Caring communities as collective learning process: findings and lessons learned from a participatory research project in Austria

Introduction

Let us recall the fact that dying is first and foremost a social process (1) and can be understood “as a shared set of overt social exchanges between dying individuals and those who care for them”(2). Thus, end-of-life care has to take into account these social and relational dimensions of caring (3,4) and focus attention on the supportive resources of social systems and (the web of) care relationships (5). This represents an extremely important complement to face to face, person-centred and service-driven care philosophies and practices.

For a long time, professionalized end-of-life care in modern Western societies regarded care for the dying as a medical challenge, which had to be organized and managed through social and health care organizations. The process of institutionalization and medicalization of dying in modernity has evoked counter movements from the 1960s onwards, in particular the hospice philosophy and the palliative care approach (6,7). This marked the beginning of a new—institutionally very successful—era of specialized end-of-life care in many global regions (8) which still lasts. Despite all these developments, the fundamental societal challenge of (re)integrating the dying, death and grief into a community’s everyday life and overcoming the institutionalization and professional specialization of care for the dying, could not be met.

From the late 1990s onwards, maybe as another counter movement—a wide range of practices and international efforts were undertaken, specifically focussing on the meaning of social determinants in improving health and wellbeing in all phases of life, including its final phase: dying and death (9). Incorporating principles of health-promotion into end-of-life care (10-12), this new public health approach “can be understood as a series of social efforts by communities, governments, state institutions and social or medical care organisations that aim to improve health and wellbeing in the face of life-limiting illness” (13). Many of these initiatives and projects are often described using the phrase “compassionate communities” (12,14). In German-speaking countries, the term “caring communities” is widely used. First studies indicate a promisingly potential impact of a new public health approach to end-of-life care (13). In particular, these studies highlight that community development interventions have manifold beneficial effects on the quality of end-of-life care, on improving social networks and on people’s “death literacy” (15-18).

Making up the balance of the past almost twenty years in new public health end-of-life care we can identify three phases of development: First, the implementation of health-promoting palliative care models, in which hospices and palliative care units reoriented their organizational culture and practice towards community-based care and new community partnerships (18); second, extending this first phase by a broader engagement of communities by participatory processes and building up community programmes, mostly through hospice and palliative care providers, to some extent also through other social care organizations (9,14); third, developing care culture at the end-of-life in whole communities, districts, municipalities, cities etc. towards citizen-led care through governing end-of-life care in co-responsibility of the local government, of partners from the care network and partners from diverse areas of the community or city (e.g., schools, arts, clubs, parish, businesses, etc.). In those cases, care organizations are merely one of many partners in a broader process of initiating citizen participation and engagement in community care and in implementing compassionate cities guidelines and programmes (19). Initial experiences show that it is in this third phase, where new partnerships with other sectors in the community, such as elderly and dementia care or support for refugees and marginalized populations and others, occur.

As part of this third phase of promoting compassionate or caring communities, we have undertaken the model project entitled “Caring Community in Living and Dying” in the municipality of Landeck, Austria, to encourage citizen-oriented approaches in elderly- and end-of-life care in German-speaking countries.

Interest and objective

In this paper, we present core findings and the analysis of our “lessons learned” from the project in order to contribute to further discourse and practice-based developments in the field of compassionate and caring communities. We concentrated on the following key questions: what are the deeper ideas behind caring communities? What is the essence of caring communities and what constitutes a caring community? From our point of view, the underlying assumptions behind caring communities remain too often implicit and taken for granted. In reality, they are also subject to a plurality of positions and traditions so that “caring communities” can also be considered as a contested concept. Our findings should contribute to deepening the conceptual framework of caring communities as well as to highlighting the potentially significant role of community-based participatory research in processes of collective learning and cultivating shared care culture in elderly- and end-of-life care. Finally, we discuss critical aspects and preconditions of sustainable caring community progresses for the future.

Methods

Study setting: the project “Caring Community in Living in Dying”

The municipality of Landeck, where our project took place, is a district capital with 8,000 inhabitants, situated in the rural mountain region of western Tyrol in Austria. To reach the public and get citizens involved (20), we established a project-partnership with the local government and the Tyrolean Hospice Association and jointly set up a community-based participatory research (21) process. The mayor and the chairman of the municipality’s social committee, both functioned as co-initiators and took over co-ownership of the model-project from the beginning. Landeck represented the ideal model region to develop a citizen-oriented caring community project due to the absence of specialized palliative care services and the existence of long-established civil society initiatives. The project aimed to raise awareness about existential questions concerning vulnerability, dying and loss and strengthen personal handling with these issues. Another objective was to foster support for older and vulnerable people and—specifically—informal caregivers.

