Major depressive disorder (MDD) is often characterised by a chronic and recurrent nature.Reference Eaton, Shao, Nestadt, Lee, Bienvenu and Zandi1,Reference Moffitt, Caspi, Taylor, Kokaua, Milne and Polanczyk2 After the first episode of MDD, there is a 40–60% risk that a person relapses,Reference Eaton, Shao, Nestadt, Lee, Bienvenu and Zandi1,Reference Moffitt, Caspi, Taylor, Kokaua, Milne and Polanczyk2 and this risk rises by 16% following each successive episode.Reference Solomon, Keller, Leon, Mueller, Lavori and Shea3 Ultimately, the cumulative lifetime risk may increase up to 90% after three episodes or more.Reference Eaton, Shao, Nestadt, Lee, Bienvenu and Zandi1,Reference Solomon, Keller, Leon, Mueller, Lavori and Shea3 It is of increasing importance to prevent relapse of depression in clinical practice, given its substantial impact on public health.

International clinical guidelines recommend long-term antidepressant medication beyond 9 months (USA)4 or 2 years (UK)5 for patients with at least two or three previous episodes. Psychological interventions, that is, cognitive–behavioural therapy (CBT) or mindfulness-based cognitive therapy (MBCT), are recommended as an addition to antidepressants for high-risk populations, including people with multiple previous episodes.4,5 In clinical practice, MDD appears to be mostly managed with antidepressant medication alone.Reference Moore, Yuen, Dunn, Mullee, Maskell and Kendrick6 Taking antidepressants long-term is not a panacea. Relapse rates on antidepressants vary by population but can rise to 60% after 24 months.Reference Bockting, Klein, Elgersma, van Rijsbergen, Slofstra and Ormel7 Antidepressant use is associated with side-effects,4,5 and patients might often prefer psychological treatments to continuing antidepressants.Reference McHugh, Whitton, Peckham, Welge and Otto8 Patients who attempt to taper off antidepressants after remission are at an increased risk of depressive relapse.Reference Horowitz and Taylor9

Thus, alternatives to long-term antidepressant use should be explored to optimise outcomes for patients. Recent studies suggest that psychological interventions appear to be effective in reducing the risk of relapse of depression when added to tapering or combined with antidepressants.Reference Bockting, Klein, Elgersma, van Rijsbergen, Slofstra and Ormel7,Reference Guidi, Fava, Fava and Papakostas10,Reference Guidi, Tomba and Fava11 Yet, to the best of our knowledge, a meta-analysis comparing psychological intervention as an alternative or additive to antidepressants alone is lacking. The three reviewsReference Guidi, Fava, Fava and Papakostas10–Reference Biesheuvel-Leliefeld, Kok, Bockting, Cuijpers, Hollon and van Marwijk12 published thus far were conducted on a restricted sample of studies (n = 4) comparing psychological interventions without antidepressants with antidepressants alone,Reference Guidi, Tomba and Fava11 included studies with unmasked (unblinded) outcome assessmentsReference Guidi, Fava, Fava and Papakostas10–Reference Biesheuvel-Leliefeld, Kok, Bockting, Cuijpers, Hollon and van Marwijk12 or did not report on the specific comparison, that is, psychological interventions with or without antidepressants compared with antidepressants alone.Reference Biesheuvel-Leliefeld, Kok, Bockting, Cuijpers, Hollon and van Marwijk12

In this study, we aim to remediate the above limitations and conduct an up-to-date systematic review and meta-analysis to compare the effects of psychological interventions as an alternative (psychological intervention alone) and as an addition to antidepressants (psychological intervention plus maintenance antidepressants) versus long-term antidepressant use on relapse/recurrence in depression.

