Patient-centered family meetings in palliative care: a quality improvement project to explore a new model of family meetings with patients and families at the end of life

Introduction

There is some evidence that family meetings in palliative care enhance communication with family members, and identify families’ unmet needs (1,2). While consensus-based guidelines advocate routine family meetings during each admission (1,3), little is known about their implementation in specialist palliative care, or the benefits of family meetings for participants (4). Few studies have examined interactions occurring in family meetings. Furthermore, a small Australian study from one inpatient palliative care unit reported that ‘‘formal’’ family conferences were rarely initiated, especially if the treating team thought the patient’s care was uncomplicated (5). However, when meetings occurred, the agenda was often dominated by issues identified by the team, and patients’ voices were rarely heard. Another study revealed diverse approaches to managing family meetings between different disciplines, and a lack of structured approaches; only 5% of surveyed clinicians followed a defined protocol and 17% invited patients to attend the entire meeting (6). One retrospective study of palliative care family meetings (n=123) documented timing of meetings and topics discussed, who participated, their level of distress, and any conflict (7). The study found that family meetings were held on average three days before discharge, 60% were attended by patients, and few addressed topics related to advance care planning for end of life decisions. An ethnographic study of ad hoc family meetings, not attended by patients, identified clinician and family triggers for organizing family meetings, concluding that there is a need to better understand outcomes for family members (8). There is also little baseline data published regarding frequency and conduct of usual family meetings in the inpatient palliative care setting. No literature documenting a patient-centered approach to family meetings was identified.

Patient-centered care

Patient-centered care is captured in the phrase “No decisions about me, without me (9)” and is characterized by: (I) informing and involving patients; (II) eliciting and respecting patient preferences; (III) engaging patients in the care process; (IV) treating patients with dignity; (V) designing care processes to suit patient needs, not providers; (VI) providing ready access to health information; (VI) facilitating continuity of care (10). Given its emphasis on holistic care, and on supporting both families and patients (11), palliative care philosophies are congruent with a patient-centered approach. Nonetheless, Australian palliative care guidelines for family meetings describe a model where patient and family participation are still largely guided by clinicians (3).

A patient-centered approach to family meetings presents significant challenges, as patients’ symptoms may limit their capacity to participate. Family meetings attended by patients may differ from meetings held for families (7,12), and if patients are present, they may be spoken for and about more than speaking themselves or being spoken to (5,6). Family meeting participants (patients, families, clinicians) may all have different, and sometimes competing, needs and goals. All of these considerations mean that a patient-centered approach to family meetings requires careful evaluation.

A patient-centered paradigm for family meetings

The aim of this quality improvement project was to improve our communication with patients and their families through a new approach of patient-centered palliative care family meetings. This study has adapted existing clinical practice guidelines into a more explicitly patient-centered approach. The purpose of the patient-centered family meeting is to create an opportunity, with no clinician-determined agenda, for newly admitted patients and their chosen family members and supporters to meet the palliative care team, early in their first admission for inpatient palliative care. In our model the clinicians’ task is to facilitate conversations about any issues the patient and/or family identify, assisting them to talk about the future as they wish, and then to hear, acknowledge, and where appropriate respond to patient and family concerns. Whilst patient-centered family meetings were not explicitly designed to be therapeutic, the approach shares some characteristics with other therapeutic interventions in palliative care (i.e., Dignity Therapy, Cancer And Living Meaningfully: CALM), which aim to provide a reflective and supportive space where patients clarify their relationships and legacy, thereby assisting preparation for death (13,14).

Methods

The project was undertaken at a 32-bed public specialist palliative care unit serving the southern region of Sydney, which is a culturally diverse community. This unit provides respite, end-of-life care, symptom management, and/or psychosocial care for patient and/or their families. Admitted patients may also continue to receive active treatment as clinically appropriate, including chemotherapy and radiotherapy.

We developed and manualized a patient-centered family meeting model which was adapted from Australian guidelines (3). “Family” is taken to include caregivers and supporters in close relationships acknowledged by the patient as important to them. The study design and methods were discussed at a concept development workshop attended by palliative care consumers (carers) and palliative care clinicians and researchers. The Research Social Worker subsequently piloted the interview questions with patients (n=10) and incorporated their feedback. We also piloted the feedback questionnaires with family members (n=10) who then provided feedback about the meeting. A focus group was also held with staff to obtain meeting feedback.

