequences of an alignment) and GC-heterogeneity (variance of GC% among sequences of an alignment) were proved to bias species tree reconstructions (Romiguier et al., 2013a). As illustrated with mammalian genomes, phylogenetic trees of genes located in GC-rich regions produce five times more contradicting topologies than GC-poor genes, leading to important reconstruction biases and a poor resolution for both accepted and controversial nodes. This negative analytical effects of GC-content on tree reconstructions is widespread across the tree of life, as reported in basal eukaryote lineages (Rodríguez-Ezpeleta et al., 2007), yeasts (Collins et al., 2005), beetles (Sheffield et al., 2009), bees (Romiguier et al., 2016), hexapods (Delsuc, 2003), fishes (Li and Ortí, 2007; Betancur-R et al., 2013), birds (Nabholz et al., 2011), and bats (Teeling et al., 2000). Despite the accumulating empirical evidence demonstrating the pervasiveness of base composition issues in phylogeny, the reasons underlying such strong biases are unexplored. Here, we suggest three non-mutually exclusive hypotheses to explain this negative GC-effect in phylogenomics studies.

First, some aspects of the GC-bias are likely to be due to model misspecifications. Probabilistic methods for phylogenetic reconstruction (maximum likelihood or Bayesian inference) are indeed generally based on models of sequence evolution that assume a homogeneous base composition along the tree. However, this assumption is often violated (Phillips et al., 2004). Indeed, average GC-content of an alignment correlates strongly with GC-heterogeneity among sequences as a result of variation in the dynamic of gBGC among sampled species (Romiguier et al., 2013a). Such departures from the assumption of base composition homogeneity can lead to severe biases by incorrectly grouping distantly related taxa that converge in extreme nucleotide composition on a given locus (Phillips et al., 2004). This type of issues can be, however, easily solved by model-based solutions (see last paragraph of this section for more details).

The second hypothesis proposes that incomplete lineage sorting (ILS) is more important in GC-rich than GC-poor regions. ILS is known to produce conflicts among gene trees and the species tree because of the retention of ancestral polymorphisms (Degnan and Rosenberg, 2009). At the scale of the whole genome, the amount of incompletely sorted genes increases when the time of divergence is small relative to the average effective population sizes (Clark, 1997). Genomic variation in ILS was also empirically reported to be associated to GC-content in hominid genomes (Hobolth et al., 2011). This indirect (Charlesworth et al., 1993) relationship between GC-content and ILS can be explained by the dual effects of local recombination rates on base composition and linkage disequilibrium. High local recombination rates increase GC-content through gBGC, but also decrease the effect of genetic interferences, i.e., background selection (Charlesworth et al., 1993) and hitchhiking (Smith and Haigh, 1974). By being less affected by linked selective processes, GC-rich regions are thus expected to have relatively higher effective population sizes than GC-poor regions, leading to an extended retention time of ancestral polymorphism.

The third hypothesis is that gBGC is associated to saturation in multiple substitutions. Following the rapid birth and death of local recombination hotspots, gBGC is expected to occur in short, intense episodes (Duret and Galtier, 2009) where deleterious GC substitutions are likely to occur (Necşulea et al., 2011). Following a gBGC episode, natural selection is likely to revert such deleterious substitutions through AT replacement (Galtier et al., 2009). This toggling between GC deleterious and AT compensatory substitutions at the same nucleotide site is expected to lead to homoplasy, a direct consequence of multiple substitutions causing spurious similarity not due to common ancestry (Philippe et al., 2011). This type of AT/GC toggling is expected to be particularly fast and difficult to track because of the short-life of gBGC episodes that depends on the self-destructive nature of recombination hotspots (Coop and Myers, 2007). Even at very short evolutionary scales such as the Denisovan/Modern human divergence (0.4–0.8 Myrs), local recombination hotspots are not conserved (Lesecque et al., 2014), which could imply a complete loss of phylogenetic signals due to multiple turnovers between gBGC and natural selection at larger evolutionary scales. Although genomically small (1–2 kb), these short-lived recombination hotspots tend to arise and disappear in the same genomic regions of 1–2 Mb (Duret and Galtier, 2009) exhibit homoplasy issues. Common in fast-evolving sequences, homoplasy is also at the origin of the so-called and undesired “long branch attraction artifact” (Felsenstein, 1978). Reinforcing the idea that GC-rich genes might be affected by such biases, GC-rich and GC-heterogeneous genes have fast rates of evolution (Romiguier et al., 2013a, 2016). These abnormally fast-evolving genes are then likely to cause long-branch attraction artifacts, but also more general issues related to heterotachy-driven biases (Philippe et al., 2005). Even if long-branch attraction is generally considered as a minor problem in likelihood-based phylogenetics compared to parsimony, maximum likelihood methods using GC-rich genes can have a biased support toward topologies grouping long branches together (Romiguier et al., 2013a, 2016).

