Measuring sexual behaviours and attitudes in hard-to-reach groups. A comparison of a non-probability web survey with a national probability sample survey

Geary R.S., Couper M.P., Erens B., Copas A.J., Burkill S., Sonnenberg P., Conrad F. & Mercer C.H. (2019). Measuring sexual behaviours and attitudes in hard-to-reach groups. A comparison of a non-probability web survey with a national probability sample survey. Survey Methods: Insights from the Field. Retrieved from https://surveyinsights.org/?p=10433

© the authors 2019. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (CC BY 4.0)

Abstract

Introduction: Hard-to-reach and minority groups are often at higher risk for adverse sexual health outcomes. While such groups are therefore of interest to sexual health researchers, it can be difficult to locate and recruit sufficient sample sizes using probability sampling methods. This study aims to establish whether web-panel surveys can provide a viable less resource intensive means of boosting sample sizes of two hard-to-reach groups (people of Black African ethnicity, and gay men) for a sexual health survey, and the extent of any bias. Methods: Results from a national probability sample survey (Natsal-3, administered using a computer-assisted personal interview (CAPI) and self-interview (CASI) with 15,162 participants), which included 211 black African participants and 83 gay men, were compared with results from a web-panel survey (using identical questions) of 529 black Africans and 592 gay men. Web-panel survey results for socio-demographics were compared with external benchmarks, and for sexual behaviours and attitudes reported in Natsal-3. Odds ratios (ORs) were used to examine differences between variables and the average absolute OR, along with the number of estimates for which the web-panel survey differed significantly from the benchmarks, were used to summarise survey performance. Results: At least 18% of estimates differed significantly between surveys for gay and black African men, and 28% for black African women. For black African women average absolute ORs were: 1.6 for attitudinal questions asked in CAPI, 1.5 for attitudinal CASI questions, 3.2 for behaviour questions asked in CAPI and for 1.7 for behaviour CASI. For black African men average absolute ORs were: 1.5 for attitudinal questions asked in CAPI, 1.8 for attitudinal CASI questions, 2.5 for behavioural questions asked in CAPI and 1.6 for behavioural questions asked in CASI=1.6. For gay men, average absolute ORs were: 2.2 for attitudinal questions asked in CAPI, 2.8 for attitudinal CASI questions, 1.8 for behavioural questions asked in CAPI to 1.6 for behavioural questions asked in CASI. Discussion: Web-panel surveys may be able to sample hard-to-reach groups but may not be able to replace probability-sample surveys where accurate population-level estimates of sensitive sexual behaviours are required. Differences between web and CASI responses, where mode effects may be similar, suggest web-panel survey selection bias.

Keywords

hard to reach populations, non-probability samples, probability samples, sexual health, Web surveys

Acknowledgement

Funding statement Natsal-3 is a collaboration between University College London, the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, NatCen Social Research, the Health Protection Agency, and the University of Manchester. This supplementary study comparing the web-panel survey to Natsal-3 also included collaborators from the University of Michigan (Ann Arbor, MI, USA). The study was supported by grants from the Medical Research Council [G0701757]; and the Wellcome Trust [084840]; with contributions from the Economic and Social Research Council and Department of Health. The web-panel survey was funded by a supplementary grant from the Wellcome Trust. We thank the study participants in Natsal-3 and in the web-panel survey, the team of interviewers at NatCen Social Research, and the researchers and programmers at the market research agency that carried out the web-panel survey.

Copyright

© the authors 2019. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (CC BY 4.0)

Introduction

For several decades, traditional interviewer-administered surveys have been subject to increasing costs and difficulties (such as achieving a high response rate and lengthy, resource-intensive data collection periods)(1). In contrast to these traditional methods, online surveys promise reduced costs and quicker turnaround. As such, there has been dramatic growth in the use of online surveys for market research and opinion polling(2). Despite this, they have not been widely used for collecting epidemiological or surveillance data, due to concerns about their representativeness.

This difference in cost and other difficulties (such as recruitment periods and response rate) can be even more dramatic for some population groups considered “hard-to-reach” in survey research. Groups can be considered “hard-to-reach” because: they make up a small proportion of the general population, such as ethnic or linguistic minorities, drug users and gay, bisexual and other men-who-have-sex-with-men (MSM); members of the population who are hard to identify, such as those who have condom-less sex with multiple partners; members of the population who may not wish to disclose that they belong to a particular group due to stigmatisation or criminalisation of their behaviour, such as illicit drug users and those who sell sex; or because sampling frames for certain groups can be difficult to construct, such as for those who are highly mobile or are homeless(3, 4). Minority groups are represented in small numbers, even in large surveys and it is difficult and costly to ‘boost’ the sample sizes of such groups using probability-sampling methods. There is considerable interest in developing more cost-effective methods of collecting data, and of increasing sample sizes for hard-to-reach groups. Web-panel surveys (WPSs) could provide a viable, cost-effective means of boosting sample sizes of these groups if the panel contains members of these “hard-to-reach” groups, and if they can provide unbiased estimates(2, 5).

A small number of web-panels in the United States (US) and Europe use probability-based sampling methods but are extremely expensive to set up(6-8). Most web-panels comprise self-selected volunteers recruited using methods such as email databases and online advertisements. The majority of WPSs rely on quota sampling from volunteer web-panels run by market research companies. Research from the US and Europe has shown that web-panels have problems with coverage, sampling and non-response biases. WPS response rates are often very low, rarely reported and may be difficult to calculate depending on how web-panel recruitment is designed(9-12). Both sampling methods (e.g. sampling frame) and recruitment/data collection mode (e.g. face-to-face, telephone, web) have distinct implications for data quality and cost(13). Previous research has shown that volunteer web-panel surveys tend to give biased results for key estimates at the population level, in comparison to well-designed probability sample surveys(14-19). However, there is little research on how WPSs compare to probability sample surveys for groups considered “hard-to-reach” in survey research. Minority ethnic groups and sexual identity groups can be “hard-to-reach” in traditional face-to-face surveys and are often represented in small numbers, even in large surveys of the general population. Hard-to-reach and minority groups are also often those at higher risk for harmful sexual behaviours and adverse sexual health outcomes, such as condom-less sex with multiple partners and higher prevalence of STI diagnoses(20-22).

