Abstract

Phosphopantetheinyl transferases (PPTases) play essential roles in both primary metabolisms and secondary metabolisms via post-translational modification of acyl carrier proteins (ACPs) and peptidyl carrier proteins (PCPs). In this study, an industrial FK506 producing strain Streptomyces tsukubaensis L19, together with Streptomyces avermitilis, was identified to contain the highest number (five) of discrete PPTases known among any species thus far examined. Characterization of the five PPTases in S. tsukubaensis L19 unveiled that stw ACP, an ACP in a type II PKS, was phosphopantetheinylated by three PPTases FKPPT1, FKPPT3 and FKACPS; sts FAS ACP, the ACP in fatty acid synthase (FAS), was phosphopantetheinylated by three PPTases FKPPT2, FKPPT3 and FKACPS; TcsA-ACP, an ACP involved in FK506 biosynthesis, was phosphopantetheinylated by two PPTases FKPPT3 and FKACPS; FkbP-PCP, an PCP involved in FK506 biosynthesis, was phosphopantetheinylated by all of these five PPTases FKPPT1-4 and FKACPS. Our results here indicate that the functions of these PPTases complement each other for ACPs/PCPs substrates, suggesting a complicate phosphopantetheinylation network in S. tsukubaensis L19. Engineering of these PPTases in S. tsukubaensis L19 resulted in a mutant strain that can improve FK506 production.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

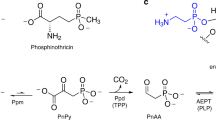

Phosphopantetheinyl transferases (PPTases) catalyze the phosphopantetheinylation of acyl carrier proteins (ACPs) in polyketide synthases (PKSs), peptidyl carrier proteins (PCPs) in nonribosomal peptide synthetases (NRPSs) and ACPs in fatty acid synthases (FASs) from inactive apo-forms into active holo-forms1,2,3. Thus, PPTases are essential to both primary metabolisms and secondary metabolisms in various species. PPTases can be classified into three groups according to their structures. A group I PPTase, also named as an ACPS-type PPTase, consists of three identical peptide subunits with about 120 amino acid residues in each subunit4,5,6. A group II PPTase, also named as a Sfp-type PPTase, consists of one peptide which is about twice the size of one group I PPTase subunit7,8,9. A group III PPTase exists as a domain of a FAS or a PKS10,11.

A group III PPTase prefers to phosphopantetheinylate the ACP, which locates with it in the same peptide10,11. A discrete PPTase, a group I PPTase or a group II PPTase, should phosphopantetheinylate multiple ACPs/PCPs, since the number of PPTases is much less than that of ACPs/PCPs in all known species 12,13,14,15. Animals and Plants usually contain one to three group II PPTases16. Few bacteria harbor only one group II PPTase which phosphopantetheinylate ACPs/PCPs involved in both primary metabolism and secondary metabolism, such as Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Nodularia spumigena NSOR10, Synechocystis sp. PCC6803 and Haemophilus influenza17,18,19,20. Most bacteria have one group I PPTase and no less than one group II PPTases12,13,14,15. In Streptomyces coelicolor and Streptomyces chattanoogensis L10, it has been reported that group I PPTases prefer to phosphopantetheinylate ACPs in type II FASs and type II PKSs, while group II PPTases prefer to phosphopantetheinylate ACPs in type I PKSs12,13. Recently, antibiotic production has been improved by engineering of PPTases13.

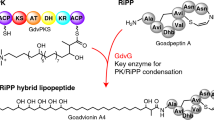

FK506 (tacrolimus) is a clinical immunosuppressant widely used after allogeneic kidney, liver and heart transplantations21,22,23,24. Industrial production of FK506 is made by fermentation of some Streptomyces strains. Although FK506 is known to be biosynthesized by a PKS/NRPS hybrid and partial biosynthetic pathway of FK506 has been elucidated25,26,27,28, phosphopantetheinylation of ACPs/PCPs in FK506 biosynthetic PKS/NRPS has never been studied to date. An FK506 producing strain, Streptomyces tsukubaensis L19 was isolated from Yunnan, China by our group and was used for industrial production of FK506. In this study, we identified one group I PPTase and four group II PPTases in an industrial FK506 producing strain S. tsukubaensis L19. Characterization of these PPTases unveiled that the functions of these PPTases complement each other, suggesting a complicate phosphopantetheinylation network in S. tsukubaensis L19. A mutant strain with higher FK506 production and shorter fermentation time was also constructed by engineering of these PPTases.

