Abstract

Background:

The early relationships between infant and care takers are significant and the emotional interactions of these relationships play an important role in forming personality and adulthood relationships.Objectives:

The current study aimed to investigate the relationship of attachment styles (AS) and emotional intelligence (EI) with marital satisfaction (MS).Materials and Methods:

In this cross-sectional research, 450 married people (226 male, 224 female) were selected using multistage sampling method in Mashhad, Iran, in 2011. Subjects completed the attachment styles questionnaire (ASQ), Bar-On emotional quotient inventory (EQ-i) and Enrich marital satisfaction questionnaire.Results:

The results indicated that secure attachment style has positive significant relationship with marital satisfaction (r = 0.609, P < 0.001), also avoidant attachment style and ambivalent attachment style have negative significant relationship with marital satisfaction (r = -0.446, r = -0.564) (P < 0.001). Also, attachment styles can significantly predict marital satisfaction (P < 0.001). Therefore, emotional intelligence and its components have positive significant relationship with marital satisfaction; thus, emotional intelligence and intrapersonal, adaptability and general mood components can significantly predict marital satisfaction (P < 0.001). But, interpersonal and stress management components cannot significantly predict marital satisfaction (P > 0.05).Conclusions:

According to the obtained results, attachment styles and emotional intelligence are the key factors in marital satisfaction that decrease marital disagreement and increase the positive interactions of the couples.Keywords

Attachment Styles Emotional Intelligence Marital Satisfaction

1. Background

Attachment theory was first introduced by Bowlby as a primary need (1-4). According to this theory, babies express a combination of innate attachment behaviors like crying, laughing, sucking and grasping and the general reason for such behaviors is maintaining physical nearness with the main attachment side and results in baby’s survival in possible environmental dangers (5). Following the Bowlby theory, Ainsworth, Blehar, Waters and Wall as cited from Olderbak (6), invented strange situation methodology and described three styles of attachment as secure, avoidant and ambivalent. The key concept in attachment theory which describes relationship between baby and parents attachment relationships quality is internal working models (IWM) concept. From attachment theory point of view, children form their IWM through interaction with their caregivers and that is a kind of internalized cognitive representation of the meaning, function and value of social communications (7, 8). In other words, IWMs are formed based on children’s experiences on parents’ responses in the first few years after birth. These models provide rules for attachment behaviors including emotional and cognitive components and organization of beliefs concerning self-worth and acceptance or rejection of parents (9). According to attachment theory, personality and friendly communications are affected directly by IWMs which include romantic relationships and marriage. Hazan and Shaver (10) extended attachment theory to adults’ romantic relationships and romantic love and proved that the personal differences of adults’ attachment styles are similar to those of childhood attachment differences.

On the other hands, current trends of marriage and divorce indicate the importance of emotional intelligence (11). It is a construct in psychology which received attention in general and specialized areas (12). From applied viewpoint, theorists believe that elements of emotional intelligence such as emotions perceive regulation of emotional states and application of emotional awareness are related to psychological adaptation, success and satisfaction with life (13). Marriage is naturally rich in emotion and excitement, and marital happiness is related to identification ability, understanding and true perception of oneself and others. In general, satisfaction with marital relationship is the outcome of a combination of positive and negative emotions which is experienced by couples in common. Fitness (14) believes that emotional intelligence or at least some of its aspects can enrich a marriage with satisfaction and adaptation. He believes that ability to understand and accept other side emotions and thoughts in marital life can result in satisfaction. In fact, there is a clear relationship between abilities, which comprise emotional intelligence, and abilities, which are necessary for successful marital interactions and conversations.

Therefore, since the influence of adults attachment styles (AS) on controlling social communications and satisfied and unsatisfied marital communications are the result of IWMs, which is a cognitive concept, and considering the fact that emotional intelligence concept indicates the latest advancements in relationship between emotion and cognition (15), the present research tried to investigate the relationship between attachment styles and emotional intelligence with marital satisfaction.

