Abstract

Universities today need to become quicker on their toes. They must continually scan the environment and seize emerging opportunities – and institutional advancement must lead this effort. An unfortunate number of institutional advancement operations are ill equipped for the task at hand. Many suffer from high staff turnover and overly hierarchical systems that reflect excessive fragmentation and compartmentalization. They inadvertently perpetuate stifling and unnecessary bureaucracy. Organizing advancement efforts around the metaphor of the design studio or creative workshop promises to (a) pool talent, (b) cultivate collaboration, and (c) align diverse but related interests in order to promote fruitful advancement. By shifting the way personnel and leaders conceptualize their work, institutional advancement can overcome a number of challenges that currently hinder its efforts. The Institutional Advancement Atelier described in this paper can improve advancement's overall productivity and its ability to see and harness opportunities in a quickly changing environment – and increase employee satisfaction in the process.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

INTRODUCTION

In today's economic and political environment, universities must become increasingly adaptive. They must prepare to address unforeseen events, opportunities and crises in ways that not only promote their continued existence, but also align with their missions and help them achieve their goals (Rowley et al, 1997). This paper explores how universities can utilize a collaborative studio format to organize and reinvigorate university functions such as institutional advancement in increasingly productive ways.

Institutional advancement represents a collection of support services that, while varying from one institution to the next, typically includes fundraising as well as public and alumni relations (Lauer, 2006). By organizing institutional advancement into a set of interdependent collaborative studios, a university can enhance its own ability to fruitfully engage emerging issues and harness relevant opportunities. The studio format that is commonly employed in design fields promotes quick, creative action. It can help overcome many of the limitations inherent to bureaucratic structures that rely on vertical hierarchy and that inadvertently suppress creativity and pluralistic thinking.

Today's academic organizations need to work in an increasingly collaborative manner (Chaffee, 1985; Gordon et al, 1993; Mieczkowski, 1995; Bush and Coleman, 2000; Lauer, 2006; Mortimer and Sathe, 2007). They must integrate previously segregated components – strengthening connections and cultivating human ingenuity – in order to develop creative new solutions to emerging problems and issues. ‘People throughout the institution will have to come out of their boxes and work together for the common good,’ asserts Lauer (2006, p. 25). ‘The silos will have to break down and teams form to advance the whole institution with as much energy as advancing the schools and colleges within it.’ The studio format represents a mainstay of creative design industries – it provides an ideal and well-established model for promoting inventive, proactive and increasingly productive responses to unfolding events and opportunities that confront academia.

THE PRESS FOR CHANGE

Change is everywhere. Kunstler (2005) states that ‘it is not only technology that is changing, or even the categories of knowledge and interpretation, it also the nature of cognition and information processing itself’ (p. 181). Magsaysay (1997) describes a profound transformation underway that is reshaping work, society and family. He says that whereas organizations of the twentieth century were typified by

stability and predictability, size and scale, top-down leadership, control by rules and hierarchy, closely guarded information, quantitative analysis, need for certainty, reactivity and risk aversion, corporate independence, vertical integration, focus on internal organization, sustainable advantage, and the capacity to compete for today's markets

organizations of twenty-first century are moving toward

discontinuous change, speed and responsiveness, leadership from everybody, permanent flexibility, control by vision and values, shared information, creativity and intuition, tolerance of ambiguity, proactive and entrepreneurial initiatives, corporate interdependence, ‘virtual’ integration, focus on the competitive environment, constant reinvention of advantage, and the creation of tomorrow's market (Rowley, Lujan and Dolence, 1998, p. 110).

LINEAR METAPHORS

University planners, including leaders in institutional advancement, have relied on traditional business models, and have borrowed most heavily from rational, linear modes of doing business (Rowley, Lujan and Dolence, 1998; Presley and Leslie, 1999). Although many universities strive for flexibility, their departmentalized structures often hinder their agility. Chaffee (1985) asserts that successful planning uses a combination of three different paradigmatic perspectives: (a) rational analysis; (b) flexibility and adaptability to changing contexts; and (c) some kind of metaphor that fosters future-oriented vision and active interpretation.

There is a high level of agreement among planning scholars that the metaphors used in administering higher education are excessively mechanistic – that they are overly reliant on linear, Newtonian, cause-and-effect reasoning that is ill suited to the realities of academia today. Presley and Leslie (1999), Rowley et al (1997), Shahjahan (2005), and Swenk (2001) all agree that the linear business models typically employed in the business and planning of higher education inadequately address the complex variables found in academic settings.