This paper aims to establish whether WPSs could provide a viable means of boosting sample sizes of two particular “hard-to-reach” groups (people of Black African ethnicity and gay men) for a sexual health survey, and the extent of bias found in the WPS. We compare socio-demographic characteristics and estimates of the prevalence of key sexual behaviours and attitudes among these groups from a WPS to reference data including from a large, interviewer-administered, national probability sample survey (the third National Survey of Sexual Attitudes and Lifestyles (Natsal-3)). We also present summary statistics measuring the performance of the WPS compared to Natsal-3 in terms of sexual attitudes and behaviours.

Methods

Participants and procedures

Full details of the methods used in Natsal-3 have been reported elsewhere (23, 24). Briefly, Natsal-3 is a stratified probability sample survey of 15,162 women and men aged 16–74 years in Britain interviewed between September 2010 and August 2012. The estimated overall response rate was 57·7% and the cooperation rate was 65·8% (of all eligible addresses contacted). In Natsal-3, participants were interviewed with a combination of computer-assisted personal interviewing (CAPI, in which the interviewer reads the questions and records the answers), comprising questions on demographics, first heterosexual sex and attitudes, and computer-assisted self-interviewing (CASI, in which the participant completes the survey themselves on the laptop computer), comprising questions on more sensitive behaviours including same-sex sex. A subset of approximately 130 Natsal-3 questions was included on a WPS conducted in 2012 by a well-known survey organisation with a large volunteer web-panel in the United Kingdom (but geographical reach limited to Britain for the purpose of this study). The wording of the questions was identical, except where changes in format were required, for example, where show cards illustrating letters corresponding to response options were used in Natsal-3.

Participants aged 18-44 years who were already members of the web-panel, were recruited for the WPS either through a general population (non-targeted) sample or two independent targeted boost samples. One boost sample was designed to increase the sample size of gay men, the other was designed to increase the sample of those reporting black African ethnic origin. Each targeted “boost” sample was selected using information already held by the survey organisation about individual participants. For both the non-targeted and targeted web-panel samples the WPS company used basic quotas (age within gender). The quotas for age by gender were set with reference to Office for National Statistics (ONS) mid-year 2010 population estimates. For the black African boost sample, quotas were set for age group (18-24, 25-34 and 35-44 years) within gender. For gay men, quotas were set to obtain approximately equal numbers in three age groups (18-24, 25-34 and 35-44 years). Full details of the WPS methods have been previously published(19). The response rate for the WPS, using either targeted or non-targeted recruitment, was not supplied by the WPS company. It is also not always clear what WPS response rates mean given the voluntary nature of web-panels. For these analyses we combined the boosted samples with corresponding group members interviewed as part of the general population sample.

Questions in the WPS were identically worded, and included in the same order as in Natsal-3. However, a number of questions relating to participants’ health were aimed at the 55-74 years age group in Natsal-3 who were excluded from the WPS. These questions were excluded from the WPS, so there may have been some changes to the context in the WPS.

We weighted the Natsal-3 data to adjust for unequal probabilities of selection (in terms of age and the number of adults in the eligible age range at an address) and to be broadly representative of the British population compared with 2011 Census figures, although men and London residents were slightly under-represented (25, 26). Therefore, we also applied a non-response post-stratification weight to correct for differences in gender, age, and Government Office Region between the achieved sample and the 2011 Census. We compared data for participants aged 18–44 years in each survey so the age group was common to both surveys. Information about variables that were compared was derived from identically worded questions. Reference (benchmark) data were obtained from the 2011 Census and the Office for National Statistics’ Integrated Household Survey (IHS) for 2011 via special licence access from the UK Data Archive as sexual identity data were not available in the standard IHS datasets. The IHS is a large annual survey (sample size approximately 400,000) used to produce official statistics. The Natsal-3 study was approved by the Oxfordshire Research Ethics Committee A (reference: 09/H0604/27). Participants in Natsal-3 provided oral informed consent for interviews. Participants in the WPS provided implicit consent by participating in the survey after viewing the survey information page.

Overall, 211 men and 318 women of black African ethnicity completed the WPS. Among those of black African ethnicity, 205 men and 316 women were recruited from the targeted boost sampling and 6 and 2 respectively from the non-targeted sampling. In Natsal-3, 84 men and 127 women reported black African ethnicity. In total, 592 gay men completed the WPS with 500 of these recruited through the targeted boost sampling and 92 using the non-targeted sampling method. In Natsal-3, 83 male participants self-identified as gay, and 130 reported sex with another man in the past 5 years (82 male participants reported both measures, i.e. self-identified as gay and reported sex with another man in the past 5 years).

Statistical analyses

We did all analyses with the complex survey functions of Stata (version 13.1) to incorporate weighting, clustering, and stratification of the Natsal-3 data. We present descriptive statistics by gender and self-reported ethnic origin and sexual identity. We used logistic regression to calculate odds ratios to investigate how reporting of key sexual behaviours and attitudes varied by survey. Bias regarding participant socio-demographic characteristics was assessed by comparing the estimates from the WPS and Natsal-3 to external reference data (from the 2011 UK population census and the IHS) using survey-adapted chi-square tests. For the key behavioural and attitudinal measures, Natsal-3 is treated as the benchmark reference data because its results have been widely used within government and academia, and because it is the only probability-based survey measuring these topics in the British population: no independent reference data exist. For gay men in the web survey we present two comparisons. Firstly we compared estimates of socio-demographic, behavioural and attitudinal measures to self-identifying gay men in Natsal-3. In the second we compared these estimates from gay men in the WPS to men who reported sex with another man in the last five years in Natsal-3 but did not necessarily self-identify as gay, the definition of MSM used in previous Natsal publications(22, 27). We were unable to identify MSM who did not also self-identify as gay for a direct comparison with Natsal-3 MSM as the targeted (boost) WPS was only able to invite men who self-identified as gay in basic panel information to participate in the survey.