Method

Search strategy

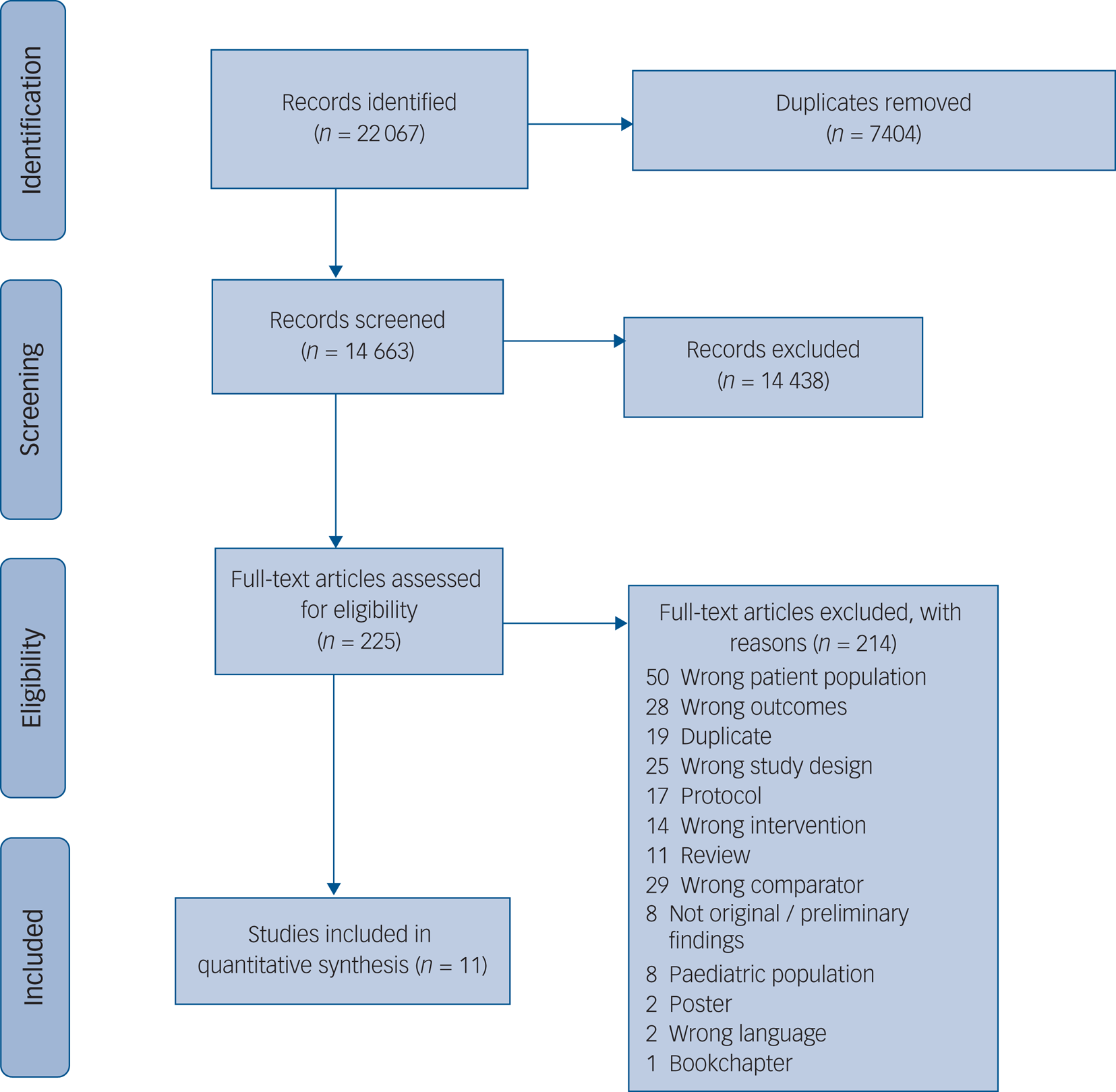

The PRISMA guidance was followed in the reporting of this reviewReference Moher, Shamseer, Clarke, Ghersi, Liberatî and Petticrew13 (PROSPERO ID: CRD42017055301). Search strings were developed with a health sciences librarian (supplementary Appendix, available at https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.2020.198). MeSH terms, Boolean operators and free text were used to identify studies in Embase, the Cochrane Library, PubMed and PsychInfo. The last search was conducted on the 13 October 2019. Covidence14 was used to manage the study screening and selection process. Duplicates were removed before the title and abstract screening. Reference lists and prior meta-analyses were searched for relevant literature. Titles and abstracts were screened independently by J.B., V.Z., E.B. and A.S.. After screening, two independent researchers (J.B. and M.B.) conducted the final inclusion of studies. Disagreements were resolved by consulting a third researcher (C.B.).

Study criteria

Randomised controlled trials (RCTs) with participants aged 18–65 who had at least one prior diagnosis of MDD were included. Studies comparing psychological interventions with and without antidepressants versus antidepressant control were included. For the studies evaluating psychological interventions without antidepressants versus antidepressants alone, psychological interventions could be delivered either on their own or while tapering antidepressants. The participants had to be randomised to a relapse prevention intervention after response, remission or recovery.Reference Bockting, Jarrett, Kuyken and Dobson15,Reference Frank, Prien, Jarret, Keller, Kupfer and Lavori16 Remission was defined as a period of at least 8 weeks during which participants had no or subclinical symptoms (i.e. Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression score ≤7, Beck Depression Inventory-II score ≤13, Patient Health Questionnaire score ≤10).Reference Bockting, Jarrett, Kuyken and Dobson15 Relapse was defined as an increase in symptomatology during remission, and recurrence as an increase in symptomatology during recovery.Reference Bockting, Jarrett, Kuyken and Dobson15,Reference Frank, Prien, Jarret, Keller, Kupfer and Lavori16 In this paper we use relapse to describe both recurrence and relapse. Sequential treatment combinationsReference Bockting, Jarrett, Kuyken and Dobson15 were included provided that participants in the intervention group achieved remission or response, according to the authors of the study. Studies were included if participants’ primary presenting problem was depression (as opposed to depression secondary to other (mental) health conditions). Participants were excluded if they were in active treatment for another mental disorder as classified by DSM-IV.17 Outcome measurement (relapse or recurrence of a depressive episode) had to be conducted by an independent assessor via a clinical diagnostic assessment.

Data extraction

Study data were extracted in a pre-piloted extraction table by three reviewers (J.B., C.M. and M.H.). Discrepancies were discussed and resolved by consensus. Study characteristics, sample characteristics, intervention characteristics (including tapering or continuation of antidepressants), delivery information and the definition of recurrence or relapse were extracted. Extracted outcome data included the length of follow-up, rates of relapse or recurrence in intervention and control group at the last point of follow-up and the hazard ratio (HR) for each relevant comparison.

