More Information

Submitted: October 12, 2022 | Approved: October 25, 2022 | Published: October 26, 2022

How to cite this article: Rigby K. The central role of desire in mediating bullying behavior in schools. Arch Psychiatr Ment Health. 2022; 6: 036-039.

DOI: 10.29328/journal.apmh.1001042

Copyright License: © 2022 Rigby K. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

The central role of desire in mediating bullying behavior in schools

Kenneth Rigby*

University of South Australia, Australia

*Address for Correspondence: Kenneth Rigby, University of South Australia, Australia, Email: Kenneth.Rigby@unisa.edu.au

Numerous studies of bullying in schools have identified aspects of the environment (E) and aspects of the person (P) as contributing to the prevalence of bullying in schools. It is proposed that the concept of desire can play a central role in explaining how bullying in schools arises and how it can be effectively addressed by schools by promoting social and emotional learning, mindfulness, and problem-solving techniques such as the Method of Shared Concern. The article identifies a need for further research to confirm the hypothesized relationships and assess the utility of the concept of desire as a variable in research and the practice of bullying prevention in schools.

As is now well known, bullying in schools can have serious and enduring effects on the mental health of children [1]. Moreover, there is little or no evidence of the effectiveness of interventions to lessen its prevalence in many countries [2]. It is perhaps time to consider a new approach to understanding bullying and the implications it may have for addressing bullying at school.

It is generally agreed that bullying behavior involves the deliberate use of negative actions, repeated over time, by a person or group that is more powerful than the one being targeted. It is multiplied determined, with some factors associated with the person (P) of the perpetrator such as genetic nature [3] and also relatively stable personality traits, such as low levels of empathy [4]; low tolerance to frustration [5]; and low agreeableness [6]. One may also add gender and age; males and students in early adolescence are generally more likely to engage in bullying, especially physical bullying [7].

Complementing and interacting with such personal factors are some environmental (E) factors identified as contributory causes. These include exposure to a cold, authoritarian style of parenting [8,9]; troublesome neighborhoods, and a non-supportive school ethos [10]. It is proposed that personal and environmental factors may operate interactively and indirectly through the agency of desire in bringing about bullying behavior [11].

Desire has been conceived as a disposition in the organism to act to bring about a specific outcome, notably by Anscombe [12]. According to Strawson [13], the desire for an object or goal includes an anticipated enjoyment of what is desired. In some cases, in bullying the enjoyment may lie in the sadistic pleasure it brings; in other cases, it may lie in the social status that is thereby achieved. Scanlon [14], has noted further that in desire there is a tendency for one’s attention to be drawn insistently toward the means for its realization. This leads to a variety of methods being employed repeatedly over time to hurt or subjugate a victim, including physical assault, verbal abuse, exclusion, and cyber harassment: in short to bully someone.

Measures of this hypothesized desire have drawn upon the concept of sadism, that is, the desire and intention to hurt others, either verbally or physically, simply for the enjoyment of the act (Spain, 2019). Various studies have in fact found significant positive correlations between reliable measures of sadism and reported bullying behavior among schoolchildren [15]. However, not all researchers have accepted that bullying necessarily entails the desire to hurt; arguably bullying can be directed toward achieving higher status, rather than the enjoyment of another’s pain [16]. Examining the role of desire in mediating bullying behavior requires a broader definition and a corresponding measure.

A concept that in some ways resembles ‘desire’ is ‘intention’; both concepts refer to a state of mind that commonly precedes action. Not surprisingly, a high proportion of individuals have been reported as fulfilling their stated intentions [17]. However, ‘desire’ has wider connotations. It does not imply a commitment to action to the same degree as ‘intention.’ One may reasonably expect action to be preceded by a relevant desire, but to be far less certain that a given desire will in fact be expressed, given the likelihood of possible competing desires, as well as varying circumstances. A further aspect of the desire to bully someone is its apparent insatiability. The desire is not to destroy the target once and for all, but to keep resuming the action to gain further satisfaction.

Whether a desire to bully results in actual bullying behavior would appear to depend in part, on the intensity of the desire. The desire may be relatively weak and ephemeral, in which case it may dissipate and no aggression may result. Alternatively, with a more intense and sustained desire, aggression may be expressed through fighting or quarreling with someone. However, given a strong and persistent desire to hurt or subjugate someone, together with the accessibility of someone who is perceived as less powerful, bullying can be a chosen option, especially if a potential bully is morally disengaged (Thornberg, & Jungert (2014) and the victim unsupported, for example, when bystanders ignore the bullying or, in some cases, encourage it (Hawkins, Pepler & Craig 2001).

