Abstract

Background

Upward economic mobility represents the ability of children to surpass their parents financially and improve their economic status. The extent to which it contributes to socioeconomic disparities in health outcomes remains largely unknown.

Methods

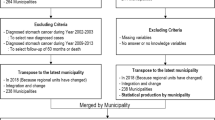

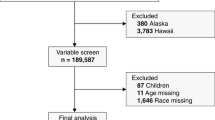

Patients diagnosed with hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) in 2004–2015 were identified from the SEER–Medicare linked database. Information on county-level upward economic mobility was obtained from the Opportunity Atlas, and its impact on early-stage diagnosis (tumor size ≤ 5 cm, no nodal involvement or distant metastases, no major vascular invasion or extrahepatic extension) and receipt of curative-intent treatment (resection, transplantation, or ablation) was examined.

Results

Among 9190 Medicare beneficiaries diagnosed with HCC, the majority were White (64.9%, n = 5965). Overall, 44.7% (n = 4105) of patients were diagnosed with early-stage HCC and 29.7% (n = 2731) underwent curative-intent treatment. While higher upward economic mobility was not associated with HCC diagnosis at an early stage (OR 0.94, 95% CI 0.83–1.06), patients with early-stage HCC from areas of high upward economic mobility had increased odds of undergoing curative-intent treatment (OR 1.25, 95% CI 1.03–1.51). Upward economic mobility had no impact on the likelihood to undergo curative-intent treatment for early-stage HCC among White (OR 1.15, 95% CI 0.91–1.45), Black (OR 1.94, 95% CI 0.85–4.45) or Asian patients (OR 0.77, 95% CI 0.44–1.36). In contrast, non-White patients other than Blacks or Asians diagnosed with early-stage HCC had markedly higher odds of receiving curative-intent treatment if the individual resided in an area characterized by higher versus lower upward economic mobility (OR 2.58, 95% CI 1.50–4.46).

Conclusions

While community-level economic mobility was not associated with stage of diagnosis, it affected the likelihood of undergoing curative-intent treatment for early-stage HCC, especially among minority patients other than Black or Asian patients.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

International Agency for Research on Cancer. Cancer Today. Data visualization tools for exploring the global cancer burden in 2020. Accessed November 3, 2021, https://gco.iarc.fr/today/home

Siegel RL, Miller KD, Fuchs HE, Jemal A. Cancer ctatistics, 2021. CA Cancer J Clin. 2021;71(1):7–33. https://doi.org/10.3322/caac.21654.

Jemal A, Ward EM, Johnson CJ, et al. Annual report to the nation on the status of cancer, 1975–2014, featuring survival. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2017. https://doi.org/10.1093/jnci/djx030.

American Cancer Society. Liver cancer survival rates. Updated January 29, 2021. Accessed November 3, 2021, https://www.cancer.org/cancer/liver-cancer/detection-diagnosis-staging/survival-rates.html#references

Howlander N, Noone AM, Krapcho M, Miller D. SEER Cancer Statistics Review, 1975-2017. 2020. Accessed April 2021. https://seer.cancer.gov/csr/1975_2017/

National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. Hepatobiliary Cancers. Version 5.2021. Updated September 21, 2021. Accessed November 3, 2021, https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/hepatobiliary.pdf

Artinyan A, Mailey B, Sanchez-Luege N, et al. Race, ethnicity, and socioeconomic status influence the survival of patients with hepatocellular carcinoma in the United States. Cancer. 2010;116(5):1367–77. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.24817.

Rich NE, Carr C, Yopp AC, Marrero JA, Singal AG. Racial and ethnic disparities in survival among patients with hepatocellular carcinoma in the United States: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cgh.2020.12.029.

Wong RJ, Kim D, Ahmed A, Singal AK. Patients with hepatocellular carcinoma from more rural and lower-income households have more advanced tumor stage at diagnosis and significantly higher mortality. Cancer. 2020;127(1):45–55. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.33211.

Braveman PA, Cubbin C, Egerter S, Williams DR, Pamuk E. Socioeconomic disparities in health in the United States: what the patterns tell us. Am J Public Health. 2010;100(Suppl 1):S186–96. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2009.166082.

Anyiwe K, Qiao Y, De P, Yoshida EM, Earle CC, Thein HH. Effect of socioeconomic status on hepatocellular carcinoma incidence and stage at diagnosis, a population-based cohort study. Liver Int. 2016;36(6):902–10. https://doi.org/10.1111/liv.12982.

Ha J, Yan M, Aguilar M, et al. Race/ethnicity-specific disparities in hepatocellular carcinoma stage at diagnosis and its impact on receipt of curative therapies. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2016;50(5):423–30. https://doi.org/10.1097/MCG.0000000000000448.