Research design and methods

The overall project design followed a community-based participatory research approach. In this, research is understood as a collaborative process that engages researchers and community members in knowledge generation, capacity building and action for social change to improve community health and well-being as well as to reduce health disparities (22,23). Referring to the public-health end-of life care movement (23) the focus was not primarily to change peoples’ behaviour but to empower them, to enable new relationships and networks, to facilitate cultural shifts in organizing care and to act as researchers in an advocatory manner for people concerned. The two-year project was divided into three phases, extended by a very important pre-phase to build up trust and commitment in the community and therefore to create good preconditions, as illustrated in Table 1.

Full table

Tables 2,3 outline the main interventions and initiatives, and contextualize the research settings and data within the overall project process.

Full table

Full table

Methodological approach throughout the first project phase

The findings from the first phase (“survey”) are based on the qualitative analysis of a series of focus groups and individual interviews with community members. The sampling (see Table 2) depended on our “door-openers” from the local hospice group. This entailed (I) a focus on the situation of caring relatives and (II) reaching those who had been in contact with informal (volunteers, self-help groups) or formal caregivers. Our findings focus on characteristics and attributes of care relationships at a community level. We have described details of the methodology, dispositive analysis (24), and results of this research in more depth elsewhere (25).

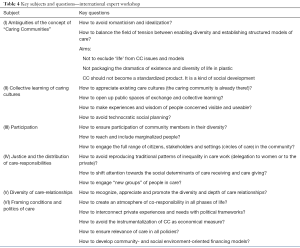

Meta-analyses and lessons learned

Our lessons learned are based on two types of data: on the one hand on the findings of the survey from the first phase; on the other hand on a reflective analysis of an international expert workshop on caring communities, where our experiences and insights were discussed in the light of international caring community models, initial experiences, and expertise. In the post-project phase, we hosted this first international expert workshop on caring communities in Vienna. Forty experts from Germany, Switzerland and Austria with diverse backgrounds in the field of social and health care (hospice- and palliative care, community and neighbourhood development, academics, politicians, project developers, etc.) were invited to exchange their knowledge and experiences in community care. We documented the expert workshop in two ways: (I) main discussions were tape-recorded and (II) the participants self-documented individually an important thought or a central claim for the future development of caring communities as well as arguments and reflections supporting these statements (n=32 “thesis-papers”) with regard to six central issues that emerged during the first half of the workshop. These issues were: (I) ambiguities of the concept; (II) collective learning of caring cultures; (III) participation; (IV) justice of the distribution of care-responsibilities; (V) diversity of care-relationships; (VI) framing conditions and politics of care. Table 4 illustrates the key questions and issues discussed.

Full table

Note on research ethics

In Austria, no formal process of ethical approval is required to carry out this type of participatory research and developmental project. Concerning the research for the survey-phase of the project, we obtained informed consent from all individual participants included in the study. Dialogue partners could withdraw from their participation in the study at any time. We anonymized all transcripts and ensured confidentiality, data protection and privacy. On these grounds, we were able to ensure voluntary participation.

Concerning the expert workshop, we provided a comprehensive documentation of the workshop to the participants and obtained consent for publishing the workshop results.

Results

In the following, we present our findings on two different but interrelated levels which, in our view, provide important insights to better understand the qualities and preconditions of care networks in elderly- and end-of-life care, and contribute to enrich the public health palliative care discourse and further development of caring communities. (I) The first level illustrates findings of the research done within the project as an answer to the following questions: What are qualitative dimensions and attributes of a caring community from the perspective of people concerned in the community? Therefore, which aspects and dimensions must we bear in mind for prospective initiatives in promoting care networks? (II) On the second level we discuss our “lessons learned” as theoretical and practical conclusions in reflecting the significance of the “care web ingredients” in relation to the results of the international expert workshop.

Qualities and attributes of a caring community: key research findings in first project phase

In the first phase of the project, we generated knowledge about the local care experiences, needs and practices. Based on this we initiated a process of sharing care narratives on diverse levels of the community and in various settings to enhance mutual understanding; for instance, from local politicians about difficult life situations of family caregivers.

