修回日期: 2013-05-31

接受日期: 2013-07-03

在线出版日期: 2013-08-18

炎症性肠病(inflammatory bowel disease, IBD)的病因有很多, 其中微生物因素近来越来越受到关注. 研究发现难辨梭状芽孢杆菌感染(Clostridium difficile infection, CDI)在成人及儿童IBD患者中的发生率不断上升. 抗生素、免疫抑制剂、抑酸剂等药物可增加IBD患者发生CDI的风险, 及时检测CDI并选择有效的抗生素是治疗重点, 同时可辅以免疫及生态治疗. 本文对难辨梭状芽孢杆菌在炎症性肠病中的研究进展作一综述.

核心提示: 难辨梭状芽孢杆菌感染(Clostridium difficile infection, CDI)在成人及儿童炎症性肠病(inflammatory bowel disease, IBD)患者中的发生率不断上升. 抗生素、免疫抑制剂、抑酸剂等药物可增加IBD患者发生CDI的风险, 及时检测CDI并选择有效抗生素是治疗的重点.

引文著录: 张毅, 黄光明. 难辨梭状芽孢杆菌在炎症性肠病中的研究进展. 世界华人消化杂志 2013; 21(23): 2308-2314

Revised: May 31, 2013

Accepted: July 3, 2013

Published online: August 18, 2013

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) has many etiological factors, among which microbial factors have attracted more and more attention recently. Studies have demonstrated that the incidence of Clostridium difficile infection (CDI) in both adult and children IBD patients has been rising in recent years. Many drugs such as antibiotics, immunosuppressive agents, and acid-suppressing agents may increase the incidence of CDI. Identifying CDI and selecting effective antibiotics are keys to successful treatment, and immunological and ecological treatments are also useful choices. In this article, we will review the progress in research of CDI in IBD patients.

- Citation: Zhang Y, Huang GM. Clostridium difficile infection in patients with inflammatory bowel disease: An update. Shijie Huaren Xiaohua Zazhi 2013; 21(23): 2308-2314

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1009-3079/full/v21/i23/2308.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.11569/wcjd.v21.i23.2308

炎症性肠病(inflammatory bowel disease, IBD)是以反复发作的肠道慢性炎症为特征的一组疾病, 主要包括溃疡性结肠炎(ulcerative colitis, UC)和克罗恩病(Crohn's disease, CD). 随着对IBD发病机制研究的不断深入, 目前发现微生物因素在其起病中起到了不可忽视的作用. 近年来研究发现, 难辨梭状芽孢杆菌感染(Clostridium difficile infection, CDI)在成人及儿童IBD患者中的发生率不断上升[1,2], 推测其可能与IBD存在一定关系. 本文就难辨梭状芽孢杆菌在IBD中的研究进展做一综述.

难辨梭状芽孢杆菌为革兰阳性厌氧菌, 广泛存在于自然环境中, 1935年首次从一名婴儿的大便中分离出来, 因其培养与分离的困难而得名[3]. 他是婴儿肠道内的正常菌群, 可在婴儿粪便中检测到, 但成人检出率较低.

美国疾病控制和预防中心的数据显示, CDI的发生率从1996年的31/10万增加到2003年的61/10万[4]. 加拿大、欧洲等流行病学调查报道了相同趋势[5,6]. Clayton等[7]研究报道IBD患者CDI的发生率为8.2%, 较正常成人(1.0%)明显升高, 同时还发现UC患者的感染率高于CD患者, 分别为9.4%和6.9%. 同时CDI患者的死亡率也在上升, 每年估计有15000-20000例患者死于CDI[8], Navaneethan等[9]研究报道IBD合并CDI患者的死亡率是单纯的IBD或CDI患者死亡率的4倍.

正常人体胃肠道中存在一个十分复杂的菌群, 细菌大约有1000多种[10], 数量达1014个左右, 他们按一定的比例和顺序定植在人体肠壁上, 形成稳定的微生态平衡. 由于抗生素等因素破坏肠道原有的生物屏障, 从而导致一些内源性细菌的过度生长或对外源性病原菌易感性的增加. 其中最常见的致病菌是难辨梭状芽孢杆菌.

