- Department of Neurosurgery, University of Patras, University Hospital of Patras, Achaia, Greece.

- Department of Radiology and Interventional Neuroradiology, University of Patras, University Hospital of Patras, Achaia, Greece.

- Department of Rehabilitation, Rehabilitation Clinic, University of Patras, University Hospital of Patras, Achaia, Greece.

- Department of Neurology and Psychiatry, Neuropsychology Section, University of Patras, University Hospital of Patras, Patras, Achaia, Greece.

- Department of Neurosurgery and Endovascular Neurosurgery, University of Patras, University Hospital of Patras, Patras, Achaia, Greece.

DOI:10.25259/SNI_434_2021

Copyright: © 2021 Surgical Neurology International This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Non Commercial-Share Alike 4.0 License, which allows others to remix, tweak, and build upon the work non-commercially, as long as the author is credited and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms.How to cite this article: Andreas Theofanopoulos1, Petros Zampakis2, Eleftheria Antoniadou3, Dimitrios Papadakos1, Dionysia Fermeli1, Constantine Constantoyannis1, Lambros Messinis4, Vasileios Panagiotopoulos5. Spontaneous thoracolumbar epidural hematoma in an apixaban anticoagulated patient. 07-Jun-2021;12:256

How to cite this URL: Andreas Theofanopoulos1, Petros Zampakis2, Eleftheria Antoniadou3, Dimitrios Papadakos1, Dionysia Fermeli1, Constantine Constantoyannis1, Lambros Messinis4, Vasileios Panagiotopoulos5. Spontaneous thoracolumbar epidural hematoma in an apixaban anticoagulated patient. 07-Jun-2021;12:256. Available from: https://surgicalneurologyint.com/surgicalint-articles/10871/

Abstract

Background: Spontaneous spinal epidural hematomas (SSEHs) are often attributed to anticoagulation. Although they are rare, they may contribute to significant morbidity and mortality.

Case Description: An 83-year-old female with a history of atrial fibrillation on apixaban, presented with 4 days of back pain, progressive lower extremity weakness and urinary retention. When the patient’s MRI showed a dorsal thoracolumbar SSEH, the patient underwent a T10–L3 laminectomy for hematoma evacuation. Within 2 postoperative months, her neurological deficits fully resolved.

Conclusion: Apixaban is associated with SSEH resulting in severe neurological morbidity and even mortality. Prompt MRI imaging followed by emergency surgical decompressive surgery may result in full resolution of neurological deficits.

Keywords: Apixaban, Spontaneous spinal epidural hematoma, SSEH

INTRODUCTION

Spontaneous spinal epidural hematoma (SSEH) is rare (affecting 0.1/100,000 persons/year) and can potentially result in life-altering neurological disability and/or mortality.[

Based on numerous studies, patients on anticoagulation (i.e. warfarin or heparin) are susceptible to developing SSEH.[

Here, an 83-year-old female on apixaban developed a thoracolumbar SSEH (levels T10–L3). Following an urgent MRI, the patient underwent a T10–L3 laminectomy. Within 2 months postoperatively, her preoperative lower extremity paresis and urinary retention fully resolved.

CASE DESCRIPTION

An 83-year-old female with atrial fibrillation on apixaban (Eliquis 2.5 mg bid) presented with back pain (of sudden onset 4 days before). Her symptoms included worsening lower extremity paresis (left 0/5 and right 3/5), an L3 sensory level, and urinary retention.