OVER-RELIANCE ON TRADITIONAL HIERARCHIES

Although excessive compartmentalization needlessly restricts a university's ability to respond quickly, effectively and proactively, it is pervasive within institutional advancement today. ‘The world is changing faster than the governance structure’ assert Mortimer and Sathe (2007, p. 1). They tout the benefits of sharing authority in a way that enhances institutional responsiveness. In fact, Bush and Coleman (2000), Chaffee (1985), Lauer (2006), Gordon et al (1993), Mieczkowski (1995), and Mortimer and Sathe all recommend that universities dissolve superfluous boundaries.

Mieczkowski (1995) indicates that traditional academic hierarchies frequently protect individuals’ sense of power at the expense of the greater good. Vertical hierarchies have come to represent a ‘displacement of goals’ (p. 9) from the collective to the individual. According to Mieczkowski, vertical hierarchies often encourage isolationist protectionism and suppress healthy competition – perpetuating self-serving action that individuals use to accumulate status and material wealth. Traditional structures inadvertently promote stagnation at the top and enable a veritable caste system, he says. ‘Since the 1970's there has been a gradual realization that formal models are ‘at best partial and at worst grossly deficient’ (Chapman, 1993, p. 215 quoted in Bush and Coleman, p. 44).

Bush and Coleman (2000) identify conceptual pluralism as a means to overcome the formal and bureaucratic models that ‘dominated the early stages of theory development in educational management’ (p. 44). Creating metaphors that encompass more diverse ideas and perspectives can help address current problems. Gordon et al (1993) also recommend dismantling ineffective organizational strategies that silo people and tasks into units and sub-units that are highly differentiated. They indicate that such structures have little use in times of rapid change and high uncertainty, and that better integration of units and activities is essential today.

OVERCOMING DYSFUNCTION WITHIN ADVANCEMENT

Lauer (2006) uses a metaphor of a three-legged stool to describe the areas typically associated with institutional advancement: (a) development/fundraising, (b) communications/institutional relations, and (c) alumni relations. Unfortunately, the connections between these activities are often tenuous or unacknowledged, which hampers their efficacy. The proposed Atelier unites all three legs of Lauer's ‘stool’ into one single structure, and aligns them with a number of other associated functions to (a) mitigate the harmful effects of fragmentation, (b) build momentum and collective vision, and (c) catalyze proactive, creative and strategic thinking.

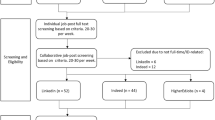

The organizational chart for a new Institutional Advancement Atelier (shown in Figure 1) includes strategic planning, government relations, admissions and student relations, master and architectural planning, as well as some aspects of athletic fundraising. All of these occur alongside traditional advancement functions of development, media and alumni relations. This format reflects and extends a current trend identified by Lauer (2006), who indicates that in order to overcome ineffective fragmentation, a number of institutions have already decided to group admissions with institutional advancement's more traditional activities of marketing and communication.

Organizational chart for a new studio for institutional advancement. (Chart developed using studies by Hall and Baker, 2003; Nichols State University, 2007; North Carolina State University, 2007; Siena Heights University, 2007; Coulter, 2008; Old Dominion University, 2008; James Madison University Office of Human Resources, n.d.; University of Tennessee at Martin, n.d.).

Lauer (2006) explains that some universities have gone as far as to move marketing and communication out of advancement altogether in order to more effectively align the messages they convey with admissions processes. As more and more institutions struggle to effectively align various advancement functions in order to achieve coherence of purpose and action, the use of the studio model makes more and more sense. Pooling diverse talents and perspectives can serve as a remarkable catalyst for growth. However, Gordon et al (1993) caution that personnel serving in various branches of advancement often have very different emotional and cognitive orientations. Such differences need to be acknowledged by leaders as they seek to create integrated and cohesive advancement organizations.

The Atelier model incorporates a number of recommendations proposed by Iarrobino (2006) to alleviate the turnover rampant within today's advancement profession. High turnover detrimentally affects institutions’ ability to deliver coherent messages and build stable external relationships. Iarrobino identifies personnel policies as the primary cause of this troubling phenomenon.

Iarrobino's (2006) research indicates a number of issues that must be incorporated into the new Atelier model to help ensure its success, including (a) a collectively constructed vision; (b) increased availability of supervisors and colleagues; (c) effective communication (with feedback, praise and constructive critique); (d) well-formulated and widely understood strategies for business and hiring; (e) competency-based performance criteria and reward systems; (f) improved flexibility (in scheduling, comp-time and opportunities to work from home); and (g) access to professional development, promotion and new learning experiences. These features can all contribute to turning the current epidemic around. They are all either inherent to the Atelier model or easily integrated into it. Attention to these issues can help create an environment where individuals feel they are valued – which Iarrobino indicates is absolutely essential to retaining a happy and productive advancement team.