Three summary measures of the performance of the web survey compared to Natsal-3 were calculated. These were the number of estimates that differed significantly between these surveys (number of estimates compared: BA women=33, BA men=34, gay men=20); the average absolute odds ratio (OR) across the measures studied; and the largest absolute OR (which shows the extent of differences between some of the individual estimates). The average absolute OR for an OR of less than 1 was calculated as 1/OR (e.g. an OR of 0.5 is equates to an absolute OR of 2). The absolute OR reflects the importance of differences across a range of prevalence, from rare to more common. Average absolute ORs and the largest absolute OR were calculated separately for CAPI and CASI and for behaviour and attitudinal questions as survey performance may differ by question type.

Fewer behaviour and attitudinal variables were compared for gay men and MSM than for people of black African ethnicity as those relating to first heterosexual sex were not compared and a smaller number of questions were asked in relation to first sex with a same-sex partner. The performance of the web survey may differ by the mode of question delivery or by question type. We therefore present average and largest absolute ORs separately for Natsal-3 CAPI and CASI questions and for behavioural and attitudinal questions. The absolute OR for an OR of <1 is calculated as 1/OR so an OR of 0.5 equates to an absolute OR of 2.0. As in previous publications, the absolute OR is used in preference to absolute difference to better reflect the importance of differences across prevalence ranging from rare to common(19). The average absolute OR has a lower bound of 1 and is unlikely to be normally distributed so confidence intervals are not provided. However, bootstrapping was used to obtain a standard error for the average and largest absolute ORs.

Role of the funding source

The sponsors of the study had no role in study design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation, or writing of the report. The corresponding author had full access to all the data in the study and had final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication.

