Authors:

Faruquzzaman1* and Hossain SM2

1Faruquzzaman, MS Part 3 (Thesis) Course Student, BIRDEM General Hospital, Dhaka, Bangladesh

2Syed Mozammel Hossain, Associate Professor, Department of Surgery, Khulna Medical College Hospital, Bangladesh

Received: 14 February, 2017; Accepted: 19 May, 2017; Published: 22 May, 2017

Faruquzzaman, MS Part 3 (Thesis) Course Student, BIRDEM General Hospital, Dhaka, Bangladesh, E-mail:

Faruquzzaman, Hossain SM (2017) Overall operative outcomes of Laparoscopic Cholecystectomy and our experience in Statistics. Arch Clin Gastroenterol 3(2): 033-036. 10.17352/2455-2283.000035

© 2017 Faruquzzaman, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Laparoscopic cholecystectomy; Complications; Outcome; Gallstones

Background: The laparoscopic surgery technique has rapidly spread because of its several advantages over conventional open surgery. The diminishment of postoperative pain provided positive human impact, and the reduction of length of hospital stay as well as the earlier return to work generated a positive socioeconomic impact. However, despite being minimal invasive this surgical method, postoperative complication cannot be disregarded.

Objective: To evaluate the complications of laparoscopic cholecystectomy in symptomatic and asymptomatic cholelithiasis.

Methodology: 364 & 387 patients of laparoscopic cholecystectomy in BIRDEM General Hospital, Dhaka, Bangladesh and Khulna Medical College Hospital, Bangladesh were included in this prospective study on the basis of convenient purposive sampling from a period of 30.06.14 to 30.09.16 & 01.01.11 to 30.09.16 respectively.

Result: Results of this study suggests that among the patients of BIRDEM, 25.5% cases were male and 74.5% patients were female. Mean±SD of age were 43±1.4 and 42±1.7 respectively. On the other hand, among the KMCH patients, 26.1% were male and 73.9% were female. Mean±SD of age were 46±1.3 and 43±1.9 respectively. Among the total 364 cases in BIRDEM, in case of 277 (76.1% approximately), laparoscopic cholecystectomy was done due to chronic cholecystitis whereas in case of KMCH it was 83.2%. Post cholecystectomy syndrome was found to be the most frequent complications which was recorded 4.7% in BIRDEM and 7.5% in KMCH followed by port site bleeding, 3.8% and 4.4% respectively. The prevalence rates of vascular, hepatic bed haemorrhage were 2.5% & 2.5% respectively in BIRDEM and 2.8% & 3.4% in KMCH. Open conversion rates were 5.2% in BIRDEM and in 7.0% in KMCH. The overall mortality was approximately 1.1% & 2.3% respectively. The prevalence of spilled stone, biliary leakage, bowel injury, port site infection, surgical emphysema were 1.6%, 1.9%, 1.1%, 3.0% & 0.8% respectively in BIRDEM and 1.8%, 2.3%, 1.8%, 4.9% & 0.5% respectively in KMCH.

Conclusion: Laparoscopic cholecystectomy is a safe and effective procedure in almost all patients with cholelithiasis. Proper preoperative work up, awareness of possible complications and adequate training makes this operation a safe procedure with favorable result and lesser complications

Introduction

Laparoscopic cholecystectomy (LC) has replaced open surgery in the treatment of cholelithiasis. It is now considered the first option and has become the “gold standard” in treating benign gallbladder disease [1,2]. The risk of intraoperative injury during laparoscopic cholecystectomy is higher than in open cholecystectomy [3,4]. It has been anticipated that this will diminish with increasing surgeon experience in the use of LC.3 In USA approximately one million patients are newly diagnosed annually with gall disease and approximately 600,000 operations are performed a year more than 75% of them by laparoscopy [5].

Laparoscopic cholecystectomy offers the patients the advantages of minimal invasive surgery. However with the widespread acceptance of LC the spectrum of complications in gallstone surgery has changed. The intraoperative complications of LC like bowel and vascular injury (trocar site), biliary leak and bile duct injuries decrease with the passage of time, because of increased experience of the surgeons, popularity of the procedure and introduction of new instruments [5]. This study represents our experience of laparoscopic cholecystectomy with the aim to evaluate the complications of laparoscopic cholecystectomy in cholelithiasis, both in symptomatic and asymptomatic patients.