2. Objectives

Considering the importance of marital satisfaction among married individuals, the present study aimed to determine the role of attachment styles and emotional intelligence in marital satisfaction.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Participants

The research was a cross-sectional study. Statistical population of the present research included all married people in Mashhad, Iran, who had married at least one year before research time in 2011. According to the census conducted in 2006, Mashhad population was 2427316 which 1223838 (50.41%) were male and 1203478 (49.59%) were female (16). Krejcie-Morgan table was used to calculate sample size (17). Sample size was estimated to be 384 people. Multi-step random sampling method was used to select the sample. First, six out of thirteen districts of Mashhad were selected by random sampling method. Then, streets, lanes and houses were selected randomly and questionnaires were distributed among families. Respondents were provided with personal information questionnaire, Simpson attachment styles questionnaire, emotional quotient inventory (EQ-i) questionnaire and the Enrich marital satisfaction (MS) questionnaire; 530 questionnaires were returned and 450 questionnaires were completed and selected for analysis.

3.2. Rating Scales

3.2.1. Bar-on Emotional Quotient Inventory

The EQ-i is the first valid super-cultural questionnaire used to measure emotional intelligence (EI) and was designed by Bar-on in 1997 (18). It consists of 133 short questions based on a 5-point Likert scale. It has five dimensions and fifteen sub-dimensions. Very high and very low points were rare and most respondents were close to 100. A point over 100 shows that the respondent has a high level of EI and a point below 100 shows that emotional skills in the respondent should be improved. In Bar-on test (18, 19), retest coefficients were 0.85 after one month and 0.75 after four months. Further, internal consistency was measured by Cronbach’s alpha in seven samples of different populations. It ranged from 0.69 (for social responsibility) to 0.86 (self-regard) with an average of 0.76. This questionnaire was normalized for Iranian students (20, 21) and the number of questions was reduced to 90. Cronbach’s alpha coefficient was 0.74 in male students and 0.68 in female students and 0.93 for all respondents. In the present research, Cronbach’s alpha was 0.95. Studies which measured EQ-i with other valid tools mentioned a high validity coefficient (22). The current study used the 90-question questionnaire.

3.2.2. Enrich Marital Satisfaction Questionnaire

This questionnaire was designed by Olson et al. (23). The primary form of this questionnaire contained 115 questions and 12 dimensions. Except for the first dimension which has 5 questions, other dimensions have 10 questions. This questionnaire is based on a 5-point Likert scale (answers from 1 to 5). Olson et al., cited from Sanayee, (23) reported the questionnaire reliability as 0.95, calculated by Cronbach’s alpha coefficient. Soleimaniyan (24) designed a 47-item questionnaire. Reliability of this questionnaire was calculated by Cronbach’s alpha coefficient in a group of 11 people (= 0.95). Cronbach's alpha was 0.95 in the present research. The Enrich questionnaire has satisfactory levels of construct and criterion validities. Correlation coefficients between Enrich questionnaire and family satisfaction dimensions range from 0.41 to 0.60. Further, its correlation with life satisfaction dimensions ranges from 0.32 to 0.41 which is a sign of construct validity. All sub-dimensions of the Enrich questionnaire differentiate between satisfied and dissatisfied couples and it shows that the questionnaire has good criterion validity. The current study used the 47-item questionnaire.

3.2.3. Simpson Attachment Styles Questionnaire

This questionnaire was designed based on three famous phrases of Hazan and Shaver (10) and consists of 13 questions based on a Likert scale and respondents should choose one option out of five to answer a question (from completely agree to completely disagree). Out of the 13 questions, five evaluate secure style and eight questions measure avoidant and ambivalent. Reliability of this questionnaire, based on Cronbach’s alpha coefficient and test retest at one week to two years intervals, is estimated 70.0 (24). Reza Zadeh (25) obtained reliability coefficient 0.68 by means of test retest method and using a sample of 25 couples with a time difference of six weeks. Moreover, internal consistency coefficient of the questionnaire was 0.44. Cronbach’s alpha was 0.86 in the present research. Simpson used Rubin love scale and dependency scale -designed by Berscheid and Fei and self-disclosure scale (26) to investigate discriminant validity of the questionnaire. Results proved validity of the questionnaire. For example, correlation coefficient between Rubin love scale and secure attachment style was 0.22, for avoidant attachment style it was -0.22 and for ambivalent attachment style -0.12.

