Abstract

In this autobiographical essay I reflect on my training in linguistics and the way it affected my interpretation and development of SFL theory. In particular I am concerned to show how I tried to help SFL evolve, accumulating previous understandings into a model with additional theoretical architecture taking descriptive responsibility for a wider range of linguistic data. This evolution is illustrated with respect to my work on discourse semantics (as part of stratified content plane), genre (as part of a stratified context plane) and appraisal (a discourse semantic framework for analysing feeling).

Similar content being viewed by others

Orientation

In November 2012 I was invited to Shanghai to attend the launch of my collected papers by Shanghai Jiao Tong University Press. As part of the proceedings, I was asked to give a lecture about the development of my work, and to participate in an interview about the evolution of systemic functional linguistics (hereafter SFL). This paper is based on those presentations, during which I tried to foreground the theme of evolution – with respect to some of the ways in which I have attempted to expand the theoretical and descriptive focus of SFL, moving beyond the clause towards considerations of text and context.

Singulars and regions

In order to frame this discussion I will draw upon the recent ongoing dialogue between SFL and the social realist theory articulated by Bernstein (e.g. 1999, 1996/2000) and neo-Bernsteinian scholars (e.g. Muller 2000, 2007; Maton 2007, 2014, Maton & Muller 2007) – with respect to the SFL register variable field and social realist perspectives on knowledge; for access to this conversation see Christie & Martin (2007), Christie & Maton (2011) and Maton et al. (in press). To begin we need to distinguish between singulars and regions, which Bernstein (1996: 23) outlines as follows:

A discourse as a singular is a discourse which has appropriated a space to give itself a unique name… for example physics, chemistry, sociology, psychology… these singulars produced a discourse which was about only themselves.... had very few external references other than in terms of themselves… created the field of the production of knowledge…

…in the twentieth century, particularly in the last five decades… the very strong classification of singulars has undergone a change, and what we have now.... is a regionalisation of knowledge… a recontextualising of singulars… for example, in medicine, architecture, engineering, information science… any regionalisation of knowledge implies a recontextualising principle: which singulars are to be selected, what knowledge within the singular is to be introduced and related… regions are the interface between the field of the production of knowledge and any field of practice…

In this paper I’ll focus on the singular linguistics – on one of its functional theories, SFL, in particular (as opposed to the region education, where I have tried to contribute to the development of literacy programs).

Disciplinarity

Throughout his career Bernstein was concerned with the difference between common and uncommon sense, and the role education plays in polarising the distribution of uncommon sense knowledge to learners. His culminative publications reworked this complementarity in terms of horizontal vs vertical discourse (Bernstein 1996/2000: 157):

A Horizontal discourse entails a set of strategies which are local, segmentally organised, context specific and dependent, for maximising encounters with persons and habitats… This form has a group of well-known features: it is likely to be oral, local, context dependent and specific, tacit, multi-layered and contradictory across but not within contexts.

… a Vertical discourse takes the form of a coherent, explicit and systematically principled structure, hierarchically organised as in the sciences, or it takes the form of a series of specialised languages with specialised modes of interrogation and specialised criteria for the production and circulation of texts as in the social sciences and humanities.

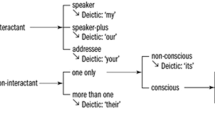

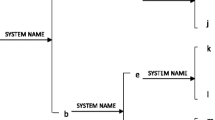

And within vertical discourse he set up a complementarity of hierarchical vs horizontal knowledge structure. A hierarchical knowledge structure was characterised as “a coherent, explicit and systematically principled structure, hierarchically organised” which “attempts to create very general propositions and theories, which integrate knowledge at lower levels, and in this way shows underlying uniformities across an expanding range of apparently different phenomena” (1999a: 161, 162). A horizontal knowledge structure was defined as “a series of specialised languages with specialised modes of interrogation and criteria for the construction and circulation of texts” (1999a: 162) -- such as the disciplines of the humanities and social sciences (e.g. for functional linguistics, the ‘languages’ of systemic functional linguistics, lexical functional grammar, role and reference grammar, functional grammar, functional discourse grammar, cognitive linguistics etc.). Bernstein used the image of a triangle to represent the nature of knowledge in hierarchical knowledge structures, with general axioms at the top of the triangle integrating lower level understandings; and for horizontal knowledge structures he used a series of L’s, representing the proliferation of theoretical perspectives involved (Figure 1).

Wignell, presenting at the ‘Reclaiming Knowledge’ workshop at the University of Sydney in December 2004 (cf. Christie & Martin 2007, Wignell 2007), commented that the social sciences might be better characterised as a series of warring triangles – since they tend to model themselves on physical and biological sciences and are more successful at winning institutional rather than epistemological ascendency; this contrasts with the humanities where technicality and the drive to integration via general models and propositions is less strong (or perhaps even anathema). The broader profile this implies is outlined in Figure 2 below, which uses the size of triangles and L’s to indicate the sense in which one or another triangle achieves hegemony in the social sciences, or becomes more fashionable in the humanities.

The tendency of horizontal knowledge structures to ‘progress’ via the introduction of a new specialised ‘language’ draws attention to the centrifugal potential of such disciplines. For a ‘language’ like SFL this raises questions about the fault lines around which new ‘dialects’, ‘registers’ or even ‘languages’ might evolve. Martin (2011) explores one aspect of this potential, focusing on axis and stratification issues; towards the end of this paper, and also in Martin (2013a), several additional fault lines are noted. Here however I want to ask how a singular like SFL might evolve, subsuming its past into possible futures. How in other words has it expanded theoretically, thereby affording a recontextualisation of previous descriptions in relation to an expanding set of linguistic phenomena (as crudely imaged in Figure 3)?

In doing so I’ll reflect on my own work on discourse semantics, context and appraisal – as instances of knowledge building. But to contextualise this work I’ll first of all have to introduce some personal and intellectual history.

My training

During my final year of secondary education, like many young Canadians I was caught up in ‘Trudeau-mania’, enamoured of the sporty intellectual dandy, Pierre Elliot Trudeau, who was about to be elected Prime Minister. This inspired me towards a career in politics and/or foreign affairs. So it was that in 1968 that I enrolled in Glendon College, a small liberal arts college on a separate campus from the rest of York University in Toronto. Glendon was specialising in preparing would-be agents of symbolic control such as myself for public life, and offered a bilingual program for these future mandarins. Accordingly we were all enrolled in first year English and French alongside other humanities and social science subjects (and one unit in ‘natural science’ to round us off). My first year lecturer for English was Michael Gregory, a dramatic imposing figure who had recently founded the English Department at Glendon. Gregory had designed an innovative English program, foregrounding drama, stylistics and linguistics (Cha 1995, de Villiers and Stainton 2001, 2009). Like most linguists I had no idea what linguistics was before entering university, but I was soon hooked. From first year Gregory trained us in his version of scale and category grammar (inspired by Halliday 1961 and now published as Gregory 2009), stylistics (Spencer & Gregory 1964) and register theory (Gregory 1967, Gregory & Carroll 1978). And he hired a student of Gleason’s, Waldemar Gutwinski, to train us in his specialisation, cohesion (Gutwinski 1976) – as well as what was then known as transformational generative grammar and stratificational linguistics. So I was analysing cohesion in texts from 1968, at a time when discourse analysis in linguistics was still in its infancy; and while I loved grammar, analysis of textual relations beyond the sentence became my chief concern.

