Abstract

Background

Osteoporosis is recognized as a serious health condition in developed as well as developing countries. There are no accurate estimates of the extent of the burden of osteoporosis in New Zealand. The purpose of this study was to estimate the economic burden of osteoporosis in New Zealand using data from international studies and population and health services information from New Zealand.

Objective

To estimate the number of osteoporotic fractures and cost of treatment and management of osteoporosis and osteoporotic fractures to the health system in New Zealand in 2007 and to project the future burden in 2013 and 2020.

Methods

Hospitalizations for hip fractures were combined with New Zealand census data and estimates from previous studies to estimate the expected number of osteoporotic vertebral, humeral, pelvic and other sites fractures in 2007. Health services usage and costs were estimated by combining data from New Zealand hospitals, the New Zealand Health Survey on the number of people diagnosed with osteoporosis, and the New Zealand Health Information Service (NZHIS) on pharmaceutical treatments. All prices are in New Zealand dollars ($NZ), year 2007 values. Losses in QALYs resulting from osteoporotic fractures were used to indicate the impact on morbidity and mortality. The lost QALYs and economic cost associated with osteoporosis were projected to 2013 and 2020 using population projections from the New Zealand census.

Results

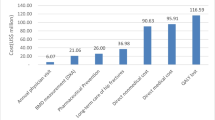

There were an estimated 84 354 osteoporotic fractures in New Zealand in 2007, including 3803 hip and 27994 vertebral fractures. Osteoporosis resulted in a loss of 11249 QALYs. The total direct cost of osteoporosis was $NZ330 million, including $NZ212 million to treat the fractures, $NZ85 million for care after fractures and $NZ34 million for treatment and management of the estimated 70 631 people diagnosed with osteoporosis. Sensitivity analysis suggested the results were robust to assumptions regarding the number of fractures receiving medical treatment. Hospitalization costs represented a significant component of total costs. The cost of treatment and management of osteoporosis is expected to increase to over $NZ391 million in 2013 and $NZ458 million in 2020, with the number of QALYs lost increasing to 13 205 in 2013 and 15 176 in 2020.

Conclusions

Osteoporosis and osteoporotic fractures create a significant burden on the health system in New Zealand. This study highlights the significant scope of the burden of osteoporosis and the potential gains that might be made from introducing interventions to mitigate the burden.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Johnell O, Kanis JA. An estimate of the worldwide prevalence and disability associated with osteoporotic fractures. Osteoporos Int 2006 Dec; 17(12): 1726–33

WHO. Prevention and management of osteoporosis: report of a WHO Scientific Group. Geneva: WHO, 2003. WHO Technical Report Series 921

Kanis JA, Oden A, Johnell O, et al. The burden of osteoporotic fractures: a method for setting intervention thresholds. Osteoporos Int 2001; 12(5): 417–27

Jones G, Nguyen T, Sambrook PN, et al. Symptomatic fracture incidence in elderly men and women: the Dubbo Osteoporosis Epidemiology Study (DOES). Osteoporos Int 1994 Sep; 4(5): 277–82

Rabenda V, Manette C, Lemmens R, et al. Prevalence and impact of osteoarthritis and osteoporosis on health-related quality of life among active subjects. Aging Clin Exp Res 2007 Feb; 19(1): 55–60

Pasco JA, Sanders KM, Hoekstra FM, et al. The human cost of fracture. Osteoporos Int 2005; 16: 2046–52

Taylor BC, Schreiner PJ, Stone KL, et al. Long-term prediction of incident hip fracture risk in elderly white women: study of osteoporotic fractures. J Am Geriatr Soc 2004 Sep; 52(9): 1479–86

Access Economics PL. The burden of brittle bones: costing osteoporosis in Australia. Canberra (ACT): Osteoporosis Australia, 2001 Sep

Kanis JA, Oden A, Johnell O, et al. The components of excess mortality after hip fracture. Bone 2003 May; 32(5): 468–73

Gold DT, Solimeo S. Osteoporosis and depression: a historical perspective. Curr Osteoporos Rep 2006 Dec; 4(4): 134–9

Pongchaiyakul C, Nguyen ND, Jones G, et al. Asymptomatic vertebral deformity as a major risk factor for subsequent fractures and mortality: a long-term prospective study. J Bone Miner Res 2005; 20(8): 1349–55

Lane A. Direct costs of osteoporosis for New Zealand women. Pharmacoeconomics 1996 Mar; 9(3): 231–45

PHARMAC. Zoledronic acid funded for osteoporosis [press release]. 2010 Aug 25 [online]. Available from URL: http://www.pharmac.govt.nz/2010/08/25/Zoledronic%20fund.pdf/text [Accessed 2010 Nov 18]

Metcalf S, Wilkinson T, Rasiah D. PHARMAC responds on agents to prevent osteoporotic fractures. N Z Med J 2006 Mar 10; 119(1230): U1895

Statistics New Zealand. Population projections [online]. Available from URL: http://www.stats.govt.nz/browse_for_stats/population/estimates_and_projections/demographic-trends-2005.aspx [Accessed 2007 Mar 14]