EMERGING METAPHORS

Scholars across the board agree: Universities must learn new ways of thinking that (a) prompt continual learning and (b) enhance outcomes by effectively using both formative and summative feedback. In this effort, researchers have proposed a range of new metaphors that they believe can help overcome latent assumptions that commonly hinder growth. Rowley, Lujan, and Dolence (1998), for instance, emphasize that institutions must shed their mechanistic and deterministic traditions and develop more proactive behaviors. Bess and Dee (2008) agree. They assert that universities typically assume positivist orientations in their operations – despite the current existence of diverse paradigms for institutional organization that fall into three broad categories: (a) positivism, (b) social constructionism, and (c) postmodernism.

Rowley, Lujan, and Dolence (1998) are among the scholars who discuss using new metaphors to alleviate problems existing in academia. They assert that institutions that take a role in shaping new paradigms will reap the greatest educational and economic benefits. This requires quickly overcoming the self-limiting mechanistic/positivistic metaphors that most institutions currently employ.

Popular new metaphors include the helix-shaped spring (Wilson, 1997), the cybernetic learning organization (Birnbaum, 1988) and the strange attractors inherent to chaos theory that help align kindred forces (Cutright, 2001). In similar fashion, Gordon et al (1993) encourage using the metaphor of systems theory to promote horizontal linkages within universities and to ‘shape an integrated system of interdependent components’ (p. 7).

As in the proposed Atelier, Gordon et al's ‘optimal organizational structure uses both differentiation and integration to fit the demands of the particular environment’ (1993, p. 7). In this systems perspective, individual units are viewed as dependent upon each other for optimal functioning of the organization; they work together to achieve collective goals and can accomplish much more together than alone.

Bess and Dee (2008) do, however, caution that the positivist paradigm with its vast limitations was also based in systems thinking. To help academic administrators think more holistically, they propose a modified version that they call social systems theory. This metaphor requires simultaneously considering both individual (that is ideographic) and environmental (that is nomothetic) conditions, and offers an appropriate way of implementing the Atelier model.

DESIGN METAPHORS AND THE ATELIER MODEL

This paper proffers a new metaphor – that of the design studio or atelier – as a more-connective, less-hierarchical way of working that fosters creativity and ingenuity. The word atelier is common among western languages, and is often used interchangeably with the English word studio. Both terms refer to an artist's workshop, a place where art or architecture is taught, or a location where skilled workers produce art or other finely crafted objects. The design studio is also commonly conceptualized as an experimental design laboratory or workshop.

In reality, the studio functions much like a conventional newsroom, where people work in a wide-open space to actively refine a product that involves some sort of communication. Workers in the design studio endeavor to envision and/or create meaningful products. Like strategic planners, they normally develop an overarching concept or vision that helps define and unify their creations. This overarching concept mirrors the vision statement created in higher education; Kouzes and Posner (1995) and Fullan (2001) indicate that vision is a critical aspect of good leadership as well.

With institutional advancement, the primary craft is, in fact, communication. Larsen (2003) emphasizes the importance of communication in shaping institutional reputation in his analysis of U.S. News and World Report rankings. The studio format promises to help strengthen advancement's understanding and communiqué of the university's vision by enhancing both internal and external communication. The Atelier model will foster greater consistency among the messages delivered by advancement personnel, as development, government relations, communications, strategic planning, student and alumni relations will all work in close proximity and communicate regularly.

Frequent communication can help overcome an ongoing criticism of higher education – namely that universities often ignore their own vision statements and respond to changing events haphazardly. As such, universities stand to benefit from incorporating successful design strategies. Design techniques include continually scanning the environment for unique opportunities as well as defining coherent and meaningful concepts/goals/visions to guide decision-making. Strategies employed in the design professions reflect the sort of non-linear, iterative and synthesizing processes that scholars such as Birnbaum (1988), Cutright (2001), Presley and Leslie (1999), Rowley, Lujan and Dolence (1998) and Swenk (2001) recommend universities use to improve the effectiveness of strategy-formation and planning.

Lauer (2006) also identifies the importance involving designers and integrating design thinking into university governance – especially in strategic planning and management where creativity traditionally lags. According to Lauer, FastCompany magazine dedicated its June 2005 issue to exploring ways that product designers, architects, creative writers, and the like have spring-boarded an array of planning projects. Lauer recommends involving creative thinkers and designers at the earliest stages of any planning process. He recommends looking to non-advancement entities for organizational precedents, as this paper proposes.