3.3. Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS ver. 17. To analyze data, descriptive measure, Pearson correlation method and multiple regression with enter method were used.

Concerning ethics, the aim of this study was briefly explained to participants, and they were assured about the confidentiality of their personal information; they signed a consent form to participate in the study.

4. Results

In the present research, 226 subjects (50.2%) were male and 224 (49.8%) female. In addition, other demographic characteristics of participants are shown in Table 1. The multiple regression analysis with enter method was used to predict MS based on AS and EI. In addition, to investigate the relationship between the variables, Pearson’s correlation coefficient was used. Table 2 shows that MS had positive and significant relationship with secure attachment style (0.609) and negative significant relationship with avoidant attachment and ambivalent styles (-0.446 and -0.564, respectively) (P < 0.001). Furthermore, EI and its dimensions had positive and significant correlation with MS in P < 0.001 level.

Demographic Characteristics of Participants

| Total, Frequency (%) | Female, Frequency (%) | Male, Frequency (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, y | |||

| 17 - 22 | 38 (8.4) | 23 (10.3) | 15 (6.6) |

| 23 - 28 | 147 (32.7) | 83 (37.2) | 64(28.3) |

| 34 - 29 | 81 (18) | 39 (17.5) | 41 (18.1) |

| 40 - 35 | 77 (17.1) | 27 (12.1) | 50 (22.1) |

| 46 - 41 | 59 (13.1) | 34 (2.15) | 25 (11.1) |

| 52 - 47 | 29 (4.6) | 13 (5.8) | 16 (7.1) |

| 59 - 53 | 19 (4.2) | 4 (1.8) | 15 (6.6) |

| Educational Level | |||

| Elementary | 15 (3.3) | 10 (4.5) | 5 (2.2) |

| Secondary | 31 (6.9) | 12 (5.4) | 19 (8.4) |

| Diploma | 150 (33.3) | 84 (37.5) | 66 (29.2) |

| Associate degree | 58 (9.12) | 21 (9.4) | 37 (16.4) |

| B.Aa | 168 (37.3) | 76 (33.9) | 92 (40.7) |

| M.Ab | 23 (5.1) | 19 (8.5) | 4 (1.8) |

| PhDc | 5 (1.1) | 2 (0.9) | 3 (1.3) |

Correlation Coefficients Between Attachment Styles, Emotional Intelligence and its Components and Marital Satisfaction

Coefficients of the Influence of Attachment Styles, Emotional Intelligence and its Components in Regression Equation

| B | Standard Error | Beta | T | Sig. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Constant | 133.559 | 10.833 | - | 12.329 | 0 S |

