Published online Sep 26, 2019. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v7.i18.2666

Peer-review started: April 19, 2019

First decision: July 10, 2019

Revised: July 26, 2019

Accepted: August 27, 2019

Article in press: August 26, 2019

Published online: September 26, 2019

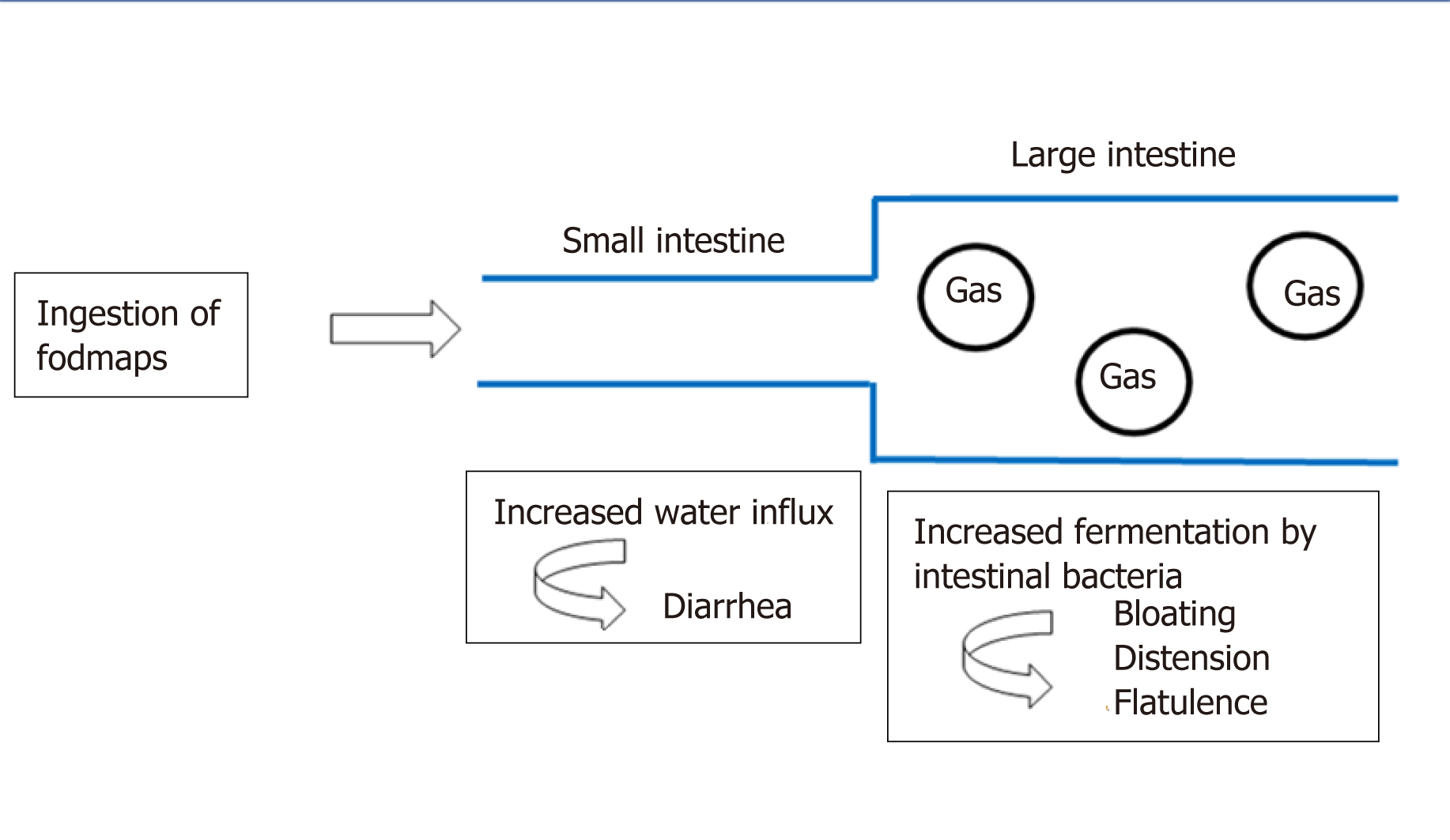

Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) is a lifelong condition with a high prevalence among children and adults. As the diet is a frequent factor that triggers the symptoms, it has been assumed that by avoiding the consumption of fermentable oligosaccharides, disaccharides, monosaccharides and polyols (FODMAP), the symptoms might be improved. Therefore, in the past decade, low FODMAP diet has been intensively investigated in the management of IBS. The capacity of FODMAPs to trigger the symptoms in patients with IBS was related to the stimulation of mechanoreceptors in the small and large intestine. This stimulation appears as a response to a combination of increased luminal water (the osmotic effect) and the release of gases (carbon dioxide and hydrogen) due to the fermentation of oligosaccharides and malabsorption of fructose, lactose and polyols. Numerous studies have been published regarding the efficacy of a low FODMAP diet compared to a traditional diet in releasing the IBS symptoms in adults, but there are only a few studies in the juvenile population. The aim of this review is to analyze the current data on both low FODMAP diet in children with IBS and the effects on their nutritional status and physiological development, given the fact that it is a restrictive diet.