Material and Methods

This prospective study was carried out in Surgery Unit 1 of BIRDEM General Hospital, Dhaka, Bangladesh from 30.06.14 to 30.09.16 & in Department of Surgery, Khulna Medical College Hospital (KMCH), Khulna, Bangladesh from 01.01.11 to 30.09.16. All patients undergoing laparoscopic cholecystectomy were included while patients deferred by the anesthetist or undergoing open surgery were excluded from the study.

Preoperative prophylactic antibiotics were given to all patients. Mainly 4-ports entry procedure was adopted. The average operation time was 40 minutes. Single doses of injectable antibiotics was given till the next morning. Patients were mobilized on the same evening while they were discharged home the next morning or the second day with advice for follow up visit 10 days after surgery.

Results

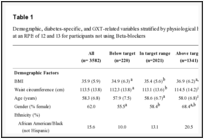

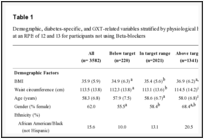

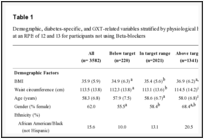

The age and sex distribution of the study population of BIRDEM General Hospital, Dhaka is presented in table 1 which suggest that majority of the patients were female (74.5%). Mean±SD of age was 43±1.4 and 42±1.7 in case of male and female patients respectively (Table 1). On the other hand, the demographic distribution of the study population of KMCH, Khulna is presented in table 2 which suggest that majority of the patients were female (73.9%). Mean±SD of age was 46±1.3 and 43±1.9 in case of male and female patients respectively.

-

Table 2:

Age and sex distribution of study population in BIRDEM.

Majority of the patients of laparoscopic cholecystectomy in BIRDEM were due to chronic cholecystitis (76.1%) followed by 17.0% due to acute cholecystitis. In case of KMCH, these were 83.2% & 9.6% respectively (Table 3).

-

Table 3:

Pathology for which laparoscopic cholecystectomy was done.

Table 4 suggests the overall complications of laparoscopic cholecystectomy in both BIRDEM and KMCH which reflects that the overall open conversion rates are 5.2% and 7.0% respectively and the prevalence rates of mortality are 1.1% in BIRDEM and 2.3 in KMCH.

-

Table 4:

Complications of laparoscopic cholecystectomy.

Discussion

Laparoscopic cholecystectomy (LC) has virtually replaced conventional open cholecystectomy as the gold standard for symptomatic cholelithiasis and chronic cholecystitis [6,7]. In acute cholecystitis the reports are scanty and conflicting7. The application of laparoscopic technique for cholecystectomy is expanding very rapidly and now performed in almost all major cities and tertiary level hospitals in our country. The laparoscopic approach brings numerous advantages at the expense of higher complication rate especially in training facilities [6].

In this study among the patients of BIRDEM, 25.5% cases were male (out of total 364 patients) and 74.5% patients were female. In male group, most of the patients (11.8%) were in 41-50 years of age group followed by 6.3% were in 51-60 years age group, whereas among the female patients it was 40.4% and 19.0% respectively. Mean±SD of age were 43±1.4 and 42±1.7 in case of male and female patients respectively (Table 1). On the other hand, in case of study population at KMCH, 387 patients were included among whom 26.1% were male and 73.9% were female. Most of the male patients (15.8%) were in 41-50 years age group, whereas in case of female it was 32.8%. Mean±SD of age were 46±1.3 and 43±1.9 respectively (Table 2).

In another study majority (59.4%) of the patients were in the age group 21-40 years while 25(7.12%) were less than 20 years of age mainly children with hemolytic anemia referred by pediatrician for elective cholecystectomy. 89.4% were females [8]. However in a study of LC in acute cholecystitis the mean age was 43.7 years with a female to male ratio of 4.5:1.7 In another study of 281 cases of LC there were 140 men and 141 women with a mean age of 56.9 years (range 23-89 years) [8]. Curro et al., recommend elective early LC in children with chronic hemolytic anemia and asymptomatic cholelithiasis in order to prevent the potential complications of cholecystitis and choledocholithiasis which lead to major risks, discomfort and longer hospital stay [9].

Among the total 364 cases in BIRDEM, in case of 277 (76.1% approximately), laparoscopic cholecystectomy was done due to chronic cholecystitis and in 17.0% (62 out of total 364) cases, it was performed due to acute cholecystitis whereas in case of KMCH these were 83.2% and 9.6% respectively. Only in 1.1% cases in BIRDEM and 0.8% cases in KMCH, it was associated with carcinoma of gall bladder (Table 3).

