Abstract

Due to gravitational self-compression, the pressure in planetary interiors can reach millions of times the atmospheric pressure. Such high pressure has a significant influence on their rheology. In the present paper, we focus on how pressure in the range of the Earth’s lower mantle may influence the structure of a MgO {310}/[001] tilt boundary. The defected structure of the grain boundary (GB) will be described through its dislocation, disclination, and generalized-disclination (g-disclination) density fields. At first, the strain and rotation fields in the boundary area at different pressures are derived from the discrete atomic positions simulated by first-principles calculations. For each pressure, the discontinuities of displacement, rotation, and strain in the boundary area are continuously rendered by dislocation, disclination, and g-disclination density fields, respectively. These density fields measured at different pressures are compared to provide understanding on how pressure does influence the GB structures in Earth materials.

Similar content being viewed by others

I. INTRODUCTION

In the Earth’s mantle, with increasing depth, pressure increases rapidly, reaching values as high as 136 GPa at the base of the mantle.1 These ultrahigh pressures have profound implications on the rheology of the Earth’s constituents that can be quite different from that observed at ordinary pressure. Therefore, it is of primary importance to investigate the mechanical behavior of the high-pressure phases of the deep Earth to understand the structure and dynamics of the Earth’s interior.

Below 670 km, the phase assemblages present in the Earth’s transition zone decompose into a mixture of silicates with the perovskite structure and magnesium oxides (containing some iron). The high-pressure behavior of periclase (MgO) is thus of major importance in the rheology of the Earth’s interior. MgO is an ionic solid, which is chemically and physically stable at high temperatures and pressures. It can keep its NaCl-type structure up to 227 GPa confining pressure.2 This unique structural stability makes MgO an ideal benchmark for investigating the behavior of solids at extreme pressure conditions. The structure and elasticity of MgO at high pressure have been widely studied by using first-principles calculations. Indeed, pressure-induced variation of the elastic moduli arises from changes in the structure and nature of atomic bondings under pressure and from phase transformations.1 For instance, the individual elastic moduli of MgO throughout Earth’s mantle pressure regime have been obtained with density functional theory. It was found that the pressure-induced elastic anisotropy is preserved down to the Earth’s lowest mantle.3 The pressure-induced phase transformation of MgO was compared with that of other ionic and solids.4 The elastic moduli, the intrinsic anharmonic parameters, and the B1–B2 transition pressure of MgO were determined from ab initio calculations. Simulation results show that MgO keeps its NaCl-type B1 structure at all pressures existing within the Earth, and that the critical pressure at which MgO transforms into the CsCl-type B2 structure is 509 GPa.5,6

In the Earth’s mantle, MgO is present in the form of polycrystalline aggregates, which exhibit various grain sizes and grain boundary (GB) misorientation angles. GBs in MgO significantly influence polycrystal elasticity and plasticity, and have attracted intensive research interest among high-pressure experimentalists. Merkel et al. used diamond anvil cell coupled with in situ synchrotron x-ray diffraction measurements to investigate the evolution of yield strength and deformation mechanisms of MgO polycrystals at pressures up to 47 GPa.7 Marquardt et al. carried out Brillouin scattering experiments on MgO nanocrystals to characterize their elastic properties and GBs at high pressures.8 It was found that at high pressures, the small grain sizes have profound effects on the elastic properties. Van Orman et al. performed high-pressure diffusion experiments in MgO to investigate the rheological and chemical transport properties within the lower mantle.9 Recent deformation experiments performed under lower mantle conditions by Girard et al.10 on bridgmanite and (Mg, Fe)O aggregates have shown that the rheology contrast between the two phases leads to phase separation and shear localization within oxide-rich domains. Hence, the mechanical properties of GBs in MgO at high-pressure are expected to contribute significantly to the rheology of the deep mantle.