We learned about Gleason’s work from Gutwinski, and so for my MA I went downtown to the University of Toronto. I furthered my studies in generative grammar and stratificational grammar there; I was particularly fascinated by the training in relational networks offered by Peter Reich – an approach to formalising language as a network of relations without using any linguistic terms at all (Lockwood 1972, Makkai & Lockwood 1973). For our field methods course we worked on Tagalog, which was the beginning of my interest in that language (e.g. Martin 2004). And Peter Reich invited Sherry Rochester to give a lecture on schizophrenic speech in our psycholinguistics course, which led to my work with her in clinical linguistics (Rochester & Martin 1979). With Gleason I had an opportunity to learn about his approach to discourse, which he had developed with the missionary linguists (at Hartford and Toronto) whose PhDs he supervised. I particularly enjoyed his many discussions of what he called the ‘architecture of language’ and ‘strategies of description’. Gleason (1961) had of course written the canonical structuralist textbook, Introduction to Descriptive Linguistics. But he was very well versed in generative grammar, tagmemics, stratification grammar and SFL as well, and was far and away the deepest meta-theoretician I have ever known (though of course regularly dismissed as such by the generative grammar ‘revolutionaries’ who were so intent at the time on policing the 1957 iron curtain Chomsky had forged by way of shutting down the American structuralist heritage he was in fact building upon).

Inspired by Gregory’s teaching, my dream however was to study with Michael Halliday, and I was lucky enough to win a Canada Council scholarship that enabled me to commence PhD work with him at Essex in 1974. I went back to Toronto after a year to work with Gleason and Rochester while Halliday settled in Australia, and then joined him at the University of Sydney in January 1977 to complete my thesis. I got a job in his newly founded department in 1978, and have worked there ever since. My PhD looked at the development of story telling by primary school children, focusing on participant identification and conjunction – and undertaking a statistically based semantic variation analysis of their different coding orientations at ages 6/7, 8/9 and 10/11 (Martin 1983). Alongside courses in phonology, generative grammar and schools of linguistics that no one else wanted to teach, I early on developed a course on functional varieties of language in our MA Applied program, and over time grasped opportunities to teach functional grammar, discourse analysis, register and genre theory and media discourse as well. It was through our MA program that I first made contact with Frances Christie and Joan Rothery, and interacting with them gave rise to my interest in literacy and educational linguistics (Rose & Martin 2012).

This training was of course a highly unusual one for a linguistics student in North America at the time (and continues to be so!) and led to a rather curious reading path that I’ll sketch here. As noted above, from first year university I was trained in Gregory’s approach to grammar, register and stylistics. Gregory was a great admirer of Firth, one of Halliday’s teachers, and spent many seminar hours reading to us from his papers and commenting on them. Recent papers by Halliday, often hot off the press, received the same hermeneutic treatment -- beginning in Gregory’s office and often continuing over drinks in the staff club. Gutwinski inspired my reading in stratificational linguistics, especially Gleason’s students’ theses and Lamb (1966); from Lamb one can’t help but move on to his inspiration, Hjelmslev (1947, 1961), and from there in turn to his inspiration, Saussure (1916/1966). At Essex I had a chance to take a course in functional semantics with Halliday, which oriented us to work by Malinowki and Firth, the Prague School and Labov. Later on in Sydney, my critical theory colleagues introduced me to work published under Bakhtin’s name. Since then it is probably fair to say I have spent most of my concentrated reading time reading and re-reading work by Halliday and by Matthiessen, and trying to better appreciate what they mean.

These autobiographical details may seem out of place in an article in a scholarly linguistics journal. But for readers who have indulged me thus far, I will do my best to show the relevance of this personal history to the ways in which I have tried to contribute to SFL.

Evolving SFL

Discourse semantics

The first piece of evolution I’ll discuss has to do with the model of stratification in SFL. Let’s begin with Hjelmslev’s well-known complementarities of content/expression and form/substance. Following Saussure, Hjelmslev conceived of language as form not substance (1947, 1961). As Saussure analogised, language is like the waves we see at the beach – since waves are neither the amorphous body of water below nor the amorphous air movement above but rather the interaction of one substance with the other (“the waves resemble the union of coupling of thought with phonic substance” (Saussure 1916/1966: 112). As linguists we are semiotic surfers: we study the waves (we study form, not substance, in Hjelmslev’s terms) (Table 1).Hjelmslev further clarifies that language is not a simple system of signs; the bonding of signifié with signifiant is far more complex than that. Rather, language is a stratified system of signs, with both a content plane and an expression plane. The influence of Hjelmslev’s reasoning on Halliday’s early modelling is clear in Figure 4 below – with substance divided into phonic and graphic formlessness, and extra-textual features.

Levels of language (from Halliday 1961 /2002: 39).

As presaged in Figure 4, SFL’s orientation to stratification moves beyond Hjelmslev’s concept of ‘double articulation’ (to use Martinet’s 1949 terms) to incorporate further levels of analysis. The term context in Figure 4 reflects Firth’s approach to meaning as function in context (e.g. Firth 1957a) – positioned there as a third plane (a third stratum in SFL terms). In Halliday’s later work the term semantics is adopted for this level, resulting in a tri-stratal model with a stratified ‘content plane’ (‘triple articulation’ if you will) – regularly imaged with co-tangential circles as in Figure 5 below (e.g. Matthiessen & Halliday 2009: 87).

This evolving conception of language as a tri-stratal system contrasted for me in interesting respects with the stratificational approach developed by Gleason and his students (Cromack 1968, Gleason 1968, Gutwinski 1976, Stennes 1969, Taber 1966). For them the ‘third’ stratum was conceived as discourse, reflecting their concern with bible translation and the need to describe text relations beyond the sentence. Halliday & Hasan’s emphasis on the idea that a text is not just a big sentence but rather ‘a semantic unit: a unit…of meaning…realized by sentences’ (1976: 2, their emphasis) indicates that the two approaches are not as far apart as the terminology might lead one to fear (Figure 6).

Nevertheless, work on semantics in SFL has regularly concerned itself with what might be called clause semantics (e.g. Halliday’s work on speech function, Halliday & Matthiessen’s work on ideational semantics, and Hasan’s semantic networks; e.g. Halliday 1984, Halliday & Matthiessen 1999 and Hasan 2009 respectively). As a discourse analyst I have always wanted to emphasise the need to move beyond the clause when considering text structure, and began by referring to the third stratum as discourse (following Gleason), and later on, by way of compromise, as discourse semantics. Year after year, the number of papers at SFL conferences (and worse, the number of SFL publications) that undertake a grammar analysis of a text and present it without apology as if was a text analysis has confirmed in me the importance of reinforcing the concept of text as a semantic unit through the terminology we use in our modelling.

As far as discourse structure was concerned, Gleason viewed it as different in kind from syntax (for which he was inclined towards a tagmemic slot and filler approach, after Pike – Pike 1982, Pike & Pike 1983). For discourse he proposed the idea of a network in which nodes could have multiple connections with one another (as opposed to a constituency tree where parts can be related to wholes but not to one another); this network he referred to as a reticulum. For a short phase of discourse such as The sharks circled once, the insertion bird lifted up to join them and all four peeled out back toward the sea a reticulum would have been designed that displayed participant tracking relationships (the sharks ←the insertion bird ←ellipsis ←all four), conjunctive relations among events (circled ^ lifted ^ join ^ peeled) and what in SFL are conceived of as transitivity relations among the process, participants and circumstances (e.g. the sharks as Actor, circled as Process, once as Extent in time). The three different types of discourse relation are circled in Figure 7 below, which is modeled on the kind of layout Gleason and his students favored for reticula.