Hence, we obtained qualitative characteristics of a supportive culture of care from the perspective of community members as a crucial knowledge base. These qualities come to life through individuals and organizations in their different roles, networks and as a shared characteristic of the community. Our findings do not describe dimensions of direct care (assistance in activities of daily living such as dressing, eating, washing, etc.) or “care” in the sense of funding or creating political conditions but the web of relationships that support the immediate care relationship. According to the relational dimensions of care, stressed by care ethicists (4,14), the web of relationships or “care web” should not be understood as centred upon a single person, whether the ill or dying person or the family carer, but rather upon their relationship, to one another and with others. Even if many of our interview partners were family carers, none of them described solely their personal situation but rather the difficult arrangement of home care in the relational interplay between themselves and their mother or father or other persons being cared for. At this point, we merely give a sketch of the qualities, since it is described in more detail elsewhere (25). The key qualities and attributes, which should be brought to life through the collective of the community and its various care relationships, are shown in Table 5.

Full table

“Lessons learned”: reflections on our findings of the first project phase and international expert workshop

Our “lessons learned” interlink the “care-ingredients”, with our reflection on the project process and, in particular, with the general results of the international expert workshop (for an overview see Table 4). In so doing, we connect practical and theoretical considerations that could serve as stimulus for other researchers and project developers in the field of caring and compassionate communities.

The caring community is already there: making it visible and learning from it

Through our approach of initiating caring communities by the support of participatory research, we became aware of the richness and diversity of existing care-relationships in the community of Landeck—despite community members identifying many problems. For this reason, the manner how researchers or community developers “enter” the field and relate to local community members and actors seems crucial to us. We are sceptical about understanding “caring community” as a concept that can be “implemented” in a standardized way. This sceptical point of view was also brought forward and even reinforced by experts in our reflection workshop. Consequently, “caring communities” should not be seen as a strict programme which can simply be put into practice, but as a type of framing, mutual care philosophy, which has to be translated into concrete, localized practices in collaboration with the community. Additionally, and this is probably even more important, caring culture and mutual support in everyday life are already there, which means that the caring community is present all along. Hence, the first and foremost task is to support the community in recognizing and appreciating their existing—sometimes tacit—care practices and raise awareness of—possibly hidden—care needs and marginalized community members. As well as hospice philosophy and appropriate end-of-life care depends very much on the ability to listen (28,29), project-developers and researchers have to listen, in order to appreciate, understand, and to make the local care culture and practices visible. In this sense, a caring community process gives opportunities to do so, opens spaces in the community to share knowledge, exchange experiences and invite people to participate and engage. Additionally, researchers should always have an open mind about learning for their own lives. As researchers and interviewers, we, for example, learned a lot from our conversation partners. In one focus group with family caregivers, an old woman, after listening to our questions, suddenly reversed the roles. She started to ask us—relatively young men—about our practice in sharing our care tasks and responsibilities in our families.

Caring communities as a collective learning process (I): the benefits of “participatory research”

It is by no means necessary to use and involve research in caring community processes. People care for each other in a very attentive and imaginative manner without professionals, external care-programmes, or researchers. Still, as far as our experience goes, research can (potentially) play a supporting and enabling role. If we assume that a caring community is and should be a kind of “learning community”, we need to be mindful of the role of research. Therefore, participatory action research might be a suitable approach, trying to ensure broad involvement of community members and enable the co-production of knowledge and a kind of reciprocity between participants and the research team according to attentive research ethics (23). Sustainable changes in communities should be introduced through self-development rather than one-sided interventions imposed by researchers. The critical objective should be to enable and empower (30). In this intersection of science and practice, community-based participatory research—at best—can help to improve health equity (31), and has the potential to address specific gaps in research on palliative care (21). This is congruent with current discourses on research in public health and end-of-life care (32).