Results

Comparing participant characteristics with external reference data

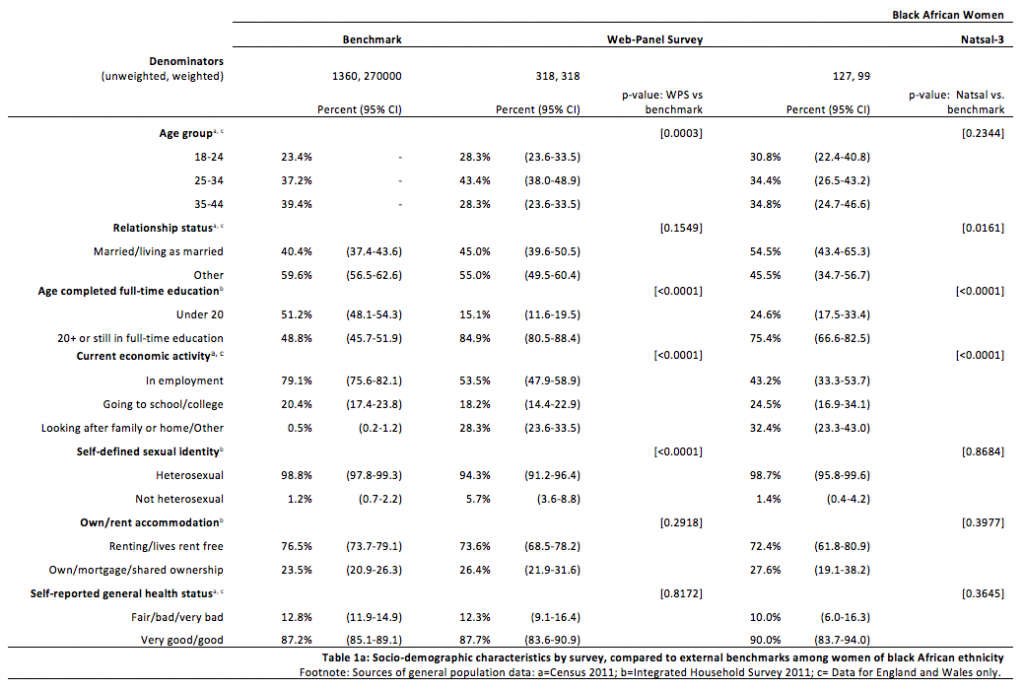

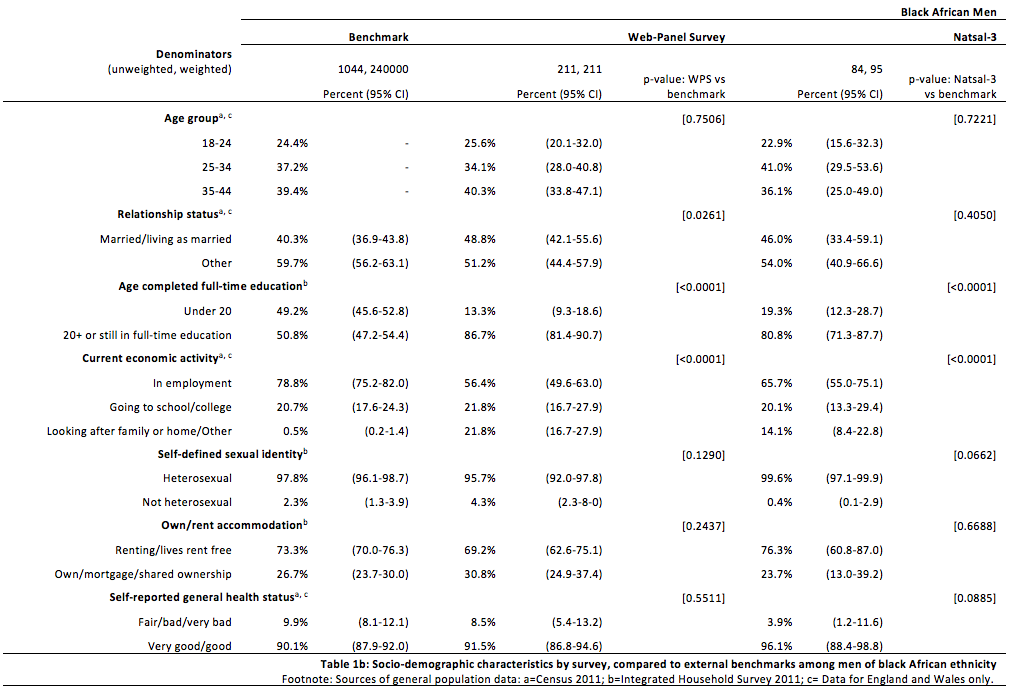

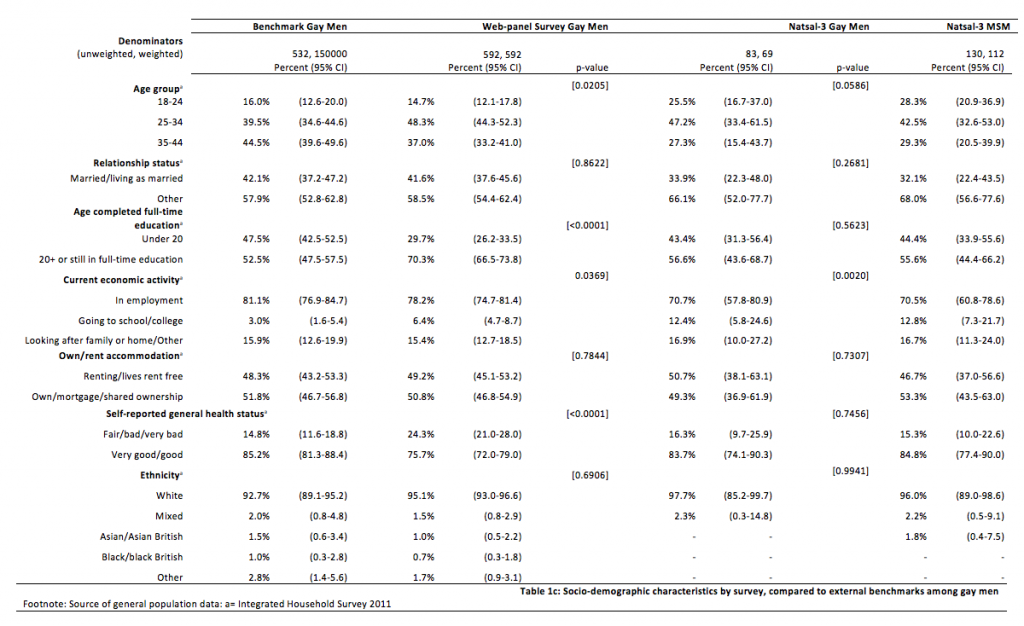

We compared estimates of participant socio-demographic characteristics from the WPS and Natsal-3 with external reference data to assess bias. The characteristics compared were: age group, relationship status, housing tenure, current economic activity and self-assessed general health status. In addition, comparisons were made to reference data in terms of sexual identity (for those of black African ethnicity) and ethnicity (for gay men). Compared with the reference data, women of black African ethnicity reported higher levels of education in Natsal-3 and WPSs, were less likely to be in employment, were more likely to be younger (WPS only) and were more likely to report non-heterosexual identities (WPS only). For men of black African ethnicity similar patterns were seen with higher levels of education and lower levels of employment in Natsal-3 and WPSs and higher reporting of non-heterosexual identities (WPS only). Compared to the reference data and Natsal-3, black African men in the WPS were more likely to report being, or living as, married. Similarly, compared with the reference data, gay men reported higher levels of education in Natsal-3 and WPSs, were less likely to be in employment, were more likely to be younger (WPS only). Among gay men only, a higher proportion reported worse self-reported general health status in the WPS than in Natsal-3 or the reference data. Data on sexual activity are not collected in the Census or IHS so we were unable to identify MSM within these reference data to compare with Natsal-3 and the WPS. These results suggest that both Natsal-3 and the WPS differed from the reference data in terms of education and employment but the clearest difference between the surveys was in reporting of non-heterosexual identities by those of black African ethnicity, with higher reporting in the WPS.

Tables 1 & 2: Socio-demographic characteristics by survey and comparison to reference data

Comparing participant behaviours and attitudes in the WPS with Natsal-3

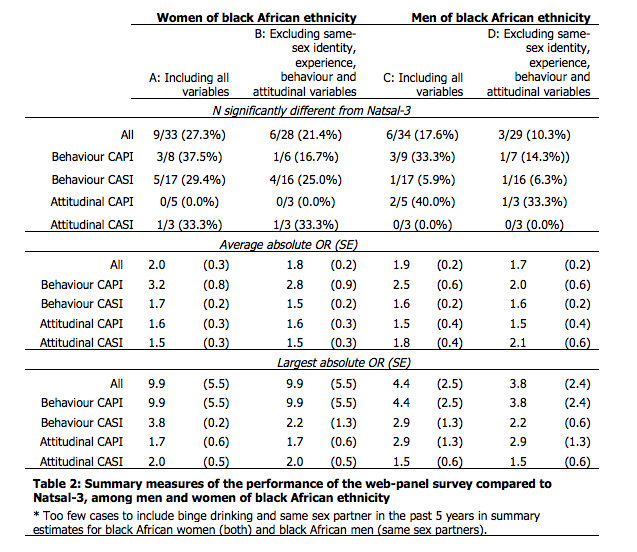

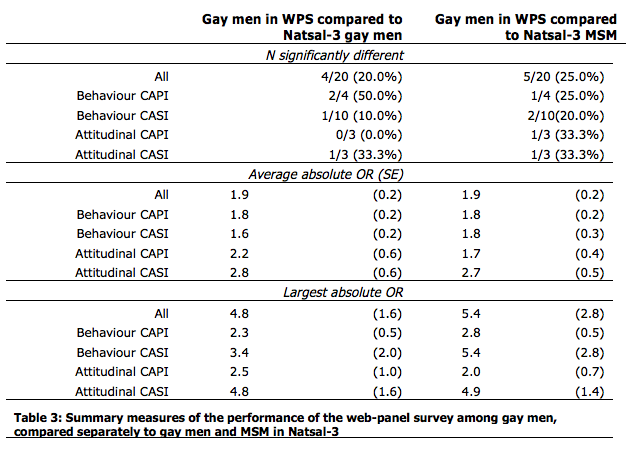

Comparisons between the WPS and Natsal-3 reference data for key estimates are summarised for each group overall and by mode (whether the Natsal-3 question was asked in CAPI or CASI), and question type (whether the question asked about a behaviour or an attitude) (Table 2 and 3).

