Summary

Abstract

Lansoprazole is an inhibitor of gastric acid secretion and also exhibits antibacterial activity against Helicobacter pylori in vitro.

Current therapy for peptic ulcer disease focuses on the eradication of H. pylori infection with maintenance therapy indicated in those patients who are not cured of H. pylori and those with ulcers resistant to healing. Lansoprazole 30mg combined with amoxicillin 1g, clarithromycin 250 or 500mg, or metronidazole 400mg twice daily was associated with eradication rates ranging from 71 to 94%, and ulcer healing rates were generally >80% in well designed studies. In addition, it was as effective as omeprazole- or rabeprazole-based regimens which included these antimicrobial agents. Maintenance therapy with lansoprazole 30 mg/day was significantly more effective than either placebo or ranitidine in preventing ulcer relapse. Importantly, preliminary data suggest that lansoprazole-based eradication therapy is effective in children and the elderly.

In the short-term treatment of patients with gastro-oesophageal reflux disease (GORD), lansoprazole 15, 30 or 60 mg/day was significantly more effective than placebo, ranitidine 300 mg/day or cisapride 40 mg/day and similar in efficacy to pantoprazole 40 mg/day in terms of healing of oesophagitis. Lansoprazole 30 mg/day, omeprazole 20 mg/day and pantoprazole 40 mg/day all provided similar symptom relief in these patients. In patients with healed oesophagitis, 12-month maintenance therapy with lansoprazole 15 or 30 mg/day prevented recurrence and was similar to or more effective than omeprazole 10 or 20 mg/day.

Available data in patients with NSAID-related disorders or acid-related dyspepsia suggest that lansoprazole is effective in these patients in terms of the prevention of NSAID-related gastrointestinal complications, ulcer healing and symptom relief.

Meta-analytic data and postmarketing surveillance in >30 000 patients indicate that lansoprazole is well tolerated both as monotherapy and in combination with antimicrobial agents. After lansoprazole monotherapy commonly reported adverse events included dose-dependent diarrhoea, nausea/vomiting, headache and abdominal pain. After short-term treatment in patients with peptic ulcer, GORD, dyspepsia and gastritis the incidence of adverse events associated with lansoprazole was generally ≤5%. Similar adverse events were seen in long-term trials, although the incidence was generally higher (≤10%). When lansoprazole was administered in combination with amoxicillin, clarithromycin or metronidazole adverse events included diarrhoea, headache and taste disturbance.

In conclusion, lansoprazole-based triple therapy is an effective treatment option for the eradication of H. pylori infection in patients with peptic ulcer disease. Preliminary data suggest it may have an important role in the management of this infection in children and the elderly. In the short-term management of GORD, lansoprazole monotherapy offers a more effective alternative to histamine H2-receptor antagonists and initial data indicate that it is an effective short-term treatment option in children and adolescents. In adults lansoprazole maintenance therapy is also an established treatment option for the long-term management of this chronic disease. Lansoprazole has a role in the treatment and prevention of NSAID-related ulcers and the treatment of acid-related dyspepsia; however, further studies are needed to confirm its place in these indications. Lansoprazole has emerged as a useful and well tolerated treatment option in the management of acid-related disorders.

Pharmacodynamic Properties

Lansoprazole inhibits gastric acid secretion via selective inhibition of the proton pump of the gastric parietal cell. Its active sulphenamide metabolites inactivate H+, K+-ATPase which catalyses the final step in the gastric acid secretion pathway.

Data from healthy volunteers showed that lansoprazole 30mg provided faster control of intragastric acidity than pantoprazole 40mg, rabeprazole 20mg and omeprazole 20 and 40mg administered once daily. However, in terms of mean intragastric 24-hour pH, lansoprazole 30mg was equivalent to omeprazole 40mg and better than pantoprazole 40mg and omeprazole 20mg. The duration of increased intragastric pH above pH 3 or 4 was significantly longer for lansoprazole 30mg versus pantoprazole 40mg or omeprazole 20mg; lansoprazole 15 mg/day and omeprazole 20 mg/day were equivalent.

Lansoprazole 30 mg/day significantly increased mean 24-hour gastric pH values compared with ranitidine 600 mg/day in a well designed crossover 5-day study. In addition, the percentage of time for which intragastric pH was maintained above 4 was significantly greater for lansoprazole than for ranitidine.

In a well designed crossover study in patients with gastro-oesophageal reflux disease (GORD), lansoprazole 30 mg/day and omeprazole 20 mg/day increased median daytime and night-time intragastric pH to a similar extent. Although, on day 5 of treatment the total time spent with a mean oesophageal pH value of <4 was significantly shorter for lansoprazole than for omeprazole.

In vitro, lansoprazole has demonstrated antibacterial activity against up to 113 Helicobacter pylori strains isolated from endoscopic biopsies. The minimum inhibitory concentrations required to inhibit the growth of 50% (MIC50) of H. pylori were generally within the range of 1 to 1.56 mg/L. Comparative MIC50values for other proton pump inhibitors were 12.5 to 16 mg/L for omeprazole and 50 mg/L for pantoprazole.

Lansoprazole at doses of 1 to 150 μmol/kg has also demonstrated dose-dependent gastroprotective properties in response to ethanol-HCl- and haemorrhagic shock-induced gastric mucosal damage in an in vivo study in Wistar rats.

Pharmacokinetic Properties

Lansoprazole is rapidly and completely absorbed, and displays linear kinetics over a dose range of 15 to 60mg. Maximum plasma concentrations (Cmax) of 0.75 to 1.15 mg/L were reached 1.5 to 2.2 hours after administration of a single dose of lansoprazole 30mg. Administration with food reduces both Cmax and area under the plasma concentration-time-curve (AUC) by 50% and delays the time to reach Cmax by 3.5 to 3.7 hours. Like all proton pump inhibitors, lansoprazole is highly protein bound (97%), rapidly metabolised in the liver by cytochrome P450 and has negligible renal clearance. Lansoprazole is also converted to its active metabolites in the gastric parietal cells. The elimination half-life (t½) of lansoprazole 30mg is approximately 0.9 to 1.6 hours. After a single oral dose of [14C]-lansoprazole one-third was excreted in the urine and two-thirds in the faeces.