难辨梭状芽孢杆菌主要分泌毒素A和毒素B, 但究竟哪种毒素起主要致病作用在学术界一直存在争议. Kuehne等[11]通过等位基因敲除模型研究发现毒素A、毒素B可在单独或同时作用下导致感染. 但Steele等[12]发现抗毒素B单克隆抗体联合或不联合应用抗病毒A单克隆抗体对CDI患者的治疗效果均较单纯抗毒素A单克隆抗体好, 同时单纯使用抗毒素A单克隆抗体患者死亡率较正常对照组高, 进而认为毒素B在CDI发病过程中起到更加重要的作用.

毒素A和B具有63%的同源氨基酸, 均具有葡糖转移酶, 毒素黏附在肠黏膜上皮细胞后, 通过受体介导的内吞作用进入细胞并催化葡萄糖残基结合到rho蛋白上, 触发细胞内信号分子调节细胞骨架结构和基因表达[13]. rho蛋白糖基化导致蛋白质合成受阻, 引起细胞坏死, 从而引发一系列炎症反应, 并最终导致临床症状的出现.

IBD患者感染难辨梭状芽孢杆菌后症状各异, 有些可能仅为无症状携带者. 但一般表现为腹泻、腹痛, 粪便多带有恶臭气味, 可见黏液或脓血, 常伴发热、呕吐、脱水等中毒症状[9], 极少数患者还可排出斑块状的伪膜. 严重者还可出现肠梗阻、中毒性巨结肠、穿孔及多器官功能衰竭等并发症, 即使进行积极抗感染乃至手术治疗, 其平均死亡率仍高达67%[14].

结肠镜下, 早期患者肠黏膜可仅有轻度充血和水肿, 严重时可见黏膜脆性增加伴溃疡形成, 表面覆有黄白或黄绿色伪膜. 但伪膜形成在IBD患者中极为少见, 因此有学者推荐内镜检查作为评估疾病活动度及排除腹泻继发因素的方法而不作为常规检查[15].

青霉素类、头孢菌素类、克林霉素、先锋霉素类及喹诺酮类[16]等抗生素均可导致CDI. 其主要通过改变肠道正常菌群分布使难辨梭状芽孢杆菌处于优势增殖地位而致病. 但其在IBD患者中的作用目前为止仍存在争议, Schneeweiss等[17]研究报道57.2%的IBD合并CDI患者在发病前6 mo曾接受过抗生素治疗, 另一项对照研究[18]显示UC患者30 d前使用抗生素可使CDI风险增加12倍. 但也有相关学者[19]反对此观点.

长期住院或近期手术是另一危险因素, Kariv等[18]研究报道在长期住院及近期手术同时存在的情况下, IBD患者CDI风险是正常对照组的3.67倍.

IBD本身可能就是CDI的危险因素, Rodemann等[20]研究报道IBD患者CDI的风险是非IBD患者的3倍, 另一研究[7]发现IBD患者CDI的发生率较正常成人明显升高并且在UC患者中更为常见. 但IBD患者应用免疫抑制剂或激素等药物治疗可能导致感染风险增加, Issa等[21]研究发现2004、2005年分别有64%、78%存在CDI的IBD患者行免疫抑制剂维持治疗. Schneeweiss等[17]报道IBD患者最初开始应用糖皮质激素和/或免疫抑制剂, 其CDI的风险是单纯应用免疫抑制剂的3倍, 同时发现应用生物制剂对IBD患者无感染风险. 另一项研究[22]建议限制IBD患者使用糖皮质激素, 从而减少CDI及由此而造成的死亡.

