Article contents

6 Axioms for Environmental Theatre

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 12 September 2022

Extract

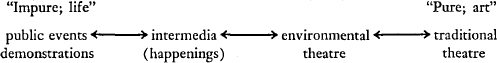

The theatrical event includes audience, performers, text (in most cases), sensory stimuli, architectural enclosure (or lack of it), production equipment, technicians, and house personnel (when used). It ranges from nonmatrixed performance to highly formalized traditional theatre: from chance events and intermedia to “the production of plays.” A continuum of theatrical events blends one form into the next:

It is because I wish to include this entire range in my definition of theatre that traditional distinctions between art and life no longer function at the root of aesthetics. All along the continuum there are overlaps; and within it—say between a traditional production of Hamlet and the March on the Pentagon or Allan Kaprow's Self-Service—there are contradictions.

- Type

- Research Article

- Information

- Copyright

- Copyright © The Drama Review 1968

References

1 Michael Kirby discusses the distinctions between non matrixed and matrixed performances in “The New Theatre,” T30.

2 See this issue of TDR, 160-164.

3 Erving Goffman—a sociologist who looks at behavior from a theatrical point of view—has begun the discussion of expectation-obligation networks in two books: Encounters (Indianapolis: Bobbs-Merrill, 1961) and Behavior in Public Places (Glencoe: The Free Press, 1963).

4 Interview, to be published in full in the Fall, 1968, TDR.

5 “An Interview with John Cage,” TDR, Volume 10, No. 2, pp. 50-51.

6 Encounters, p. 19.

7 Behavior in Public Places, p. 8.

8 A Provo event is described by John Kifner in the New York Times of 25 August 1967. “Dollar bills thrown by a band of hippies fluttered down on the floor of the New York Stock Exchange yesterday, disrupting the normal hectic trading pace. Stockbrokers, clerks, and runners turned and stared at the visitors’ gallery. […] Some clerks ran to pick up the bills. [… ] James Fourrat, who led the demonstration along with Abbie Hoffman, explained in a hushed voice: ‘It's the death of money.’ To forestall any repetition, the officers of the Exchange enclosed the visitors’ gallery in bullet-proof glass.”

9 See T30, pp. 202-211.

10 Great Bear Pamphlet 7 (New York: Something Else Press, 1966). Something Else Press has published many books and pamphlets about intermedia; a great proportion of these includes scenarios and theoretical writings by artists working in intermedia.

11 A complete outline of these techniques can be found in the pamphlet, “Brief Description of the Technical Equipment of the Czechoslovak Pavilion at the Expo 67 World Exhibition” by Jaroslav Fric. One can obtain the pamphlet by writing to Vystavnictvi, N.C., Ovocny trh 19, Prague 1, Czechoslovakia. Fric is chief of research and engineering for the Prague Scenic Institute. Both the Polyvision and the Diapolyecran were developed from ideas of Josef Svoboda. Some of Svoboda's work can be seen in T33, pp. 141-149.

12 An interesting extension of this idea happened during Victims of Duty. There, at several points, the performers operated slide machines and sound sources. At these moments the actors were both technicians and role-playing performers; they modulated the technical environment in which they were performing.

13 The Hevehe Cycle takes from six to twenty years. F. E. Williams, who has written an excellent account of it, believes that the Cycle has been abbreviated since the advent of Western culture in the Papuan Gulf. It seems to me that the Cycle is meant to incorporate the life-span of the Orokolo male. During his life he plays, literally, many roles, each of them relevant ritually, biologically, and socially. See F. E. Williams, The Drama of the Orokolo (London: Oxford University Press, 1940). An extensive, if somewhat haphazard, literature of nonliterate theatre exists. Accounts are rarely organized for use by the theatre theorist or aesthetician; however, I have found ethnographic reading to be of utmost value.

14 The film, Dance and Trance in Bali, is available from the New York University film library.

15 On two occasions spectators came to Victims with the intention of disrupting the performance. That is an act of bad faith, planning to use a mask of spontaneity to conceal anything but spontaneous participation. One of these occasions led to a fist fight between a disrupter and another member of the audience who was a friend of mine. The disrupter was thrown out, and the show continued without most of the audience being aware that anything unusual had happened. The form of the performance permitted such events to be accepted as part of the show. The man who came to disrupt and who was thrown out was a newspaper critic. Such are the small but real pleasures of environmental theatre.

16 For a full account of the Bauhaus see O. Schlemmer, L. Moholy-Nagy, F. Molnar, The Theatre of the Bauhaus (Middletown, Conn.: Wesleyan University Press, 1961).

17 Shelter Magazine, May 1932.

18 Architectural Record, May 1930. Ideal theatres are a hobby of architects. See, for example, The Ideal Theatre: Eight Concepts (New York: The American Federation of Arts, 1962). When it comes time to build, the visions are stored and “community” or “cultural” interests take over. The results are lamentable. See A. H. Reiss's “Who Builds Theatres and Why” in this issue of TDR.

19 Assemblages, Environments, and Happenings (New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1960), 165-6. A similar history is presented by Harriet Janis and Rudi Blesh in Collage (Philadelphia and New York: Chilton, 1962). Kirby disagrees with these accounts and argues that the movement from painting to collage, assemblage, and environment is but one aspect of the “theatrical” nature of intermedia, and not the most important. “It is in Dada that we find the origins of the nonmatrixed performing and compartmented structure that are so basic to Happenings.” For Kirby's discussion see the introduction to his Happenings (New York: Dutton, 1965). For descriptions and scenarios of many environmental intermedia pieces see Kirby's book and T30.

20 Collected in Rosenberg's The Tradition of the New (New York: McGraw-Hill, 1965), p. 25. The quest for sources can become, in composer Morton Feldman's term, “mayflowering” and as such it is an intriguing but not very productive game. However, since I have begun playing that game, let me add that the work of the Russian Constructivists and the Italian Futurists also bears on the history of environmental staging.

21 It's rather sad to think about the New York Shakespeare Festival or the Avignon Festival. For the first a stage has been built in Central Park which does its best to make an outdoor setting indoors. When the Festival moves around New York it lugs its incongruent stages and equipment with it. At Avignon, the stage built in front of the castle neither successfully hides the facade nor makes productive use of it. In neither case has a negotiation been tried between the large environment and the staged event. Only the Greeks—see Epidaurus—knew how.

22 It remains to be seen whether the riots will offer a new prototype.

23 For an account of one of the best street theatres see the interview with Peter Schumann in T38.

24 The scenario appeared in my essay “Public Events for the Radical Theatre,” Village Voice, 7 September 1967. Accounts were printed in the Voice, 2 November 1967, the New York Times, 29 October 1967, and the March, 1968, Evergreen. The play we used as the root of the events was Robert Head's Kill Viet Cong, printed in T32.

25 Eugenio Barba, “Theatre Laboratory 13 Rzedow,” T27.

26 Shakespeare's half-quoted phrase deserves to be quoted in full: “the play's the thing/Wherein I'll catch the conscience of the king.” Certainly Hamlet didn't serve the playwright's intentions, but his own independent motives.

27 Cage, op.cit., pp. 53-54.

28 Grotowski, “Towards the Poor Theatre,” T35.

29 Interview with Grotowski to be published in the Fall, 1968 TDR.

30 Village Voice, 11 May 1967.

- 29

- Cited by