Core tip: Irritable bowel syndrome is one of the most studied entities among the functional gastrointestinal disorders. The relationship between fermentable oligosaccharides, disaccharides, monosaccharides and polyols (FODMAP) and gastrointestinal symptoms was demonstrated both in adults and children. Published studies showed that a low-FODMAP diet is effective for the management of abdominal pain and bloating sensations in most children and adults with irritable bowel syndrome. The children’s nutritional status during a long time restrictive FODMAP diet is not sufficiently assessed.

- Citation: Fodor I, Man SC, Dumitrascu DL. Low fermentable oligosaccharides, disaccharides, monosaccharides, and polyols diet in children. World J Clin Cases 2019; 7(18): 2666-2674

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v7/i18/2666.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v7.i18.2666

Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) is often a chronic condition with a high prevalence in children and adults worldwide. Symptoms of IBS have been identified in 8%-25% of children, based on large studies on both schooled and community children, and up to 66% of them will present with IBS as adults[1]. Using the Rome III criteria, studies concluded that there is approximately a similar prevalence of IBS in children in different geographical settings[1]. In the Mediterranean area of Europe, the prevalence is 4% in the age group 4-10 years and 5.6% in the 11-18 years age group[2]. In the United States, the IBS prevalence in children was established using parental reports, and ranged from 2.8% to 5.1%[3,4], whereas in Colombia the prevalence was of 4.8%[5], and in Sri Lanka it was 5.4%[6]. In contrast, the prevalence of pediatric IBS in China, Nigeria and Turkey is very high, at 13.25%[7], 16%[8] and 22.6%, respectively[9], which may be due to a different interpretation of the gastroenterological symptoms among different cultures[10].

IBS is defined, based on the criteria established by the Rome Foundation IV, as an abdominal discomfort or pain associated with defecation or disordered defecation for at least 2 mo prior to diagnosis[11].

The pathophysiology of IBS is known from studies in adults. The present concept of IBS is based on an alteration of the brain-gut axis, a bidirectional circuit of communication between the gut and the brain, leading to visceral hyperalgesia and followed by disability[10,12]. Similar to adults, psychosocial events and distress (anxiety, depression, anger, impulsiveness) in children influence visceral hypersensitivity[13-15], but some patients assign the somatic hyperalgesia and symptoms to the diet composition[16-18]. A very recent meta-analysis found post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) to be a significant risk factor for IBS (pooled odds ratio 2.80, 95%CI: 2.06-3.54, P < 0.001), as an exaggerated stress response that can increase visceral hypersensitivity of the gut[19].

Between the factors that can influence IBS symptoms or disease evolution, food was one of the most extensively studied, with approximately 60% of IBS patients claiming that certain foods exacerbate their symptoms[20]. Certain food products can generate gastrointestinal symptoms, such as diarrhea, abdominal bloating, discomfort and flatulence, and that was the reason why patients with IBS were advised to restrict the intake of some aliments. The most common foods that can induce such symptoms are milk and other dairy products, legumes and pulses, cruciferous vegetables, some fruits (apples, cherries) and grains (wheat, rye)[21,22].

From this point-of-view, the most incriminated components are the highly fermentable short-chain carbohydrates, which are slowly absorbed or not digested in the small intestine, leading to the distension of the lumen. These were named in 2005 by the Monash group as fermentable oligosaccharides, disaccharides, monosaccharides and polyols (FODMAP) in a paper regarding the link between the western diet (rich in FODMAPs) and the lifestyle in Crohn’s disease patients[23].

After the initial publication of “the FODMAP hypothesis”, an intensive research program started that included the mode of action, extensive analysis of food components, development of cut-off levels (in order to define what a low-FODMAP is), identification of potential side-effects, and, last but not least, the application of the diet in other situations such as IBS, inflammatory bowel disease and functional dyspepsia.

Since 2005, numerous studies have been published regarding the efficacy of a low FODMAP diet compared to a traditional diet in releasing IBS symptoms in adults[24-35]. Several questions still remain regarding this dietary treatment, and thus more randomized controlled studies are needed in order to clearly establish the low-FODMAP diet as the first line therapy method of IBS[36].

Regarding the evaluation of the low FODMAP diet in children with IBS, the first pediatric study was published in 2014. In this small open label pilot study, performed in Texas, United States, the potential benefit of a low FODMAP diet was compared to baseline (the usual diet of the child) in reducing the frequency of abdominal pain. The lowering of mean and maximum pain severity and pain limiting activities in children with IBS was demonstrated for a subset of children with IBS, but the differences between pre- and post-diet symptoms were not statistically significant[37].

In this review, we aim to analyze the published data regarding the implication of a low FODMAP diet in children with IBS, and to discuss the positive or negative effects on the nutritional status and on the physiological development, given that this is a restrictive diet.