Approximately 18% of individual estimates differed significantly for men of black African ethnicity (Table 2), 20% for gay men (Table 3), and 27% for women of black African ethnicity (Table 2), the largest group in the Natsal-3 data. For both black African women and men, the average absolute OR was largest for behaviour CAPI questions (3.2 women, 2.5 men); for gay men, the largest average absolute OR was for attitudinal questions asked in CASI (2.8 compared with gay men in Natsal-3). For black African women average absolute ORs were: 1.6 for attitudinal questions asked in CAPI, 1.5 for attitudinal CASI questions, 3.2 for behaviour questions asked in CAPI and for 1.7 for behaviour CASI. For black African men average absolute ORs were: 1.5 for attitudinal questions asked in CAPI, 1.8 for attitudinal CASI questions, 2.5 for behavioural questions asked in CAPI and 1.6 for behavioural questions asked in CASI=1.6. For gay men, average absolute ORs were: 2.2 for attitudinal questions asked in CAPI, 2.8 for attitudinal CASI questions, 1.8 for behavioural questions asked in CAPI to 1.6 for behavioural questions asked in CASI. The largest absolute OR was 9.9 (SE 5.5) among black African women (OR for average alcohol consumption per week, more than recommended – CAPI). However, this large absolute OR reflects very low prevalence of alcohol consumption above recommended levels reported by women of black African ethnicity in Natsal-3 (<1%, n=1). The second largest absolute OR among women of black African ethnicity was 5.5 for same-sex experience (CAPI). For men of black African ethnicity the three largest absolute ORs related to same-sex experience (ever had same sex experience, CAPI), attraction (ever felt sexually attracted to someone of the same sex, CAPI) and sex (ever had same sex experience with genital contact, CASI) reflecting the low prevalence of these reported by black African men in Natsal-3 (1-2%). The largest of these was for same-sex experience at 4.4 (SE 2.5). The largest absolute OR for men of black African ethnicity which was not related to same-sex experience, attraction and sex was 3.0, representing both partners not being equally willing at first (opposite sex) sex (CAPI). The largest absolute OR comparing gay men in the WPS to gay men in Natsal-3 was 5.0 (SE 1.8) for ease of discussing sex with parents at around age 14 years (CAPI attitudinal question).

For CAPI behavioural questions, the average absolute OR and the largest absolute OR were lower for gay men than for men or women of black African ethnicity. Conversely, for attitudinal questions (CAPI and CASI) the average absolute OR and the largest absolute OR were larger for gay men than men and women of black African ethnicity. For men and women of black African ethnicity, average and largest absolute ORs were lower for attitudinal than for CAPI behaviour questions. In contrast, for gay men average absolute ORs were lower for behaviour than attitudinal questions for both CAPI and CASI modes. A larger average absolute OR was found for behavioural questions asked in CAPI compared to those asked in CASI for men and women of black African ethnicity. This pattern was also observed for gay men but the difference between the average absolute OR for behavioural CAPI and CASI questions was much smaller among this group.

Sensitivity Analyses

Estimates of all same-sex identity, attraction and behaviour-related variables differed significantly between the WPS and Natsal-3 for men and women of black African ethnicity. However, the numbers reporting same-sex identity, attraction and behaviour were small in both surveys. We examined whether differences in the summary measures remained when the six estimates relating to same-sex identity, attraction and behaviour were excluded (Columns B and D, Table 2). The average absolute OR was lower for both men and women of black African ethnicity for each mode and question type combination when these variables were excluded, but similar patterns relating to question type and mode remained (Columns B and D, Table 2). Excluding estimates relating to same-sex identity, attraction and behaviour, 21% of individual estimates were significantly different among women of black African ethnicity and 10% among men of black African ethnicity. This indicates that differences between the WPS and Natsal-3 for men and women of black African ethnicity were not limited to questions about same-sex identity, experience, behaviour and attitudes about same-sex partnerships (Table 2).

Gay men in the WPS were identified as eligible based only on whether they self-identified as gay. As a result it is not possible to identify men who had sex with another man in the past 5 years but did not self-identify as gay in the WPS sample. In Natsal-3 this equated to 48 of the 130 men who reported sex with another man in the past 5 years (36.9%). It was also therefore not possible to identify those who identified as gay but had not had sex with a man in the past 5 years, although in Natsal-3, this was just one of the 83 men who self-identified as gay (1.2%). The differences between the WPS and Natsal-3 were similar when MSM, as well as those self-identifying as gay, were included in the Natsal-3 group (Average Absolute ORs, Table 3). For the majority of mode and question type combinations, the largest absolute OR was slightly larger when comparing the web-panel to MSM in Natsal-3 than when comparing to gay men in Natsal-3.

Discussion

Our study compared results for “hard-to-reach” groups between a volunteer WPS and a probability sample survey and showed that, for surveys among the general population, the volunteer WPS is not able to provide scientifically-robust results. A substantial percentage of estimates differed significantly between surveys for gay (20%) and black African men (18%) and women (27%). Patterns in the differences in estimates between the WPS and Natsal-3 by mode, question type and specific group were less clear, but show that the relationship is not straightforward, and that survey mode may have different effects on different hard-to-reach groups.

