Abstract

It is common wisdom in political communication research that the media matter for democratic processes and citizens' political attitudes. However, we have only limited knowledge about the role of the media in understanding support for European integration and virtually no knowledge about their role in relation to the emergence and consolidation of Euroscepticism. Drawing on experimental data and evidence from panel surveys in two countries, this article demonstrates how news media, by framing Euro-politics as an arena for strategically operating, self-serving politicians, can fuel public cynicism and scepticism. However, this effect is conditional upon the level of strategic news framing and in a situation with limited strategically framed news about the European Union, exposure to news reverses this process and reduces public cynicism. The article demonstrates that a spiral of media-driven Euroscepticism is neither true for all media nor for all individuals.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Parts of the results reported here have been published in Communication Science journals (De Vreese, 2004, 2005) with a specific focus on communication theory and with limited attention to the ‘European’ perspective and implications.

The design does not include a control group that would have to be treated to a ‘frameless’ news story, see Iyengar (1991) and Valentino et al. (2001a) for a similar procedure. As this study is designed to test the effects of strategic news, the other group (exposed to issue-driven news) may effectively be considered the functional equivalent of a control group (Brown and Melamed, 1990). For additional details about the experiment, see De Vreese (2004).

Two items in the posttest questionnaire confirmed that participants in the strategy condition felt they had learned more about strategies than issues, and participants in the other condition reported they had learned more about issues than strategies.

Denmark, the host country, was chosen because EU summits have the potential to generate less unfavourable news in the country that hosts the summit (see de Vreese, 2002). The Netherlands was chosen as the comparison because we know that the news volume and tone is affected by EU summits in this country (Semetko and Valkenburg, 2000). This reduces the chances that the findings are idiosyncratic to the Danish case.

The fieldwork dates were: Denmark, wave I 21–28 November 2002; wave II 14–18 December 2002 and the Netherlands, wave I 19–26 November 2002; wave II 17–21 December 2002.

The response rates were: Denmark 77.9% (wave I), 82.8% (wave 2), net sample of 1,288 respondents participating in both waves; The Netherlands 70.9% (wave I), 63.3% (wave II), net sample of 2,136 respondents participating in both waves (see De Vreese, 2005 for additional information about the sampling). In Denmark, the questionnaire was a postal self-administered paper and pencil questionnaire. In the Netherlands, the questionnaire was Web-administrated. These two modes of data collection enable a similar lay-out of the questionnaire and can thus better be compared (Dillman, 2000).

Cynicism has been defined as oppositional to political efficacy (e.g., Acock and Clarke, 1990; Craig et al., 1990; Niemi et al., 1991) and as inversely related to trust in different social, economic, and political institutions (Mishler and Rose, 2001).

The current study extends the work by Cappella and Jamieson (1997) and therefore utilizes the items used in their study worded slightly differently to apply to a policy debate rather than a specific election campaign.

The questions, measured on five-point agree–disagree statements, were: (1) the discussion about the EU enlargement is about what is best for Europe, (2) the politicians are too superficial in their argumentation about the enlargement, (3) the discussion about the enlargement gives me sufficient information to form an opinion, and (4) the discussion about the enlargement is more about political strategies than content.

In the Dutch case, the third item was dropped due to low inter-item correlation.

We include attention given the potential inaccuracy of relying solely on exposure measures (Chaffee and Schleuder, 1986). However, using the simple exposure measure (without the attention to EU news measure) does not substantively alter the findings.

A greater diversity in terms of the news media content on the relevant indicators favours using our detailed exposure measure to each of the different outlets, but given the similarity we use an additive index.

Respondents' reported level of completed education was recoded due to differences in the educational systems, see Appendix.

The content analysis was conducted from 25 November to 16 December 2002.

Public outlets: DR TV-Avisen (9 pm) in Denmark and NOS Journaal (8 pm) in the Netherlands. Commercial outlets: TV2 Nyhederne (7 pm) in Denmark and RTL Nieuws (7.30 pm) in the Netherlands. We acknowledge the dual funding of Danish TV2.

The entire news bulletin was coded. This included 554 stories from TV-Avisen, 458 stories from TV2 Nyhederne, 220 stories from NOS Journaal, and 245 stories from RTL Nieuws.