One solution to cope with base composition issues is the use of models of sequence evolution that takes into account heterogeneity in GC-content (Galtier and Gouy, 1998; Foster, 2004; Blanquart and Lartillot, 2006; Boussau and Gouy, 2006; Gowri-Shankar and Rattray, 2007; Dutheil and Boussau, 2008). However, these so-called non-homogeneous models are computationally costly. Albeit useful to alleviate GC-heterogeneity issues in phylogeny, empirical studies illustrate their limits to retrieve high bootstrap supports in the most GC-heterogeneous sequences (Betancur-R et al., 2013; Romiguier et al., 2016), shedding light on other GC-dependent biases in phylogeny such as ILS and gBGC-driven homoplasy. To date, the best practice recommended to discard noisy signals in sequences is the use of non-homogeneous models and/or the use of GC-poor phylogenetic markers. In this regard, it is noteworthy that coding sequences tend to be clustered in recombination hotspots and GC-rich regions (Duret and Galtier, 2009). Consequently, the use of the rare phylogenetic markers located in AT-rich regions is recommended. This is the case of ultra-conserved non-coding elements (UCE) that have the advantage to be AT-rich and evolve particularly slowly (McCormack et al., 2012). Compared to these non-coding AT-rich markers, clusters of AT-rich coding genes in low-recombining regions could undergo a higher rate of background selection, decreasing the effective population size and then, the amount of ILS. It is noteworthy that UCE and AT-rich genes both support the same topology for the controversial rooting of placental mammals (McCormack et al., 2012; Romiguier et al., 2013a), highlighting relevance of these markers to overcome GC-biases. Other strategies might involve to compare these markers with markers that cannot be affected by recombination and gBGC, such as mitochondrial genes. Further methodological improvements could come from coalescent-based supertree methods (Liu et al., 2009) that account for ILS. By weighting the confidence in each gene tree according to the GC-content of an alignment, they may allow the integration of most of the available information and alleviate the spurious signal inherent to GC-rich markers. To date, methods computing the exact likelihood of alternative topologies are restricted to relatively simple models neglecting direct and indirect effects of background selection, selective sweep, gBGC and ILS on phylogenetic reconstruction. But these processes are now implemented in recent simulators (Haller and Messer, 2017), allowing them to be treated as nuisance parameters during computational evolution of sequences. Although such highly complex models are currently intractable by maximum likelihood approaches, the possibility to simulate them within an approximate Bayesian computation (ABC) framework (Beaumont et al., 2002; Csilléry et al., 2010a,b; Pudlo et al., 2016) could bring new methodological perspectives in phylogenetic reconstruction. ABC has been proved to be a powerful framework to compare complex evolutionary scenarios for large datasets (Roux et al., 2016), illustrating the recent improvements made in flexible machine learning algorithms. Applied to phylogenetic reconstructions, efficient computational tools like SLiM 2 are already available to simulate models with gBGC episodes and multiple substitutions along a branch as well as statistical packages to compute the probabilities of alternative scenarios (Csilléry et al., 2012; Pudlo et al., 2016). Altogether, current available softwares already provide stimulating leads for future developments in phylogeny.

Detection of Positive Selection

Identifying candidate loci for natural selection is a central goal explored by two traditional approaches in adaptation-genomics: top-down (GWA and QTL) and bottom-up (genomic scan) approaches. With the advent of high-throughput sequencing, genomic scans became a popular approach to detect candidate target of selection. Such scans have the merit to identify candidates without the a priori expectation of a candidate gene approach (Ellegren, 2014). However, they have various limitations with false-positive issues (Mallick et al., 2009; Bierne et al., 2011), narrow signatures of balancing selection (Roux et al., 2012), and over-interpretation of outlier loci (Pavlidis et al., 2012). Here, we detail how GC-content can lead to important additional bias during genome scans for detecting natural selection.