The crucial point here is that for Gleason texts were conceived as having a different kind of structure than clauses, but as having structure – discourse structure. This conception contrasts with Halliday the grammarian’s treatment of cohesion as non-structural relations (Halliday & Hasan 1976: 29) complementing the structural realisations of the textual metafunction (1973: 141). This ‘grammar and glue’ perspective on cohesion is outlined in Figure 8 below, Halliday’s 1973 rank by metafunction profile of English grammar.

Halliday’s ( 1973 : 141) function/rank matrix for the grammar of English.

So a central concern for me was reinterpreting cohesive ties as discourse semantic structures and the systems behind them as discourse semantic systems – a project precipitated by Hasan’s work on componential and organic cohesion, cohesive harmony and text structure (e.g. Chapters 4, 5 and 6 of Halliday & Hasan 1980). English Text (Martin 1992a) consolidates this work, recontextualising cohesion as discourse semantic systems and structures as outlined below; for seminal papers see Martin (2010a, 2010b). Martin & Rose (2003/2007) provide an accessible introduction to this recontextualisation.

Later on appraisal emerged as a discourse semantic system not originally included as a dimension of cohesion analysis (Martin & White 2005), further discussed in 5.3 below.This conception of discourse semantics made it possible to analyse the organisation of discourse not simply as a list of cohesive ties relating one lexicogramamatical unit to another, but as a further level of structure in its own right. Figure 9 below exemplifies this approach, for conjunctive relations. The reticulum displays the internal and external conjunctive relations that obtain, including their explicitness, their type and their scope.

Recontextualising cohesion as discourse semantics also allows us to reconsider its treatment by Halliday as part of the textual metafunction. As outlined in Figure 10, negotiation and appraisal can now be interpreted as interpersonal resources, ideation and conjunction as ideational and identification and periodicity as textual.

And this re-allocation of discursive resources to metafunctions allows us to make predictions about the kind of structure through which they will tend to be realised (following on from Halliday 1979) – prosodic structure for interpersonal systems, particulate structure for ideational ones (including orbital and serial structures) and periodic structure for textual ones. This radically reconceptualises Halliday & Hasan’s (1976) notion of a ‘cohesive tie’ and what might count as an analysis of cohesion in text (cf. the sample text analyses in Halliday & Hasan 1976: 340–355).

This re-allocation also has serious implications for the study of register, especially for those interested in exploring Halliday’s proposals for mapping intrinsic functionality (metafunctions) onto context (tenor, field and mode) – in the proportions interpersonal is to tenor, as ideational is to field, as textual is to mode (e.g. Halliday 1969, 1973). Based on Halliday’s function/rank matrix in Figure 8 above, we might predict that cohesion will be strongly associated with composing mode. Alternatively, from the perspective of Figure 10, different aspects of cohesion would correlate with different dimensions of register – with tenor by and large enacted through negotiation (and appraisal), field by and large construed through conjunction and ideation and mode by and large composed through identification and periodicity. There are clear implications in this for how we model context, the second piece of SFL evolution to which I now turn.

Genre

At this point it is useful to return to Hjelmslev (1961), and another of his famous complementarities – this time between denotative and connotative semiotic systems. A denotative semiotic is defined as one with its own expression plane (e.g. language, image, dance); a connotative semiotic on the other hand deploys another semiotic system as its expression plane (for which Hjelmslev gives the example of style). Recasting in SFL terms, what we are looking at here can be interpreted as a particular conception of context in relation to language, as outlined in Figure 11.

The relation between language and context is more naturally imaged in SFL terms as Figure 12 below, with context privileged as a higher stratum of meaning (cf. Halliday 2002/2005b for a clear articulation of this position). The influence of Firth (e.g. 1957a/1968: 173–177) is at play here, with context included as a crucial part of the spectrum of analyses needed to account for meaning (as function in context) – as also reflected in the context label for the third ‘plane’ in Halliday’s early model in Figure 4 above.

At this point, to clarify the discussion, it may be useful to distinguish between two perspectives on the relation between language and social context, which we can refer to as supervenient and circumvenient. The supervenient perspective was the one just introduced, whereby context is treated as a higher stratum of meaning; the circumvenient one would alternatively see language as embedded in social context, where social context is interpreted as extra-linguistic. As Figures 4 and 12 indicate, the latter is not the way Halliday proposes treating context in SFL. The distinction is imaged in Figure 13, using co-tangential circles for the supervenient relation, and concentric circles for the circumvenienta one.As noted above Halliday suggests modelling context metafunctionally, as tenor, field and mode (as outlined in Figure 14 below).

My teacher Gregory however (who developed his model of context at a time when Halliday’s conception of intrinsic functionality was just emerging in SFL) proposed four variables not three. So I was initially trained to analyse register variation with respect to field, mode, personal tenor and functional tenor; Ellis and Ure (Ellis & Ure 1969, Ure and Ellis 1977) were developing a similar four variable model at about the same time, using the terms field, mode, formality and role. I drew on Gregory’s model in my first iterations of the functional varieties of language course I noted above, with students who were also being trained by Halliday in the same program. As we all know, early on in their studies students tend to find alternative analytical frameworks confusing, rather than intriguing – and our MA students spent a lot of time complaining about the different perspectives. Two students who did in fact find the difference intriguing, Guenter Plum and Joan Rothery, suggested positioning functional tenor as a deeper variable, since the purpose of a text influenced all of interpersonal, ideational and textual meaning. And they further suggested that it was functional tenor that was in fact responsible for what we came to call the schematic structure of texts (we had Labov & Waletzky’s 1967 work on narrative structure, and Hasan’s work on appointment making and service encounters in mind; Hasan 1977, 1979, Halliday & Hasan 1980). Students continued to complain about the problem of having two kinds of tenor, personal and functional, now on different levels of abstraction. After more discussion, we decided to re-name the more abstract level genre (and could thus abbreviate the term personal tenor to tenor). The evolution of this scaffolding for context is outlined in Figure 15 below – in Hjelmslevian terms, with language the expression plane of register and register (tenor, field and mode) now positioned as the expression plane of genre.

Contrary to reports of the emergence of this model from our educational linguistics work in primary school, the research groupb developing studies of register and genre from circa 1980 to 1985 included Plum, who worked on a variety of spoken genres elicited from dog breeders (Plum 1988), Ventola, who studied Finnish migrants’ interactions with Australian staff in post office and travel agency service encounters (Ventola 1987), Eggins, who examined dinner table conversations among her housemates and friends (Eggins & Slade 1997), Rothery, who was interested in doctor/patient consultations as well as primary school writing (Rothery 1996), and myself, a would-be critical linguist, who was working on environmental and administrative discourse (Martin 1985b, 1986a, [b]). This work is consolidated in Martin 1992a; for a comprehensive updated introduction see Martin & Rose 2008. Hyon 1996 is probably the paper most responsible for confusion about the heritage of the genre theory outlined above; her article makes no reference to the work by Plum, Ventola and Eggins, nor Martin 1992a, and as far as anyone can recall, she didn’t in fact interview me when doing fieldwork in Australia in 1994. That said, her article put Australian genre theory on the map as it were, and we cannot help but acknowledge the prestige she bestowed on our enterprise through her 1996 TESOL Quarterly publication. Martin 1984a is in fact the seminal article popularising this work for an education audience (also not referenced by Hyon).