| Secure | 2.44 | 0.350 | 0.331 | 8.137 | 0 S |

| Ambivalent | 2.854 | 0.262 | 0.377 | 10.889 | 0 S |

| Avoidant | -1.971 | 0.339 | 0.218 | 5.808 | 0 S |

| EI | 0.797 | 0.120 | 0.412 | 6.614 | 0 S |

| Intrapersonal | 0.725 | 0.269 | 0.155 | 2.693 | 0.007 S |

| Interpersonal | 0.099 | 0.233 | 0.916 | 0.424 | 0.276 NS |

| Adaptability | 0.936 | 0.443 | 0.111 | 2.13 | 0.035 S |

| Stress management | 0.295 | 0.179 | 0.053 | 1.645 | 0.101 NS |

| General mood | 0.682 | 0.544 | 0.154 | 3.090 | 0.002 S |

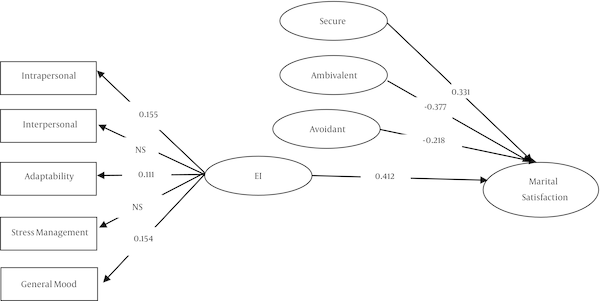

According to the study results, the observed F (F (9, 440) = 66.079) was significant at P < 0.001 and more than 58% of MS variance was explained by attachment and EI (R-squared = 0.584). Regression coefficients of predicting variable showed that attachment styles and EI and intrapersonal, adaptability and general mood dimensions can explain MS variance significantly. In Table 3, regression coefficients of attachment styles (secure = 0.331, ambivalent = -0.377 and avoidant = -0.218), EI (0.412), intrapersonal dimensions (0.155), adaptability (0.111) and general mood (0.154) showed that these variables can predict changes in MS variable. Furthermore, the predicting role of interpersonal and stress management dimensions was not significant (P > 0.05). Figure 1 showed that all predicting variables had significant influence on prediction of MS except for interpersonal and stress management dimensions.

Regression Diagram of variables Which Predict Marital Satisfaction. NS, not significant.

Moreover, side results analysis revealed positive significant relationship between secure attachment style and EI (r = 0.108, P < 0.05) and negative significant relationship between avoidant and ambivalent attachment styles and EI (-0.242 and -0.230, respectively) (P < 0.05).

5. Discussion

Results of the research showed that attachment styles can significantly predict marital satisfaction. Furthermore, MS had positive significant relationship with secure attachment style and significant negative relationship with avoidant and ambivalent styles. These results match with the results of studies conducted by other researchers (10, 27-39). Moreover, regression coefficients of the independent variable showed that general EI and intrapersonal, adaption and general mood can predict MS variance significantly. However, the roles of interpersonal and stress management variables were not significant. Furthermore, Pearson correlation coefficients showed that EI and all its dimensions had positive significant correlation with MS. These results match with those of the studies by Najm (40), Fizser (41), Schutt et al. (42), Mehrabian (43), Vadnais and Michelle (44), Croyle and Waltz (45), Waldinger (46), Thomas and Fletcher (47), Geist and Gilbert (48), Wenzel and Graff (49), and Tirgari (50).

There may be several reasons for such results: self-confidence and trust in others are two attributes of secure individuals (51-53). Self-confidence helps secure individuals with establishing close relationship with others and behaving more tactfully. Trust in others helps secure individuals with having positive attitude towards interactions with others. It is clear that when an individual defines himself/herself and other people positively, he/she is attracted and accepted by people. Therefore, this positive attitude towards oneself and others increases MS. In other words, this attribute provides necessities for a healthy social and psychological communication. In their marital life, such individuals can satisfy their spouse by means of establishment of a healthy communication.

Lack of self-confidence and trust in others are two major attributes of insecure individuals (avoidant and ambivalent) (54, 55). It can be said that lack of self-confidence and trust in others reduces individuals’ ability to interact and associate with others and especially with spouse. Avoiding interpersonal relationships and failure to become friendly with others results in anxiety and inferiority complex in social communications, which increases interpersonal and marital problems and causes negative self-conception. That is to say, it has negative influence on marital life. Another reason may be the fact that an avoidant individual evades establishing relationship with others and avoids a relationship as soon as he/she understands the relationship is becoming closer. Ambivalent individuals tend to associate with other people but they fear from becoming excluded. In addition, ambivalent people desire to be integrated with others but they are afraid of rejection; therefore, they represent interpersonal positions in a more pessimistic way and in comparison with others, consider themselves as less capable of receiving rewards. Ambivalent individuals become distressed in their communications. They avoid other people and are not satisfied with their marital life (56).