Results and Discussion

Analysis of discrete PPTase genes and PKS gene clusters in Streptomyces tsukubaensis L19

The whole genomic DNA of S. tsukubaensis L19 was recently sequenced to contain more than 7.9 M base pairs and 7,000 open reading frames (ORFs). Analysis of the genomic sequence revealed five discrete PPTase genes, FKPPT1, FKPPT2, FKPPT3, FKPPT4 and FKACPS (GenBank accession numbers KT582112-KT582116). Neither of these genes is clustered with any secondary metabolite biosynthesis gene clusters. Alignment of these PPTases with known PPTases showed that FKPPT1, FKPPT2, FKPPT3, FKPPT4 contains three conserved motifs, PRWP, GID and FSAKESVYK, found in the Sfp-type PPTase motifs P1, P2 and P3, while FKACPS contains just last two conserved motifs found in ACPS-type PPTase. Thus, FKPPT1, FKPPT2, FKPPT3 and FKPPT4 belong to the Sfp-type PPTase group and FKACPS belongs to the ACPS-type PPTase group, respectively (Fig. 1).

Sequence alignment of group II PPTases (A) and group I PPTases (B). Conserved motifs P1, P2 and P3 are indicated. The proposed magnesium binding residues are shaded. svp (GenBank accession Nos AAG43513), SchPPT (JQ283111), SCO6673 (NP_630748), SePptII (A4FC68), sfp (BAA09125), SchACPS (JQ283112), SCO4744 (OO86785), EcACPS (P24224), BsACPS (CAB12269), SpACPS (AAG22706).

Most bacteria contain two to three discrete PPTases, such as E. coli, S. coelicolor, S. chattanoogensis L1012,13. To date, Streptomyces avermitilis is the known to harbor the highest number (five) of discrete PPTases1,29. Together with S. avermitilis, S. tsukubaensis L19 contains the highest number of discrete PPTases known among any species thus far examined.

Analysis of the genomic sequence of S. tsukubaensis L19 revealed about thirty proposed PKS, NRPS and PKS-NRPS hybrid gene clusters. The FK506 biosynthetic gene cluster in S. tsukubaensis L19 showed 100% DNA identity with that in Streptomyces tsukubaensis YN0627,28. A type II PKS was named as stw PKS (Streptomyces tsukubaensis whiE), since its gene cluster contains homologous genes in whiE PKS gene clusters, which are involved in spore pigment biosynthesis in several Streptomyces strains (Fig. 2)30,31,32. More than one hundred proposed ACPs and PCPs within these PKSs, NRPSs and PKS-NRPS hybrids were potential substrates of these five PPTases.

In vitro phosphopantetheinylation system

To characterize if these five PPTases have activities, an in vitro co-expression system was built up. TcsA-ACP (the ACP domain in the allylmalonyl unit biosynthetic module in FK506 biosynthetic PKS/NRPS), FkbP-PCP (the PCP domain in the NRPS module in FK506 biosynthetic PKS/NRPS), stw ACP (the ACP in stw PKS) and sts FAS ACP (the ACP in S. tsukubaensis L19 FAS) were selected as substrates of PPTases. First, tcsA-ACP, fkbP-PCP (fused with SUMO gene), stw ACP and sts FAS ACP were individually cloned into pET28a, resulting in four ACP/PCP-containing-plasmids pET-AACP, pYY0081, pYY0082 and pYY0098, respectively. Second, FKPPT1, FKPPT2, FKPPT3, FKPPT4 and FKACPS were individually cloned into the NdeI/HindIII sites of pYY004016, in which both His-tag gene and Nus-tag genes were deleted from pET44a, resulting in five PPTase-containing-plasmids, pYY0072, pYY0078, pYY0073, pYY0077 and pYY0074, respectively. Finally, four E. coli BL21(DE3) harboring both an ACP/PCP-containing-plasmid and pYY0040 were induced with IPTG to overproduce His-tagged ACPs/PCP. Twenty E. coli strains harboring both an ACP/PCP-containing-plasmid and a PPTase-containing-plasmid were induced with IPTG to overproduce His-tagged ACPs/PCP with intact PPTases. His-tagged ACPs/PCP were then purified to homogeneity by affinity chromatograph.

Phosphopantetheinylation of the ACP/PCP involved in FK506 biosynthesis

Regarding TcsA-ACP, when tcsA-ACP was co-expressed with pYY0040 in E. coli, HPLC data showed that purified TcsA-ACP were eluted as two peaks with the area ratio of the small peak with shorter retention time and the large peak with longer retention time as 0.67. MS data revealed that the large peak represented apo-proteins and the small peak represented holo-proteins, indicating that E. coli ACPS could convert it from the apo-form to holo-form incompletely. After co-expression of tcsA-ACP with FKPPT3 or FKACPS, all purified TcsA-ACP were holo-form by HPLC analysis. While co-expression of tcsA-ACP with FKPPT1, FKPPT2 or FKPPT4, the ratio of the apo-form and the holo-form did not change compared with co-expression of it with pYY0040 (Fig. 3A). These results indicated that FKPPT3 and FKACPS could phosphopantetheinylate TcsA-ACP, but FKPPT1, FKPPT2 and FKPPT4 could not under these conditions.