The papers were Politiken, JyllandsPosten, Berlingske Tidende, BT, and EkstraBladet in Demark, all published Monday to Sunday and in the Netherlands de Volkskrant, Telegraaf, NRC Handelsblad, Algemeen Dagblad, and Trouw, all published Monday to Saturday.

The entire front-page of each newspaper was coded. If stories commenced on the front-page and continued inside the newspaper, these stories were coded in full. A single headline (with no adjacent story) was not coded. Bullets (a headline and a few short, but full sentences) were included. The following number of articles were coded per newspaper: Politiken 260, JyllandsPosten 224, Berlingske Tidende 223, EkstraBladet 90, BT 89, de Volkskrant 214, NRC 231, AD 186, Telegraaf 135, and Trouw 145. The low number of articles in EkstraBladet and BT is due to the tabloid format of the newspaper and the layout of the front page with one or two stories per day.

The content analysis was completed by two native Dutch speakers and two native Danish speakers (all were MA students at the University of Amsterdam). Coders were trained and supervised frequently. The inter-coder reliability test conducted on a randomly selected sample of 50 news stories showed 94–100% inter-coder agreement for the measures relevant to this study. The inter-coder reliability test was performed in pairs of coders for each language. The reliability test was conducted on 25 Dutch and 25 Danish news stories, randomly selected from the news outlets included in the study.

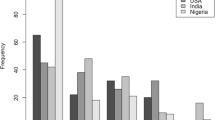

Danish television aired 252 news stories about European affairs during the period of the study. Dutch television news aired 25 stories. Danish newspapers covered EU affairs in 84 front-page articles, whereas Dutch newspapers included 70 articles.

References

Aarts, K. and Semetko, H.A. (2003) ‘The divided electorate: effects of media use on political involvement’, Journal of Politics 65 (3): 759–784.

Acock, A. and Clarke, H.D. (1990) ‘Alternative measures of political efficacy: models and means’, Quality and Quantity 24: 87–105.

Anderson, C.J. (1998) ‘When in doubt use proxies: attitudes to domestic politics and support for the EU’, Comparative Political Studies 31: 569–601.

Anderson, C.J. and Reichert, M.S. (1996) ‘Economic benefits and support for membership in the European Union: a cross-national analysis’, Journal of Public Policy 15: 231–249.

Brown, S.R. and Melamed, L.E. (1990) Experimental Design and Analysis, Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

Cappella, J.N. and Jamieson, K.H. (1997) Spiral of Cynicism. The Press and the Public Good, New York: Oxford University Press.

Chaffee, S.H. and Schleuder, J. (1986) ‘Measurement and effects of attention to media’, Human Communication Research 13: 76–107.

Chaffee, S. and Kanihan, S.F. (1997) ‘Learning about politics from the mass media’, Political Communication 17: 421–430.

Citrin, J. (1974) ‘The political relevance of trust in government’, American Political Science Review 68: 973–988.

Craig, S.C., Niemi, R.G. and Silver, G.E. (1990) ‘Political efficacy and trust: a report on the NES pilot study items’, Political Behavior 12: 289–314.

De Vreese, C.H. (2002) Framing Europe. Television News and European Integration, Amsterdam: Aksant Academic Publishers.

De Vreese, C.H. (2004) ‘The effects of strategic news on political cynicism, issue evaluations and policy support: a two-wave experiment’, Mass Communication and Society 7 (2): 191–215.

De Vreese, C.H. (2005) ‘The spiral of cynicism reconsidered: the mobilizing function of news’, European Journal of Communication 20 (3): 283–301.

De Vreese, C.H. and Boomgaarden, H.G. (2005) ‘Projecting EU referendums. Fear of immigration and support for European integration’, European Union Politics 6 (1): 59–82.

De Vreese, C. and Semetko, H.A. (2002) ‘Cynical and engaged: strategic campaign coverage, public opinion and mobilization in a referendum’, Communication Research 29 (6): 615–641.

De Vreese, C.H. and Semetko, H.A. (2004) Political Campaigning in Referendums: Framing the Referendum Issue, London: Routledge.

Dillman, D.A. (2000) Mail and Internet Surveys: The Tailored Design Method, New York: John Wiley and Sons.

Erber, R. and Lau, R.R. (1990) ‘Political cynicism revisited: an information-processing reconciliation of policy-based and incumbency-based interpretations of changes in trust in government’, American Journal of Political Science Review 34: 236–253.