Using the studio metaphor provides a way to re-conceptualize how institutional advancement operates, to more effectively harness the creative potential of individuals and of the collective staff. As such, this paper proposes to create a single entity within the university that encompasses development, government relations, communications, strategic planning, student, and alumni relations. Under traditional academic terminology, this Institutional Advancement Atelier would appear to be a ‘division’ of the university. However, under the new paradigm, arbitrary compartmentalization dissolves, and terms such as ‘division’ are no longer relevant.

The new organization works like this: most members of the Institutional Advancement Atelier will be housed in a single building to catalyze collaboration and creativity. This hub of communication must be located centrally on the campus and – in keeping with the studio tradition – workspace must be as open as possible to promote staff interaction, ingenuity and communication. Positive, enthusiastic and engaged communicators will typify the new organization; such behavior must be sought out and encouraged among employees. The building's layout and its relation to campus should encourage ‘chance encounters’ where individuals with various interests bump into one another as they circulate around, into and through the building.

The Atelier scheme reflects Lauer's (2006) recommendations for advancement to (a) work in participatory teams, (b) create an open learning environment, (c) study ideas from other cultures, and (d) evolve organizationally. Lauer describes the importance of staying positive at all times in order to inspire enthusiasm, and of overcoming the tendency to focus on ‘problem solving’ at the expense of opportunity seeking. He insists that too many organizations adopt a sour atmosphere and fail to celebrate positives.

Both Iarrobino (2006) and Lauer (2006) state that benefits accrue when there is flexibility for employees who ‘work hard’ to also ‘play hard.’ They each emphasize the importance of continually reiterating and celebrating the group's shared values and purpose/mission. Such behaviors prompt groups to proactively spot trends and seize opportunities in ways recommended by Cutright (2001), Presley and Leslie (1999), Rowley, Lujan, and Dolence (1998) and others.

Gordon et al (1993) note that collaboration can be difficult for those who lack trust, seek to protect their turf or are unwilling to share information with others. Building and maintaining trust are essential aspects of both emotional intelligence as defined by Goleman (2000) and authentic leadership as per Evans (2007). Leaders in this new Atelier must address resistance head-on to avoid problems in the long term (Kouzes and Posner, 1995; Fullan, 2001). Goleman indicates that to be most effective, leaders need to understand and apply a variety of different leadership styles. Leaders must adapt their responses to fit the specific situation as well as the orientations and motivations of the individuals involved.

LESS HIERARCHY, MORE COLLABORATION

The organizational chart proposed in Figure 1 implements a set of studios. Although each studio is dedicated to a specific advancement topic, individuals in each studio interact with other studios. Interaction must become much more fluid than is typical in university administration today. The proposed Atelier structure blends aspects the traditional design studio with traditional organizational distribution in a way that should be easily comprehendible to insiders and outsiders alike. The structure both differentiates and integrates advancement functions, as recommended by Gordon et al (1993). The proposal integrates titles and groupings that are common within today's university hierarchies, but nests these within a looser and less vertical/pyramidal structure.

The Atelier requires ‘leadership by teams’ as described by Bensimon (1993), who actually urges conceptualizing leadership teams as ‘cultures.’ Effective teams develop skill in thinking together. They strategically recruit diverse members who have relational and interpretive skills and who are dedicated to team-building and collective practice. The challenge for advancement leaders in the Atelier will be building ‘teams that think and act together; that see and sense, analyze and project, critique and reformulate; that strain to listen and understand inclusively; that reflect, in a critical spirit, on the work of their own hands’ (Bensimon, p. 146).

The collaborative Atelier structure will benefit from having leaders who view their role as facilitative. Numerous leadership theorists describe the exemplary outcomes of facilitative or ‘servant’ leaders who foster development by sharing authority and communicating ideals rather than simply exerting power over others (Bogue, 1994; Kouzes and Posner, 1995; Purpel, 2007; Sergiovanni, 2007).

ATELIER STRUCTURE

Within the university, the Institutional Advancement Atelier should be positioned at the same level as Academic Affairs, Student Affairs, Legal Affairs and Business Affairs. All of these divisions have the potential to be re-organized using a studio format, although the pressing need for creativity in Institutional Affairs supports the notion that it should be reformatted first.

As per Figure 1, the three major leaders of the Institutional Advancement Atelier each carry the traditional title of Associate Vice President (AVP). The three head the proposed Atelier and report directly to the president together. To support this notion, Lauer (2006) notes that new presidents often ‘want both a fund-raising professional and a marketing professional to report directly to them and to function as part of the executive leadership team’ (p. 185).