Figure 16 uses the co-tangential circle motif to image the stratified model of context under discussion here. Note that since two levels of context were being proposed, we needed names to distinguish them. Alongside genre for the deeper level of context, we adopted register as the cover term for field, tenor and mode. This seemed to us at the time the term with the best fit in relation to Halliday et al.’s (1964) and Gregory & Carroll’s (1978) usage – although as Gregory 1968 discusses, terminology in this area is overlapping and problematic. I return to the issue of terminological confusion below. For seminal papers on register and genre, including detailed argumentation for a stratified model of context, see Martin 2012a, [b]; application of the model to a range of school and workplace settings is illustrated in Christie & Martin 1997.

One important implication of treating genre and register as supervenient strata is that they are conceived as emergently complex patterns of meaning. They are higher levels of meaning in other words that metaredound with lower ones – so that genre is a pattern of register patterns, register a pattern of discourse semantics ones, which are in turn a pattern of lexicogrammatical ones, in turn a pattern of phonological ones (for metaredundancy see Lemke 1995). We thus need to be very cautious as far as making generalisations about genre on the basis of discourse semantic patterns, without taking register into account – just as basing register analysis directly on grammatical patterns would leave a whole stratum of articulation, discourse semantics, out of the picture. No one would think of basing a discourse analysis simply on phonological analysis, leaving out lexicogrammar. But as noted above it is very common for SFL and corpus linguists to base context analysis simply on lexicogrammatical patterns, setting aside discourse semantics, or register (i.e. field, tenor and mode), or both, as if these levels of articulation were not crucial. Supervenience demands a full spectrum of analyses, across the strata proposed – for which, fortunately, SFL is very well provisioned (e.g. Martin & Rose 2008 for genre, Martin 1992a for register, Martin & Rose 2003 for discourse semantics, Halliday 1985a for lexicogrammar and Halliday & Greaves 2008 for intonation). Coming to terms with this extravagant tool-kit is of course a life-long learning task.

In my 1984 article, ‘Language, register and genre’, which was commissioned by Fran Christie to introduce register and genre theory to an education audience, I made analogy between the stratified approach to context just outlined and Malinowski’s concepts of context of situation (Malinowski 1923, 1935) and context of culture (Malinowski 1935). This was perhaps stretching a point, since Malinowski’s perspective was arguably more circumvenient than supervenient – but I made the suggestion, suitably hedged (I thought), as follows:

In a sense this takes us back to Malinowski, who argued that contexts both of situation and culture were important if we are to fully interpret the meaning of a text. Informally speaking, we might suggest that our level of genre corresponds roughly to context of culture in his sense (culture as a system of genres in other words), our register perhaps to his context of situation. (Martin 1984/2010:19)

As many readers seemed to find this analogy helpful, and took it up in education work (e.g. Derewianka 1990: 19), I continued to use the terms context of culture and context of situation as glosses on genre and register in at least two publications (the relevant quotes are reproduced below from Martin 1992a and Eggins & Martin 1997). By Martin 1997, thanks to Matthiessen’s 1993 clarifications, I came to appreciate the confusion that this analogy had created (which few other than Matthiessen seemed to find intriguing) – because of Halliday’s (e.g. 2002) use of the terms context of culture and context of situation for instantiation, not supervenience. The problem is discussed in the third quote below. Since the terms context of culture and context of situation had never been theoretical categories in my model, but simply intertextual glosses on genre and register, I tried to avoid them in subsequent publications.

The sociosemantic organisation of context has to be considered from a number of different angles if it is to give a comprehensive account of the ways in which meanings configure as text. Seen from the perspective of language, context can be interpreted as reflecting metafunctional diversity… Halliday 1978:122 outlines the semiotic structure of context as follows: “The semiotic structure of the situation is formed out of the three sociosemiotic variables of field, tenor and mode.” … Seen from the perspective of culture on the other hand, context can be alternatively interpreted as a system of social processes. This for example is the perspective that underlies much of Bakhtin’s writing on genre… The tension between these two perspectives will be resolved in this chapter by including in the interpretation of context two communication planes, genre (context of culture) and register (context of situation), with register functioning as the expression form of genre, at the same time as language functions as the expression form of register. (1992a: 494–495)

In this chapter we have explained how R> views text, and therefore the lexical, grammatical and semantic choices which constitute it, as both encoding and construing the different layers of context in which the text was enacted. The terms register (context of situation) and genre (context of culture) identify the two major layers of context which have an impact on text, and are therefore the two main dimensions of variation between texts. (Eggins & Martin 1997: 251)

It is probably fair to argue that in 1981/1982 we lacked some of the resources we needed for clarifying our perspective on genre in relation to register and language. For one thing we were just coming to terms with Lemke’s (1995) notion of metaredundancy (the notion of patterns of patterns of patterns of…) and how it could be applied to interstratal relations. For another, Halliday’s grammar was still growing beyond the 15 page hand-out stage, and so our appreciation of the significance of the Token/Value relation in relational clauses as a tool for thinking about layers of abstraction was inadequate. Beyond this we were probably unhelpfully vague about the distinction between realisation as an inter-stratal or inter-rank relationship and instantiation (also called realisation) as the manifestation of system in process (of systemic potential in textualised actual). This may have masked for us the way in which Halliday was managing the relationship between context of culture and context of situation at the time, which he saw as related by realisation, meaning instantiation; whereas when our educational colleagues talked about context of culture (i.e. genre) realised in context of situation (i.e. register) they meant inter-stratal realisation, not instantiation. (Martin 1997: 34–35)

Halliday’s (Halliday 2002/2005b: 254) instantiation/stratification matrix clarifies the variables at play here – omitting an expression form stratum (phonology or graphology) and including the notion of a sub-system or instance type along the instantiation cline. In a subsequent diagram in the same paper, context of culture is glossed as “potential clusters of values of field, tenor, mode” and context of situation as “instantial values of field, tenor and mode” (2002/2005b: 255) (Figure 17).

It should be stressed here that the ‘confusion’ around the terms context of culture and context of situation is purely terminological – and that both Halliday and I were recontextualising Malinowski’s own views, via Firth’s reading of them (Firth 1957b). There is nothing theoretically or descriptively at stake here in the terminology as far as my model of context and Halliday’s is concerned. All strata instantiate, including register and genre, in my stratified model of context (Martin 2010c), just as context of culture instantiates (as context of situation) and semantics, lexicogrammar and phonology instantiate as text in his; there is no disagreement there. Where there is disagreement, what is at stake is whether we need a stratified model of context or not – for Halliday, no; for me, yes, absolutely. It is important in discussions of context to concentrate substantively on what matters (i.e. whether to map genre as an emergently complex pattern of field, tenor and mode configurations or not), and not to dwell terminologically on what does not. For further clarificationc see the introductions to Martin 2012a, [b] and papers therein.

Appraisal

By the late 1980s our stratified approach to context and content planes afforded both the impulse and the possibility for work on the language of evaluation. The push from context came from our work on story genres, where as Labov had stressed (Labov & Waletzky 1967, Labov 1982, 1984) the point of a story depends on the interaction of evaluative language with ideational meaning. Plum’s and Rothery’s work developing our understanding of recounts, anecdotes, exemplums, observations, narratives of personal experience and thematic narratives (for an overview of and references to their seminal work see Martin & Rose 2008) emphasised the importance of the type of evaluation used as well as its placement in genre structure as far as distinguishing types of story genre was concerned. And we quickly realised that our framework for analysing attitude in discourse was not up to the demands being placed upon it. Accordingly we set to work developing appraisal theoryd, for my part in a series of publications leading up to Martin & White 2005 (Martin 1992a surveys grading resources in Englishe; Martin 1992a, [b], 1996 focus on affect, subsuming judgement and appreciation; Martin 1997, 2000 factor attitude into affect, judgement and appreciation, alongside engagement and amplification; Martin & White 2005 rework amplification as graduation, to make way for both force and focus systems).