In patients with renal impairment, t½ and AUC were decreased after administration of lansoprazole 60mg. AUC at steady state and t½ were increased in patients with varying degrees of hepatic impairment. In elderly patients t½ and AUC may be prolonged and clearance may be reduced. In one study, Cmax, AUC and t½ were increased after multiple doses of lansoprazole 30mg in patients with GORD compared with healthy volunteers.

Coadministration of lansoprazole 30mg, amoxicillin 1g and clarithromycin 500mg twice daily significantly prolongs t½ and increases the AUC of lansoprazole while increasing the Cmax, AUC12 and tmax of clarithromycin. The Cmax of paracetamol (acetaminophen) 1g was increased and the tmax was reduced when coadministered with lansoprazole 30mg. There were no clinically significant interactions when lansoprazole 30mg was coadministered with the following agents: roxithromycin 300mg twice daily, warfarin, indomethacin, ibuprofen, prednisolone, diazepam or terfenadine. Lansoprazole 60mg had no clinically significant effect on the pharmacokinetics of intravenous phenytoin, oral propranolol or theophylline, and multiple dose lansoprazole 60mg plus metronidazole 1g did not effect the pharmacokinetic properties of either agent.

Clinical Efficacy

Peptic ulcer disease

Eradication therapy combining a proton pump inhibitor and two antimicrobial agents is currently the most effective therapy, curing peptic ulcer disease and preventing ulcer recurrence in the majority of patients.

In well designed studies which included ≥300 patients, lansoprazole-based triple therapy regimens were equivalent to omeprazole- and rabeprazole-based regimens with respect to H. pylori eradication rates. Eradication rates for lansoprazole 30mg plus amoxicillin 1g and clarithromycin 250 or 500mg twice daily ranged from 72 to 92% compared with 62 to 93% for omeprazole 20mg combined with amoxicillin 750mg or lg and clarithromycin 250 or 500mg twice daily, and 87 and 86% for rabeprazole 10 or 20mg twice daily, amoxicillin 500mg 3 times daily and clarithromycin 200mg twice daily. When lansoprazole 30mg or omeprazole 20mg was combined with clarithromycin 250mg and metronidazole 400mg twice daily, eradication rates of >87% were observed. A higher eradication rate was observed with a two-week triple lansoprazole-based regimen than a one-week regimen in a subgroup of 71 patients from a larger study but this difference was not significant.

One-week triple therapy regimens with various combinations of lansoprazole 30mg or omeprazole 20mg plus amoxicillin 1g and/or clarithromycin 250 or 500mg and/or metronidazole 400mg administered twice daily generally show ulcer healing rates of >80%. Preliminary results obtained in a subgroup of patients indicate a greater incidence of ulcer healing was observed with a two-week lansoprazole-based triple therapy regimen although this was not significantly different compared with a one-week regimen.

There are few available data on the efficacy of eradication regimens in elderly patients and in children. Lansoprazole-based triple therapy regimens including a combination of amoxicillin, clarithromycin or metronidazole were equally effective in elderly patients, with eradication rates in the order of 80%. Similar eradication rates were observed after one weeks treatment with lansoprazole 30mg, omeprazole 20mg or pantoprazole 40mg all administered twice daily in combination with amoxicillin 1g twice daily and metronidazole 250mg 4 times daily for 1 week.

The optimal treatment regimen in children has not been established. Based on preliminary data in children and adolescents (2 to 18 years) triple therapy regimens using a lansoprazole dosage of >0.75 mg/kg/day combined with amoxicillin and clarithromycin had the highest eradication rates (87 and 92% in two trials), and ulcer healing was evident in 92% of children.

Gastro- Oesophageal reflux disease

For short-term treatment of patients with GORD, lansoprazole 15, 30 or 60 mg/day was significantly more effective in healing oesophagitis than placebo, ranitidine 300 or 600 mg/day or cisapride 20mg twice daily. Lansoprazole also reduced the percentage of days and nights with heartburn compared with ranitidine and placebo; the latter comparison was significantly in favour of lansoprazole. Lansoprazole and pantoprazole were equivalent in terms of endoscopically confirmed healing, and omeprazole and pantoprazole provided similar symptom relief to lansoprazole therapy in terms of the proportion of patients free of heartburn. However, in comparison with omeprazole, ranitidine and cisapride, lansoprazole provided significantly greater relief from heartburn.

In patients with healed oesophagitis, lansoprazole 15 or 30 mg/day administered as maintenance therapy prevented recurrence. However, data from 12-month studies offer no firm consensus on the most effective lansoprazole dosage for maintenance treatment.

Oesophagitis recurrence rates were <10% for both lansoprazole 30 mg/day and omeprazole 20 mg/day after 12 months’ maintenance therapy. The lower dosage of lansoprazole 15mg once daily was significantly more effective than omeprazole 10mg once daily in preventing relapse.

H. pylori status may affect the relapse rate in patients with GORD. In a randomised trial, all patients received lansoprazole 30mg daily for 10 days and H. pylori-positive patients also received amoxicillin and clarithromycin for 10 days then all patients received lansoprazole 30mg for 8 weeks. After 6 months of follow-up H. pylori-positive patients had a significantly faster relapse rate compared with either patients who had successful eradication therapy or patients who were H. pylori-negative. Severity of oesophagitis also significantly affected the relapse rate.