Each AVP in the Atelier will supervise and coordinate activities within two related studios. The AVP of Development Programs will coordinate activities of studios dedicated to (1) Development and (2) Government Relations. The Integrated Marketing AVP will head studios for (3) Communications and (4) Strategic Planning. Finally, the Student and Alumni Relations AVP will oversee studios for (5) Student Relations and (6) Alumni Relations.

This structure is akin to a large architectural firm with specialized design studios. Each studio nested within such a firm typically has a distinct concentration. A large architecture firm might house individual studios that specialize in historic preservation, educational or recreational buildings, health-care facilities, master planning for other entities, as well as its own strategic planning and marketing studio. Individual employees in such firms contribute most of their time to a single studio and to that studio's various project teams; however, individuals actively collaborate both within and across studios. Studios pool expertise and borrow or swap staff in response to changing needs and level of interest in a given project.

LEADERSHIP TRIAD

The structure shown in Figure 1 attempts to balance the three major functions within institutional advancement (that is fundraising, public relations and ‘past and present’ student relations). The structure of shared leadership attempts to create a more balanced approach than when (a) activities are segregated and compartmentalized under distinctly separate leaders, or (b) one single individual assumes a single Vice Presidency overseeing these various functions.

The triad structure of the Atelier helps overcome the difficulty Lauer (2006) identifies when just one individual (who has a limited set of strengths and concerns) serves as the sole Vice President of Advancement. In such a case, this individual often has trouble managing the vast array of advancement activities. With three people leading, the Atelier benefits from balanced expertise and diverse viewpoints.

Hall and Baker (2003) warn ‘that when there is a single vice-president for both [development and public relations], that vice-president may not have a public relations perspective and therefore the results are similar to subordinating public relations to marketing, human relations, or another function’ (p. 145). They report that while public relations (that is communications) may prosper under any number of structures, it must have substantial access to top leaders. Hall and Baker also state that public relations should coordinate and control all communications activities, and should be handled very strategically. As such, the proposed Atelier places the Communications Studio in direct relation to the Strategic Planning Studio (a studio that helps align the message all studios convey with the overall vision and direction of the university).

In the proposed Institutional Advancement Atelier, the three AVPs must collaborate to provide leadership and to construct and promote a collective vision. This leadership team needs ‘the creative imagination and drive to start up new ventures, formulate new programs, and anticipate needs before they appear to others’ (Lauer, 2006, p. 32). The Atelier requires collaboration at ‘the top’ as well as within and among studios. Every member of the Atelier must be willing and able to collaborate, to share workload and recognition, and to contribute his or her own unique talents and strengths in a way that complements and balances the overall effort. ‘Regardless of how divisions are organized,’ Lauer states, ‘organizational culture and management philosophy must ensure that units work together on developing both strategy and tactics’ to tap talent and energize groups (p. 189).

Baldridge et al (1977) describe the type of leadership necessary in ‘fluid’ conditions where ‘leaders serve primarily as catalysts or facilitators of an ongoing process. They do not so much lead the institution as channel its activities in subtle ways. They do not command but negotiate. They do not plan comprehensively, but try to apply preexisting solutions to problems’ (p. 131).

RECRUITING STRATEGIES

Creating a successful Atelier requires attracting and retaining a team of people who have the right behaviors, experience and knowledge. As not everyone will initially understand the studio format, it is critical to enlist individuals with experience in this type of work environment. People with studio experience must model collaboration and creative processes for others – especially for those used to working in isolation or accustomed to linear thinking. Graphic designers, marketing and advertising professionals, campus planners, and university architects all have experience with the studio format. These individual must be enlisted to foster studio collaboration and to provide grass roots leadership for the Atelier.

Iarrobino (2006) indicates that, unfortunately, many advancement operations today fail to ‘weed out those who do not fit’ (p. 148). Those in charge of screening and hiring tend to stress applicants’ immediate skills and/or direct experience in advancement, but often overlook essential characteristics including behavior, talent and knowledge that enable an applicant to excel in this high-turnover career. Care should be taken not to overlook creative, energetic individuals who simply lack experience working in advancement, an unfortunate trend that Iarrobino has documented.

Strategically hiring people who can work together and communicate well is essential – both to addressing current turnover problems and to successfully implementing the collaborative Atelier model. Iarrobino (2006) emphasizes that once a coherent shared vision has been developed, ‘it must be communicated throughout the staff frequently’ (p. 163).