Salovey and Mayer, cited from Mayer (15), believe that EI is made up of four basic components: a) perception, evaluation and expression of emotion; b) emotional facilitation of thinking; c) understanding and analysis of emotions, and application of emotional awareness; and d) responsive regulation of emotion to improve emotional and intellectual growth. According to this definition, basic factors involved in EI include perception of emotion in oneself and others and understanding these excitements and management of emotion. Such factors provide an appropriate platform to have a prosperous life. Significance of EI and MS can be due to the above reasons.

Schutt and Mallouff (57) showed that individuals with low level of emotional quotient (EQ) have the following characteristics: lack of self-awareness, lack of understanding of constructive feedbacks, lack of sensitivity to others’ feelings and such individuals use others to satisfy their emotional needs. Such individuals feel they are judged by others, they feel they are not appreciated by other people, and they feel they are abused by others. Individuals who have a high intelligence quotient (IQ), but have a low EQ have many problems in their lives. Such individuals feel they are superior to others and think they are aware of everything while such individuals usually have low recognition of their emotions and feelings. They usually do not understand empathy and sympathy. They always feel they are right because they are intelligent (57, 58). This makes individuals’ approach defensive and reduces empathic feelings in them. This vicious cycle disrupts and destroys individuals’ communications. In short, individuals who have a high level of EQ usually enjoy satisfying individual communications and individuals with a high level of EQ express their feelings politely and non-aggressively. They also understand expressed emotions (59). Goleman (11) believes that EI has an important role in the establishment and stabilization of communications. Saarni (59) supports Goleman’s belief and shows that emotional competency is an important factor in social development and improving the quality of interpersonal communications. Therefore, individuals with high levels of EI are expected to establish social communications and have better communications with other people, one of which is marital relationship (60, 61). The limitation of the present study was that the researchers in cooperation and partnership faced difficulties in the response to the marital satisfaction questionnaire that a number of the questions have sexual nature.

5.1. Suggestions

1. Considering the fact that the results of this research verified the important role of attachment styles in MS, it is recommended to provide consultancy for couples before marriage to reduce high risk marriages and prevent insecure individuals’ marriage; insecure individuals should be identified and treated by psychologists to have happier marriages, prevent incompatibilities and thereby eliminate many family problems.

2. Since attachment styles are formed in childhood, parent-child communications should not be ignored because they affect adulthood communications. Therefore, parents should receive psychological advice during their children’s development to become more aware of their children’s behavior.

3. Since the present research showed that intrapersonal, adaption and general mood dimensions can predict MS significantly, couple-therapy plans and education of EI skills can focus on these variables, although other dimensions also have significant correlation with MS.

Acknowledgements

References

-

1.

Bowlby J. Attachment and Loss. 1. New York: Basic Books; 1969.

-

2.

Bowlby J. Attachment and loss. 2. New York: Basic Books; 1973.

-

3.

Bowlby J. Attachment and loss. 3. New York: Basic Books; 1980.

-

4.

Bowlby J. A secure base: Parent-child attachment and healthy human development. New York: Basic Books; 1988.

-

5.

Granqvist P, Hagekull B. Religiousness and perceived childhood attachment: profiling socialized correspondence and emotional compensation. J Sci Stud Relig. 1999;38:254-73.

-

6.

Olderbak S, Figueredo AJ. Predicting romantic relationship satisfaction from life history strategy. Pers Individ Dif. 2009;46:604-10.

-

7.

Bowlby J. A Secure base: clinical application of attachment theory. London: Routledge; 1988.

-

8.

Obegi JH, Berant E. Attachment theory and research in clinical work with adults. New York: Guilford Press; 2009.

-

9.

Dozois DJ, Frewen DA, Covin R. Cognitive theories. 1. Newjersey: Johen Wiley & Sons, Inc; 2006. p. 173-91.

-

10.

Hazan C, Shaver P. Romantic love conceptualized as an attachment process. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1987;52(3):511-24. [PubMed ID: 3572722].

-

11.

Goleman D. Emotional Intelligence. New York: Bantam Books; 1995.

-

12.

Mohseni N. Theories in development psychology[in Persian]. Tehran, Iran: Pardis; 2004.

-

13.

