Abstract

The rise of Chinese ‘state capitalism’ such as expressed by the global expansion of Chinese state-owned enterprises (SOEs) has been met with substantial suspicion on the part of the Western corporate and political establishment—including among Washington’s policy-making elite. The underpinning claim that the rise of SOEs would impair market mechanisms, we argue, is, however, theoretically problematic and empirically incorrect. Taking the example of the global oil and gas sector, the article illustrates that at firm level major corporations from rising powers, such as China, increasingly cooperate with Western firms, including with American oil majors. In that sense, Chinese firms participate in capitalist competition just as any Western firm. The roots of the assumed threat posed by China’s rise, we argue, must rather be situated in the distinctive nature of the state-capital nexus in the USA and China, respectively, and the configuration of elite networks underpinning this nexus. We will illustrate this by analysing the social networks in which directors of major Chinese and US oil firms are embedded, including the networks of corporate ties, affiliations with (transnational) policy planning bodies and state-business ties.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

16 Chinese NOC directors (with six of them having overlapping directorships between CNPC and PetroChina) and 24 American IOC directors.

We do not incorporate affiliations with subsidiaries as separate entities in these analyses because it is inter-firm and not intra-firm relations that we are primarily interested in here.

Only a handful are based in Switzerland (3), France (1), Jersey (1), Germany (1) and finally Mexico (1).

Except Lui Hongru who has one corporate affiliation to a transnational US-based financial firm Greater China Securities and its subsidiary Etech Securities, and Chen Zhiwu who has a corporate affiliation with UK-based global investment management firm the Permal Group.

While Houston Endowment Inc is a foundation and thus not a corporation, it does invest substantively in real estate and board membership of this organization can therefore appropriately be seen as a corporate affiliation.

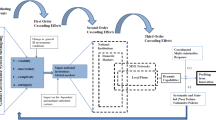

The individual policy planning affiliations are shown in the graph without a label in order to give an impression of the numbers while retaining readability of the figure.

Although the OECD is an international organization and thus not a private planning body, it is certainly a key policy planning institute, especially since key corporate directors are involved as advisers and members for this institute forming a crucial link to policy making. We have therefore included it here.

Jiang Jiemin was removed as SASAC Chairman in 2013 on the basis of charges of corruption and has been expelled from the CPC in 2014.

After 2012, of course, Exxon Mobil's longtime CEO Rex Tillerson has been appointed US Secretary of State in the Trump administration.

Although our findings elicit the need for a more systematic and in-depth analysis comparing different forms of state capitalism—or state-led development—both in the West and in Asia more broadly (see e.g. McNally 2012), this falls outside the scope of the present article which is primarily concerned with an empirical analysis of the impact of transnationalizing Chinese SOEs on US elite power structures.

Telephone interview, Xiaojie Xu, CNPC consultant and former director overseas investments, 21 January 2010. Email interview, CNPC’s Director Petroleum Market Study, 14 June 2011. Interview, Professor Weihan Wang, 26 February 2010, Houston, USA.

Ibid.

A development that is also indicated by CNPC’s (and other Chinese NOCs) current organizational structure with PetroChina as a listed private entity within the state-owned CNPC.

References

Andrews-Speed, Philip, and Ronald Dannreuther. 2011. China, oil and global politics. London: Routledge.

Bijian, Zheng. 2005. China’s peaceful rise to great-power status. Foreign Affairs 84 (5): 18.

Bremmer, Ian. 2008. The return of state capitalism. Survival 50 (3): 55–64.

Bremmer, Ian. 2009. State capitalism comes of age. The end of the free market? Foreign Affairs 88 (3): 40–56.

Breslin, Shaun. 2013. China and the global order: Signalling threat or friendship? International Affairs 89 (3): 615–634.

Borgatti, Stephen P., Martin G. Everett, and Linton V. Freeman. 2002. Ucinet for windows: Software for social network analysis. Harvard, MA: Analytic Technologies.

Carroll, William K. 2010. The making of a transnational capitalist class: Corporate power in the 21st century. London and New York: Zed Books.

Carroll, William K., and Meindert Fennema. 2002. Is there a transnational business community? International Sociology 17 (3): 393–419.

Carroll, William K., and Colin Carson. 2003. The network of global corporations and elite policy groups: A structure for transnational capitalist class formation? Global Networks 3 (1): 29–57.

De Graaff, Nana. 2011. A global energy network? The expansion and integration of non-triad national oil companies. Global Networks 11 (2): 262–283.

De Graaff, Nana. 2013. Towards a hybrid global energy order. State-owned oil companies, corporate elite networks and governance. unpublished manuscript, PhD diss., Faculty of Social Sciences, VU University, Amsterdam.

De Graaff, Nana. 2014. Global networks and the two faces of Chinese national oil companies. Perspectives on Global Development and Technology 13 (5–6): 539–563.