Lansoprazole 15 or 30mg once daily for 8 to 12 weeks healed erosive GORD in 27 children aged 1 to 12 years enrolled in a noncomparative trial. In a randomised double-blind trial in 63 children, lansoprazole 15mg relieved symptoms in only 69% of patients. Lansoprazole 1.3 to 1.5 mg/kg/day for 12 weeks resulted in endoscopically confirmed healing in 75% of children (n = 12) after treatment failure with ranitidine.

NSAID- related ulcers

In patients with NSAID-related gastric ulcers lansoprazole 15 and 30 mg/day was associated with a significantly higher incidence of ulcer healing, a lower incidence of daytime and night-time abdominal pain and a lower severity of day- or night-time abdominal pain and less antacid use per day than ranitidine 150mg twice daily. In over 2400 patients enrolled in randomised double-blind trials overall ulcer healing rates ranged from 64 to 76% with both dosages of lansoprazole compared with 47 to 53% for ranitidine recipients.

Lansoprazole 30 mg/day reduced ulcer relapse, irrespective of H. pylori status, in 61 patients with healed ulcers who continued to take naproxen 750 mg/day. An approximately 5-fold difference in relapse rates was noted between lansoprazole who had undergone H. pylori eradication and placebo recipients.

In a randomised double-blind study in 455 evaluable patients reported as an abstract, lansoprazole 15 and 30 mg/day was as effective as misoprostol 200μg four times daily in preventing NSAID-related ulcers.

Acid- related dyspepsia

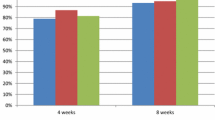

In 562 patients with acid-related dyspepsia, lansoprazole 15mg once daily provided significantly greater symptom relief (daytime heartburn and epigastric pain) compared with omeprazole 10mg once daily after 2 weeks of treatment in a randomised double-blind study; however, both agents were similarly effective at 4 weeks in an intention-to-treat analysis. Additional analyses suggest an interaction between the type of dyspepsia and treatment; at week 4 lansoprazole was more likely to provide symptom relief for patients with ulcer-like dyspepsia and omeprazole was more likely to be effective for those with reflux-like dyspepsia.

A per-protocol analysis in 283 patients with acid-related dyspepsia showed that lansoprazole 30mg once daily was significantly more effective than ranitidine 150mg twice daily in improving dyspepsia symptoms including freedom from daytime and night-time heartburn and night-time epigastric pain after 4 weeks of treatment in a randomised study.

Data from two abstracts also confirm that lansoprazole 15 and 30mg are superior in efficacy to placebo in providing symptomatic relief from dyspepsia in patients with nonulcer dyspepsia.

Tolerability Profile

In the US, the UK and The Netherlands, a review of clinical trials and postmarketing surveillance have evaluated the tolerability profile of lansoprazole in over 30 000 patients with GORD, gastric or duodenal ulcers, dyspepsia, Barrett’s oesophagus or Zollinger-Ellison syndrome. The most commonly reported adverse events,with lansoprazole 15, 30 and 60 mg/day therapy in patients with GORD or gastric or duodenal ulcer, were diarrhoea, which appears to be dose dependent, nausea, headache and abdominal pain.

A US review of clinical trials of ≤2 months’ duration found no significant differences between lansoprazole 15, 30 or 60 mg/day and omeprazole 20 mg/day with respect to headache, diarrhoea and nausea; these adverse events occurred with a frequency of ≤5%.

In 8-week trials in patients with GORD, NSAID-related gastric ulcers and acid-related dyspepsia lansoprazole 15 or 30 mg/day were generally associated with a similar incidence of adverse events compared with ranitidine 300 or 600 mg/day. In patients with GORD, nausea/vomiting, diarrhoea, abdominal pain and headache were most commonly reported; diarrhoea was the most frequently reported adverse event in patients with an NSAID-related ulcer.

Similar adverse events were observed in trials of 1 to 4 years’ duration in patients with GORD, peptic ulcer, gastritis or dyspepsia. However, the frequency of adverse events such as diarrhoea, headache, nausea/vomiting, dizziness and abdominal pain was generally higher (>10%) in longer-term trials. A similar type and frequency of events was observed in a 1-year trial in patients with duodenal ulcer administered lansoprazole 15 or 30 mg/day or ranitidine 150 mg/day.

The most commonly reported adverse events were diarrhoea, headache and taste disturbance when lansoprazole was administered in combination with amoxicillin, clarithromycin or metronidazole. Omeprazole-based triple therapy was generally similar in the type and frequency of adverse events observed. Notably, lansoprazole in combination with amoxicillin and clarithromycin had the highest incidence of diarrhoea, while lansoprazole plus clarithromycin and metronidazole had the lowest.

Dosage and Administration

Dosage recommendations for lansoprazole differ between countries. In brief, for the eradication of H. pylori US guidelines recommend a 10- or 14-day regimen consisting of lansoprazole 30mg, amoxicillin 1g and clarithromycin 500mg twice daily. In the UK, prescribing recommendations state that eradication therapy should consist of a twice-daily regimen of lansoprazole 30mg for 1 week plus two of either amoxicillin 1g, clarithromycin 500mg or metronidazole 400mg for 1 week. Maintenance therapy of 15 mg/day is recommended in both countries for patients with persistent duodenal ulcer symptoms.

For short-term treatment of GORD, 30 mg/day for 4 to 8 weeks is recommended in the UK; in the US treatment should be initiated with 15 mg/day for up to 8 weeks and this dosage may be increased to 30 mg/day for patients with erosive oesophagitis. Lansoprazole 15 mg/day is recommended for maintenance treatment to prevent recurrence in patients with healed GORD; this dosage may be increased to 30 mg/day in the UK.

US guidelines recommend administration of lansoprazole 30 mg/day for 8 weeks for the treatment of NSAID-related ulcers; according to UK guidelines lansoprazole 15 to 30 mg/day should be administered for 4 to 8 weeks. In the US, lansoprazole 15 mg/day for up to 12 weeks is recommended as prophylactic treatment in patients at risk of developing NSAID-related ulcers. Lansoprazole 15 to 30 mg/day may be administered to these patients according to UK guidelines.