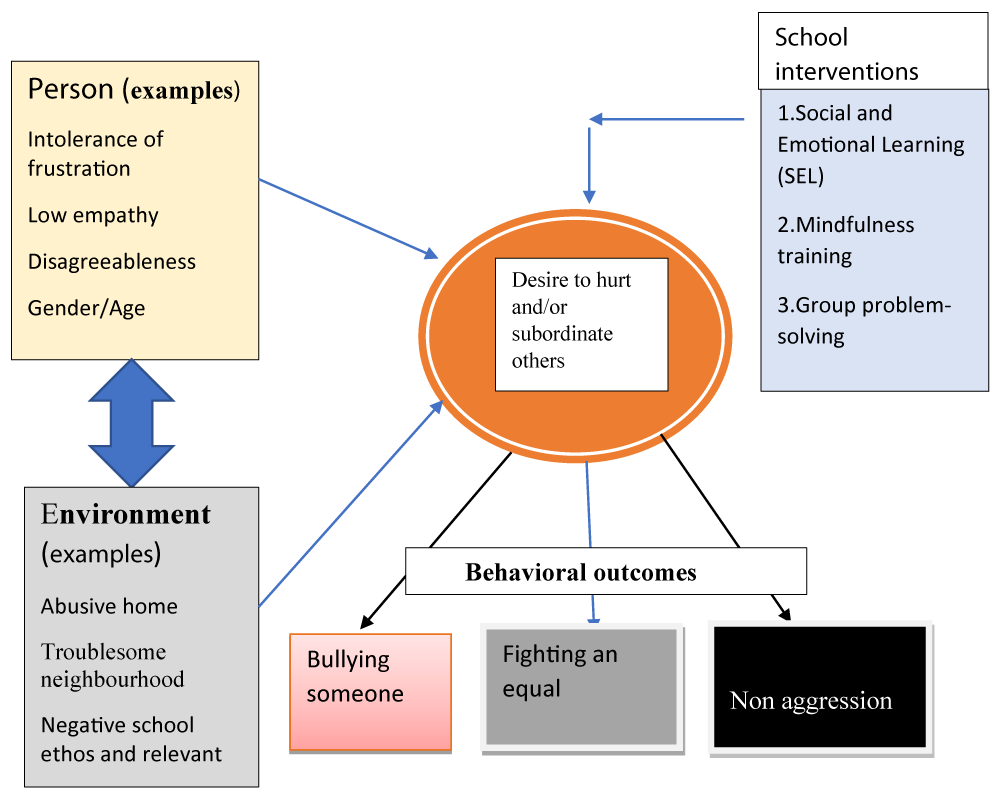

The proposed central role of the desire to hurt and/or subordinate others is described in Figure 1, modified from a more extensive one given in Rigby [18]. P and E in interaction are shown as inducing this desire, which may be expressed as bullying as quarreling or fighting or not expressed at all. Interventions by schools to prevent bullying are seen as operating by reducing the desire to hurt and/or subordinate another person.

Figure 1: Relationships and potential influences involving Person and Environ-mental factors and school interventions in determining the desire to hurt and/or subjugate others and possible behavioral outcomes.

Implications for addressing bullying

Recognition of the role of desire in explaining bullying may lead schools to take specific actions directed primarily towards reducing such desire among students. Three strategies or methods may be identified.

1. Currently, the most widely recognized proactive form is through the work with students in the classroom to develop social and emotional learning. Social and emotional learning (SEL) is seen as the process through which children acquire the knowledge, attitudes, and skills necessary to understand and manage emotions, set and achieve positive goals, and feel and show empathy for others. Establish and maintain positive relationships, and make responsible decisions [19]. SEL is integrated into the school curriculum with the aim of promoting the development of positive qualities such as the ability to manage emotions, experience empathy towards others and form constructive relationships. A meta-analysis of program outcomes based on 89 studies has reported mixed results [20]. In some studies, significant reductions in problem behaviors such as bullying were reported, but not in all. Much appears to depend on how such programs are implemented and the social skills and commitment of teachers.

2. The second method of an intervention lies in the teaching of mindfulness. According to the American Psychological Association [21], mindfulness is a moment-to-moment aware-ness of one’s experience without judgment. If it is taught effectively, one might expect it to reduce the desire to hurt or subjugate others. In recent years interest in developing this way of thinking has risen rapidly and highly promising reports have become available, based on empirical studies on the link between the teaching of mindfulness and bullying behavior among school children [22,23].