The educational linguistics focus of our Write it Right research team (Rose & Martin 2012) meant that we did not have the time or resources to explore evaluation from a corpus perspective, following on from Sinclair’s development of Firth’s concept of collocation (Firth 1957a, Halliday 1966, Sinclair 1966); for an overview of research adopting this perspective see Hunston 2011. The alternative ‘lexis as delicate grammar’ perspective, initially conceived by Halliday 1961 and best illustrated in Hasan 1987, also gave us pause. As the function/rank matrix in Figure 8 above shows, relevant evaluative meaning for Halliday was in fact scattered across a range of lexicogrammatical systems – including at least process type (affective mental processes) at clause rank, attitude in nominal groups, comment in adverbial groups and connotation for words. This reflects the fact that a feeling like happiness can be realised through many different systems (happily they lost, it cheered him they lost, he felt happy, a happy chappy, his happiness etc.). As discourse analysts we wanted a system that would generalise across these diverse lexicogrammaticalisations, bringing feelings together in relation to one another so that we could describe prosodies of evaluation in relation to genre (and later on in relation to the tenor of face-to-face interaction and the negotiation of identity; Eggins & Slade 1997, Martin 2010c). This meant turning from a grammatical perspective on evaluation to a discourse semantic one.

The natural place to do this was as a partner to speech function and negotiation systems (Martin 1992a, Martin & Rose 2003/2007) in the interpersonal metafunction (as articulated in Figure 10 above). Appraisal, as we came to call it, would there complement the interactive turn-taking focus of those two mood based systems, highlighting the ‘-personal’ dimension of interpersonal meaning. That said, we of course recognised that feelings are expressed to be shared; they are a resource for bonding (Martin et al. 2013). So their ‘inter-personality’ is crucial to understanding their use. An outline of appraisal resources is presented as Figure 18 below, including types of attitude (affect, judgement and appreciation), grading systems (force and focus) and engagement systems for sourcing attitudes and managing heteroglossia in discourse.

The critical point here as far as this paper is concerned, is that without a stratified content plane there would have been no way to generalise appraisal resources across the various lexicogrammatical systems realising them, including incongruent realisations (involving grammatical metaphor). And by treating discourse semantic systems as organised by metafunction, we were able to reinterpret from an interpersonal perspective resources that are experientially constituted in lexicogrammar (i.e. mental processes and states of affection – e.g. He disliked the approach/He was unhappy about the approach). Our interpersonal discourse semantic approach also oriented us to the prosodic nature of the realisation of attitude in discourse, as developed by Hood in her work on academic writing (Hood 2006, 2010).

In short then, our genre work was the trigger, and our discourse semantic perspective the affording scaffold – for the evolution of a new approach to interpersonal meaning in SFL, expanding the move and exchange structure focus of earlier research (e.g. Halliday 1984, Ventola 1987, Martin 1992a, [b]). Significantly, this gave us extended resources for analysing interpersonal meaning in monologic text (which is usually after all simply a succession of basically declarative statements from the perspective of mood and speech function). It also gave us improved resources for analysing the solidarity dimension of tenor, since empathy in relation to feeling is such an important resource for negotiating social affinity. And it gave us tools for distinguishing story genres from one another and appreciating the significance of prosodic phases of evaluation in their structure. Ongoing work in the 1990s on history and media discourse, and literary and fine art criticism, was both enriched by and in turn enriched our model of feeling in discourse (e.g. Coffin 2006, Iedema et al. 1994, Rothery & Stenglin 2000).

Voices

As forecast in “Disciplinarity” above in this paper I have tried to illustrate how a disciplinary singular like SFL might resist the tendency of horizontal knowledge structures to fragment into competing theories and instead evolve, subsuming its past into possible futures. With reference to my work on discourse semantics, genre and appraisal I have tried to show how SFL has been expanded theoretically, via a recontextualisation of previous descriptions in relation to an expanding set of linguistic phenomena (as crudely imaged in Table 1). And in “My training” above I set the ground for these developments by commenting on my training. To understand why I reasoned the way I did in other words you have to know where I was coming from – my time, my place, my teachers, my goals.

A short-hand way of thinking about this dialectic of evolution and personal history would be to think of discourse semantics as my mediation of a conversation between Gleason and Halliday, register and genre as mediation of a conversation between Gregory and Halliday, and appraisal as mediation of a conversation between Labov and Halliday. And by personalising my historyf I hope I have been able to show that there was more than a disjunction of ideas involved. Gregory, Gleason and Halliday were more than ideas for me; they were inspirational role models – to various degrees they related to me as mentors, colleagues, comrades and friends. An axiological charged epistemology was at play throughout the mediation, and will remain so, I am sure, for as long as I can sustain a comparable dialectic of change. I am equally sure my teachers would say the same of the ancestors they read and got me to read.

Appliable linguistics

As noted in “Singulars and regions” above, in this paper I have concentrated on the evolution of a singular, SFL, rather than the emergence of a region. So I have not for example considered the range of singulars at play in the development of the educational linguistics region known as the Sydney School (Rose & Martin 2012). An outline of one reading of the key singulars influencing this particular curriculum and pedagogy paradigm is presented in Figure 19 g, which does not of course specify which particular aspects of the knowledge of each singular were brought into play.

It would be remiss of me however not to position the evolution of discourse semantics, register and genre, and appraisal without acknowledging my commitment to Halliday’s conception of SFL as an appliable linguistics (Halliday 2008). My approach to discourse semantics was first developed in relation to research in clinical linguistics (Rochester & Martin 1979); it continued to develop in relation to action research in educational linguistics, which was also the applied context for the evolution of register and genre as a stratified model of context (Rose & Martin 2012), and of appraisal as a model of evaluation in discourse (Martin & White 2005). More recently my work in forensic linguistics (Martin 2010c) has focused my attention on the need for work on instantiation and individuation as hierarchies complementary to stratification (Martin 2010c). All this accords, I believe, with Halliday’s early 1950s dream of a Marxist linguistics which would be “a socially accountable linguistics, and this in two distinct though related senses: that it put language in its social context, and at the same time it put linguistics in its social context, as a mode of intervention in critical social practices.” (1993: 73). This quote of course has always resonated for me with another one, again from Halliday, which I first heard at the International Systemic Functional Congress at York University in Toronto in 1982: “From Bernstein I learnt also, for the second time in my life, that linguistics cannot be other than an ideologically committed form of social action.” (Halliday 1985b: 5) I doubt very much that SFL could have survived, let alone evolved and thrived, without a serious political commitment of this order. I certainly could not have; that much of my life at least is more than clear.