At present there are no US recommendations for the treatment of acid-related dyspepsia. The UK prescribing guidelines recommend 2 to 4 weeks’ treatment with lansoprazole 15 to 30 mg/day as required.

Of note, lansoprazole should be taken before meals to avoid a reduction in the rate and extent of absorption. Although lansoprazole is usually administered once daily, it may be administered in two divided doses in the morning and evening in patients receiving ≥120mg daily.

Dosage adjustment of lansoprazole is not necessary in elderly patients or patients with mild renal or hepatic impairment, although, in patients with severe hepatic dysfunction a dosage reduction should be considered. There are currently no recommendations available concerning the use of lansoprazole in children.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Barradell LB, Faulds D, McTavish D. Lansoprazole: a review of its pharmacodynamic and pharmacokinetic properties and its therapeutic efficacy in acid-related disorders. Drugs 1992; 44: 225–50

Spencer CM, Faulds D. Lansoprazole: a reappraisal of its pharmacodynamic and pharmacokinetic properties, and its therapeutic efficacy in acid-related disorders. Drugs 1994 Sep; 48: 404–30

Langtry HD, Wilde MI. Lansoprazole: an update of its pharmacological properties and clinical efficacy in the management of acid-related disorders. Drugs 1997 Sep; 54: 473–500

Nishina K, Mikawa K, Takao Y, et al. A comparison of rabeprazole, lansoprazole, and ranitidine for improving preoperative gastric fluid property in adults undergoing elective surgery. Anesth Analg 2000 Mar; 90: 717–21

Goerg KJ, Mertens D, Goymann V. Lansoprazole versus misoprostol in the prevention of indomethacin-induced gastroduodenal lesions. A prospective randomized single-blind study in women undergoing hip joint endoprosthesis [abstract]. Gut 1997 Oct; 41 Suppl. 3: A7

Cohen H, Baldwin SN, Mukherji R, et al. A comparison of lansoprazole and sucralfate for the prophylaxis of stress-related mucosal damage in critically ill patients. Crit Care Med 2000 Dec; 28 Suppl. A185

Blandizzi C, Natale G, Gherardi G, et al. Acid-independent gastroprotective effects of lansoprazole in experimental mucosal injury. Dig Dis Sci 1999 Oct; 44: 2039–50

Ohara T, Arakawa T. Lansoprazole decreases peripheral blood monocytes and intercellular adhesion molecule-1-positive mononuclear cells. Dig Dis Sci 1999 Aug; 44: 1710–5

Nakao M, Malfertheiner P. Growth inhibitory and bactericidal activities of lansoprazole compared with those of omeprazole and pantoprazole against Helicobacter pylori. Helicobacter 1998 Mar; 3: 21–7

Stolte M, Meining A, Scifert E, et al. Treatment with lansoprazole also induces hypertrophy of the parietal cells of the stomach. Pathol Res Pract 2000; 196: 9–13

Rao BR, Kirch W. Cardiovascular effects of lansoprazole and nizatidine. J Noninvasive Cardiol 1998; 2(1): 29–34

Stolte M, Vieth M, Schmitz JM, et al. Effects of long-term treatment with proton pump inhibitors in gastro-oesophageal reflux disease on the histological findings in the lower oesophagus. Scand J Gastroenterol 2000 Nov; 35: 1125–30

Harder H, Teyssen S, Stephan F, et al. Effect of 7-day therapy with different doses of the proton pump inhibitor lansoprazole on the intragastric pH in healthy human subjects. Scand J Gastroenterol 1999 Jun; 34: 551–61

Geus WP, Mulder PG, Nicolai JJ, et al. Acid-inhibitory effects of omeprazole and lansoprazole in Helicobacter pylori-negative healthy subjects. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 1998 Apr; 12: 329–35

Bell N, Karol MD, Sachs G, et al. Duration of effect of lansoprazole on gastric pH and acid secretion in normal male volunteers. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2001 Jan; 15: 105–13

Wolf A, Wettstein AR, Drewe J, et al. Lansoprazole achieves faster control of intragastric acidity than pantoprazole or omeprazole after a single dose. Gastroenterology 2000 Apr; 118 Suppl. 2 (Pt 2): 1325

Tolman K, Taubel J, Warrington S, et al. Lansoprazole achieves faster control of intragastric acidity than rabeprazole within the first 5 hours of administration. Am J Gastroenterol 2000 Sep; 95: 2468

Thöring M, Hedenstrom H, Eriksson LS. Rapid effect of lansoprazole on intragastric pH: a crossover comparison with omeprazole. Scand J Gastroenterol 1999 Apr; 34: 341–5

Blum RA, Shi H, Karol MD, et al. The comparative effects of lansoprazole, omeprazole, and ranitidine in suppressing gastric acid secretion. Clin Ther 1997 Sep–Oct; 19: 1013–23

Thomson A, Appelman S, Sridhar S, et al. Lansoprazole or pantoprazole: which PPI provides faster and more profound acid suppression? Gut 1999 Nov; 45 Suppl. V: A106

Janczewska I, Sagar M, Sjöstedt S, et al. Comparison of the effect of lansoprazole and omeprazole on intragastric acidity and gastroesophageal reflux in patients with gastroesophageal reflux disease. Scand J Gastroenterol 1998 Dec; 33: 1239–43

Fera MT, Carbone M, De Sarro A, et al. Bactericidal activity of lansoprazole and three macrolides against Helicobacter pylori strains tested by the time-kill kinetic method. Int J Anti-microb Agents 1998 Nov; 10: 285–9

Alarcon T, Domingo D, Sánchez I, et al. In vitro activity of ebrotidine, ranitidine, omeprazole, lansoprazole, and bismuth citrate against clinical isolates of Helicobacter pylori. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis 1998 Apr; 17: 275–7