A 60-minute patient-centered family meeting was offered routinely within seven days of admission, and scheduled at a mutually convenient time as soon after admission as possible. Patients admitted for the first time for inpatient palliative care between 30th May 2012 and 30th June 2013 were eligible if they were: (I) over 18 years of age; (II) physically and cognitively able to consent and participate in a family meeting; (III) their family or friends were able to participate in a family meeting (face to face or by phone). Exclusion criteria were (I) a cognitive impairment; (II) actively dying or (III) unable to nominate participants for a family meeting. During the project, the presence/strong suspicion of abuse or familial violence affecting the patient’s key relationships was identified as an additional exclusion criterion. Family members or carers identified by the patient for participation were eligible if they were: (I) over 14 years of age; (II) physically and cognitively able to participate in a family meeting; and (III) consented to provide feedback. Family members who did not consent to provide feedback could still attend the family meeting.

Eligible patients were given information and consent forms, and invited to participate in the study by the Research Social Worker. They received a Patient Booklet to help them prepare for the meeting. The booklet contained the following questions to assist in forming an agenda for the meeting: (I) what are you expectations of the admission? (II) who is affected by your illness? (III) are you at peace? (IV) how do you see your health problems at the moment? (V) do you have any concerns about what is happening to you? (VI) what help would you like? (VII) what the staff really need to know about me.

The patient could choose to self-complete, or request the Research Social Worker’s help. After completing the Patient Booklet, the Research Social Worker asked participants who they wished to invite to the meeting, what they would like to discuss, and whether they wished to attend all, some, or none of the meeting. All non-English speaking background patients participating in patient-centered family meetings were offered an interpreter. A private space was used, ideally located away from patient areas of the ward, or in patients’ private rooms. If the patient agreed, information provided in the booklet and during the intervention meeting was subsequently made available to their treating team.

After the meeting, the clinician leading the meeting documented goals of care and other key elements from the discussion on standard forms used by the Local Health District for family meetings. Copies were provided to the patient, and placed in the clinical record and the research file.

Data collection and analysis

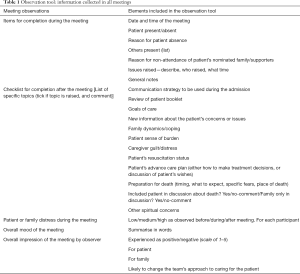

The Research Social Worker observing the patient-centered family meetings populated a case report form including basic participant demographic and clinical information. This Researcher also collected field notes using a structured Observation Tool (Table 1) developed specifically for this project as no validated measures were identified that could adequately capture the detail of these meetings. The Observation Tool included: standardized and detailed descriptions of the meeting, participants, their interactions and observed distress, and topics covered. It was decided not to audio-record meetings because of the difficulty of capturing and transcribing discussions between multiple participants, and the need to study behaviors within a potentially large group. After each meeting, the Research Social Worker distributed family feedback questionnaires to consenting family participants. This included demographic information, relationship to patient and feedback on meeting processes. Patients who were well enough in the week following the interview were briefly interviewed to assess the acceptability of the meeting for them.

Full table

Numeric data were analyzed with descriptive statistics using SPSS version 23.

Recruitment rates, number, and timing of family meetings were documented to assist in designing a future study. Qualitative data collected with the Observation Tool, Patient Interviews and Focus Group were analyzed using the constant comparison method (15). Data were coded independently by three coders (CR Sanderson, A Johnson, EA Lobb) to identify the main focus of each meeting, interview, and focus group and the emerging themes compared and agreed on. Data collected with the Observation Tool allowed documentation of themes being discussed, by whom issues were raised, and the time spent discussing each issue. The Tool recorded an assessment of how distressed patients and participants appeared before, during and after the meeting as high, moderate, or low, based on observations of verbal and non-verbal behaviors.

Ethical considerations

The study was approved as a Low Risk Study by Prince of Wales Hospital Human Research Ethics Committee (HREC) (approval number 12/220 LNR/12/POWH/417) and Calvary Health Care Kogarah HREC. Ethics approval was obtained to include children aged 14 and over, acknowledging that they also provide care and may wish to participate. Potential conflicts of interest for the lead investigator who developed the intervention were addressed by establishing a project steering group, including heads of the disciplines involved in family meetings, and senior researchers not clinically involved in patient care. They oversaw the study and implementation of the patient-centered family meeting project.