Collective learning and fostering connections and relationships between community members requires more than managing interests and processes. This is why we felt obliged to an interpretation of participatory research that takes serious the concern of gaining knowledge in close exchange and together with people from the community (33); as far as possible, and with all its failures and pragmatic limitations. Therefore, the data collected throughout the project process was prepared to set the ground for diverse interventions. Insights, key issues and quotations served as stimulus for e.g., in-depth discussions, reflecting political frameworks in the steering committee of the municipality, future workshops or a citizen forum in the town hall. Varying research settings of surveys, local networking and public engagement allowed the participating inhabitants of Landeck to exchange existential experiences, express their needs, receive information and share common knowledge of local care practices and resources, develop prospects of local care policy and engage in various local community initiatives. The project intervention merely unlocked potentials for change and new pathways for improving the local care web. Following to the project process, four municipalities established the formal role of a care-coordinator, in particular to foster the qualities of “moderating care arrangements” and “vicariously organizing care” (see “ingredients” at Table 5). Moreover, a group of citizens, informal and formal caregivers founded an association called “Care Network Landeck” that continues caring community initiatives, such as networking (“keeping an eye on each other”), running a public last-aid course (“sharing wisdom of care”), organizing relief for family caregivers (“enabling freedom from care—“Sorglosigkeit”).

Making citizen wisdom and knowledge available for the community

To spread the generated knowledge to the broader community, we presented small reports at the local television and published (with the quoted participants’ consent) a series of articles in the local newspapers. In addition, we put together a little handbook for reflection representing the communities’ “wisdom of care”, which collates quotations, comments, questions and insights and portrays the role of informal caregivers in a novel way. It acknowledges family caregivers for their practical knowledge and care wisdom and by doing so, dispels the popular belief that informal carers are constantly in need to help. Informal caregivers can use the booklet as support in their everyday care work in the community.

This initiative of the booklet was triggered by insights from our conversations with family caregivers and volunteers, which demonstrated an important difference between two types of care knowledge; the competency of experts and “wisdom” (see Table 5: “contributing specific competencies” and “sharing life experience”). The competency of professional experts—people, who were trained in applying expertise and/or scientific knowledge in a clearly defined field—refers to dealing with (health care) problems like diseases or needs in the field of nursing care and so on. To a certain extent, these problems can be handled in predefined ways. In contrast, wisdom—more or less cultivated by all people (lay individuals or professionals) in their experience as interrelated and finite human beings—as such does not deal with problems that in principle (even if not always at the time) can be “solved”. It rather refers to “mysteries”, which ultimately cannot be “solved” but can only be addressed (34). We cannot, for example, “solve” the “problem” of death or the passing of time. We can only address these issues as mysteries and develop an existential (philosophical, spiritual) position towards them. In some cases, where there is nothing to be cured, the most relevant function of care may be the facilitation of an inner dialogue on existential issues to adopt a new and supportive ethos. Supporting people in being more aware of their own “tacit knowledge and resources” and of other community members’ “wisdom”, represents a small but important step during an ongoing process of social, cultural and ethical learning. By empowering citizens in their personal approaches and dealings with vulnerability—in other words, in raising their death literacy (17) —caring communities also unfold a certain a capacity to counter-balance the frequent predominance of expert-knowledge in care.

Caring Communities as a collective learning process (II): reflecting and processing the question of a good life until the end

This idea of developing “care-wisdom” in the community and rooting caring communities in sharing and reflecting crucial life experiences leads us back to the basic ideas of ancient philosophy as a daily critical reflection and dialogical examination of life with and for others in the community (35). In this sense, the saying that hospice is an attitude or a philosophy rather than a building, is more than a bon mot. The very concept of “hospice” and “palliative care” work and any daily practices where hospice cultures are lived, provides evidence that addressing existential (“spiritual”, “ethical”, “philosophical”) questions is a fundamental part of end-of-life care. According to a famous definition of the German existentialist and psychiatrist Karl Jaspers (36), becoming aware of “borderline situations” is—besides wonder and doubt—the fundamental origin of philosophical questioning. Jaspers refers to the ancient Stoics and the tradition of Socrates and Hellenistic philosophy. Events such as death, suffering, and loss, the realisation of the body’s vulnerability and the finitude of existence are all borderline situations par excellence. Therefore, places of (end-of-life) care can be perceived as places of philosophical questioning that allow people to “learn how to live and learn how to die,” as Seneca and Socrates would have put it (37), and where the dying become the “teachers” of the living (38). Philosophy, in the Socratic and Hellenistic paradigm, can be understood as “way of life” (35), as an exercise and as an integral part of everyday life. Philosophy is not conceived as something which is first theoretical and then practical. It is not developed in seminars or on a piece of paper, i.e., in the procedural and organizational forms of mere theory or a primarily theoretical concept of philosophy. Instead it is, from the very beginning onwards, seen as a process that takes place in practical life and offers an opportunity to examine and question one’s own (caring) experiences in life.