Genome scans of positive selection often rely on methods that look for lineage-specific accelerations in the protein rate of evolution. Such accelerations are classically measured through dN/dS, which calculates the excess of amino-acid substitutions (dN: non-synonymous mutation rate per site) relative to dS, the substitution rate per site used as a proxy of the neutral clock. This dN/dS ratio is generally smaller than 1, reflecting the pervasiveness of purifying selection that eliminates non-synonymous mutations to preserve the protein structure. Conversely, a dN/dS ratio greater than 1 is considered as a signature of positive selection that favors the fixation of beneficial non-synonymous mutations. From a population genetics point of view, gBGC mimics positive selection by favoring the fixation of AT- > GC mutations, regardless of their beneficial or deleterious status (Nagylaki, 1983). Because GC alleles are actively selected by the repair systems of meiotic recombination, they are over-represented in the gamete pool and benefit of increased transmission to the next generation in a similar way than beneficial mutations subject to positive selection. Consequently, many accelerations of the substitution rate attributed to positive selection during genome scans are actually due to gBGC episodes (Galtier and Duret, 2007; Berglund et al., 2009; Galtier et al., 2009; Ratnakumar et al., 2010; Kostka et al., 2012). When a mutation toward GC is deleterious, gBGC can counteract positive selection and maintain or fix deleterious alleles. High fixation rates of non-synonymous mutations at a locus should thus not be systematically interpreted as being beneficial for the fitness of the individual, particularly when considering that gBGC has been proved to be able to maintain deleterious mutations associated to human diseases (Necşulea et al., 2011; Capra et al., 2013; Lachance and Tishkoff, 2014).

Confusion between positive selection and gBGC could be avoided through two different ways. The first is by filtering the results of classical tests of positive selection and consider with caution positive selection signatures in GC-rich regions. This is particularly true for selection tests that rely more on overall evolutionary rate rather than dN/dS (Pollard et al., 2006; Kostka et al., 2012). Even if gBGC can increase dN/dS in some conditions (Galtier et al., 2009; Bolívar et al., 2015), AT- > GC mutations are more likely to happen in synonymous sites, which limits the effect of gBGC on dN/dS compared to the evolutionary rate. Several criterions can be used in both cases to differentiate gBGC from positive selection, such as the number of mutations toward GC in the surrounding non-coding regions (Galtier and Duret, 2007). The second would be to develop methods that restrict dN/dS estimations to GC-conservative substitutions in the context of codon-models aimed to detect positive selection events (Yang and Nielsen, 2002; Lartillot, 2013).

Codon Usage Bias

Popular analytical methods in molecular evolution rely on a strong assumption: synonymous mutations are neutral. GC-content at synonymous positions is frequently claimed to be exposed only to the mutation/drift equilibrium. However, natural selection was proposed to be superimposed to these two evolutionary forces at synonymous codons (Urrutia, 2003; Comeron, 2004; Plotkin et al., 2004). Although initially challenged (Williamson et al., 2005), natural selection acting on standing synonymous variation was found to be associated to gene expression level, the most expressed genes using a set of preferred codons (Comeron, 2004). This association is explained by selection for increased translational efficiency. The analysis of >1,000 genes in Drosophila demonstrated that the most used synonymous codons corresponded to the most available tRNAs in the genome (Moriyama and Powell, 1997). Translational efficiency would then be optimized by increasing the usage of the preferred synonymous codons. Such a process can be tested in coding sequences by measuring the effective number of codons (ENc) in a given gene. ENc takes a value of 61 when all codons of the genetic code (minus the three stop codons) are used without bias, and decreases to 20 (the number of amino-acids) for the most biased genes. In agreement with the hypothesis of selection for translational efficiency, population genetics analyses in Drosophila described signatures of selection on synonymous mutations (Akashi, 1995; Akashi and Schaeffer, 1997).

A study of codon usage bias in Caenorhabditis elegans, Drosophila melanogaster, and Arabidopsis thaliana has shed light on the over-expression of genes featuring codon preference, with a large predominance of preferred codons ending with G or C (Duret and Mouchiroud, 1999). However, the GC-content at third coding positions (GC3) is also correlated to the GC-content of the surrounding non-coding regions (Kliman and Hey, 1994; Akashi et al., 1998), which suggests the action of gBGC shaping local base compositions. By locally increasing GC-content, gBGC mechanically restricts the number of used codons and reduces the measured ENc independently of selection for translational efficiency. The measured ENc is thus biased by gBGC and must be corrected with local background nucleotide compositions. In addition, variation in GC-content also impacts measures of gene expression. With the advent of high-throughput sequencing technologies, it is now a standard practice to approximate gene expression levels by counting the number of reads mapping a target in ChIP-seq or RNA-seq analysis. However, sequencing biases artificially over-represent genomic regions with intermediate levels of GC-content (50%), which in turn bias the estimates of gene expression levels (Chouvarine et al., 2016). Testing selection for translational efficiency by measuring the correlation between ENc and gene expression levels therefore requires the use of both GC-corrected ENc and GC-corrected expression levels. ENc estimates can be corrected by GC-content of neighborhood regions (Novembre, 2002), while GC-corrected expression levels can be obtained by applying local LOESS regression (Miller et al., 2011; Benjamini and Speed, 2012; Chandrananda et al., 2014) or quantile normalization-methods (Risso et al., 2011), i.e., by normalizing the raw number of mapped reads by the local GC-content.