Results

Participant characteristics

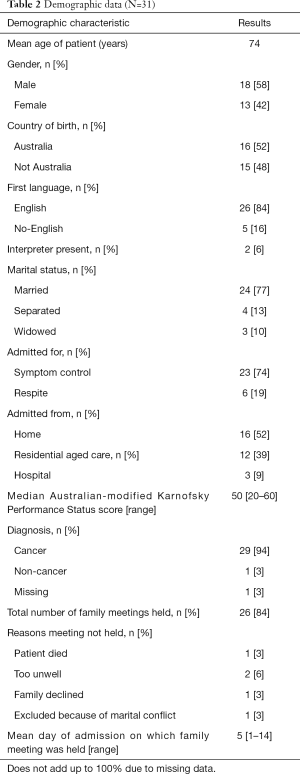

A total of 31 patients were identified to participate in a patient-centered family meeting, out of a screened population of 250 patients and 26 patient-centered family meetings were held. One patient was excluded after recruitment, when the team became aware of concerns about domestic violence, and considered that a family meeting would be inappropriate. The mean age was 74, SD 13.4 (range, 49–92) years. Almost half of the patients (48%) were born in countries other than Australia with 84% having English as their first language and 6% requiring an interpreter. The majority were married (77%) were admitted for symptom control (74%) and had a cancer diagnosis (94%) (Table 2).

Full table

Characteristics of the family meetings

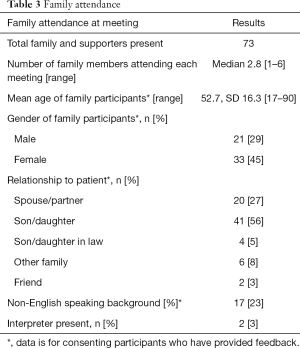

Patient-centered family meetings were generally held within the first week of the admission [mean of day 5, SD 2.1 (range 1–14)]. Patient-centered family meetings were attended on average by 25 patients and involved a cross-section of patients’ family networks (totaling 73 persons). The median number of family members attending each meeting was 2.8, SD 1.3 (range 1–6). The demographics of family in attendance are reported in Table 3.

Full table

Themes and content of the family meetings

Thematic analysis generated from data captured in the meetings using the Observation Tool identified that the conversations clustered around three content themes (Table 4).

Full table

- Information/problem focus: related to specific symptoms and how these would be managed, discussion of treatment options, practicalities of discharge planning, and the support needed by either the patient or their caregivers;

- Family focus: related to understanding the patient in the context of their family and the story of their relationships, history, and approach to dealing with their current illness, including any concerns about how the illness affects different members of the patient’s network;

- End of life focus: related to discussing whether a patient was in or close to the terminal phase of their illness, changing goals of treatment because of short prognosis, discussing the care that would be provided at this time, and explaining what to expect during the dying process.

A family focus was most common (54%) in patient-centered meetings. End of life issues were commonly (69%) raised in patient-centered meetings, and with one exception the patient was present. Table 4 provides more detailed information about issues that were discussed in meetings.

The proportion of meeting time spent on issues raised by the team, family and patient was estimated based on times recorded in the Observation Tool. These showed: the mean patient-centered meeting time was 37.5 minutes long (range, 10–66 minutes); 47% of meeting time was focused on issues raised by the team; 39% issues were raised by the family; and 13% of issues were raised by the patient. Whilst the total time spent on issues raised by patients was small, 60% of patients did raise an issue. In all patient-centered meetings, new information that affected how the team cared for the patient was contributed, based on an assessment by team members after the meeting.

Patient experience of the meetings

Patients in the patient-centered meeting group who were well enough gave feedback in a brief interview after the family meeting (n=20). The majority of those interviewed (n=19) found the meetings useful describing it as “constructive”, “inspiring”, “fruitful”, “open and interesting”, “rewarding.” One participant described it as “boring” as “it was just the same old stuff.”

“It was—it was useful from the point of view that everybody knew what—you know, about the situation – like as in there was no need to go over again, everybody like was there and everybody knew exactly what—what it was all about and everybody— everything was in the open sort of”. (Male patient)

They perceived the main themes were a discussion of medical status; quality of life; coping; expectations for the future; how the family is responding; what support is available; and what the future may hold.