3. A third way in which the desire to bully may be countered is through engaging students in activities that are incompatible with bullying others, for example in helping to resolve interpersonal problems positively. Some intervention methods seek to involve students, including the perpetrators of bullying, in meetings at which they are given the opportunity to suggest ways they can contribute to a solution. Examples of such methods include Restorative Practices, the Support Group Method and the Method of Shared Concern [18,24]. The rationale for such methods is that they enable children who have bullied someone to decide, individually and collectively, how they will act and ‘own’ their restorative and caring actions (rather than simply doing what they are told), thereby accomplishing a vital and sustainable attitude or state of desire that is incompatible with bullying someone.

It should be recognized that the skills needed by teacher practitioners to apply these methods effectively may not be available in some schools, and both training and aptitude may not always be adequate. Further, controversy exists over whether such ‘therapeutic’ methods are appropriate in a pedagogic institution [25]. As traditional ways of educating young people, and the social and psychological harm of bullying become more fully recognized, their relevance and use may become more widespread and the proposed interventions more likely to be employed.

Further research is clearly needed to examine the assumptions and hypotheses underlying the theoretical relationships proposed in this article. This should include the development of a psychometrically acceptable measure of the desire to hurt and/or subjugate another person. There are measures available for use in schools that contain items considered relevant to sadism, for example, see Buckels [26]; but, as previously argued, bullying may involve non-sadistic motives, such as in seeking to improve the perpetrator’s social status. Hence, there is a need to produce a scale that encompasses a wider range of items, as in a desire to dominate without necessarily seeking to hurt. Whether such a scale could be devised in which a set of items were loaded on a general factor would need to be determined.

Hypothesized mediation effects related to the desire to hurt and/or subordinate others (D) may be assessed using multiple regression analyses leading to path analyses [27] showing direct and/or indirect linkages with the dependent variable, a reliable measure of bullying prevalence (BP): see Shaw, et al. [28], as well as other independent variables These would include measures of D, and also Environmental (E) and Person factors (P) identified in the research literature as correlated with BP. To increase the generalisability of the findings, multilevel, modeling could also be employed, drawing on data from a variety of schools catering to students varying in gender and age, as in a study reported by Merrin, Espelage & Jun Sung Hong [29]. Finally, a pre-test, post-test control group design [30-32] could be employed to assess the effectiveness of the three suggested intervention methods and also whether changes over time in BP correlated with reductions in D for individual students, again controlling for gender and age.

- Armitage R. Bullying in children: impact on child health. BMJ Paediatr Open. 2021 Mar 11;5(1):e000939. doi: 10.1136/bmjpo-2020-000939. PMID: 33782656; PMCID: PMC7957129.

- UNESCO (2019) School violence and bullying: global status and trends, drivers and consequences. Paris: UNESCO.

- Ball HA, Arseneault L, Taylor A, Maughan B, Caspi A, Moffitt TE. Genetic and environmental influences on victims, bullies and bully-victims in childhood. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2008 Jan;49(1):104-12. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2007.01821.x. PMID: 18181884.

- Jolliffe D, Farrington D. Examining the relationship between low empathy and bullying. Aggressive Behavior. 2006; 32:540-550.

- Potard C, Pochon R, Henry A, Combes C, Kubiszewski V, Roy A. Relationships between school bullying and frustration intolerance beliefs in adolescence: A gender-specific analysis. Journal of Rational-Emotive & Cognitive-Behavior Therapy. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10942-021-00402-6

- Astor RA, Benbenisthty R.Bullying School Violence and Climate in Evolving Contexts: Culture, Organization and Time. Oxford: Oxford University Press. 2018.

- Bartlett CP, Anderson CA. Direct and indirect relations between the Big 5 personality traits and aggressive and violent behavior. Personality and Individual differences. 2012; 52:8; 870-875.

- Bowes L, Arseneault L, Maughan B, Taylor A, Caspi A, Moffitt TE. School, neighborhood, and family factors are associated with children's bullying involvement: a nationally representative longitudinal study. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2009 May;48(5):545-553. doi: 10.1097/CHI.0b013e31819cb017. PMID: 19325496; PMCID: PMC4231780.