SCHEDULING FOR EFFECTIVE COMMUNICATION

Kouzes and Posner (1995), Fullan (2001) and Iarrobino (2006) recommend holding regular forums to (a) reiterate the vision, (b) share ideas, (c) align activities, and (d) energize constituents. In the proposed scheme, the three AVPs would meet formally at least once each week to discuss overall vision, strategy and projects. As a team, the three of them would also meet with the university president once weekly, and all would serve together on the president's cabinet. These three AVPs would hold identical rank; they would rotate the role of point person for the Atelier on a 2-year basis.

To be effective, the three Advancement AVPs must foster connectivity within and among the various studios. They must encourage collaboration and exude confidence in the team's vision, direction and ability (Kouzes and Posner, 1995; Lauer, 2006). Each studio team will have specific expertise in the studio's concentration area, but all staff members must be encouraged to enlist advice and assistance from other studios and to offer ideas on projects throughout the Atelier. The Atelier will require wisdom, inspiration and entrepreneurship from its leaders. The AVPs must work with individuals in their specific studios to set clear performance measures. Each AVP ‘must be flexible and encourage participation in leadership’ (Sturgis, 2006, p. 225). Lauer (2006) indicates that this necessitates a departure from traditional management culture and style.

The Atelier will meet as a whole bimonthly, with individual studios convening at least once each week to discuss projects, strategy and alignment with the university's vision. Such a schedule is consistent with Iarrobino's (2006) recommendations for effective communication that include bimonthly staff meetings with the top advancement leaders and additional weekly or biweekly meetings within each department (that is studio). ‘The vice president[s] should seek agenda items from the staff and discuss them as a large group. … this style of meeting should work and increase collaboration at the same time as communication’ (Iarrobino, p. 164). It is important for staff to feel that praise, flexibility, options and rewards have been granted generously, fairly and consistently and that staff members are ‘safe and supported by superiors’ (p. 165). However, to ensure efficacy as well as sense of safety, performance standards must be determined and upheld.

MANAGERIAL APPROACHES

Hall and Baker (2003) note the importance of selecting a leadership team that balances historical-technical and strategic-managerial approaches. They indicate that advancement leaders must have adequate university support – including time and access to top administrators – and a culture that attends to key publics and to issues emerging in and around the university.

According to Morrill (2007), the type of supervision required within the Atelier could be aptly defined as ‘interactive leadership’ (p. 22). Leaders in this new organization must complement each other's talents and abilities. Morrill notes that good leaders must seek to integrate the four value sets that administrators typically use to see the world, instead of relying on just one or two sets. These involve the four major management styles defined by Bolman and Deal (2003): bureaucratic/administrative, political, collegial and symbolic. Bush and Coleman (2000) actually name six models, which they call bureaucratic, collegial, political, subjective, ambiguous and cultural. Similar to Morrill, they suggest a pluralist approach for enhanced decision-making.

As far back as 1977, Baldridge, Curtis, Ecker and Riley had already identified the three categories common to both these sets (bureaucratic, collegial and political), and had recommended adopting alternative models in higher education. Thirty years later, the issues Baldridge et al identified still help explain the complex nature and challenges of academia. Their list includes goal ambiguity, disparate client services, problematic technology, engrained professionalism, environmental vulnerability and organized anarchy.

Lauer (2006) insists that success in institutional advancement grows from within an organization and that it involves ‘the right product(s),’ a strong sense of identity, and sophisticated approaches to marketing. He defines sophisticated marketing as

Seeing the world as market segments, thinking strategically about ways to connect them, appreciating the power of imaginative writing and creative design, realizing that special events are optimal communication opportunities, understanding the news media are changing and are no longer reliable, and knowing that out-front leadership is the make-or-break factor.

He indicates that

The sad truth is that few institutions have enough talented people who think and act this way. And when these talented people are present, they are often taken for granted or rejected because they threaten the traditional ways of thinking. (p. 214)

INTEGRATED APPROACHES TO FUNDRAISING AND MARKETING

Similar to Lauer (2006), Boverini (2006) indicates that securing funds from newly emerging high-impact donors (otherwise known as venture philanthropists) requires a range of creative response mechanisms. Collaborative teams within the Atelier will be better equipped than today's isolated units to address this need identified by Boverini. Collaboration can help prepare ‘development officers, who are often used to being the idea generators,’ as Boverini indicates that they will now ‘have to become the idea processors, possessing the ability to craft a solution to fulfill what the venture philanthropist determines as a perceived need for the institution’ (p. 98). One of the ultimate goals of the Atelier structure is ‘to promote professionalism, stability, and confidence to potential donors’ (Iarrobino, 2006, p. 144).