Hoehn RS, Hanseman DJ, Jernigan PL, et al. Disparities in care for patients with curable hepatocellular carcinoma. HPB (Oxford). 2015;17(9):747–52. https://doi.org/10.1111/hpb.12427.

Hoehn RS, Hanseman DJ, Wima K, et al. Does race affect management and survival in hepatocellular carcinoma in the United States? Surgery. 2015;158(5):1244–51. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.surg.2015.03.026.

Chetty R, Hendren N, Kline P, Saez E. Where is the land of opportunity? The geography of intergenerational mobility in the United States. Q J Econ. 2014;129(4):1553–623. https://doi.org/10.1093/qje/qju022.

Mazumder B. Intergenerational mobility in the United States: what we have learned from the PSID. Ann Am Acad Pol Soc Sci. 2018;680(1):213–34. https://doi.org/10.1177/0002716218794129.

Bratberg E, Mazumder J, Nybom B, Schnitzlein M, Vaage K. A comparison of intergenerational mobility curves in Germany Norway Sweden, and the US. Scand J Econ. 2016. https://doi.org/10.1111/sjoe.12197.

Davis JM. The decline in intergenerational mobility after 1980. Stone Center Working Paper Series. 2020;11

Nathan H, Pawlik TM. Limitations of claims and registry data in surgical oncology research. Ann Surg Oncol. 2008;15(2):415–23. https://doi.org/10.1245/s10434-007-9658-3.

Warren JL, Klabunde CN, Schrag D, Bach PB, Riley GF. Overview of the SEER-Medicare data: content, research applications, and generalizability to the United States elderly population. Med Care. 2002. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.MLR.0000020942.47004.03.

Opportunity Insights. Data library. Accessed August 6, 2021, https://opportunityinsights.org/data/

Chetty R, Friedman JN, Hendren N, Jones MR, Porter SR. The opportunity atlas: mapping the childhood roots of social mobility. National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper Series. 2018; doi:https://doi.org/10.3386/w25147

Nathan H, Hyder O, Mayo SC, et al. Surgical therapy for early hepatocellular carcinoma in the modern era: a 10-year SEER-medicare analysis. Ann Surg. 2013;258(6):1022–7. https://doi.org/10.1097/SLA.0b013e31827da749.

Nathan H, Schulick RD, Choti MA, Pawlik TM. Predictors of survival after resection of early hepatocellular carcinoma. Ann Surg. 2009;249(5):799–805. https://doi.org/10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181a38eb5.

Quan H, Sundararajan V, Halfon P, et al. Coding algorithms for defining comorbidities in ICD-9-CM and ICD-10 administrative data. Med Care. 2005;43(11):1130–9. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.mlr.0000182534.19832.83.

Quan H, Li B, Couris CM, et al. Updating and validating the Charlson comorbidity index and score for risk adjustment in hospital discharge abstracts using data from 6 countries. Am J Epidemiol. 2011;173(6):676–82. https://doi.org/10.1093/aje/kwq433.

Azap RA, Hyer JM, Diaz A, Paredes AZ, Pawlik TM. Association of county-level vulnerability, patient-level race/ethnicity, and receipt of surgery for early-stage hepatocellular carcinoma. JAMA Surg. 2021;156(2):197–9. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamasurg.2020.5554.

Adler NE, Glymour MM, Fielding J. Addressing social determinants of health and health inequalities. JAMA. 2016;316(16):1641–2. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2016.14058.

World Health Organization. Social determinants of health. Accessed November 5, 2021, https://www.who.int/health-topics/social-determinants-of-health#tab=tab_1

Azap RA, Diaz A, Hyer JM, et al. Impact of race/ethnicity and county-level vulnerability on receipt of surgery among older Medicare beneficiaries with the diagnosis of early pancreatic cancer. Ann Surg Oncol. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1245/s10434-021-09911-1.

Hyer JM, Tsilimigras DI, Diaz A, et al. High social vulnerability and “textbook outcomes” after cancer operation. J Am Coll Surg. 2021;232(4):351–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2020.11.024.

Daly MC, Duncan GJ, McDonough P, Williams DR. Optimal indicators of socioeconomic status for health research. Am J Public Health. 2002;92(7):1151–7. https://doi.org/10.2105/ajph.92.7.1151.

Wang J, Ha J, Lopez A, Bhuket T, Liu B, Wong RJ. Medicaid and uninsured hepatocellular carcinoma patients have more advanced tumor stage and are less likely to receive treatment. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2018;52(5):437–43. https://doi.org/10.1097/MCG.0000000000000859.

Canary LA, Klevens RM, Holmberg SD. Limited access to new hepatitis C virus treatment under state Medicaid programs. Ann Intern Med. 2015;163(3):226–8. https://doi.org/10.7326/M15-0320.