Endnotes

aI am indebted to Chris Cleirigh for both the terms and the attendant imaging, although he does not currently use the terms in the sense I am deploying them here.

bAccording to Ventola 1987, this group included Suzanne Eggins, Chris Nesbitt, Guenter Plum, Cate Poynton, Lynn Poulton, Joan Rothery, Anne Thwaite, Eija Ventola and myself.

cMartin 2013a reviews the development of work on context in SFL in relation to both language and attendant modalities of communication.

dThe Write it Right research team, whose work I directed (see Rose & Martin 2012), played key roles in this development, including Caroline Coffin, Susan Feez, Sally Humphrey, Rick Iedema, Henrike Koerner, David McInnes, David Rose, Joan Rothery, Maree Stenglin, Peter White and Robert Veel; relevant publications and the later contributions by Gillian Fuller (on engagement) and Sue Hood (on graduation) developing the framework are acknowledged in Martin & White 2005.

eThis survey can be usefully compared to Labov’s 1984 profile of what he calls intensity.

fThe significance of personal history as far as a deeper appreciation of Halliday’s work is concerned is flagged in the collection of interviews recently published by Continuum as Interviews with Michael Halliday: language turned back on himself (Martin 2013b).

gIn Figure 19, MCA refers to the ‘mind, culture, activity’ theory of neo-Vygotsykans (see Wells 1994, 1996 for discussion); for neo-Bernsteinian Social Realism see Maton 2014.

References

Bernstein B: Pedagogy, Symbolic Control and Identity: theory, research, critique. London: Taylor & Francis; 1996. [Revised Edition 2000]

Bernstein B: Vertical and horizontal discourse: an essay. British Journal of Sociology of Education 1999,20(2):157–173. 10.1080/01425699995380

Cha JS: Before and Towards Communication Linguistics: essays by Michael Gregory and associates. Seoul: Department of English Language and Literature, Sookmyung Women’s University; 1995.

Christie F, Martin JR (Eds): Genre and Institutions: social processes in the workplace and school. London: Cassell (Open Linguistics Series); 1997.

Christie F, Martin JR (Eds): Knowledge Structure: functional linguistic and sociological perspectives. London: Continuum; 2007.

Christie F, Maton K (Eds): Disciplinarity: functional linguistic and sociological perspectives. London: Continuum; 2011.

Coffin C: Historical Discourse: the language of time, cause and evaluation. London: Continuum; 2006.

Cromack RE: Language Systems and Discourse Structure in Cashinawa (Hartford Studies in Linguistics 23). Hartford, Conn.: Hartford Seminary Foundation; 1968.

Villiers J de, Stainton R (Eds): Papers in Honour of Michael Gregory In Communication in Linguistics. Volume 1. Toronto: Éditions du GREF; 2001.

Villiers J de, Stainton R (Eds): Vol. 2 of Communication in Linguistics In Michael Gregory’s Proposals for a Communication Linguistics. Toronto: Éditions du GREF; 2009.

Derewianka B: Exploring How Texts Work. Sydney: Primary English Teaching Association; 1990.

Eggins S, Martin JR: Genres and registers of discourse. In Discourse as Structure and Process. Edited by: van Dijk TA. London: Sage (Discourse Studies: a multidisciplinary introduction. Volume 1); 1997:230–256. [reprinted in Martin 2012a. 161–186]

Eggins S, Slade D: Analysing Casual Conversation. London: Cassell; 1997. [reprinted Equinox 2005]

Ellis J, Ure J: Language varieties: register. In Encyclopedia of Linguistics: information and control. Edited by: Meetham AR. Oxford: Pergamon; 1969:251–259.

Firth JR: A Synopsis of Linguistic Theory, 1930–1955. In Studies in Linguistic Analysis (Special volume of the Philological Society). London: Blackwell; 1957a:1–31. [reprinted in F R Palmer 1968 [Ed.] Selected Papers of J R Firth, 1952–1959. London: Longman. 168–205]

Firth JR: Ethnographic analysis and language with reference to Malinowski’s views. In Man and Culture: an evaluation of the work of Bronislaw Malinowski. Edited by: Firth RW. London; 1957b:93–118. Routledge & Kegan Paul [reprinted in F R Palmer 1968 [Ed.] Selected Papers of J R Firth, 1952–1959. London: Longman. 137–167]

Gleason HA Jr: An Introduction to Descriptive Linguistics. New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston; 1961.

Gleason HA Jr: Contrastive analysis in discourse structure. Monograph Series on Languages and Linguistics 21 (Georgetown University Institute of Languages and Linguistics). 1968. [reprinted in Makkai & Lockwood 1973:258–276]

Gregory M: Aspects of varieties differentiation. Journal of Linguistics 1967, 3: 177–198. 10.1017/S0022226700016601

Gregory M: Describing English. de Villiers & Stainton. 2009, 34–142.

Gregory M, Carroll S: Language and Situation: language varieties and their social contexts. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul; 1978.

Gutwinski W: Cohesion in Literary Texts: a study of some grammatical and lexical features of English discourse. The Hague: Mouton (Janua Linguarum Series Minor 204); 1976.

Halliday MAK: Categories of the theory of grammar. Word 1961,17(3):241–292. [reprinted in Halliday, MAK. 1976. Halliday: system and function in language (Selected papers edited by Gunther Kress). Oxford: Oxford University Press: 52–72 and Halliday 2002a:37–94].

Halliday MAK: Lexis as a linguistic level. Memory of J R Firth. Edited by: Bazell CE, Catford JC, Halliday MAK. London: Longman; 1966:148–162.

Halliday MAK: Options and functions in the English clause. Brno Studies in English 1969, 8: 81–88. [reprinted in Halliday, MAK, and JR Martin (eds.). 1981. Readings in Systemic Linguistics. London: Batsford. 138–145 and Halliday, MAK. 2005a. Studies in English Language (Volume 7 in the Collected Works of M A K Halliday edited by Jonathan Webster). London: Continuum. 254–163]

Halliday MAK: Explorations in the Functions of Language. London: Edward Arnold; 1973.

Halliday MAK: Language as a Social Semiotic: the social interpretation of language and meaning. London: Edward Arnold; 1978.

Halliday MAK: Modes of meaning and modes of expression: types of grammatical structure, and their determination by different semantic functions. In Function and Context in Linguistics Analysis: essays offers to William Haas. Edited by: Allerton DJ, Carney E, Holcroft D. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 1979:57–79. [reprinted in Halliday, MAK. 2002a. On Grammar (Volume 1 in the Collected Works of M A K Halliday edited by Jonathan Webster). London: Continuum. 196–218]

Halliday MAK: Language as code and language as behaviour: a systemic-functional interpretation of the nature and ontogenesis of dialogue. In The Semiotics of Language and Culture: Vol 1: Language as Social Semiotic. Edited by: Fawcett R, Halliday MAK, Lamb SM, Makkai A. London: Pinter; 1984:3–35. [reprinted in Halliday, MAK. 2003. The Language of Early Childhood (Volume 4 in the Collected Works of M A K Halliday edited by Jonathan Webster). London: Continuum. 226–249]

Halliday MAK: An Introduction to Functional Grammar. London: Edward Arnold; 1985a. [revised 2nd edition 1994; revised 3rd edition, with C M I M Matthiessen 2004]

Halliday MAK: Systemic background. In Systemic Perspectives on Discourse: selected theoretical papers from the 9th International Systemic Workshop. Edited by: Benson JD, Greaves WS. Norwood, N.J: Ablex (Advances in Discourse Processes 15); 1985b:1–15. [reprinted in Halliday, MAK. 2003a. The Language of Early Childhood (Volume 4 in the Collected Works of M A K Halliday edited by Jonathan Webster). London: Continuum. 185–198]

Halliday MAK: Computing meaning: some reflections on part experience and present prospects. In Discourse and Language Functions. Edited by: Huang GW, Wang ZY. Shanghai: Foreign Language Teaching and Research Press; 2002:3–25. [reprinted in Halliday, MAK. 2005b. Computational and Quantitative Studies (Volume 6 in the Collected Works of M A K Halliday edited by Jonathan Webster). London: Continuum. 2005: 239–267]

Halliday MAK: Working the meaning: towards an appliable linguistics. Meaning in Context: strategies for implementing intelligent applications of language studies. Edited by: Webster J. London: Continuum; 2008:7–23.