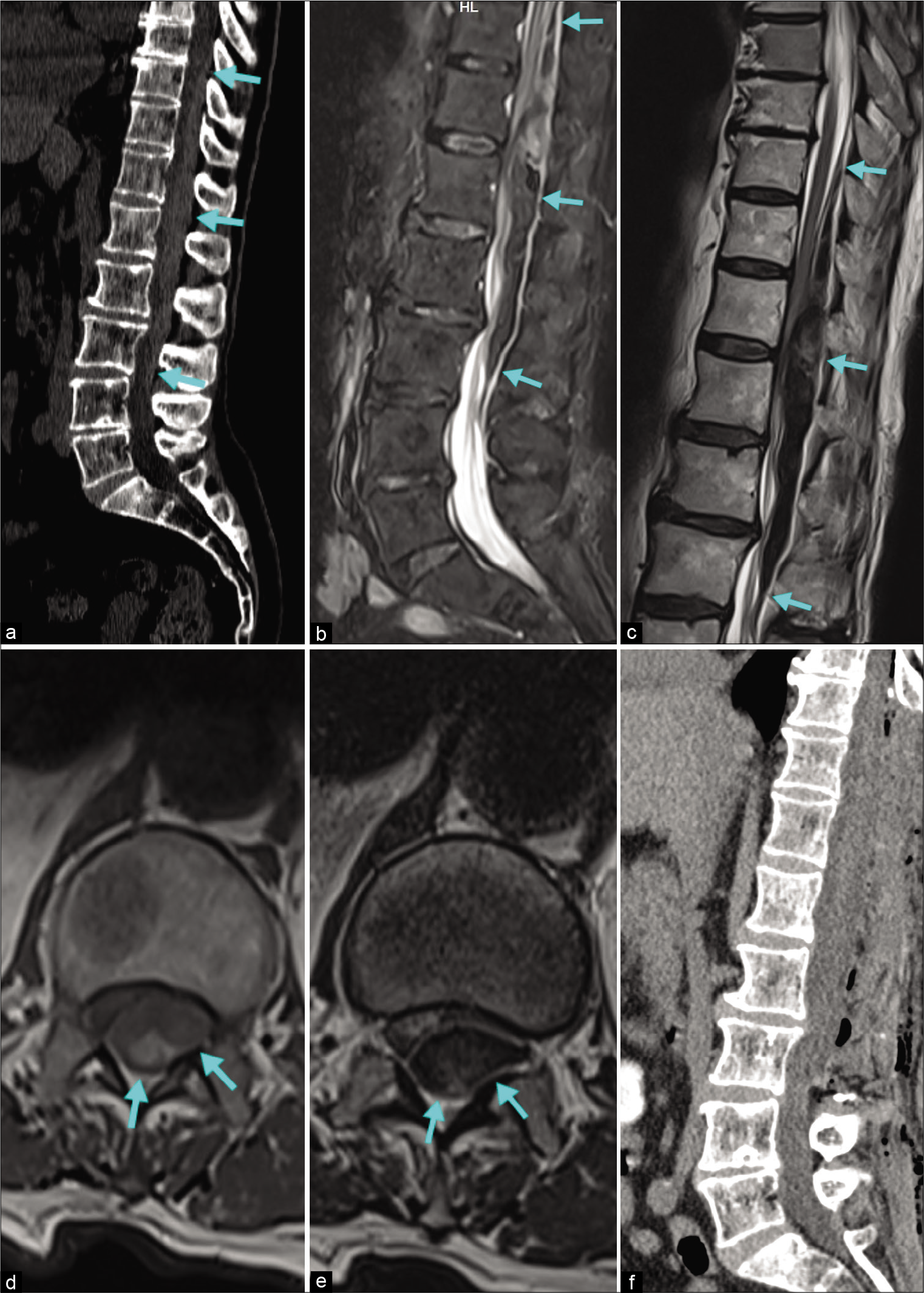

Although all laboratory studies were normal, the noncontrast thoracolumbar CT and MR studies showed a slightly hyperdense, posterior, extradural lesion, extending from T10 to L3 with maximal compression at T12/L1, resulting in significant cord compression [

Figure 1:

(a) Sagittal CT depicts the ventral borders of the epidural hematoma (blue arrows). (b and c) Sagittal STIR (b) and T2W (c) MRI clearly delineating the hematoma in different stages of hemoglobin degradation. (d) Axial T1W MR at the level of maximal compression (T12–L1) showing hematoma occupying almost the entire spinal canal. (e) Axial T2 MRI at the level of maximum compression (T12–L1). (f) Postoperative sagittal CT showing the extent of the laminectomy and complete hematoma evacuation.

