Abstract

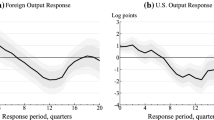

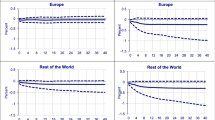

Vector autoregressions of real growth since 1970 are used to estimate spillovers between the United States, the euro area, Japan, and an aggregate of smaller countries proxying for global shocks. U.S. and global shocks generate significant spillovers, but those from the euro area and Japan are small. This paper calculates the standard errors of impulse-response functions, including uncertainty over the proper Cholesky ordering. Extensions adding exports, commodity prices, and financial variables indicate that financial effects are the largest source of spillovers. The results by subperiod underline the importance of the great moderation in U.S. output fluctuations and associated financial stability in lowering output volatility elsewhere.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

See, for example, Canova and Dellas (1993). There are other problems as well. For example, if countries respond differently to some common shock, say, for example, because of differences in economic structure, the estimated common factors may or may not capture the effects of these common shocks, depending on the stringency of the restrictions on the dynamic structure of the underlying model.

Stock and Watson (2005) allow for lagged spillovers of country-specific shocks, but this still leaves contemporaneous shocks unidentified.

For approaches that use Bayesian techniques to update forecasts across models, see Sala-i-Martin, Doppelhofer, and Miller (2004) and Leamer (1978). See Wright (2003) for a discussion and application of Leamer's Bayesian model averaging technique.

Results using alternative groups of countries and weighting schemes produced similar results. The countries included are based on availability of quarterly GDP data since 1970.

Both the final prediction error and the Schwarz information criterion suggest three lags, but the Aikaike information criterion finds one lag to be sufficient.

The disproportionate fall in U.S. volatility is robust to modest changes in the sample period, and is consistent with the results in Stock and Watson (2005) and International Monetary Fund (2007). The source of the great moderation—smaller underlying shocks or better policies—remains a subject of much debate. See Stock and Watson (2003); Juillard and others (2006); and International Monetary Fund (2007).

This is also consistent with the evidence that averaging across a range of models tends to produce better forecasts than a single model. See, for example, Stock and Watson (2004).

These magnitudes are similar to those found by Perez, Osborn, and Artis (2006).

Full results for these orderings, including standard errors, are available from the authors upon request.

Results with standard errors for each period are available from the authors upon request.

See Stock and Watson (2005) and Perez, Osborn, and Artis (2006) for other examples of this approach.

Perez, Osborn, and Artis (2006) found a similar result.

This result is robust to modest changes in the sample, although if the break point is moved after 1993—leaving only one recession in the second period which is probably inadequate for accurately identifying spillovers—there is a stronger role played by moderation of shocks in other regions.

This also keeps the VARs smaller, which conserves degrees of freedom.

Results including the export contribution for the rest-of-world aggregate are similar to those reported here and are available upon request.

Estimation using zero lags showed only minor differences, while trade spillovers were smaller, on average, with four lags. Results for both specifications are available upon request.

Rest-of-world financial conditions are not included. Given that the data already include the largest financial markets and those in other major economies are highly correlated with the regions included here, the rest-of-world financial conditions variable would be unlikely to add a significant amount of information. One indication of the success of this method is that we find sizable financial spillovers from rest-of-world growth shocks even in the absence of a specific measure of the region's financial conditions.

Decompositions based on the individual orderings discussed in the previous section are available from the authors upon request.

Experimentation with other methods of quantifying the trade channel, including making trade an endogenous variable in the VAR, or using net exports' contribution to growth, yielded similar results. A related paper (Swiston and Bayoumi, 2008) examines spillovers to Canada and Mexico and finds that trade spillovers are stronger where there is a large amount of bilateral trade—in that case, from the United States.

Dees and others (2007) come to the same conclusion using a different methodology.

In estimates including each variable separately, they all make sizable contributions to spillovers. Therefore, while monetary policy is an important driver of spillovers, so are financial conditions more generally. Furthermore, the estimate of their joint impact is not much smaller than the sum of their individual contributions, suggesting that the effects of the three financial variables are relatively orthogonal to each other.

References

Baxter, M., and M. Kouparitsas, 2005, “Determinants of Business Cycle Comovement: A Robust Analysis,” Journal of Monetary Economics, Vol. 52 (January), pp. 113–157.

Bayoumi, T., and A. Swiston, 2007, “The Ties that Bind: Measuring International Bond Spillovers Using Inflation-Indexed Bond Yields,” IMF Working Paper 07/128 (Washington, International Monetary Fund). Available via the Internet: www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/wp/2007/wp07128.pdf.

Bordo, M., and T. Helbling, 2004, “Have National Business Cycles Become More Synchronized?” in Macroeconomic Policies in the World Economy, ed. by H. Siebert (Berlin-Heidelberg, Germany, Springer Verlag).

Canova, F., and H. Dellas, 1993, “Trade Interdependence and the International Business Cycle,” Journal of International Economics, Vol. 34 (February), pp. 23–47.

Dees, S., F. Di Mauro, H. Pesaran, and V. Smith, 2007, “Exploring the International Linkages of the Euro Area: A Global VAR Analysis,” Journal of Applied Econometrics, Vol. 22 (January/February), pp. 1–38.