最新研究发现, 抑酸剂, 主要包括质子泵抑制剂(proton pump inhibitors, PPI)及H2受体阻滞剂, 也可诱发CDI. Deshpande等[23]发现PPI可增加IBD患者CDI的风险, 但同年发表在PLoS One的meta分析[24]却反对此观点, 认为PPI与CDI之间无明显的因果关系. Tleyjeh等[25]研究报道应用H2受体阻滞剂2 wk即可增加发生CDI的风险, 尤其是同时使用抗生素的患者. 其机制可能与难辨梭状芽孢杆菌繁殖体(正常情况可被胃酸杀死)因使用了抑酸剂而存活, 进而导致感染. 因此, 减少抑酸剂的不适当使用可能会显著降低CDI发生率.

由于症状的重叠性, IBD合并CDI与单纯的IBD急性发作往往难以分清[26]. 在血液化验方面, 两者均可表现为血白细胞增多、低蛋白血症及粪便的白细胞增多等[27]. 为配合治疗, 临床上需要快速而准确地检测. 目前检测方法主要包括粪便培养、细胞毒素中和试验(cell cytotoxicity neutralization assay, CCNA)、酶联免疫测定(enzyme immunoassays, EIA)、核苷酸扩增试验(nucleic acid amplification tests, NAATs)技术等. 粪便培养是既往诊断CDI的金标准, 可辨别细菌的分子型, 虽然敏感性高, 但耗时长且特异性低, 不能区分产毒株和非产毒株, 且需进一步行毒素检测, 可用于分子流行病学和药敏试验, 但不推荐作为临床常规应用[28].

CCNA敏感性较高但特异性低, 对技术要求高, 仅能检测毒素B, 其阴性并不能排除感染, 且要48-72 h才能得到结果, 故其临床应用受到了一定限制.

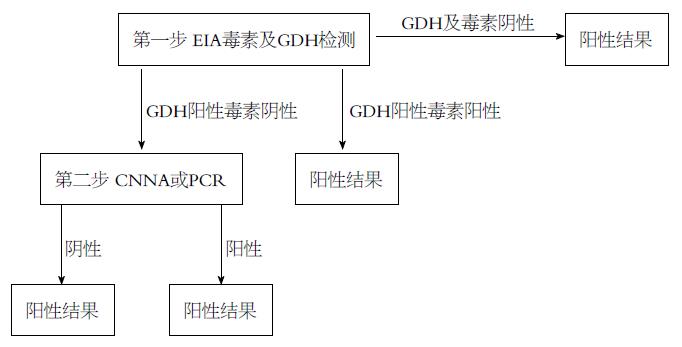

EIA可检测毒素A和毒素B, 价格相对便宜, 且2-6 h即可出结果, 敏感性高而特异性较低. Deshpande等[29]报道使用EIA分析粪便样本其首次检出率为81%, 重复两次可继续检出14%及5%的样本. 同时EIA还可以检测谷氨酸脱氢酶(glutamine dehydrogenase, GDH), 其阴性预测值较高, 是较为理想的筛选方法[30], 但因其不能区分产毒株和非产毒株仍需进一步行EIA毒素检测或PCR检测. 联合应用EIA毒素及GDH检测可提高特异性[31].

NAATs中应用较多的是聚合酶链反应(polymerase chain reaction, PCR)技术, 是目前检测CDI最灵敏的方法, 其敏感性高达90%以上, 且特异性高, 具有快速高效的优点[28]. 但其价格昂贵, 且能发现隐性感染者, 需结合临床症状决定是否对感染者进行治疗. 即便如此, 因该方法的优越性, 近年来已有逐渐取代粪便培养、CNNA及EIA法的趋势[31-33], 可能成为检测CDI的新金标准.

目前部分实验室多采用两步法检测CDI[34], 检测方法囊括了EIA、CCNA以及PCR. 联合检测可以获得75%-100%的敏感性及极高的特异性[35], 具体步骤如图1所示.

立即停止有可能造成CDI的抗生素是治疗最重要的一步, 若无法停止抗生素使用, 可选择其他不易造成CDI的药物. 同时予以必要的对症支持治疗, 如止泻、纠正水、电解质紊乱及低蛋白血症等. 但对于是否应该停止IBD患者免疫抑制剂或激素的应用目前仍然存在争议, 一项回顾性研究[36]报道继续使用免疫抑制剂的患者较对照组并发症多、死亡率高.