The capacity of FODMAPs to induce lowering of symptoms in patients with IBS was related to the stimulation of mechanoreceptors in the small intestine, as a response to a combination of increased luminal water (the osmotic effect) and the release of gases (carbon dioxide and hydrogen) from the fermentation of oligosaccharides and malabsorption of fructose, lactose and polyols[18] (Figure 1).

Based on the length of the carbohydrate chain, different subtypes of FODMAPs were described[38]:

(1) The oligosaccharides are the carbohydrates with the longest chain length and can be found in wheat, rye, legumes, nuts, onion and garlic. They are malabsorbed because there is no capable enzyme to break them down[39,40], resulting in a high fermentation process and gas production in the colon. This plays a significant role in excessive bloating, leading to abdominal pain and flatulence in patients with IBS[41].

(2) The monosaccharide FODMAP is fructose, the smallest carbohydrate, known as fruit sugar (apple, pear, watermelon, mango, honey, but also sweeteners)[42]. Fructose distends the small intestine due to its capacity to draw water into the lumen, a highly osmotic effect, resulting in abdominal pain and bloating[38]. In high quantities, fructose can lead to diarrhea and altered motility. In a study from 1978, a fructose-free diet “cured” four patients with long-standing diarrhea and colics[43], thus its removal from the diet could be efficacious in some cases[44].

(3) In addition, the polyols, such as mannitol and xylitol, are most commonly found in apples, pears and cauliflowers, but also in artificial sweeteners[38]. Their behavior in the intestine is similar to fructose, creating an osmotic effect due to their slow absorbance in the small bowel, which can induce gastrointestinal symptoms[27].

In 2018, Chumpitazi et al[45] analyzed some food products commercialized in the United States, foods frequently consumed by children and potentially low in carbohydrates, in order to include them in a future pediatric clinical trial. The selected food was provided from grocery stores, and contained a mixture of fresh fruit (banana, grapes, pineapple, strawberry and tomato), beverages (simple lemonade, cranberry juice, sweet tea), dairy products, grains and cereals, snacks (pretzels, potato chips, fries), peanut butter, and condiments (mustard, mayonnaise). They excluded foods that were suspected to have excessive FODMAP content, such as whole dairy milk, and also meats due to a uniformly low carbohydrate content. They concluded that all fruit contained fructose, but the glucose content was higher in all of them (glucose facilitates fructose absorption in vivo[46]); lactose was present in butter and cheese products; all of the beverages analyzed contained fructose and fructooligosaccharides with no marked label for this FODMAP; the three gluten-free products evaluated contained more fructose than glucose and fructooligosaccharides; all of the snacks had excess fructose; the condiments were FODMAP free.

In the United States, but also in Europe, there is a lack of food products clear of FODMAP contents, which makes both following a low-FODMAP diet and incorporating FODMAP dietary interventions challenging.

Dietary education became complex in the absence of low-FODMAP diet food lists available in the United States (and Europe). Also, the FODMAP content and the patient’s cultural dietary preferences in food products may differ from country to country[47,48]. McMeans et al[47] analyzed three low-FODMAP dietary guidance food lists, available on the internet since May 2015, which contained more than 150 specific food items and dietary recommendations. They were classified into three categories: full restriction (not allowed at all), partial restriction (small amount allowed) and no restriction. The conclusion was that the lists are often discordant (lack of overlap in > 50%), and the lists do not provide guidance on how to combine food with FODMAP content from different categories. Food products with high and low FODMAP content, more frequently consumed by children, are displayed in Table 1[47].

| Food type | High-FODMAP content | Low-FODMAP content |

| Vegetables | Green peas, leek, mushrooms, cauliflower | Eggplant, green beans, capsicum, carrot, cucumber, lettuce, potato, tomato, zucchini |

| Fruits | Apples, cherries, dried fruit, mango, nectarines, peaches, pears, plums, watermelon | Cantaloupe, grapes, kiwi (green), mandarin, orange, pineapple, strawberries |

| Dairy and alternatives | Cow’s milk, ice cream, yoghurt | Feta cheese, hard cheeses, lactose-free milk |

| Protein | Most legumes/pulses, some marinated meats/poultry/seafood, some processed meats | Eggs, plain cooked meats/poultry/seafood |

| Breads and cereals | Wheat/rye/barley-based breads, breakfast cereals, biscuits and snack products | Corn flakes, oats, quinoa flakes, quinoa/rice/corn pasta, rice cakes |

| Sugars/sweeteners and confectionary | honey | Dark chocolate, maple syrup, rice malt syrup, table sugar |

| Nuts and seeds | Cashews, pistachios | Macadamias, peanuts, pumpkin seeds, walnuts |

The low FODMAP diet involves three phases: a strict low FODMAP diet for the first 2-6 wk, followed by a reintroduction phase in the following 6-8 wk, then the individualized diet phase, which implies the consumption of well-tolerated food for longer periods of time[49].