The ongoing surge of transcriptomic data will permit measurement of GC-content heterogeneity, preferred codons usage and expression levels across a large number of loci and species. This type of large-scale analysis could open the door to a better understanding of the relationship linking effective population sizes (Ne) and codon usage. As theoretically predicted (Bulmer, 1991), selection on synonymous codons might be stronger in species with large Ne. While the Ne-hypothesis to explain variation in selection on codon usage remains untested by empirical studies, a descriptive study of the Ne-effect on variation in gBGC will be necessary to avoid entangling the two effects. Future projects aiming to test these hypotheses are expected to be strongly biased if GC-content biases are naively neglected regarding estimates of gene expression levels or codon usage.

Conclusion

GC-content is associated to multiple biases of different nature (Figure 1). Whether through technological reasons (sequencing technologies biases), biological reasons (GC-biased gene conversion) or methodological reasons (models of sequence evolution limitations), all these biases affect the results of downstream analyses. With the surge of genomic data from various non-model species, comparative genomics have the opportunity to solve many unresolved questions in evolution. However, one should be aware of the methodological challenges associated to the GC-content heterogeneity inherent to large scale studies, whether it be for a large number of species or loci.

Author Contributions

JR had the idea of the project. JR and CR wrote the article.

Funding

This work was supported by a Federation of European Biochemical Societies (FEBS) long-term fellowship to JR.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

Akashi, H. (1995). Inferring weak selection from patterns of polymorphism and divergence at “silent” sites in Drosophila DNA. Genetics 139, 1067–1076.

Akashi, H., Kliman, R. M., and Eyre-Walker, A. (1998). Mutation pressure, natural selection, and the evolution of base composition in Drosophila. Genetica 10, 49–60. doi: 10.1023/A:1017078607465

Akashi, H., and Schaeffer, S. W. (1997). Natural selection and the frequency distributions of “silent” DNA polymorphism in Drosophila. Genetics 146, 295–307.

Arbeithuber, B., Betancourt, A. J., Ebner, T., and Tiemann-Boege, I. (2015). Crossovers are associated with mutation and biased gene conversion at recombination hotspots. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 112, 2109–2114. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1416622112

Beaumont, M. A., Zhang, W., and Balding, D. J. (2002). Approximate Bayesian computation in population genetics. Genetics 162, 2025–2035.

Benjamini, Y., and Speed, T. P. (2012). Summarizing and correcting the GC content bias in high-throughput sequencing. Nucleic Acids Res. 40:e72. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks001

Berglund, J., Pollard, K. S., and Webster, M. T. (2009). Hotspots of biased nucleotide substitutions in human genes. PLoS Biol. 7:e26. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000026

Bernardi, G., Olofsson, B., Filipski, J., Zerial, M., Salinas, J., Cuny, G., et al. (1985). The mosaic genome of warm-blooded vertebrates. Science 228, 953–958. doi: 10.1126/science.4001930

Betancur-R, R., Li, C., Munroe, T. A., Ballesteros, J. A., and Ortí, G. (2013). Addressing gene tree discordance and non-stationarity to resolve a multi-locus phylogeny of the flatfishes (Teleostei: Pleuronectiformes). Syst. Biol. 62, 763–785. doi: 10.1093/sysbio/syt039

Bierne, N., Welch, J., Loire, E., Bonhomme, F., and David, P. (2011). The coupling hypothesis: why genome scans may fail to map local adaptation genes. Mol. Ecol. 20, 2044–2072. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2011.05080.x

Blanquart, S., and Lartillot, N. (2006). A Bayesian compound stochastic process for modeling nonstationary and nonhomogeneous sequence evolution. Mol. Biol. Evol. 23, 2058–2071. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msl091

Bolívar, P., Mugal, C. F., Nater, A., and Ellegren, H. (2015). Recombination rate variation modulates gene sequence evolution mainly via GC-biased gene conversion, not Hill–Robertson interference, in an avian system. Mol. Biol. Evol. 33, 216–227. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msv214

Boussau, B., and Gouy, M. (2006). Efficient likelihood computations with nonreversible models of evolution. Syst. Biol. 55, 756–768. doi: 10.1080/10635150600975218

Bulmer, M. (1991). The selection-mutation-drift theory of synonymous codon usage. Genetics 129, 897–907.

