Abstract

Discussions of efficiency among Historically Black Colleges and Universities (HBCUs) are often missing in academic conversations. This article seeks to assess efficiency of individual HBCUs using Data Envelopment Analysis (DEA), a non-parametric technique that can synthesize multiple inputs and outputs to determine a single efficiency score for each institution. The authors hypothesized that institutions with higher endowments will have higher efficiency scores due to an increased ability to acquire more productive capital. To test this hypothesis, efficiency scores were regressed on endowments and HBCU status, with control variables denoting if institutions are public or religiously affiliated. From DEA, we found that HBCUs were on average slightly more efficient that Predominantly White Institutions. Endowment levels were found to be significant determinants of efficiency for both sets of institutions. This suggests (1) that the general perception of HBCUs as inefficient requires reconsideration and (2) that schools with the most endowment resources are generally more efficient. Less efficient HBCUs should perhaps devote resources to building endowment levels to increase efficiency. We can also see the importance of methodologies allowing for investigation of both differences among HBCUs and differences in operational contexts among HBCUs and other schools.

Similar content being viewed by others

Scholars have shown the value to American higher education of Historically Black Colleges and Universities (HBCUs) (Constantine, 1995; Nettles and Perna, 1997; Ehrenberg et al, 1999; Matthews and Hawkins, 2007). However, the schools’ academic and financial struggles have led policy makers to consider significant structural changes in HBCUs, including mergers and, in some cases, elimination (Cohen, 2008).

A central academic goal of HBCUs is to produce graduates with bachelors’ degrees. Unfortunately, HBCUs often have graduation rates significantly below national averages, sometimes in the teens (National Center for Education Statistics, 2006). This is, in part, due to the tendency of HBCUs to admit students who otherwise would be under-qualified for pursuit of post-secondary education. But, nonetheless, low graduation rates increase the cost per graduate, and pose problems when petitioning for operating and endowment funds from governments, nonprofit institutions, and individuals who have attended the school.

Indeed, HBCUs are often faced with fiscal constraints that are even more stringent than those of their Predominantly White Institution (PWI) counterparts. Compared to PWIs, HBCUs find it more difficult to obtain funding from government and other institutions, and also face difficulty in increasing their endowments, with the persistence of these disadvantages well documented in literature (Gasman and Sedgwick, 2005; Hale, 2007). Further, HBCUs have historically sought to enroll and graduate African-American students of low financial means, who are less able to pay tuition commensurate with that of many PWIs (Gasman and Epstein, 2006). As a result, tuition rates at many HBCUs are lower than those of the PWIs, further decreasing institutional revenues.

In short, many HBCUs seek to accomplish their primary mission of graduating African-Americans with shortages of financial resources to do so, including insufficient funding from state and institutional sources, insufficient levels of tuition, and insufficient endowments.

THE ROLE OF EFFICIENCY, AND THE POSSIBLE EFFECTS OF ENDOWMENT LEVEL ON IT

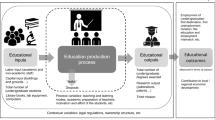

Although insufficient by itself, an internal mechanism for increasing the number of graduates without a proportional increase in financial resources is to improve organizational efficiency. Efficiency, more commonly known as productivity, is the ratio of outputs to inputs. A simple example for the current case is number of graduates divided by operating expenses. If more graduates can be produced without increasing expenses (or if the same number of graduates can be produced with lower expenses), then efficiency has improved, thereby helping HBCUs to achieve their mission without additional resources.