HPLC analyses of TcsA-ACP (A), stw ACP (B) and sts FAS ACP (C). Each of ACP genes was cloned into pET28a. Each of PPTase genes was cloned into pYY0040, a plasmid derived from pET44a. E. coli strains harboring both a ACP-containing-plasmid and a PPTase-containing-plasmid were induced with IPTG to produce His-tagged ACPs with intact PPTases. His-tagged ACPs were purified by affinity chromatograph and then analyzed by HPLC and MS. ▽, apo-form; ▼, holo-form.

Regarding FkbP-PCP (fused with SUMO protein), when FkbP-PCP (fused with SUMO gene) was co-expressed with pYY0040 in E. coli, HPLC data showed that purified FkbP-PCP were eluted as a single peak. MS analysis showed that this peak represented both apo-proteins and holo-proteins with the ratio of the peak height of holo-proteins and the peak height of apo-proteins as about 0.40. After co-expression of FkbP-PCP with each of PPTase genes, HPLC data showed that purified FkbP-PCP were still eluted as a single peak. While co-expression of FkbP-PCP with FKPPT1 and FKPPT2, MS data showed that the ratio of the peak height of holo-proteins and the peak height of apo-proteins increased significantly to 2.58 and 2.34, respectively. While co-expression of FkbP-PCP with FKPPT3, FKPPT4 and FKACPS, MS data showed that only the peak of holo-proteins remained but the peak of apo-proteins disappeared (Fig. 4). These results supported that all of these five PPTases could phosphopantetheinylate FkbP-PCP.

MS analyses of FkbP-PCP.

FkbP-PCP gene fused with SUMO gene was cloned into pET28a. Each of PPTase genes was cloned into pYY0040. E. coli strains harboring both a PCP-containing-plasmid and a PPTase-containing-plasmid were induced with IPTG to produce His-tagged PCPs with intact PPTases. His-tagged PCPs were purified by affinity chromatograph and then analyzed by HPLC and MS. The calculated molecular weights of apo-form and holo-form of FkbP-PCP is 26,970 Da and 27,310 Da, respectively.

Phosphopantetheinylation of the ACP in a type II PKS

When stw ACP was co-expressed with pYY0040 in E. coli, HPLC data showed that purified stw ACP were eluted as a single peak, which represented apo-proteins by MS analysis. After co-expression of stw ACP with FKPPT1, FKPPT3, or FKACPS, a new peak, whose area is about 21%, 20% and 34% of that of apo-proteins respectively, with shorter retention time compared with that of apo-proteins appeared in HPLC data, which represented holo-proteins by MS analysis. After co-expression of stw ACP with FKPPT2 or FKPPT4, HPLC data didn’t show any holo-proteins (Fig. 3B). These results suggested that stw ACP could be phosphopantetheinylated by FKPPT1, FKPPT3 and FKACPS but not FKPPT2 and FKPPT4.

Phosphopantetheinylation of the ACP in FAS

When sts FAS ACP was co-expressed with pYY0040 in E. coli, HPLC data showed that purified sts FAS ACP were eluted as two peaks with the area ratio of the peak with shorter retention time and the peak with longer retention time as 1.20. MS data revealed that the peak with longer retention time represented apo-proteins and the peak with shorter retention time represented holo-proteins. After co-expression of sts FAS ACP with FKPPT2, FKPPT3, or FKACPS, the ratio of holo-proteins and apo-proteins increased significantly to about 2.93, 2.17 and 1.67, respectively. While co-expression of sts FAS ACP with FKPPT4, this ratio almost did not change (about 1.01). Surprisingly, while co-expression of sts FAS ACP with FKPPT1, this ratio decreased significantly to about 0.28 (Fig. 3C). These results supported that FKPPT2, FKPPT3 and FKACPS could phosphopantetheinylate sts FAS ACP, but FKPPT1 and FKPPT4 could not.

The above results strongly supported that these five PPTases are indeed PPTases. Their functions should complement each other since each of ACPs/PCP could be phosphopantetheinylated by more than one PPTases, suggesting a complicate phosphopantetheinylation network in S. tsukubaensis L19 (Fig. 5). PCP could be phosphopantetheinylated by all five PPTases, suggesting that the flexibility to PPTases of PCP is more than that of ACPs.

Inactivation of FKPPT1 or FKPPT3 decreased the FK506 yield in S. tsukubaensis L19

To determine the influence of the activities of the group II PPTases on FK506 production in vivo, FKPPT1, FKPPT2, FKPPT3 and FKPPT4 were individually replaced with the apramycin resistance gene aac(3)IV in S. tsukubaensis L19 by using Redirect technology, resulting in four mutant strains sHJ0015-sHJ0018, respectively. Each of mutant strains sHJ0015-sHJ0018 was fermented in triplicate fermentation medium in flasks for 72 h by using S. tsukubaensis L19 as control. FK506 production was monitored by HPLC analyses. The FK506 yields of sHJ0015 (ΔFKPPT1) and sHJ0017 (ΔFKPPT3) decreased ~33% and ~22% compared to that of S. tsukubaensis L19, respectively, suggesting that FKPPT1 and FKPPT3 play important roles in the FK506 biosynthesis. The FK506 yields of sHJ0016 (ΔFKPPT2) and sHJ0018 (ΔFKPPT4) had no obvious change compared to that of S. tsukubaensis L19, supporting that lack of FKPPT2 and FKPPT4 in the biosynthesis of FK506 could be complemented by other PPTases (Fig. 6A).

