Abstract

Background

International accreditations of drug regulatory authorities not only lead to improvement in their functioning but pharmaceutical firms are also benefited. The aim of this study is to identify aspects that should be improved for the purpose of international accreditation and recognition of Drug Regulatory Authority of Pakistan (DRAP).

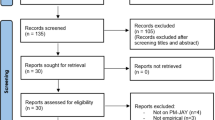

Methods

A qualitative study was conducted from May 1, 2017, to July 31, 2017. The data were collected from officials working in DRAP through in-depth semistructured interviews. The respondents were recruited through a convenience sampling strategy. The sample size was determined by using the saturation point criterion. Data were analyzed to draw conclusions using inductive thematic analysis.

Results

A total of 12 officials working in DRAP were interviewed. Analysis of the data yielded 25 categories, 10 subthemes, and 3 themes. The themes were administrative barriers, operational barriers, and future aspects of international accreditation. The subthemes related to administrative barriers included human resource, lack of harmonization and coordination, transparency and accountability, and improper resource allocation. The subthemes related to operational barriers included procedures and policies, deficit of testing laboratories and equipment, reporting system for adverse drug reactions, and external factors influencing the functioning of DRAP. The subthemes related to future aspects of international accreditation included advantages associated with international accreditation and time required to achieve this goal.

Conclusions

There is a huge scope of improvement in the functioning of DRAP and the identified barriers must be dealt with timely to make it happen.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

World Health Organization. Regulatory system strengthening. World Health Organization, http://www.who.int/medicines/regulation/rss/en/. Published 2018. Accessed June 27, 2018.

World Health Organization. WHO Global Benchmarking Tool (GBT) for evaluation of national regulatory systems. World Health Organization, http://www.who.int/medicines/regulation/benchmarking_tool/en/. Published 2017. Accessed June 27, 2018.

World Health Organization. Prequalification of quality control laboratories: procedure for assessing the acceptability, in principle, of quality control laboratories for use by United Nations agencies. World Health Organization, http://www.who.int/medicines/services/expertcommittees/pharmprep/QAS06_171_RevPrequal_QCLabs.pdf. Published 2006. Accessed June 27, 2018.

PIC/S. Introduction: Pharmaceutical Inspection Co-operation Scheme (PIC/S). Pharmaceutical Inspection Co-operation Scheme (PIC/S). https://www.picscheme.org/en/about. Published 2016. Accessed June 27, 2018.

Rashid H. Impact of the Drug Regulatory Authority in Pakistan: an evaluation. New Visions Public Aff. 2015;7:50-61.

Saqib A, Atif M, Ikram R, Riaz F, Abubakar M, Scahill S. Factors Affecting patients’ knowledge about dispensed medicines: a qualitative study of healthcare professionals and patients in Pakistan. PLoS One. 2018;13(6):e0197482.

Boyatzis RE. Transforming Qualitative Information: Thematic Analysis and Code Development. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1998.

Starks H, Brown Trinidad S. Choose your method: a comparison of phenomenology, discourse analysis, and grounded theory. Qual Health Res. 2007;17(10):1372–1380.

Lincoln YS, Guba E. Naturalistic Inquiry. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage; 1985.

Atif M, Ahmad M, Saleem Q, Curley L, Qamar-uz-Zaman M. Pharmaceutical policy in Pakistan. In: Babar Z, ed. Pharmaceutical Policy in Countries With Developing Healthcare Systems. Cham: Springer; 2017:25–44.

PIC/S. Revised PIC/S audit checklist based on evaluation guide for GMP regulatory compliance programme (by Health Canada). Pharmaceutical Inspection Co-operation Scheme (PIC/S). https://www.picscheme.org/en/accessions-accession. Published 2014. Accessed June 27, 2018.

Konduri N, Rauscher M, Wang S-CJ, Malpica-Llanos T. Individual capacity-building approaches in a global pharmaceutical systems strengthening program: a selected review. J Pharma Policy Pract. 2017;10(1):16.

Allchurch MH, Barbano DBA, Pinheiro M-H, Lazdin-Helds J. Fifty years of the European Medicines Regulatory Network: reflections for strengthening intra-regional cooperation in the Region of the Americas. Rev Panam Salud Pública. 2016;39(5): 288–293.

Rose-Ackerman S, Tan Y. Corruption in the procurement of pharmaceuticals and medical equipment in China; the incentives facing multinationals, domestic firms and hospital officials. Yale Law School Legal Scholarship Repository. 2015;32: Paper 4945.

Medicines Transparency Alliance. Transparency and accountability. Medicines Transparency Alliance. http://www.medicinestransparency.org/key-issues/transparency-and-accountability/.>. Published 2017. Accessed June 27, 2018.

APP. Federal drug surveillance laboratory to start functioning soon. The Nation, February 20, 2018.

Maigetter K, Pollock AM, Kadam A, Ward K, Weiss MG. Pharmacovigilance in India, Uganda and South Africa with reference to WHO’s minimum requirements. Int J Health Policy Manag. 2015;4(5):295–305.

Essential Medicines and Health Products Information Portal. The Pathology of Negligence. Report of the judicial inquiry tribunal to determine the causes of deaths of patients of the Punjab Institute of Cardiology, Lahore in 2011-2012. World Health Organization. http://apps.who.int/medicinedocs/en/m/abstract/Js22131en/. Published 2012. Accessed October 8, 2018.

Babar Z-U-D, Jamshed SQ, Malik MA, Löfgren H, Gilani A-H. The pharmaceutical industry, intellectual property rights and access to medicines in Pakistan. In: Löfgren, H, Williams, O, ed. The New Political Economy of Pharmaceuticals: Production, Innovation and TRIPS in the Global South. London: Palgrave Macmillan; 2013:167–184.

World Health Organization. Measuring transparency to improve good governance in the public pharmaceutical sector: Pakistan. World Health Organization. http://applications.emro.who.int/docs/EMROPUB_2017_EN_19362.pdf. Published 2017. Accessed October 8, 2018.

DRAP lacks international regulatory standards. Dawn, May 4, 2016.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Ikram, R., Saqib, A., Mushtaq, I. et al. Scope of Improvement in the Functioning of National Regulatory Authority—A Step Toward International Accreditation: A Qualitative Study From Pakistan. Ther Innov Regul Sci 53, 787–794 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1177/2168479018814475

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1177/2168479018814475