Vogt K, Hahn H. Bactericidal activity of lansoprazole and omeprazole against Helicobacter pylori in vitro. Arzneimittelforschung 1998 Jun; 48: 694–7

Malizia T, Tejada M, Marchetti F, et al. Synergic interactions of macrolides and proton-pump inhibitors against Helicobacter pylori: a comparative in-vitro study. J Antimicrob Chemother 1998 Mar; 41 Suppl. B: 29–35

Midolo PD, Turnidge JD, Lambert JR. Bactericidal activity and synergy studies of proton pump inhibitors and antibiotics against Helicobacter pylori in. vitro. J Antimicrob Chemother 1997 Mar; 39: 331–7

Nakayama I, Yamaji E, Hirata H, et al. Comparative in vitro antimicrobial activity of proton pump inhibitor lansoprazole against Helicobacter pylori [abstract]. 38th Interscience Conference on Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy; 1998 Sep 24; San Diego (CA), 280

Stedman CA, Barclay ML. Review article: comparison of the pharmacokinetics, acid suppression and efficacy of proton pump inhibitors. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2000 Aug; 14:963–78

Lansoprazole [online]. 2001 Mosby’s GenRx Update 2; 2001 Apr. Available from: URL: http://www.mosbysgenrx.com [Accessed 2001 Apr 9]

Barclay ML, Begg EJ, Robson RA, et al. Lansoprazole pharmacokinetics differ in patients with oesophagitis compared to healthy volunteers. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 1999 Sep; 13: 1215–9

Gunasekaran T, Pan W-J, Torres-Pinedo R, et al. Pharmacokinetics of lansoprazole in adolescent patients with gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD). Gastroenterology 2000 Apr; 118 Suppl. 2 (Pt 2): 1241

Mainz D, Borner K, Koeppe P, et al. Pharmacokinetics of lansoprazole, amoxicillin and clarithromycin when given single and concomitant [abstract no. 3066]. Presented at the 20th International Congress of Chemotherapy; 1997 Jun–Jul; Sydney

Kees F, Holstege A, Ittner KP, et al. Pharmacokinetic interaction between proton pump inhibitors and roxithromycin in volunteers. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2000 Apr; 14: 407–12

Karol MD, Locke CS, Cavanaugh JH. Lack of pharmacokinetic interaction between lansoprazole and intravenously administered phenytoin. J Clin Pharmacol 1999 Dec; 39: 1283–9

Karol MD, Locke CS, Cavanaugh JH. Lack of interaction between lansoprazole and propranolol, a pharmacokinetic and safety assessment. J Clin Pharmacol 2000 Mar; 40: 301–8

Dilger K, Zheng Z, Klotz U. Lack of drug interaction between omeprazole, lansoprazole, pantoprazole and theophylline. Br J Clin Pharmacol 1999 Sep; 48: 438–44

Pan WJ, Goldwater DR, Zhang Y, et al. Lack of a pharmacokinetic interaction between lansoprazole or pantoprazole and theophylline. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2000 Mar; 14: 345–52

Chassard D, Gualano V, Forestier S, et al. Effect of lansoprazole (L) on the steady-state pharmacokinetics of metronidazole (M) following concomitant administration of both drugs in 24 healthy volunteers [abstract]. Gastroenterology 1998 Apr 15; 114 Suppl. (Pt 2): 88

Sanaka M, Kuyama Y, Mineshita S, et al. Pharmacokinetic interaction between acetaminophen and lansoprazole. J Clin Gastroenterol 1999 Jul; 29: 56–8

Spinzi GC, Bierti L, Bortoli A, et al. Comparison of omeprazole and lansoprazole in short-term triple therapy for Helicobacter pylori infection. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 1998 May; 12: 433–8

Schwartz H, Krause R, Sahba B, et al. Triple versus dual therapy for eradicating Helicobacter pylori and preventing ulcer recurrence: a randomized, double-blind, multicenter study of lansoprazole, clarithromycin, and/or amoxicillin in different dosing regimens. Am J Gastroenterol 1998 Apr; 93: 584–90

Misiewicz JJ, Harris AW, Bardhan KD, et al. One week triple therapy for Helicobacter pylori: a multicentre comparative study. Lansoprazole Helicobacter Study Group [see comments]. Gut 1997 Dec; 41: 735–9

Sachs G. Proton pump inhibitors and acid-related diseases. Pharmacotherapy 1997 Jan-Feb; 17: 22–37

Grimley CE, Penny A, O’sullivan M, et al. Comparison of two 3-day Helicobacter pylori eradication regimens with a standard 1-week regimen. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 1999 Jul; 13: 869–73

Miwa H, Yamada T, Sato K, et al. Efficacy of reduced dosage of rabeprazole in PPI/AC therapy for Helicobacterpylori infection: comparison of 20 and 40 mg rabeprazole with 60 mg lansoprazole. Dig Dis Sci 2000 Jan; 45: 77–82

Jaup BH, Stenquist B, Norrby A. One-week bid therapy for H. pylori: a randomized comparison of three strategies on clinical outcome and side-effects [abstract]. Gut 1997 Oct; 41 Suppl. 3: A209

Lau CF, Tung SYM, Wong AMC, et al. Evaluation of two proton pump inhibitor-based triple therapies for Helicobacter pylori eradication in public hospital of Hong Kong [abstract]. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 1999 Mar; 14: A2

Malfertheiner P, Fischbach W, Layer P, et al. One-week low-dose lansoprazole triple therapy for eradication of Helicobacter pylori: a large multicentre, randomised trial. Gastroenterology 2000 Apr; 118 Suppl. 2 (Pt 2): 1269

Di Mario F, Buda A, Dal Bò N, et al. Different lansoprazole (LA) dosages in H. pylori eradication therapy: a prospective multicenter randomized study comparing 30 mg b.i.d. vs 15 mg b.i.d. Gut 1997; 41 Suppl. 3: 209