甲硝唑及万古霉素是目前治疗的首选用药. 甲硝唑可以采用口服或静脉注射, 一般情况下首选口服给药, 而使用万古霉素时需采取口服或灌肠[37]. Nelson等[38]研究显示对于轻中度患者, 万古霉素与甲硝唑疗效相当, 因此推荐轻中度患者口服甲硝唑治疗(250 mg/6 h或500 mg/8 h, 10-14 d). 但随着近年来甲硝唑耐药率的增加, 对于病情危重的患者[39], 建议口服万古霉素治疗(125 mg/6 h, 14 d). 而对于存在肠梗阻或中毒性巨结肠等并发症的患者, 建议予以万古霉素经鼻胃管[40](500 mg/6 h)或灌肠给药[41](500 mg/6 h)以提高患处的血药浓度或静脉应用甲硝唑治疗[42](500 mg/8 h), 对于初次复发的患者[43], 亦可采用以上方法.

但对多次复发的患者[39], 需采用万古霉素冲击给药(125 mg/6 h, 10-14 d; 125 mg/12 h, 1 wk; 125 mg/d, 1 wk; 125 mg/2 d, 2-8 wk).

其他抗生素[44-48]如杆菌肽、替考拉宁、夫西地酸、硝唑沙奈、利福平、利福昔明及非达米星等也开始应用于CDI的治疗, 但效果尚未得到大规模研究的证实.

Lowy等[49]报道人类单克隆抗体和万古霉素或甲硝唑联合使用, 可以减少毒素A、B, 降低CDI的复发率. 最新研究[12]发现含有抗毒素B单克隆抗体较单纯抗毒素A单克隆抗体疗效好, 并且可明显降低死亡率. 另有研究[50]使用静脉免疫球蛋白治疗严重的CDI, 发现仅对部分患者有效, 故还需要进一步的研究确定其疗效及安全性.

生态治疗包括益生菌及粪菌移植(fecal microbiota transplantation, FMT)治疗.

益生菌有助于恢复肠道菌群, 利于CDI的治疗. Na等[51]报道鲍氏酵母菌及乳酸杆菌可减少高危患者发生CDI, 另一研究[52]发现鲍氏酵母菌联合万古霉素或甲硝唑治疗, 对预防复发有一定作用, 而乳酸杆菌则无效, 但目前暂无单独使用益生菌治疗CDI有效的报道.

FMT是指将健康人粪便中的功能菌群, 移植到患者胃肠道内, 重建具有正常功能的肠道菌群, 实现肠道及肠道外疾病的诊疗. 近年来已有相当多的学者将其应用于CDI患者且都获得较好的疗效. Hamilton等[53]用标准冻存粪菌治疗43例CDI患者, 总成功率为95%, 且进一步通过16rRNA基因测序方法[54]证实了其可以重建肠道菌群及清除难辨梭状芽孢杆菌. 随后, 一个多中心研究[55]报道FMT治疗CDI总治愈率高达98%, 其中, 91%的患者通过一次移植即治愈. 同时, Brandt等[56]认为FMT治疗严重CDI可尽量避免手术及死亡发生. 尽管FMT可能导致疾病的传播、标准操作流程尚未统一, 且其长期疗效尚未得到相关对照研究的证实, 但目前国内外学者已将其作为经药物治疗无效及反复发作的IBD患者的挽救治疗[57].

CDI在IBD患者中的地位逐渐被认识, 但其发病机制仍未完全明确. 长期使用抗生素、免疫抑制剂、抑酸剂的患者发生CDI的可能性明显增加. 目前推荐结合多种方法检测以提高敏感性及特异性. 选择有效抗生素治疗是一重点, 同时可辅以免疫及生态治疗. FMT目前已临床应用于IBD及CDI患者, 但其长期疗效仍待考证. IBD危害性大, 可出现多种并发症, 应注意预防CDI的发生, 从而改善患者预后.