A former university president, Bornstein (2003) emphasizes the importance of shared leadership and collaboration. She promotes techniques for integrating fundraising with other administrative efforts, as is inherent in the proposed Atelier. The Atelier integrates all four of the conceptual shifts that Bornstein says

must occur in order to assure the legitimacy of fund-raising: (1) fund-raising must be viewed as partnering, not begging; (2) fund-raising must move from the periphery to the center of the academy; (3) fund-raising must be integrated and seamless with other administrative functions, not discrete and disconnected; and (4) fund-raising must assure ethical practices that benefit both the donor and the institution, rather than employing self-serving practices. (p. 126, emphasis added)

CONCLUSION

Institutional advancement professionals can and must develop better and more proactive ways to handle operations and enhance their educational communities. This requires confronting existing problems in advancement such as (a) oppressive bureaucracy, (b) extensive compartmentalization, and (c) unsuccessful recruiting and retention. By enhancing its own organizational efficacy, institutional advancement will be better able to face inevitable demands for higher levels of (a) public accountability, (b) fund-raising and donor cultivation, (c) ethical standards for conduct and reporting, and (d) proactive environmental scanning. Using organizational structures that are typically associated with creative design professions makes clear sense. Design techniques and strategies lend themselves to developing and communicating coherent plans. The studio is a viable means for pooling talent and resources and for promoting non-linear, creative and collaborative thinking.

The proposed Institutional Advancement Atelier helps align advancement efforts within a university to more effectively support the university's overarching mission. The proposed Atelier will cultivate a range of skills and connect them in imaginative and proactive ways. Using an integrated studio format will allow the Atelier to successfully and gracefully address pressure ‘to raise much more money, mobilize all their alumni, communicate more effectively what ‘higher education’ is all about, and recruit more competitively for the talented and imaginative students who will save our world’ (Lauer, 2006, p. 14). Using the studio metaphor, the Institutional Advancement Atelier can achieve the future that Lauer foresees, where ‘the whole idea of institutional marketing in its best and most comprehensive form will come solidly into its own.’

References

Baldridge, J.V., Curtis, D.V., Ecker, G.P. and Riley, G.L. (1977) Alternative models of governance in higher education. In: M.C. Brown (ed.) Organization and Governance in Higher Education. Boston, MA: Pearson, pp. 128–142.

Bensimon, E.M. (1993) Redesigning Collegiate Leadership: Teams and Teamwork in Higher Education. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press.

Bess, J.L. and Dee, J.R. (2008) Understanding College and University Organization: Theories for Effective Policy and Practice, Vol. II. Sterling, VA: Stylus.

Birnbaum, R. (1988) How Colleges Work: The Cybernetics of Academic Organization and Leadership. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Bogue, E.G. (1994) Leadership by Design: Strengthening Integrity in Higher Education. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Bolman, L.G. and Deal, T.E. (2003) Reframing Organizations. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Bornstein, R. (2003) Legitimacy in the Academic Presidency: From Entrance to Exit. Westport, CT: Praeger.

Boverini, L. (2006) When venture philanthropy rocks the ivory tower. International Journal of Educational Advancement 6 (2): 84–106.

Bush, T. and Coleman, M. (2000) Leadership and Strategic Management in Education. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Chaffee, E.E. (1985) Three models of strategy. Academy of Management Review 10: 89–98.

Chapman, J. (1993) Leadership, school-based decision making and school effectiveness. In: C. Dimmock (ed.) School based management and School Effectiveness. London: Routledge, pp. 201–208.

Coulter, S. (2008) Institutional advancement organization, http://www.uth.tmc.edu/factbook/2008/university/orgchart.html, accessed 4 July 2008.

Cutright, M. (ed.) (2001) Introduction: Metaphor, chaos theory, and this book. Chaos Theoryand Higher Education: Leadership, Planning, and Policy. Baltimore, MD: Peter Lang, pp. 1–11.

Evans, R. (2007) The authentic leader. The Jossey-Bass Reader on Educational Leadership, 2nd edn. San Francisco, CA: John Wiley and Sons, pp. 135–158.

Fullan, M. (2001) Leading in a Culture of Change. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Goleman, D. (2000) Leadership that gets results. Harvard Business Review 78 (2): 78–90.

Gordon, S.E., Strode, C.B. and Brady, R.M. (Fall 1993) Student affairs and educational fundraising: The critical first step. In: M.C. Terrell and J.A. Gold (eds.) New Directions for Student Services, Vol. 63. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass, pp. 5–16.

Hall, M.R. and Baker, G.F. (2003) Public relations from the ivory tower: Comparing research universities with corporate/business models. International Journal of Educational Advancement 4 (2): 127–154.

Iarrobino, J.D. (2006) Turnover in the advancement profession. International Journal of Educational Advancement 6 (2): 141–169.