Even more, for Socrates and his successors, philosophical “interventions at the market place” had a deep political meaning, contributing to the search for the community’s good life. The participants of philosophical inquiries enter a process of mutual understanding and collective self-enlightenment on the base of personal recollection and experience; in philosophical terms: (collective and personal) practical wisdom is being cultivated (39,40).

One of our most important lessons learned—and one of the greatest challenges in developing a caring community from this point of view—is to take into account and facilitate the “political” role of (“philosophically”) reflecting caring experiences and the tacit “wisdom” of carers and people concerned. This ultimately empowers citizens to develop positions and their own language for dealing with crucial questions of living and dying and to immediately link perceived “existential” experience and practice with social and political conditions and questions of power.

This perspective corresponds very much to core insights in ethics of care. The political philosopher and care ethicist Joan Tronto (41) suggests that a caring society requires settings, where people can learn from and about the lives of others (“sharing life experience”), on the one hand; and also political spaces within “caring institutions” (and communities, as we may add), where people can address power relations and needs-interpretation (42), on the other hand. Thus, one core mission of caring community processes is to create environments for this purpose. In this sense, “philosophical practice” within the participatory research process enables and represents a social learning process in the community, bridging the private and the political (public).

- Example: Learning from stories for the “politics” of care.

Philosophical thinking, ethical reflection and storytelling may have a great value in themselves. However, if they are meant to have an impact on community life, on the care culture of a community, it is necessary to take care-stories as reasons to think about the social care conditions and fields of tension in the society. If the care-narratives of community members illustrate existential struggles with feelings of guilt, unfairness, not being recognized etc., conditions should be discussed, that allow people not to feel guilty when caring for others or that ensure that care work, does not remain unrecognized and unappreciated.

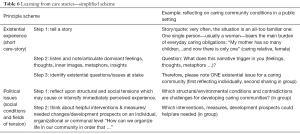

Ethics as an ongoing social learning process entails roughly the following elements of organizing and designing communal ethics (40) and common existential reflections:

- Creating a framework which allows participation in other people’s destiny and views beyond social roles.

- Organizing and facilitating the enlargement of a care network by providing a communication platform to the different actors involved.

- Favouring the deepening of life experience and wisdom in key aspects of living and dying.

- Identifying social challenges and raising crucial questions of life in society/community.

- Ensuring that knowledge, questions, and proposed measures can be passed on to others to enhance common care knowledge and to address responsible persons and bodies.

In the course of various community projects, we developed easy methods and guidelines, to deal with these elements. Most of them are following a simplified scheme, illustrated in Table 6 (40).

Full table

In Landeck, for example, we hosted a citizens’ forum in the town hall, where community members, people concerned, formal and informal caregivers and local politicians discussed prospects for the caring community. Based on our data, we introduced six topics through citing statements of our conversation partners and giving brief explanations (as quotes/short care-stories). The six themes were: Supporting family carers; measures against social isolation in old age; life upheavals and prevention; caring without guilt/bad conscience; care work and justice; strengthening neighbourhood culture. Inspired by the quotes, and in the light of their own experiences, the community members (n=95) developed 45 concrete citizen suggestion cards addressed to the local municipal policy. Most suggested measures concerned the topic areas: strengthening neighbourhood culture; social participation of vulnerable and marginalized people; receiving information and coordination of care; and spaces for conversation and talking about care experiences and needs.

Dealing with care (in)justice

Through our interviews and discussions in the community, we identified “political” issues, issues where the “private”—the experiences of family caregivers—is political, for example concerning a just distribution of care work or power relations in caring. Care work is still women’s work and as such unequally distributed along gender lines (41), as the following quote demonstrates: “My mother has so many children…and now there is only one” (focus group, family carers, 651 et seq.). In reality, these issues of a just distribution of care work, as they emerged in our findings, seem to be rarely discussed within families (and beyond). The social care role is normally ascribed and assumed without explicit awareness. It is taken for granted. It is, therefore, particularly important to establish, inter alia, a neutral facilitation of family discussions (see Table 5: “moderating care arrangements”). Another social and political issue associated with power relations and serious asymmetries concerns dealing with bureaucracy—a situation, in which people in an existential crisis are confronted with, at worst, standardized, cold and unresponsive procedures (see Table 5: “vicariously organizing care”). Our research confirms the necessity of considerations on how to integrate principles from care ethics, like attentiveness for individuality and particular situations as well as fostering relational decision-making (“discretion”) within bureaucratic organizations, which necessarily operate on the basis of general rules and technical jargon (27). Our research also confirms Avishai Margalits famous claim for a “decent society” (43), as a society that does not humiliate, or more precisely, a society whose institutions do not humiliate people dependent on them.