Risk of bias assessment

Study quality was assessed independently by three reviewers. J.B. and M.B. conducted the risk of bias assessments independently. Six criteria for risk of bias (on nine domains) were used from the risk of bias assessment tool developed by the Cochrane Collaboration.Reference Furlan, Pennick, Bombardier and van Tulder18,Reference Higgins, Thomas, Chandler, Cumpston, Li and Page19 The following criteria were applied: sequence generation; allocation concealment; masking of participants, personnel and outcome assessors; incomplete outcome data drop-out and intention-to-treat analysis; selective outcome reporting; and other threats to validity, including similarity of the groups at baseline, co-interventions, adherence and similar timing of outcome assessment. Studies were rated as ‘low risk’, ‘high risk’ or ‘unclear risk’. Studies were scored with a total ‘low risk’ rating and qualified as at overall low risk of bias (an indication of high quality) if six or more risk of bias variables were assessed as low risk. In other cases, the study was scored ‘high risk’.

Meta-analysis

Comprehensive Meta-Analysis version 3.0 (Biostat.org) for WindowsReference Borenstein, Hedges, Higgins and Rothstein20 was used to analyse the data extracted from included studies and calculate pooled effect sizes, forest plots, heterogeneity and funnel plots. For recurrence of depression, 2 × 2 tables (events and non-events for intervention and control) were converted into risk ratios (RR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI). HR outcome data were calculated separately, as HRs measure time to relapse, and RR and HR outcomes are non-comparable in meta-analysis. Between-study heterogeneity was expected to be high; thus, a random-effects model was applied using the DerSimonian & Laird method used to estimate the between-study variance τ 2.Reference DerSimonian and Laird21 A mixed-effects model was used to perform subgroup analysis on categorical variables for differences between groups. Subgroup analysis included the different treatment combinations of psychological interventions with or without (including tapering) antidepressants and comparisons between different psychological intervention types. Meta-regression analysis was conducted on follow-up duration to assess whether the time point of follow-up affected the results of the meta-analysis.

Multiple study arms

Two studies included psychological intervention both without and with antidepressants versus antidepressant control.Reference Bockting, Klein, Elgersma, van Rijsbergen, Slofstra and Ormel7,Reference Frank, Kupfer, Perel, Cornes, Jarrett and Mallinger22 To avoid double counting,Reference Higgins, Thomas, Chandler, Cumpston, Li and Page19 we halved the control group relapse rates and sample size for these comparisons only in the subgroup analysis comparing psychological interventions with or without antidepressants versus control.

Number needed to treat

The number needed to treat (NNT) was calculated from the inverse of the risk difference to indicate the numbers needed to treat with the relapse prevention intervention to prevent one relapse.

Heterogeneity

Heterogeneity was assessed using I 2, with 0–24% indicating no significant heterogeneity, 25–49% low heterogeneity, 50–74% moderate heterogeneity and 75–100% high heterogeneity.Reference Higgins, Thompson, Deeks and Altman24 The 95% confidence intervalsReference Ioannidis, Patsopoulos and Evangelou25 of I 2 were calculated using the formula from Stata's HETEROGI module.Reference Orsini, Bottai, Higgins and Buchan26

Risk of bias and publication bias

Risk of bias was investigated by a subgroup analysis of the overall risk of bias score for each of the main comparisons, i.e. a psychological intervention with antidepressants versus a psychological intervention without antidepressants (including tapering). Publication bias or small sample bias was assessed by visual inspection of the funnel plot. Egger's test of the interceptReference Egger, Smith, Schneider and Minder27 was applied to test for asymmetry of the funnel plot, which would imply that bias may be present. Duval & Tweedie'sReference Duval, Tweedie, Taylor and Tweedie28 trim and fill procedure was applied to assess whether imputation of studies to address potential publication bias would change the effect size of the meta-analysis.

Results

Characteristics of included studies

After removing duplicates, 14 663 records were screened. Out of 225 full-text articles, 11 studies with 1559 participants (n = 832 intervention group and n = 727 control group) met the inclusion criteria (Fig. 1). The studies were conducted in the USA (n = 4), the UK (n = 3), The Netherlands (n = 2), Canada (n = 1) and Germany (n = 1). The follow-up periods in the studies ranged from 28 to 235 weeks, with an average of 97 weeks. Two tables summarising study and participant characteristics of included studies can be found in the supplementary Appendix. Most of the included patients were at high risk of relapse; 54% of the studies included participants with at least three previous episodes of depression; 27% of the studies included participants with at least two previous episodes; and only two studies (18%) included participants who had experienced at least one previous episode. Most studies (63%) were judged to have a low risk of bias (supplementary Appendix).

Fig. 1 PRISMA study selection process.

In two studies,Reference Bockting, Klein, Elgersma, van Rijsbergen, Slofstra and Ormel7,Reference Frank, Kupfer, Perel, Cornes, Jarrett and Mallinger22 two relapse prevention intervention groups were compared with antidepressants alone. Therefore, 13 comparisons in total were possible for the analyses. Four of these comparisons studied CBT or MBCT, two studied interpersonal psychotherapy (IPT) or preventive cognitive therapy (PCT) and one studied continuation cognitive therapy (C-CT) versus control. A description of the psychological interventions studied is given in the supplementary Appendix. In five of the comparisons, antidepressants were tapered in the psychological intervention group, and in one comparison, antidepressants were not taken or tapered. In the remaining comparisons, continuation antidepressant medication was delivered in combination with a psychological intervention.