FK506 production of S. tsukubaensis L19 and its recombinant strains in flasks (A) and fermentors (B). A. Each strain was fermented in triplicate fermentation medium in flasks for 72 h. B. Each strain was fermented in triplicate fermentation medium in 100 L fermentors under rigorously identical conditions. sHJ0015, deletion of FKPPT1 in S. tsukubaensis L19; sHJ0016; deletion of FKPPT2 in S. tsukubaensis L19; sHJ0017, deletion of FKPPT3 in S. tsukubaensis L19; sHJ0018, deletion of FKPPT4 in S. tsukubaensis L19; sHJ0019, overexpression of FKPPT1 in S. tsukubaensis L19; sHJ0020, overexpression of FKPPT2 in S. tsukubaensis L19; sHJ0021, Overexpression of FKPPT3 in S. tsukubaensis L19; sHJ0022, overexpression of FKPPT4 in S. tsukubaensis L19.

The above in vivo results showed that none of these four group II PPTases is indispensable to the FK506 biosynthesis. These results are consistent with the in vitro results that FK506 biosynthetic ACP and PCP could be phosphopantetheinylated by more than one PPTases.

Overexpression of FKPPT3 increased the FK506 production and decreased the fermentation time in S. tsukubaensis L19

To study the effect of the expression level of the group II PPTase genes on FK506 production, four PPTase gene overexpression mutant strains were constructed. FKPPT1, FKPPT2, FKPPT3 and FKPPT4 under the control of a strong promoter ermEp* were individually introduced into S. tsukubaensis L19, resulting in four PPTase gene overexpression mutant strains sHJ0019-22, respectively. Each of mutant strains sHJ0019-sHJ0022 in triplicate cultures was fermented in flasks for 72 h by using S. tsukubaensis L19 as control. The FK506 yields of sHJ0020 (ermEp*-FKPPT2) and sHJ0022 (ermEp*-FKPPT4) had no obvious change compared to that of S. tsukubaensis L19, suggesting again that neither FKPPT2 nor FKPPT4 is crucial to the FK506 biosynthesis. However, the FK506 yields of sHJ0019 (ermEp*-FKPPT1) and sHJ0021 (ermEp*-FKPPT3) increased ~20% and ~25% compared to that of S. tsukubaensis L19, respectively, supporting again that FKPPT1 and FKPPT3 play important roles in FK506 biosynthesis (Fig. 6A). To confirm sHJ0019 (ermEp*-FKPPT1) and sHJ0021 (ermEp*-FKPPT3) enhance the abilities of FK506 production, these two strains were fermented in triplicate fermentation medium in 100 L fermentors under rigorously identical conditions by using S. tsukubaensis L19 as control. The curve of FK506 production in S. tsukubaensis L19 showed that the FK506 yield reached the highest level at 154 ± 34 mg/L at 72 h. Notably, the FK506 yields of sHJ0019 (ermEp*-FKPPT1) and sHJ0021 (ermEp*-FKPPT3) reached the highest level at 171 ± 17 mg/L at 72 h and 183 ± 13 mg/L at 48 h, respectively (Fig. 6B). Thus, sHJ0021 (ermEp*-FKPPT3) not only increased FK506 production by ~19% but also decreased the fermentation time by 24 h in the fermentor scale fermentation, which may be beneficial for the industrial FK506 production. Strain sHJ0021 was deposited in China General Microbiological Culture Collection Center (CGMCC) as name Streptomyces tsukubaensis L20 with CGMCC number 11252. Additionally, All of eight mutant strains didn’t show obvious morphological different comparing with S. tsukubaensis L19 during growth in solid media and liquid media, including sporulation, cell color and the length of mycelium.

In summary, we identified that S. tsukubaensis L19 contains five discrete PPTases. Characterization of these PPTases showed that their functions complement each other, suggesting a complicate phosphopantetheinylation network in S. tsukubaensis L19. We also provided an example to improve the antibiotic production by engineering of PPTases.

Methods

Bacterial Strains, Plasmids, growth and culture conditions

Bacterial strains and plasmids used in the present study are listed in Table 1 and primers are listed in Table 2. The spore preparation of Streptomyces tsukubaensis L19 was done on ISP4 agar after 10 days at 26 °C. DNA manipulations in S. tsukubaensis L19 and E. coli-S. tsukubaensis L19 conjugation were carried out according to standard procedures33.