We identified bias in WPS estimates of key behaviours and attitudes compared to a large, national probability survey (Natsal-3) for two particular groups that are often hard-to-reach in large numbers in traditional household surveys: people of black African ethnicity and gay men. In our study, the WPS boosted these minority groups by selectively recruiting individuals using previously collected information on self-identified ethnicity and sexual identity. Recruiting individuals by screening – i.e., by using information either held on panel members or obtained from upfront screening questions to determine eligibility – is common in WPSs, but means that, unlike probability surveys, including Natsal, they cannot sample groups such as MSM who do not report a non-heterosexual identity. Data from Natsal-3 show that over one-third of MSM did not identify as gay, but reported many similarly increased sexual behaviour risks as MSM who did self-identify as gay, and were more likely to report condom-less sex with two or more partners in the past year than gay-identifying MSM and men who have sex exclusively with women, making them an important group for sexual health research(22). However, comparing gay-identifying MSM in the WPS to gay-identifying MSM in Natsal-3 and all MSM (including those not self-identifying as gay) in Natsal-3 showed only small differences.

Administering surveys online can offer greater anonymity. Whilst this may lead to sensitive behaviours being more commonly reported in the absence of an interviewer(14-17), well-designed traditional CAPI/CASI surveys (that provide robust reassurances of confidentiality), seem able to elicit high quality data on sensitive behaviours(18). Online and CASI surveys are more similar, in terms of how they are completed by participants, than online and CAPI surveys. For each hard-to-reach group, the average absolute OR was higher for behavioural questions asked in the CAPI, rather than the CASI, format in Natsal-3. This indicates mode effects consistent with the idea that fewer differences would be expected for sensitive behavioural questions between an online survey and questions asked in CASI rather than CAPI.

However, even though both CASI and web-surveys are self-administered, they differ in other respects that may influence reporting, such as the presence of an interviewer and perceived privacy. While estimates of same-sex sexual identity, attraction and experience were higher for men and women of black African ethnicity in the WPS than in either CAPI or CASI in Natsal-3, over a range of other variables there was no consistent pattern in reports of sensitive behaviours: for some variables, the differences were quite small, and occasionally showed even lower reporting in the WPS than in Natsal-3 CASI. We found that between (about) 10% and 30% of WPS estimates were significantly different from Natsal-3 CASI estimates for our hard-to-reach groups. Since the self-administered modes (WPS and Natsal-3 CASI) did not yield similar estimates for a significant number of questions, including for some non- sensitive socio-demographic characteristics, it appears that mode effects (i.e., measurement error) cannot fully explain the differences in the estimates between the WPS and Natsal-3 and that selection biases are also likely to be present.

In addition to WPSs, a range of other sampling methods have been used to target hard-to-reach groups. Two-stage sampling, for example, involves ‘screening’ a large sample in order to identify members of the minority target population, followed by a second stage where the sample is selected. While this method can provide a high quality probability sample, it is only viable when the population is relatively stable and easily identifiable, and it can be very expensive and time-consuming, even when using techniques such as ‘focused enumeration’ in order to increase the efficiency of identification(28). Respondent-driven sampling (RDS) is another method that has been developed to sample hard-to-reach groups(29). Initially a small convenience sample of the population is identified, interviewed, and then asked to refer a limited number of others in that population from their social network. Those who are then interviewed from this respondent-recruited sample then become recruiters (of the same limited number of respondents) too. Weights are calculated with the aim of providing unbiased estimates based on the size of each interviewee’s social network. However, individuals with a small social network have a lower probability of being reached by RDS, and refusal rates are difficult to estimate. Furthermore, RDS relies on a number of assumptions that can be very difficult to meet (e.g. that referrals are random, that network sizes are accurately reported), all of which make it difficult to provide representative estimates(30). Our study provides evidence that WPSs may be used to recruit larger samples of self-identified gay men and of ethnic minority groups at a significantly lower resource than door-to-door screening or other sampling methods (such as RDS).

Previous research has found that internet and community surveys often over-estimate levels of sexual risk behaviour due to differences in sample populations when compared to general population probability surveys (31-33). Online surveys, recruiting via volunteer web panels or convenience sampling (advertising), may also be prone to selection bias, such as over-representing gay-identified MSM(27), as they typically use information such as age, gender or self-identified sexual identity to select those eligible to participate. Our WPS used such a selection method, so that MSM who did not identify as gay could not be recruited.

From a sexual health perspective, it may be important for surveys to include those reporting same-sex behaviours who do not identify as gay, lesbian or bisexual, as they may report greater sexual risk behaviours (34, 35). In the event, the appropriate survey design will depend on the precise research question. While convenience samples will recruit larger numbers of a hard-to-reach group, like MSM, they will over-represent those self-identifying as gay and are likely to result in higher reports of risky behaviours(27). On the other hand, large probability sample surveys, such as Natsal, will be able to provide better estimates of sexual behaviours among all MSM or minority ethnic groups, but are limited in the type of analysis that is possible by the much smaller sample sizes of these groups (e.g. it may be difficult to examine associations within groups). The small sample sizes in Natsal-3 of our three hard-to-reach groups may have limited our ability to detect statistically significant differences for individual estimates. However, even with this limited power, around one in five estimates differed significantly for each hard-to-reach group. In addition, probability sample surveys of minority and other hard-to-reach groups, which make up a small proportion of the population, can be prohibitively expensive. WPSs, therefore, may be attractive to those wishing to boost the sample size of minority groups in a general population survey, as well as to those aiming for a large enough sample to permit analyses of within group associations. However, our findings suggest that, stand-alone volunteer WPSs, are likely to give biased estimates. Furthermore, where web-panel surveys have been used to boost numbers obtained in a probability survey, conclusions should be drawn cautiously as selection biases mean WPS participants may not be comparable to those from probability samples. Overall our findings suggest that WPSs are unlikely to satisfactorily replace probability surveys where accurate population-level estimates of sexual (or other) behaviours are required. Furthermore, even where web-panels are able to provide samples of hard-to-reach groups, web-panels may still struggle to provide sufficient numbers for within-group analyses, because these groups comprise a small proportion of the population, and because WPSs often have very low response rates(36).