Treatment strategies to prevent relapse

Psychological interventions without antidepressants (including tapering of antidepressants) versus antidepressants alone

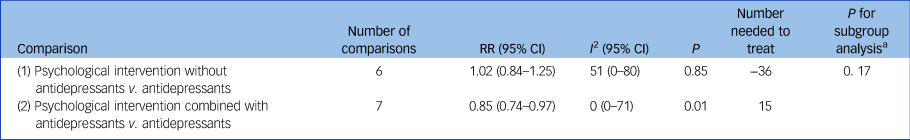

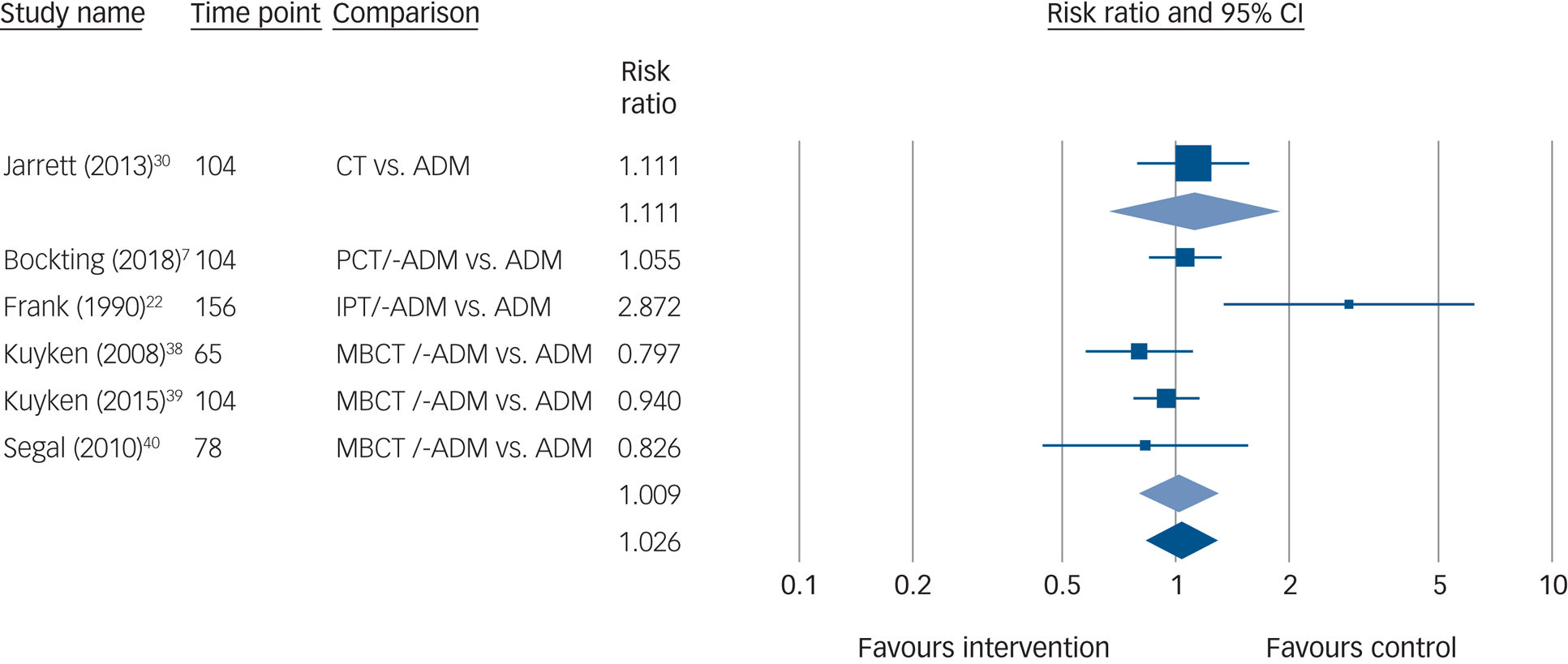

Six studies (n = 948) compared psychological interventions without antidepressants versus antidepressants alone (RR = 1.02; 95% CI 0.4–1.25; P = 0.85 (Table 1 and Fig. 2)). This implies that there was no significant difference in effect between psychological interventions without antidepressants and antidepressants alone. Heterogeneity was moderate: I 2 = 51 (95% CI 0–80). One comparison evaluating the psychological intervention IPT versus antidepressants alone could be considered an outlier because of the high RR found (RR = 2.87; 95% CI 1.33–6.21).Reference Frank, Kupfer, Perel, Cornes, Jarrett and Mallinger22 After removing IPT, the overall effect on five comparisons changed to RR = 0.97 (95% CI 0.85–1.10; P = 0.61) and heterogeneity lowered to I 2 = 0 (95% CI 0–79). Although the effect size changed, the conclusion from the main effect analysis did not change. The overall risk of bias was low in five out of the six comparisons, and the effect size did not vary significantly by the risk of bias score.

Table 1 Risk ratios (RR) for the effects of psychological interventions with or without antidepressant medication versus antidepressants alone

v., versus; n.a., not applicable.

a. P-value for subgroup analysis on risk ratios comparing psychological interventions with and without antidepressants versus antidepressants alone.

Fig. 2 Forest plot of the effects of psychological interventions alone or with tapering versus antidepressants alone on risk ratios.