Ehrmann, M., and M. Fratzscher, 2005, “Equal Size, Equal Role? Interest Rate Interdependence between the Euro Area and the United States,” Economic Journal, Vol. 115 (October), pp. 928–948.

Fagan, G., J. Henry, and R. Mestre, 2005, “An Area-Wide Model for the Euro Area,” Economic Modeling, Vol. 22 (January), pp. 39–59.

Faust, J., J. Rogers, S. Wang, and J. Wright, 2007, “The High-Frequency Responses of Interest Rates to Macroeconomic Announcements,” Journal of Monetary Economics, Vol. 54 (May), pp. 1051–1068.

Gerlach, H., 1988, “World Business Cycles under Fixed and Flexible Exchange Rates,” Journal of Money, Credit and Banking, Vol. 20 (November), pp. 621–632.

Gregory, A., A. Head, and J. Raynauld, 1997, “Measuring World Business Cycles,” International Economic Review, Vol. 38 (August), pp. 677–701.

Imbs, J., 2006, “The Real Effects of Financial Integration,” Journal of International Economics, Vol. 68 (March), pp. 296–324.

International Monetary Fund, 2007, World Economic Outlook, October 2007: Globalization and Inequality (Washington, International Monetary Fund).

Juillard, M., P. Karam, D. Laxton, and P. Pesenti, 2006, “Welfare-Based Monetary Policy Rules in an Estimated DSGE Model of the U.S. Economy,” ECB Working Paper No. 613 (Frankfurt, European Central Bank). Available on the Internet at: www.ecb.int/pub/pdf/scpwps/ecbwp613.pdf.

Kose, M., C. Otrok, and C. Whiteman, 2003, “International Business Cycles: World, Region, and Country-Specific Factors,” American Economic Review, Vol. 93 (September), pp. 1216–1239.

Kose, M., C. Otrok, and C. Whiteman, 2005, “Understanding the Evolution of World Business Cycles,” IMF Working Paper 05/211 (Washington, International Monetary Fund). Available via the Internet: www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/wp/2005/wp05211.pdf.

Kose, M., E. Prasad, and M. Terrones, 2004, “Volatility and Comovement in a Globalized World Economy: An Exploration,” in Macroeconomic Policies in the World Economy, ed. by H. Siebert (Berlin-Heidelberg, Germany, Springer Verlag).

Kose, M., and K. Yi, 2006, “Can the Standard International Business Cycle Model Explain the Relation between Trade and Comovement?,” Journal of International Economics, Vol. 68 (March), pp. 267–295.

Leamer, E., 1978, Specification Searches: Ad Hoc Inference with Non Experimental Data (New York, John Wiley and Sons).

Perez, P., D. Osborn, and M. Artis, 2006, “The International Business Cycle in a Changing World: Volatility and the Propagation of Shocks in the G-7,” Open Economies Review, Vol. 17 (July), pp. 255–279.

Pesaran, M., T. Schuermann, and S. Weiner, 2004, “Measuring Regional Interdependencies Using a Global Error-Correction Macroeconomic Model,” Journal of Business and Economic Statistics, Vol. 22 (April), pp. 129–162.

Pesaran, M., and Y. Shin, 1998, “Generalized Impulse Response Analysis in Linear Multivariate Models,” Economics Letters, Vol. 58 (January), pp. 17–29.

Sala-i-Martin, X., G. Doppelhofer, and R. Miller, 2004, “Determinants of Long-Term Growth: A Bayesian Averaging of Classical Estimates (BACE) Approach,” American Economic Review, Vol. 94 (September), pp. 813–835.

Stock, J., and M. Watson, 2003, “Has the Business Cycle Changed and Why?” in NBER Macroeconomics Annual (Cambridge, Massachusetts, National Bureau of Economic Research).

Stock, J., and M. Watson, 2004, “Combination Forecasts of Output Growth in a Seven-Country Data Set,” Journal of Forecasting, Vol. 23 (September), pp. 405–430.

Stock, J., and M. Watson, 2005, “Understanding Changes in International Business Cycle Dynamics,” Journal of the European Economic Association, Vol. 3 (September), pp. 968–1006.

Swiston, A., and T. Bayoumi, 2008, “Spillovers Across NAFTA,” IMF Working Paper 08/03 (Washington, International Monetary Fund). Available via the Internet: www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/wp/2008/wp0803.pdf.

Wright, J., 2003, “Bayesian Model Averaging and Exchange Rate Forecasts,” International Finance Discussion Paper 2003-779 (Washington, Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System). Available via the Internet: www.federalreserve.gov/pubs/ifdp/2003/779/ifdp779.pdf.

Additional information

*Tamim Bayoumi is an assistant director with the IMF's Western Hemisphere Department, and Andrew Swiston is a research assistant with that department. The authors gratefully acknowledge invaluable contributions from Sam Ouliaris and Thomas Helbling. Useful comments were also received from Petya Brooks, Trish Pollard, Nathan Sheets, Jeromin Zettelmeyer, participants in a seminar with U.S. government officials, participants in a Western Hemisphere Department seminar, and participants in an IMF seminar on the Macroeconomic and International Implications of Financial Market Innovation.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Bayoumi, T., Swiston, A. Foreign Entanglements: Estimating the Source and Size of Spillovers Across Industrial Countries. IMF Econ Rev 56, 353–383 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1057/imfsp.2008.23

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/imfsp.2008.23