First-principles methods and molecular dynamics simulations are efficient modeling tools that allow studying the physical properties of GBs in MgO at the atomic scale11–14 under high pressures. The atomic and electronic structures of three {n10}/[001] MgO tilt GBs (n = 2, 3, and 4) were investigated as a function of pressure by using the density functional theory.14 Using a similar method, the ability of MgO GBs to accommodate point defects and enhance diffusion rates was explored. Results show that defects and impurities (Ca, Al, and proton) segregate preferentially within the boundary area and that the segregation susceptibility considerably increases with pressure.15

Continuous modeling of the structure of GBs using smooth first order/second order distortion fields and crystal defect density fields at interatomic scale is attractive because it provides the basis for a mechanical description of the lattice defects. Attractiveness of continuous modeling at this scale derives further from its ability to serve as a basis for coarse-grained representations of polycrystalline media. Within a recent elasto-plastic framework proposed by Fressengeas et al.16 and Acharya–Fressengeas,17 it was shown that dislocation, disclination and generalized-disclination (g-disclination) density fields were appropriate mathematical objects for a consistent continuous description of the atomic defected structures, energetics, and dynamics of GBs.18–20 For instance, disclinations were found to decorate GBs in minerals and were proposed as good candidates at providing plastic accommodation mechanisms in dislocation slip-deprived rocks in the upper mantle.19 Here we focus on how pressure influences the dislocation, disclination, and g-disclination structures of a MgO {310}/[001] tilt GB. At first, the discrete atomic positions simulated by first-principles calculations are used to derive the strain and rotation fields in the boundary area at different pressures. Then, the dislocation, disclination and g-disclination density fields are calculated to study the influence of pressure on the defected structure of GBs, in terms of discontinuities of elastic displacement, rotation, and strain fields.

II. MODELING METHODS

A. MgO boundaries from first principles calculations

The MgO GB studied here is a {310}/[001] (misorientation θ = 36.8°) tilt boundary, which was constructed in a previous work.14 The initial configuration of the GB before self-relaxation was created by the following two steps. At first, two blocks of MgO single crystals are cut along \(\left( {310} \right)\) and \(\left( {3\bar 10} \right)\) surfaces, respectively, and rotated about the [001] axis. Then, the two MgO cut blocks are joined together and the initial unrelaxed GB is formed. After the initial configuration of the GB was generated, the structure was relaxed using the Vienna ab-initio simulation package with local density approximation and projector-augmented-wave method.21 A plane wave cutoff energy of 450 eV and Gamma-point Brillouin zone sampling were used. Both cell parameters and atomic positions were optimized for the boundary supercell containing 560 atoms according to pressure in the range 0–150 GPa. Doubling the supercell did not affect the calculated boundary structure significantly.

The relaxed configurations of asymmetric MgO {310}/[001] GBs at 0, 50, 100, and 150 GPa pressures are shown in Figs. 1(a), 1(b), 1(c), and 1(d), respectively. Atoms are represented by black dots, and the atomic structural units composing the boundaries are delineated by blue lines. As can be seen in Fig. 1(a), the GB structure at 0 GPa is made of hexagon-like atomic structural units, which are similar to those at 50 GPa [see Fig. 1(b)]. However, as far as the pressure reaches 100 or 150 GPa, the hexagon-like structural units evolve toward more triangular and thin shapes [Fig. 1(c)].

B. From atomic to continuous description of GB structures

The atomic structures of the relaxed and unrelaxed configurations obtained from first-principles calculations are now used to derive the continuous dislocation/disclination/g-disclination fields characterizing the lattice incompatibility in the defected area of the GB. The following steps are performed:

-

(i)

Local values of the transformation gradient tensor at each atomic position are computed by using the atomic positions in the reference and deformed configurations. As it is less energetic, the reference configuration is taken as the relaxed GB structure and the current configuration is the initial unrelaxed GB structure.

-

(ii)

Elastic strain, rotation, curvature tensor fields and then dislocation, disclination, and g-disclination density field values are calculated at each atomic position by following the methods recently introduced20 (see also the Appendix).

-

(iii)

Linear interpolation is used to generate spatial field distributions in between atoms from local values at atoms. In the linear interpolation of fields, the mesh size is 0.5 angstrom.