While the institutional efficiency of HBCUs has not been investigated scientifically, policy makers have cited it as a motivating factor in the proposed restructuring of HBCUs. A well-known example took place in Mississippi. A proposal was considered suggesting the consolidation of Mississippi Valley State University, Alcorn State University and Jackson State University to alleviate financial strains faced by both the institutions and the state of Mississippi. Recently, financial shortcomings resulted in the temporary revocation of accreditation of Fisk University, Kentucky State University and North Carolina Central University. Similar financial problems resulted in Texas Southern University's placement on probation (Diverse Issues in Higher Education, 2009). Since efficiency lies at the forefront of policy debates around the restructuring of HBCUs, it seems increasingly important that we investigate, empirically, the organizational efficiency of HBCUs, including comparisons between HBCUs and PWIs with the similar organizational goal of graduating students.

One potential influence on educational efficiency might be the level of endowments. Endowment monies that are used to obtain capital items would not be reflected in operating expenses. These capital enhancements might include things such as more extensive library collections, better classroom and other academic facilities conducive to student learning, better computer equipment and better lab facilities, to name just a few. And, larger endowments might be used to provide more financial support to students so less of their time is spent on working to pay their expenses and more of their time can be spent on academic matters.

PURPOSE AND ORGANIZATON OF THIS ARTICLE

The purpose of this article is to (1) present a well-known and economically valid efficiency indicator that nevertheless has not been employed for estimating HBCU efficiency, (2) measure the relative efficiency of individual HBCUs and PWIs with this indicator, and (3) estimate the effects of endowments on the HBCU efficiency scores.

We first describe the efficiency measurement methodology. Then, we apply the method to a pooled sample of HBCUs and PWIs, and compare the results for the two groups. Next, we regress the efficiency scores previously obtained on the level of endowments, with appropriate control variables including whether the school is an HBCU or a PWI. Finally, we present our conclusions, including implications for public policy, for HBCU management, and for advancement professionals.

MEASURING EFFICIENCY WITH DATA ENVELOPMENT ANALYSIS

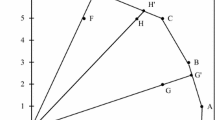

To identify the relative efficiency of each school, we use a methodology that often is called Data Envelopment Analysis (DEA). DEA uses linear programming to produce a single, comprehensive efficiency measure, by choosing optimal weights in the ratio of weighted aggregated outputs to weighted aggregated inputs – with fully efficient organizations scoring exactly 100 percent. The efficiency of a given organization is expressed as a percentage of the efficiency of its most efficient peers. Therefore, if a target school's DEA score is not 100 percent, this tells us that other colleges and universities in the sample are still more efficient. Once DEA efficiency levels for each school have been identified, the schools can be analyzed by other methods to determine why some are more efficient than others.

A key feature of DEA is that the weighting for variable aggregation can be different for each individual organization. For the target organization, weights are assigned so that the organization will obtain the highest possible efficiency score when it is compared to its peers, when all have been assigned the particular set of weights that is optimal for the target organization. Therefore, no organization can argue that its score would have been higher if only different weights were used. The use of weights can be best seen in the ratio form of the DEA model, which computes the efficiency score for target school k′ (Equation Set 1):

There are j schools to be evaluated (j=1, …, J), so the program must be run J times, with each school being the target once. The target school is designated school k′. Each school consumes varying amounts of n different inputs (n=1, …, N) to produce m different outputs (m=1, …, M). Thus, for example, school j consumes amount x nj of input n and produces y mj of output m. For all schools, u m is the weight by which each y mj is multiplied, and v n is the weight by which each x nj is multiplied. The school that is the target of a given evaluation is designated school k′, and it is compared to all J schools. The program maximizes the target school's ratio of weighted outputs to weighted inputs. The weights u m and v n are the variables, and they are changed until the ratio is maximized for the target school when those same weights are applied to all schools. The value of the ratio θ is the efficiency score of school k′, where 0⩽θ⩽1 and a fully efficient school receives a score of 1. Again, note that it is the weights that are the variables, with the outputs and inputs being the values actually observed for each school.