Post cholecystectomy syndrome was found to be the most frequent complications of laparoscopic cholecystectomy which was estimated 4.7% in BIRDEM and 7.5% in KMCH followed by port site bleeding, 3.8% and 4.4% respectively. The prevalence rates of vascular, hepatic bed haemorrhage were 2.5% & 2.5% respectively in BIRDEM and 2.8% & 3.4% in KMCH. Open conversion was done in 19 cases (5.2%) in BIRDEM and in 27 cases (7.0%) in KMCH. It is important to mention that open conversion is not always due to a complication, rather most often it reflects the correct and judicious judgment of the operating surgeon. The overall mortality was approximately 1.1% in BIRDEM and 2.3% in KMCH. The prevalence of spilled stone, biliary leakage, bowel injury, port site infection, surgical emphysema were 1.6%, 1.9%, 1.1%, 3.0% & 0.8% respectively in BIRDEM and 1.8%, 2.3%, 1.8%, 4.9% & 0.5% respectively in KMCH (Table 4).

The reported incidence of injuries from trocars or verses needle is up to 0.2%.5 Bile duct injury is a severe and potentially life threatening complication of LC and several studies report 0.5% to 1.4% incidence bile duct injuries [10-12]. Cystic duct leak is an infrequent but potentially serious complication of LC and can be reduced by using locking clips instead of simple clips [13]. In another series, bile duct injury was minimum and biliary leak occurred in only 14 (3.98%) cases [8]. Vascular injury was encountered in another series. There were 35 (9.97%) cases of trocar site bleeding. Vascular injury in the Callot’s triangle during dissection occurred in 57 (16.23%) cases. 8 only few data are available on the real incidence of bleeding complication from the liver however in a meta-analysis by Shea, 163 patients out of 15,596 suffered vascular injury required conversion with a rate of 8%5. Concomitant vascular injuries during LC increase the overall morbidity [14].

Spillage of gallstones into the peritoneal cavity during LC occurs frequently due to gallbladder perforation and may be associated with complications, and every effort should be made to remove spilled gallstones but conversion is not mandatory [15-17]. Incidence is estimated between 10% and 30% [5]. In a retrospective study from Switzerland, only 1.4% of patients with spillage of gallstones during LC developed serious postoperative complications [5].

Significant reduction in the postoperative infection is one of the main benefits of minimally invasive surgery as the rates of surgical site infection is 2% versus 8% in open surgery [18]. In another study it is reported as 1.4% in laparoscopic surgeries versus 14.8% in open cases [19]. Bowel injuries incidence in LC is 0.07-0.7% and most probably occur during the insertion of the trocars, seldom during operations [20,21].

Conclusions

Laparoscopic cholecystectomy is one of the most frequently performed laparoscopic operations. It has a low rate of mortality and morbidity. It is a safe and effective procedure in almost all patients presenting with cholelithiasis. Most of the complications are due to lack of experience or knowledge of typical error.

A rational selection of patients and proper preoperative work up as well as knowledge of possible complications, initial assessment of anatomy of that intended site prior to operation, proper time of conversion, in combination with adequate training are required. This assessment of correct judgment requires optimal experience of laparoscopy under proper supervision, makes this operation a safe procedure with favorable results.

Acknowledgement

We are grateful & acknowledged to Aysha Afroz Anika, MBBS Student, Gazi Medical College and Khulna, Bangladesh for her valuable time to helping us conducting the research work by data collection & interpretation.

- Ros A, Carlsson P, Rahmqvist M, Bachman K, Nilsson E (2006) Nonrandomized patients in a cholecystectomy trial: characteristics, procedure, and outcomes. BMC Surge 6: 17. Link: https://goo.gl/bTKm5Q

- Ji W, Li LT, Li JS (2006) Role of Laparoscopic subtotal cholecystectomy in the treatment of complicated cholecystitis. Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int 5: 584-589. Link: https://goo.gl/KBimmE

- Hobbs MS, Mai Q, Knuimam MW, Fletcher DR, Ridout SC (2006) Surgeon experience and trends in intraoperative complications in laparoscopic cholecystectomy. BJS 93: 844-853. Link: https://goo.gl/7snYYJ

- Hasl DM, Ruiz OR, Baumert J, Gerace C, Matyas JA, et al. (2001) A prospective study of bile leaks after laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Surg Endosc 15: 1299-1300. Link: https://goo.gl/D2j5Sk