This method has been applied to a 18.9° and a 60.8° symmetrical tilt boundary in copper and forsterite, respectively,20,22 and its accuracy/reliability was checked by comparison with recent similar techniques.23,24

III. RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

A. Elastic fields

Strain is a measure of the deformation of the body with respect to a reference configuration. The ε22 strain fields of the MgO boundary at 0, 50, 100, and 150 GPa pressures are displayed in Figs. 1(a), 1(b), 1(c), and 1(d), respectively. The strains ε11 and ε12 are shown in the Supplementary Materials. The ε22 component (strain normal to the GB plane) is larger than the others and is chosen to characterize the influence of pressure. As plotted in Fig. 1(a), the strain field ε22 at 0 GPa is located along the boundary with alternate signs across the GB interface. The extreme values of the contractions and extensions form dipoles, and they are located in areas in between the structural units and are extremely close to the interface. Figure 1(b) shows the strain ε22 of the boundary at 50 GPa. The shape of dipoles in Fig. 1(b) is quite close to that at 0 GPa, but the magnitude of strains is about 0.15, which is only 60% of that at 0 GPa. The ε22 strain fields at 100 and 150 GPa are displayed in Figs. 1(c) and 1(d), respectively. The extreme values of the contractions and extensions of ε22 at 100 or 150 GPa are also located along the interface with alternate signs across the boundary. However, as compared with the ε22 strain fields at 0 and 50 GPa, strain quadrupoles, rather than dipoles, are seen.

The elastic tilt rotation field ω of the boundaries at 0, 50, 100, and 150 GPa are plotted in Figs. 2(a), 2(b), 2(c), and 2(d), respectively (rotation around the axis perpendicular to the figures). For the four pressures studied, tilt rotation dipoles are observed and are located within a 6 Å thick layer along the interface. It is observed that the shapes of rotation fields at 0 and 50 GPa are very similar. Just like the strain field shown in Fig. 1, ω has relatively smaller values at 50 GPa than at 0 GPa. However, at 100 and 150 GPa, the dipolar structure of the rotation fields significantly differs: At 100 or 150 GPa, the dipole arms are arranged along a straight line subparallel to the boundary plane. At 0 and 50 GPa, they are inclined with respect to the GB plane, and subsequent dipoles tend to form a zigzag pattern.

B. Dislocation and disclination density fields

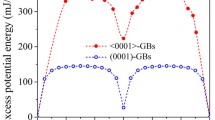

The discontinuities of the displacement and rotation fields in the GB interface area can be described by using Volterra’s model defects, i.e., dislocations and disclinations, respectively. By using the elasto-plastic model of dislocation and disclination fields,16 the disclination density θ33 and dislocation density (α13, α23) fields are used to characterize the discontinuity of tilt elastic rotation and of the in-plane displacements (displacements in the plane of the figures). The calculated defect densities are displayed in Fig. 3 for the four pressures studied. The defect topology reflected by the wedge disclination density θ33 is an elastic rotation discontinuity around the axis perpendicular to the figure, supported by a defect line aligned with that same axis. The edge dislocation densities (α13, α23), respectively, render horizontal and vertical Burgers vectors, supported by the same defect line parallel to the GB tilt axis (axis perpendicular to the figure plane). In this figure, the disclination density is color-coded and the dislocation densities are represented by the associated in-plane components of the Burgers vector field per unit surface (arrows). It can be seen that the disclination and dislocation distributions are confined to a thin 6 Å layer along the interface.

The disclination dipole structures (shape and strength) are very similar at 0 GPa [Fig. 3(a)] and at 50 GPa [Fig. 3(b)]. In both cases, the disclination dipoles are subsequently arranged in a zigzag manner, just like the rotation fields. It is indeed seen that the disclination dipoles accommodate the strong rotation variations (jumps) along the GB interface. However, the disclination density field at 100 GPa is radically different from that at 50 GPa. In Fig. 3(c), the disclination dipoles at 100 GPa are arranged along a straight line parallel to the GB plane, the positive (resp. negative) pole being at the left (resp. right) end of the structural units. The maximum local magnitude of disclination densities at 100 GPa is 0.18 rad/Å2, almost two times larger than that at 50 GPa. Similarly, the local dislocation density values (α13, α23) are larger at 100 GPa than at 50 GPa. The disclination dipoles at 150 GPa are plotted in Fig. 3(d). The shape and strength of disclination dipoles slightly differs from 100 GPa to 150 GPa, except that the position of disclination dipoles at 150 GPa is more symmetrical with respect to the boundary plane, while dipoles at 100 GPa are a little offset downward.