Maconi G, Russo A, Imbesi V, et al. Prolonging proton pump inhibitor-based anti-Helicobacter pylori treatment from one to two weeks in duodenal ulcer: is it worthwhile? Digest Liver Dis 2000; 32(4): 275–80

Pilotto A, Franceschi M, Leandro G, et al. Efficacy of 7 day lansoprazole-based triple therapy for Helicobacter pylori infection in elderly patients. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 1999 May; 14: 468–75

Pilotto A, Dal Bo N, Franceschi M, et al. Comparison of three proton pump inhibitors (PPI) in combination with amoxycillin and metronidazole for one week to cure Helicobacter pylori infection in the elderly [abstract]. Gut 1998 Sep; 43 Suppl. 2:91

Harris AW, Misiewicz JJ, Bardhan KD, et al. Incidence of duodenal ulcer healing after 1 week of proton pump inhibitor triple therapy for eradication of Helicobacter pylori. Lansoprazole Helicobacter Study Group. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 1998 Aug; 12: 741–5

Kato S, Ritsuno H, Ohnuma K, et al. Safety and efficacy of one-week triple therapy for eradicating Helicobacter pylori in children. Helicobacter 1998 Dec; 3: 278–82

Kalach N, Raymond J, Benhamou PH, et al. Spiramycin as an alternative to amoxicillin treatment associated with lansoprazole/metronidazole for Helicobacter pylori infection in children [letter]. Eur J Pediatr 1998 Jul; 157: 607–8

Shashidhar H, Peters J, Lin C-H, et al. A prospective trial of lansoprazole triple therapy for pediatric Helicobacter pylori infection. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 2000 Mar; 30: 276–82

Kalach N, Raymond J, Benhamou PH, et al. Short-term treatment with amoxycillin, clarithromycin and lansoprazole during Helicobacter pylori infection in children. Clin Microbiol Infect 1999; 5(4): 235–6

Dent J, Brun J, Fendrick AM, et al. An evidence-based appraisal of reflux disease management-the Genval Workshop Report. Gut 1999; 44 Suppl. 2: S1–16

Richter JE, Kovacs TO, Greski-Rose PA, et al. Lansoprazole in the treatment of heartburn in patients without erosive oeso-phagitis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 1999 Jun; 13: 795–804

Earnest DL, Dorsch E, Jones J, et al. A placebo-controlled dose-ranging study of lansoprazole in the management of reflux esophagitis. Am J Gastroenterol 1998 Feb; 93: 238–43

Mulder CJJ, Westerveld BD, Smit JM, et al. A comparison of omeprazole MUPS® 20mg, lansoprazole 30mg and pantoprazole 40 mg in the treatment of reflux oesophagitis: a multicenter trial. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 1999 Dec; 11: A73–4

Richter J, Kahrilas P, Sontag S, et al. Speed of heartburn relief: lansoprazole vs. omeprazole [abstract]. Am J Gastroenterol 2000 Sep; 95: 2431

Fass R, Murthy U, Hayden CW, et al. Omeprazole 40 mg once a day is equally effective as lansoprazole 30 mg twice a day in symptom control of patients with gastro-oesophageal reflux disease who are resistant to conventional-dose lansoprazole therapy — a prospective, randomized, multi-centre study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2000 Dec; 14: 1595–603

Dupas J-L, Houcke P, Giret-d’Orsay G, et al. First comparison pantoprazole versus lansoprazole in hospital and private practice patients with reflux esophagitis [abstract]. Gastroenterology 1998 Apr 15; 114 Suppl. (Pt 2): 110

Jansen JB, Van Oene JC. Standard-dose lansoprazole is more effective than high-dose ranitidine in achieving endoscopic healing and symptom relief in patients with moderately severe reflux oesophagitis. Dutch Lansoprazole Study Group. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 1999 Dec; 13: 1611–20

Richter JE, Campbell DR, Kahrilas P, et al. In non-erosive GERD, lansoprazole produces greater symptom relief than ranitidine [abstract]. Gastroenterology 1999 Apr; 116(Pt2): 292

Deboever G, Wagner C, Bourgeois N, et al. Lansoprazole 15 mg OD vs ranitidine 300 mg OD in reflux oesophagitis grade I [abstract]. Gut 2000 Dec; 47 Suppl. Ill: A59

Vicari F, Joubert-Collin M, Perié F. Efficacy and safety of lansoprazole 15 mg in the treatment of GOR symptoms. Comparison to cisapride 20 mg [abstract]. Gut 1999; 31 Suppl. 1:46

van Rensburg CJ, Schmidt SJ, Moola SA, et al. The efficacy and safety of lansoprazole (LAN) 30mg once daily vs cisapride (CIS) 20mg twice daily for 8 weeks in the acute treatment of erosive reflux oesophagitis (ERO) [abstract]. Gastroenterology 2000; 118(4) Suppl. 2 (Pt. 2): A1318

European Helicobacter Pylori Study Group (EHPSG). Current European concepts in the management of Helicobacter pylori infection. The Maastricht Consensus Report. Gut 1997 Jul; 41:8–13

Schwizer W, Thumshirn M, Dent J, et al. Helicobacter pylori and symptomatic relapse of gastro-oesophageal reflux disease: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2001 Jun 2; 357: 1738–42

Hatlebakk JG, Berstad A. Prognostic factors for relapse of reflux oesophagitis and symptoms during 12 months of therapy with lansoprazole. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 1997 Dec; 11: 1093–9

Roseveare C, Goggin P, Patel P, et al. A prospective randomised controlled trial comparing daily, alternate day and PRN lansoprazole in the maintenance treatment of oesophagitis [abstract]. Gastroenterology 1998 Apr 15; 114 Suppl. (Pt 2):271