Surgery

The patient underwent a T10–L3 laminectomy for evacuation of the SSEH. Immediately postoperatively, the patient was noted to have recovered distal motor strength of 1/5 on the left (ankle plantar flexion and dorsiflexion). Notably, the postoperative CT scan demonstrated complete evacuation of the hematoma, with no postoperative bleeding complications [

Postoperative course

The patient was transferred to a Spinal Rehabilitation Center on the 2nd postoperative day; still largely paraplegic. Bridging anticoagulation with enoxaparin 4000 IU/0.4 ml was initiated on the 3rd postoperative day and was replaced by the patient’s previous apixaban regimen (2.5 mg bid) on the 20th postoperative day. When discharged after 45 days, she was neurologically normal, with only a residual mildly reduced left tibialis anterior muscle strength (4/5).

DISCUSSION

SSEH is rare and carries the risk of significant morbidity and/ or mortality. Patients typically average 63 years of age and typically present with sudden onset back pain, radicular pain, sensorimotor deficits, and sphincter dysfunction reflecting the level of the bleed.[

The most common etiology is spontaneous rupture of the dorsal internal vertebral venous plexus, which is a valveless system susceptible to abrupt pressure changes.[

Most SSEH occur in the cervicothoracic or the thoracolumbar region, with two-thirds extending over 2–5 vertebral segments.[

Diagnostic studies

MRI is the gold standard in assessing SSEH. Hematomas are low signal on T1-weighted sequences in the acute phase, appearing isointense to the cord; T1 signal intensity increases in the subacute phase. On T2-weighted sequences, hematomas are usually hypointense. Although high-resolution CT may also identify these lesions, MRI is clearly the superior diagnostic study.[

Apixaban anticoagulation predisposing to SSEH

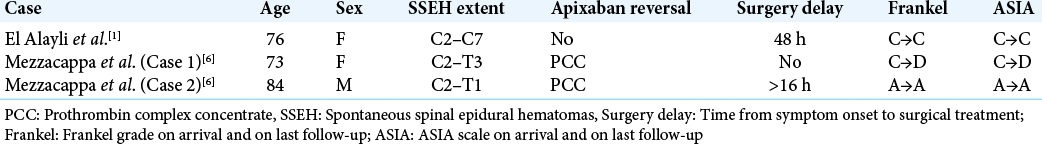

Anticoagulation is a major predisposing factor to SSEH.[

Management of SSEH

Symptomatic SSEH should be managed based on emergency MRI studies; many will require prompt laminectomy.[

CONCLUSION

SSEH, recently associated with apixaban, is a rare medical emergency requiring emergency MRI studies and operative decompression to achieve the best outcomes.

Declaration of patient consent

Patient’s consent not required as patients identity is not disclosed or compromised.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

1. El Alayli A, Neelakandan L, Krayem H. Spontaneous spinal epidural hematoma in a patient on apixaban for nonvalvular atrial fibrillation. Case Rep Hematol. 2020. 2020: 7419050

2. Figueroa J, DeVine JG. Spontaneous spinal epidural hematoma: Literature review. J spine Surg. 2017. 3: 58-63

3. Groen RJ. Non-operative treatment of spontaneous spinal epidural hematomas: A review of the literature and a comparison with operative cases. Acta Neurochir. 2004. 146: 103-10

4. Holtås S, Heiling M, Lönntoft M. Spontaneous spinal epidural hematoma: Findings at MR imaging and clinical correlation. Radiology. 1996. 199: 409-13

5. Kreppel D, Antoniadis G, Seeling W. Spinal hematoma: A literature survey with meta-analysis of 613 patients. Neurosurg Rev. 2003. 26: 1-49

6. Mezzacappa FM, Surdell D, Thorell W. Spontaneous spinal epidural hematoma associated with apixaban therapy: A report of two cases. Cureus. 2020. 12: e11446

7. Wang M, Zhou P, Jiang S. Clinical features, management, and prognostic factors of spontaneous epidural spinal hematoma: Analysis of 24 cases. World Neurosurg. 2017. 102: 360-9

8. Zhong W, Chen H, You C, Li J, Liu Y, Huang S. Spontaneous spinal epidural hematoma. J Clin Neurosci. 2011. 18: 1490-4