CT, cognitive therapy; ADM, antidepressant medication; PCT/-ADM, preventive cognitive therapy with tapering of antidepressant medication; IPT/-ADM, interpersonal therapy with tapering of antidepressant medication; MBCT/-ADM, mindfulness-based cognitive therapy with tapering of antidepressant medication.

Five of the six studies (n = 840) compared antidepressant tapering when receiving a psychological intervention with antidepressants alone. A main-effect meta-analysis on these studies found no significant difference between either approach (RR = 1.01; 95% CI 0.79–1.29; P = 0.94; NNT = −37). Heterogeneity was moderate (I 2 = 59; 95% CI 1–83) and the risk of bias was low in all comparisons. One study compared a psychological intervention without antidepressants versus antidepressants alone. We did not further compare the effects of psychological interventions with tapering or psychological interventions alone owing to the small sample size.

Psychological interventions with antidepressants versus antidepressants alone

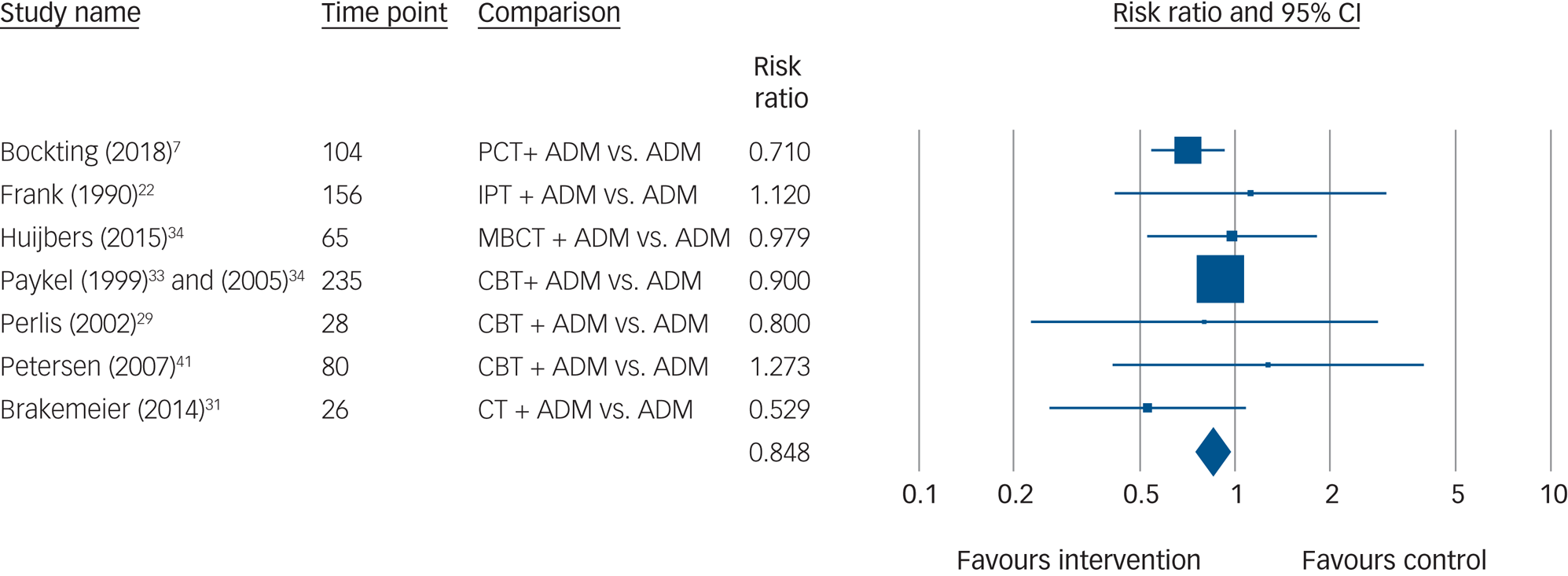

Overall, seven studies (n = 611) compared a psychological intervention with antidepressants versus antidepressants alone. There was a significant difference (RR = 0.85; 95% CI 0.74–0.97; P = 0.01), with combination therapy (psychological intervention plus antidepressants) resulting in a 15% lower relative risk of relapse compared with antidepressants alone (Table 1 and Fig. 3). The NNT was 15 and heterogeneity was not significant (I 2 = 0; 95% CI 0–71). The overall quality of evidence was mixed, with four comparisons showing a high risk of bias and three a low risk. Subgroup analysis showed no different effect size in relation to the risk of bias score at P < 0.10.

Fig. 3 Forest plot of the effects of psychological interventions with antidepressants versus antidepressants alone on risk ratios.

PCT + ADM, preventive cognitive therapy with antidepressant medication; ADM, antidepressant medication; PCT + ADM, preventive cognitive therapy with antidepressant medication; MBCT + ADM, mindfulness-based cognitive therapy with antidepressant medication; CBT + ADM, cognitive–behavioural therapy with antidepressant medication; CT + ADM, cognitive therapy with antidepressant medication.