Jansen J, Haeck PWE, Snel P, et al. What is the preferred dose of lansoprazole in the maintenance therapy of reflux oesophagitis? The results of a Dutch multi-center comparative trial [abstract]. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 1998 Dec; 10: A48–9

Carling L, Axelsson CK, Forssell H, et al. Lansoprazole and omeprazole in the prevention of relapse of reflux oesophagitis: a long-term comparative study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 1998 Oct; 12: 985–90

Bardhan KD, Crouch SL. Low dose lansoprazole is significantly superior to omeprazole in the prevention of relapse in patients with mild to moderate reflux oesophagitis [abstract]. UK and Eire Lansoprazole Study Group. Gastroenterology 1999 Apr; 116 (Pt 2): 118A–9A

Bardhan KD, Crouch SL. Low dose lansoprazole is significantly superior to omeprazole in the prevention of relapse in patients with mild to moderate reflux oesophagitis [abstract]. UK and Eire Lansoprazole Study Group. Gut 1999 Apr; 44 Suppl. 1: 113

Gupta SK, Tolia VK, Heyman MB, et al. Adolescent patients with gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD): results from a randomized trial of lansoprazole. Gastroenterology 2000 Apr; 118 Suppl. 2 (Pt 2): 1242

Tolia V, Ferry G, Gunasekaran T, et al. Efficacy of lansoprazole in the treatment of GERD in children. Am J Gastroenterol 2000 Sep; 95: 2446

Franco MT, Salvia G, Terrin G, et al. Lansoprazole in the treatment of gastro-oesophageal reflux disease in childhood. Digest Liver Dis 2000; 32(8): 660–6

Agrawal NM, Campbell DR, Safdi MA, et al. Superiority of lansoprazole vs ranitidine in healing nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug-associated gastric ulcers: results of a double-blind, randomized, multicenter study. NSAID-Associated Gastric Ulcer Study Group. Arch Intern Med 2000 May 22; 160: 1455–61

Elliott SL, Ferris RJ, Giraud AS, et al. Indomethacin damage ti rat gastric mucosa is markedly dependent on luminal pH. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol 1996; 23: 432–4

Goldstein J, Huang B, Feaheny K, et al. Healing and prevention of NSAID-associated ulcers in patients continuing to take NSAIDs-lansoprazole vs. ranitidine and lansoprazole vs. misoprostol vs. placebo [abstract]. Gut 1999 Nov; 45 Suppl. V: A101

Goldstein JL, Huang B, Collis CM, et al. PPI based healing of NSAID associated ulcers in patients continuing NSAIDs [abstract]. Am J Gastroenterol 2000 Sep; 95: 2452

Shah N, Winston B, Karvois D, et al. Effect of H. pylori status on healing of gastric ulcer in patients continuing to take NSAIDs and treated with lansoprazole or ranitidine. Gastroenterology 1998 Apr 15; 114 Suppl. (Pt 2): A83

Sontag S, Greski-Rose P, Lukasik N, et al. Lansoprazole heals NSAID-associated gastric ulcers (GUs) despite H. pylori (HP) infection and continued NSAID use [abstract]. Am J Gasteroenterol 1999; 94: 2620

Lai K-C, Lam S-K, Hui W-M, et al. Lansoprazole reduces ulcer relapse after eradication of Helicobacter pylori in NSAIDs users [abstract]. Gastroenterology 2000 Apr; 118 Suppl. 2 (Pt 1): 251

Lai K-C, Chu K-M, Hui W-M, et al. COX-2 inhibitor compared with proton pump inhibitor in the prevention of recurrent ulcer complications in high risk patients taking NSAIDs. Gastroenterology 2001; 120(5) Suppl. 1: A104

Jones R, Crouch SL. Low-dose lansoprazole provides greater relief of heartburn and epigastric pain than low-dose omeprazole in patients with acid-related dyspepsia. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 1999 Mar; 13: 413–9

Jones RH, Baxter G. Lansoprazole 30 mg daily versus ranitidine 150 mg b.d. in the treatment of acid-related dyspepsia in general practice. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 1997 Jun; 11: 541–6

Hengels KJ. Therapeutic efficacy of 15 mg lansoprazole mane in 269 patients suffering from non-ulcer dyspepsia (NUD): a multicentre, randomised, double-blind study [abstract]. Gut 1998 Sep; 43 Suppl. 2:89

Peura DA, Kovacs TO, Metz D, et al. Low-dose lansoprazole: effective for non-ulcer dyspepsia (NUD) [abstract]. Gastroenterology 2000; 118(4) Suppl. 2: A439

Freston JW, Rose PA, Heller CA, et al. Safety profile of Lansoprazole: the US clinical trial experience. Drug Saf 1999 Feb; 20: 195–205

Martin RM, Dunn NR, Freemantle S, et al. The rates of common adverse events reported during treatment with proton pump inhibitors used in general practice in England: cohort studies. Br J Clin Pharmacol 2000; 50(4): 366–72

Claessens A, Heerdink ER, van Eijk JTM, et al. Safety review in 10,008 users of lansoprazole in daily practice. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 2000; 9(5): 383–91

TAP Pharmaceutical Products Inc. Prevacid (Lansoprazole): Complete Prescribing Information. TAP Pharmaceuticals Inc, Complete prescribing information Nov 2000 [online]. Available from: URL: http://www.prevacid.com/pro/comppi.cfm

Bardhan KD, Crowe J, Thompson RP, et al. Lansoprazole is superior to ranitidine as maintenance treatment for the prevention of duodenal ulcer relapse. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 1999 Jun; 13: 827–32

TAP Pharmaceutical Products Inc. Prevpac (lansoprazole/amoxicillin/clarithromycin): Complete Prescribing Information. TAP Pharmaceuticals Inc, Complete prescribing information Jul 2000. Available from: URL: http://www.prevacid.com/pro/pacpi/paccomppi.cfm

