Introduction

During the more than a decade-long civil war, Syria has seen systematic destruction of its cultural heritage, hereunder Palmyra's art and architecture, and the diaspora of Syrian nationals displaced from their home country. As an additional consequence, researchers were also unable to work in the country. These circumstances have made apparent the need to document, preserve and disseminate knowledge about the country's cultural heritage. The project Archive Archaeology: Preserving and Sharing Palmyra's Cultural Heritage through Harald Ingholt's Digital Archives, established by Rubina Raja in 2020 (https://projects.au.dk/archivearcheology/), is one example of such an initiative. It will make the archive of Palmyrene funerary sculpture, compiled by Danish archaeologist Harald Ingholt (hereafter the Ingholt Archive), available both in print and as an eBook—in an extensive, annotated publication—and freely online as open data in the form of the raw data: high-resolution scans of the original archive sheets, under a CC BY4.0 licence (Raja Reference Raja2021). The print and electronic publications contain transcriptions of each archive sheet and accompanying commentary (Bobou et al. in press). Also freely available online as open data, the archive appears in pdf format (Bobou et al. Reference Bobou, Miranda and Raja2021). Such publications will mitigate some issues in accessing archives that were particularly acute during the COVID-19 pandemic, when scholars were limited in their access to physical resources. They will also strengthen the archive's reuse potential by the academic community and public. Enhancing the accessibility of the Ingholt Archive aims to set a benchmark for best practice in archaeology and lead by example in future research and cultural heritage preservation initiatives. The archive has already begun to yield such results, as it provided the foundation for the digital reconstruction of the Tomb of Ḥairan (Bobou et al. Reference Bobou, Kristensen, McAvoy and Raja2020). Digital models and other forthcoming research, such as work on looted and faked sculptures, will aid restitution efforts in Syria. As a further example, we here introduce the Exedra of Julia Aurelius Maqqaî to illustrate the potential of archival material in archaeology.