Ministry of Health. New Zealand Health Information Service. National minimum dataset (hospital events). 2007 [online]. Available from URL: http://www.nzhis.govt.nz/moh.nsf/pagesns/238 [Accessed 2010 Nov 18]

Cummings SR, Kelsey JL, Nevitt MC, et al. Epidemiology of osteoporosis and osteoporotic fractures. Epidemiol Rev 1985; 7: 178–208

Zethraeus N, Borgstrom F, Strom O, et al. Cost-effectiveness of the treatment and prevention of osteoporosis: a review of the literature and a reference model. Osteoporos Int 2007 Jan; 18(1): 9–23

Kanis JA, Oden A, Johnell O, et al. Excess mortality after hospitalisation for vertebral fracture. Osteoporos Int 2004 Feb; 15(2): 108–12

Dolan P, Torgerson DJ. The cost of treating osteoporotic fractures in the United Kingdom female population. Osteoporos Int 1998; 8(6): 611–7

Kanis JA, Borgstrom F, Zethraeus N, et al. Intervention thresholds for osteoporosis in the UK. Bone 2005; 36: 22–32

Center JR, Nguyen TV, Schneider D, et al. Mortality after all major types of osteoporotic fracture in men and women: an observational study. Lancet 1999 Mar 13; 353(9156): 878–82

Kanis JA, Johnell O, Oden A, et al. The risk and burden of vertebral fractures in Sweden. Osteoporos Int 2004; 15(1): 20–6

Data on file, Auckland District Health Board, 2007 Apr 15

Finnern HW, Sykes DP. The hospital cost of vertebral fractures in the EU: estimates using national datasets. Osteoporos Int 2003 Jun; 14(5): 429–36

Schwenkglenks M, Lippuner K, Hauselmann HJ, et al. A model of osteoporosis impact in Switzerland 2000–2020. Osteoporos Int 2005; 16: 659–71

Kanis JA, Brazier JE, Stevenson M, et al. Treatment of established osteoporosis: a systematic review and cost-utility analysis. Health Technol Assess 2002; 6(29): 1–146

Burge RT, King AB, Balda E, et al. Methodology for estimating current and future burden of osteoporosis is state populations: application to Florida in 2000 through 2025. Value Health 2003; 6(5): 574–83

Ministry of Health. Residential subsidy payments: a guide for the administrators of residential facilities. Dunedin: MOH, 2007 [online]. Available from URL: http://www.moh.govt.nz/moh.nsf/Files/sectorservices2/$file/residential-subsidy.pdf [Accessed 2010 Nov 18]

Ministry of Health. New Zealand health survey (2002/2003) [online]. Available from URL: http://www.nhc.health.govt.nz/moh.nsf/indexmh/dataandstatistics-survey-nzhealth [Accessed 2010 Nov 18]

Statistics New Zealand. Census of population and dwellings 2001 [online]. Available from URL: http://www.stats.govt.nz/census.aspx [Accessed 2010 Nov 18]

Publicly funded pharmaceutical usage data for New Zealand. Wellington: New Zealand Health Information Service, 2007 Jun 17. (Data on file)

New Zealand Ministry of Health. Evidence-based health objectives for the New Zealand health strategy. Public health intelligence, occasional bulletin no. 2. Wellington: Ministry of Health, 2001 Mar [online]. Available from URL: http://www.moh.govt.nz/moh.nsf/pagesmh/579 [Accessed 2007 Mar 12]

Orsini LS, Rouscup M, Long S, et al. Health care utilization and expenditures in the United States: a study of osteoporosis-related fractures. Osteoporos Int 2005; 16: 359–71

Jonsson B, Christiansen C, Johnell O, et al. Cost effectiveness of fracture prevention in established osteoporosis. Scand J Rheumatol 1996; 103(Suppl.): 30–8

Levy P, Levy E, Audran M, et al. The cost of osteoporosis in men: the French situation. Bone 2002 Apr; 30(4): 631–6

Brown JP, Josse RG, Scientific Advisory Council of the Osteoporosis Society of Canada. 2002 clinical practice guidelines for the diagnosis and management of osteoporosis in Canada [published erratum appears in CMAJ 2003 Feb 18; 168 (4): 400]. CMAJ 2002 Nov 12; 167(10 Suppl.): S1–34

Gullberg B, Johnell O, Kanis JA. World-wide projections for hip fracture. Osteoporos Int 1997; 7(5): 407–13

Acknowledgements

The paper is based on a report commissioned and funded by Osteoporosis New Zealand (http://www.bones.org.nz), a not-for-profit organization in New Zealand. The authors would like to acknowledge the expert clinical advice given by the Scientific Advisory Committee, especially Julia Gallagher, Professor Ian Reid, Dr Brandon Orr-Walker, Julie Harris and Gillian Robb. Paul Brown is now also employed by the School of Social Sciences, Humanities and Arts, University of California, Merced, CA, USA. The authors have no conflicts of interest that are directly relevant to the content of this article.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Brown, P., McNeill, R., Leung, W. et al. Current and future economic burden of osteoporosis in New Zealand. Appl Health Econ Health Policy 9, 111–123 (2011). https://doi.org/10.2165/11531500-000000000-00000

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.2165/11531500-000000000-00000