Pellitteri J. The relationship between emotional intelligence and ego defense mechanisms. J Psychol. 2002;136(2):182-94. [PubMed ID: 12081093].

-

14.

Fitness J. Emotional intelligence and intimate relationship. Philadelphia: Taylor & Francis; 2001. p. 98-112.

-

15.

Mayer JD. A filed guide to emotional intelligence. Philadelphia: Taylor & Francis; 2001. p. 3-24.

-

16.

The population of Mashhad City. 2010. Available from: http://e.mashhad.ir.

-

17.

Khooynejhad G. Research methods in education [in Perian]. Tehran, Iran: Samt; 2008.

-

18.

Bar-On R. Bar-On Emotional Quotient Inventory (EQ-I). Toronto, Canada: Multi-Health Systems; 1997.

-

19.

Bar-On R, Parker JDA. The Handbook of Emotional Intelligence. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 2000.

-

20.

Fathi Ashtiyani A. Psychological tests [in Persian]. Tehran, Iran: Besat; 2009.

-

21.

Samouee R. Emotional intelligence test [in Persian]. Tehran, Iran: Ravan Tajhiz; 2004.

-

22.

Bar-On R. Emotional and social intelligence: Insights from the Emotion Quotient Inventory. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 2000. p. 363-88.

-

23.

Sanayee B. Family and marriage scales [in Persian]. Tehran, Iran: Besat; 2008.

-

24.

Soleimaniyan A. Investigation of the influence of irrational thoughts based upon cognitive approach on marital dissatisfaction [in Persian]. Tehran: Tarbiyat Moallem Univ; 1994.

-

25.

Reza Zadeh M. Relationship between attachment styles and communicational skills and marital compatibility in Tehran City Students[ in Persian]. Tehran: Tarbiyat Modarres Univ; 2002.

-

26.

Simpson JA. Influence of attachment styles of romantic relationships. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1990;59:971-80.

-

27.

Fincham FD, Bradbury TN. Marital satisfaction, depression, and attributions: a longitudinal analysis. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1993;64(3):442-52. [PubMed ID: 8468671].

-

28.

Feeney JA, Noller P. Attachment style as a predictor of adult romantic relationships. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1990;58:281-91.

-

29.

Simpson JA, Rholes WS, Nelligan JS. Support seeking and support giving within couples in an anxiety provoking situation: The role of attachment styles. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1992;62:434-46.

-

30.

Pistole MC. Attachment in adult romantic relationships: style of conflict resolution and relationship satisfaction. J Soc Pers Relat. 1989;4:505-10.

-

31.

Senchak M. Leonard KE. Attachment styles and marital adjustment among newlywed couples. J Soc Pers Relat. 1992;9:51-64.

-

32.

Besharat MA. Relation of attachment style with marital conflict. Psychol Rep. 2003;92(3 Pt 2):1135-40. [PubMed ID: 12931932].

-

33.

Feeney JA, Noller P, Callan VJ. Attachment styles, communication, and satisfaction in the early years of marriage. Adv in Pers Relat. 1994;5:269-308.

-

34.

Davila J, Bradbury T, Fincham F. Negative affectivity as a mediator of the association between adult attachment and marital satisfaction. Pers Relat. 1998;5:467-84.

-

35.

Feeney JA. Adult attachment, emotional control, and marital satisfaction. Pers Relat. 1999;6:169-83.

-

36.

Cobb RJ, Davila J, Bradbury TN. Attachment security and marital satisfaction: The role of positive perceptions and social support. Pers Soc Psychol Bull. 2001;27:1131-43.

-

37.

Kachadourian LK, Fincham F, Davila J. Tendency to forgive in dating and married couples : the role of attachment and relationship satisfaction. Pers Relat. 2004;11:373-88.

-

38.

Rivera DL. Adult attachment patterns and their relationship to marital satisfaction. New York: Colombia Univ; 1999.

-

39.

Banse R. Adult attachment and marital satisfaction : evidence for dyadic configuration effects. J Soc Pers Relat. 2004;21:273-82.

-

40.