Fermentation of S. tsukubaensis L19 and its recombinant strains

S. tsukubaensis L19 and its recombinant strains were cultured on ISP4 agar at 26 °C for 7 days. Five full colonies were inoculated into 50 mL seed medium [1% (w/v) glycerol, 1% maltodextrin, 4% soybean meal, 0.2% CaCO3, pH 6.8] in 250 mL flasks and cultured at 28 °C, 220 rpm for 24–30 h. For fermentation of strains in flasks, the 2.5 mL of seed cultures were inoculated into 25 mL of fermentation medium (5% maltodextrin, 1% yeast extract, 3% cotton seed meal, 0.2% K2HPO4, 0.1% CaCO3, pH 6.8) and grown at 28 °C, 220 rpm for 5 days.

For fermentation of strains in fermentors, the 20 mL of seed cultures were inoculated into 10 L of seed medium containing 0.03% defoamer in 20 L fermentors and grown at 28 °C for 1 day. Then the 6 L of secondary seed cultures were inoculated into 60 L of fermentation medium containing 0.2% defoamer in 100 L fermentors and grown at 28 °C for 5 days. Fermentor cultivations were carried out by using the same bioreactor system with pH, pO2 and temperature control. All flask and fermentor experiments were performed at least triplicates.

Analysis of FK506 production

To assay for FK506 production in the culture broths, a sample was withdrawn and ultrasonic extracted with the same volume of methanol. Methanol layer was recovered by centrifugation at 12,000 rpm for 15 min. The concentration of FK506 was determined using an HPLC system (Agilent Series 1100, Agilent) equipped with a SB-C18 column (150 × 2.1 mm, Agilent). The column temperature was maintained at 60 °C and UV detector was set at 215 nm. The mobile phase, which had a flow rate of 1.0 mL/min, contained 0.02 M KH2PO4 (pH 3.5) solution and acetonitrile in the ratio of 40:60.

Genome sequencing and genome annotation

The nucleotide sequence of S. tsukubaensis L19 genome was determined by using a massively parallel pyrosequencing technology (Roche 454 GS FLX). 160 contigs (>500 bp) with a total size of 9.0 Mb were assembled from 522,882 reads (average length of 437 bp) using Newbler software of the 454-suite package, providing a 25.3-fold coverage. The relationship among contigs was determined by using multiplex PCR. Gaps were filled by sequencing PCR products. The final sequence assembly was performed using phred/phrap/consed package (http://www.phrap.org/phredphrapconsed.html) and the low sequence quality region was re-sequenced.

Putative protein-coding sequences were determined by combining the prediction results of glimmer 3.0234 and Z-Curve program35. Functional annotation of CDS was performed by searching the NCBI non-redundant protein database and KEGG protein database. Protein domain prediction and COG assignment were performed by RPS-BLAST using NCBI CDD library36.

Production and purification of ACPs/PCP

The three ACP genes were amplified by PCR using relevant primers from genomic DNA of S. tsukubaensis L19. The resultant products were cloned into pTA2 vector (Toyobo) directly and sequenced to confirm PCR fidelity. Then these genes were digested with NdeI/HindIII and cloned into the same sites of pET28a (Novagen), yielding three ACP-containing-plasmids pET-AACP and pYY0081-pYY0082, respectively. And the PCP gene was cloned into the pET28a-SUMO (Novagen), resulting in a PCP-containing-plasmid pYY0098. Finally, these plasmids were introduced into E. coli BL21(DE3) to overproduce proteins as N-His6-tagged protein. The ACPs were overproduced under standard conditions. BL21(DE3) harboring each expression plasmid were grown in LB medium with kanamycin at 37 °C until OD600 reached 0.4. Then IPTG was added to the final concentration of 0.4 mM and incubation continued at 37 °C for 4 h, resulting in overproduction of proteins in soluble form with good yield.

Purification of these proteins by affinity chromatography on Ni-NTA agarose (Qiagen) was performed under standard conditions recommended by the manufacturer. The proteins were dialyzed against 20 mM Tris·HCl (pH 8.0), 25 mM NaCl, 1 mM DTT and 10% glycerol.

Co-expression of ACP/PCP genes with PPTase genes

The five PPTase genes were amplified by PCR using relevant primers from genomic DNA of S. tsukubaensis L19. The resultant products were cloned into pTA2 vector directly and sequenced to confirm PCR fidelity. Then these genes were digested with NdeI/HindIII and cloned into the same sites of pET44a (Novagen), yielding five PPTase-containing-plasmids pYY0072-pYY0074 and pYY0077-pYY0078, respectively. BL21(DE3) harboring both each of ACP/PCP-containing-plasmids and each of PPTase-containing-plasmids were grown in LB medium with both kanamycin and ampicillin at 37 °C until OD600 reached 0.4. Then IPTG was added to the final concentration of 0.4 mM and incubation continued at 37 °C for 4 h. Purification and dialysis of ACPs/PCP was performed as same as described before.