Despite extensive data outlining the restriction of FODMAP (first phase) and the symptomatic benefits in adult patients with IBS in approximately 70%-86% of cases[50,51], few studies on the pediatric population have been published[37,52]. In 2015, Chumpitazi et al[37], evolving from a pilot study and starting from the idea that the low FODMAP diet can ameliorate the gastrointestinal symptoms in adults with IBS within 48 hours, conducted and published the results of a randomized clinical trial of a low FODMAP diet in children with IBS[52]. They enrolled 52 children with IBS, aged 7-17 years, who met the Rome III criteria for pediatric IBS. The patients ingested their usual diet in the first 7 d, named the baseline period. Following the baseline period, the children were provided with either a low FODMAP or a typical American childhood diet (TACD) for 48 h, and then they returned to their habitual diet for 5 d (wash-out period) before crossing over. Thirty-three children completed both arms of the crossover trial, and were found to have fewer daily abdominal pain episodes during the low FODMAP diet as compared to the TACD and baseline[52].

In the past years, microbiome studies and metabolite profiling became intensively researched[53]. In a pediatric study, Chumpitazi et al[52] evaluated if gut microbiome biomarkers at baseline could predict the response to a low-FODMAP diet, based on the frequency of the abdominal pain. They concluded that the responder group (subjects with 50% decrease in the intensity of abdominal pain) had an increased abundance of Bacterioides, Ruminococcus and Faecalibacterium prausnitzii on baseline, indicators of intestinal health[52]. They also have greater carbohydrate fermentative capacity, which may serve as a biomarker for good responders to the FODMAP restrictive diet.

The second phase of the diet, the reintroduction phase, was less studied both in the child and adult population[54], generally less than a 6 wk period. In order to increase the dataset based on this second phase, blind, randomized, longer-term and interventional studies must be designed[53]. In only one study[55] published as an abstract, the second phase of the low-FODMAP diet was designed as a gradual reintroduction of food during a 6-18 mo period. A follow-up questionnaire was applied to 100 patients regarding their gastrointestinal symptoms (abdominal pain, bloating, flatulence, borborygmi, urgency, sensation of incomplete evacuation and lethargy), and the authors concluded that 62% of patients had satisfactory relief on the diet. Further on, 44/62 patients continued to have satisfactory relief at 1 year following the reintroduction phase, with 42 patients still avoided high-FODMAP foods at least 50% of the time.

Adults with IBS (especially women) often identify food components as triggers of their gastrointestinal symptoms, especially dairy products, fried and fatty foods, foods rich in biogenic amines (wine, beer, cheese, salami) and histamine-releasing products (milk, pork, wine, beer), thus lowering their quality of life[56-60]. A cross-sectional study was performed as a questionnaire and prospective dairy data collected from 2008-2014 by Chumpitazi et al[61], regarding the relationship between self-perceived food intolerance and the severity of IBS symptoms; in total, 154 children meeting the Rome III criteria for pediatric IBS and 32 healthy controls (HS), aged 7-18 years, were recruited. They concluded that more children with IBS versus HS (143/154, 92.9% vs 20/32, 62.5%) identified at least one self-perceived food intolerance and avoided more foods, but these self-perceived intolerances were poorly associated with abdominal pain frequency or the degree, somatization, anxiety, functional disability and decreased quality of life[61].

Twelve papers (six cohort studies and six randomized controlled trials) were included in a recent meta-analysis[62] regarding the effects of the FODMAP diet on IBS patients, the differences between low-FODMAP diet and traditional IBS diet, and high-FODMAP diet versus low-FODMAP diet. The authors concluded that patients on a low-FODMAP diet had a statistically significant lower number of episodes of abdominal pain, bloating and stool emission.

Despite intense research on low-FODMAP diet and its mechanisms of action in patients diagnosed with IBS, especially in the child population, many questions still need to be answered, especially regarding the diet’s implementation in the clinical setting[49].

The national guidelines recommend the diet be supervised by a specialized dietician[38], a recommendation related especially to the presence of a large number of educational materials on the internet, which are often incorrect or incomplete[63]. The newest trends are to use nutrition and health-related applications for smartphones, the Monash University Low FODMAP diet software application being the second highest one recommended by dietitians or self-initiated by patients[64]. Even if the software applications are easy to use and user-friendly, they should only be considered as a helpful tool for following the dieticians’ recommendations and care, but are not a replacement for health professional visits[65].

IBS is a lifelong condition that decreases children’s quality of life and increases school absence[66], but Chumpitazi et al[52] concludes that a low-FODMAP is efficient for symptoms control in children (Table 2).

| Ref. | Study design | Duration | n | Intervention | Results |

| Chumpitazi et al[37] (2014) | Pilot study | 7 d | 8 | One-wk LFSD | Pain frequency, pain severity and pain-related interference with activities decreased during a LFSD |

| Chumpitazi et al[52] (2015) | Randomized clinical trial | 7 d baseline period, followed by a low-FODMAP or TACD diet for 48 h and baseline diet for another 5 d | 33 | Cross over low-FODMAP diet vs TACD | Less abdominal pain during low-FODMAP diet vs TACD |

Given that the diet involves a strict restriction of a large variety of food, when applied to children, several questions regarding the caloric intake and the nutritional status were raised[49]. In the last years, researchers focused on gut microbiota and its relationship to gastrointestinal symptoms in IBS-diagnosed patients. Microbiota with a greater saccharolytic capacity was suggested to be a biomarker for good responders to FODMAP avoidance[52], but more studies are needed. Resistant starch, non-starch polysaccharide, polyphenols and oats are not restricted on the low-FODMAP diet, and these dietary constituents remain relatively undigested in the gut, and have been linked to favorable effects on both the gut microbiota and IBS symptoms[67,68].