Najm Qinza J. Attachment styles and emotional intelligence in marital satisfaction among Pakistani men and women. Tennessee: Univ of Tennessee state; 2005.

-

41.

Fizser M. EQ and marital satisfaction. Personal Mastery in Emotional Intelligence. 2002. Available from: http://www.gwimui.imi.ie/eqhtml.

-

42.

Schutte NS, Malouff JM, Bobik C, Coston TD, Greeson C, Jedlicka C, et al. Emotional intelligence and interpersonal relations. J Soc Psychol. 2001;141(4):523-36. [PubMed ID: 11577850].

-

43.

Mehrabian A. Beyond IQ: broad-based measurement of individual success potential or "emotional intelligence". Genet Soc Gen Psychol Monogr. 2000;126(2):133-239. [PubMed ID: 10846622].

-

44.

Vadnais A, Michelle A. The relationship of emotional intelligence and marital satisfaction. J Psychol. 2005;49:579-84.

-

45.

Croyle KL, Waltz J. Emotional awareness and couples' relationship satisfaction. J Marital Fam Ther. 2002;28(4):435-44. [PubMed ID: 12382552].

-

46.

Waldinger RJ, Hauser ST, Schulz MS, Allen JP, Crowell JA. Reading others emotions: The role of intuitive judgments in predicting marital satisfaction, quality, and stability. J Fam Psychol. 2004;18(1):58-71. [PubMed ID: 14992610].

-

47.

Thomas G, Fletcher GO. On-line empathic accuracy in marital interaction. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1997;72:838-50.

-

48.

Geist RL, Gilbert DG. Correlation of expressed and felt emotion during marital conflict. J Pers Individ Dif. 1996;21:49-60.

-

49.

Wenzel A, Graff-Dolezal J, Macho M, Brendle JR. Communication and social skills in socially anxious and nonanxious individuals in the context of romantic relationships. Behav Res Ther. 2005;43(4):505-19. [PubMed ID: 15701360].

-

50.

Tirgari A. relationship between emotional intelligence and marital adjustment and preparation and application of emotional intelligence improvement intervention plan in order to decrease marital maladjustment [dissertation]. [in Persian]. Tehran: Iran: Iran Univ Med Sci; 2004.

-

51.

Tidwell MC, Reis HT, Shaver PR. Attachment, attractiveness, and social interaction: a diary study. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1996;71(4):729-45. [PubMed ID: 8888601].

-

52.

Kirkpatrick LA, Davis KE. Attachment style, gender, and relationship stability: a longitudinal analysis. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1994;66(3):502-12. [PubMed ID: 8169762].

-

53.

Cassidy J. Child-mother attachment and the self in six-year-olds. Child Dev. 1988;59(1):121-34. [PubMed ID: 3342707].

-

54.

Griffin D, Bartholomew K. Models of the self and other; fundamental dimensions underlying measures of attachment. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1994;67:430-45.

-

55.

Lopez FG, Fuendling J, Thomas K, Sagula D. An attachment theoretical perspective on the use of splitting defense. Couns Psychol Q. 1997;10:461-72.

-

56.

Cramer D. Linking conflict management behaviors and relational satisfaction: The intervening role of conflict outcome satisfaction. J Soc Pers Relat. 2002;19:425-32.

-

57.

Schutt NS, Mallouff TM. Characteristic emotional intelligence and emotional well-being. Cogn Emot. 2002;16:769-85.

-

58.

Schutte NS, Malouff JM, Hall LE, Haggerty DJ, Cooper J. T, Golden C. J. Development and validation of a measure of emotional intelligence. J Pers Individ Dif. 1998;25:167-77.

-

59.

Saarni C. Emotional competence. A developmental perspective. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 2000. p. 68-91.

-

60.

Erickson RJ. Reconceptualizing family work: the effect of emotion work on perceptions of marital quality. J Marriage Fam. 1993;55:888-900.

-

61.

Gannon N, Ranzijn R. Does emotional intelligence predict unique variance in life satisfaction beyond IQ and personality? J Pers Individ Dif. 2005;38:1353-64.