HPLC analyses of ACPs

The ACPs produced from E. coli or from the phosphopantetheinylation reaction mixture were directly analyzed by HPLC (LC-20AT, Shimadzu). HPLC separation was carried out on a C18 column (Zorbax, 300SB-C18, 5 μm, 4.6 × 250 mm, Agilent). Solvent A consisted of 0.1% formic acid. Solvent B consisted of acetonitrile. The following binary gradient was used: 0–15 min, a linear gradient from 0% to 75% B; 15–16 min, a linear gradient from 75% to 100% B; 16–19 min, 100% B; 19–20 min, a linear gradient from 100% to 0% B; 20–24 min, 0% B at a flow rate of 1 ml/min. UV detection was performed at 220 nm (SPD-20A, Shimadzu).

LC-MS analyses of ACPs/PCP

The ACPs produced from E. coli or from the phosphopantetheinylation reaction mixture were directly analyzed by LC-MS (Agilent 1200, Thermo Finnigan LCQ Deca XP MAX). LC separation was carried out on a Agilent SB-C18 column (3.5 μm, 80 Å, 2.1 × 150 mm, Agilent) at 35 °C. Solvent A consisted of 0.1% formic acid. Solvent B consisted of acetonitrile. The following binary gradient was used: 0–5 min, 5% B; 5–45 min, a linear gradient to 75% B; followed by 3 min isocratic elution of 75% B and equilibrated to initial condition for 13 min at a flow rate of 0.2 ml/min. UV detection was performed at both 254 nm and 280 nm. MS equipped with ESI source was performed as follows: positive; source voltage, 2.5 kV; capillary voltage, 41 V; sheath gas flow, 45 arb; aux/sweep gas flow, 5 arb; capillary temperature, 330 °C.

Construction of PPTase:aac3(IV) mutant strains

The PPTase gene disruption mutant was constructed by using a modified PCR targeting system as follows37. First, four cosmids, which contain each of FKPPT1, FKPPT2, FKPPT3 and FKPPT4, were screened out by PCR amplification. Second, each disruption cassette aac(3)IV (Apra) was PCR amplified from pHY773 (Z. Qin, Institute of Plant Physiology and Ecology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Shanghai, China, unpublished results), with the resulting product carrying 59 bp ends with homology to the corresponding region of PPTase gene. Each PCR product was then introduced into E. coli BW25113 carrying pIJ790/cosmid and transformed cells carrying mutagenized cosmid were selected on LB agar containing apramycin. Each mutagenized cosmid, in which a PPTase gene was replaced with aac(3)IV, was confirmed by PCR analysis using primers accordingly. Third, after conjugal transfer of each mutagenized cosmid from E. coli ET12567 carrying pUZ8002 into S. tsukubaensis L19, exconjugants were obtained after selection for apramycin resistance. Exconjugants were then inoculated onto ISP4 plates for two rounds of nonselective growth before selection by replica plating for thiostrepton-sensitive and apramycin-resistant colonies. Each resulting strain, in which a PPTase gene was replaced with aac (3)IV, was confirmed by PCR analysis using primers accordingly. The disruption of FKPPT1, FKPPT2, FKPPT3 and FKPPT4 in S. tsukubaensis L19 were performed as described above, resulting in mutant strains sHJ0015-sHJ0018, respectively.

Construction of PPTase gene overexpression mutant strains

A site-specific integration vector pIJ866038, containing egfp, Ф31 int and attP, was used to construct an integration recombinant plasmid. The egfp was replaced with ermEp* promoter and a multiple cloning site. The NdeI/NotI DNA fragments of each PPTase gene were cloned from S. tsukubaensis L19 into the same sites of pIJ8660, resulting in plasmids pYY0099-pYY0102. Each of pYY0099-pYY0102 was transferred to S. tsukubaensis L19 via conjugal transfer from E. coli ET12567 (pUZ8002) using standard procedures. The resulting strains, in each of which a PPTase gene was expressed under the control of ermEp*, were designated as strains sHJ0019-sHJ0022 and confirmed by PCR analysis.

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Wang, Y.-Y. et al. Characterization of Discrete Phosphopantetheinyl Transferases in Streptomyces tsukubaensis L19 Unveils a Complicate Phosphopantetheinylation Network. Sci. Rep. 6, 24255; doi: 10.1038/srep24255 (2016).

References

Beld, J., Sonnenschein, E. C., Vickery, C. R., Noel, J. P. & Burkart, M. D. The phosphopantetheinyl transferases: catalysis of a post-translational modification crucial for life. Nat. Prod. Rep. 31, 61–108 (2014).

Sunbul, M., Zhang, K. & Yin, J. Chapter 10 using phosphopantetheinyl transferases for enzyme posttranslational activation, site specific protein labeling and identification of natural product biosynthetic gene clusters from bacterial genomes. Methods Enzymol. 458, 255–275 (2009).