Eurobarometer (2002) Public Opinion in the European Union, Brussels: European Commission.

Fallows, J. (1996) Breaking the News. How the Media Undermine American Democracy, New York, NY: Pantheon Books.

Farnsworth, S.J. and Lichter, R.S. (2003) The Nightly News Nightmare: Network Television's Coverage of U.S. Presidential Elections, 1988–2000, Lanham, MD: Rowman and Littlefield.

Franklin, M., Marsh, M. and Wlezien, C. (1994) ‘Attitudes toward Europe and referendum votes: a response to Siune and Svensson’, Electoral Studies 13: 117–121.

Gabel, M. (1998) ‘Public support for European integration: an empirical test of five theories’, Journal of Politics 60: 333–354.

Gabel, M. and Palmer, H. (1995) ‘Understanding variation in public support for European integration’, European Journal of Political Research 27: 3–19.

Hewstone, M. (1986) Understanding Attitudes Toward the European Community, New York: Cambridge University Press.

Hibbing, J.R. and Theiss-Morse, E. (1995) Congress as Public Enemy. Public Attitudes Toward American Political Institutions, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Hooghe, L. (2003) ‘Elite versus public opinion on European integration’, European Union Politics 4 (3): 281–304.

Holtz-Bacha, C. (1990) ‘Videomalaise revisited: media exposure and political alienation in West Germany’, European Journal of Communication 5: 73–85.

Inglehart, R. (1970) ‘Cognitive mobilization and European identity’, Comparative Politics 3: 45–70.

Iyengar, S. (1991) Is Anyone Responsible?, Chicago: Chicago University Press.

Jamieson, K.H. (1992) Dirty Politics: Deception, Distraction, and Democracy, New York: Oxford University Press.

Kinder, D.R. and Palfrey, T. (eds.) (1993) Experimental Foundations of Political Science, Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

Klapper, J. (1960) The Effects of Mass Communication, New York: Free Press.

Krouwel, A. and Abts, K. (2007) ‘Varieties of eurosceptism and populist mobilization: transforming attitudes from mild euroscepticism to harsh eurocynicism’, Acta Politica 42 (2/3): 252–270.

Lichter, R. and Noyes, R.E. (1996) Good Intentions Make Bad News: Why Americans Hate Campaign Journalism, Lanham: Rowan and Littlefield.

Marks, G. and Hoooghe, L. (2003) ‘National identity and support for European integration’, Discussion Paper SP IV. Berlin: WZB.

Markus, G.B. (1979) Analyzing Panel Data, Beverly Hills, CA: Sage University Papers.

McLaren, L.M. (2002) ‘Public support for the European Union: cost/benefit analysis or perceived cultural threat?’ Journal of Politics 64: 551–566.

Meyer, C. (1999) ‘Political legitimacy and the invisibility of politics: exploring the European Union's communication deficit’, Journal of Common Market Studies 37: 617–639.

Miller, A.H. (1974) ‘Political issues and trust in government: 1946–1970’, American Political Science Review 68: 951–972.

Mishler, W. and Rose, R. (2001) ‘What are the origins of political trust? Testing institutional and cultural theories in post-communist societies’, Comparative Political Studies 34 (1): 30–62.

Nelson, T.E., Clawson, R.A. and Oxley, Z.M (1997) ‘Media framing of a civil liberties conflict and its effect on tolerance’, American Political Science Review 91: 567–584.

Niemi, R.G., Craig, S.C. and Mattei, F. (1991) ‘Measuring internal political efficacy in the 1988 National Election Study’, American Political Science Review 85: 1407–1413.

Nye Jr, J.S., Zelikow, P.D. and King, D.C. (eds.) (1997) Why People Don’t Trust Government, Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Norris, P. (2000) A Virtuous Circle. Political Communications in Postindustrial Societies, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Patterson, T.E. (1993) Out of Order, New York: Alfred A. Knopf.

Patterson, T.E. (2002) The Vanishing Voter: Public Involvement in an Age of Uncertainty, New York: Alfred A. Knopf.

Perloff, R.M. (2003) ‘Negative messengers. A review essay’, Journal of Communication 53 (4): 729–733.

Peter, J. (2004) ‘Our long ‘Return to the Concept of Powerful Mass Media’— a cross-national comparative investigation of the effects of consonant media coverage’, International Journal of Public Opinion Research 16: 144–168.