“The main things were about how our family’s responding, how [Name] and I were responding, how coping and what we might need help with, starting to think about what we might need help with. And financial things as well as emotional things, medical things”. (Female patient)

The majority (n=23) did not find the meeting distressing because they were resigned to or had accepted their situation; or had held previous conversations with family members and acknowledged the importance of “getting things out in the open” in “an honest and direct way”.

“I know there is no cure, there is no hope as much—it’s only a matter of time, so there’s nothing, nothing new. Nothing upsetting I mean I’m not with it. Obviously, but that’s the way it is and – so I am aware of the fact that I’m going to die so that’s the way it is”. (Male patient)

However, several patients found distressing the discussion held in front of their family about leaving their loved ones and their death.

“Yes, telling people you want to die—I don’t think you can get much more distressing than that. Talking in front of any people, I mean in front of my youngest son. Not fun. My wife, not fun”. (Male patient)

Participants also reported feeling “good”; “more settled’ “relaxed”; “confident”; “comfortable”; “relieved” as a result of the meeting.

“I felt a little bit more relieved by the way—I know NAME—sort of I can handle it a little bit more, better than I can—more than she can because she gets too emotional too quick”. (Male patient)

Most felt the meeting covered what they wished to talk about.

“No it’s good to get it all out in the open. Now I know what’s going on and I’m fine with it”. (Female patient)

The majority reported that those family members who they wanted to come to the meeting were there and there were no reports of people present who they did not want at the meeting. For those who did not have all the people they wanted present, reasons for non-attendance included working and living too far away.

All the participants reported that the meeting was helpful for themselves and their family. The themes that emerged were “bringing things out in the open”; “everyone being there to hear the same message”; to formulate plans; an opportunity to express opinions and ask questions; to have clarity about what was happening.

There were no patient suggestions for improving the meeting with the majority finding the meetings “well organized”; “constructive”; “practical as well as emotional” and “spot on”.

The majority of patients reported (n=15) that they were at peace, with five reporting they were not. A sense of peace was described as “knowing what will happen”; “accepting their situation”; “reflecting on having lived a good life”; “receiving good care”; “having family and friends” and “having information about their situation”. Not being at peace was associated with “physical symptoms”; “uncertainty”; “lack of control”.

“Oh yes, I am…won’t say that I am happy with the situation but yes I am not, I’m not angry with the world or I’m not thinking or saying “why me” or I’m not I’m not upset about it in the sense that I accept the fact that for one reason I’m finished up, incurable cancer and because medical science can’t cure it at this stage, the end is going to be what it’s going to be, that’s it. There’s no way out, so I know that yeah”. (Male patient)

Family experience of the meetings

The majority of family members reported that the invitation to the meeting was perceived as “not at all” distressing (84%); reassuring (77%); not worrying (86%) and helpful (83%). However, a few family members (8%) found it “very distressing”; almost a quarter (23%) was not reassured by the invitation; 13% found it worrying and not at all helpful (16%). Similarly the majority found attendance not upsetting (87%). Importantly 92% of family members found the meeting reassuring and 95% found it helpful. Almost a quarter found the meeting worrying (23%).

Staff experience of family meetings

A focus group was held with palliative care pastoral care and social work staff (n=10) who had attended the meetings. The overall feedback was positive. A key outcome for the staff was the ability to have psycho-social information on the patient and family early in the admission. A social worker commented that it would have taken several meetings to obtain the information that the single patient-centered meeting provided and of the significance to “see everyone on the same page.”

“This meeting helps people be informed, reassuring. I think you made more of a connection with the person, had a bit more in common, trusting. What a link to provide this opportunity, felt quite a connection, they were pleased to see you”. (Pastoral Care worker)

Staff commented that “there were many tears” and found the meetings “very moving” but did not see this distress as detrimental as family members and patients were given permission to speak openly.

“They do take it as an opportunity to say farewells in a public arena when well enough to do it. Very empowering”. (Social worker)

The opportunity for issues other than medical concerns to be discussed was seen as another benefit of the patient-centered meetings. The importance of following an agenda that was not driven by health professional and an opportunity for the patient and family members to be heard by the whole team was highlighted.