Domhoff, William G. 1967. Who rules America?. Englewood Cliffs, N.J: Prentice Hall.

Domhoff, William G. 2009. Who rules America? Challenges to corporate and class dominance. New York: McGraw-Hill.

Downs, Erica. 2007a. The fact and fiction of Sino–African energy relations. China Security 3 (2): 42–69.

Downs, Erica. 2007b. China’s quest for overseas oil. Far Eastern Economic Review 170 (7): 52–56.

Downs, Erica. 2008. Business interest groups in Chinese politics: The case of the oil companies. In China’s changing political landscape. Prospects for democracy, ed. L. Cheng, 121–141. Washington: The Brookings Institution.

Energy Intelligence Group. 2013. Petroleum intelligence weekly, PIW Top 50. November 2013, p. 2.

Heemskerk, Eelke M. 2013. The rise of the European corporate elite: Evidence from the network of interlocking directorates in 2005 and 2010. Economy and Society 42 (1): 74–101.

Holslag, Jonathan. 2006. China’s new mercantilism in central Africa. African and Asian Studies 5 (2): 133–169.

Ikenberry, G.John. 2008. The rise of China: Power, institutions and the western order. In China’s ascent: Power, security, and the future of international politics, ed. Robert S. Ross, and Zhu Feng. Ithaca, N.Y.: Cornell University Press.

Kagan, Robert. 2006. League of dictators? The Washington Post, April 30.

Kahler, Miles. 2013. Rising powers and global governance: Negotiating change in a resilient status quo. International Affairs 89 (3): 711–729.

Kong, Bo. 2010. China’s international petroleum policy. Santa Barbara: Greenwood Publishing Group.

Mearsheimer, John. 2010. The gathering storm: China’s challenge to US power in Asia. The Chinese Journal of International Politics 3: 381–396. doi:10.1093/cjip/poq016.

McNally, Christopher A. 2012. Sino-capitalism. China’s re-emergence and the international political economy. World Politics 64: 741–766. doi:10.1017/S0043887112000202.

Nölke, Andreas, Tobias ten Brink, Simone Claar, and Christian May. 2015. Domestic structures, foreign economic policies and global economic order: Implications from the rise of large emerging economies. European Journal of International Relations 21 (3): 538–567.

Rachman, Gideon. 2008. Illiberal capitalism: Russia and China chart their own course. Financial Times, January 8.

Rachman, Gideon. 2012. The end of the win–win world. Why China’s rise is bad for the US—and other dark forces. Foreign Policy. http://www.foreignpolicy.com/articles/2012/01/24/the_end_of_the_win_win_world.

Scott, John, and Peter J. Carrington (eds.). 2011. The Sage handbook of social network analysis. London: Sage.

Shambaugh, David. 2013. China goes global. The Partial Power. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press.

Stephens, Philip. 2013. China has thrown down a gauntlet to America. Financial Times, Comment, November 28.

Stephen, Matthew D. 2014. Rising powers, global capitalism and liberal global governance: A historical materialist account of the BRICs challenge. European Journal of International Relations 20 (4): 912–938.

Ten Brink, Tobias. 2013. Paradoxes of prosperity in China’s new capitalism. Journal of Current Chinese Affairs 42 (3): 17–44.

The Economist. 2014. Catching the Eagle. August 22. http://www.economist.com/blogs/graphicdetail/2014/08/chinese-and-american-gdp-forecasts.

The Economist. 2012a. New masters of the universe. How state enterprise is spreading. Special Report: State Capitalism.

The Economist. 2012b. The visible hand. Special Report: State Capitalism.

Van Apeldoorn, Bastiaan. 2002. Transnational capitalism and the struggle over European integration. London and New York: Routledge.

Van Apeldoorn, Bastiaan, Naná de Graaff, and Henk Overbeek. 2012. The Reconfiguration of the global state-capital Nexus. Globalizations 9 (4): 471–486.

Van Apeldoorn, Bastiaan, and Nana De Graaff. 2014. Corporate elite networks and US post-cold war grand strategy from Clinton to Obama. European Journal of International Relations 20 (1): 29–55.

Van Apeldoorn, Bastiaan, and Naná de Graaff. 2016. American grand strategy and corporate elite networks. The open door and its variations since the end of the cold war. London and New York: Routledge.

Yong, Wang, and Louis Pauly. 2013. Chinese IPE debates on (American) hegemony. Review of International Political Economy 20 (6): 1165–1188.

Zweig, David, and Bi Jianhai. 2005. China’s global hunt for energy. Foreign Affairs 84 (5): 23–38.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

de Graaff, N., van Apeldoorn, B. US elite power and the rise of ‘statist’ Chinese elites in global markets. Int Polit 54, 338–355 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41311-017-0031-2

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41311-017-0031-2