Walsh, C. T., Gehring, A. M., Weinreb, P. H., Quadri, L. E. & Flugel, R. S. Post-translational modification of polyketide and nonribosomal peptide synthases. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 1, 309–315 (1997).

Huang, Y., Wendt-Pienkowski, E. & Shen, B. A dedicated phosphopantetheinyl transferase for the fredericamycin polyketide synthase from Streptomyces griseus. J. Biol. Chem. 281, 29660–29668 (2006).

Dall’aglio, P. et al. Analysis of Streptomyces coelicolor phosphopantetheinyl transferase, AcpS, reveals the basis for relaxed substrate specificity. Biochemistry 50, 5704–5717 (2011).

Chirgadze, N. Y., Briggs, S. L., McAllister, K. A., Fischl, A. S. & Zhao, G. Crystal structure of Streptococcus pneumoniae acyl carrier protein synthase: an essential enzyme in bacterial fatty acid biosynthesis. EMBO J. 19, 5281–5287 (2000).

Sanchez, C., Du, L., Edwards, D. J., Toney, M. D. & Shen, B. Cloning and characterization of a phosphopantetheinyl transferase from Streptomyces verticillus ATCC15003, the producer of the hybrid peptide-polyketide antitumor drug bleomycin. Chem. Biol. 8, 725–738 (2001).

Meiser, P. & Muller, R. Two functionally redundant Sfp-type 4′-phosphopantetheinyl transferases differentially activate biosynthetic pathways in Myxococcus xanthus. Chembiochem 9, 1549–1553 (2008).

Joshi, A. K., Zhang, L., Rangan, V. S. & Smith, S. Cloning, expression and characterization of a human 4′-phosphopantetheinyl transferase with broad substrate specificity. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 33142–33149 (2003).

Zhang, J. et al. A phosphopantetheinylating polyketide synthase producing a linear polyene to initiate enediyne antitumor antibiotic biosynthesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 105, 1460–1465 (2008).

Murugan, E. & Liang, Z. X. Evidence for a novel phosphopantetheinyl transferase domain in the polyketide synthase for enediyne biosynthesis. FEBS Lett. 582, 1097–1103 (2008).

Lu, Y. W., San Roman, A. K. & Gehring, A. M. Role of phosphopantetheinyl transferase genes in antibiotic production by Streptomyces coelicolor. J. Bacteriol. 190, 6903–6908 (2008).

Jiang, H. et al. Improvement of Natamycin Production by Engineering of Phosphopantetheinyl Transferases in Streptomyces chattanoogensis L10. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 79, 3346–3354 (2013).

Weissman, K. J., Hong, H., Oliynyk, M., Siskos, A. P. & Leadlay, P. F. Identification of a phosphopantetheinyl transferase for erythromycin biosynthesis in Saccharopolyspora erythraea. Chembiochem 5, 116–125 (2004).

Mootz, H. D., Finking, R. & Marahiel, M. A. 4′-phosphopantetheine transfer in primary and secondary metabolism of Bacillus subtilis. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 37289–37298 (2001).

Wang, Y. Y. et al. Characterization and Evolutionary Implications of the Triad Asp-Xxx-Glu in Group II Phosphopantetheinyl Transferases. Plos One 9, e103031 (2014).

Barekzi, N., Joshi, S., Irwin, S., Ontl, T. & Schweizer, H. P. Genetic characterization of pcpS, encoding the multifunctional phosphopantetheinyl transferase of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Microbiology 150, 795–803 (2004).

Copp, J. N., Roberts, A. A., Marahiel, M. A. & Neilan, B. A. Characterization of PPTNs, a cyanobacterial phosphopantetheinyl transferase from Nodularia spumigena NSOR10. J. Bacteriol. 189, 3133–3139 (2007).

Roberts, A. A., Copp, J. N., Marahiel, M. A. & Neilan, B. A. The Synechocystis sp. PCC6803 Sfp-type phosphopantetheinyl transferase does not possess characteristic broad-range activity. Chembiochem 10, 1869–1877 (2009).

Wang, Y. Y. et al. Two Bacterial Group II Phosphopantetheinyl Transferases Involved in Both Primary Metabolism and Secondary Metabolism. Curr. Microbiol. 70, 390–397 (2015).

Allison, A. C. Immunosuppressive drugs: the first 50 years and a glance forward. Immunopharmacology 47, 63–83 (2000).

Barreiro, C. & Martinez-Castro, M. Trends in the biosynthesis and production of the immunosuppressant tacrolimus (FK506). Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 98, 497–507 (2014).

Kino, T. et al. FK-506, a novel immunosuppressant isolated from a Streptomyces. I. Fermentation, isolation and physico-chemical and biological characteristics. J. Antibiot. (Tokyo) 40, 1249–1255 (1987).