“Very different—moved it to a family agenda. We focused on different information. The people present were being heard… There were many tears, they were hard, but they felt part of the process. People had a chance to speak up. When they (family) came in at that (early) stage it was better. Provides an opportunity to address things straight away, whereas if you wait 2 weeks things build up. Reassuring at an early stage.” (Pastoral care worker)

Staff provided feedback that 40 minutes was sufficient time for the meetings as patients tired easily. Social workers reported that it took more time to organize the meeting as they had to contact family members several times to set a time for the meeting when all could attend and to co-ordinate the meeting with a time when the patient was well-enough to participate. Some of the staff felt this was balanced by the amount of information about the patient and family that was able to be obtained in just the one meeting.

“It is more time consuming, pressure on extra work load, but it was worthwhile, probably got more out of it”. (Pastoral care worker)

Feedback about family involvement in the meeting included: providing an opportunity to meet the palliative care team; an opportunity to build trust and to provide a supportive environment in which to raise concerns.

“A lot more focus of talking about them as people, a more of “who are you”. Hearing their story was validating”. (Social worker)

Discussion

Testing the patient-centered family meeting approach

The purpose of this study was to explore whether a patient-centered approach to family meetings to enable patients’ own voices to be heard regarding their palliative care is acceptable and feasible, and in particular whether this context can support shared and witnessed conversations about end of life concerns between patients and families. However it is clear that conversations in which patients can engage equally are difficult to achieve: patients’ symptom burden limited their participation; patients spoke less than either staff or family members. Nonetheless they were present and able to initiate topics of discussion. Overall, staff initiated more topics and it is possible that staff acted as facilitators for patients’ participation, based on their access to the information completed prior to the meeting. Some patients and families may also be unfamiliar with the concept of a meeting where they can lead the agenda.

Understanding what constitutes “patient-centeredness” at this point in patients’ lives is challenging. For frail, ill or fatigued patients, equal participation may be an unrealistic or over-simplistic goal. What counts as meaningful participation will differ. For patients, their presence and centrality to conversations about them may be the key. Our brief interviews supported this, although capturing direct feedback from patients is also challenging at this time; many are clinically deteriorating and very symptomatic. Future studies should identify appropriate low-burden tools to assess the value of these meetings for patients.

In contrast, a recurring theme of those patient-centered meetings with a predominant family focus was that of patients and families expressing their care and concern for each other. For staff attending, these exchanges were sometimes extremely moving. Patient-centered meetings appeared to give participants opportunities to openly acknowledge that the patient would die soon, but the meetings did not require them to make treatment decisions or respond to new clinical information at that time. The experience of these meetings suggests that such conversations, occurring when the patient’s death is approaching and families can talk if they wish and are able to, could potentially help patients and families prepare for death.

Patients participating in patient-centered family meetings were not thought to be imminently dying at the time of recruitment, and the meetings had no clinician-defined agenda. Any discussion related to end-of-life care was raised voluntarily by patients or families. These results suggest that when supported by the palliative care team, many patients and families can openly discuss the patient’s impending death, and many (but not all) will voluntarily do so if given that opportunity.

Distress and family meetings

Patient-centered family meetings were upsetting for some. The presence of some distress is not surprising. However, if family meetings are considered as short-term interventions for information exchange, care planning, or solving immediate problems, distress may be regarded as less acceptable than if they are thought to have longer-term potential benefits for participants. Family meetings ideally provide a setting where distress and emotion can be safely supported by skillful, experienced and knowledgeable clinicians. Being unprepared for a death is a risk factor for complicated grief (16). Participating in a family meeting where emotional and existential concerns are openly discussed, and shared and witnessed conversations with the patient about their end-of-life concerns occur, might potentially provide protection from future bereavement difficulties. Hence the significance of distress expressed in family meetings deserves further study. Longitudinal follow-up would help to understand positive and negative implications.

Limitations

Our findings reflect the setting of care and approaches of the small number of individual clinicians involved in these family meetings. Whilst the meetings were manualized for consistency, a larger study is required to learn if the intervention is sufficiently robust to implement in varied settings, and to explore patient and health service outcomes.