Wong RJ, Jain MK, Therapondos G, et al. Race/ethnicity and insurance status disparities in access to direct acting antivirals for hepatitis C virus treatment. Am J Gastroenterol. 2018;113(9):1329–38. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41395-018-0033-8.

Farvardin S, Patel J, Khambaty M, et al. Patient-reported barriers are associated with lower hepatocellular carcinoma surveillance rates in patients with cirrhosis. Hepatology. 2017;65(3):875–84. https://doi.org/10.1002/hep.28770.

Singal AG, Li X, Tiro J, et al. Racial, social, and clinical determinants of hepatocellular carcinoma surveillance. Am J Med. 2015;128(1):90 e1-97. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjmed.2014.07.027.

Chetty R, Stepner M, Abraham S, et al. The association between income and life expectancy in the United States, 2001–2014. JAMA. 2016;315(16):1750–66. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2016.4226.

Tan D, Yopp A, Beg MS, Gopal P, Singal AG. Meta-analysis: underutilisation and disparities of treatment among patients with hepatocellular carcinoma in the United States. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2013;38(7):703–12. https://doi.org/10.1111/apt.12450.

Fields GS, Ok EA. The meaning and measurement of income mobility. J Econ Theory. 1996;71(2):349–77.

Darin-Mattsson A, Fors S, Kåreholt I. Different indicators of socioeconomic status and their relative importance as determinants of health in old age. Int J Equity Health. 2017;16(173)

The Bell Policy Center. What is Economic Mobility? Accessed August 19, 2021, www.bellpolicy.org/what-is-economic-mobility

Nathan H, Segev DL, Bridges JF, et al. Influence of nonclinical factors on choice of therapy for early hepatocellular carcinoma. Ann Surg Oncol. 2013;20(2):448–56. https://doi.org/10.1245/s10434-012-2619-5.

Diaz A, Hyer JM, Barmash E, Azap R, Paredes AZ, Pawlik TM. County-level social vulnerability is associated with worse surgical outcomes especially among minority patients. Ann Surg. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1097/SLA.0000000000004691.

Paro A, Dalmacy D, Madison Hyer J, Tsilimigras DI, Diaz A, Pawlik TM. Impact of residential racial integration on postoperative outcomes among medicare beneficiaries undergoing resection for cancer. Ann Surg Oncol. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1245/s10434-021-10034-w.

Zak Y, Rhoads KF, Visser BC. Predictors of surgical intervention for hepatocellular carcinoma: race, socioeconomic status, and hospital type. Arch Surg. 2011;146(7):778–84. https://doi.org/10.1001/archsurg.2011.37.

Mathur AK, Osborne NH, Lynch RJ, Ghaferi AA, Dimick JB, Sonnenday CJ. Racial/ethnic disparities in access to care and survival for patients with early-stage hepatocellular carcinoma. Arch Surg. 2010;145(12):1158–63. https://doi.org/10.1001/archsurg.2010.272.

David R, Collins C. US socioeconomic and racial differences in health: patterns and explanations. Annu Rev Sociol. 1995;21:349–86.

Williams DR, Lavizzo-Mourey R, Warren RC. The concept of race and health status in America. Public Health Rep. 1994;109(1):26–41.

Hardy B, Logan T. Race and the lack of intergenerational economic mobility in the United States. Accessed August 19, 2021, https://equitablegrowth.org/race-and-the-lack-of-intergenerational-economic-mobility-in-the-united-states/

Hardy BL, Logan TD, Parman J. The historical role of race and policy for regional inequality. Place-Based Policies for Shared Economic Growth. 2018.

Chetty R, Hendren N, Jones MR, Porter SR. Race and economic opportunity in the United States: an intergenerational perspective. Q J Econ. 2020;135(2):711–83.

Sonnenday CJ, Dimick JB, Schulick RD, Choti MA. Racial and geographic disparities in the utilization of surgical therapy for hepatocellular carcinoma. J Gastrointest Surg. Dec 2007;11(12):1636-46; discussion 1646. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s11605-007-0315-8

Pinheiro PS, Medina HN, Callahan KE, et al. The association between etiology of hepatocellular carcinoma and race-ethnicity in Florida. Liver Int. 2020;40(5):1201–10. https://doi.org/10.1111/liv.14409.

Maani N, Galea S. The role of physicians in addressing social determinants of health. JAMA. 2020;323(16):1551–2. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2020.1637.

Acknowledgment

None.

Funding

None.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Disclosure

None.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Paro, A., Dalmacy, D., Tslimigras, D.I. et al. Association of County-Level Upward Economic Mobility with Stage at Diagnosis and Receipt of Curative-Intent Treatment among Patients with Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Ann Surg Oncol 29, 5177–5185 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1245/s10434-022-11726-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1245/s10434-022-11726-7