The Burgers vector components associated with the (α13, α23) dislocation density distribution are now computed, together with the Frank vector component associated with the wedge disclination density field θ33. The Frank vector Ω is defined as the angular closure defect, which can be obtained by integrating the elastic curvature tensor along a closed circuit C, and equivalently by:

where S is the surface of unit normal n delimited by C. In the present MgO case, the Frank vector resulting from the distribution of the disclination density θ33 over a surface S in the plane (e1, e2) is

As the pressure increases from 0 to 50 GPa, the \(\left\langle {001} \right\rangle \) Frank vector component decreases from 1.02 to 0.63 radian (58° to 36°). However, the \(\left\langle {001} \right\rangle \) Frank vector component increases up to 0.96 radian (55°) at 100 GPa, and reaches to 1.10 radian (63°) at 150 GPa. This variation trend is consistent with the evolution of disclination spatial distributions for the four pressures (Fig. 3).

The Burgers vector is now defined as

In the above, r is the position vector and the disclination densities have a nonlocal impact on the Burgers vector. In the plane (e1, e2), Eq. (3) reduces to

We find that the magnitude of the in-plane Burgers vector (in the plane of the figures) changes from b = 0.83 Å at 0 GPa to b = 0.39 Å at 50 GPa, then it increases to b = 1.27 Å at 100 GPa, and finally equals b = 1.15 Å at 150 GPa. Again, the relationship between the magnitude of the Burgers vector and pressure is consistent with the variation of the dislocation density fields with pressure.

C. G-disclination density fields

As evidenced above, the boundaries exhibit discontinuities of the elastic displacement and rotation fields in the GB interface area, which can be described by a distribution of dislocation and disclination densities. However, it is also observed that the GB exhibits discontinuities of the elastic strain tensor. As recently discussed,17 the discontinuity of the elastic distortion (rotation plus strain) can be smoothly described by g-disclination densities. The g-disclination densities complement standard disclinations by rendering the discontinuity of strain in addition to the discontinuity of rotation.

The strain ε22 (see Fig. 1) shows a more discontinuous spatial distribution than other strain components, (see Supplementary Materials). The g-disclination density field ξ223, which reflects the discontinuity of strain ε22 supported by a defect line parallel to the GB tilt axis, is plotted in Fig. 4 for the four pressures investigated. Similarly to the disclination field, all the g-disclination density fields show a positive (resp. negative) pole at the left (resp. right) end of the structural units. However, the g-disclination densities ξ223 at 100 or 150 GPa are much higher in magnitude than in the two other cases, implying discontinuities of strain ε22.

IV. CONCLUSIONS

By using an atomistic-to-continuum crossover method, we provide a continuous description of the defect density fields within a MgO {310}/[001] tilt GB at different pressures. The elastic fields such as strain and rotation fields at each pressure are calculated in the boundary area from discrete atomic positions. Then dislocation, disclination and g-disclination density fields are calculated and used to describe discontinuities in the fields of displacement, rotation, and strain in the GB area at each pressure. Results show that as the pressure increases from 0 to 50 GPa, the intensities of all elastic fields (displacement, rotation, and strain) and the intensity of all defect density fields decrease while then, they increase when the pressure reaches 100 GPa. We show here that pressure has a strong effect on the defected structure of GBs, and the evolution does not follow a simple tendency of compacting structures with increasing pressure. Indeed, the defect structure of the boundary is significantly modified, which has potential implications on its elastic energy level and mobility under stress, with consequences in particular on the plasticity of polycrystalline aggregates. Further work is in progress to quantify these effects.

References

B.B. Karki, L. Stixrude, and R.M. Wentzcovitch: High-pressure elastic properties of major of Earth’s from first principles. Rev. Geophys. 39 (4), 507–534 (2001).

T.S. Duffy, R.J. Hemley, and H.K. Mao: Equation of state and shear strength at multimegabar pressures: Magnesium oxide to 227 GPa. Phys. Rev. Lett. 74, 1371–1374 (1995).

B.B. Karki, R.M. Wentzcovitch, S. de Gironcoli, and S. Baroni: First-principles determination of elastic anisotropy and wave velocities of MgO at lower mantle conditions. Science 286 (5445), 1705–1707 (1999).