Up to 40% of patients suffering from IBS also have psychological disorders including depression and anxiety[69]. Therefore, disordered eating behaviors have been increasingly recognized, especially in adolescents[70]. A better screening for altered eating behaviors should be performed in adolescents with IBS, both prior and during dietary implementation[71].

The low-FODMAP diet is effective in the management of abdominal symptoms in most children and adults diagnosed with IBS. There are still many gaps to be filled regarding the implementation of the diet in clinical practice, the long-term effects related to the nutritional status, a detailed food quantification of FODMAP written on labels, and detailed dietary food lists, along with the impact on the quality of life and overall human health.

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country of origin: Romania

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Adibi P, Ng QS S-Editor: Gong ZM L-Editor: Filipodia E-Editor: Zhou BX

| 1. | Chumpitazi BP, Weidler EM, Czyzewski DI, Self MM, Heitkemper M, Shulman RJ. Childhood Irritable Bowel Syndrome Characteristics Are Related to Both Sex and Pubertal Development. J Pediatr. 2017;180:141-147.e1. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 10] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Scarpato E, Kolacek S, Jojkic-Pavkov D, Konjik V, Živković N, Roman E, Kostovski A, Zdraveska N, Altamimi E, Papadopoulou A, Karagiozoglou-Lampoudi T, Shamir R, Bar Lev MR, Koleilat A, Mneimneh S, Bruzzese D, Leis R, Staiano A; MEAP Group. Prevalence of Functional Gastrointestinal Disorders in Children and Adolescents in the Mediterranean Region of Europe. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;16:870-876. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 48] [Article Influence: 8.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Lewis ML, Palsson OS, Whitehead WE, van Tilburg MAL. Prevalence of Functional Gastrointestinal Disorders in Children and Adolescents. J Pediatr. 2016;177:39-43.e3. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 149] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 157] [Article Influence: 19.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Saps M, Adams P, Bonilla S, Chogle A, Nichols-Vinueza D. Parental report of abdominal pain and abdominal pain-related functional gastrointestinal disorders from a community survey. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2012;55:707-710. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 42] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Lu PL, Velasco-Benítez CA, Saps M. Sex, Age, and Prevalence of Pediatric Irritable Bowel Syndrome and Constipation in Colombia: A Population-based Study. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2017;64:e137-e141. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 16] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Devanarayana NM, Mettananda S, Liyanarachchi C, Nanayakkara N, Mendis N, Perera N, Rajindrajith S. Abdominal pain-predominant functional gastrointestinal diseases in children and adolescents: prevalence, symptomatology, and association with emotional stress. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2011;53:659-665. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 105] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 96] [Article Influence: 7.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Dong L, Dingguo L, Xiaoxing X, Hanming L. An epidemiologic study of irritable bowel syndrome in adolescents and children in China: a school-based study. Pediatrics. 2005;116:e393-e396. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 67] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 72] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Adeniyi OF, Adenike Lesi O, Olatona FA, Esezobor CI, Ikobah JM. Irritable bowel syndrome in adolescents in Lagos. Pan Afr Med J. 2017;28:93. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 10] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 9. | Karabulut GS, Beşer OF, Erginöz E, Kutlu T, Cokuğraş FÇ, Erkan T. The Incidence of Irritable Bowel Syndrome in Children Using the Rome III Criteria and the Effect of Trimebutine Treatment. J Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2013;19:90-93. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 45] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Devanarayana NM, Rajindrajith S. Irritable bowel syndrome in children: Current knowledge, challenges and opportunities. World J Gastroenterol. 2018;24:2211-2235. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in CrossRef: 53] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 39] [Article Influence: 6.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 11. | Hyams JS, Di Lorenzo C, Saps M, Shulman RJ, Staiano A, van Tilburg M. Functional Disorders: Children and Adolescents. Gastroenterology. 2016;. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 809] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 677] [Article Influence: 84.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 12. | Mayer EA, Labus JS, Tillisch K, Cole SW, Baldi P. Towards a systems view of IBS. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;12:592-605. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 171] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 175] [Article Influence: 19.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Iovino P, Tremolaterra F, Boccia G, Miele E, Ruju FM, Staiano A. Irritable bowel syndrome in childhood: visceral hypersensitivity and psychosocial aspects. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2009;21:940-e74. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 29] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Donovan E, Martin SR, Lung K, Evans S, Seidman LC, Cousineau TM, Cook E, Zeltzer LK. Pediatric Irritable Bowel Syndrome: Perspectives on Pain and Adolescent Social Functioning. Pain Med. 2018;. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 5] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Kumagai H, Yokoyama K, Imagawa T, Yamagata T. Functional dyspepsia and irritable bowel syndrome in teenagers: Internet survey. Pediatr Int. 2016;58:714-720. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 16] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Guo YB, Zhuang KM, Kuang L, Zhan Q, Wang XF, Liu SD. Association between Diet and Lifestyle Habits and Irritable Bowel Syndrome: A Case-Control Study. Gut Liver. 