In future studies video recording should be considered so multiple coders can review meeting content. Video-recording may also counter-balance the subjective nature of observations. Interviews with patients a few days after family meetings provided little data; patients were frequently much sicker than in the family meeting, and unable to participate much in this interview. In future studies, follow-up patient interviews should be completed as soon as possible after the meeting.

Conclusions

This study has evaluated a new approach to family meetings, using a patient-centered model. Developing a patient-centered approach to family meetings is feasible and acceptable, and results in a different kind of meeting from standard family meetings. This patient-centered family meeting model includes active involvement of the patient to the extent that they are able to contribute, allowing them to identify who they wish to be present, and what is discussed. This approach can provide valuable opportunities for patients and their families to have shared conversations about end-of-life and family concerns.

Future projects should identify measures that more sensitively respond to patient and family well-being in the end-of-life context, and capture the element of preparation for death. Such measures could be used to evaluate the impact of patient-centered family meetings on end-of-life issues. Long-term impacts on participants during bereavement will also be important to explore.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank patients and staff at Calvary Health Care Kogarah for their support of, and participation in, this project. Additional thanks are due to Professor Liz Forbat for providing helpful comments on the manuscript.

This work was supported by a Cancer Institute New South Wales Reporting for Better Cancer Outcomes (RBCO) Quality Improvement Grant.

Footnote

Conflicts of Interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The study was approved as a Low Risk Study by Prince of Wales Hospital Human Research Ethics Committee (HREC) (approval number 12/220 LNR/12/POWH/417) and Calvary Health Care Kogarah HREC and written informed consent was obtained from all the participants.

References

- Hudson P, Thomas T, Quinn K, et al. Family meetings in palliative care: are they effective? Palliat Med 2009;23:150-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hannon B, O'Reilly V, Bennett K, et al. Meeting the family: measuring effectiveness of family meetings in a specialist inpatient palliative care unit. Palliat Support Care 2012;10:43-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hudson P, Quinn K, O'Hanlon B, et al. Family meetings in palliative care: Multidisciplinary clinical practice guidelines. BMC Palliat Care 2008;7:12. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Cahill PJ, Lobb EA, Sanderson CR, et al. What is the evidence for conducting palliative care family meetings? A systematic review. Palliat Med 2017;31:197-211. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Tobin B, Lobb E, Roper E, et al. Is the patient's voice under-heard in family conferences in palliative care? A question from Sydney, Australia. J Pain Symptom Manage 2011;41:e3-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Rhondali W, Dev R, Barbaret C, et al. Family conferences in palliative care: a survey of health care providers in France. J Pain Symptom Manage 2014;48:1117-24. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Yennurajalingam S, Dev R, Lockey M, et al. Characteristics of family conferences in a palliative care unit at a comprehensive cancer center. J Palliat Med 2008;11:1208-11. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Meeker MA, Waldrop DP, Seo JY. Examining family meetings at end of life: The model of practice in a hospice inpatient unit. Palliat Support Care 2015;13:1283-91. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Coulter A, Collins A. Making shared decision-making a reality. No decision about me, without me. London: The King's Fund, Foundation for Informed Decision Making, 2011.

- Robb G, Seddon M. Quality improvement in New Zealand healthcare. Part 6: keeping the patient front and centre to improve healthcare quality. N Z Med J 2006;119:U2174. [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. WHO definition of palliative care. Available online: (accessed 20.01.16).http://www.who.int/cancer/palliative/definition/en/

- Dev R, Coulson L, Del Fabbro E, et al. A prospective study of family conferences: effects of patient presence on emotional expression and end-of-life discussions. J Pain Symptom Manage 2013;46:536-45. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Chochinov HM, McClement S, Hack T, et al. Eliciting personhood within clinical practice: effects on patients, families and health care providers. J Pain Symptom Manage 2015;49:974-80.e2. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lo C, Hales S, Jung J, et al. Managing Cancer And Living Meaningfully (CALM): Phase 2 trial of a brief individual psychotherapy for patients with advanced cancer. Palliat Med 2014;28:234-42. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Corbin JM, Strauss AL. Basics of Qualitative Research; techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory, 3rd ed. NY: Sage Publications, 2008.

- Lobb EA, Kristjanson LJ, Aoun SM, et al. Predictors of complicated grief: a systematic review of empirical studies. Death Stud 2010;34:673-98. [Crossref] [PubMed]