Strengths and Limitations

One limitation of this study is that it is not possible to determine the extent to which the differences observed between the WPS and Natsal-3 were due to differences in sample composition, sampling method, the mode used for data collection, or a combination of these factors. Another is that, for the key estimates of sexual behaviours and attitudes, it is not possible to say definitively whether Natsal-3 or the WPS provides the most accurate population-level estimates for each hard-to-reach group. Furthermore, small sample sizes for these groups in Natsal-3 limit our ability to detect statistically significant differences in our comparisons with independent reference data for socio-demographic factors and with the WPS for key behavioural and attitudinal characteristics. However, in a related study among the general population, participants in four WPSs were less representative of the general population than Natsal-3 participants on a number of socio-demographic characteristics(19). Differences in sample composition may therefore also explain at least some of the differences observed in the behavioural estimates between the surveys in these hard-to-reach groups. These sample differences are unlikely to be explained by level of internet access and use, as more than 90% of adults aged 18-44 years in Britain used the internet at least once a week and lived in households with internet access at the time of the Natsal-3 survey(37).

The reduced number of questions in the WPS means that, although questions were identically worded and included in the same order as in Natsal-3, there may have been some changes to the context in the WPS. Many of the questions excluded from the WPS related to participants’ health status and were aimed at the 55-74 years age group in Natsal-3 who were excluded from the WPS. Consistent with findings reported elsewhere on responses to attitudinal questions, the self-administered WPS and Natsal-3 CASI showed much greater use of neutral points, such as “don’t know” or “neither agree nor disagree”, when compared with the same (or similar) attitudinal questions in Natsal-3 CAPI(9, 38). However, differences in the presentation of the “don’t know” category for the four CAPI attitudinal questions between Natsal-3 and the WPS may account for at least some of this higher reporting of neutral responses. A “don’t know” option was not included on the show cards used in Natsal-3 (although respondents could spontaneously give “don’t know” as an answer), but was shown as a response category on screen in the WPS. Finally, we were not able to compare Natsal-3 results with those from a web-panel selected using probability sampling methods, because the only probability web-panel in Britain is too small for boosting hard-to-reach groups.

To date, the limited evidence available suggests that volunteer WPS results are likely to differ significantly from survey using face-to-face interviewing and probability sampling methods(39). Another important concern is whether the results obtained would be likely to vary significantly according to which web-panel is used. We used the web-panel from only one survey organisation to provide a boosted sample of our hard-to-reach groups, so we could not examine this. However, a comparison of four different WPSs looking at estimates for the general population found that the results from the four WPSs were significantly different to each other, and that no one WPS consistently performed better than the others across gender, survey mode, or question type(19).

Meaning of the study (Conclusions/Implications)

Hard-to-reach and minority groups are often those at highest risk of harmful sexual behaviours and adverse sexual health outcomes, such as condom-less sex with multiple partners and STI diagnoses, and are therefore of key interest in sexual health research. However, general population probability sample surveys are often only able to recruit small numbers of such groups, precluding analysis of within-group differences. In addition, probability surveys focussing on minority groups can be prohibitively expensive. Online surveys, recruiting via existing web panels or through convenience sampling (via advertising), and community-based surveys, often over-estimate levels of sexual risk behaviour among minority groups due to selection bias of sample members, at least when compared to probability surveys of these groups. Potentially, some WPs may be used to cost-effectively boost sample sizes of some minority groups, making them attractive for research. However, where accurate population-level estimates of sensitive behaviours are required, volunteer web-panel surveys are not satisfactory replacements for probability surveys, as estimates are likely to be biased. Differences between a face-to-face probability sample survey and a WPS for self-completion questions, where mode effects may be similar, suggest greater WPS selection bias. On-going advances in survey methodology are needed to address difficulties in recruiting large enough groups of hard-to-reach and minority groups, but a “simple” shift from interviewer-led probability sampling to online surveys among volunteer web panels is unlikely to be the answer. If probability-sample web-panels become available, future studies could evaluate whether these can be used to obtain accurate population-level estimates for sensitive behaviours in the general population, and whether they are less resource-intensive than interviewer-administered probability surveys for boosting sample sizes of hard-to-reach groups.

References

- Betts P, Lound C. The application of alternative modes of data collection on UK Government social surveys: literature review and consultation with National Statistics Institutes. Office for National Statistics; 2010.

- Callegaro M, Baker R, Bethlehem J, Göritz A, Krosnick J, Lavrakas P. Online panel research: A data quality perspective: Wiley; 2014.

- Bonevski B, Randell M, Paul C, Chapman K, Twyman L, Bryant J, et al. Reaching the hard-to-reach: a systematic review of strategies for improving health and medical research with socially disadvantaged groups. BMC Medical Research Methodology. 2014;14(42).

- Shaghaghi A, Bhopal R, Sheikh A. Approaches to Recruiting ‘Hard-To-Reach’ Populations into Research: A Review of the Literature. Health Promotion Perspectives. 2011;1(2):86-94.

- Prepared for the AAPOR Executive Council by a Task Force operating under the auspices of the AAPOR Standards Committee wmi, Baker R, Blumberg SJ, Brick JM, Couper MP, Courtright M, et al. Research Synthesis: AAPOR Report on Online Panels. Public Opinion Quarterly. 2010;74(4):711-81.

- GfK. Knowledge Panel 2017 [Available from: http://www.gfk.com/products-a-z/us/knowledgepanel-united-states/.

- Institute for data collection and research. LISS Panel [Available from: https://www.lissdata.nl/lissdata/about-panel.

- Blom A, Gathmann C, Krieger U. Setting up an online panel representative of the general population: The German Internet Panel. 2016.

- AAPOR Standards Committee. AAPOR report on online panels. 2010.

- Chang L, Krosnick J. National surveys via Rdd telephone interviewing versus the internet. Comparing sample representativeness and response quality. Public Opinion Quarterly. 2009;73(4):641-78.

- Craig B, Hays R, Pickard S, Cella D, Revicki D, Reeve B. Comparison of US panel vendors for online surveys. Journal of Medical Internet Research. 2013;15(11):e260.