Capra, J. A., Hubisz, M. J., Kostka, D., Pollard, K. S., and Siepel, A. (2013). A model-based analysis of GC-biased gene conversion in the human and chimpanzee genomes. PLoS Genet. 9:e1003684. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1003684

Chandrananda, D., Thorne, N. P., Ganesamoorthy, D., Bruno, D. L., Benjamini, Y., Speed, T. P., et al. (2014). Investigating and correcting plasma DNA sequencing coverage bias to enhance aneuploidy discovery. PLoS ONE 9:e86993. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0086993

Charlesworth, B., Morgan, M. T., and Charlesworth, D. (1993). The effect of deleterious mutations on neutral molecular variation. Genetics 134, 1289–1303.

Chouvarine, P., Wiehlmann, L., Losada, P. M., DeLuca, D. S., and Tümmler, B. (2016). Filtration and normalization of sequencing read data in whole-metagenome shotgun samples. PLoS ONE 11:e0165015. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0165015

Clark, A. G. (1997). Neutral behavior of shared polymorphism. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 94, 7730–7734. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.15.7730

Collins, T. M., Fedrigo, O., and Naylor, G. J. P. (2005). Choosing the best genes for the job: the case for stationary genes in genome-scale phylogenetics. Syst. Biol. 54, 493–500. doi: 10.1080/10635150590947339

Comeron, J. M. (2004). Selective and mutational patterns associated with gene expression in humans: influences on synonymous composition and intron presence. Genetics 167, 1293–1304. doi: 10.1534/genetics.104.026351

Coop, G., and Myers, S. R. (2007). Live hot, die young: transmission distortion in recombination hotspots. PLoS Genet. 3:e35. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.0030035

Csilléry, K., Blum, M. G. B., Gaggiotti, O. E., and François, O. (2010a). Approximate Bayesian Computation (ABC) in practice. Trends Ecol. Evol. 25, 410–418. doi: 10.1016/j.tree.2010.04.001

Csilléry, K., Blum, M. G. B., Gaggiotti, O. E., and François, O. (2010b). Invalid arguments against ABC: reply to A.R. Templeton. Trends Ecol. Evol. 25, 490–491. doi: 10.1016/j.tree.2010.06.011

Csilléry, K., François, O., and Blum, M. G. B. (2012). abc: an R package for approximate Bayesian computation (ABC). Methods Ecol. Evol. 3, 475–479. doi: 10.1111/j.2041-210X.2011.00179.x

Degnan, J. H., and Rosenberg, N. A. (2009). Gene tree discordance, phylogenetic inference and the multispecies coalescent. Trends Ecol. Evol. 24, 332–340. doi: 10.1016/j.tree.2009.01.009

Delsuc, F. (2003). Comment on “Hexapod origins: monophyletic or paraphyletic?” Science 301, 1490–1491. doi: 10.1126/science.1086558

Duret, L., and Arndt, P. F. (2008). The impact of recombination on nucleotide substitutions in the human genome. PLoS Genet. 4:e1000071. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000071

Duret, L., and Galtier, N. (2009). Biased gene conversion and the evolution of mammalian genomic landscapes. Annu. Rev. Genomics Hum. Genet. 10, 285–311. doi: 10.1146/annurev-genom-082908-150001

Duret, L., and Mouchiroud, D. (1999). Expression pattern and, surprisingly, gene length shape codon usage in Caenorhabditis, Drosophila, and Arabidopsis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 96, 4482–4487. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.8.4482

Duret, L., Semon, M., Piganeau, G., Mouchiroud, D., and Galtier, N. (2002). Vanishing GC-rich isochores in mammalian genomes. Genetics 162, 1837–1847.