DEA was initially developed to measure the efficiency of educational activities (Charnes et al, 1978, 1981), and has been extensively used to evaluate efficiency in educational institutions at all levels since its introduction. A comprehensive list of DEA applications to educational organizations is available in the International Handbook on the Economics of Education (Johnes, 2004), and an examination of DEA applications to schools at all levels can be found in the Handbook of Data Envelopment Analysis (Cooper et al, 2004). A few examples of its use to evaluate institutions of higher education include (Beasley, 1990, 1995, 2003; Breu and Raab, 1994; Athanassopoulos and Shale, 1997; Avkiran, 2001; Korhonen et al, 2001; Abbott and Doucouliagos, 2003; Casu and Thanassoulis, 2006; Glass et al, 2006; Worthington and Lee, 2008).

Although its validity and utility for measuring educational efficiency is well documented, DEA heretofore has not been employed for evaluating the efficiency of HBCUs.

ESTIMATING HBCU EFFICIENCY WITH DEA

Data for this study were published by the federally funded Integrated Post Secondary Education System (IPEDS), and we use data from the 2005–2006 academic year. Because HBCU organizational missions do not systemically differ from one another, private and public HBCUs were pooled and DEA was run for both sets of institutions concurrently. PWIs selected for analysis are similar in mission to HBCUs in that they primarily devote resources to undergraduate students. Selection of these PWIs was done using Carnegie Classification 2005 (Carnegie Commission on Higher Education, 2006). HBCUs with significant research output, and graduate/professional programs were excluded from analysis. For that reason, Howard University was excluded from this study. Means, maximums and minimums of the data are represented in Table 1.

Table 2 describes the inputs selected to examine HBCUs and similar PWIs. Because the literature suggests graduation of students is the primary mission of HBCUs, output selection was limited to number of bachelor's degrees conferred.

SAT median scores were used as inputs to the production process to control for student selectivity, citing the tendency of HBCUs and some PWIs to select for students who are typically less prepared for post-secondary education. Median scores were used. The ACT/ACT conversion chart published by the American Collegiate Testing board (ACT, 2010) was used to convert ACT scores for schools only reporting ACT scores.

Because schools that admit more students should theoretically graduate more students, Full-Time Enrollment was an included input. Institutional, academic and student support expenditures were considered inputs as vital components to graduating students. Other operating costs were computed for each school subtracting the above academic, institutional and student support expenditures, along with research expenditures, from total institutional operating expenditures.

DEA RESULTS

We ran DEA concurrently for a pooled sample of HBCUs and PWIs, so their efficiency scores could be compared. Table 3 provides a summary of the DEA efficiency estimates, by type of school.

As shown in Table 3, the claim that HBCUs as a whole are less efficient than PWIs would be rejected at any standard level of statistical significance. Indeed, mean efficiency score of HBCUs is actually higher than that of the PWIs’. HBCUs are also over represented on the efficiency frontier, with 17 percent of HBCUs qualifying as efficient, compared to 12 percent of PWIs. There were also more PWIs than HBCUs in the group with very low (0.16–0.49) scores. From the minimum scores reported for both HBCUs and PWIs, we observe the large ranges in scores for both subgroups. Both subgroups have minimum scores below 20 percent efficiency. Recall that these scores do not measure absolute efficiency, but efficiency relative to the most efficient schools, with the most efficient schools being assigned an efficiency score of 1. Thus the low scores do not indicate low absolute efficiency, but only low efficiency compared to the most productive schools, thereby indicating much room for improvement but giving no information about absolute efficiency.

ENDOWMENT AS AN EFFICIENCY DETERMINANT

We hypothesized that colleges and universities that have larger endowments also might be more efficient. Increased levels of endowment might allow institutions to purchase improved human and physical capital, perhaps more qualified administrative staff or faster machinery. Additionally, we wished to test whether or not endowment levels had different effects on efficiency for PWIs and HBCUs. We used public/private institution and religious institution as control variables. The functional relationship to be estimated is shown by Equation (2).