Maintaining the “critical” potential of caring communities

Our findings on the “ingredients” of a care web describe dimensions at the community level which supports the relationship of direct care. It became clear, that practices on this level are deeply influenced and determined by social and political conditions. Hence, at the international expert workshop we, inter alia, reflected socio-political dimensions of citizen-led community care. On the level of society, caring community initiatives were interpreted by the participants as counter movement to problematic aspects of individualism in modern societies. The discussion marked the critical potential of caring communities, which could be considered for prospective developments. The following aspects seems to us of particularly value:

Resistance to the commercialization and fragmentation of care

On the level of the organization of care, caring communities are seen as the reaction to the fragmentation, specialization and commercialization of care practices. Thus, caring community developments should be aware of their political significance. They should maintain this critical potential and therefore not legitimize themselves politically as cost-saving, economic measure.

Resistance to the privatization of care

Caring community initiatives should be alert to the privatization of care in the sense of delegating and pushing back care responsibilities into private spheres. This effectively means that care responsibilities would rest once more on the shoulders of womankind. Additionally, caring communities should not evolve to a—cost saving - volunteer model of care, replacing absolutely needed professional structures and its public financing.

Resistance to dynamics of disempowerment in communities: bonding and conformism

Caring communities create novel forms of social ties and compassion in the, according to Klaus Dörner (44)—“third social space”, between private households and institutionally-provided care. Thus, the proper sphere in which to learn empathy, attentiveness and care might be seen in the neighbourhood (and less in the spheres of family or friendship), since neighbours are to some extent unfamiliar, so that the circle of caring has to be extended—but at the same time close enough to care to care. As our data show (see Table 5, “keeping an eye on each other”), neighbours—in this sense—are not engaged in everyday care and are not deeply involved in intimate care relationships and as dialogue partners for the exchange of life wisdom, yet they can offer small gestures of help that sometimes make a great difference, not least on a symbolical level regarding attentiveness in everyday social life. In order to encourage this neighbourhood-based care culture in communities, it is, as a first step, necessary to acknowledge the social diversity of neighbourhoods and communities; and also to see the potentially negative side effects of rigid bonding communities; such as social exclusion or disadvantages resulting from all too tightly-knit communities with alleged unity (45). Thus, the challenge and “art” of being a good neighbour includes strengthening the qualities of bridging in the community, which means in particular, showing openness for the unknown, the stranger, who lives next door or in the next street.

Conclusions

In his famous diagnosis of the modern world in “The ethics of authenticity” (46), Charles Taylor describes “individualism” and the “predominance of instrumental reason” as main categories of the “malaise of modernity”. The predominance of instrumental reason “makes us believe that we should seek technological solutions even when something very different is called for” (46). Concerning individualism he indicated, that of course only “few people want to go back on this achievement” (46) but at the same time “many of us are also ambivalent” as individualism seems to be associated with new forms of uncertainty, that arise out of, for example, the partial loss of social connections and of purpose and meaning in life (46). As for the future and current developments, we would like to reflect briefly upon our results from this broader point of view.

First, Taylor’s remarks on the predominance of instrumental reason should be taken seriously in health-promoting strategies or civil society-oriented end-of-life care in order to rebalance a partnership of two aspects of end-of-life care that are essential—the professional service and the community/civic, as well as to avoid too simplistic and uncritical approaches in the development of caring communities. Following David Buchanan (47), the modern health-promotion is still marked by the predominance of instrumental reason. Health-promotion interventions seek to change attitudes, behaviour and circumstances—and the success of interventions is measured or evaluated by various indicators of (a change of) health status. It seems to us morally dubious to influence attitudes, behaviour and circumstances by methods whose strength is to predict and to control. At worst, a simple orientation via a health status indicator model and effective behaviour change methods “undermines the most fundamental understanding of ethical human relationship” (47). Caring communities as a collective social learning process should enable, according to Buchanan, “[…] the artful practice of open-ended questioning to allow the learner to discover, rather than be told, the personal meaning of life experiences.” (47). Therefore, prospective caring community progresses need (I) an ecological health-promotion framework for action (19) and (II) collective social learning processes along the existential experiences and the wisdom of community members, complementing one another.