- Connell NM, Morris RG, Piquero AR. Predicting Bullying: Exploring the Contributions of Childhood Negative Life Experiences in Predicting Adolescent Bullying Behavior. Int J Offender Ther Comp Criminol. 2016 Jul;60(9):1082-96. doi: 10.1177/0306624X15573760. Epub 2015 Mar 10. PMID: 25759430.

- Modin B, Låftman SB, Östberg V. Teacher Rated School Ethos and Student Reported Bullying-A Multilevel Study of Upper Secondary Schools in Stockholm, Sweden. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2017 Dec 13;14(12):1565. doi: 10.3390/ijerph14121565. PMID: 29236039; PMCID: PMC5750983.

- Rigby K. (2012) Bullying interventions in schools: Six basic approaches. Boston/Wiley (American edition).

- Anscombe E. Intention (2nd ed). Cambridge: Harvard University Press. 2000.

- Strawson G. Mental reality. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. 1994.

- Scanlon T. What we owe to each other. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. 1998.

- Geel M, Goemans A, Toprak F, Vedder P. Which personality traits are related to traditional bullying and cyberbullying? A study with the big five, dark triad and sadism. Personality and Individual Differences. 2017; 106(1):231-235

- Pellegrini D, Long JD. A longitudinal study of bullying, dominance, and victimization during the transition from primary school through secondary school. British Journal of Developmental Psychology. 2002; 20:259-280.

- Ajzen I. The theory of planned behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes. 1991; 50(2):179-211.

- Rigby K, Griffiths C. Addressing cases of bullying through the Method of Shared Concern. School Psychology International 32: 345-357.

- Durlak JA, Weissberg RP, Dymnicki AB, Taylor RD, Schellinger KB. The impact of enhancing students' social and emotional learning: a meta-analysis of school-based universal interventions. Child Dev. 2011 Jan-Feb;82(1):405-32. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2010.01564.x. PMID: 21291449.

- Wigelsworth M, Lendrum A, Oldfield J, Scott A, Ten Bokkel I, Tate K, Emery C. The impact of trial stage, developer involvement and international transferability on universal social and emotional learning programme outcomes: A meta-analysis. Cambridge Journal of Education. 46(3): 347– 376.

- APA org. What Are The Benefits of Mindfulness? 2012. https://www.apa.org/education/ce/mindfulness-benefits.pdf.

- Foody M, Samara M. Considering mindfulness techniques in school-based antibullying programs. Journal of New Approaches in Educational Research. 2018; 7 (1):3-9.

- Liu X, Xiao R, Tang W. The Impact of School-Based Mindfulness Intervention on Bullying Behaviors among Teenagers: Mediating Effect of Self-Control. J Interpers Violence. 2022 Nov;37(21-22):NP20459-NP20481. doi: 10.1177/08862605211052047. Epub 2021 Nov 22. PMID: 34802328.

- Rigby K (2022) Interventions in cases of bullying in schools: a training manual for teachers and counsellors. Melbourne: Hawker-Brownlow.

- Ecclestone K, Hayes D. The Dangerous Rise of Therapeutic Education. London: Routledge. 2009.

- Buckels EE. Multifaceted assessment of sadistic tendencies. In Jonason PK (Ed.). Shining light on the dark side of personality: Measurement properties and theoretical advances. Newburyport MA: Hogrefe. 2022.

- Everitt BS, Dunn G. Applied multivariate data analysis. London: Edward Arnold. 1991.

- Shaw T, Dooley JJ, Cross D, Zubrick SR, Waters S. The Forms of Bullying Scale (FBS): validity and reliability estimates for a measure of bullying victimization and perpetration in adolescence. Psychol Assess. 2013 Dec; 25(4):1045-57. doi: 10.1037/a0032955. Epub 2013 Jun 3. PMID: 23730831.

- Merrin GJ, Espelage DL, Hong JSW. Applying the Social-Ecological Framework to Understand the Associations of Bullying Perpetration among High School Students: A Multilevel Analysis Psychology of Violence. 2018; 8:1; 43-56.

- Campbell DT, Stanley J. Experimental and quasi-experimental designs for research. Chicago, IL: Rand McNally. 1963.

- Farrington D, Ttofi M, Zych I. Protective factors against bullying and cyberbullying: A systematic review of meta-analyses, Aggression and Violent Behavior. 2019; 45:4-19.

- Rigby K. Bullying in Schools: Addressing Desires, Not Only Behaviors. Educational Psychology Review. 2012; 24(2):339-348.