Efficiency is a vector of DEA efficiency scores and Endow is a vector of year-end endowment levels for each institution. Endowments were multiplied by 10×E−09 and thus measured in billions, so their numerical values would be approximately the same size as the Efficiency variable (0⩽θ⩽1). Variables HBCU, Public and Religious are vectors of dummy variables coded for status as an HBCU, public institution and religiously affiliated institution respectively. Robust standard errors were used to adjust for heteroskedasticity and autocorrelation effects. Interactions between endowment level and HBCU were not statistically significant, so they are not included in equation (2) or the results we report herein (Table 4).

As can be seen, endowment is indeed related to efficiency to a statistically significant degree, as is endowment squared. This is also true when the five schools with very large endowments were included. There was no statistically significant effect on either the efficiency intercept, or slope of endowment, by whether the school was a HBCU or a PWI. Because endowment values are in billions, all of the schools’ values are less than 1, leading to very small values for endowment squared and hence a large regression coefficient for the squared term. However, it should be noted that endowments continue to increase throughout the entire endowment range (including the very-large endowment schools), but, even without the five schools, the marginal influence of endowment level on efficiency became slightly less positive as endowment size grows. That is, the regression coefficient of endowment shows a positive slope, indicating that the larger the endowment, the higher the efficiency. The regression coefficient of the endowment squared variable has a negative slope, which means that the efficiency growth predicted by a growth in endowment becomes increasingly smaller as the overall size of the endowment grows. This is a common economic phenomenon, ‘decreasing returns to scale’.

IMPLICATIONS FOR PUBLIC POLICY

From these results, it would appear that the perception of HBCUs as inefficient institutions (Minor, 2004) might be largely inaccurate. We found that, on the average, HBCUs were at least as efficient as their PWI counterparts, and possibly more efficient. Perhaps HBCUs are not systematically inefficient, but, on average, under-resourced. Organizational activity that appears to be inefficient might be better understood as organizational processes not sufficiently funded to keep up with the organizational mission, that is, five individuals employed in a financial aid office tasked with processing an overwhelming number of applications. Should our results be borne out by further empirical analyses, policy decisions made on the assumption that HBCUs are less efficient than PWIs would need to be reconsidered.

Additionally, given the high variance in efficiency scores of HBCUs, we believe policy makers and researchers should make further attempts to distinguish efficient HBCUs from inefficient ones, through rigorous quantitative and qualitative analyses. While HBCUs share some similarities, the wide spectrum of organizational performance suggests efficient HBCUs might benefit more than inefficient ones from increased public and private investment.

IMPLICATIONS FOR HBCU MANAGEMENT

One can see from the large range of DEA scores in both HBCU and PWI institutions that there is a need for careful examination of individual schools. HBCUs have much in common with each other, but the range of relative efficiency scores suggests that organizational structures and processes differ among HBCUs to the extent that there are drastic differences in organizational performance. We suggest that far more investigation take place examining the ways in which HBCUs differ, emphasizing perhaps successful organizational structures at efficient institutions. Less efficient educational institutions might learn from those with higher efficiency scores, as has been true for other fields (Cooper et al, 2004; Barnum et al, 2008; Schumock et al, 2009; Welch and Barnum, 2009).

Further, HBCU managements should, in our opinion, use DEA as the central analytical tool for evaluating the efficiency of departments and other units within their schools. Abbott and Doucouliagos (2003) use DEA to compare research output across several economics departments in Australia, and DEA has been used to evaluate inter-departmental efficiency in both the private and public sectors. A more complete discussion of the uses of DEA in evaluating efficiency in higher education is available in Johnes (2006a, 2006b), and we believe that similar analyses would be valuable for individual HBCUs.

IMPLICATIONS FOR ADVANCEMENT PROFESSIONALS

The apparent relationship between endowments and efficiency, if confirmed through institutional case studies and further quantitative analysis, would support an increasingly central role for advancement efforts. We believe that larger endowments result in higher efficiency. Institutions with more money to spend are likely to have increased opportunities to invest in equipment, people and activities that make them more efficient. For instance, the ability to replace outdated computer hardware with more modern equipment could make students and faculty members generally more productive.

