10.1

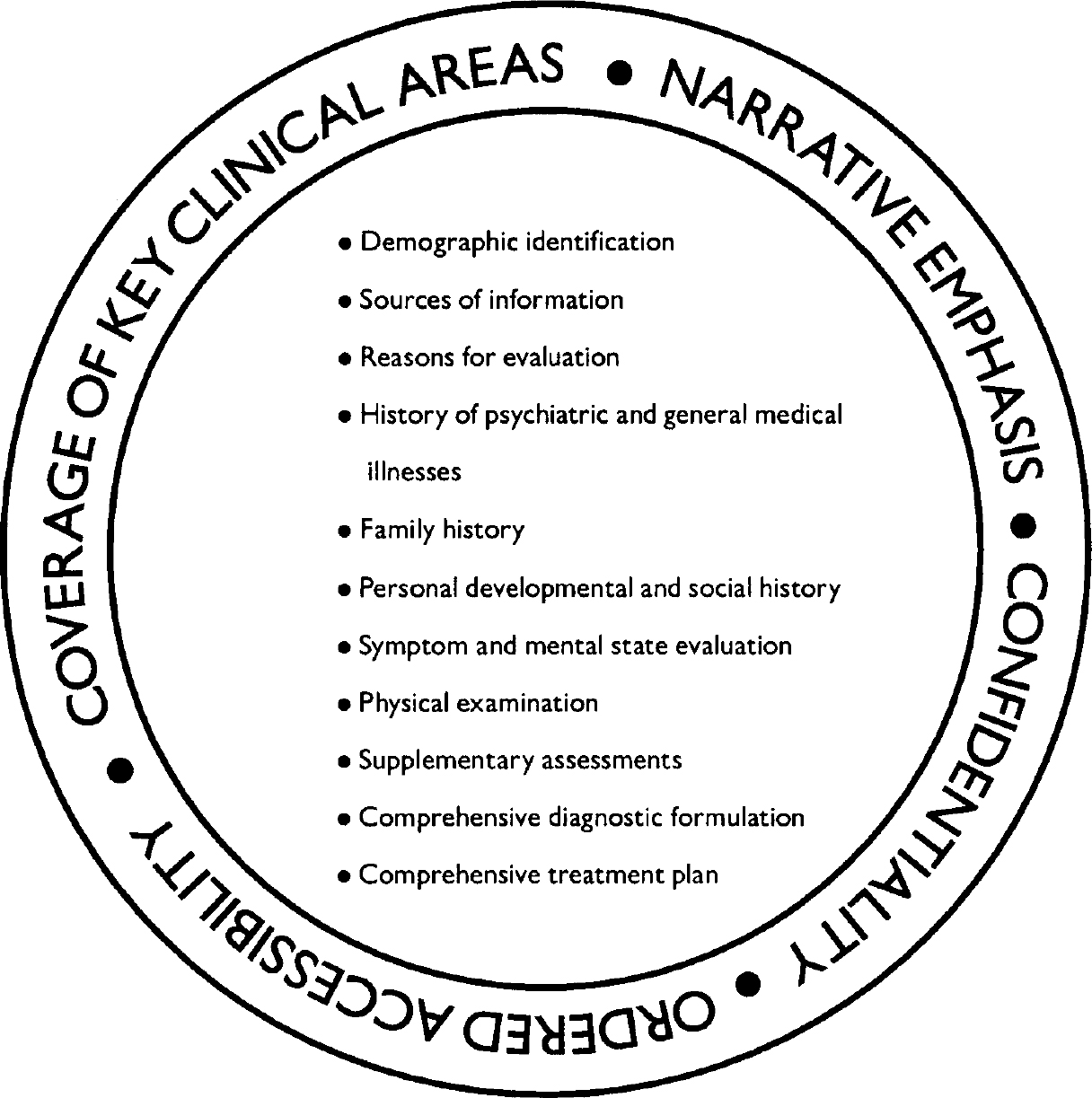

A systematic record of information collected during the process of diagnosis and care is essential to document understanding of the patient's mental, physical and social condition and the clinical service provided (Fig. 10.1).

Fig. 10.1 Organising a clinical chart.

10.2

Clinical charts are basic informational tools for all members of the clinical team. Charts should be kept in a secure and confidential location and should be accessible through an orderly process to authorised clinical personnel. In some settings, clinical charts may be electronically available.

10.3

A chart should include narrative statements (using the patient's own words whenever possible) in all sections of the assessment and care process. An effort should be made to ensure legibility of these statements. Occasionally, a chart may include, in its relevant sections, structured or semi-structured components to ensure that important information is covered in an effective way.

10.4

The clinical chart should begin with a record of basic identifying information, including the patient's name, address, telephone number, date of birth, gender, ethnicity, religion, education, marital status, employment status, insurance coverage (if relevant) and next of kin.

10.5

The results of a clinical diagnostic assessment and its linkage to care should be recorded in narrative form under standard headings, such as the following:

-

(a) sources of information

-

(b) chief complaint or reason for evaluation

-

(c) history of present illness

-

(d) past psychiatric and general medical history

-

(e) family history

-

(f) personal, developmental and social history

-

(g) symptom and mental state evaluation

-

(h) physical examination

-

(i) supplementary assessments

-

(j) comprehensive diagnostic formulation

-

(k) comprehensive treatment plan.

10.6

The history of psychiatric and general medical illness should be recorded, as far as possible in chronological sequence, noting significant events, ages and dates.

10.7

A family history of mental and general medical disorders and treatment should be collected for all known first- and second-degree relatives, including children, on both sides of the family. Personal, developmental and social history should be recorded chronologically. In addition to narrative statements, key milestones and critical events may be recorded in a structural manner.

10.8

The record of the symptom and mental state examination should cover all important areas of mental activity and behaviour (e.g. appearance, overt behaviour, mood and affect, speech and thought process, thought content, perception, sensorium or alertness, memory, judgement and insight). In every case, personalised descriptions should be presented. Checklists may also be used. Whenever possible, a physical examination should be conducted.

10.9

A comprehensive diagnostic formulation that incorporates the information obtained through the standardised and idiographic diagnostic processes should be recorded. The use of a systematic format, as outlined in earlier parts, is advisable.

10.10

The clinical chart should include a treatment plan, based on the comprehensive diagnostic formulation. It is advisable to use a systematic treatment plan format linking clinical problems with specific interventions, such as that presented elsewhere in this supplement (IGDA Workgroup, WPA, 2003: this suppl.).

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.