Shashidhar H, Peters J, Rabah R, et al. Lansoprazole in the treatment of H. pylori infection in children [abstract]. Gastroenterology 1998 Apr 15; 114 Suppl. (Pt 2): A284

Tolia V, Fitzgerald J, Hassall E, et al. Safety of lansoprazole in the treatment of GERD in children. Am J Gastroenterol 2000 Sep; 95: 2447

AHFS Drug Information. Lansoprazole. American Society of Health System Pharmacists; 2001 Information

British National Formulary. Ulcer healing drugs. No. 41. London: The Pharmaceutical Press, 2001 Mar

Howden CW, Hunt RH. Guidelines for the management of Helicobacter pylori infection. Am J Gastroenterol 1998; 93(12): 2330–8

Berardi RR, Welage LS. Proton-pump inhibitors in acid-related diseases. Am J Health Sys Pharm 1998; 55(21): 2289–98

Horn J. The proton-pump inhibitors: similarities and differences. Clin Ther 2000; 22(3): 266–80

Hoffman JS. Pharmacological therapy of Helicobacter pylori infection. Semin Gastrointest Dis 1997 Jul; 8: 156–63

Brown LF, Wilson DE. Gastroduodenal ulcers: causes, diagnosis, prevention and treatment. Compr Ther 1999; 25(1): 30–8

Welage LS, Berardi RR. Evaluation of omeprazole, lansoprazole, pantoprazole, and rabeprazole in the treatment of acid-related diseases. J Am Pharm Assoc Wash 2000 Jan–Feb; 40: 52–62. quiz 121–3

Hoffman JS, Cave DR. Treatment of Helicobacter pylori [gastrointestinal infections]. Curr Opin Gastroenterol 2001; 17(1): 30–4

Go FM, Vakil N. Treatment of Helicobacter pylori [gastrointestinal infections]. Curr Opin Gastroenterol 1999; 15(1): 72

Hassall E. Peptic ulcer disease and current approaches to Helicobacter pylori. J Pediatr 2001; 138(4): 462–8

Hassall E. Guidelines for approaching suspected peptic ulcer disease or H. pylori infection: where we are in paediatrics and how we got here. J Pediatr Gasteroenterol Nutr 2001; 32: 405–6

Gold BD, Colletti RB, Abbott M, et al. Helicobacter pylori infection in children: recommendations for diagnosis and treatment. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 2000; 31(5): 490–7

Kovacs TO, Campbell D, Richter J, et al. Double-blind comparison of lansoprazole 15 mg, lansoprazole 30 mg and placebo as maintenance therapy in patients with healed duodenal ulcers resistant to H2-receptor antagonists. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 1999 Jul; 13: 959–67

Lanza F, Goff J, Silvers D, et al. Prevention of duodenal ulcer recurrence with 15 mg lansoprazole: a double-blind placebo-controlled study. Lansoprazole Study Group. Dig Dis Sci 1997 Dec; 42: 2529–36

Kovacs TO, Campbell D, Haber M, et al. Double-blind comparison of lansoprazole 15 mg, lansoprazole 30 mg, and placebo in the maintenance of healed gastric ulcer. Dig Dis Sci 1998 Apr; 43: 779–85

Richter JE. Long-term management of gastroesophageal reflux disease and its complications. Am J Gastroenterol 1997 Apr; 92 (4 Suppl.): 30S–34S. discussion 34S–35S

DiPalma JA. Management of severe gastroesophageal reflux disease. J Clin Gastroenterol 2001; 32(1): 19–26

DeVault KR, Castell DO, Updated guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of gastroesophageal disease. The Practice Parameters Committee of the American College of Gastroenterology. Practice Guidelines. Am J Gastroenterol 1999; 94(6): 1434–42

Lagergren J, Bergström R, Lindgren A, et al. Symptomatic gastroesophageal reflux as a risk factor for esophageal adenocarcinoma. N Engl J Med 1999; 340(11): 825–31

Ferriman A. UK licence for cisapride suspended. BMJ 2000 Jul 29; 312: 259

Henney JE. Withdrawal of troglitazone and cisapride. JAMA 2000; 283(17): 2228

Gottlieb S. FDA tells doctors to use heartburn drug as a last resort. BMJ 2000 Feb 5; 320: 336

Gupta S, Hassall EG, Book LS, et al. Presenting symptoms (Sxs) or erosive (EE) and non-erosive esophagitis (NEE) in children. Gastroenterology 2001; 120 Suppl. 1: 422

Cucchiara S, Franco MT, Terrin G, et al. Role of drug therapy in the treatment of gastro-oesophageal reflux disorder in children. Paediatr Drugs 2000; 2(4): 263–72

Israel DM, Hassall E. Omeprazole and other proton pump inhibitors: pharmacology, efficacy, and safety, with special reference to use in children [invited review]. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 1998; 27(5): 568–79

Hassall E, Israel D, Shepherd R, et al. Omeprazole for treatment of chronic erosive esophagitis in children: a multicenter study of efficacy, safety, tolerability and dose requirements. J Pediatr 2000; 137(6): 800–7

Hassall E, International Pediatric Study Group. Omeprazole for maintenance therapy of erosive esophagitis in children [abstract no. 3610]. Gastroenterology 2000; 118 Suppl. 2: A658–9

Lanza FL. A guideline for the treatment and prevention of NSAID-induced ulcers. Am J Gastroenterol 1998; 93(11): 2037–46

Schoenfeld P, Kimmey MB, Scheiman J, et al. Review article: nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug-associated gastrointestinal complications — guidelines for prevention and treatment. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 1999; 13(10): 1273–85

Talley NJ. Therapeutic options in nonulcer dyspepsia. J Clin Gastroenterol 2001; 32(4): 286–93

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Matheson, A.J., Jarvis, B. Lansoprazole. Drugs 61, 1801–1833 (2001). https://doi.org/10.2165/00003495-200161120-00011

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.2165/00003495-200161120-00011