近年来研究发现微生物因素在炎症性肠病起病中起到了不可忽视的作用, 同时难辨梭状芽孢杆菌感染(Clostridium difficile infection, CDI)在成人及儿童炎症性肠病(inflammatory bowel disease, IBD)患者中的发生率不断上升. 因此需要正确的认识两者之间的关系.

季国忠, 教授, 南京医科大学第二附属医院消化科

近一年来越来越多的文章报道粪菌移植可以用来治疗CDI, 有多项研究报道其有效性, 但尚未得到大规模前瞻性研究的证实.

Hamilton等用标准冻存粪菌治疗CDI患者, 总成功率为95%, 且进一步证实了其可以重建肠道菌群及清除难辨梭状芽孢杆菌. 另有研究报道其总体治愈率高达98%.

本文概述了难辨梭状芽孢杆菌在炎症性肠病中的进展, 包括最近报道的危险因素、新型的检测方法, 以及免疫及生态治疗在炎症性肠病合并CDI中的应用.

本文对于临床上炎症性肠病合并CDI的患者的诊治具有一定的指导意义, 可以帮助识别CDI及时治疗, 改善患者预后.

本文综述了难辨梭状芽孢杆菌在炎症性肠病中的研究进展, 选题新颖, 内容详实全面, 归纳炎症性肠病合并难辨梭状芽孢杆菌感染的诊治进展, 有一定的临床指导价值.

编辑: 田滢 电编: 鲁亚静

| 1. | Bossuyt P, Verhaegen J, Van Assche G, Rutgeerts P, Vermeire S. Increasing incidence of Clostridium difficile-associated diarrhea in inflammatory bowel disease. J Crohns Colitis. 2009;3:4-7. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 2. | Pant C, Anderson MP, Deshpande A, Altaf MA, Grunow JE, Atreja A, Sferra TJ. Health care burden of Clostridium difficile infection in hospitalized children with inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2013;19:1080-1085. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 3. | Kelly CP, LaMont JT. Clostridium difficile--more difficult than ever. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:1932-1940. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 4. | McDonald LC, Owings M, Jernigan DB. Clostridium difficile infection in patients discharged from US short-stay hospitals, 1996-2003. Emerg Infect Dis. 2006;12:409-415. [PubMed] |

| 5. | Pépin J, Valiquette L, Alary ME, Villemure P, Pelletier A, Forget K, Pépin K, Chouinard D. Clostridium difficile-associated diarrhea in a region of Quebec from 1991 to 2003: a changing pattern of disease severity. CMAJ. 2004;171:466-472. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Freeman J, Bauer MP, Baines SD, Corver J, Fawley WN, Goorhuis B, Kuijper EJ, Wilcox MH. The changing epidemiology of Clostridium difficile infections. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2010;23:529-549. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 7. | Clayton EM, Rea MC, Shanahan F, Quigley EM, Kiely B, Hill C, Ross RP. The vexed relationship between Clostridium difficile and inflammatory bowel disease: an assessment of carriage in an outpatient setting among patients in remission. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104:1162-1169. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 8. | Rupnik M, Wilcox MH, Gerding DN. Clostridium difficile infection: new developments in epidemiology and pathogenesis. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2009;7:526-536. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 9. | Navaneethan U, Venkatesh PG, Shen B. Clostridium difficile infection and inflammatory bowel disease: understanding the evolving relationship. World J Gastroenterol. 2010;16:4892-4904. [PubMed] |