Halliday MAK, Greaves WS: Intonation in the Grammar of English. London: Equinox; 2008.

Halliday MAK, Hasan R: Coheson in English. London: Longman (English Language Series 9); 1976.

Halliday MAK, Hasan R: Text and Context: aspects of language in a social-semiotic perspective. Sophia Linguistica VI. Tokyo: The Graduate School of Languages and Linguistics & the Linguistic Institute for International Communication, Sophia University; 1980. [new edition published as M A K Halliday & R Hasan 1985 Language, context, and text: aspects of language in a social-semiotic perspective. Geelong, Vic.: Deakin University Press] [republished by Oxford University Press 1989]

Halliday MAK, Matthiessen CMIM: Construing Experience through Language: a language-based approach to cognition. London: Cassell [republished by Continuum 2006]; 1999.

Halliday MAK, McIntosh A, Strevens P: The Linguistic Sciences and Language Teaching. London: Longman (Longmans’ Linguistics Library); 1964.

Hasan R: Text in the systemic-functional model. In Current Trends in Textlinguistics. Edited by: Dressler W. Berlin: Walter de Gruyter; 1977:228–246.

Hasan R: On the notion of text. In Text vs Sentence: basic questions of textlinguistics. Edited by: Petöfi JS. Hamburg: Helmut Buske (Papers in Textlinguistics 20.2); 1979:369–390.

Hasan R: The grammarian’s dream: lexis as most delicate grammar. In New Developments in Systemic Linguistics Vol. 1: theory an description. Edited by: Halliday MAK, Fawcett RP. London: Pinter; 1987:184–211. [reprinted in R Hasan 1966 Ways of Saying: ways of meaning (Selected Papers of Ruqaiya Hasan edited by C Cloran, D Butt & G Williams). London: Cassell. 73–103]

Hasan R: Semantic Variation: meaning in society and sociolinguistics. London: Equinox (The Collected Works of Ruqaiya Hasan, edited by Jonathon Webster, Vol. 2); 2009.

Hjelmslev L: Structural analysis of language. Studia Linguistica 1947, 1: 69–78. 10.1111/j.1467-9582.1947.tb00360.x

Hjelmslev L: Prolegomena to a Theory of Language. Madison, Wisconson: University of Wisconsin Press; 1961.

Hood S: The persuasive power of prosodies: radiating values in academic writing. Journal of English for Academic Purposes 2006, 5.1: 37–49.

Hood S: Appraising Research: evaluation in academic writing. London: Palgrave; 2010.

Hunston S: Corpus approaches to Evaluation: phraseology and evaluative language. London: Routledge; 2011.

Hyon S: Genre in three traditions: implications for ESL. TESOL Quarterly 1996,30(4):693–722. 10.2307/3587930

Iedema R, Feez S, White P: Media Literacy (Write it Right Literacy in Industry Research Project - Stage 2). Sydney: Metropolitan East Disadvantaged Schools Program; 1994:322. [reprinted Sydney: NSW Adult Migrant English Service 2008]

Labov W: Speech actions and reactions in personal narrative. In Analaysing Discourse: text and talk (Georgetown University Round Table on Language and Linguistics 1981). Edited by: Tannen D. Washington, D.C: Georgetown University Press; 1982.

Labov W: Intensity. In Meaning, Form, and Use in Context: linguistic applications (Georgetown University Roundtable on Language and Linguistics). Edited by: Schiffrin D. Washington, D.C: Geogretown University Press; 1984:43–70.

Labov W, Waletzky J: Narrative analysis: oral versions of personal experience. In Essays on the Verbal and Visual Arts (Proceedings of the 1966 Spring Meeting of the American Ethnological Society). Edited by: Helm J. Seattle: University of Washington Press; 1967:12–44. [republished in Bamberg, GW. 1997. Oral versions of personal experience: three decades of narrative analysis. Journal of Narrative and Life History: 1–4. London: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.]

Lamb S: Epilegomena to a theory of language. Romance Philology 1966, XIX4: 531–573.

Lemke JL: Textual Politics: discourse and social dynamics. London: Taylor & Francis; 1995.

Lockwood DG: Introduction to Stratificational Linguistics. New York: Harcourt, Brace, Jovanovich; 1972.

Makkai A, Lockwood D: Readings in Stratificational Linguistics. University, Al: Alabama University Press; 1973.

Malinowski B: The problem of meaning in primitive languages. Supplment I to C K Ogden & I A Richards The Meaning of Meaning. New York: Harcourt Brace & World; 1923:296–336.

Malinowski B: Coral Gardens and their Magic. London: Allen & Unwin; 1935.

Martin JR: The development of register. In Developmental Issues in Discourse. Edited by: Freedle RO, Fine J. Norwood, N J: Ablex (Advances in Discourse Processes 10); 1983:1–40. [reprinted in Martin, JR. 2012b. Register Studies. Vol. 4: Collected Works of J R Martin (Wang Zhenhua Ed.). Shanghai: Shanghai Jiao Tong University Press. 9–46]

Martin JR: Language, register and genre. In Children Writing: reader. Edited by: Christie F. Geelong, Vic: Deakin University Press (ECT Language Studies: children writing) 2001/2010 21–30; 1984. [revised for A Burns & C Coffin [Eds.] Analysing English in a Global Context: a reader. Clevedon: Routledge (Teaching English Language Worldwide) 2001. 149–166] [further revised for C Coffin, T Lillis, & K O’Halloran [Eds.] Applied linguistics methods: a reader. London: Routledge. 2010. 12–32]

Martin JR: Factual Writing: exploring and challenging social reality. Geelong, Vic: Deakin University Press [republished London: Oxford University Press. 1989]; 1985b.

Martin JR: Grammaticalising ecology: the politics of baby seals and kangaroos. In Language, Semiotics, Ideology. Edited by: Threadgold T, Grosz EA, Kress G, Halliday MAK. Sydney: Sydney Association for Studies in Society and Culture (Sydney Studies in Society and Culture 3); 1986a:225–268. [reprinted in Martin, JR. 2012d. CDA/PDA. Vol. 6: Collected Works of J R Martin (Wang Zhenhua Ed.). Shanghai: Shanghai Jiao Tong University Press: 7–49]

Martin: Intervening in the process of writing development. In Writing to Mean: teaching genres across the curriculum. Applied Linguistics Association of Australia (Occasional Papers 9) Edited by: Painter C, Martin JR. 1986b, 11–43. [reprinted in Martin, JR. 2012c. Language in Education. Vol. 7: Collected Works of J R Martin (Wang Zhenhua Ed.). Shanghai: Shanghai Jiao Tong University Press: 102–132].

Martin JR: English text: system and structure. Amsterdam: Benjamins; 1992.

Martin JR: Macroproposals: meaning by degree. In Discourse Description: diverse analyses of a fund raising text. Edited by: Mann WA, Thompson SA. Amsterdam: Benjamins; 1992b:359–395. Martin, JR. 2012c. Discourse Analysis. Vol. 5: Collected Works of J R Martin (Wang Zhenhua Ed.). Shanghai: Shanghai Jiao Tong University Press: 133–166]

Martin JR: Analysing genre: functional parameters. Genre and Institutions: social processes in the workplace and school. Edited by: Christie F, Martin JR. London: Cassell (Open Linguistics Series). 3–39. [Japanese translation by Hiro Tsukada published in Shidonii Gakuha no SFL: Haridei Gengo Riron no Tenkai, ed. Analysing genre: functional parameters. Christie & Martin. Tokyo: Liber Press. 2005. 3–39]; 1997.