Dutheil, J., and Boussau, B. (2008). Non-homogeneous models of sequence evolution in the Bio++ suite of libraries and programs. BMC Evol. Biol. 8:255. doi: 10.1186/1471-2148-8-255

Ellegren, H. (2014). Genome sequencing and population genomics in non-model organisms. Trends Ecol. Evol. 29, 51–63. doi: 10.1016/j.tree.2013.09.008

Eyre-Walker, A. (1993). Recombination and mammalian genome evolution. Proc. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 252, 237–243. doi: 10.1098/rspb.1993.0071

Eyre-Walker, A., and Hurst, L. D. (2001). The evolution of isochores. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2, 549–555. doi: 10.1038/35080577

Felsenstein, J. (1978). Cases in which parsimony or compatibility methods will be positively misleading. Syst. Zool. 27, 401–410. doi: 10.2307/2412923

Figuet, E., Ballenghien, M., Romiguier, J., and Galtier, N. (2014). Biased gene conversion and GC-content evolution in the coding sequences of reptiles and vertebrates. Genome Biol. Evol. 7, 240–250. doi: 10.1093/gbe/evu277

Foster, P. (2004). Modeling compositional heterogeneity. Syst. Biol. 53, 485–495. doi: 10.1080/10635150490445779

Galtier, N., and Duret, L. (2007). Adaptation or biased gene conversion? Extending the null hypothesis of molecular evolution. Trends Genet. 23, 273–277. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2007.03.011

Galtier, N., Duret, L., Glémin, S., and Ranwez, V. (2009). GC-biased gene conversion promotes the fixation of deleterious amino acid changes in primates. Trends Genet. 25, 1–5. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2008.10.011

Galtier, N., and Gouy, M. (1998). Inferring pattern and process: maximum-likelihood implementation of a nonhomogeneous model of DNA sequence evolution for phylogenetic analysis. Mol. Biol. Evol. 15, 871–879. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a025991

Galtier, N., Piganeau, G., Mouchiroud, D., and Duret, L. (2001). GC-content evolution in mammalian genomes: the biased gene conversion hypothesis. Genetics 159, 907–911. doi: 10.1038/35091126

Gowri-Shankar, V., and Rattray, M. (2007). A reversible jump method for Bayesian phylogenetic inference with a nonhomogeneous substitution model. Mol. Biol. Evol. 24, 1286–1299. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msm046

Haller, B. C., and Messer, P. W. (2017). SLiM 2: flexible, interactive forward genetic simulations. Mol. Biol. Evol. 34, 230–240. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msw211

Hobolth, A., Dutheil, J. Y., Hawks, J., Schierup, M. H., and Mailund, T. (2011). Incomplete lineage sorting patterns among human, chimpanzee, and orangutan suggest recent orangutan speciation and widespread selection. Genome Res. 21, 349–356. doi: 10.1101/gr.114751.110

International Human Genome Sequencing Consortium (2001). Initial sequencing and analysis of the human genome. Nature 412, 860–921. doi: 10.1038/35057062

Kent, C. F., Minaei, S., Harpur, B. A., and Zayed, A. (2012). Recombination is associated with the evolution of genome structure and worker behavior in honey bees. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 109, 18012–18017. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1208094109

Kliman, R. M., and Hey, J. (1994). The effects of mutation and natural selection on codon bias in the genes of Drosophila. Genetics 137, 1049–1056.

Kostka, D., Hubisz, M. J., Siepel, A., and Pollard, K. S. (2012). The role of GC-biased gene conversion in shaping the fastest evolving regions of the human genome. Mol. Biol. Evol. 29, 1047–1057. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msr279

Lachance, J., and Tishkoff, S. A. (2014). Biased gene conversion skews allele frequencies in human populations, increasing the disease burden of recessive alleles. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 95, 408–420. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2014.09.008

Lartillot, N. (2013). Interaction between selection and biased gene conversion in mammalian protein-coding sequence evolution revealed by a phylogenetic covariance analysis. Mol. Biol. Evol. 30, 356–368. doi: 10.1093/molbev/mss231

Lesecque, Y., Glémin, S., Lartillot, N., Mouchiroud, D., and Duret, L. (2014). The red queen model of recombination hotspots evolution in the light of archaic and modern human genomes. PLoS Genet. 10:e1004790. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1004790

Li, C., and Ortí, G. (2007). Molecular phylogeny of Clupeiformes (Actinopterygii) inferred from nuclear and mitochondrial DNA sequences. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 44, 386–398. doi: 10.1016/j.ympev.2006.10.030

Liu, L., Yu, L., Pearl, D. K., and Edwards, S. V. (2009). Estimating species phylogenies using coalescence times among sequences. Syst. Biol. 58, 468–477. doi: 10.1093/sysbio/syp031