| 10. | Qin J, Li R, Raes J, Arumugam M, Burgdorf KS, Manichanh C, Nielsen T, Pons N, Levenez F, Yamada T. A human gut microbial gene catalogue established by metagenomic sequencing. Nature. 2010;464:59-65. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 11. | Kuehne SA, Cartman ST, Heap JT, Kelly ML, Cockayne A, Minton NP. The role of toxin A and toxin B in Clostridium difficile infection. Nature. 2010;467:711-713. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 12. | Steele J, Mukherjee J, Parry N, Tzipori S. Antibody against TcdB, but not TcdA, prevents development of gastrointestinal and systemic Clostridium difficile disease. J Infect Dis. 2013;207:323-330. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 13. | Voth DE, Ballard JD. Clostridium difficile toxins: mechanism of action and role in disease. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2005;18:247-263. [PubMed] |

| 14. | Chan S, Kelly M, Helme S, Gossage J, Modarai B, Forshaw M. Outcomes following colectomy for Clostridium difficile colitis. Int J Surg. 2009;7:78-81. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 15. | Ananthakrishnan AN, Issa M, Binion DG. Clostridium difficile and inflammatory bowel disease. Med Clin North Am. 2010;94:135-153. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 16. | Kelly CP. A 76-year-old man with recurrent Clostridium difficile-associated diarrhea: review of C. difficile infection. JAMA. 2009;301:954-962. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 17. | Schneeweiss S, Korzenik J, Solomon DH, Canning C, Lee J, Bressler B. Infliximab and other immunomodulating drugs in patients with inflammatory bowel disease and the risk of serious bacterial infections. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2009;30:253-264. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 18. | Kariv R, Navaneethan U, Venkatesh PG, Lopez R, Shen B. Impact of Clostridium difficile infection in patients with ulcerative colitis. J Crohns Colitis. 2011;5:34-40. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 19. | Kelsen JR, Kim J, Latta D, Smathers S, McGowan KL, Zaoutis T, Mamula P, Baldassano RN. Recurrence rate of clostridium difficile infection in hospitalized pediatric patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2011;17:50-55. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 20. | Rodemann JF, Dubberke ER, Reske KA, Seo da H, Stone CD. Incidence of Clostridium difficile infection in inflammatory bowel disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;5:339-344. [PubMed] |

| 21. | Issa M, Vijayapal A, Graham MB, Beaulieu DB, Otterson MF, Lundeen S, Skaros S, Weber LR, Komorowski RA, Knox JF. Impact of Clostridium difficile on inflammatory bowel disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;5:345-351. [PubMed] |

| 22. | Das R, Feuerstadt P, Brandt LJ. Glucocorticoids are associated with increased risk of short-term mortality in hospitalized patients with clostridium difficile-associated disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010;105:2040-2049. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 23. | Deshpande A, Pant C, Pasupuleti V, Rolston DD, Jain A, Deshpande N, Thota P, Sferra TJ, Hernandez AV. Association between proton pump inhibitor therapy and Clostridium difficile infection in a meta-analysis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;10:225-233. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 24. | Tleyjeh IM, Bin Abdulhak AA, Riaz M, Alasmari FA, Garbati MA, AlGhamdi M, Khan AR, Al Tannir M, Erwin PJ, Ibrahim T. Association between proton pump inhibitor therapy and clostridium difficile infection: a contemporary systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2012;7:e50836. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 25. | Tleyjeh IM, Abdulhak AB, Riaz M, Garbati MA, Al-Tannir M, Alasmari FA, Alghamdi M, Khan AR, Erwin PJ, Sutton AJ. The association between histamine 2 receptor antagonist use and Clostridium difficile infection: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2013;8:e56498. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 26. | Ben-Horin S, Margalit M, Bossuyt P, Maul J, Shapira Y, Bojic D, Chermesh I, Al-Rifai A, Schoepfer A, Bosani M. Prevalence and clinical impact of endoscopic pseudomembranes in patients with inflammatory bowel disease and Clostridium difficile infection. J Crohns Colitis. 2010;4:194-198. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 27. | Issa M, Ananthakrishnan AN, Binion DG. Clostridium difficile and inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2008;14:1432-1442. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 28. | Kufelnicka AM, Kirn TJ. Effective utilization of evolving methods for the laboratory diagnosis of Clostridium difficile infection. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;52:1451-1457. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 29. | Deshpande A, Pasupuleti V, Patel P, Pant C, Pagadala M, Hall G, Hu B, Jain A, Rolston DD, Sferra TJ. Repeat stool testing for Clostridium difficile using enzyme immunoassay in patients with inflammatory bowel disease increases diagnostic yield. Curr Med Res Opin. 2012;28:1553-1560. [PubMed] |