That is, our findings suggest that resources channeled to increasing endowments instead of applying the funds directly for education may make the institution more efficient in providing the education. Given a positive relationship between endowment size and the resources devoted to obtaining donations, switching resources from direct education to fundraising could result in more graduates for the same total resource input, making the argument for such switches more compelling.

On another note, to the degree that endowment size and organizational efficiency are positively related, institutions should more closely monitor the performance of university market investments. This may involve setting clear goals to fund managers for expected returns on investments, and devoting time to finding the mix of investments that best grows the institution's endowments.

Even if the cause-effect is that high efficiency results in more donations, the relationship can be exploited to the advantage of the institutions. If efficiency is measured consistently by advancement professionals, an institution's relative efficiencies can be communicated to donors, further encouraging donations.

In summary, we suggest that HBCUs that have not made fundraising and endowment-building an institutional priority should devote more resources to this activity, even given the resulting decreased commitment to other university functions. The net benefit of such resource redistributions may well be the production of more graduates for the same amount of money. Also, increased institutional efficiency might make a department or institution more attractive to potential donors by increasing donor confidence that donated resources will be used wisely. Because HBCUs face increasing financial obstacles, we believe these conclusions are worthy of careful consideration.

References

Abbott, M. and Doucouliagos, C. (2003) The efficiency of Australian universities: A data envelopment analysis. Economics of Education Review 22 (1): 89–97.

American Collegiate Test. (2010) ACT-SAT Concordance, http://www.act.org/aap/concordance/index.html, accessed 31 March 2010.

Athanassopoulos, A.D. and Shale, E. (1997) Assessing the comparative efficiency of higher education institutions in the UK by means of data envelopment analysis. Education Economics 5 (2): 117–134.

Avkiran, N.K. (2001) Investigating technical and scale efficiencies of Australian Universities through data envelopment analysis. Socio-Economic Planning Sciences 35 (1): 57–80.

Barnum, D.T., Tandon, S. and McNeil, S. (2008) Comparing the performance of bus routes after adjusting for the environment, using Data Envelopment Analysis. Journal of Transportation Engineering 134 (2): 77–85.

Beasley, J.E. (1990) Comparing university departments. Omega 18 (2): 171–183.

Beasley, J.E. (1995) Determining teaching and research efficiencies. Journal of the Operational Research Society 46 (4): 441–452.

Beasley, J.E. (2003) Allocating fixed costs and resources via data envelopment analysis. European Journal of Operational Research 147 (1): 198–216.

Breu, T.M. and Raab, R.L. (1994) Efficiency and perceived quality of the nation's ‘top 25’ National Universities and National Liberal Arts Colleges: An application of data envelopment analysis to higher education. Socio-Economic Planning Sciences 28 (1): 33–45.

Carnegie Commission on Higher Education. (2006) Carnegie Classification 2005, http://nces.ed.gov/ipeds/datacenter/InstitutionByGroup.aspx, accessed 4 March 2010.

Casu, B. and Thanassoulis, E. (2006) Evaluating cost efficiency in central administrative services in UK universities. Omega 34 (5): 417–426.

Charnes, A., Cooper, W.W. and Rhodes, E. (1978) Measuring the efficiency of decision making units. European Journal of Operational Research 2 (6): 429–444.

Charnes, A., Cooper, W.W. and Rhodes, E. (1981) Evaluating program and managerial efficiency: An application of data envelopment analysis to program follow through. Management Science 27 (6): 668–697.

Cohen, R.T. (2008) Alumni to the rescue: Black college alumni and their historical impact on alma mater. International Journal of Educational Advancement 8: 25–33.

Constantine, J. (1995) The effect of attending historically black colleges and universities on future wages of black students. Industrial and Labor Relations Review 48: 531–546.