Pinkleton, B.E. and Austin, E.W. (2001) ‘Individual motivations, perceived media importance and political disaffection’, Political Communication 18: 321–334.

Price, V., Tewksbury, D. and Powers, E. (1997) ‘Switching trains of thought. The impact of new frames on reader's cognitive responses’, Communication Research 24: 481–506.

Putnam, R. (2000) Bowling Alone, New York: Simon & Schuster.

Rhee, J.W. (1997) ‘Strategy and issue frames in election campaign coverage: a social cognitive account of framing effects’, Journal of Communication 47 (3): 26–48.

Risse-Kappen, T., Engelmann-Martin, D., Knopf, H-J. and Roscher, K. (1999) ‘To Euro or not to Euro? The EMU and identity politics in the European Union’, European Journal of International Relations 5 (2): 147–187.

Rohrschneider, R. (2002) ‘The democracy deficit and mass support for an EU-wide government’, American Journal of Political Scienc 46 (2): 463–475.

Schuck, A. and de Vreese, C.H. (2006) ‘Between risk and opportunity: news framing of European enlargement and its effects on public support for enlargement’, European Journal of Communication 21 (1): 5–32.

Semetko, H.A. and Valkenburg, P.M. (2000) ‘Framing European politics: a content analysis of press and television news’, Journal of Communication 50 (2): 93–109.

Valentino, N.A., Beckmann, M.N. and Buhr, T.A. (2001a) ‘A spiral for of cynicism for some: the contingent effects of campaign news frames on participation and confidence in government’, Political Communication 18: 347–367.

Valentino, N.A., Buhr, T.A. and Beckmann, M.N. (2001b) ‘When the frame is the game: revisiting the impact of ‘strategic’ campaign coverage on citizen's information retention’, Journalism and Mass Communication Quarterly 78: 93–112.

van der Eijk, C. and Franklin, M.N. (2004) ‘Potential for Contestation on European Matters at National Elections in Europe’, in M. Gary and M.R. Steenbergen (eds.) European Integration and Political Conflict, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 32–50.

Zaller, J. (1992) The Nature and Origins of Mass Opinion, New York: Cambridge University Press.

Zaller, J. (1996) ‘The Myth of Massive Media Impact Revived: New Support for a Discredited Idea’, in D. Mutz, P. Sniderman and R. Brody (eds.) Political Persuasion and Attitude Change, Michigan: Michigan University Press, pp. 17–78.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Appendix

Appendix

Overview of Independent Variables (Study 2)

Gender: Female=1; male 0.

Age: in years.

Education: was recoded in four categories, comparable across the two countries, ranging from 1 (primary school), 2 (high school or equivalent (about 13 years of training)), 3 (BA or 3 years vocational training or equivalent (16 years)), and 4 (Masters or post-graduate training (19+ years)).

Government evaluation: Items ranging from 1 (very bad) to 5 (very good) rating of the incumbent government (Denmark, M=3.93, SD=0.99; the Netherlands, M=2.32, SD=0.93).

Political sophistication: Items ranging from (1) no to (4) high political interest (Denmark, M=3.09, SD=0.70; the Netherlands, M=2.56 SD=0.82).

Media exposure (additive) and attention EU: number of days watching television news (0–7) and reading a newspaper (0–7 in Denmark and 0–6 in the Netherlands) plus attention for EU affairs (ranging from 1 to 4), additive index ranging from 1 to 17/18, Denmark (M=15.74, SD=3.51); the Netherlands (M=12.52, SD=3.49).

Efficacy: Six-item (Likert scale) index forming a scale of efficacy (Denmark, M=16.99, SD=4.10; Cronbach's α is=0.72; the Netherlands, M=16.50, SD=3.59, α=0. 66). (1) at times, politics can be so complex that people like me do not understand what is going on, (2) people like me do not have any say in what the government does, (3) I think that I am better informed about politics than others, (4) MPs want to keep in touch with the people, (5) parties are only interested in people's vote, not their opinions, and (6) there are so many similar parties that it does not matter who is in government.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

de Vreese, C. A Spiral of Euroscepticism: The Media's Fault?. Acta Polit 42, 271–286 (2007). https://doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.ap.5500186

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.ap.5500186