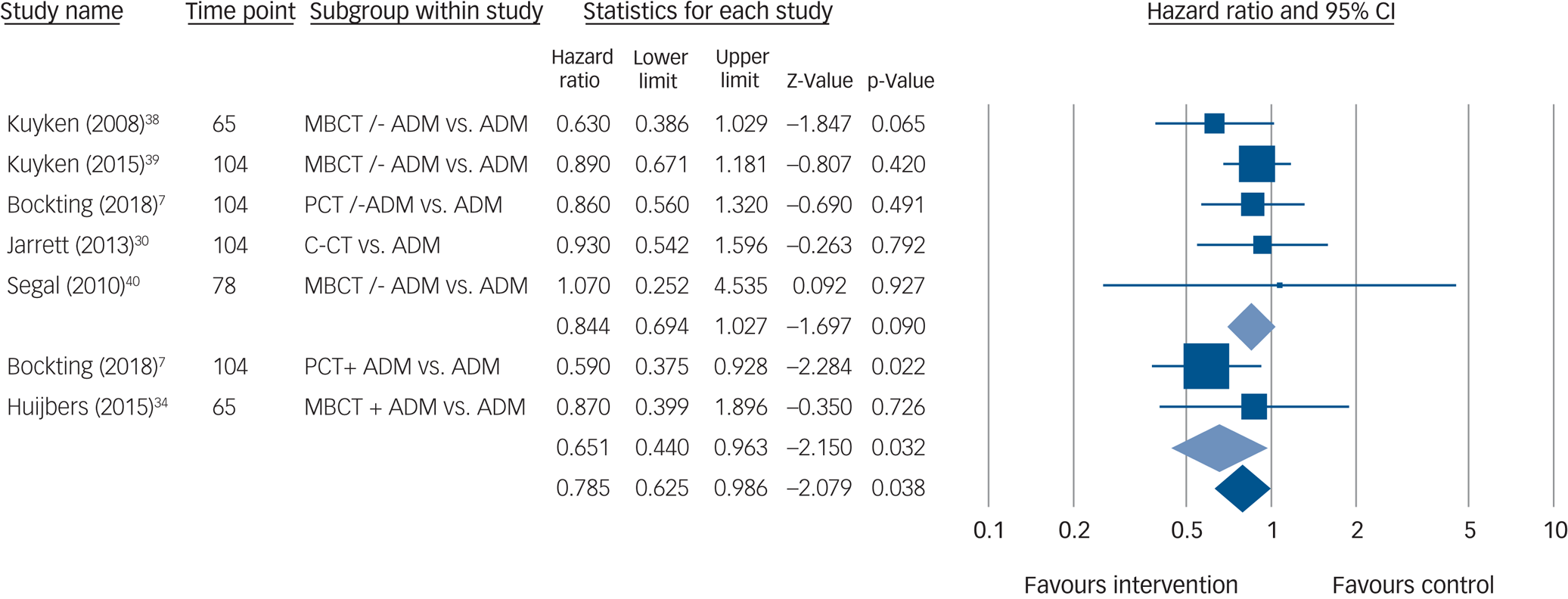

Hazard ratio results

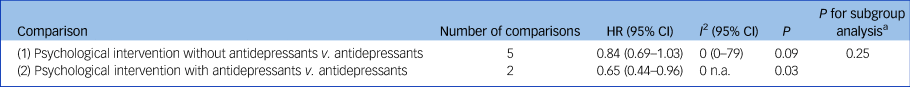

Six of the 11 included studies (seven comparisons) provided data on HR (Table 2 and Fig. 4). The results were in line with findings from the RR analysis in our previous paragraphs, although a smaller number of studies was available. Four comparisons were available where psychological interventions without antidepressants (including antidepressant tapering) were compared with antidepressant medication (HR = 0.84; 95% CI 0.69–1.03; P = 0.09; I 2 = 0; 95% CI 0–79). Two comparisons were available where antidepressants were combined with a psychological intervention and compared with antidepressants alone (HR = 0.65; 95% CI 0.44–0.96; P = 0.03; I 2 = 0). Only one study had a high risk of bias; no further subgroup analyses were conducted owing to the small number of studies available.

Table 2 Hazard ratios (HR) for the effects of psychological interventions with or without antidepressant medication versus antidepressants alone

v., versus; n.a., not applicable.

a. P-value for subgroup analysis on hazard ratios comparing psychological interventions with and without antidepressants versus antidepressants alone.

Fig. 4 Forest plot of meta-analysis comparing psychological interventions with and without antidepressants versus antidepressants alone on hazard ratios.

MBCT/-ADM, mindfulness-based cognitive therapy with tapering of antidepressant medication; ADM, antidepressant medication; PCT/-ADM, preventive cognitive therapy with tapering of antidepressant medication; C-CT, continuation cognitive therapy; PCT + ADM, preventive cognitive therapy with antidepressant medication; MBCT + ADM, mindfulness-based cognitive therapy with antidepressant medication.

Psychological interventions with or without antidepressants versus antidepressants alone

Subgroup analysis conducted between psychological interventions with and without antidepressants did not identify a significant difference between either approach for RRs (Table 1) and HRs (Table 2). We did not conduct subgroup analyses on the different psychological intervention types owing to the small numbers available for some comparisons.