| 30. | Snell H, Ramos M, Longo S, John M, Hussain Z. Performance of the TechLab C. DIFF CHEK-60 enzyme immunoassay (EIA) in combination with the C. difficile Tox A/B II EIA kit, the Triage C. difficile panel immunoassay, and a cytotoxin assay for diagnosis of Clostridium difficile-associated diarrhea. J Clin Microbiol. 2004;42:4863-4865. [PubMed] |

| 31. | Sharp SE, Ruden LO, Pohl JC, Hatcher PA, Jayne LM, Ivie WM. Evaluation of the C.Diff Quik Chek Complete Assay, a new glutamate dehydrogenase and A/B toxin combination lateral flow assay for use in rapid, simple diagnosis of clostridium difficile disease. J Clin Microbiol. 2010;48:2082-2086. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 32. | Stamper PD, Alcabasa R, Aird D, Babiker W, Wehrlin J, Ikpeama I, Carroll KC. Comparison of a commercial real-time PCR assay for tcdB detection to a cell culture cytotoxicity assay and toxigenic culture for direct detection of toxin-producing Clostridium difficile in clinical samples. J Clin Microbiol. 2009;47:373-378. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 33. | Eastwood K, Else P, Charlett A, Wilcox M. Comparison of nine commercially available Clostridium difficile toxin detection assays, a real-time PCR assay for C. difficile tcdB, and a glutamate dehydrogenase detection assay to cytotoxin testing and cytotoxigenic culture methods. J Clin Microbiol. 2009;47:3211-3217. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 34. | Kvach EJ, Ferguson D, Riska PF, Landry ML. Comparison of BD GeneOhm Cdiff real-time PCR assay with a two-step algorithm and a toxin A/B enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay for diagnosis of toxigenic Clostridium difficile infection. J Clin Microbiol. 2010;48:109-114. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 35. | Novak-Weekley SM, Marlowe EM, Miller JM, Cumpio J, Nomura JH, Vance PH, Weissfeld A. Clostridium difficile testing in the clinical laboratory by use of multiple testing algorithms. J Clin Microbiol. 2010;48:889-893. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 36. | Ben-Horin S, Margalit M, Bossuyt P, Maul J, Shapira Y, Bojic D, Chermesh I, Al-Rifai A, Schoepfer A, Bosani M. Combination immunomodulator and antibiotic treatment in patients with inflammatory bowel disease and clostridium difficile infection. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;7:981-987. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 37. | Leffler DA, Lamont JT. Treatment of Clostridium difficile-associated disease. Gastroenterology. 2009;136:1899-1912. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 38. | Nelson RL, Kelsey P, Leeman H, Meardon N, Patel H, Paul K, Rees R, Taylor B, Wood E, Malakun R. Antibiotic treatment for Clostridium difficile-associated diarrhea in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;CD004610. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 39. | Cohen SH, Gerding DN, Johnson S, Kelly CP, Loo VG, McDonald LC, Pepin J, Wilcox MH. Clinical practice guidelines for Clostridium difficile infection in adults: 2010 update by the society for healthcare epidemiology of America (SHEA) and the infectious diseases society of America (IDSA). Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2010;31:431-455. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 40. | Fekety R, Silva J, Kauffman C, Buggy B, Deery HG. Treatment of antibiotic-associated Clostridium difficile colitis with oral vancomycin: comparison of two dosage regimens. Am J Med. 1989;86:15-19. [PubMed] |

| 41. | Apisarnthanarak A, Razavi B, Mundy LM. Adjunctive intracolonic vancomycin for severe Clostridium difficile colitis: case series and review of the literature. Clin Infect Dis. 2002;35:690-696. [PubMed] |