- Shamiyeh A, Wanyand W (2004) Laparoscopic cholecystectomy: early and late complication and their treatment, Langenbecks arch Surg 389: 164-171. Link: https://goo.gl/56m6ie

- Cawich SO, Mitchell DI, Newnham MS, Arthurs MA (2006) comparison of open and laparoscopic cholecystectomy done by a surgeon in training. West Indian Med J 55: 103-109. Link: https://goo.gl/r4iJV2

- Al-Salamah SM (2005) Outcome of laparoscopic cholecystectomy in acute cholecystitis. J Coll Physicians Surg Pak 15: 400- 403. Link: https://goo.gl/TbfvVK

- Chau CH, Siu WT, Tang CN, Ha PY, Kwok SY, et al. (2006) Laparoscopic cholecystectomy for acute cholecystitis: the evolving trend in an institution. Asian J Surg 29: 120-124. Link: https://goo.gl/zZs1nv

- Curro G, Lapichino G, Lorenzini C, Palmeri R, Cucinotta E (2006) Laparoscopic cholecystectomy in children with chronic hemolytic anemia. Is the outcome related to the timing of the procedure? Surg Endosc 20: 252-255. Link: https://goo.gl/PAb7pz

- Lee KW, Poon CM, Leung KF, Lee DW, Ko CW (2005) Two Port needlescopic cholecystectomy: Prospective study of 100 cases. Hong Kong Med J 11: 30-35. Link: https://goo.gl/93cMGD

- Prieto-Díaz-Chávez E, Medina-Chávez JL, González-Ojeda A, Anaya-Prado R, Trujillo-Hernández B, et al. (2006) Direct trocar insertion without pneumoperitoneum and the veress needle in laparoscopic cholecystectomy: a comparative study. Acta Chir Belg 106: 541-544. Link: https://goo.gl/Zy131a

- Frilling A, Li J, Weber F, Fruhaus NR, Engel J, et al. (2004) Major bile duct injuries after laparoscopic cholecystectomy: a tertiary center experience. J Gastrointest Surg 8: 679-685. Link: https://goo.gl/jKZmw9

- Rohatgi A, Widdison AL (2006) An audit of cystic duct closure in laparoscopic cholecystectomies. Surg Endos 20: 875-877. Link: https://goo.gl/n8SaB6

- Tzovaras G, Dernvenis C (2006) Vascular injuries in laparoscopic cholecystectomy: an underestimated problem. Dig Surg 23: 370-374. Link: https://goo.gl/HxJ5wm

- Lin CH, Chu HC, Hsieh HF, Jin JS, Yu JC, et al. (2006) Xanthogranulomatous panniculitis after spillage of gallstones during laparoscopic cholecystectomy mimics intra-abdominal malignancy. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech 16: 248-250. Link: https://goo.gl/AyzV5C

- Loffeld RJ (2006) The consequences of lost gallstones during laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Neth J Med 64: 364-366. Link: https://goo.gl/4xsDYv

- Zehetner J, Shamiyeh A, Wayand W (2007) Lost gallstones in laparoscopic cholecystectomy: all possible complications. Am J Surg 193: 73-78. Link: https://goo.gl/6kY6dp

- Boni L, Benevento A, Rovera F, Dionigi G, Di Giuseppe M, et al. (2006) Infective complications in Laparoscopic surgery. Surg Infect (Larchmet) 2: 5109-5111. Link: https://goo.gl/xtxA93

- Chuang SC, Lee KT, Chang WT, Wand SN, Kuo KK, et al. (2004) Risk factors for wound infection after cholecystectomy. J Formos Med Assoc 103: 607-612. Link: https://goo.gl/zsrmQ4

- Leduc LJ, Metchell A (2006) Intestinal ischemia after laparoscopic cholecystectomy. JSLS 10: 236-238. Link: https://goo.gl/vFul7B

- Baldassarre GE, Valenti GE, Torino GE, Prosperi Porta GE, Valente GE et al. (2006) Small bowel evisceration after laparoscopic cholecystectomy: report of an unusual case. Minerva Chir 6: 167-169. Link: https://goo.gl/U3itbl

Table 1:

Age and sex distribution of study population in BIRDEM.

Age in years

Male

%

Mean±SD

Female

%

Mean±SD

20-30

02

0.5

43±1.4

06

1.6

42±1.7

31-40

19

5.2

33

9.1

41-50

43

11.8

147

40.4

51-60

23

6.3

69

19.0

>60

06

1.6

16

4.4

Total

93

25.5

271

74.5