Mallick, S., Gnerre, S., Muller, P., and Reich, D. (2009). The difficulty of avoiding false positives in genome scans for natural selection. Genome Res. 19, 922–933. doi: 10.1101/gr.086512.108

McCormack, J. E., Faircloth, B. C., Crawford, N. G., Gowaty, P. A., Brumfield, R. T., and Glenn, T. C. (2012). Ultraconserved elements are novel phylogenomic markers that resolve placental mammal phylogeny when combined with species-tree analysis. Genome Res. 22, 746–754. doi: 10.1101/gr.125864.111

Miller, C. A., Hampton, O., Coarfa, C., and Milosavljevic, A. (2011). ReadDepth: a parallel R package for detecting copy number alterations from short sequencing reads. PLoS ONE 6:e16327. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0016327

Montoya-Burgos, J. I., Boursot, P., and Galtier, N. (2003). Recombination explains isochores in mammalian genomes. Trends Genet. 19, 128–130. doi: 10.1016/S0168-9525(03)00021-0

Moriyama, E. N., and Powell, J. R. (1997). Codon usage bias and tRNA abundance in Drosophila. J. Mol. Evol. 45, 514–523. doi: 10.1007/PL00006256

Mugal, C. F., Weber, C. C., and Ellegren, H. (2015). GC-biased gene conversion links the recombination landscape and demography to genomic base composition: GC-biased gene conversion drives genomic base composition across a wide range of species. Bioessays 37, 1317–1326. doi: 10.1002/bies.201500058

Nabholz, B., Künstner, A., Wang, R., Jarvis, E. D., and Ellegren, H. (2011). Dynamic evolution of base composition: causes and consequences in avian phylogenomics. Mol. Biol. Evol. 28, 2197–2210. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msr047

Nagylaki, T. (1983). Evolution of a finite population under gene conversion. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 80, 6278–6281. doi: 10.1073/pnas.80.20.6278

Necşulea, A., Popa, A., Cooper, D. N., Stenson, P. D., Mouchiroud, D., Gautier, C., et al. (2011). Meiotic recombination favors the spreading of deleterious mutations in human populations. Hum. Mutat. 32, 198–206. doi: 10.1002/humu.21407

Novembre, J. A. (2002). Accounting for background nucleotide composition when measuring codon usage bias. Mol. Biol. Evol. 19, 1390–1394. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a004201

Pagani, I., Liolios, K., Jansson, J., Chen, I.-M. A., Smirnova, T., Nosrat, B., et al. (2011). The Genomes OnLine Database (GOLD) v.4: status of genomic and metagenomic projects and their associated metadata. Nucleic Acids Res. 40, D571–D579. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr1100

Pavlidis, P., Jensen, J. D., Stephan, W., and Stamatakis, A. (2012). A critical assessment of storytelling: gene ontology categories and the importance of validating genomic scans. Mol. Biol. Evol. 29, 3237–3248. doi: 10.1093/molbev/mss136

Philippe, H., Brinkmann, H., Lavrov, D. V., Littlewood, D. T. J., Manuel, M., Wörheide, G., et al. (2011). Resolving difficult phylogenetic questions: why more sequences are not enough. PLoS Biol. 9:e1000602. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000602

Philippe, H., Zhou, Y., Brinkmann, H., Rodrigue, N., and Delsuc, F. (2005). Heterotachy and long-branch attraction in phylogenetics. BMC Evol. Biol. 5:50. doi: 10.1186/1471-2148-5-50

Phillips, M. J., Delsuc, F., and Penny, D. (2004). Genome-scale phylogeny and the detection of systematic biases. Mol. Biol. Evol. 21, 1455–1458. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msh137

Plotkin, J. B., Robins, H., and Levine, A. J. (2004). Tissue-specific codon usage and the expression of human genes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 101, 12588–12591. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0404957101

Pollard, K. S., Salama, S. R., Lambert, N., Lambot, M.-A., Coppens, S., Pedersen, J. S., et al. (2006). An RNA gene expressed during cortical development evolved rapidly in humans. Nature 443, 167–172. doi: 10.1038/nature05113

Pudlo, P., Marin, J.-M., Estoup, A., Cornuet, J.-M., Gautier, M., and Robert, C. P. (2016). Reliable ABC model choice via random forests. Bioinformatics 32, 859–866. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btv684

Ratnakumar, A., Mousset, S., Glémin, S., Berglund, J., Galtier, N., Duret, L., et al. (2010). Detecting positive selection within genomes: the problem of biased gene conversion. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 365, 2571–2580. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2010.0007