- Yeager D, Krosnick J, Chang L, Javitz H, Levendusky M, Simpser A, et al. Comparing the accuracy of RDD telephone surveys and internet surveys conducted with probability and non-probability samples. Public Opinion Quarterly. 2011;75(4):790-47.

- Clifton S, Prior G, Swales K, Sonnenberg P, Mitchell K, Copas A, et al. Design of a survey of sexual behaviour and attidues in the British population. London: NatCen Social Research; 2018.

- Baer A, Saroiu S, Koutsky L. Obtaining sensitive data through the Web: an example of design and methods. Epidemiology. 2002;13(6):640-5.

- Duffy B, Smith K, Terhanian G, Bremer J. Comparing data from online and face-to-face surveys. International Journal of Market Research. 2005;47(6):615-39.

- Kreuter F, Presser S, Tourangeau R. Social desirability bias in CATI, IVR, and web surveys: the effects of mode and question sensitivity. Public Opinion Quarterly. 2009;72(5):847-65.

- Link M, Mokdad A. Alternative modes for health surveillance surveys: an experiment with web, mail, and telephone. Epidemiology. 2005;16(5):701-4.

- Burkhill S, Copas A, Couper M, Clifton S, Prah P, Datta J, et al. Using the Web to Collect Data on Sensitive Behaviours: A Study Looking at Mode Effects on the British National Survey of Sexual Attitudes and Lifestyles. PloS One. 2016;11(2):e0147983.

- Erens B, Burkhill S, Couper M, Conrad F, Clifton S, Tanton C, et al. Nonprobability Web Surveys to Measure Sexual Behaviors and Attitudes in the General Population: A Comparison With a Probability Sample Interview Survey. Journal of Medical Internet Research. 2014;16(12).

- Wayal S, Hughes G, Sonnenberg P, Mohammed H, Copas A, Gerressu M, et al. Ethnic variations in sexual behaviours and sexual health markers: findings from the third British National Survey of Sexual Attitudes and Lifestyles (Natsal-3). The Lancet Public Health. 2017;2(10):e458-e72.

- Fenton K, Mercer C, McManus S, Erens B, Wellings K, Macdowall W, et al. Ethnic variations in sexual behaviour in Great Britain and risk of sexually transmitted infections: a probability survey. The Lancet. 2005;365(9466):1246-55.

- Mercer C, Prah P, Field N, Tanton C, Macdowall W, Clifton S, et al. The health and well-being of men who have sex with men (MSM) in Britain: Evidence from the third National Survey of Sexual Attitudes and Lifestyles (Natsal-3). BMC Public Health. 2016;16:525.

- Erens B, Phelps A, Clifton S, Mercer C, Tanton C, Hussey D, et al. Methodology of the third British National Survey of Sexual Attitudes and Lifestyles (Natsal-3). Sexually Transmitted Infections. 2013;90(2):84-9.

- Erens B, Phelps A, Clifton S, Hussey D, Mercer C, Tanton C, et al. National Survey of Sexual Attitudes and Lifestyles 3 Technical Report. 2013.

- Office for National Statistics. Census data 2011 [11/05/2015]. Available from: http://www.ons.gov.uk/ons/guide-method/census/2011/census-data/index.html.

- Payne R, Abel G. UK indices of multiple deprivation – a way to make comparisons across constituent countries easier. Health Statistics Quarterly. 2012;53:22-37.

- Prah P, Hickson F, Bonnell C, McDaid L, Johnson A, Wayal S, et al. Men who have sex with men in Great Britain: comparing methods and estimates from probability and convenience sample surveys Sexually Transmitted Infections. 2016;92:455-63.

- Erens B. Designing high quality surveys of ethnic minority groups in the United Kingdom. In: Font J, Mendez M, editors. Surveying ethnic minorities and immigrant populations: methodological challenges and research strategies. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press; 2013. p. 45-67.

- Heckathorn D. Respondent-Driven Sampling: A New Approach to the Study of Hidden Populations. Social Problems. 1997;44(2):174-99.

- White R, Lansky A, Goel S, Wilson A, Hladik W, Hakim A, et al. Respondent driven sampling—where we are and where should we be going? Sexually Transmitted Infections 2012;88:397-9.

- Dodds J, Mercer C, Mercey D, Copas A, Johnson A. Men who have sex with men: a comparison of a probability sample survey and a community based study. Sexually Transmitted Infections. 2006;82:86-7.

- Evans A, Wiggins R, Mercer C, Bolding G, Elford J. Men who have sex with men in Great Britain: comparison of a self-selected internet sample with a national probability sample. Sexually Transmitted Infections. 2007;83:200-5.

- Gerver S, Easterbrook P, Anderson M, Solarin I, Elam G, Fenton K, et al. Sexual risk behaviours and sexual health outcomes among heterosexual black Caribbeans: comparing sexually transmitted infection clinic attendees and national probability survey respondents. International Journal of STD and AIDS. 2011;22(2):85-90.

- Mercer CH, Bailey JV, Johnson AM, Erens B, Wellings K, Fenton KA, et al. Women Who Report Having Sex With Women: British National Probability Data on Prevalence, Sexual Behaviors, and Health Outcomes. American Journal of Public Health. 2007;97(6):1126-33.

- Dewaele A, Caen M, Buysse A. Comparing survey and sampling methods for reaching sexual minority individuals in Flanders. Journal of Official Statistics. 2014;30(2):251-75.

- Vanwesenbeeck I, Bakker F, Gesell S. Sexual Health in the Netherlands: Main Results of a Population Survey Among Dutch Adults. International Journal of Sexual Health. 2010;22(2):55-71.

- Office for National Statistics. Internet Access – Households and Individuals, 2012. Office for National Statistics; 2012.

- Heerwegh D, Loosveldt G. Face-to-face versus web surveying in a high-internet-coverage population. Differences in response quality. Public Opinion Quarterly. 2008;72(5):836-46.

- Cabinet Office. Community Life Survey: Summary of web experiment findings. 2013.