Sensitivity analyses

To study whether previous treatment exposure (i.e. electroconvulsive therapy, psychotherapy) and study design (sequential or maintenance) affected outcomes, we conducted a sensitivity analysis to compare results with and without studies with a maintenance or continuation design.Reference Frank, Kupfer, Perel, Cornes, Jarrett and Mallinger22,Reference Perlis, Nierenberg, Alpert, Pava, Matthews and Buchin29–Reference Paykel, Scott, Teasdale, Johnson, Garland and Moore33 No difference in results was found. Moreover, for both HR and RR analyses, meta-regression analyses were conducted to assess whether the risk of relapse could be predicted on the basis of time to follow-up. In both analyses, as fewer than ten studies were available the results are highly preliminary. For RRs, a covarying trend towards significance for time to follow-up was found in the psychological interventions without antidepressants versus antidepressants alone comparison ((Q(1,5) = 10.24, P = 0.07)). The effect was small; over time the risk of relapse increased, with 0.01 more for patients who received a psychological intervention (with or without antidepressants) compared with those who did not for each additional week of follow-up. For HRs, no covarying effect of time of follow-up on outcome was found.

Publication bias

Although the funnel plot suggested some asymmetry, Egger's test and Duval & Tweedie's trim and fill indicated no potential publication bias in studies comparing psychological interventions without antidepressants versus those with antidepressants (studies trimmed: 0). Potential publication bias was found in comparisons combining a psychological intervention with antidepressants versus antidepressants alone (studies trimmed: 1), yet the change in the adjusted RR was minimal (adjusted RR = 0.84; 95% CI 0.74–0.96). For HR comparing psychological interventions without antidepressants versus antidepressants alone, there was some indication of publication bias, and 1 study was trimmed. Owing to the limited number of studies (n = 2), it was not possible to analyse publication bias for the comparison of psychological intervention with antidepressants versus antidepressant medication alone. All trimmed studies were on the left side of the mean, suggesting that non-significant study results favouring the control group were not published.

Risk of bias

Overall, the risk of bias in the 11 studies was low, with 7 studies having low risk and 4 studies scoring high risk. All individual ratings and overall ratings on the risk of bias domains can be found in Tables 3 and 4 in the supplementary Appendix. It is noteworthy that more recent trials (published since 2010) had low risk as they incorporated procedures that decreased the risk, including pre-registering the trial protocol. For all studies, risk of masking bias for both participants and personnel was scored as ‘high’; this is due to the nature of this type of research, where masking is often not possible. Other studies had problems pertinent to the trial: the trial of Huijbers et al (2015)Reference Huijbers, Spinhoven, Spijker, Ruhe, van Schaik and van Oppen34 had no allocation concealment; the trial of Jarrett et al (2013)Reference Jarrett, Minhajuddin, Gershenfeld, Friedman and Thase30 had differences in length of follow-up and number of sessions attended; and Petersen et al (2007)Reference Petersen, Pava, Buchin, Matthews, Papakostas and Nierenberg41 was in part funded by a pharmaceutical company.

Discussion

This is, to the best of our knowledge, the first systematic review to assess whether psychological interventions can be delivered as an alternative to antidepressants, or whether a combination of psychological intervention and antidepressants may be more effective than medication alone. Two key findings can be reported. First, we found no evidence for an increased risk of relapse in the groups where a psychological intervention was delivered when participants were tapering antidepressants versus where participants continued taking antidepressants. Second, adding a psychological intervention to antidepressants after remission significantly reduced the risk of relapse compared with taking antidepressants alone.

Although previous meta-analyses found that patients have a decreased risk of relapse when they receive psychological intervention without antidepressants compared with clinical management or maintenance antidepressant medication,Reference Guidi, Tomba and Fava11,Reference Biesheuvel-Leliefeld, Kok, Bockting, Cuijpers, Hollon and van Marwijk12 we found no significant difference between either condition. A potential explanation might be different inclusion and exclusion criteria, as we only included studies where outcomes were assessed using diagnostic interview by an independent assessor and we also included more recent publications.Reference Bockting, Klein, Elgersma, van Rijsbergen, Slofstra and Ormel7,Reference Huijbers, Spinhoven, Spijker, Ruhe, van Schaik and van Oppen34 In line with previous literature, we found that the combination of psychological intervention with antidepressants significantly reduces the risk of relapse compared with antidepressants alone.Reference Guidi, Tomba and Fava11,Reference Biesheuvel-Leliefeld, Kok, Bockting, Cuijpers, Hollon and van Marwijk12

Implications for clinical practice

These findings are highly relevant to current clinical practice as they differ from current clinical guidelines for depression. For patients with two or more previous depressive episodes, clinical guidelines currently recommend long-term antidepressant use after remission4,5 and no routine offering of psychological intervention (PCT or MBCT) for patients who are tapering off their antidepressant use. We found no evidence to suggest that there is a difference between patients receiving a psychological intervention while tapering off antidepressants versus antidepressant continuation alone. Thus, the combination of tapering and psychological interventions might be a viable alternative to long-term antidepressant use for patients with multiple previous episodes who wish to taper. On the other hand, should patients deem continuation of antidepressants acceptable, adding a psychological intervention significantly reduces the risk of relapse compared with antidepressants alone.

Given that our results suggest that short-term preventive psychological interventions, in particular MBCT or PCT, might be an alternative to long-term antidepressants, we wish to add a note of caution. In general, tapering of antidepressants requires an individualised approach, and symptoms need to be monitored closely.Reference Horowitz and Taylor9 Novel ways of tapering, i.e. over a longer time and with more gradual reduction, may help mitigate withdrawal effects but requires further RCT studies.Reference Horowitz and Taylor9 Besides, before suggesting or recommending psychological interventions, the availability of evidence-based psychological interventions for relapse prevention (i.e. CBT, MBCT, PCT) should be considered, as they may not be available or routinely implemented.Reference Crane and Kuyken35

Strengths and limitations

This review has several strengths. It is the first review assessing this comparison specifically among high-quality RCTs, including studies from a range of settings where most patients had two or more previous episodes, improving the translatability of these results to a high-risk population who are currently mostly offered antidepressant maintenance.