Martin JR: Beyond exchange: appraisal systems in English. In Evaluation in Text: authorial stance and the construction of discourse. Edited by: Hunston S, Thompson G. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2000:142–175. [reprinted in Martin, JR. 2010. Discourse Semantics. Vol. 2 in the Collected Works of J R Martin (Wang Zhenhua Ed). Shanghai: Shanghai Jiao Tong University Press: 203–245]

Martin JR: Metafunctional profile: Tagalog. Language Typology: a functional perspective. Edited by: Caffarel A, Martin JR, Matthiessen CMIM. Amsterdam: Benjamins; 2004:255–304.

Martin JR: Systemic Functional Linguistic Theory. Vol. 1: Collected Works of J R Martin (Wang Zhenhua Ed.). Shanghai: Shanghai Jiao Tong University Press; 2010a.

Martin JR: Discourse Semantics. Vol. 2: Collected Works of J R Martin (Wang Zhenhua Ed.). Shanghai: Shanghai Jiao Tong University Press; 2010b.

Martin JR: Semantic variation: modelling system, text and affiliation in social semiosis. New Discourse on Language: functional perspectives on multimodality, identity and affiliation. Edited by: Bednarek M, Martin JR. London: Continuum; 2010c:1–34.

Martin JR: Metalinguistic divergence: centrifugal dimensionality in SFL. Annual Review of Functional Linguistics (Higher Education Press, Beijing) 2011, 3: 8–32.

Martin JR: Genre Studies. Vol. 3: Collected Works of J R Martin (Wang Zhenhua Ed.). Shanghai: Shanghai Jiao Tong University Press; 2012a.

Martin JR: Register Studies. Vol. 4: Collected Works of J R Martin (Wang Zhenhua Ed.). Shanghai: Shanghai Jiao Tong University Press; 2012.

Martin JR: Modelling context: matter as meaning. In Languages, metalanguages, modalities, cultures: functional and socio-discursive perspectives. Edited by: Gouveia C, Alexandre M. Lisbon: BonD & ILTEC; 2013a:10–64.

Martin JR (Ed): Interviews with Michael Halliday: language turned back on himself. London: Bloomsbury; 2013.

Martin JR, Plum G: Construing experience: some story genres. Journal of Narrative and Life History 1997, 7: 1–4. (Special Issue: Oral Versions of Personal Experience: three decades of narrative analysis; M Bamberg Guest Editor). 299–308. [reprinted in Martin, JR. 2012a. Genre Studies. Vol. 3: Collected Works of J R Martin (Wang Zhenhua Ed.). Shanghai: Shanghai Jiao Tong University Press. 152–160]

Martin JR, Rose D: Working with Discourse: meaning beyond the clause. 2nd edition. London: Continuum; 2003. [2nd revised edition 2007]

Martin JR, Rose D: Genre Relations: mapping culture. London: Equinox; 2008.

Martin JR, White PRR: The Language of Evaluation: appraisal in English. London: Palgrave; 2005.

Martin JR, Zappavigna M, Dwyer P, Cleirigh C: Users in uses of language: embodied identity in Youth Justice Conferencing. Text & Talk 2013,33(4/5):467–496. JR Martin, M Zappavigna, and P Dwyer. [reprinted in Martin, JR. 2012f. Forensic Linguistics. Vol. 8: Collected Works of J R Martin (Wang Zhenhua Ed.). Shanghai: Shanghai Jiao Tong University Press. 258–288]

Martinet A: La double articulation linguistique. Travaux de la Societé Linguistique de Copenhague 1949, 5: 30–37.

Maton K: Knowledge-knower structures in intellectual and educational fields. in Christie & Martin. London: Continuum; 2007:87–108.

Maton K: Knowledge and Knowers: towards a realist sociology of education. London: Routledge; 2014.

Maton K, Muller J: A sociology for the transmission of knowledges. in Christie & Martin. London: Continuum; 2007:14–33.

Maton K, Hood S, Shay S (Eds): Knowledge-building: educational studies in legitimation code theory.

Matthiessen CMIM: Register in the round: diversity in a unified theory of register analysis. In Register Analysis: theory and practice. Edited by: Ghadessy M. London: Pinter; 1993:221–292.

Matthiessen CMIM, Halliday MAK: Systemic Functional grammar: a first step into the theory. Beijing: Higher Education Press; 2009.

Muller J: Reclaiming Knowledge: social theory, curriculum and education policy. London: Routledge (Knowledge, Identity and School Life Series 8); 2000.

Muller J: On splitting hairs: hierarchy, knowledge and the school curriculum. in Christie & Martin. 2007, 64–86.

Pike KL: Linguistic concepts: an introduction to tagmemics. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press; 1982.

Pike KL, Pike EG: Text and Tagmeme. London: Pinter; 1983.

Plum G: Text and contextual conditioning in spoken English: A genre-based approach. Vols 1 & 2. Nottingham: Department of English Studies, University of Nottingham (Monographs in Systemic Linguistics); 1988.

Rochester S, Martin JR: Crazy talk: a study of the discourse of schizophrenic speakers. New York: Plenum; 1979.

Rose D, Martin JR: Learning to write, reading to learn: genre, knowledge and pedagogy in the Sydney School. London: Equinox; 2012.

Rothery J: Making changes: developing an educational linguistics. 1996, 86–123. Hasan, R & G Williams [Eds.] 1996 Literacy in Society. London: Longman

Rothery J, Stenglin M: Interpreting literature: the role of APPRAISAL. In Researching Language in Schools and Functional Linguistic Perspectives. Edited by: Unsworth L. London: Cassell; 2000:222–244.

Saussure F: Course in General Linguistics. New York: McGraw-Hill; 1916/1966.

Sinclair JMH: Beginning the study of lexis. 1966, 410–430. Bazell, CE, JC Catford and MAK Halliday [Eds.] 1966 In Memory of J R Firth. London: Longman

Spencer J, Gregory M: An approach to the study of style. In Linguistics and Style. Edited by: Spencer J. London: Oxford University Press; 1964:57–105.

Stennes LH: The Identification of Participants in Adamawa Fulani (Hartford Studies in Lingusitics 24). Hartford, Conn.: Hartford Seminary Foundation; 1969.

Taber CR: The Structure of Sango Narrative (Hartford Studies in Linguistics 17). Hartford Conn.: Hartford Seminary Foundation; 1966.

Ure J, Ellis J: Register in descriptive linguistics and linguistic sociology. In Issues in Sociolinguistics. Edited by: Uribe-Villas O. The Hague: Mouton; 1977:197–243.

Ventola E: The Structure of Social Interaction: a systemic approach to the semiotics of service encounters. London: Pinter; 1987.

Wells G: The complementary contributions of Halliday and Vygotsky to a “language-based theory of learning. Linguistics and Education 1994, 6: 41–90. 10.1016/0898-5898(94)90021-3

Wells G: Using the tool-kit of discourse in the activity of teaching and learning. Mind Culture Activity 1996,3(2):74–101. 10.1207/s15327884mca0302_2

Wignell P: Vertical and horizontal discourse and the social sciences. in Christie & Martin. 2007, 184–204.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The author declares that he has no competing interests.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Martin, J.R. Evolving systemic functional linguistics: beyond the clause. Functional Linguist. 1, 3 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1186/2196-419X-1-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/2196-419X-1-3