Risso, D., Schwartz, K., Sherlock, G., and Dudoit, S. (2011). GC-content normalization for RNA-Seq data. BMC Bioinformatics 12:480. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-12-480

Rodríguez-Ezpeleta, N., Brinkmann, H., Roure, B., Lartillot, N., Lang, B. F., and Philippe, H. (2007). Detecting and overcoming systematic errors in genome-scale phylogenies. Syst. Biol. 56, 389–399. doi: 10.1080/10635150701397643

Romiguier, J., Cameron, S. A., Woodard, S. H., Fischman, B. J., Keller, L., and Praz, C. J. (2016). Phylogenomics controlling for base compositional bias reveals a single origin of eusociality in corbiculate bees. Mol. Biol. Evol. 33, 670–678. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msv258

Romiguier, J., Ranwez, V., Delsuc, F., Galtier, N., and Douzery, E. J. P. (2013a). Less is more in mammalian phylogenomics: AT-rich genes minimize tree conflicts and unravel the root of placental mammals. Mol. Biol. Evol. 30, 2134–2144. doi: 10.1093/molbev/mst116

Romiguier, J., Ranwez, V., Douzery, E. J. P., and Galtier, N. (2010). Contrasting GC-content dynamics across 33 mammalian genomes: relationship with life-history traits and chromosome sizes. Genome Res. 20, 1001–1009. doi: 10.1101/gr.104372.109

Romiguier, J., Ranwez, V., Douzery, E. J. P., and Galtier, N. (2013b). Genomic evidence for large, long-lived ancestors to placental mammals. Mol. Biol. Evol. 30, 5–13. doi: 10.1093/molbev/mss211

Roux, C., Fraïsse, C., Romiguier, J., Anciaux, Y., Galtier, N., and Bierne, N. (2016). Shedding light on the grey zone of speciation along a continuum of genomic divergence. PLoS Biol. 14:e2000234. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.2000234

Roux, C., Pauwels, M., Ruggiero, M.-V., Charlesworth, D., Castric, V., and Vekemans, X. (2012). Recent and ancient Signature of balancing selection around the S-Locus in Arabidopsis halleri and A. lyrata. Mol. Biol. Evol. 30, 435–447. doi: 10.1093/molbev/mss246

Sheffield, N. C., Song, H., Cameron, S. L., and Whiting, M. F. (2009). Nonstationary evolution and compositional heterogeneity in beetle mitochondrial phylogenomics. Syst. Biol. 58, 381–394. doi: 10.1093/sysbio/syp037

Smith, J. M., and Haigh, J. (1974). The hitch-hiking effect of a favourable gene. Genet. Res. 23, 23–35. doi: 10.1017/S0016672300014634

Spencer, C. C. A. (2006). Human polymorphism around recombination hotspots. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 34, 535–536. doi: 10.1042/BST0340535

Teeling, E. C., Scally, M., Kao, D. J., Romagnoli, M. L., Springer, M. S., and Stanhope, M. J. (2000). Molecular evidence regarding the origin of echolocation and flight in bats. Nature 403, 188–192. doi: 10.1038/35003188

Urrutia, A. O. (2003). The signature of selection mediated by expression on human genes. Genome Res. 13, 2260–2264. doi: 10.1101/gr.641103

Weber, C. C., Boussau, B., Romiguier, J., Jarvis, E. D., and Ellegren, H. (2014). Evidence for GC-biased gene conversion as a driver of between-lineage differences in avian base composition. Genome Biol. 15:549. doi: 10.1186/s13059-014-0549-1

Williamson, S. H., Hernandez, R., Fledel-Alon, A., Zhu, L., Nielsen, R., and Bustamante, C. D. (2005). Simultaneous inference of selection and population growth from patterns of variation in the human genome. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 102, 7882–7887. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0502300102

Keywords: GC-content, positive selection, biased gene conversion, codon usage bias, phylogeny, methodological biases

Citation: Romiguier J and Roux C (2017) Analytical Biases Associated with GC-Content in Molecular Evolution. Front. Genet. 8:16. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2017.00016

Received: 01 December 2016; Accepted: 06 February 2017;

Published: 15 February 2017.

Edited by:

Scott V. Edwards, Harvard University, USAReviewed by:

Jacob A. Tennessen, Oregon State University, USAChris Organ, Montana State University, USA

Copyright © 2017 Romiguier and Roux. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) or licensor are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Jonathan Romiguier, jonathan.romiguier@gmail.com

Jonathan Romiguier

Jonathan Romiguier Camille Roux

Camille Roux