B.B. Karki, G.J. Ackland, and J. Crain: Elastic instabilities in crystals from ab initio stress-strain relations. J. Phys.: Condens. Matter 9 (41), 8579–8589 (1997).

A.R. Oganov and P.I. Dorogokupets: All-electron and pseudopotential study of MgO: Equation of state, anharmonicity, and stability. Phys. Rev. B: Condens. Matter Mater. Phys. 67 (22), 224110 (2003).

B.B. Karki, L. Stixrude, S.J. Clark, M.C. Warren, G.J. Ackland, and J. Crain: Structure and elasticity of MgO at high pressure. Am. Mineral. 82 (1–2), 51–60 (1997).

S. Merkel, H.R. Wenk, J. Shu, G. Shen, P. Gillet, H.K. Mao, and R.J. Hemley: Deformation of polycrystalline MgO at pressures of the lower mantle. J. Geophys. Res. 107 (B11), 2271 (2002).

H. Marquardt, A. Gleason, K. Marquardt, S. Speziale, L. Miyagi, G. Neusser, H.R. Wenk, and R. Jeanloz: Elastic properties of MgO nanocrystals and grain boundaries at high pressures by Brillouin scattering. Phys. Rev. B: Condens. Matter Mater. Phys. 84 (6), 064131 (2011).

J.A. Van Orman, Y. Fei, E.H. Hauri, and J. Wang: Diffusion in MgO at high pressures: Constraints on deformation mechanisms and chemical transport at the core-mantle boundary. Geophys. Res. Lett. 30 (2), 26–29 (2003).

J. Girard, G. Amulele, R. Farla, A. Mohiuddin, and S.I. Karato: Shear deformation of bridgmanite and magnesiowustite aggregates at lower mantle conditions. Science 351 (6269), 144–147 (2016).

D.J. Harris, G.W. Watson, and S.C. Parker: Atomistic simulation of the effect of temperature and pressure on the [001] symmetric tilt grain boundaries of MgO. Philos. Mag. A 74 (2), 407–418 (1996).

Y. Yan, M.F. Chisholm, G. Duscher, A. Maiti, S.J. Pennycook, and S.T. Pantelides: Impurity-induced structural transformation of a MgO grain boundary. Phys. Rev. Lett. 81 (17) 3675–3678 (1998).

M. Saito, Z. Wang, and Y. Ikuhara: Selective impurity segregation at a near-∑5 grain boundary in MgO. J. Mater. Sci. 49 (11), 3956–3961 (2014).

A.K. Verma and B.B. Karki: First-principles simulations of MgO tilt grain boundary: Structure and vacancy formation at high pressure. Am. Mineral. 95 (7), 1035–1041 (2010).

B.B. Karki, D.B. Ghosh, and A.K. Verma: First-principles prediction of pressure-enhanced defect segregation and migration at MgO grain boundaries. Am. Mineral. 100 (5–6), 1053–1058 (2015).

C. Fressengeas, V. Taupin, and L. Capolungo: An elasto-plastic theory of dislocation and disclination fields. Int. J. Solids Struct. 48 (25), 3499–3509 (2011).

A. Acharya and C. Fressengeas: Coupled phase transformations and plasticity as a field theory of deformation incompatibility. Int. J. Fract. 174 (1), 87–94 (2011).

C. Fressengeas, V. Taupin, and L. Capolungo: Continuous modeling of the structure of symmetric tilt boundaries. Int. J. Solids Struct. 51 (6), 1434–1441 (2014).

P. Cordier, S. Demouchy, B. Beausir, V. Taupin, F. Barou, and C. Fressengeas: Disclinations provide the missing mechanism for deforming olivine-rich rocks in the mantle. Nature 507 (7490), 51–56 (2014).

X.-Y. Sun, V. Taupin, C. Fressengeas, and P. Cordier: Continuous description of the atomic structure of grain boundaries using dislocation and generalized-disclination density fields. Int. J. Plast. 77, 75–89 (2016).

X.-Y. Sun, P. Cordier, V. Taupin, C. Fressengeas, and S. Jahn: Continuous description of a grain boundary in forsterite from atomic scale simulations: The role of disclinations. Philos. Mag. 96, 1757–1772 (2016).