| 42. | Friedenberg F, Fernandez A, Kaul V, Niami P, Levine GM. Intravenous metronidazole for the treatment of Clostridium difficile colitis. Dis Colon Rectum. 2001;44:1176-1180. [PubMed] |

| 43. | Pépin J, Routhier S, Gagnon S, Brazeau I. Management and outcomes of a first recurrence of Clostridium difficile-associated disease in Quebec, Canada. Clin Infect Dis. 2006;42:758-764. [PubMed] |

| 44. | Garey KW, Ghantoji SS, Shah DN, Habib M, Arora V, Jiang ZD, DuPont HL. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled pilot study to assess the ability of rifaximin to prevent recurrent diarrhoea in patients with Clostridium difficile infection. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2011;66:2850-2855. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 45. | Mullane KM, Miller MA, Weiss K, Lentnek A, Golan Y, Sears PS, Shue YK, Louie TJ, Gorbach SL. Efficacy of fidaxomicin versus vancomycin as therapy for Clostridium difficile infection in individuals taking concomitant antibiotics for other concurrent infections. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;53:440-447. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 46. | Louie TJ, Miller MA, Mullane KM, Weiss K, Lentnek A, Golan Y, Gorbach S, Sears P, Shue YK. Fidaxomicin versus vancomycin for Clostridium difficile infection. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:422-431. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 47. | Musher DM, Logan N, Bressler AM, Johnson DP, Rossignol JF. Nitazoxanide versus vancomycin in Clostridium difficile infection: a randomized, double-blind study. Clin Infect Dis. 2009;48:e41-e46. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 48. | Lagrotteria D, Holmes S, Smieja M, Smaill F, Lee C. Prospective, randomized inpatient study of oral metronidazole versus oral metronidazole and rifampin for treatment of primary episode of Clostridium difficile-associated diarrhea. Clin Infect Dis. 2006;43:547-552. [PubMed] |

| 49. | Lowy I, Molrine DC, Leav BA, Blair BM, Baxter R, Gerding DN, Nichol G, Thomas WD, Leney M, Sloan S. Treatment with monoclonal antibodies against Clostridium difficile toxins. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:197-205. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 50. | Abougergi MS, Broor A, Cui W, Jaar BG. Intravenous immunoglobulin for the treatment of severe Clostridium difficile colitis: an observational study and review of the literature. J Hosp Med. 2010;5:E1-E9. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 51. | Na X, Kelly C. Probiotics in clostridium difficile Infection. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2011;45 Suppl:S154-S158. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 52. | Pillai A, Nelson R. Probiotics for treatment of Clostridium difficile-associated colitis in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008;CD004611. [PubMed] |

| 53. | Hamilton MJ, Weingarden AR, Sadowsky MJ, Khoruts A. Standardized frozen preparation for transplantation of fecal microbiota for recurrent Clostridium difficile infection. Am J Gastroenterol. 2012;107:761-767. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 54. | Hamilton MJ, Weingarden AR, Unno T, Khoruts A, Sadowsky MJ. High-throughput DNA sequence analysis reveals stable engraftment of gut microbiota following transplantation of previously frozen fecal bacteria. Gut Microbes. 2013;4:125-135. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 55. | Brandt LJ, Aroniadis OC, Mellow M, Kanatzar A, Kelly C, Park T, Stollman N, Rohlke F, Surawicz C. Long-term follow-up of colonoscopic fecal microbiota transplant for recurrent Clostridium difficile infection. Am J Gastroenterol. 2012;107:1079-1087. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 56. | Brandt LJ, Borody TJ, Campbell J. Endoscopic fecal microbiota transplantation: "first-line" treatment for severe clostridium difficile infection? J Clin Gastroenterol. 2011;45:655-657. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 57. | Anderson JL, Edney RJ, Whelan K. Systematic review: faecal microbiota transplantation in the management of inflammatory bowel disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2012;36:503-516. [PubMed] [DOI] |