Cooper, W.W., Seiford, L.M. and Zhu, J. (eds.) (2004) Handbook of Data Envelopment Analysis. Boston, MA: Kluwer.

Diverse Issues in Higher Education. (2009) Accreditation reaffirmed for Fisk University, 3 other HBCUs, http://diverseeducation.com/article/13258/accreditation-reaffirmed-for-fisk-university-three-other-hbcus.html, accessed 14 March 2010.

Ehrenberg, R., Rothstein, D. and Olsen, R. (1999) Do historically black colleges and universities enhance the college attendance of African–American youths? In: P. Moen, D. Demster-McClain and H. Walker (eds.) A Nation Divided. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

Gasman, M. and Sedgwick, K. (eds.) (2005) Uplifting a People: African American Philanthropy and Education. New York: Peter Lang.

Gasman, M. and Epstein, E.M. (2006) Creating and image for black college fundraising: An illustrated examination of the United Negro college fund's publicity, 1944–1960. In: M. Gasman and K. Sedgwick (eds.) (2005) Uplifting a People: African American Philanthropy and Education. New York: Peter Lang, pp. 65–88.

Glass, J.C., McCallion, G., McKillop, D.G., Rasaratnam, S. and Stringer, K.S. (2006) Implications of variant efficiency measures for policy evaluations in UK higher education. Socio-Economic Planning Sciences 40 (2): 119–142.

Hale, F.M. (2007) Introduction. In: F.M. Hale (ed.) How Black Colleges Empower Black Students: Lessons for Higher Education. Sterling, VA: Stylus, pp. 5–13.

Johnes, J. (2004) Efficiency measurement. In: G. Johnes and J. Johnes (eds.) International Handbook on the Economics of Education. Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar, pp. 613–670.

Johnes, J. (2006a) Measuring efficiency: A comparison of multilevel modelling and data envelopment analysis in the context of higher education. Bulletin of Economic Research 58 (2): 75–104.

Johnes, J. (2006b) DEA and its application to the measurement of efficiency in higher education. Economics of Education Review 25 (3): 273–288.

Korhonen, P., Tainio, R. and Wallenius, J. (2001) Value efficiency analysis of academic research. European Journal of Operational Research 130 (2001): 121–132.

Matthews, F.L. and Hawkins, D.B. (2007) Black colleges: Still making an indelible impact with less. In: F.M. Hale (ed.) How Black Colleges Empower Black Students: Lessons for Higher Education. Sterling, VA: Stylus, pp. 5–13.

Minor, J.T. (2004) Decision making in historically black colleges and universities: Defining the governance context. The Journal of Negro Education 73 (1): 40–52.

National Center For Education Statistics. (2006) Integrated Post Secondary Education Data System, http://nces.ed.gov/ipeds/datacenter/Default.aspx, accessed 14 March 2010.

Nettles, M.T. and Perna, L.W. (1997) The African American Education Data Book. Vol. 1: Higher and Adult Education. Fairfax, VA: United Negro College Fund, Frederick D. Patterson Research Institute.

Schumock, G.T., Shields, K.L., Walton, S.M. and Barnum, D.T. (2009) Data envelopment analysis – A method for comparing hospital pharmacy productivity. American Journal of Health-System Pharmacy 66 (18): 1660–1665.

Welch, E.W. and Barnum, D.T. (2009) Joint environmental and cost efficiency analysis of electricity generation. Ecological Economics 69 (8): 2336–2343.

Worthington, A.C. and Lee, B.L. (2008) Efficiency, technology and productivity change in Australian universities, 1998–2003. Economics of Education Review 27 (3): 285–298.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Coupet, J., Barnum, D. HBCU efficiency and endowments: An exploratory analysis. Int J Educ Adv 10, 186–197 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1057/ijea.2010.22

Received:

Revised:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/ijea.2010.22