Second, caring community initiatives can also be seen, in principle, as a movement counter-balancing the negative effects of modern individualism and the persistent tendency in modern societies to subject the organisation of care too much to the logic of the market. However, we also notice a necessity not to “romanticize” communities. In our project, it became apparent that that the spheres of private life and of the community are influenced by social and cultural conditions—and any idealization of the “community” leads to obscure unfair distribution of care responsibilities, social exclusion and diversity. The caring community movement and public health end-of-life care, therefore, needs to maintain its intrinsic critical potential at political level. Charles Taylor expresses his intuition that instrumental reason and individualism could be informed “by an ethic of caring” (46). In our view, the findings describe some of the conditions and prerequisites of such a fundamental ethic of caring in practice on a community level. Co-creating supportive care relationships in the local care web, through an ongoing cultivation of its “ingredients”, as well as enabling and organizing existential-political care dialogues (40) are measures that could initiate and facilitate a caring community.

Acknowledgements

First and foremost we thank all family caregivers, volunteers and other participants in this research for taking time and sharing their experiences and wisdom. We thank the participants of the international expert workshop for sharing their expertise. Particular thanks to our colleagues Nathalie Schwaiger, for her feedback on the paper and proof reading, and Sonja Prieth, for her major contribution to the research process. This work was supported by the Association for the Promotion of Science and Humanities in Germany, the Tyrolean Hospice Association, the municipality Landeck, and the Austrian Red Cross.

Footnote

Conflicts of Interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- Elias N. The Loneliness of the Dying. Blackwell, Oxford, 1982.

- Kellehear A. A social history of dying. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2007:253.

- Conradi E, Vosman F. Praxis der Achtsamkeit: Schlüsselbegriffe der Care-Ethik. Frankfurt: Campus Verlag, 2016.

- Sander-Staudt M. The unhappy marriage of care ethics and virtue ethics. Hypatia 2006;21:21-39. [Crossref]

- Leonard R, Horsfall D, Noonan K. Identifying changes in the support networks of end-of-life carers using social network analysis. BMJ Support Palliat Care 2015;5:153-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Saunders C. The philosophy of terminal cancer care. Ann Acad Med Singapore 1987;16:151-4. [PubMed]

- Sepúlveda C, Marlin A, Yoshida T, et al. Palliative care: the World Health Organization's global perspective. J Pain Symptom Manage 2002;24:91-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Centeno C, Lynch T, Garralda E, et al. Coverage and development of specialist palliative care services across the World Health Organization European Region (2005–2012): Results from a European Association for Palliative Care Task Force survey of 53 Countries. Palliat Med 2016;30:351-62. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Sallnow L, Kumar S, Kellehear A. International perspectives on public health and palliative care. London: Routledge, 2012.

- World Health Organization. Ottawa charter for health promotion. First International Health Promotion Conference, Canada: Ottawa, 1986.

- Kellehear A. Health-promoting palliative care: developing a social model for practice. Mortality 1999;4:75-82. [Crossref]

- Kellehear A. Compassionate cities. London: Routledge, 2005.

- Sallnow L, Richardson H, Murray SA, et al. The impact of a new public health approach to end-of-life care: A systematic review. Palliat Med 2016;30:200-11. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Wegleitner K, Heimerl K, Kellehear A. Compassionate Communities. Case studies from Britain and Europe. New York: Routledge, 2016.