James Madison University Office of Human Resources. (n.d.) Managers’ organizational chart, http://www.jmu.edu/humanresources/hrsc/orgchart.shtml, accessed 4 July 2008.

Kouzes, J.M. and Posner, B.Z. (1995) The Leadership Challenge. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Kunstler, B. (2005) The hothouse effect: A model for change in higher education. On the Horizon 13 (3): 173–181.

Larsen, P.V. (2003) Academic reputation: How U.S. News & World Report Survey respondents form perceptions. International Journal of Educational Advancement 4 (2): 155–165.

Lauer, L. (2006) Advancing Higher Education in Uncertain Times. Washington, DC: Council for Advancement and Support of Education.

Magsaysay, J. (1997) Managing in the 21st century. World Executive's Digest, January pp. 18–22.

Mieczkowski, B. (1995) The Rot at the Top: Dysfunctional Bureaucracy in Academia. Lanham, MD: University Press of America.

Morrill, R.L. (2007) Strategic Leadership: Integrating Strategy and Leadership in Colleges and Universities. Westport, CT: Praeger.

Mortimer, K.P. and Sathe, C.O. (2007) The Art and Politics of Academic Governance: Relations Among Boards, Presidents, and Faculty. Westport, CT: Praeger.

Nichols State University. (2007) Institutional advancement organization chart, http://www.goldenwestcollege.edu/administration/GWCOrgChart2006-07.pdf, accessed 4 July 2008.

North Carolina State University. (2007) Organization chart of North Carolina State University, http://www2.acs.ncsu.edu/UPA/uniorgchart/chart.pdf, accessed 4 July 2008.

Old Dominion University. (2008) Old Dominion University, http://www.odu.edu/af/pressearch/org_chart.pdf, accessed 4 July 2008.

Presley, J.B. and Leslie, D.W. (1999) Understanding strategy: An assessment of theory and practice. In: J.C. Smart and W.G. Tierney (eds.) Higher Education: Handbook of Theory and Research, Vol. 14. Bronx, NY: Agathon Press, pp. 201–239.

Purpel, D.E. (2007) An educational credo for a time of crisis and urgency. The Jossey-Bass Reader on Educational Leadership, 2nd edn. San Francisco, CA: John Wiley and Sons, pp. 93–98.

Rowley, D.J., Lujan, H.D. and Dolence, M.G. (1997) Strategic Change in Colleges and Universities: Planning to Survive and Prosper. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Rowley, D.J., Lujan, H.D. and Dolence, M.G. (1998) Strategic Choices for the Academy: How Demand for Lifelong Learning will Re-create Higher Education. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Sergiovanni, T.J. (2007) Leadership as stewardship: ‘Who's serving who?’. The Jossey-Bass Reader on Educational Leadership, 2nd edn. San Francisco, CA: John Wiley and Sons, pp. 75–92.

Shahjahan, R.A. (2005) Spirituality in the academy: Reclaiming from the margins and evoking a transformative way of knowing the world. International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education 18 (6): 685–711.

Siena Heights University. (2007) Institutional advancement division, http://list.case.org/cgi-bin/wa.exe?A3=ind0710&L=ADVANCE-L&E=base64&P=3430124&B=--_002_ B1EBF27DF5B5F74BABFBC52468094691863863017Ctritonsienaht_&T=application%2Fvnd.ms-powerpoint;%20name=%22Advancement%20org%20chart%209.07.ppt%22&N=Advancement%20org%20chart%209.07.ppt&attachment=q, accessed 4 July 2008.

Sturgis, R. (2006) Presidential leadership in institutional advancement: From the perspective of the president and vice president of institutional advancement. International Journal of Educational Advancement 6 (3): 221–231.

Swenk, J.P. (2001) Strategic planning and chaos theory: Are they compatible? In: M. Cutright (ed.) Chaos Theory and Higher Education: Leadership, Planning, and Policy. Baltimore, MD: Peter Lang, pp. 33–56.

University of Tennessee at Martin. (n.d.) SACS accreditation office self study report, http://www.utm.edu/organizations/sacs/Introduction.doc, accessed 4 July 2008.

Wilson, D. (1997) Project monitoring: A newer component of the educational planning process. Educational Planning 11 (1): 31–40.

Acknowledgements

This paper was submitted in partial completion of a course on Institutional Advancement conducted by Karlene Jennings, PhD, CFRE, Director of Development at the Earl Gregg Swem Library of the College of William and Mary.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Chance, S. Proposal for using a studio format to enhance institutional advancement. Int J Educ Adv 8, 111–125 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1057/ijea.2009.8

Received:

Revised:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/ijea.2009.8