This review also has some limitations. In terms of generalisability, included studies were only from high-income countries, meaning that there is still more research needed in the translation of these results to low- and middle-income countries. In our meta-analyses, we did not include adverse outcomes due to tapering or the approach taken to tapering (i.e. duration, dose) nor were these commonly reported; we recommend that future studies monitor these and describe the tapering procedure in detail, so as to inform tapering practices when delivering a preventive psychological intervention.

Multiple studies had various follow-up points; we selected the longest time of follow-up for each study and assumed proportional hazards, and then we conducted a sensitivity analysis to assess whether the time to follow-up might be associated with the risk of relapse found.Reference Higgins, Thomas, Chandler, Cumpston, Li and Page19 Although this approach may increase inconsistency across studies and heterogeneity,Reference Higgins, Thomas, Chandler, Cumpston, Li and Page19 we did not have further data available to study this in more depth by, for example, testing RR or HR at different follow-up points.

Finally, the number of studies in total is still small, which limits the subgroup analyses we were able to conduct and power to detect a significance between subgroups.

Overall, uncertainties remain that require further research. In particular, it is important to note previous treatment combinations during the acute phase and what effect these might have had on outcomes in remission. For instance, a recent trial by deRubeis and colleaguesReference DeRubeis, Zajecka, Shelton, Amsterdam, Fawcett and Xu36 showed that the combination of antidepressant medication and CBT may interfere with any prophylactic effect CBT may have during the relapse prevention stage. Also, Barlow et al (2000)Reference Barlow, Gorman, Shear and Woods37 studied CBT combined with antidepressants or alone in the treatment of panic disorder and observed that combination therapy resulted in little benefit over monotherapy (antidepressants or CBT). Although these findings are to be confirmed further, it is also important to note that they do not hold for starting psychotherapy after remission to prevent relapse and recurrence. This meta-analysis suggests that adding a brief psychological intervention to antidepressant continuation is more effective at reducing the risk of depressive relapse compared to continuing antidepressants alone, suggesting greater focus should be placed on this approach.

Further research could also assess which specific intervention types might be more effective (MBCT, PCT, IPT) than others, depending on patient profiles. Finally, it would be of interest whether there are particular patient profiles associated with a more or less favourable response to tapering or a combination of a psychological intervention with antidepressant medication. More research in the form of individual participant data and network meta-analysis could assess what works for whom and allow for even more targeted recommendations.

In terms of future research, it would also be beneficial to assess how these results can be best translated into clinical practice and clinical guidelines. Current guidelines for depression in the UK and the USA do not recommend a psychological intervention being delivered while tapering but recommend it as an add-on for patients at high risk of relapse.4,5 Our results suggest that the addition of a psychological intervention when tapering would improve patient outcomes, and it would generally improve outcomes for patients who are on long-term antidepressant medication. Developing our findings into recommendations in clinical guidelines, with substantial input from patients, families and clinicians, would be a recommended next step.

In this meta-analysis, we found no evidence to suggest that psychological interventions added to tapering antidepressants increase the risk of relapse versus antidepressants alone for patients with multiple previous episodes of depression. Adding a psychological intervention to maintenance antidepressants significantly reduces the risk of relapse, making this an option that one should consider adding routinely in clinical practice where possible. Healthcare providers and clinical guideline developers can explore how psychological interventions can be routinely recommended and implemented alongside (the tapering of) antidepressants to improve patient choice and reduce the risk of depressive relapse.

Supplementary material

Supplementary material is available online at https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.2020.198.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author on request.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Alicia Segovia, MSc, and Emma Boers, BSc, for support with title and abstract screening, and Catherine Moore, MSc, for conducting the second-rater extractions on the included studies.

Funding

The authors thank the Amsterdam Public Health research institute for providing a small grant which has funded software and travel costs.

Author contributions

J.J.F.B. co-formulated the research question, co-designed the study, led on extractions, data analysis and drafting the article prior to submission. M.E.B. co-formulated the research question, co-designed the study, co-conducted study selections and extractions, provided analysis advice and critically reviewed the article prior to submission. M.H. supported with the design and extractions, analysis of the manuscript and preparing the risk of bias tables and critically reviewed the article prior to submission. M.S. supported with the design, and analysis of the study as well as critically reviewed the article prior to submission. D.D.E. supported with the design of the study and critically reviewed the article prior to submission. P.C. supported with the design and analysis of the study and critically reviewed the article prior to submission. C.L.H.B. co-formulated the research question, co-designed the study and extractions, supported with analysis advice and critically reviewed the article prior to submission.

Declaration of interest

C.L.H.B. is co-developer of the Dutch multidisciplinary clinical guideline for anxiety and depression, for which she receives no remuneration; is a member of the scientific advisory board of the National Health Care Institute, the Netherlands, for which she receives an honorarium, although this role has no direct relation to this study; and has developed a preventive cognitive therapy based on the cognitive model of A.T. Beck.

ICMJE forms are in the supplementary material, available online at https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.2020.198.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.