Kino, T. et al. FK-506, a novel immunosuppressant isolated from a Streptomyces. II. Immunosuppressive effect of FK-506 in vitro. J. Antibiot. (Tokyo) 40, 1256–1265 (1987).

Goranovic, D. et al. Origin of the allyl group in FK506 biosynthesis. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 14292–14300 (2010).

Mo, S. et al. Biosynthesis of the allylmalonyl-CoA extender unit for the FK506 polyketide synthase proceeds through a dedicated polyketide synthase and facilitates the mutasynthesis of analogues. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 133, 976–985 (2011).

Wang, Y. Y. et al. Biochemical characterization of a malonyl-specific acyltransferase domain of FK506 biosynthetic polyketide synthase. Protein Pept. Lett. 22, 2–7 (2015).

Jiang, H. et al. An acyltransferase domain of FK506 polyketide synthase recognizing both an acyl carrier protein and coenzyme A as acyl donors to transfer allylmalonyl and ethylmalonyl units. FEBS J. 282, 2527–2539 (2015).

Bunet, R. et al. A single Sfp-type phosphopantetheinyl transferase plays a major role in the biosynthesis of PKS and NRPS derived metabolites in Streptomyces ambofaciens ATCC23877. PLoS One 9, e87607 (2014).

Kelemen, G. H. et al. Developmental regulation of transcription of whiE, a locus specifying the polyketide spore pigment in Streptomyces coelicolor A3(2). J. Bacteriol. 180, 2515–2521 (1998).

Novakova, R., Bistakova, J. & Kormanec, J. Characterization of the polyketide spore pigment cluster whiESa in Streptomyces aureofaciens CCM3239. Arch. Microbiol. 182, 388–395 (2004).

Yu, T. W. et al. Engineered Biosynthesis of Novel Polyketides from Streptomyces Spore Pigment Polyketide Synthases. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 120, 7749–7759 (1998).

Kieser, T., Bibb, M. J., Buttner, M. J., Chater, K. F. & Hopwood, D. A. Practical Streptomyces Genetics. (The John Innes Foundation, Norwich, United Kingdom; 2000).

Delcher, A. L., Harmon, D., Kasif, S., White, O. & Salzberg, S. L. Improved microbial gene identification with GLIMMER. Nucleic Acids Res. 27, 4636–4641 (1999).

Guo, F. B., Ou, H. Y. & Zhang, C. T. ZCURVE: a new system for recognizing protein-coding genes in bacterial and archaeal genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 31, 1780–1789 (2003).

Tatusov, R. L., Galperin, M. Y., Natale, D. A. & Koonin, E. V. The COG database: a tool for genome-scale analysis of protein functions and evolution. Nucleic Acids Res. 28, 33–36 (2000).

Gust, B., Challis, G. L., Fowler, K., Kieser, T. & Chater, K. F. PCR-targeted Streptomyces gene replacement identifies a protein domain needed for biosynthesis of the sesquiterpene soil odor geosmin. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 100, 1541–1546 (2003).

Sun, J., Kelemen, G. H., Fernandez-Abalos, J. M. & Bibb, M. J. Green fluorescent protein as a reporter for spatial and temporal gene expression in Streptomyces coelicolor A3(2). Microbiology 145 (Pt 9), 2221–2227 (1999).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by Grants LR16H300001 from Zhejiang Provincial Natural Science Foundation of China, 31200600 from National Natural Science Foundation of China and 2011BAD23B05-2 from National Key Technologies R & D Program of China. The nucleotide sequence(s) reported in this paper has been submitted to the GenBank with accession number(s) KT582112-KT582116.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

H.J. and Y.Q.L. designed experiments. H.J. and Y.Y.W. performed the experiments, analyzed the data and wrote the manuscript. X.S.Z., H.D.L. and N.N.R. produced ACPs. X.H.J. performed HPLC-MS.

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, YY., Zhang, XS., Luo, HD. et al. Characterization of Discrete Phosphopantetheinyl Transferases in Streptomyces tsukubaensis L19 Unveils a Complicate Phosphopantetheinylation Network. Sci Rep 6, 24255 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep24255

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/srep24255

This article is cited by

-

Microbial cell factories based on filamentous bacteria, yeasts, and fungi

Microbial Cell Factories (2023)

-

Enhancement of milbemycins production by phosphopantetheinyl transferase and regulatory pathway engineering in Streptomyces bingchenggensis

World Journal of Microbiology and Biotechnology (2023)

-

Activation and discovery of tsukubarubicin from Streptomyces tsukubaensis through overexpressing SARPs

Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology (2021)

-

Escherichia coli Nissle 1917 secondary metabolism: aryl polyene biosynthesis and phosphopantetheinyl transferase crosstalk

Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology (2021)

-

Conjugational delivery of chromosomal integrative constructs for gene expression in the carbendazim-degrading Rhodococcus erythropolis D-1

Annals of Microbiology (2018)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.