- McLoughlin K, Rhatigan J, McGilloway S, et al. INSPIRE (INvestigating Social and PractIcal suppoRts at the End of life): Pilot randomised trial of a community social and practical support intervention for adults with life-limiting illness. BMC Palliat Care 2015;14:65. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Horsfall D, Yardley A, Leonard R, et al. End of life at home: co-creating an ecology of care. Penrith, N.S.W, Western Sydney University, 2015. Available online: http://researchdirect.uws.edu.au/islandora/object/uws%3A32200

- Noonan K, Horsfall D, Leonard R, et al. Developing death literacy. Prog Palliat Care 2016;24:31-5. [Crossref]

- Kellehear A. Health-promoting palliative care: developing a social model for practice. Mortality 1999;4:75-82. [Crossref]

- Kellehear A. The Compassionate City Charter: inviting the cultural and social sectors into end of life care. 2015. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/283822073_The_Compassionate_City_Charter_Inviting_the_cultural_and_social_sectors_into_end_of_life_care

- Rosenberg JP, Mills J, Rumbold B. Putting the ‘public’ into public health: community engagement in palliative and end of life care. Prog Palliat Care 2016;24:1-3. [Crossref]

- Riffin C, Kenien C, Ghesquiere A, et al. Community-based participatory research: understanding a promising approach to addressing knowledge gaps in palliative care. Ann Palliat Med 2016;5:218-24. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Minkler M, Wallerstein N. Community-Based Participatory Research for Health. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 2003.

- Maiter S, Simich L, Jacobson N, et al. Reciprocity: An ethic for community-based participatory action research. Action Res 2008;6:305-25. [Crossref]

- Bührmann AD, Schneider W. Vom Diskurs zum Dispositiv: Eine Einführung in die Dispositivanalyse. transcript Verlag, Bielefeld, 2015.

- Wegleitner K, Schuchter P, Prieth S. ‘Ingredients’ of a supportive web of caring relationships at the end of life. Sociol Health Illn 2018. [Epub ahead of print]. [Crossref]

- Rehnsfeldt A, Eriksson K. The progression of suffering implies alleviated suffering. Scand J Caring Sci 2004;18:264-72. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bourgault S. Prolegomena to a caring bureaucracy. Eur J Women’s Studies 2017;24:202-17. [Crossref]

- Kübler-Ross E, Wessler S, Avioli LV. On death and dying. JAMA 1972;221:174-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bourgault S. Attentive listening and care in a neoliberal era: Weilian insights for hurried times. Etica Politica 2016;18:311-37.

- Wallerstein N. Powerlessness, empowerment and health: Implications for health promotion programs. Am J Health Promot 1992;6:197-205. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Wallerstein N, Duran B. Community-based participatory research contributions to intervention research: the intersection of science and practice to improve health equity. Am J Public Health 2010;100:S40-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Sallnow L, Tishelman C, Lindqvist O, et al. Research in public health and end-of-life care–Building on the past and developing the new. Prog Palliat Care 2016;24:25-30. [Crossref]

- Clavier C, Sénéchal Y, Vibert S, et al. A theory-based model of translation practices in public health participatory research. Sociol Health Illn 2012;34:791-805. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Frank AW. The wounded storyteller. Body, Iilness, and ethics. Chicago and London: The University of Chicago Press, 1997.

- Hadot P. Exercices spirituels et philosophie antique. Paris: Albin Michel, 2002.

- Jaspers K. Einführung in die Philosophie. Zwölf Radiovorträge. Piper, München/Zürich, 2008.

- Begemann V. Hospiz. Lehr- und Lernort des Lebens. Stuttgart: Kohlhammer, 2006.

- Heller A, Pleschberger S, Fink M, et al. Die Geschichte der Hospizbewegung in Deutschland. Ludwigsburg: Hospiz Verlag, 2012.

- Schuchter P. Sich einen Begriff vom Leiden Anderer machen. Eine Praktische Philosophie der Sorge. Bielefeld: transcript, 2016.

- Schuchter P, Heller A. The Care Dialog: the “ethics of care” approach and its importance for clinical ethics consultation. Med Health Care Philos 2018;21:51-62. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Tronto JC. Caring democracy: Markets, equality, and justice. New York: NYU Press, 2013.

- Tronto JC. Creating caring institutions: Politics, plurality, and purpose. Ethics and social welfare 2010;4:158-71. [Crossref]

- Margalit A. The Decent Society. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1996: 147.

- Dörner K. Leben und sterben, wo ich hingehöre: dritter Sozialraum und neues Hilfesystem. Neumünster: Paranus-Verlag, 2007.

- Vibert S. La communauté est-elle l'espace du don ? De la relation, de la forme et de l'institution sociales (2e partie). Revue du MAUSS 2005;25:339-65. [Crossref]

- Taylor C. The Ethics of Authenticity. London: Harvard University Press, 1991.

- Buchanan DR. An Ethic for Health Promotion. Rethinking the Sources of Human Well Being. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2000.