The Exedra of Julius Aurelius Maqqaî

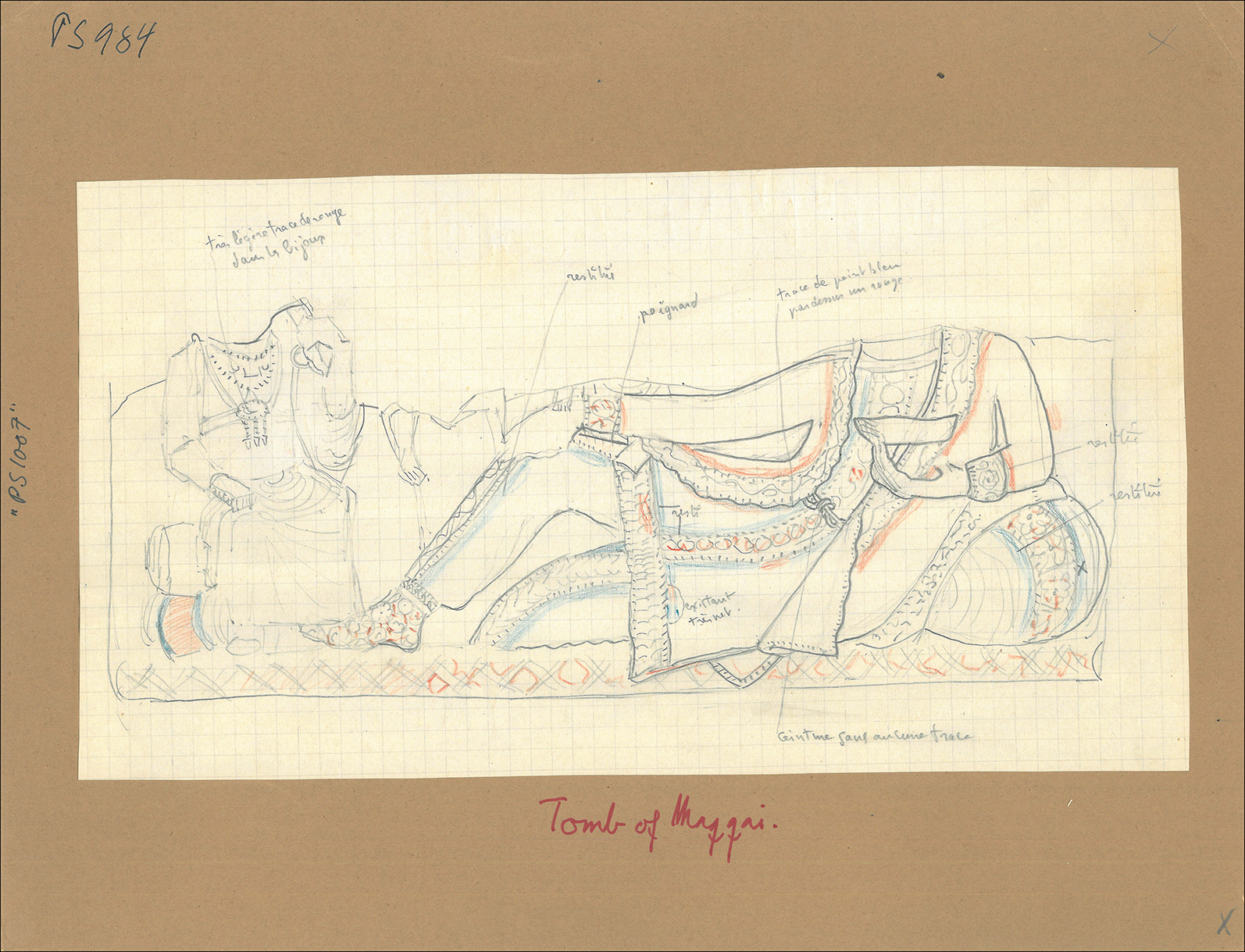

Twelve sheets from the archive labelled PS 984 and 985 (PS: an abbreviation for Palmyrene Sculpture used by Ingholt) show a complete sarcophagus from the Exedra of Julius Aurelius Maqqaî in the Hypogeum of ʿAtenatan (Figure 1). The tomb is located in Palmyra's south-west necropolis and although excavated by Ingholt in 1924, it was never fully published (Ingholt Reference Ingholt1935: 58; Raja et al. Reference Raja, Steding and Yon2021: Diary 1: 30. 73. 86 ff. & 123 f, Diary 2: 87, Diary 3: 45. 69. 72 & Diary 5: 76 ff.). Four of the archive sheets labelled PS 984 and 985 are drawings of the sarcophagus, with blue, red and yellow colourings indicating the object's original tones. Two sheets, both labelled PS 984, show a sarcophagus lid with a banqueting scene (Figure 2) and a sarcophagus box with a trade scene (Figure 3). A third sheet, labelled PS 984A, shows a sarcophagus lid with a banqueting scene (Figure 4), while a fourth sheet labelled PS 985 shows a sarcophagus box with a trade scene (Figure 5). Yet another sheet, labelled PS 984, contains two black and white photographs of a sarcophagus; the lower image is manually coloured with red and blue pigments (Figure 6). In all these cases, given Ingholt's annotations on the drawings, it seems that traces of colour were present on the sarcophagus, both the lid and box.

Figure 1. Archive sheet PS 984-985, showing a sarcophagus in the Exedra of Julius Aurelius Maqqaî (© Palmyra Portrait Project, Ingholt Archive at Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek and Rubina Raja).

Figure 2. Archive sheet PS 984. Drawing of a sarcophagus lid with banqueting scene (© Palmyra Portrait Project, Ingholt Archive at Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek and Rubina Raja).

Figure 3. Archive sheet PS 984. Drawing of a sarcophagus box with trade scene (© Palmyra Portrait Project, Ingholt Archive at Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek and Rubina Raja).

Figure 4. Archive sheet PS 984A. Drawing of a sarcophagus lid with banqueting scene (© Palmyra Portrait Project, Ingholt Archive at Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek and Rubina Raja).

Figure 5. Archive sheet PS 985. Drawing of a sarcophagus box with trade scene (© Palmyra Portrait Project, Ingholt Archive at Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek and Rubina Raja).

Figure 6. Archive sheet PS 984, showing two photographs of a sarcophagus in the Exedra of Julius Aurelius Maqqaî (© Palmyra Portrait Project, Ingholt Archive at Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek and Rubina Raja).

This visual and written information is foundational for digital reconstruction or recontextualisation of objects, to name but two examples. In the case of PS 984 and 985, Ingholt's thorough documentation is particularly critical. The depicted sarcophagus’ last known location was in situ in the exedra, and Ingholt's photographs in the archive show the sarcophagus there (Figures 1 & 6). Despite its known excavation history and its documentation in the archive, the Syrian civil war and the destruction of art and architecture mean that this, and many other objects, cannot now be accurately accounted for. Should this sarcophagus have been damaged or looted, the images and annotations of the Ingholt Archive will prove a valuable resource to those interested in the preservation of Syrian cultural heritage—scholars and the public alike.

Conclusion

Although lost heritage cannot be replaced, making archives, such as the Ingholt Archive, accessible is a step forward for archaeology and cultural heritage preservation efforts. Archives allow for rigorous historiographic study and the accumulation of deep knowledge of archaeological sites, their art and architecture. The publication of the Ingholt Archive aims to set a new standard in archaeology for making information accessible and reusable and to raise the profile of archival work within the discipline of archaeology.

The need for the sharing and utilising of archival material—particularly in conflict zones—is an issue not only pertinent to Syria, as the escalating conflict in Afghanistan has shown. As part of the commitment to the preservation of heritage, the Archive Archaeology project has compiled a list of cultural heritage resources (https://projects.au.dk/archivearcheology/cultural-heritage-resources/) and has drawn upon the archive to produce several works on the preservation of Palmyra (Raja Reference Raja, Raja and Sørensen2015, Reference Raja, Almqvist and Belfrage2016a, Reference Raja, Chahin and Lindblom2016b, Reference Raja2020). Archives must be made accessible in order to be utilised by scholars and members of the public with an interest in the ancient world and heritage preservation; they are currently under-utilised, despite the wealth of information they contain.

Acknowledgements

Since Rubina Raja founded the Palmyra Portrait Project in 2012 (https://projects.au.dk/palmyraportrait/), several individuals have contributed to the study of Palmyrene sculpture. The authors wish to thank everyone who has participated in the project.

Funding statement

The initial research on the Ingholt Archive was performed by the Palmyra Portrait Project, with a Carlsberg Foundation grant (CF15-0493) held by Rubina Raja. The continued research on the digital archive performed by the project Archive Archaeology: Preserving and Sharing Palmyra's Cultural Heritage through Harald Ingholt's Digital Archives, was funded by the ALIPH foundation with a grant (2019-1267) also held by Rubina Raja. The authors thank the funders for their support.