2015;9:649-656. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 42] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 17. | Simrén M, Månsson A, Langkilde AM, Svedlund J, Abrahamsson H, Bengtsson U, Björnsson ES. Food-related gastrointestinal symptoms in the irritable bowel syndrome. Digestion. 2001;63:108-115. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 367] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 351] [Article Influence: 16.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Portincasa P, Bonfrate L, de Bari O, Lembo A, Ballou S. Irritable bowel syndrome and diet. Gastroenterol Rep (Oxf). 2017;5:11-19. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 34] [Article Influence: 4.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Ng QX, Soh AYS, Loke W, Venkatanarayanan N, Lim DY, Yeo WS. Systematic review with meta-analysis: The association between post-traumatic stress disorder and irritable bowel syndrome. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019;34:68-73. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 48] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 67] [Article Influence: 13.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | American College of Gastroenterology Task Force on Irritable Bowel Syndrome; Brandt LJ, Chey WD, Foxx-Orenstein AE, Schiller LR, Schoenfeld PS, Spiegel BM, Talley NJ, Quigley EM. An evidence-based position statement on the management of irritable bowel syndrome. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104 Suppl 1:S1-S35. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 182] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 258] [Article Influence: 17.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 21. | Gibson PR. History of the low FODMAP diet. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;32 Suppl 1:5-7. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 48] [Article Influence: 6.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Englyst KN, Liu S, Englyst HN. Nutritional characterization and measurement of dietary carbohydrates. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2007;61 Suppl 1:S19-S39. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 165] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 169] [Article Influence: 10.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Gibson PR, Shepherd SJ. Personal view: food for thought--western lifestyle and susceptibility to Crohn's disease. The FODMAP hypothesis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2005;21:1399-1409. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 229] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 214] [Article Influence: 11.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Shepherd SJ, Parker FC, Muir JG, Gibson PR. Dietary triggers of abdominal symptoms in patients with irritable bowel syndrome: randomized placebo-controlled evidence. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;6:765-771. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 385] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 363] [Article Influence: 22.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Major G, Pritchard S, Murray K, Alappadan JP, Hoad CL, Marciani L, Gowland P, Spiller R. Colon Hypersensitivity to Distension, Rather Than Excessive Gas Production, Produces Carbohydrate-Related Symptoms in Individuals With Irritable Bowel Syndrome. Gastroenterology. 2017;152:124-133.e2. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 192] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 187] [Article Influence: 26.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Hustoft TN, Hausken T, Ystad SO, Valeur J, Brokstad K, Hatlebakk JG, Lied GA. Effects of varying dietary content of fermentable short-chain carbohydrates on symptoms, fecal microenvironment, and cytokine profiles in patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2017;29. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 119] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 122] [Article Influence: 17.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Yao CK, Tan HL, van Langenberg DR, Barrett JS, Rose R, Liels K, Gibson PR, Muir JG. Dietary sorbitol and mannitol: food content and distinct absorption patterns between healthy individuals and patients with irritable bowel syndrome. J Hum Nutr Diet. 2014;27 Suppl 2:263-275. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 71] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 76] [Article Influence: 6.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Laatikainen R, Koskenpato J, Hongisto SM, Loponen J, Poussa T, Hillilä M, Korpela R. Randomised clinical trial: low-FODMAP rye bread vs. regular rye bread to relieve the symptoms of irritable bowel syndrome. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2016;44:460-470. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 65] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 74] [Article Influence: 9.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Harvie RM, Chisholm AW, Bisanz JE, Burton JP, Herbison P, Schultz K, Schultz M. Long-term irritable bowel syndrome symptom control with reintroduction of selected FODMAPs. World J Gastroenterol. 2017;23:4632-4643. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in CrossRef: 88] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 83] [Article Influence: 11.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Maagaard L, Ankersen DV, Végh Z, Burisch J, Jensen L, Pedersen N, Munkholm P. Follow-up of patients with functional bowel symptoms treated with a low FODMAP diet. World J Gastroenterol. 2016;22:4009-4019. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in CrossRef: 91] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 84] [Article Influence: 10.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Cozma-Petruţ A, Loghin F, Miere D, Dumitraşcu DL. Diet in irritable bowel syndrome: What to recommend, not what to forbid to patients! World J Gastroenterol. 2017;23:3771-3783. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in CrossRef: 98] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 75] [Article Influence: 10.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (5)] |