G. Kresse and J. Furthmüller: Efficiency of ab-initio total energy calculations for metals and semiconductors using a plane-wave basis set. Comput. Mater. Sci. 6 (1), 15–50 (1996).

P.M. Gullett, M.F. Horstemeyer, M.I. Baskes, and H. Fang: A deformation gradient tensor and strain tensors for atomistic simulations. Modell. Simul. Mater. Sci. Eng. 16 (1), 015001 (2008).

J.A. Zimmerman, D.J. Bammann, and H.J. Gao: Deformation gradients for continuum mechanical analysis of atomistic simulations. Int. J. Solids Struct. 46 (2), 238–253 (2009).

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

This work was supported by funding from the European Research Council under the ERC Grant No. 290424—RheoMan.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

This paper has been selected as an Invited Feature Paper.

Supplementary Material

APPENDIX

APPENDIX

In this appendix, the kinematics of the elasto-plastic incompatibility associated with crystal defect fields is briefly recalled. Since compatible plastic processes are not envisioned in the present paper, compatibility is about elastic deformation measures only.

A.1. Displacement gradient

A fixed Cartesian coordinate system is assumed to describe the changes in the shape, size, and orientation of a simply connected continuous crystalline body containing defects. For each point, the Lagrange and Euler coordinates X and x label the positions of a material element in the reference and deformed state, respectively. x is a function of X, and the transformation gradient of x(X) is defined as the second order tensor

The total displacement field u = x − X describes the changes in position of matter. This field is assumed to be single valued and continuous, possibly between atoms and below interatomic distances. Thus, matter is assumed to be able to transmit stresses and couple stresses at this scale. The displacement gradient, also referred to as the distortion tensor, is

where I is the second order identity tensor and \({\delta _{ij}}\) is Kronecker delta,

A.2. Strain, rotation, and curvature tensors

Strain is a measure of the deformation of the body with respect to a reference configuration. The strain tensor \(\varepsilon \) is the symmetric part of the distortion grad u,

The rotation tensor ω is the skew-symmetric part of the distortion grad u,

and the associated rotation vector \(\overrightarrow {\bf{\omega }} \) reads

where \({e_{ijk}}\) is the alternating Levi-Civita tensor,

From the rotation vector \({\vec \omega }\), the curvature tensor κ can be defined as

A.3. Disclination, dislocation, and g-disclination density tensors

In the absence of plasticity, the curvature tensor \({\bf{\kappa }}\) can be identified with its compatible elastic component \({\bf{\kappa }}_{\rm{e}}^{//}\). However, the elastic curvature tensor also comprises an incompatible part \({\bf{\kappa }}_{\rm{e}}^ \bot \), which counter-balances the incompatible plastic curvature \({\bf{\kappa }}_{\rm{p}}^ \bot \) arising from the presence of crystal defects because continuity of the body is maintained. As a result, the elastic curvature tensor \({{\bf{\kappa }}_{\rm{e}}} = {\bf{\kappa }}_{\rm{e}}^ \bot + {\bf{\kappa }}_{\rm{e}}^{//}\) may not be curl-free, even if the total curvature tensor κ is compatible. This rotational incompatibility is conveniently described by the continuous disclination density tensor

deriving from the incompatible part \({\bf{\kappa }}_{\rm{e}}^ \bot \) of the elastic curvature. The same line of reasoning applies to the elastic strain tensor, which results in defining Nye’s dislocation density tensor α from the incompatible elastic strain field and curvature field through

In the finite strain assumption, the dislocation density tensor α is obtained from the elastic transformation tensor Fe through the relation

To describe the strain discontinuity, the third-order tensor ξ is defined as

where \(G_{ijm}^{{\rm{e}},{\rm{sym}}} = {1 \over 2}{(u_{i,j}^{\rm{e}} + u_{j,i}^{\rm{e}})_{,m}} = \varepsilon _{ij,m}^{\rm{e}}\) is a component of the symmetric part of the elastic second distortion tensor.

Rights and permissions

This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Sun, XY., Taupin, V., Cordier, P. et al. Influence of pressure on dislocation, disclination, and generalized-disclination structures of a {310}/[001] tilt grain boundary in MgO. Journal of Materials Research 31, 3108–3114 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1557/jmr.2016.346

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1557/jmr.2016.346