| 32. | Vincenzi M, Del Ciondolo I, Pasquini E, Gennai K, Paolini B. Effects of a Low FODMAP Diet and Specific Carbohydrate Diet on Symptoms and Nutritional Adequacy of Patients with Irritable Bowel Syndrome: Preliminary Results of a Single-blinded Randomized Trial. J Transl Int Med. 2017;5:120-126. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 13] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Magge S, Lembo A. Low-FODMAP Diet for Treatment of Irritable Bowel Syndrome. Gastroenterol Hepatol (N Y). 2012;8:739-745. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 34. | de Roest RH, Dobbs BR, Chapman BA, Batman B, O'Brien LA, Leeper JA, Hebblethwaite CR, Gearry RB. The low FODMAP diet improves gastrointestinal symptoms in patients with irritable bowel syndrome: a prospective study. Int J Clin Pract. 2013;67:895-903. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 214] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 211] [Article Influence: 19.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Pedersen N, Vegh Z, Burisch J, Jensen L, Ankersen DV, Felding M, Andersen NN, Munkholm P. Ehealth monitoring in irritable bowel syndrome patients treated with low fermentable oligo-, di-, mono-saccharides and polyols diet. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:6680-6684. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in CrossRef: 45] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 39] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Varjú P, Farkas N, Farkas P, Garami A, Szabó I, Illés A, Solymár M, Vincze Á, Balaskó M, Pár G, Bajor J, Szűcs Á, Huszár O, Pécsi D, Czimmer J. Low fermentable oligosaccharides, disaccharides, monosaccharides and polyols (FODMAP) diet improves symptoms in adults suffering from irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) compared to standard IBS diet: A meta-analysis of clinical studies. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0182942. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 87] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 82] [Article Influence: 11.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Chumpitazi BP, Hollister EB, Oezguen N, Tsai CM, McMeans AR, Luna RA, Savidge TC, Versalovic J, Shulman RJ. Gut microbiota influences low fermentable substrate diet efficacy in children with irritable bowel syndrome. Gut Microbes. 2014;5:165-175. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 102] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 106] [Article Influence: 10.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Barrett JS. How to institute the low-FODMAP diet. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;32 Suppl 1:8-10. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 59] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 64] [Article Influence: 9.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Rumessen JJ, Gudmand-Høyer E. Fructans of chicory: intestinal transport and fermentation of different chain lengths and relation to fructose and sorbitol malabsorption. Am J Clin Nutr. 1998;68:357-364. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 75] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 74] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Macfarlane GT, Steed H, Macfarlane S. Bacterial metabolism and health-related effects of galacto-oligosaccharides and other prebiotics. J Appl Microbiol. 2008;104:305-344. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 96] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 191] [Article Influence: 11.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Law D, Conklin J, Pimentel M. Lactose intolerance and the role of the lactose breath test. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010;105:1726-1728. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 45] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | Ikechi R, Fischer BD, DeSipio J, Phadtare S. Irritable Bowel Syndrome: Clinical Manifestations, Dietary Influences, and Management. Healthcare (Basel). 2017;5. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 26] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 43. | Andersson DE, Nygren A. Four cases of long-standing diarrhoea and colic pains cured by fructose-free diet--a pathogenetic discussion. Acta Med Scand. 1978;203:87-92. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 43] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 44. | Johlin FC, Panther M, Kraft N. Dietary fructose intolerance: diet modification can impact self-rated health and symptom control. Nutr Clin Care. 2004;7:92-97. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 45. | Chumpitazi BP, Lim J, McMeans AR, Shulman RJ, Hamaker BR. Evaluation of FODMAP Carbohydrates Content in Selected Foods in the United States. J Pediatr. 2018;199:252-255. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 18] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 46. | Muir JG, Gibson PR. The Low FODMAP Diet for Treatment of Irritable Bowel Syndrome and Other Gastrointestinal Disorders. Gastroenterol Hepatol (N Y). 2013;9:450-452. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 47. | McMeans AR, King KL, Chumpitazi BP. Low FODMAP Dietary Food Lists are Often Discordant. Am J Gastroenterol. 2017;112:655-656. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 15] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 48. | Iacovou M, Tan V, Muir JG, Gibson PR. The Low FODMAP Diet and Its Application in East and Southeast Asia. J Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2015;21:459-470. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 42] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 49. | Mitchell H, Porter J, Gibson PR, Barrett J, Garg M. Review article: implementation of a diet low in FODMAPs for patients with irritable bowel syndrome-directions for future research. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2019;49:124-139. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 43] [Article Influence: 8.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 50. | Gibson PR. The evidence base for efficacy of the low FODMAP diet in irritable bowel syndrome: is it ready for prime time as a first-line therapy? J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;32 Suppl 1:32-35. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 32] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 51. | Nanayakkara WS, Skidmore PM, O'Brien L, Wilkinson TJ, Gearry RB. Efficacy of the low FODMAP diet for treating irritable bowel syndrome: the evidence to date. Clin Exp Gastroenterol. 2016;9:131-142. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 57] [Article Influence: 7.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 52. | Chumpitazi BP, Cope JL, Hollister EB, Tsai CM, McMeans AR, Luna RA, Versalovic J, Shulman RJ. Randomised clinical trial: gut microbiome biomarkers are associated with clinical response to a low FODMAP diet in children with the irritable bowel syndrome. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2015;42:418-427. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 241] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 262] [Article Influence: 29.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 53. | Hill P, Muir JG, Gibson PR. Controversies and Recent Developments of the Low-FODMAP Diet. Gastroenterol Hepatol (N Y). 2017;13:36-45. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 54. | Tuck C, Barrett J. Re-challenging FODMAPs: the low FODMAP diet phase two. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;32 Suppl 1:11-15. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 41] [Article Influence: 5.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 55. | Martin L, van Vuuren C, Seamark L, Williams M, Staudacher H, Irving PM, Whelan K, Lomer MC. OC-104 Long term effectiveness of short chain fermentable carbohydrate (FODMAP) restriction in patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Gut. 2015;64:A51-A52. [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 56. | Böhn L, Störsrud S, Törnblom H, Bengtsson U, Simrén M. Self-reported food-related gastrointestinal symptoms in IBS are common and associated with more severe symptoms and reduced quality of life. Am J Gastroenterol. 2013;108:634-641. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 385] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 390] [Article Influence: 35.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 57. | El-Salhy M, Ostgaard H, Gundersen D, Hatlebakk JG, Hausken T. The role of diet in the pathogenesis and management of irritable bowel syndrome (Review). Int J Mol Med. 2012;29:723-731. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 40] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 58. | Zigich S, Heuberger R. The relationship of food intolerance and irritable bowel syndrome in adults. Gastroenterol Nurs. 2013;36:275-282. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 8] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 59. | Monsbakken KW, Vandvik PO, Farup PG. Perceived food intolerance in subjects with irritable bowel syndrome-- etiology, prevalence and consequences. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2006;60:667-672. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 247] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 240] [Article Influence: 13.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 60. | Gibson PR, Shepherd SJ. Food choice as a key management strategy for functional gastrointestinal symptoms. Am J Gastroenterol. 2012;107:657-66; quiz 667. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 134] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 133] [Article Influence: 11.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 61. | Chumpitazi BP, Weidler EM, Lu DY, Tsai CM, Shulman RJ. Self-Perceived Food Intolerances Are Common and Associated with Clinical Severity in Childhood Irritable Bowel Syndrome. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2016;116:1458-1464. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 27] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 62. | Altobelli E, Del Negro V, Angeletti PM, Latella G. Low-FODMAP Diet Improves Irritable Bowel Syndrome Symptoms: A Meta-Analysis. Nutrients. 2017;9:pii: E940. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 117] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 124] [Article Influence: 17.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 63. | O'Keeffe M, Lomer MC. Who should deliver the low FODMAP diet and what educational methods are optimal: a review. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;32 Suppl 1:23-26. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 46] [Article Influence: 6.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 64. | Sauceda A, Frederico C, Pellechia K, Starin D. Results of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics' Consumer Health Informatics Work Group's 2015 Member App Technology Survey. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2016;116:1336-1338. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 20] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 65. | Chen J, Gemming L, Hanning R, Allman-Farinelli M. Smartphone apps and the nutrition care process: Current perspectives and future considerations. Patient Educ Couns. 2018;101:750-757. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 65] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 45] [Article Influence: 7.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 66. | Youssef NN, Murphy TG, Langseder AL, Rosh JR. Quality of life for children with functional abdominal pain: a comparison study of patients' and parents' perceptions. Pediatrics. 2006;117:54-59. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 208] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 197] [Article Influence: 10.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 67. | Ng QX, Soh AYS, Loke W, Venkatanarayanan N, Lim DY, Yeo WS. A Meta-Analysis of the Clinical Use of Curcumin for Irritable Bowel Syndrome (IBS). J Clin Med. 2018;7:pii: E298. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 46] [Article Influence: 7.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 68. | Duda-Chodak A, Tarko T, Satora P, Sroka P. Interaction of dietary compounds, especially polyphenols, with the intestinal microbiota: a review. Eur J Nutr. 2015;54:325-341. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 336] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 346] [Article Influence: 38.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 69. | Wu JC. Psychological Co-morbidity in Functional Gastrointestinal Disorders: Epidemiology, Mechanisms and Management. J Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2012;18:13-18. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 69] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 80] [Article Influence: 6.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 70. | Satherley R, Howard R, Higgs S. Disordered eating practices in gastrointestinal disorders. Appetite. 2015;84:240-250. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 52] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 57] [Article Influence: 5.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 71. | Reed-Knight B, Squires M, Chitkara DK, van Tilburg MA. Adolescents with irritable bowel syndrome report increased eating-associated symptoms, changes in dietary composition, and altered eating behaviors: a pilot comparison study to healthy adolescents. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2016;28:1915-1920. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 47] [Article Influence: 5.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |